Abstract

Background

Spatial structure of plants in a population reflects complex interactions of ecological and evolutionary processes. For dioecious plants, differences in reproduction cost between sexes and sizes might affect their spatial distribution. Abiotic heterogeneity may also affect adaptation activities, and result in a unique spatial structure of the population. Thus, we examined sex- and size-related spatial distributions of old-growth forest of dioecious tree Torreya nucifera in extremely heterogeneous Gotjawal terrain of Jeju Island, South Korea.

Methods

We generated a database of location, sex, and size (DBH) of T. nucifera trees for each quadrat (160 × 300 m) in each of the three sites previously defined (quadrat A, B, C in Site I, II, and III, respectively). T. nucifera trees were categorized into eight groups based on sex (males vs. females), size (small vs. large trees), and sex by size (small vs. large males, and small vs. large females) for spatial point pattern analysis. Univariate and bivariate spatial analyses were conducted.

Results

Univariate spatial analysis showed that spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees differed among the three quadrats. In quadrat A, individual trees showed random distribution at all scales regardless of sex and size groups. When assessing univariate patterns for sex by size groups in quadrat B, small males and small females were distributed randomly at all scales whereas large males and large females were clumped. All groups in quadrat C were clustered at short distances but the pattern changed as distance was increased. Bivariate spatial analyses testing the association between sex and size groups showed that spatial segregation occurred only in quadrat C. Males and females were spatially independent at all scales. However, after controlling for size, males and females were spatially separated.

Conclusions

Diverse spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees across the three sites within the Torreya Forest imply that adaptive explanations are not sufficient for understanding spatial structure in this old-growth forest. If so, the role of Gotjawal terrain in terms of creating extremely diverse microhabitats and subsequently stochastic processes of survival and mortality of trees, both of which ultimately determine spatial patterns, needs to be further examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The spatial structure of plants in a population reflects complex interactions of ecological and evolutionary processes (Epperson 2005). Processes that can generate plant spatial patterns include intra- and interspecific interactions (Stoll and Bergius 2005; Nanami et al. 2011), environmental heterogeneity (Zuo et al. 2008), breeding systems (Bleher et al. 2002), and disturbances (Wolf 2005; Rayburn and Monaco 2011). By analyzing spatial patterns of individuals, it might be possible to identify physical conditions and competitive factors contributing to the spatial structure of a population (Bell et al. 1993; Law et al. 2009; Rayburn et al. 2011). For example, clumped pattern most frequently observed in natural populations has been interpreted as evidence of positive interactions among individuals (Callaway 1995), patch distributions of resources (Schenk et al. 2003; Perry et al. 2009), and seed dispersion by gravity (Bleher et al. 2002; Gao et al. 2009).

Previous studies on spatial patterns of plants have focused on hermaphrodite or monoecious species whose parent plants can produce seeds (Nanami et al. 1999; Rayburn et al. 2011; Benot et al. 2013; Cheng et al. 2014). On the other hand, studies on the influences of dioecy consisting of separate male and female plants on spatial structure of tree populations are relatively limited (Gibson and Menges 1994; Hultine et al. 2007; Garbarino et al. 2015). For dioecious plants, spatial distribution of mature males and females is crucial to population survival because they can only reproduce by outcrossing (Bawa 1980; Thomson and Barrett 1981; Osunkoya 1999). Furthermore, females tend to allocate a greater proportion of resources to sexual reproduction than to growth and maintenance compared to males (Lloyd and Webb 1977; Opler and Bawa 1978; Delph 1999; Obeso 2002). Differences in reproductive cost between sexes may result in differential fitness between sexes across environmental gradients. Such differences can subsequently generate spatial segregation of sexes (SSS) (Bierzychudek and Eckhart 1988; Nuñez et al. 2008). In other words, females with resource limitations due to high reproductive costs will occupy more favorable or less stressful conditions regarding elevation (Garbarino et al. 2015), water availability (Ortiz et al. 2002), and/or soil fertility (Lawton and Cothran 2000). For example, female Acer negundo (Dawson and Ehleringer 1993), Juniperus virginiana (Lawton and Cothran 2000), and Salix glauca (Dudley 2006) are found on sites with relatively greater amounts of moisture. However, conflicting results relevant to SSS have recently been documented in several plant species (Ueno et al. 2007, Schmidt 2008, Gao et al. 2009, Forero-Montaña et al. 2010; Garbarino et al. 2015).

Some studies on sex-related size (or age) structures of dioecious species have been published (Goto et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2010; Gabarino et al. 2015). Reproductive costs are age-specific and reproductive investment is variable during lifespan of plants (Silvertown and Dodd 1999; Montesinos et al. 2006). Nanami et al. (2005) have reported that dioecious individuals tend to shift from clumped distribution to random distribution as tree size increases due to density-dependent mortality caused by intraspecific competition. Therefore, interactions between sex and size in dioecious species should be considered in spatial structure study of dioecious population.

Torreya nucifera (Taxaceae) is a dioecious gymnosperm currently distributed in southern parts of South Korea and Japan. The largest (n = 2861) and oldest (mostly 200–400 years old, max. ~ 880 years old) population of T. nucifera in the world (Torreya Forest hereafter) is located in Jeju Island, South Korea. In a previous study by Kang and Shin (2012), the Torreya population in Jeju Island could be separated into three sites depending on sex ratio and DBH (diameter at breast height). Abiotic heterogeneity influences adaptation activities such as competition, growth, and mortality of individuals, resulting in a unique spatial structure of the population (Scarano 2002; Zuo et al. 2008; Perry et al. 2009). Gotjawal terrain where Torreya Forest exists is a unique volcanic area with lava blocks scattered extremely disorderly (Jeon et al. 2012). Thus, Gotjawal terrain with severe topographic heterogeneity generates highly diverse microclimate (Choi and Lee 2015). Furthermore, Gotjawal terrain represents poor soil development and oligotrophic and stressful environment to plants. Therefore, current spatial structure of Torreya Forest is likely to reflect the long history of its survival and mortality in such a harsh environment. However, the spatial structure of Torreya Forest has not been examined so far.

As plants are sessile, their survival is mostly determined at quite a local scale, even at a scale of a few centimeters, by both biotic and abiotic factors rather than by spatial average of its overall population (Stoll and Prati 2001; Benot et al. 2013). If so, dioecious sexual system of T. nucifera trees, size difference among their three sites, and complexity of the terrain should all be considered in the study of spatial structure of Torreya Forest in Jeju Island. In this study, the following aspects were examined: (1) the distribution pattern of T. nucifera trees according to sex and size at each site, (2) the site differences in those distribution patterns, and (3) the pattern of spatial segregation of sexes and sizes at each site.

Methods

Study species and site

Torreya nucifera (Taxaceae) is a dioecious evergreen gymnosperm that can grow up to 25 m in height. Its pollination occurs in April and green fleshy aril-covered seeds mature in the fall one year after pollination. Various parts of this tree have traditionally been used. For example, its wood has been used for furniture and its seeds have been used for anthelmintic and oriental medicines and oil.

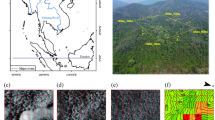

Torreya Forest (Natural Monument No. 374 in South Korea) is located in Jeju Island (33° 29′ N, 126° 48′ E) (Fig. 1a). This forest (44.8 ha in area, 143 m mean a.s.l.) extends 1.4 km in the north-south direction with a width of 0.6 km. It is located between two small volcanoes: Darangshioreum (382.4 m a.s.l.) and Dotoreum (a volcano near the southern end of the population; 284.2 m a.s.l.). In 1999, all T. nucifera trees with DBH ≥ 6 cm were tagged and tending was started for 11 plots along trails within the forest (Fig. 1b). Torreya Forest terrain is defined as Gujwa-Seongsan Gotjawal, a transition lava zone distributing both pahoehoe and aa lava flows (Jeon et al. 2012). Although T. nucifera is a domonant species in this forest, the Forest consists of diverse evergreen trees with a total of 276 plant taxa, including Mallotus japonicus, Machilus thunbergii, Orixa japonica, and Polystichum tripteron [Korea Tree Health Association (KTHA) 1999; Lee 2009; Shin et al. 2010; Choi and Lee 2015]. Figure 2 demonstrates characteristic features of wild Torreya Forest. According to 2007–2016 data from Gujwa Regional Meteorological Office close to the Torreya Forest, the mean monthly temperature ranges from 5.3 °C in January to 26.7 °C in August (mean annual temperature, 15.7 °C). Its mean annual precipitation is 1774.2 mm with a peak in August (307.8 mm) with mean annual wind speed of 4.0 m/s (Korea Meteorological Administration 2017).

a Location of Torreya Forest in Jeju Island, South Korea. b The 11 plots divided by trails (Lee 2009) were categorized into three sites depending on the sex ratio and DBH gradient by Kang and Shin (2012): Site I in the southern part of the forest including plots 3–5, Site II in the middle part including plots 2–7, and Site III in the northern part including plots 1, 8, 9, and 10

Data collection

The planimetric map was transformed into an image file through high-resolution scanning using a survey map of the location of T. nucifera trees (KTHA 1999). Warping was performed by assigning coordinates to each edge. Digitizing process was then used to obtain coordinates for 2861 individuals (1498 males and 1363 females). By inputting attribute values such as sex, DBH, and sites for each individual, a database of location and ecological traits of T. nucifera trees was completed. Sex and DBH data were obtained from KTHA (1999) and Lee (2009). Torreya Forest exhibited a gradient of sex ratio and DBH from the southern end to the northern end of the forest. In this study, we analyzed spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees based on the three sites defined by Kang and Shin (2012). Numbers, sex ratio, and DBH of T. nucifera trees in the three sites are shown in Table 1. ArcGIS Ver. 9.3. (ESRI 2008) was used for all analyses described above.

In Torreya Forest, there are somewhat unnatural spaces where T. nucifera trees are absent or scant due to the planting of Pinus thunbergii trees and various herbaceous plants, paved entrance, and trails. Therefore, a quadrat (160 × 300 m) was established in each of the three sites to represent the typical local condition (Fig. 3a): quadrat A for Site I, quadrat B for Site II, and quadrat C for Site III. The distribution of T. nucifera trees according to sex and size (DBH) in each quadrat is shown in Fig. 3b.

Data analyses

T. nucifera trees were categorized into eight groups based on sex (males and females), size (small trees, DBH < 50 cm; and large trees, DBH ≥ 50 cm), and sex by size (small males, large males, small females and large females) for spatial point pattern analysis.

O-ring statistics O(r) was employed to describe the average density of points at a distance of r (Wiegand and Moloney 2004; Law et al. 2009). Value of O(r) was calculated as follows. Around each individual data point, numerous circles with radius r were drawn and the correlation between the average number of individuals within numerous circles and radius r was deduced to determine the O value. O-ring statistics included univariate and bivariate analyses (Zhang et al. 2010). Univariate statistical analysis of O11(r) was used to analyze spatial patterns between individuals in a group while bivariate statistical analysis of O12(r) was used to analyze spatial relationships between two different groups. O11(r) was applied to assess spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees within two sexes and/or two size groups (e.g., male, female, small, and large) in Torreya Forest. O12(r) was used to determine whether there was a spatial relationship between the two sexes and/or the two size groups (e.g., males vs. females and small vs. large trees). To conduct significance test for O(r) value at each distance r, null hypothesis was formed using complete spatial randomness (CSR). Then 95% confidence intervals for both univariate and bivariate analyses were computed from 999 Monte Carlo simulations. If O(r) value was above the CSR value, individuals were considered to be clumped. It O(r) value was within 95% confidence intervals, individuals were considered to be randomly distributed. If it was below the CSR value, individuals were considered to be regularly distributed. All calculations and simulations were performed using PROGRAMITA software (Wiegand and Moloney 2004).

Results

Ecological characteristics of the three sites

Ecological characteristics such as sex ratio, size, and density of T. nucifera trees in each quadrat are shown in Table 2. T. nucifera trees of quadrat A (at Site I) were male-biased (sex ratio = 0.62). Large trees were about four times more abundant than small trees (n = 241 vs. 62). The mean DBH was relatively large whereas its average density was the lowest among the three quadrats. On the other hand, T. nucifera trees in quadrat B (at Site II) and C (at Site III) showed a 1:1 sex ratio and somewhat higher density than quadrat A. In addition, in quadrat C, T. nucifera trees had the smallest mean DBH, and small trees were more abundant than large trees (n = 230 vs. 177).

Univariate spatial analyses

Univariate analyses showed that spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees differed between groups (e.g., male vs. female, small vs. large) of each quadrat (Figs. 4, 5 and 6. In quadrat A, all trees and eight groups of T. nucifera showed random distribution at all scales (Fig. 4). In quadrat B, all trees demonstrated random distribution at all scales. However, when sex and size were considered, spatial pattern changed. Males were randomly distributed at all scales while females were weakly clumped at 0–17 m (except for 8–10 m). Small trees were randomly distributed at all scales while large trees were clumped (2–23 m) or regularly (54–58 m) distributed at some distances. By assessing univariate patterns of four groups of sex by size, small males and small females were distributed randomly at all scales. However, large males and large females were clumped at 0–16 m scales. Finally, all groups in quadrat C were clumped at short distances. They were distributed randomly or regularly as the distance was increased. When sex and size were combined, males (0–32 m) clumped more strongly than females (0–12 m) in the small tree group whereas females (0–24 m) clumped more strongly than males (0–17 m) in the large tree group. Thus, spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees varied among three quadrats. For example, large females had different distribution types for each quadrat that are random (0–60 m) in quadrat A, clumped (5–16 m) in quadrat B, and regular (48–60 m) in quadrat C (Figs. 4, 5 and 6).

Spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees in univariate analyses in quadrat A. Analyses were conducted for all trees pooled over sex and size groups, separately for each sex and size groups, and then for combination groups of sex and size (e.g., small males, large males, small females, and large females). Solid lines indicate O11(r) value from each analysis; dashed lines indicate 95% confidence envelopes regarding the random spatial structure null hypothesis

Spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees in univariate analyses in quadrat B. Analyses were conducted for all trees pooled over sex and size groups, separately for each sex and size groups, and then for combination groups of sex and size (e.g., small males, large males, small females, and large females). Solid lines indicate O11(r) value from each analysis; dashed lines indicate 95% confidence envelopes regarding the random spatial structure null hypothesis

Spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees in univariate analyses in quadrat C. Analyses were conducted for all trees pooled over sex and size groups, separately for each sex and size groups, and then for combination groups of sex and size (e.g., small males, large males, small females, and large females). Solid lines indicate O11(r) value from each analysis; dashed lines indicate 95% confidence envelopes regarding the random spatial structure null hypothesis

Bivariate spatial analyses

Bivariate analyses for spatial associations between sexes and/or size groups showed that spatial segregation occurred only in quadrat C (Fig. 7). Males and females were spatially independent at all scales. Significant spatial segregation was observed between small and large trees (4–22 m). When combination groups of sex and size were examined, repulsion between groups was notable: small males vs. small females at 50–60 m scales; large males vs. small females at 12–17 m scales; small males vs. large females at 0–22 m scales; and large males vs. large females at 37–60 m scales.

Spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees in bivariate analyses in quadrat C. Analyses were conducted for all trees pooled over sex and size groups, separately for each sex and size groups, and then for combination groups of sex and size (e.g., small males, large males, small females, and large females). Solid lines indicate O12(r) value from each analysis; dashed lines indicate 95% confidence envelopes regarding the random spatial structure null hypothesis

Discussion

Spatial patterns of individual T. nucifera trees within and among sites

This is the first study to reveal the spatial pattern of old trees that have survived for several hundreds of years in almost natural conditions in Korea. Individual trees of T. nucifera in Torreya Forest were distributed randomly, clumped, or regularly with each other depending on the sites examined.

Site I at the southern end of Torreya Forest, adjacent to a small volcano called Dotoreum (284.2 m a.s.l.), is characterized by relatively large proportion of oldaged trees. Many studies on dioecious species have reported that there is a difference in distribution pattern of individuals according to sex (Zhang et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2014; Garbarino et al. 2015). However, both male and female trees of T. nucifera were randomly distributed in quadrat A, not supporting sex-specific segregation between male and female trees. Random distribution of both sexes has also been reported in the old-growth plot of Acer barbinerve (Pan et al. 2010). Several studies in recent years have also emphasized the effects of both biotic and abiotic conditions on plant spatial patterns. For example, old trees tend to be randomly distributed as a result of stochastic mortality and intra- or interspecific competition for resources (Nanami et al. 2005). Dying seedlings under large trees are frequently found in Torreya Forest. Even if seedlings were initially clumped around female trees, only small gaps randomly scattered in Gotjawal terrain may allow seedlings to survive and finally can generate a random dispersion pattern.

Site II, corresponding to the middle area of the forest, showed intermediate values in sex ratio and size between Site I and Site III (Kang and Shin 2012). It has been reported that as the size of plant is increased, the clumped pattern is generally weakened (Wang et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2014). Recently, Garbarino et al. (2015) showed that large males and females of Taxus baccata, which is phylogenetically related to T. nucifera, were randomly distributed while small trees were mostly clumped. However, in quadrat B, regardless of sexes, small trees of both sexes were randomly distributed while large male and female trees were clumped at 0–16 m scales (Fig. 5). The clumped patterns of large trees are in contrast to the results as mentioned above. However, several authors suggest that the increase in the clumped pattern with age might be attributable to interspecific competition (Nanami et al. 2011), differential mortality of juveniles (Briggs and Gibson 1992), and clonal structure (Peterson and Squiers 1995). This forest is mixed with diverse broad-leaved plants and P. thunbergii. Lee (2005) recognized that interspecific competition greatly reduced the vigor of T. nucifera trees. The fact that the vigor of trees, especially female trees, was significantly improved after removal of epiphytes from the canopy of T. nucifera trees (Kang and Shin 2012) also supports the importance of interspecific competition. The influence of competition on the clumping of large trees in Site II remains to be tested because we did not examine the density or distance between neighboring trees in this site.

Site III in the northern part of the forest is characterized by relatively small trees and more females than males than in other sites (Kang and Shin 2012). Individual trees in quadrat C were clustered at short distances and distributed randomly or regularly as distance increased (Fig. 6). Even when combining sex and size, males (0–32 m) clumped more strongly than females (0–12 m) in small trees but females (0–24 m) clumped more strongly than males (0–17 m) in large trees. In other words, consistent spatial patterns across sex and size groups do not exist at all in this site. A simple adaptive explanation for such complex patterns may not be possible at this stage.

In this forest, anthropogenic activities have been controlled for several hundreds of years (Kim 1985, Shin et al. 2010). However, we speculate that Site III might have been sporadically subjected to severe disturbances by human activities such as logging. This is particularly likely because this site (Site III) is located near the entrance to the forest which is very easy to access compared to Site I near a small volcano. The most convincing evidence for artificial planting in this site comes from aerial photos taken from 1967 to 2015 (Fig. 8). In 1967, it appeared that certain locations at Site III were largely free of vegetation. Since then, its vegetation coverage has increased significantly until 2015. Such drastic changes in vegetation coverage at those locations are not expected to occur by natural regeneration because it takes about 54 years for the DBH of T. nucifera to grow up to 6 cm DBH (Lee 2005). Thus, those photos are highly likely to reflect that artificial planting occurred intensively around 1970s when the Korean government pushed a strong reforestation policy on a nationwide scale. Kang and Shin (2012) provided another piece of evidence for artificial planting in this site. In their study, some plots at Site III are deviated quite a bit from the site’s sex ratio and mean size. For example, plot 10 (Fig. 1b) which was almost a vacant area in the aerial photo (Fig. 8a) consists of smaller trees than other plots and its density (114.7 trees/ha) being twice as high as the average population density of 67.6 trees/ha. If T. nucifera trees were planted during the 1970s, planting would be concentrated in less rocky localities covered with some soils, perhaps being responsible for clumped spatial patterns at a fine scale as detected in this study. Unfortunately, written documents regarding the reforestation of T. nucifera trees are not available to confirm this inference.

Aerial photos of Torreya Forest in Jeju island in 1967 (a), 1990 (b), 2003 (c), and 2015 (d). (National Geographic Information Institute of Korea 2016). White dotted box in a represents plots at Site III with thin or scant canopy cover in 1967

Spatial segregation of sexes in T. nucifera

The SSS expected under the hypothesis of high reproductive cost of females has been reported in > 30 species from 24 families of seed plants (Barrett and Hough 2013). In this study, SSS occurred only in Site III, e.g., between small males vs. small females (50–60 m scales), large males vs. small females (12–17 m scales), small males vs. large females (0–22 m scales), and large males vs. large females (37–60 m scales) (Fig. 7). SSS detected only in the site with small trees with the highest density is analogous with the case of Fraxinus mandshurica. In dioecious F. mandshurica, spatial segregation between sexes was found in the secondary forests, but not in the old-growth (Zhang et al. 2010). They ascribed a lack of SSS in old-growth forest of F. mandshurica to sex-specific responses to microenvironments. In this study, Site I trees which were larger than ones in other sites were randomly distributed regardless of sex and size groups. Currently, it is unknown whether Site I trees exhibit sex-differential responses to microenvironments.

Influence of the rocky Gotjawal terrain

Diverse spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees across the three sites may imply both biotic and abiotic effects in this forest. Most of all, the role of Gotjawal terrain in terms of creating extremely diverse microhabitats, and subsequently, stochastic processes of survival or mortality of trees need to be emphasized. In stressful habitats such as the rocky coasts and alpine forests, spatial structure largely depends on constraining factors such as topography and disturbances (Camarero et al. 2000; Scarano 2002; Humphries et al. 2008). If so, we can draw a couple of inferences regarding the ecological role of Gotjawal terrain. Firstly, it seems that Gotjawal terrain is a major component affecting the distribution pattern of trees. In highly diverse microhabitats at small scales created in Gotjawal terrain, it may be difficult to expect a formation of resource gradient such as moisture or soil nutrients. That means, SSS would be difficult to expect. Furthermore, rocks and thin soils in Gotjawal terrain may cause stochastic processes over the survival and mortality, and consequently affecting spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees. Secondly, T. nucifera trees may have to respond to multiple stressors in circumstances with scattered lava blocks and little soil. Thus, diverse spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees may be an outcome of biotic as well as abiotic interactions that have occurred for hundreds of years.

Despite that this forest has been known to be a natural forest for such a long time, we found a new evidence for artificial interference in some plots especially near the entrance area. The rocky topography of Gotjawal terrain is certainly a component that has protected the historical and valuable T. nucifera trees in Jeju Island. Understanding of the spatial patterns of T. nucifera trees will help provide indispensable information on the interactions between trees on a stressful Gotjawal terrain. In order to figure out the biotic and abiotic factors affecting spatial patterns, it is also necessary to understand the tending and planting history in this forest.

Conclusions

Individual trees of dioecious T. nucifera were randomly distributed in an old-growth forest with over several hundreds of years of history. However, when the spatial relationship was assessed for sex and size groups, spatial patterns of trees tended to differ among the three sites within the forest, and spatial segregation was notable only in one site of which density was the highest among the three sites and artificial planting occurred several decades ago. Considering the extremely heterogeneous topography and thin soils of Gotjawal terrain, it may not be possible to expect SSS shown in many other dioecious species. We did not directly examine the topographic features and its ecological effects in this study. Incorporation of topological traits in Torreya Forest in spatial pattern analyses would be rewarding to identify biotic and abiotic effects affecting plant spatial distribution.

Abbreviations

- DBH:

-

Diameter at breast height

- KTHA:

-

Korea Tree Health Association

- SSS:

-

Spatial segregation of sexes

References

Barrett, S. C. H., & Hough, J. (2013). Sexual dimorphism in flowering plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 64, 67–82.

Bawa, K. S. (1980). Evolution of dioecy in flowering plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 11, 15–39.

Bell, G., Lechowicz, M. J., Appenzeller, A., Chandler, M., DeBlois, E., Jackson, L., Mackenzie, B., Preziosi, R., Schallenberg, M., & Tinker, N. (1993). The spatial structure of the physical environment. Oecologia, 96, 114–121.

Benot, M.-L., Bittebiere, A.-K., Ernoult, A., Clément, B., & Mony, C. (2013). Fine-scale spatial patterns in grassland communities depend on species clonal dispersal ability and interactions with neighbours. Journal of Ecology, 101, 626–636.

Bierzychudek, P., & Eckhart, V. (1988). Spatial segregation of the sexes of dioecious plants. The American Naturalist, 132, 34–43.

Bleher, B., Oberrath, R., & Böhning-Gaese, K. (2002). Seed dispersal, breeding system, tree density and the spatial pattern of trees–a simulation approach. Basic Applied Ecology, 3, 115–123.

Briggs, J. M., & Gibson, D. J. (1992). Effect of fire on tree spatial patterns in a tallgrass prairie landscape. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 119, 300–307.

Callaway, R. M. (1995). Positive interactions among plants. The Botanical Review, 61, 306–349.

Camarero, J. J., Gutiérrez, E., & Fortin, M-J. (2000). Spatial pattern of subalpine forest-alpine grassland ecotones in the Spanish Central Pyrenees. Forest Ecology and Management, 134, 1–16.

Cheng, X., Han, H., Kang, F., Song, Y., & Liu, K. (2014). Point pattern analysis of different life stage of Quercus liaotungensis in Lingkong Mountain, Shanxi Province, China. Journal of Plant Interactions, 9, 233–240.

Choi, B-K., & Lee, C-B. (2015). A study on the synecological values of the Torreya nucifera Forest (Natural Monument No. 374) at Pyeongdae-ri in Jeju Island. Journal of the Korean Institute of Traditional Landscape Architecture, 33, 87–98 (in Korean with English abstract).

Dawson, T. E., & Ehleringer, J. R. (1993). Gender-specific physiology, carbon isotope discrimination, and habitat distribution in boxelder, Acer negundo. Ecology, 74, 798–815.

Delph, L. F. (1999). Sexual dimorphism in life history. In M. A. Geber, T. E. Dawson, & L. F. Delph (Eds.), Gender and sexual dimorphism in flowering plants (pp. 149–173). Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Dudley, L. S. (2006). Ecological correlates of secondary sexual dimorphism in Salix glauca (Salicaceae). American Journal of Botany, 93, 1775–1786.

Environmental Systems Research Institute: ESRI. Arc/Info User’s Guide. Ver. 9.3. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA, USA; 2008.

Epperson, B. K. (2005). Estimating dispersal from short distance spatial autocorrelation. Heredity, 95, 7–15.

Forero-Montaña, J., Zimmerman, J. K., & Thompson, J. (2010). Population structure, growth rates and spatial distribution of two dioecious tree species in a wet forest in Puerto Rico. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 26, 433–443.

Garbarino, M., Weisberg, P. J., Bagnara, L., & Urbinati, C. (2015). Sex-related spatial segregation along environmental gradients in the dioecious conifer, Taxus baccata. Forest Ecology and Management, 358, 122–129.

Gao, P., Kang, M., Wang, J., Ye, Q., & Huang, H. (2009). Neither biased sex ratio nor spatial segregation of the sexes in the subtropical dioecious tree Eurycorymbus cavaleriei (Sapindaceae). Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 51, 604–613.

Gibson, D. J., & Menges, E. S. (1994). Population structure and spatial pattern in the dioecious shrub Ceratiola ericoides. Journal of Vegetation Science, 5, 337–346.

Goto, S., Shimatani, K., Yoshimaru, H., & Takahashi, Y. (2006). Fat-tailed gene flow in the dioecious canopy tree species, Fraxinus mandshurica var. japonica revealed by microsatellites. Molecular Ecology, 5, 2985–2996.

Hultine, K. R., Bush, S. E., West, A. G., & Ehleringer, J. R. (2007). Population structure, physiology and ecohydrological impacts of dioecious riparian tree species of western North America. Oecologia, 54, 85–93.

Humphries, H. C., Bourgeron, P. S., & Mujica-Crapanzano, L. R. (2008). Tree spatial patterns and environmental relationships in the forest-alpine tundra ecotone at Niwot Ridge, Colorado, USA. Ecological Research, 23, 589–605.

Jeon, Y., Ahn, U. S., Ryu, C. G., Kang, S. S., & Song, S. T. (2012). A review of geological characteristics of Gotjawal terrain in Jeju Island: preliminary study. The Geological Society of Korea, 48, 425–434 (in Korean with English abstract).

Kang, H., & Shin, S. (2012). Sex ratios and spatial structure of the dioecious tree Torreya nucifera in Jeju Island, Korea. Journal of Ecology and Field Biology, 35, 111–122.

Kim, Y. S. (1985). Phytogeographic distribution of genus Torreya of the world. Journal of Resource development, 4, 143–150.

Korea Meteorological Administration. Research for Climate Information. 2017. https://data.kma.go.kr/data/grnd/selectAwsList.do?pgmNo=35. Accessed on Aug. 2017.

Korea Tree Health Association: KTHA. Torreya nucifera Forest in Gujwa-eup: conservation and maintenance measures. Bukjeju-gun, Jeju; 1999. (in Korean).

Law, R., Illian, J., Burslem, D. F. R. P., Gratzer, G., Gunatilleke, C. V. S., & Gunatilleke, I. A. U. N. (2009). Ecological information from spatial patterns of plants: insights from point process theory. Journal of Ecology, 97, 616–628.

Lawton, R. O., & Cothran, P. (2000). Factors influencing reproductive activity of Juniperus virginiana in the Tennessee Valley. Journal of Torrey Botanical Society, 127, 271–279.

Lee, S. G. (2005). Genetic conservation strategy in the natural population of Torreya nucifera in Kujwa-eup. Cheju: Korea. MS Thesis. Sangji University, Wonju, Korea (in Korean with English abstract).

Lee, S. G. (2009). Studies on the biota, growth characteristics, and vegetational changes in relation to tending care intensity and conservation measures of the Torreya nucifera Forest in Gujwa-eup. Jeju: Korea. Ph.D. Dissertation. Sangji University, Wonju, Korea (in Korean with English abstract).

Lloyd, D. G., & Webb, C. J. (1977). Secondary sex characters in plants. The Botanical Review, 43, 177–216.

Montesinos, D., Luís, M. D., Verdú, M., Raventós, J., & García-Fayos, P. (2006). When, how and how much: gender-specific resource-use strategies in the dioecious tree Juniperus thurifera. Annals of Botany, 98, 885–889.

Nanami, S., Kawaguchi, H., & Yamakura, T. (1999). Dioey-induced spatial patterns of two codominant tree species, Podocarpus nagi and Neolitsea aciculate. Journal of Ecology, 87, 678–687.

Nanami, S., Kawaguchi, H., & Yamakura, T. (2005). Sex ratio and gender-dependent neighboring effects in Podocarpus nagi, a dioecious tree. Plant Ecology, 177, 209–222.

Nanami, S., Kawaguchi, H., & Yamakura, T. (2011). Spatial pattern formation and relative importance of intra- and interspecific competition in codominant tree species, Podocarpus nagi and Neolitsea aciculata. Eological Research, 26, 37–46.

National Geographic Information Institute of Korea. 2016. http://map.ngii.go.kr/ms/map/NlipMap.do. Accessed on Apr 2016.

Nuñez, C. I., Nuñez, M. A., & Kitzberger, T. (2008). Sex-related spatial segregation and growth in a dioecious conifer along environmental gradients in northwestern Patagonia. Ecoscience, 15, 73–80.

Obeso, J. R. (2002). The costs of reproduction in plants. New Phytologist, 155, 321–348.

Opler, P. A., & Bawa, K. S. (1978). Sex ratios in some tropical forest trees. Evolution, 32, 812–521.

Ortiz, P. L., Arista, M., & Talavera, S. (2002). Sex ratio and reproductive effort in the dioecious Juniperus communis subsp. alpina (Suter) Čelak. (Cupressaceae) along an altitudinal gradient. Annals of Botany, 89, 205–211.

Osunkoya, O. O. (1999). Population structure and breeding biology in relation to conservation in the dioecious Gardenia actinocarpa (Rubiaceae) - a rare shrub of North Queensland rainforest. Biological Conservation, 88, 347–359.

Pan, C., Zhang, C., Zhao, X., Xia, F., Zhou, H., & Wang, Y. (2010). Sex ratio and spatial patterns of males and females of different ages in the dioecious understory tree, Acer barbinerve, in a broad-leaved Korean pine forest. Biodiversity Science, 18, 292–299 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Perry, G. L. W., Enright, N. J., Miller, B. P., & Lamont, B. B. (2009). Nearest-neighbour interactions in species-rich shrublands: the roles of abundance, spatial patterns and resources. Oikos, 118, 161–174.

Peterson, C. J., & Squiers, E. R. (1995). Competition and succession in an aspen-white-pine forest. Journal of Ecology, 83, 449–457.

Rayburn, A. P., & Monaco, T. A. (2011). Linking plant spatial patterns and ecological processes in grazed Great Basin plant communities. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 64, 276–282.

Rayburn, A. P., Schiffers, K., & Schupp, E. W. (2011). Use of precise spatial data for describing spatial patterns and plant interactions in a diverse Great Basin shrub community. Plant Ecology, 212, 585–594.

Scarano, F. R. (2002). Structure, function and floristic relationships of plant communities in stressful habitats marginal to the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest. Annals of Botany, 90, 517–524.

Schenk, H. J., Holzapfel, C., Hamilton, J. G., & Mahall, B. E (2003). Spatial ecology of a smalldesert shrub on adjacent geological substrates. Journal of Ecology, 91, 383–395.

Schmidt, J. P. (2008). Sex ratio and spatial pattern of males and females in the dioecious sandhill shrub, Ceratiola ericoides ericoides (Empetraceae) Michx. Plant Ecology, 196, 281–288.

Shin, H., Lee, K., Park, N., & Jung, S. Y. (2010). Vegetation structure of the Torreya nucifera stand in Korea. Journal of Korean Forest Society, 99, 312–322 (in Korean with English abstract).

Silvertown, J., & Dodd, M. (1999). The demographic cost of reproduction and its consequences in balsam fir (Abies balsamea). The American Naturalist, 154, 321–332.

Stoll, P., & Bergiou, E. (2005). Pattern and process: competition causes regularspacing of individuals within plant populations. Journal of Ecology, 93, 395–403.

Stoll, P., & Prati, D. (2001). Intraspecific aggregation alters competitive interactions in experimental plant communities. Ecology, 82, 319–327.

Thomson, J. D., & Barrett, S. C. H. (1981). Selection for outcrossing, sexual selection, and the evolution of dioecy in plants. The American Naturalist, 118, 443–449.

Ueno, N., Suyama, Y., & Seiwa, K. (2007). What makes the sex ratio female-biased in the dioecious tree Salix sachalinensis? Journal of Ecology, 95, 951–959.

Wang, X., Ye, J., Li, B., Zhang, J., Lin, F., & Hao, Z. (2010). Spatial distributions of species in an old-growth temperature forest, northestern China. Canada Journal of Forest Research, 40, 1011–1019.

Wiegand, T., & Moloney, K. A. (2004). Rings, circles, and null-models for point pattern analysis in ecology. Oikos, 104, 209–229.

Wolf, A. (2005). Fifty year record of change in tree spatial patterns within a mixed deciduous forest. Forest Ecology and Management, 215, 212–223.

Zhang, C., Zhao, X., Gao, L., & von Gadow, K. (2010). Gender-related distributions of Fraxinus mandshurica in secondary and old-growth forests. Acta Oecologica, 36, 55–62.

Zuo, X., Zhao, H., Zhao, X., Zhang, T., Guo, Y., Wang, S., & Drake, S. (2008). Spatial pattern and heterogeneity of soil properties in sand dunes under grazing and restoration in Horqin Sandy Land, Northern China. Soil & Tillage Research, 99, 202–212.

Acknowledgements

We thank anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments to the drafts of this article.

Funding

This study was supported by the Sungshin University Research Grant to HK (Grant no. 2015-1-11-051/1).

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conducted a survey together during the study period. SS analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. SL conducted the fieldwork. HK conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, S., Lee, S.G. & Kang, H. Spatial distribution patterns of old-growth forest of dioecious tree Torreya nucifera in rocky Gotjawal terrain of Jeju Island, South Korea. j ecology environ 41, 31 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-017-0050-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-017-0050-3