Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess retrospectively treatment and outcome of CML-patients in community based oncology practices in Germany and whether European LeukemiaNET (ELN) recommendations were followed.

Method

All Ph+, BCR-ABL1+ CML-patients who were treated between 11/2001 and 12/2015 in nine oncology group practices were analyzed retrospectively.

Results

Two hundred sixty patients with a median age of 60 (18–90) were analyzed. 254 (98%) were in chronic phase, 5 (2%) in accelerated and 1 (0.4%) in blast crisis. 248 patients (95%) received some form of TKI-therapy. 1st line TKI was imatinib in 197 patients (79%), 51 (21%) received a second generation TKI. 75% of TKI-therapies were monitored by PCR. Overall survival after 10 years according to Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was: CCI 2: 100%; CCI 3–4: 83%; CCI 5–6: 52%; CCI ≥7: 39%. More patients died from comorbidities (8%) than from CML (5%). Whether patients died was strongly correlated to CCI at diagnosis: CCI 2: 3% of patients died, CCI 3–4: 16% of patients died, CCI 5–6: 38% of patients died, CCI ≥ 7: 42% of patients died.

Conclusion

CML-patients treated in oncology group practices receive standard of care as recommended by ELN. Overall survival in routine care is comparable to international studies. Molecular monitoring should be improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Major progress has been made in CML-therapy since the introduction of imatinib, the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) which targets P210, the pathogenetic overexpressed BCR-ABL1-tyrosine kinase in CML [1,2,3]. Imatinib was the first TKI which received market approval in the European Union for the treatment of patients with CML in November 2001. Since then nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib and ponatinib have been approved for CML-treatment in first and further lines [4,5,6,7]. The European LeukemiaNET has published recommendations how newly diagnosed CML-patients should be treated and observed in chronic phase, accelerated phase and in blast crisis [8,9,10].

In Germany CML usually is diagnosed early in chronic phase due to frequent routine blood count analyses by general practitioners who send their patients to hematologists for further diagnostic procedures. During the last 25 years more than 600 experienced hematologists have left hematology departments and founded their own hematology-oncology-practices in the community. Most of them are group practices with the aim of caring for cancer patients close to their place of living [11]. Due to a close cooperation between oncology group practices and Comprehensive Cancer Centers a considerable percentage of CML-patients cared for in community-based oncology practices are treated within prospective German CML-trials [12]. Allogeneic transplants are performed in expert centers often within study protocols. Nevertheless the majority of CML-patients are not treated within study protocols for a variety of reasons (inclusion and exclusion criteria, severe comorbidities, low performance status, comedications, patient refusal etc.). Therefore it was of interest for us to compare the treatment and outcome of patients who received routine care with patients who were treated within prospective randomized trials and whether progress made in studies does translate into routine care management of CML-patients. The focus of this retrospective study was to find out how patients with CML are diagnosed and treated in hematology-oncology-group practices in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate which has 4 million inhabitants. With this project we wanted to answer the following questions:

-

1.

Are the European LeukemiaNET recommendations followed?

-

2.

What is the outcome of CML-patients with regards to overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) in routine care?

-

3.

What are the causes of death (CML versus comorbidities)?

Methods

All 20 hematology-oncology-practices in Rhineland-Palatinate were asked to contribute to the project. In the participating sites all patients who had been treated between 11/2001 and 12/2015 with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive- and/or BCR-ABL1-positive CML were documented retrospectively in a central data base and analyzed statistically using SPSS 19. All patients gave written informed consent for data documentation, collection, analysis and publication at the time of CML-diagnosis.

The following data were captured at diagnosis: age, sex, date of diagnosis, method of diagnosis (cytogenetics, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), polymerase chain reaction to detect BCR-ABL1 (PCR)), source of material (bone marrow versus peripheral blood), phase of disease (chronic phase, accelerated phase, blast crisis), EUTOS score [13]. Comorbidities at diagnosis were captured and classified using the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [14, 15]. Groups of patients were formed whether they had an index of 2, 3–4, 5–6 or ≥ 7.

Parameter during therapy: type of therapy (chemotherapy (hydroxyurea, busulfan, Ara-C), interferon, TKI (imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, ponatinib), combinations of chemotherapy, interferon and TKI, allogeneic transplantation), duration of therapy, lines of therapy, defined as every change in therapy regimen, progression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, method of response assessment during therapy (cytogenetics, FISH, PCR for BCR-ABL1), response to therapy according to European LeukemiaNET recommendations [8,9,10] after 12 months and in general (complete hematological response (CHR), complete cytogenetic response (CCyR), partial cytogenetic response (PCyR), no cytogenetic response (NCyR), major molecular response, defined as MR 3.0 or MR 4.0 (MMR), complete molecular response, defined as MR 4.5 or lower (CMR)) [8,9,10], death, causes of death (CML versus comorbidities).

At the end of the observation period the following were evaluated: overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), defined as below:

-

OS: survival from diagnosis to death or last contact

-

PFS: survival free from progression to accelerated phase (AP) or blastic phase (BP) or death or last contact

OS and PFS were analyzed for all documented patients as well as for a subgroup that was built according to the German CML IV trial [16]. Patients in this subgroup were diagnosed in chronic phase in November 2001 or later and received a TKI as 1st line treatment.

Statistical analyses were descriptive, specific hypotheses were not tested. Frequencies and statistical measures of central tendency were calculated and a regression analysis was conducted concerning response to TKI therapies. OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. OS and PFS were compared with the help of the two-sided log-rank test at a 5% significance level.

Results

Practices and patients

Of the 20 practices which were initially contacted nine practices consisting of 26 hematologists finally documented all their patients with the diagnosis of Philadelphia-chromosome-positive- or BCR-ABL1-positive CML. Overall 260 patients were documented with a median age of 60 (18–90). 126 (48%) were female, 134 (52%) were male. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients at diagnosis (age, sex, phase of CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, blast crisis), method of diagnosis (cytogenetics, FISH, PCR), comorbidities (age-adjusted CCI)).

Diagnosis

At initial diagnosis bone marrow biopsy was performed in 212 patients (82%). Karyotyping was applied in 225 patients (87%), FISH-analysis in 157 (60%). PCR-testing was performed in 205 patients (79%). Hence 260 patients (100%) received cytogenetics and/or FISH-analysis and/or PCR-testing during diagnostic work-up. 254 patients (98%) were in chronic phase, 5 (2%) in accelerated phase and 1 (0.4%) in blast crisis. EUTOS score could be calculated in 130 pts (50%), of these 20% were high risk, 80% low risk. Comorbidities according to the age-adjusted CCI were: CCI 2: 75 patients, 29%, CCI 3–4: 88 patients, 34%, CCI 5–6: 64 patients, 25% and CCI ≥ 7: 33 patients, 13%.

Molecular monitoring

Molecular monitoring by quantitative PCR was performed in 79% of patients at diagnosis and increased during the course of the observation: 2001–2006: 70%; 2007–2011: 92%; 2012–2015: 91%. Follow-up PCR-analysis was performed in 90% of patients; 2001–2006: 82%, 2007–2011: 98%, 2012–2015: 89%. Preferentially patients were monitored every 3 months (median: 97 days). The mean frequency of PCR-analysis per patient per year increased during the course of the observation: 2001–2006: 2.7; 2007–2011: 3.5; 2012–2015: 4.1. Reasons for no or incomplete molecular monitoring were missing data from hospitals and patient frailty.

Treatment and response

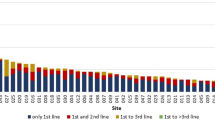

248 pts (95%) received some form of TKI-therapy. 194 chronic-phase-patients received a TKI as 1st line therapy, 66 patients, mostly diagnosed before 11/2001, received some other form of 1st line therapy. 1st line TKI treatment was imatinib in 197 pts (79%), 51 pts (21%) received a second generation TKI (14% nilotinib, 6% dasatinib). 2nd line TKI treatment consisted of dasatinib in 59%, nilotinib in 32%, imatinib in 6% and bosutinib in 3%. 3rd line TKI treatment was nilotinib in 56%, dasatinib in 35%, ponatinib in 6% and imatinib in 3%. 62 patients (24%) were treated within a study protocol. 248 patients received 413 TKI-therapies in first and further lines. The median number of TKI-therapy lines per patient was 1 (1–5). Reasons for changing the TKI-therapy were side effects in 48%, resistance in 26% and patients' wish in 5%. Missing data amounted to 21%. Out of 413 TKI-therapies 308 (75%) were monitored by PCR and 148 (36%) by cytogenetics.

One hundred sixty-four patients received no molecular monitoring after 12 months of TKI-therapy; 64 of the remaining 84 patients (76%) achieved a MMR or CMR at this time point. In 97 out of 146 patients (66%) who were diagnosed 2007 or later a molecular response could be retrieved after 12 months of TKI treatment; 75 of these patients (77%) achieved a MMR or CMR.

During the whole treatment period of 248 patients receiving TKI-therapy, molecular follow-up-monitoring was performed differently in participating institutions. Overall 75% (55%-100%) of therapies were monitored by cytogenetics, FISH or PCR. 114 cytogenetic responses could not be retrieved during the whole treatment period. 105 patients (78%) of the remaining 134 patients achieved a CCyR, 12 patients (9%) a PCyR. Five (4%) a minCyR and five (4%) a mCyR. Seven patients (5%) did not achieve a cytogenetic response. Out of 210 patients for whom molecular responses could be retrieved 89 (42%) achieved a CMR and 90 (43%) a MMR, 31 (15%) showed no molecular response. Median time to MMR / CMR was 8.2 months (0.6–147.7).

Multivariate analysis revealed that response to TKI-therapy did not correlate with patient age or comorbidities according to CCI. 12 patients (5%) received no TKI-therapy for a variety of reasons (allogeneic transplant, CCyR while on interferon therapy, life expectancy < 6 months, patient refusal). 12 pts (5%) received an allogeneic transplantation. Table 2 provides treatment information.

Figure 1 shows treatment responses according to molecular monitoring: CMR (<MR 4.5), MMR (<MR 3.0 > MR 4.5), no MR

Survival analyses

Overall survival probability of the whole cohort was 87% after 5 years, 80% after 8 years and 72% after 10 years. Overall survival probability after 5 years according to CCI 2, 3–4, 5–6, and ≥ 7 was 100, 91, 82 and 59%, after 8 years was 100, 90, 59 and 54% and after 10 years was 100, 84, 46 and 43%. Overall survival probability of 194 patients with chronic phase who received 1st line TKI-therapy was 87% after 5 years, 80% after 8 years and 74% after 10 years. Overall survival probability after 5 years according to CCI 2, 3–4, 5–6, and ≥ 7 was 100, 92, 77 and 66%, after 8 years was 100, 89, 52 and 59% and after 10 years was 100, 83, 52 and 39%. Overall survival of the patients according to initial molecular response (CMR, MMR, no MR) was 86, 94 and 79% after 5 years; 86, 90 and 61% after 8 years and 77, 83 and 40% after 10 years.

Figure 2 shows overall survival probability of chronic phase patients with 1st line TKI-therapy.

Overall Survival (OS) for all patients who were diagnosed in chronic phase in November 2001 or later and received a TKI as 1st line treatment. TOTAL (N = 191); median not yet reached (1.0–12.8+). Charlson Score 2 (n = 53); median not yet reached; all cases censored. Charlson Score 3–4 (n = 67); median not yet reached (1.8–12.8+). Charlson Score 5–6 (n = 44); median not yet reached (0.3–11.7+). Charlson Score > 6 (n = 27); median: 8.9 years (1.6–12.5+)

Progression free survival probability of 194 patients with chronic phase who received 1st line TKI-therapy was 79% after 5 years, 71% after 8 years and 68% after 10 years. Progression free survival probability after 5 years according to CCI 2, 3–4, 5–6, and ≥ 7 was 95, 79, 73 and 53%, after 8 years was 95, 71, 54 and 45% and after 10 years was 95, 65, 54 and 45%. Figure 3 shows progression free survival probability of chronic phase patients with 1st line TKI-therapy.

Progression Free Survival (PFS) for all patients who were diagnosed in chronic phase in November 2001 or later and received a TKI as 1st line treatment. TOTAL (N = 190); median not yet reached (0.7–12.8+). Charlson Score 2 (n = 53); median not yet reached (1.7–12.6+). Charlson Score 3–4 (n = 66); median not yet reached (0.7–12.8+). Charlson Score 5–6 (n = 44); median not yet reached (0.3–11.7+). Charlson Score > 6 (n = 27); median: 5.7 years (0.4–12.5+)

Comparison of OS and PFS between the 62 patients treated within a German CML-study [15] and patients treated outside a study protocol revealed a statistically significant difference in OS (p = .030) but not in PFS. 5 year OS of the patients who were treated within the German CML-IV study was 91% as compared to 86% of patients who received routine care. 5 year PFS of the patients who were treated within the German CML-IV study was 86% as compared to 75% of patients who received routine care. During follow up until December 2015 54 patients (21%) have died. 13 patients (5%) died of CML, one patient (0.4%) due to therapy related toxicities. 13 patients (5%) died of other causes, 20 patients (8%) due to comorbidities and for seven patients (3%) the cause of death couldn't be captured. Whether patients died due to comorbidity was strongly correlated to the age-adjusted CCI at diagnosis: CCI 2: 3% of patients died, CCI 3–4: 16% of patients died, CCI 5–6: 38% of patients died, CCI ≥ 7: 42% of patients died.

Discussion

The prognosis of patients suffering from CML has made major improvements since the introduction of TKI's into clinical practice [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. An international expert panel has established The European LeukemiaNET (ELN) recommendations to help hematologists tailoring therapy in an optimal way for the individual patient diagnosed with CML [8,9,10]. First line therapy in chronic phase should consist of imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib with the treatment goal of achieving CCyR or MMR after 12 months of therapy [10]. Second line therapy should include any one of these TKI's which had not been used in first line therapy. More important than using a special TKI is the close monitoring of treatment milestones using cytogenetics or PCR [10]. Optimal treatment response is achieved if a PCyR is achieved after 3 months and a CCyR after 6 months and thereafter of TKI-therapy. When using PCR, the response is optimal when BCR-ABL1 is reduced to <10% after 3 months, <1% after 6 months and <0.1% after 12 months and thereafter [10]. Patients needing third line therapy can be treated with bosutinib or ponatinib. Ponatinib is the only TKI today which can achieve long term remissions in patients carrying the T315I-mutation [7]. Patients needing third line therapy should also be counseled for an allogeneic transplant if the patient is suitable for this procedure [10]. A newly diagnosed patient with CML should, whenever possible, be treated within a prospective trial. However different reasons like severe comorbidities, special comedications, inclusion and exclusion criteria and patient wishes preclude many patients from entering a study. Therefore it is of importance not only to focus on results from randomized controlled trials but also to monitor the treatment patients receive in routine care. Outcome research from community-based CML-therapy can answer questions whether treatment recommendations are followed and whether patients receiving routine care have the same profit compared to patients who receive treatment within a trial. Our retrospective outcome research sheds light on the treatment reality of CML-patients in routine care in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate since market approval of imatinib in November 2001 and, in the meantime, the approval of four other TKI's for CML-treatment in first and further lines.

Diagnostic and follow-up-evaluation

100% of the patients studied received some form of molecular diagnostics either by cytogenetics, FISH or PCR at diagnosis as suggested by the ELN. Recommendations concerning molecular follow up were met only in part. Only 37% of the patients received molecular monitoring 12 months after the start of TKI-therapy. During the whole treatment period of 248 patients receiving TKI-therapy, molecular follow-up-monitoring was performed differently in participating institutions. Overall 75% (55–100%) of therapies were monitored by cytogenetics, FISH or PCR. In 97 out of 146 patients (66%) who were diagnosed 2007 or later a molecular response could be retrieved after 12 months of TKI treatment; 75 of these patients (77%) achieved a MMR or CMR. ELN-recommendations were first published in 2006 and updated in 2009 and 2013 [8,9,10]. The increasing usage of molecular monitoring after publication confirms that ELN-recommendations are followed increasingly in routine care. Nonetheless molecular monitoring has to be improved even further. Reasons for lower molecular monitoring are probably multifactorial:

-

1.

Our study was retrospective and many patients were diagnosed and partially followed in hospitals before they were cared for in a community-based oncology practice. A considerable amount of hospital files could not be retrieved.

-

2.

35% of patients were diagnosed before the first report of the ELN-recommendations in 2006.

-

3.

Our patient cohort is significantly older and has more comorbidities as compared to patients who are normally treated in CML-studies (e.g. IRIS or CML IV) [16, 17]. Therefore molecular monitoring has been probably paused or stopped in severely sick or disabled patients with a short life expectancy.

These differences between ELN-recommendations and routine care have also been reported by the EUTOS population-based registry, where complete cytogenetic response could only be calculated in 64% of patients and time to first MMR in 54% [18]. In our patients EUTOS-score could only be calculated in 50%. Basophiles and spleen size below the costal margin were not documented in a significant number of patients. This may partly be due to the fact that in Germany spleen size is measured by ultrasound, which is more accurate than palpation. In newly diagnosed CML-patients of the EUTOS registry in less than 50% the spleen was palpable and in only 15% it was large [19].

Therapy

95% of our patients received some form of TKI-therapy. 1st line TKI therapy consisted in 79% of imatinib and in 21% of a second generation TKI (14% nilotinib and 6% dasatinib) as suggested by ELN. 2nd line TKI therapy consisted in 97% of patients of either dasatinib (59%), nilotinib (32%) or imatinib (6%). This is in line with a recent report from the EUTOS population based registry, where treatment data from 2212 chronic phase patients from 20 European countries were collected and analyzed between 2008 and 2013. 97% of patients received a TKI as 1st line therapy (imatinib 80%, nilotinib 13% and dasatinib 4%) [18].

Survival

With a median follow up of 7 years (0–24) OS and PFS after 5 years in chronic phase patients receiving 1st line TKI-therapy is 87% and 79% respectively, which is comparable to published trials. Studies using imatinib as first line therapy reported an overall survival of 83–97% after ≥ 5 years with a median follow of 3.2 up to more than 6 years. PFS in these studies ranged from 83 to 94% [17, 20,21,22,23,24,25].

OS of chronic phase patients in the EUTOS population-based registry is 92% after 30 months (CI: 91–93%) as compared to 94% after 36 months in our cohort. Patients in the EUTOS registry had a median age of 55 as compared to 60 in our cohort [18].

During our evaluation period 54 patients (21%) have died. 14 (5%) died due to CML and therapy related toxicities, 20 (8%) due to comorbidities, 13 (5%) due to other causes and for 7 (3%) the cause of death couldn't be captured. This is in line with data reported from the German CML IV-study showing that more patients die from comorbidities than from CML in the TKI-treatment era [16]. Death from comorbidities is strongly linked to the number and severity of comorbidities as shown in the CML IV-trial. Here OS was strongly linked to the age-adjusted CCI [16]. No negative effect was found on remission rates and progression to advanced phases of CML [16]. In our cohort we could confirm these findings showing that patients with a higher CCI had a much lower OS probability, although response to TKI-therapy was not impaired by comorbidities or age. The fact that age has no influence on long-term outcome of patients treated with imatinib has been shown by another study [26].

Ten year overall survival in the CML IV trial is 84%, compared to 72% in our cohort. This is caused by major differences between the patient groups: Median age in CML IV is 53 compared to 60 in our cohort. There are great differences in the age-adjusted CCI distribution between CML IV and our group (CCI 2: 39% versus 28%, CCI 3–4: 39% versus 35%, CCI 5–6: 15% versus 23%, CCI ≥ 7: 7% versus 13%). When we exclude patients with accelerated phase and blast crisis and compare chronic-phase-patients with identical age-adjusted CCI between CML IV and our patient group, we find comparable overall survival data after 8 years (CCI 2: 94% versus 100%; CCI 3–4: 89% versus 89%; CCI 5–6: 78% versus 52%; CCI ≥ 7: 46% versus 59%) [16].

Oral therapies are especially dependent on the adherence of the patients. In CML it has been shown that the main reason for suboptimal molecular responses is low adherence [27]. Looking at adherence in patients with metastatic solid tumors we could demonstrate high adherence in patients treated in an oncology group practice, which may be due to the trustful and constant patient-doctor-relationship [28]. From our experience adherence in CML-patients can be reinforced in the ambulant oncology setting through a constant patient-doctor-relationship, discussion of the medication plan at every visit, communication about tolerability, side effects and drug interactions of the TKI used, discussion of the results of molecular monitoring and the count of tablets prescribed and used per time period. After achievement of a CHR and good tolerability of the TKI patients are usually seen every 3 months for consultation, laboratory analysis and molecular monitoring.

The strength of our study is the fact that nine hematology-oncology practices with 26 hematologists took part and that all patients with the diagnosis of a Ph+/BCR-ABL1+ CML who received treatment between 11/2001 and 12/2015 were documented. Weaknesses are that not all of the oncology practices in Rhineland-Palatinate took part and that the study was retrospective.

Conclusions

In summary we could demonstrate with our outcome research in routine care that patients with CML who are cared for by community based hematologists receive diagnostic procedures at diagnosis and treatment as suggested by ELN. This leads to an OS and PFS in routine care that is comparable to international studies. Molecular follow-up should be improved according to ELN-recommendations.

Abbreviations

- AP:

-

Accelerated phase

- Ara-C:

-

Cytarabine

- BCR-ABL1+:

-

Breakpoint cluster region-Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 positive

- BP:

-

Blastic phase

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CCyR:

-

Complete cytogenetic response

- CHR:

-

Complete hematological response

- CML:

-

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- CMR:

-

Complete molecular response

- ELN:

-

European LeukemiaNET

- EUTOS:

-

European treatment and outcome study

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- mCyR:

-

Minor cytogenetic response

- minCyR:

-

Minimal cytogenetic response

- MMR:

-

Major molecular response

- MR:

-

Molecular response

- NCyR:

-

No cytogenetic response

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PCyR:

-

Partial cytogenetic response

- PFS:

-

Progression free survival

- Ph+:

-

Philadelphia chromosome positive

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

References

Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Mett H, Meyer T, Müller M, Druker BJ, Lydon NB. Inhibition of the Abl protein-tyrosine kinase in vitro and in vivo by a 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative. Cancer Res. 1996;56:100–4.

Capdeville R, Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Matter A. Glivec (STI571), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:493–502.

Cohen MH, Williams G, Johnson JR, Duan J, Gobburu J, Rahman A, et al. Approval Summary for Imatinib Mesylate Capsules in the treatment of chronic myelogenous Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:935–42.

Radich JP, Kopecky KJ, Appelbaum FR, Kamel-Reid S, Stock W, Malnassy G, et al. A randomized trial of dasatinib 100 mg versus imatinib 400 mg in newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(19):3898–905.

Cortes JE, Kim DW, Kantarjian HM, Brümmendorf TH, Dyagil I, Griskevicius L, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the BELA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3486–92.

Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, Etienne G, Lobo C, et al. ENESTnd Investigators. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2251–9.

Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, le Coutre P, Paquette R, Chuah C, et al. PACE-Investigators. A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1783–96.

Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, Hochhaus A, Simonsson B, Appelbaum F, et al. European LeukemiaNet. Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;108(6):1809–20.

Baccarani M, Cortes J, Pane F, Niederwieser D, Saglio G, Apperley J, et al. European LeukemiaNet. Chronic myeloid leukemia: an update of concepts and management recommendations of European LeukemiaNet. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):6041–51.

Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, Hochhaus A, Soverini S, Apperley JF, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122(6):872–84.

BNHO. Berufsverband der Niedergelassenen Hämatologen und Onkologen in Deutschland (Association of registered hematologists and oncologists in Germany). http://www.bnho.de/startseite.html (2012). Accessed 19 May 2016.

Kompetenznetz Leukämien. Ergebnisse der randomisierten CML-Studie IV (Competence network acute and chronic leukemias; results from the randomized CML study IV). http://www.kompetenznetz-leukaemie.de/content/studien/studiengruppen/cml/projekte/cml_iv/ (2015). Accessed 15 Jun 2016.

Hasford J, Baccarani M, Hoffmann V, Guilhot J, Saussele S, Rosti G, et al. Predicting complete cytogenetic response and subsequent progression-free survival in 2060 patients with CML on imatinib treatment: the EUTOS score. Blood. 2011;118(3):686–92.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–51.

Saussele S, Krauss MP, Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Proetel U, Kalmanti L, et al. Schweizerische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Klinische Krebsforschung and the German CML Study Group. Impact of comorbidities on overall survival in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia: results of the randomized CML Study IV. Blood. 2015;126:42–9.

Hochhaus A, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Druker BJ, Branford S, Foroni L, et al. IRIS Investigators. Six-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(6):1054–61.

Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Hasford J, Castagnetti F, Di Raimondo F, Casado LF, et al. Treatment and outcome of 2904 CML patients from the EUTOS population-based registry. Leukemia. 2016. doi:10.1038/leu.2016.246.

Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Hasford J, Lindoerfer D, Burgstaller S, Sertic D, et al. The EUTOS population-based registry: incidence and clinical characteristics of 2904 CML patients in 20 European countries. Leukemia. 2015;29:1336–43.

de Lavallade H, Apperley JF, Khorashad JS, Milojkovic D, Reid AG, Bua M, et al. Imatinib for newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: incidence of sustained responses in an intention-to-treat analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3358–63.

Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, Goldberg SL, Powell BL, Giles FJ, Wetzler M, et al. Rationale and Insight for Gleevec High-Dose Therapy (RIGHT) Trial Study Group. High-dose imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: high rates of rapid cytogenetic and molecular responses. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4754–9.

Cervantes F, López-Garrido P, Montero MI, Jonte F, Martínez J, Hernández-Boluda JC, et al. Early intervention during imatinib therapy in patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a study of the Spanish PETHEMA group. Haematologica. 2010;95(8):1317–24.

Faber E, Mužík J, Koza V, Demečková E, Voglová J, Demitrovičová L, et al. Treatment of consecutive patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in the cooperating centres from the Czech Republic and the whole of Slovakia after 2000 - a report from the population-based CAMELIA Registry. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87(2):157–68.

Gugliotta G, Castagnetti F, Palandri F, Breccia M, Intermesoli T, Capucci A, et al. Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto CML Working Party. Frontline imatinib treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: no impact of age on outcome, a survey by the GIMEMA CML Working Party. Blood. 2011;117(21):5591–9.

Kim D, Goh HG, Kim SH, Choi SY, Park SH, Jang EJ, et al. Comprehensive therapeutic outcomes of frontline imatinib mesylate in newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients in Korea: feasibility assessment of current ELN recommendation. Int J Hematol. 2012;96(1):47–57.

Rosti G, Iacobucci I, Bassi S, Castagnetti F, Amabile M, Cilloni D, et al. Impact of age on the outcome of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in late chronic phase: Results of a phase II study of the GIMEMA CML working party. Haematologica. 2007;92:101–5.

Marin D, Bazeos A, Mahon FX, Eliasson L, Milojkovic D, Bua M, et al. Adherence is the critical factor for achieving molecular responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who achieve complete cytogenetic responses on imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2381–8.

Feiten S, Weide R, Friesenhahn V, Heymanns J, Kleboth K, Köppler H, et al. Adherence assessment of patients with metastatic solid tumors who are treated in an oncology group practice. Springerplus. 2016;5:270.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the communication of diagnostic and treatment data by the cooperating hematology-oncology group practices:

1. Praxisklinik für Hämatologie und Onkologie

Neversstraße 5, 56058 Koblenz

Hematologists: J. Heymanns, R. Weide, G. Chakupurakal, J. Thomalla, C. van Roye, H. Köppler

Medical Documentalists: K. Kleboth, V. Friesenhahn

2. Gemeinschaftspraxis für Hämatologie, Onkologie und Nephrologie

Kutzbachstraße 7, 54290 Trier

Hematologists: B. Rendenbach, H.-P. Laubenstein, C. Arnold

3. Onkologische Schwerpunktpraxis

Nordallee 1, 54292 Trier

Hematologists: M. Grundheber, P. Seibel-Bohlscheid

4. Internistische Gemeinschaftspraxis Hämatologie, Onkologie, Palliativmedizin

Wilhelm Leuschner Straße 11-13, 67547 Worms

Hematologists: O. Burkhard, B. Reimann, C. Lorentz

5. Onkologische Schwerpunktpraxis

Hilgardstraße 30, 67346 Speyer

Haematologists: J. Franz-Werner, H.P. Feustel, J. Behringer, L. Scheuer

6. Gemeinschaftspraxis für Hämatologie und Onkologie

Kelberger Str. 39, 56727 Mayen

Hematologists: M.-T. Keller, M. Maasberg, M. Schmitz, H. Gerner

7. Praxis für Hämatologie und Onkologie

Willi-Brückner-Str. 1, 56564 Neuwied

Hematologist: P. Ehscheidt

8. Schwerpunktpraxis Hämatologie und Internistische Onkologie

Leuzbacher Weg 31, 57610 Altenkirchen

Hematologist: J.W. Strehl

9. Schwerpunktpraxis für Hämatologie und Onkologie

Schneiderstr. 12, 67655 Kaiserslautern

Hematologists: R. Hansen, M. Reeb, S. Pfitzner-Dempfle

Funding

This study was supported by Megapharm, Germany, through a restricted grant. Megapharm had no influence on data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data were captured from the patients' treatment files. Additional data were not available.

Authors' contributions

All authors were involved in conception, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and in writing and finally approving of the manuscript.

Authors' information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All patients gave written informed consent for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the ethics committee of Rhineland-Palatinate (Germany) we were allowed to capture anonymized routine-care data. An ethical approval was therefore not necessary and hasn't been obtained.

All patients gave written informed consent for data documentation, collection and statistical analysis.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Weide, R., Rendenbach, B., Grundheber, M. et al. Standard of care of patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) treated in community based oncology group practices between 2001-2015 in Rhineland-Palatinate (Germany). Appl Cancer Res 37, 26 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41241-017-0031-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41241-017-0031-y