Abstract

The aim of this article is to establish the extent to which the concept of e-leadership has taken off as a lens through which to study leadership for technology-enhanced learning (TEL) in higher education. Building on a previous study conducted in 2013, this article thus covers an exploratory review of the literature for the period 2103-2017. It analyses 49 articles which explore both the specific concept of e-leadership as well as other work dealing more generally with leadership and organisational change for TEL in higher education. The findings show that while none of the empirical studies identified in the literature refer explicitly to e-leadership, there are a number of interesting insights to be found in the theoretical articles. The results also highlight the widely different interpretations and applications of the concept of e-leadership and the consequent need for the definition to be refined. The paper concludes with recommendations for further multidisciplinary research at the intersection of the fields of educational technology and educational management, focusing on values, strategy, organisation and leadership interactions at meso level, the economy and public policy at macro level, and teaching and learning at the micro level, as well as for research in Leadership Development for TEL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Technology has been part of the educational landscape for decades, and one could argue that even chalk and the blackboard are forms of technology appropriated for learning, as indeed are books. However, within the scope of this paper, the term technology is used to refer to digital technology as “a system that combines computers, telecommunications, software and rules and procedures or protocols” and media (text, graphics, audio and video, which involve the creation, communication and interpretation of meaning (Bates, 2015). Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL) is to be understood as the use of technology in any teaching and learning situation, on a continuum from face-to-face to fully online learning (Bates & Sangrà, 2011). The rapid pace of development of digital technologies has already disrupted many industries and sectors, most notably the music industry (Moreau, 2013; Rogers, 2013), hotels and taxis (D’Emidio, Dorton, & Duncan, 2015; Suzor & Wikstrom, 2016) and it is not infrequent to hear claims that the next area to be seriously challenged will be that of higher education (HE) (Barber, Donnelly, & Rizvi, 2013; Craig, 2015; Lucas Jr., 2016; Shirky, 2012), though Selwyn (2013) offers a critical analysis, as do Weller and Anderson (2013).

Universities in general, and European universities in particular, have survived in their more or less current form for several hundred years, yet currently face a number of challenges: the wide availability of knowledge on the web, massification and greater diversity of students, a decline in public funding coupled with rising student debt in many countries (Barber et al., 2013; Boyer, 2016; Staley & Trinkle, 2011). While technology is not the only solution to these challenges, it has been suggested that HE leaders need to develop a better understanding of the potential of TEL coupled with a high level of strategic thinking (Bates & Sangrà, 2011).

This is often associated with the theory of e-leadership, initially developed by Avolio, Kahai, and Dodge (2001) in the context of the business world, where e-leadership is defined as “a social influence process embedded in both proximal and distal contexts mediated by AIT [Advanced Information Technology] that can produce a change in attitudes, feelings, thinking, behavior, and performance.” (Avolio, Sosik, Kahai, & Baker, 2014) as updated from the initial definition (Avolio et al., 2001).

This study aims to establish the extent to which the concept of e-leadership has taken off as a lens through which to study leadership for TEL in HE. The approach taken is that of an exploratory literature review in that it aims to identify what research has been published in the period 2013-2017 in terms of theory, empirical evidence and research methods with respect to the topic in question. It is situated at the intersection of different disciplinary fields: leadership within the wider field of management and business studies, and TEL within the education and educational research field. It is thus necessary to establish the current state of knowledge at this point of overlap. As Jameson (2013) states:

…the many scholarly educational research and professional communities that span the liminal edges bordering the two fields of educational technology and leadership do not, for the most part, relate to or recognise each other’s work very much. (Jameson, 2013, pp. 891-892).

In addition to answering the primary research question of establishing the extent to which e-leadership has taken off as a lens through which to study leadership for TEL in HE, the results are also analysed in terms of the following secondary research questions:

-

What is the geographical distribution of research in the field? Is it concentrated in a particular region and, if so, are there any gaps to be filled?

-

In which disciplinary fields (journals) are these studies being published?

-

What thematic trends can be identified in comparison with those identified by Jameson (2013)?

-

What populations within HE (formal leaders, teachers, students,…) are being studied with respect to leadership for TEL? Are they considered in isolation or as part of a wider multi-stakeholder perspective?

-

What is the level of analysis (project level, single institution, multiple institutions)?

-

What methodologies are being applied?

Finally, if we understand leadership as a highly context-dependent social influence process, where there is a need to investigate “real organizational life” (Alvesson, 2017, p. 11) the last three questions are taken in combination to explore how this is taken into account through the methodology, the populations studied and the level of analysis.

The place of leadership in the literature on TEL and online learning

Examining the developments within TEL research over time, Winn (2002) defines four ages of such research as (1) instructional design with a focus on content; (2) differentiated message design focused on format, (3) simulation with a focus on learner control, interaction, scaffolding of student learning and constructivist principles; (4) a focus on technology-supported artificial learning environments, distributed cognition and the social nature of learning in communities. In the period 2002-2014, Baydas, Kucuk, Yilmaz, Aydemir, and Goktas (2015) identify a focus mainly on learning approaches/theories and (online) learning environments, albeit in a literature review restricted to two UK journals (BJET, the British Journal of Educational Technology and ETR&D, Educational Technology Research and Development).

In the field of distance and online education, Zawacki-Richter and Naidu (2016) identify waves of alternating institutional and individual research over the past 35 years from articles published in the journal Distance Education: professionalization and institutional consolidation (1980–1984), instructional design and educational technology (1985–1989), quality assurance in distance education (1990–1994), student support and early stages of online learning (1995–1999), the emergence of the virtual university (2000–2004), collaborative learning and online interaction patterns (2005–2009), and interactive learning, MOOCs and OERs (2010–2014). It would thus seem that the next institutional wave is somewhat overdue.

Indeed, in an extensive literature review covering the period 2000 to 2013, in both the management and the education fields, Jameson (2013) concludes with a call for a 5th age in educational technology research, where e-leadership in higher education is the focus.

Updating Jameson’s 2013 literature review

In order to bring the literature review up to date and provide a current picture of the state of the art, searches were carried out in four major databases between October 2017 and February 2018, for the period 2013-2017.

Method

Jameson used the following combinations of search terms:

-

A)

e-leadership AND “higher education” AND “educational technology”

-

B)

leadership AND “higher education” AND “educational technology”.

For the purposes of updating the literature review for the period 2013-2017, these same combinations were used in ISI Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC (selected for their relevance to the field) and Google Scholar (selected in order to widen the search as far as possible).

In order to check for results which may not have been found through the two aforementioned combinations and, given the complexity of conducting literature review in the field of educational technology due to the wide variety of terms used by researchers and practitioners (Pretto & Curró, 2017), a concept map (Keeble & Kirk, 2007) was created in order to delimit the study (Fig. 1). The central topic of (e-)leadership was broken down into three main components in order to:

-

identify synonyms or alternative terms relevant for extending the search, in particular with respect to TEL;

-

identify key authors from both the leadership and TEL fields for the theoretical background;

-

to delimit the study in terms of education sector (HE) and to facilitate exclusion of non-relevant results.

With respect to these exclusions, a prior initial search resulted in a high number of results pertaining to school leadership, leadership education programmes, health leadership and virtual team leadership, all of which were deemed out of scope for this literature review.

Finally, the concept map included an identification of populations in HE concerned with TEL leadership, as both leaders and followers, as well as of the different levels of analysis. These last two areas were used to categorise the results in the analysis phase.

In referring to the challenges of conducting literature reviews in the IT, ICT and educational technology fields, Pretto and Curró (2017) draw attention to the need for judicious selection of key search terms. With respect to educational technology, the authors list commonly-used alternatives such as technology-enhanced learning (TEL), digital technologies, instructional technology, blended learning, online learning, digital learning, while Wheeler (2012) identifies the use of TEL, e-learning and digital learning. Bayne (2015) points out that TEL is quite specific to the UK, with some usage in European contexts, and that on a global scale the terms ‘instructional technology’, ‘educational technology’ and ‘e-learning’ still dominate. While the importance of assumptions behind the use of particular terms needs to be recognised, as highlighted by both Pretto & Curró and Bayne, a full analysis of these is beyond the scope of this current study.

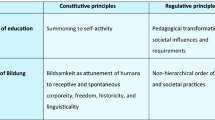

Finally, in addition to the aforementioned concept map, the TEL e-leadership framework developed by Jameson (Fig. 2) was taken as the basis for conducting a trend analysis, checking for reference to the existing concepts as well as for additional themes emerging from the literature in the period 2013-2017.

e-Leadership framework for educational technology in higher education (Jameson, 2013, p. 911)

Results

Overall, the search resulted in the following initial results (Table 1).

A total of 843 results were screened based on title, keywords and abstract (where available). The results from all searches were first winnowed down to exclude those not covering leadership or related concepts at all. A second winnowing excluded results which were considered off-topic, dealing with schools, the health sector, gaming or information systems. The Google Scholar search proved the most challenging, as despite the inclusion of higher education and an attempt to filter out books and schools, these still appeared in the results, alongside results pertaining to business. Another issue with the Google Scholar search was in bringing up results which had clearly not been peer-reviewed and the impossibility of defining this in the search criteria. Given the time frame for this study, it was only feasible to screen the first search for “e-leadership” AND “higher education” AND “education* technology” within the first 100 results obtained via Google Scholar, and the first 20 results of the other searches.

The final results, after identifying duplicates obtained via different searches and across the different databases, are as follows:

Forty-nine articles, 48 of which we can be confident have been peer-reviewed. The non-peer-reviewed result is a concept paper (Brown, Czerniewicz, Huang, & Mayisela, 2016) retained for its highly relevant selection and analysis of digital education leadership competency and literacy frameworks. Identified via the Google Scholar search, its status was checked in ERIC which only produced it as a result after including non-reviewed papers in the search.

After detailed analysis of the main body of the articles, and in particular of the methodology section where present, the results were classified according to the following three categories: empirical studies (where clearly-defined populations were studied according to recognised research methodologies); theoretical analyses (reviews of leadership and related theories, applied to higher education but with no empirical study); and opinion pieces (articles expressing author’s opinions based on personal experience with no or only nominal reference to underlying theory). These categories can be related to the main types of scientific publication, where empirical studies come under the umbrella of research papers or original research, theoretical analyses belong to the ‘review article’ category and opinion pieces can be considered as viewpoints (Öchsner, 2013). As such viewpoints or opinion papers are not always peer-reviewed, the status of all results obtained in this category was double-checked in ERIC, confirming that they had indeed been peer-reviewed.

The non-empirical studies (theoretical articles and opinion pieces) were included in this literature review to give a fuller picture of the type of research being published in the field of (e)-leadership for technology-enhanced learning in higher education. More specifically, theoretical articles can provide insights into how scholars are approaching the question from a broader angle, and opinion pieces can give insights into the preoccupations of leaders and other stakeholders as they reflect on challenges and leadership practice from a strategic or organisational perspective.

The 49 results are thus comprised of:

-

27 empirical studies (ES), one of which from 2013 had already been identified by Jameson (Garrison & Vaughan, 2013)

-

16 theoretical analyses (TA)

-

6 opinion pieces (OP)

Figure 3 below presents the number and type of results per year of publication.

While empirical studies are the most widely represented in total over the 5-year period (55%), no obvious trend in the development of such research can be detected in the results, apart from a peak in 2015. Theoretical analyses, which often propose models that have not been tested empirically, appear to be relatively popular forms of presenting research about e-leadership in higher education (33%), followed by opinion pieces (12%).

Two major differences with respect to Jameson’s 2000-2013 literature review should be noted here: firstly, the inclusion of opinion pieces which reflect how and where (e-)leadership is being written about in relation to TEL in HE, and secondly that only results pertaining to higher education were retained, whereas Jameson included results from other phases of education due to the lack of results obtained for HE.

Detailed presentation of results

The following three tables present a summary of the results, organised into the three categories. The tables provide the reference of the publication, information about location, population, context and methodology together with a summary of the findings (Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Analysis of results

From the three aforementioned tables, the empirical studies were analysed from the perspectives of geographical location, methodologies used and populations studied in relation to leadership, in order to answer the corresponding secondary research questions indicated earlier. Additional analysis identified the leadership theories or terms associated with leadership for the overall results. A series of concept matrices (Webster & Watson, 2002) were used in order to perform this analysis, to identify themes and trends and to produce the associated tables and figures.

Empirical studies 2013-2017

In terms of location, the spread across geographical regions was reasonably equitable, as shown in Table 5 below:

It should be noted that four of the six European studies were located in the UK and one other covered three European countries (Finland, Spain and the Czech Republic) as part of an ERASMUS+ project.

Turning now to populations, three main clusters of focus were identified:

-

1)

governance and senior leaders: 9 results,

-

2)

non-governance stakeholders (teachers, teachers and students, instructional designers): 8 results,

-

3)

holistic multi-stakeholder approaches at different levels (project, faculty, single institution, multiple institution): 10 results.

Cluster 1 consists of studies focussed on leadership from the perspective of formal leaders: faculty governance (Ciabocchi, Ginsberg, & Picciano, 2016), university administrators (Livingstone, 2015; Spackman, Thorup, & Howell, 2015), senior leaders (Akcil, Aksal, Mukhametzyanova, & Gazi, 2017; Holt, Palmer, Gosper, Sankey, & Allan, 2015), online education administrators (Burnette, 2015) or through the mobilisation of local and international experts (Davis & Higgins, 2015; Díaz & Báez, 2015).

Cluster 2 results studied leadership from the perspective of stakeholders who are not themselves in TEL leadership roles: change management from teachers’ perspective (Sheiladevi & Rahman, 2016); teachers’ perceptions of organisational culture (Zhu, 2015), related to a previous study involving both teachers and students (Zhu & Engels, 2014); futures visioning with deans and lecturers (Inayatullah & Milojevic, 2014); instructional designers and e-learning production staff (Ashbaugh, 2013; Tay & Low, 2017) students’ perceptions of leadership in online instructors (Bogler, Caspi, & Roccas, 2013).

Cluster 3 studies took a holistic multi-stakeholder approach at project-level (Brown, 2013; Garrison & Vaughan, 2013; Stoddart, 2015), faculty or department level (King & Boyatt, 2015; Trevitt, Steed, Du Moulin, & Foley, 2017) or institution-wide, with one focussing on a single institution (Roushan, Holley, & Biggins, 2016) and four taking a multiple-institution approach (Cifuentes & Vanderlinde, 2015; Domingo-Coscollola, Arrazola-Carballo, & Sancho-Gil, 2016; Ng’ambi & Bozalek, 2013; Singh & Hardaker, 2017).

A variety of methodologies were also mobilised:

-

16 qualitative studies, taking different approaches such as semi-structured interviews, action research, phenomenology, community of inquiry and narrative inquiry;

-

9 quantitative studies;

-

2 mixed methods approaches.

Five of the qualitative approaches were presented as case studies, as was one of the mixed methods studies. It should be noted here that the latter (Livingstone, 2015) relied solely on an online survey and included personal criticism of the institution with value-laden language. A further case study (Brown, 2013) makes no explicit reference to the methodology used and it was not possible to determine this from a detailed reading of the article.

If we now compare the methodologies used to the populations studied, we find that nine of the ten holistic multi-stakeholder approaches used or included qualitative methods (Table 6).

Finally, taking into account Jameson’s observation of a lack of dialogue between the two fields of education technology research and education management research, it is worth looking at the type of journal in which these empirical studies have been published:

-

15 studies were published in education technology journals,

-

6 studies were published in education management journals.

The remaining studies were distributed among journals focusing on science and technology education (3), media education (1), education and teaching (1), productivity and performance (1).

Interestingly, one of the studies by Zhu (Zhu & Engels, 2014) was published in an education management journal, the other (Zhu, 2015) in an education technology journal, perhaps showing the will to bridge this divide between the two fields.

Theoretical analyses 2013-2017

Three of the results provide an analysis of leadership theories in relation to the integration of technology for teaching and learning, taking e-leadership as understood in business and relating it to the field of education (Mishra, Henriksen, Boltz, & Richardson, 2016), or developing a model of TEL leadership (Markova, 2014).

Others focus on the acceptance of technology by HE teaching staff with recommendations for HE leadership to integrate the implications of different models of technology acceptance (Rogers’ (1962, 2003) diffusion model, Davis’ (1989) technology acceptance model and Mishra and Koehler’s (2006) technological, pedagogical and content knowledge TPACK model) in Continuous Professional Development (Sutton & DeSantis, 2017).

In particular Van Wart, Roman, Wang, and Liu (2017) propose widening the notion of e-leadership from leading in virtual spaces to include the act of choosing, recommending and supporting the implementation of ICT for an organisation, and propose a framework for connecting the different literatures in the fields of e-leadership and technology adoption.

Boyd and Sampson (2016) reflect on initiatives aimed toward developing staff digital confidence, an approach which is also found in Brown et al. (2016), who present conceptions of digital literacy and digital education as motivations for the conceptualisation of a proposed curriculum framework for digital education leadership.

Of significant interest is the approach proposed by McCutcheon (2014). This entails applying the UK National Health Service (NHS) Nursing Leadership Framework to structure and guide the process of developing e-learning for postgraduate nursing education. This framework is organised into seven dimensions around the central aim of delivering the service: demonstrating personal qualities, working with others, managing services, improving services, setting direction, creating the vision, delivering the strategy.

In reviewing research on Quality and Leadership of Online Education, Gupton (2014) examines the need for leadership as the online delivery of education develops, but uses emotional and value-laden language. Mukerjee (2014) explores the concept of organisational agility, while Murphy (2016) formulates an argument for the recognition of the importance of the mid-level professional manager in transitioning bottom-up to institute-wide TEL initiatives.

Finally, in the field of Organisational Learning, Tintoré and Arbós (2013) propose an Organisational Capacity Model questionnaire for identifying the stage of growth in the organisational learning capacity of a university, covering individual learning and institutional learning (teamwork, leadership and vision, culture and values, structures, resources, openness to the environment, barriers to learning). As with Khanna’s (2017) good governance framework, Díaz and Báez’s (2015) instrument for exploring leadership capabilities for ICT in education, Markova’s (2014) TEL leadership model and Jameson’s (2013) e-leadership framework for TEL, no evidence of the application of this tool in empirical studies has been identified.

Opinion pieces 2013-2017

The six opinion pieces identified in the literature view are presented briefly here to provide a picture of the preoccupations of HE leaders and other stakeholders who are taking an interest in the question of leadership for TEL in HE. Beaudoin (2016) presents an overview of current issues related to distance learning in HE, identifying central questions, issues, challenges and opportunities to be addressed by decision makers, as well as key attributes of effective leaders, which can be classified as leadership style and vision (transformational, change-management rather than technology as the priority, tolerance for ambiguity and risk); critical (assessment of situations, using data, resisting fashion, focus on both micro and macro perspectives); pedagogical (sound knowledge of distance education and theory, advocacy, decide and act as learner-centered educator); networking (to share ideas, strategies and resources).

Based on personal experience as an HE leader, Moccia (2016) presents a six-point strategy to help HE leaders reinvent their industry: be global, financially sustainable, value-added, technological-oriented, a strategic local partner, substance more important than form. Similarly, Persichitte (2013) builds on personal experience to present TEL leadership recommendations terms of context, behaviours and skills. Chow (2013) gives a detailed and honest account of the adaptation necessary in his move from Dotcom leadership to a HE environment, in particular the need to develop systems thinking and to focus on the human aspects, bringing stakeholders together to discuss issues and find solutions.

From the Information Technology (IT) perspective, Brown (2014) argues for IT departments to play a strategic role in the development of teaching and learning innovation, implying rethinking the roles of the chief information officer (CIO) and the academic technologist, the latter group also being reflected in Watson and Watson’s (2013) argument for educational technologists to be seen as key change agents.

Leadership theories

While the purpose of this paper is not to provide a comprehensive review of leadership theory itself, it is still important to look more closely at which leadership theories and concepts are being referred to in the results identified in this literature review. As can be seen from the graph below (Fig. 4) the main theories cited are transformational leadership, distributed leadership and e-leadership.

Stewart (2006) provides a detailed account of the evolutions in transformational leadership theory, tracing it back to its origins in the seminal work of Burns (1978) who identified two types of leadership: transactional and transformational. While transactional leadership involves the leader exchanging something of value with the follower, transformational leadership “looks for potential motives in followers, seeks to satisfy higher needs, and engages the full person of the follower” (Burns, 1978, p. 4). In this case there is a search for mutually beneficial solutions with an increase in commitment and capacity to achieve mutual purposes.

Transactional and transformational leadership are not necessarily diametrically opposed, as can be seen in the development of Full Range Leadership Theory or FRLT (Bass & Avolio, 1997) where leaders mobilise a variety of behaviours in order to obtain greater commitment from followers.

Distributed leadership theory first emerged as a concept in the mid 1950s (Gibb, 1954) and a significant body of work on distributed leadership of educational organisations has been developed since the beginning of the 2000s (Bolden, 2011; Bolden, Gosling, & Petrov, 2009; Gronn, 2002, 2008; Harris, 2008; Harris & Spillane, 2008; Spillane, 2012; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2004). However, as Tian, Risku, and Collin (2016) point out, there is no universal accepted definition, proposing that “distributed leadership be defined and studied in terms of leadership as a process that comprises both organisational and individual scopes; the former regards leadership as a resource and the latter as an agency. Both resource and agency are considered to emerge and exist at all organisational levels.” (Tian et al., 2016, p. 158).

As mentioned in the introduction to this study, e-leadership theory refers to “a social influence process embedded in both proximal and distal contexts mediated by AIT that can produce a change in attitudes, feelings, thinking, behavior, and performance” (Avolio et al., 2014). The different understandings of e-leadership in relation to TEL are discussed later in this article.

The results also cite other concepts associated with leadership which are not necessarily theories in their own right: top-down, bottom-up, middle-out, formal, informal, structured, supportive, passive (the latter coming under the umbrella of FRLT).

The following chart (Fig. 4) shows the frequency of occurrence of each of these theories and concepts according to the type of result.

It should be noted here that the ‘distributed’ label also encompasses other terms, such as ‘distributive’, ‘collaborative’, participatory’, ‘participative’ and that these concepts may not necessarily always refer to the same theory or understanding. Furthermore, the concepts of supportive and structured leadership were only used in two articles relating to the Chinese context (Zhu, 2015; Zhu & Engels, 2014). Finally, several articles, including empirical studies, make no mention of the underlying leadership theory, as is the case of Garrison and Vaughan (2013), despite references to both collaborative and distributed leadership, and of Watson and Watson (2013), who refer to universities as complex systems yet do not make any reference to complexity leadership theory (Arena & Uhl-Bien, 2016; Clarke, 2013; Hazy & Uhl-Bien, 2015; Uhl-Bien, Marion, & McKelvey, 2007).

Other theories not directly related to the field of leadership are used to shed light on the question. In particular Singh and Hardaker (2017) apply Giddens’ (1984) Theory of Structuration to identify a set of change levers at the intersection of bottom-up and top-down initiatives, namely the promotion of a collaborative, participatory approach, helping to form social networks so that potential adopters learn from peers, combining mass and interpersonal communication, endorsing bottom-up engagement and recognising the cultural specificity of faculties and departments.

Van Wart et al. (2017) and Sutton and DeSantis (2017) draw on the technology adoption literature, while Ng’ambi and Bozalek (2013) refer to Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 2003; Rogers & Scott, 1997). Brown (2013) and Shieladevi and Rahman (2016) take a change management perspective. Other theories taken from the management field include learning organisations (Trevitt et al., 2017) and lean management (Tay & Low, 2017).

Perhaps the most significant observation here is that none of the empirical studies actually refer explicitly to e-leadership. We can thus conclude that there is a distinct lack of empirical research in e-leadership for TEL in HE. In those results which did cite e-leadership, the most widely used theories associated with e-leadership were again distributed and transformational, as can be seen in Fig. 5 below.

Discussion

This exploratory literature review was conducted in order to determine the extent to which the concept of e-leadership has taken off a lens through which to study leadership for technology-enhanced learning in higher education. Both the prevalence and the relevance of the use of this concept are discussed below. Trends are identified with respect to Jameson’s (2013) e-leadership framework for TEL. Finally, recommendations for further research are formulated to bridge the gaps identified by the interrelated secondary research questions of populations studied, methodologies applied and levels of analysis, as well as in terms of (inter)disciplinarity.

(Re-)defining e-leadership

As we have already noted, none of the empirical studies identified in the search actually cite e-leadership, although there is a certain amount of interest among the theoretical papers. We might conclude that e-leadership for technology-enhanced learning in higher education has not taken off as a field of research, but before jumping to such a conclusion it is worth taking a closer look at the concept of e-leadership itself. If we take the strict definition of e-leadership as referring to “a social influence process embedded in both proximal and distal contexts mediated by AIT that can produce a change in attitudes, feelings, thinking, behavior, and performance” (Avolio et al., 2014) and then unpack it, we can see that one of the elements in particular, the notion of ‘social influence processes… mediated by AIT’, might not always be present in the leadership relationships we are studying.

We can take the teaching and learning process to be mediated by AIT in TEL, and therefore see that the application of e-leadership theory is relevant to the topic of leading in online environments (Phelps, 2014). However, the leadership interventions, behaviours and attitudes of higher education governance and academic leaders in strategic thinking and decision-making around TEL are themselves not necessarily mediated by technology, although they may be. One perspective which shows promise in this respect is that put forward by Van Wart et al. (2017), of bringing together the literatures on e-leadership and technology adoption within the following wider definition of e-leadership as “the ability to effectively select and use ICTs for both personal and organizational purposes” (Van Wart et al., 2017, p. 529). While the focus here is on ICT adoption from a general organisation perspective, the further application of this approach to TEL in a higher educational setting is a logical next step, resonating with another educational leadership definition of e-leadership, namely as “the effective promotion and integration of technological learning and literacy into and within [educational] environments” (Preston et al., 2015, p. 991).

In analysing online education administrators’ struggles for authority in the higher education landscape, Burnette (2015) quotes Beaudoin’s (2002) definition of distance education leadership, namely as “a set of attitudes and behaviors that create conditions for innovative change, that enable individuals and organizations to share a vision and move in its direction, and that contribute to the management and operationalization of ideas” (Beaudoin, 2002, p. 132). This definition could in fact apply to leadership for change in general, although certain components of it are reflected in the some of the main trends identified in the present study (see also Fig. 6 below), in particular e-leadership visioning, change management and strategic planning.

Some authors accept the concept of e-leadership as multifaceted and conceptually ambiguous (Gurr, 2004; Salmon & Angood, 2013). Others go further, proposing a new concept of ‘Digital Education Leadership’ to mark the shift in focus from emphasising leadership in educational technology to “the fostering of leaders who have the qualities to lead in a digital culture” (Brown et al., 2016, p. 8) where “Digital education leadership is concerned with providing direction in terms of digital education by enhancing access, capacitating peers, making informed decisions and cultivating innovation, to achieve the learning goal (digital literacy).” (Brown et al., 2016, p. 10). However, as can be expected with the introduction of a new concept, a search in the three main databases (ISI Web of Science, Scopus and ERIC) for peer-reviewed papers using the search terms “Digital Education Leadership” AND “Higher Education” produced no results. This would thus not have been useful for our literature review at this stage, but should be included in future searches alongside the combinations already used.

Trends

Looking back at some of the major themes emerging from Jameson’s 2013 study, we can see that the majority are still prevalent, to differing degrees. Comparisons of transformational versus transactional leadership are still present (3 results) although there is a clear development of studies focusing on distributed or shared leadership, with 26% of the empirical studies and 38% of the theoretical analyses referring to this concept.

Figure 6 below shows the number and distribution of occurrences of the main themes from Jameson’s e-leadership framework, where these themes were present in 5 or more results.

Thematic analysis of results 2013-2017 compared to Jameson’s (2013) e-Leadership framework

Jameson’s framework (Fig. 2) is structured around three major dimensions: Purpose, People and Structures & Social Systems. In the “Purpose” dimension, e-Leadership visioning, Strategic planning and Learning & Teaching are the three most cited themes among the results in this 2013-2017 study. For the “People” dimension, we find Collaboration and collegiality; Values, behaviour and culture; Interpersonal skills; Training and Continuous Professional Development (CPD). Finally, for the “Structures & Social Systems” dimension, the three most cited themes are Distributed leadership, Change management and Resource allocation.

Other emerging themes, over and above those covered in Jameson’s framework, are identified as:

-

the application of technology acceptance and adoption models (Akcil et al., 2017; Boyd & Sampson, 2016; King & Boyatt, 2015; Livingstone, 2015; Markova, 2014; Sutton & DeSantis, 2017; Van Wart et al., 2017);

-

the application of tools and methods from the business world, as suggested by Sangrà (2009), with the caveat of the necessary cultural adaptation to HE (Chow, 2013; Mishra et al., 2016; Spackman et al., 2015; Tay & Low, 2017);

-

using data for decision-making (Brown et al., 2016; Burnette, 2015; Persichitte, 2013);

-

studying TEL adoption from the point of view of organisational learning (Tintoré & Arbós, 2013; Trevitt et al., 2017);

-

personal digital competence / literacy / confidence, of both leaders and staff (Akcil et al., 2017; Boyd & Sampson, 2016; Brown et al., 2016; Domingo-Coscollola et al., 2016).

Recommendations

This paper identifies four main gaps in the current research. These can be expressed in terms of populations studied, methodologies used, the disciplines to which these studies are related and the application of models and frameworks.

The first gap is defined as a lack of research at a holistic level, linking leadership to strategy and organisation. As Alvesson (2017) states: “Leadership is not a simple original source of much influencing, but needs to be placed in a broader context of hierarchical and vertical divisions of work, labour processes and cultural and material pressures from various interest groups” (Alvessson, 2017, p. 12). If we are looking to support HE leaders in developing strategic thinking, vision and action to improve the way technology is used for teaching and learning, then the focus of research needs to go beyond the analysis of leadership at project level, with more empirical studies addressing the question of leadership for TEL from a holistic, multi-stakeholder perspective at institutional level. The six results identified in this literature review would benefit from comparison with further studies taking such an approach to build up a much more comprehensive literature base.

Bridging the second gap involves employing robust research designs to take into account the complexity of such a holistic approach. Mixed Methods Research is particularly relevant for this as it “offers richer insights into the phenomenon being studied and allows the capture of information that might be missed by utilizing only one research design, enhances the body of knowledge, and generates more questions of interest for future studies that can handle a wider range of research questions.” (Caruth, 2013). Furthermore, given the complex nature of leadership research, mixed methods enable the scholar to provide the most complete analysis, “extending beyond mere quantitative numbers or qualitative words” (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Stentz, Plano Clark, & Matkin, 2012). Such an approach should also contribute to reducing researcher bias and avoid the limitation which Roushan et al. (2016) identify in their study, in that the researchers being themselves advocates of TEL may have meant that some opposition to change was under-reported.

The third gap concerns a distinct lack of interdisciplinary research. Given that this research takes place at the intersection of different disciplinary fields - education technology and management studies - insights from both fields are required. It is thus recommended that interdisciplinary teams collaborate on such research in order to reinforce synergies and ensure the best possible understanding of both worlds. In this respect, much can be learnt from the HE leadership and management literature, for example H. Davis’ work on Leadership Literacies (Davis, 2012, 2014; Davis & Jones, 2014), and by continuing to develop the connections between leadership and change management for TEL (Martins & Baptista Nunes, 2016; Risquez & Moore, 2013). Further efforts to publish in education management journals should also be made, in order to increase the awareness of issues relating to the integration of technology for teaching and learning at HE governance level.

The final gap concerns the need to test existing models and frameworks through application in empirical studies. As we have seen, a number of models have been developed, either through empirical or theoretical studies (Díaz & Báez, 2015; Jameson, 2013; Khanna, 2017; Markova, 2014; McCutcheon, 2014). It would thus appear timely to test the validity of these frameworks in the field, through case studies focusing on qualitative contextual data as well as quantitative analysis.

Specific research lines should thus be fostered at meso (institutional) level, focusing on values, strategy, organisation and leadership interactions, while at the same time taking into account macro factors such as the economy and public policy, as well as teaching and learning at the micro level. Attention should be paid to making explicit any underlying assumptions about TEL, on the part of both the researchers themselves and the populations being studied (Bayne, 2015). A further focus should be placed on studying leadership development with specific reference to TEL, exploring the learning ecologies (Esposito, Sangrà, & Maina, 2015) of HE leaders who are making decisions about technology for teaching and learning. In other words, what formal and informal learning do they engage in and what influences their world views with respect to the changing technology landscape and its impact on teaching and learning? Related to this, studies could focus specifically on the relationships between HE leaders’ own (critical) digital literacies (Belshaw, 2014), their awareness of the affordances of technology for teaching and learning, and their leadership attitudes and behaviour with respect to TEL.

Conclusion

Given the relative paucity of empirical results in this update of Jameson’s 2013 literature review, at a time when HE leaders still need to develop their capacity for strategic thinking with respect to the integration of technology for learning and teaching, we conclude that further research into (e-)leadership for TEL in higher education would be welcome, just as Jameson herself did. The question of how we define e-leadership also needs to be addressed. Rather than hide behind arguments of conceptual ambiguity, it would be preferable for scholars in the field to draw on emerging proposals for including decision-making for TEL adoption at organisational level in the definition or to place e-leadership firmly within the original scope of leading in virtual environments and to adopt another concept such as that of “Digital Education Leadership”.

There are of course limitations to this study in that it is intended as an update to that carried out by Jameson and thus covers a relatively short period (2013-2017). Further regular searches will be carried out, including citation analysis.

Finally, we argue for more collaboration between the disciplinary fields of educational technology and educational management. The sun may not yet have fully dawned on e-leadership as the 5th age of educational technology research in higher education, but there is both the potential and the need for this age to emerge at the intersection of these disciplines.

Abbreviations

- AIT:

-

Advanced information technology

- CIO:

-

Chief Information officer

- CPD:

-

Continuous professional development

- ES:

-

Empirical studies

- FRLT:

-

Full range leadership theory

- HE:

-

Higher education

- ICT:

-

Information and communication technology

- IT:

-

Information technology

- MMR:

-

Mixed methods research

- NHS:

-

National health system (UK)

- ODL:

-

Open and distance learning

- OP:

-

Opinion pieces

- QUAL:

-

Qualitative research

- QUAN:

-

Quantitative research

- TA:

-

Theoretical analyses

- TEL:

-

Technology-enhanced learning

- TPACK:

-

Technological, pedagogical and content knowledge

References

Akcil, U., Aksal, F. A., Mukhametzyanova, F. S. M., & Gazi, Z. A. G. (2017). An Examination of Open and Technology Leadership in Managerial Practices of Education System. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 13(1), 119–131 https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00607a.

Alvesson, M. (2017). Waiting for Godot: Eight major problems in the odd field of leadership studies. Leadership, 174271501773670. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715017736707

Arena, M. J., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2016). Complexity Leadership Theory : Shifting from Human Capital to Social Capital. People and Strategy, 39(2), 22–27.

Ashbaugh, M. L. (2013). Expert Instructional Designer Voices: Leadership Competencies Critical to Global Practice and Quality Online Learning Designs. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 14(2), 97–118.

Avolio, B. J., Kahai, S., & Dodge, G. E. (2001). E-Leadership : Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 615–668.

Avolio, B. J., Sosik, J. J., Kahai, S. S., & Baker, B. (2014). E-leadership: Re-examining transformations in leadership source and transmission. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 105–131.

Barber, M., Donnelly, K., & Rizvi, S. (2013). An Avalanche is Coming: Higher Education and the Revolution Ahead. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1997). Full range leadership development: Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Mind Garden.

Bälter, O. (2017). Moving Technology-Enhanced-Learning Forward: Bridging Divides through Leadership. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18 (3).

Bates, A. W. Tony. (2015). Teaching in a Digital Age. Retrieved January 8, 2017, from http://www.tonybates.ca/teaching-in-a-digital-age

Bates, A. W. T., & Sangrà, A. (2011). Managing technology in higher education: Strategies for transforming teaching and learning. Hoboken: Wiley.

Baydas, O., Kucuk, S., Yilmaz, R. M., Aydemir, M., & Goktas, Y. (2015). Educational technology research trends from 2002 to 2014. Scientometrics, 105(1), 709–725.

Bayne, S. (2015). What’s the matter with “technology-enhanced learning”? Learning. Media and Technology, 40(1), 5–20 https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.915851.

Beaudoin, M. (2002). Distance Education Leadership: An Essential Role For The New Century. Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(3), 131–144 https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200800311.

Beaudoin, M. (2016). Issues in Distance Education: A Primer for Higher Education Decision Makers. New Directions for Higher Education, 173, 9–19 https://doi.org/10.1002/he.

Belshaw, D. (2014). The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2.

Bervell, B., & Umar, I. N. (2017). A Decade of LMS Acceptance and Adoption Research in Sub-Sahara African Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Models, Methodologies, Milestones and Main Challenges. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(11), 7269–7286.

Bogler, R., Caspi, A., & Roccas, S. (2013). Transformational and Passive Leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(3), 372–392 https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143212474805.

Bolden, R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: A review of theory and research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(3), 251–269 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x.

Bolden, R., Gosling, J., & Petrov, G. (2009). Distributed leadership in higher education: Rhetoric and reality. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 37(2), 257–277.

Boyd, V., & Sampson, A. (2016). Foundation versus innovation: developing creative education practitioner confidence in the complex blended learning landscape. Professional Development in Education, 42(3), 502–506 https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2015.1024800.

Boyer, A. (2016). Guidelines for governance of HE institutions, D-Transform. Retrieved January 13, 2017, from http://www.dtransform.eu/resources/#O1-A4

Brown, C., Czerniewicz, L., Huang, C.-W., & Mayisela, T. (2016). Curriculum for Digital Education Leadership: A Concept Paper. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/2442

Brown, M. (2014). Reenvisioning Teaching and Learning: Opportunities for Campus IT. Libraries and the Academy, 14(3), 383–391.

Brown, S. (2013). Large-scale innovation and change in UK higher education. Research in Learning Technology, 21, 1–14 https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21i0.22316.

Burnette, D. (2015). Negotiating the mine field: Strategies for effective online education administrative leadership in higher education institutions. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(3), 13–35.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Caruth, G. D. (2013). Demystifying Mixed Methods Research Design: A Review of the Literature. Mevlana International Journal of Education (MIJE), 3(2), 112–122.

Chow, A. S. (2013). One Educational Technology Colleague’s Journey from Dotcom Leadership to University E-Learning Systems Leadership: Merging Design Principles, Systemic Change and Leadership Thinking. TechTrends, 57(5), 64–75 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-013-0693-6.

Ciabocchi, E., Ginsberg, A. P., & Picciano, A. G. (2016). A Study of Faculty Governance Leaders’ Perceptions of Online and Blended Learning. Online Learning, 20(3), 52–73.

Cifuentes, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2015). ICT Leadership in Higher Education : A Multiple Case Study in Colombia. Media Education Research Journal, 23, 133–141.

Clarke, N. (2013). Model of complexity leadership development. Human Resource Development International, 16(2), 135–150.

Craig, R. (2015). College disrupted: The great unbundling of higher education. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

D’Emidio, T., Dorton, D., & Duncan, E. (2015). Service innovation in a digital world. McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved from http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/service-innovation-in-a-digital-world

Davis, F. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease Of Use, And User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319 https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

Davis, H. (2012). Leadership Literacies for Professional Staff in Universities. (Doctoral thesis). Retrieved from https://researchbank.rmit.edu.au/view/rmit:160335.

Davis, H. (2014). Towards leadingful leadership literacies for higher education management. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(4), 371–382.

Davis, H., & Jones, S. (2014). The work of leadership in higher education management. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(4), 367–370 https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.916463.

Davis, N., & Higgins, A. (2015). Researching Possible Futures to Guide Leaders Towards More Effective Tertiary Education. Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning, 19(2), 8–24.

Díaz, Y., & Báez, L. (2015). Exploración de la capacidad de liderazgo para la incorporación de TICC en educación: validación de un instrumento. RELATEC - Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa, 14(3), 35–47 https://doi.org/10.17398/1695.

Domingo-Coscollola, M., Arrazola-Carballo, J., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2016). Do It Yourself in Education : Leadership for Learning across Physical and Virtual Borders. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 4(1), 5–29 https://doi.org/10.17583/ijelm.2016.1842.

Esposito, A., Sangrà, A., & Maina, M. (2015). Emerging learning ecologies as a new challenge and essence for e-learning. The case of doctoral e-researchers. International Handbook of E-Learning, 1, 331–342 https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315760933.

Garrison, R., & Vaughan, N. (2013). Institutional change and leadership associated with blended learning innovation: Two case studies. The Internet and Higher Education, 18, 24–28.

Gibb, C. A. (1954). Leadership. In G. Lindzey (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology, Vol 2 (pp. 877–917). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 423–451 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00120-0.

Gronn, P. (2008). The future of distributed leadership. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(2), 141–158 https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810863235.

Gupton, S. L. (2014). Online Frontiers in Education : Leadership’s Role. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 7(2), 609–616.

Gurr, D. (2004). ICT, Leadership in Education and E-leadership. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 25(1), 113–124.

Harris, A. (2008). Distributed leadership: according to the evidence. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(2), 172–188 https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810863253.

Harris, A., & Spillane, J. (2008). Distributed leadership through the looking glass. Management in Education, 22(1), 31–34 https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020607085623.

Hazy, J. K., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2015). Towards operationalizing complexity leadership: How generative, administrative and community-building leadership practices enact organizational outcomes. Leadership, 11(1), 79–104.

Holt, D., Palmer, S., Gosper, M., Sankey, M., & Allan, G. (2015). Framing and enhancing distributed leadership in the quality management of online learning environments in higher education. Distance Education, 35(3), 382–399.

Hughes, J., Thomas, R., & Scharber, C. (2006). Assessing Technology Integration: The RAT – Replacement, Amplification, and Transformation - Framework. In C. Crawford, R. Carlsen, K. McFerrin, J. Price, R. Weber, & D. Willis (Eds.), Proceedings of SITE 2006-, USA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Inayatullah, S., & Milojevic, I. (2014). Augmented reality, the Murabbi and the democratization of higher education: alternative futures of higher education in. On the Horizon, 22(2), 110–126 https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-08-2013-0029.

Jameson, J. (2013). E-Leadership in higher education: The fifth “age” of educational technology research. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(6), 889–915.

Keeble, H., & Kirk, R. (2007). Exploring the existing body of research. In A. Briggs & M. Coleman (Eds.), Research Methods in Educational Leadership and Management. Sage Thousand Oaks, CA.

Khanna, P. (2017). A conceptual framework for achieving good governance at open and distance learning institutions. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 32(1), 21–35 https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2016.1246246.

King, E., & Boyatt, R. (2015). Exploring factors that influence adoption of e-learning within higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(6), 1272–1280 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12195.

Livingstone, K. A. (2015). Administration’s perception about the feasibility of elearning practices at the University of Guyana. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 11(2), 65–84.

Lucas Jr., H. C. (2016). Technology and the Disruption of Higher Education. Singapore: World Scientific.

Markova, M. (2014). A Model of Leadership in Integrating Educational Technology in Higher Education. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 17, 4.

Martins, J. T., & Baptista Nunes, M. (2016). Academics’ e-learning adoption in higher education institutions: a matter of trust. The Learning Organization, 23(5), 299–331.

McCutcheon, K. (2014). A Leadership Framework to Support the use of E-Learning Resources. Nursing Management, 21(3), 24–28.

Mishra, P., Henriksen, D., Boltz, L. O., & Richardson, C. (2016). E-Leadership and Teacher Development using ICT. In R. Huang & J. K. Price (Eds.), ICT in Education in Global Context (pp. 248–266). Berlin, Heidelberg, DE: Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-43927-2

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x.

Moccia, S. (2016). Managing Educational Reforms during Times of Transition: The Role of Leadership. Higher Education for the Future, 3(1), 26–37 https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631115611278.

Moreau, F. (2013). The Disruptive Nature of Digitization: The Case of the Recorded Music Industry. International Journal of Arts Management, 15(2), 18–31.

Mukerjee, S. (2014). Agility : a crucial capability for universities in times of disruptive change and innovation. Australian Universities Review, 56(1), 56–60.

Murphy, T. (2016). The future of Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) is in the hands of the anonymous, grey non-descript mid-level professional manager. Irish Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 2(1), 1–9 https://doi.org/10.22554/ijtel.v2i1.14.

Ng’ambi, D., & Bozalek, V. (2013). Leveraging informal leadership in higher education institutions: A case of diffusion of emerging technologies in a southern context. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(6), 940–950 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12108.

Öchsner, A. (2013). Types of Scientific Publications. In A. Öchsner (Ed.), Introduction to Scientific Publishing. SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology, (pp. 9–21). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38646-6_3.

Orr, T., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2015). Appreciative leadership: Supporting education innovation. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(4), 235–241.

Persichitte, K. A. (2013). Leadership for Educational Technology Contexts in Tumultuous Higher Education Seas. TechTrends, 57(5), 14–17 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-013-0686-5.

Phelps, K. C. (2014). “So much technology, so little talent”? Skills for harnessing technology for leadership outcomes. Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(2), 51–56 https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.

Preston, J. P., Moffatt, L., Wiebe, S., McAuley, A., Campbell, B., & Gabriel, M. (2015). The use of technology in Prince Edward Island (Canada) high schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(6), 989–1005 https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214535747.

Pretto, G., & Curró, G. (2017). An Approach for Doctoral Students Conducting Context-Specific Review of Literature in IT, ICT, and Educational Technology. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 23(1), 60–83 https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2016.1227861.

Risquez, A., & Moore, S. (2013). Exploring feelings about technology integration in higher education. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26(2), 326–339.

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. New York, NY: Glencoe Free Press.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations, (5th ed., ). New York: Free Press.

Rogers, E. M., & Scott, K. L. (1997). The Diffusion of Innovations Model and Outreach from the National Network of Libraries of Medicine to Native American Communities. Retrieved November 25, 2017, from https://nnlm.gov/archive/pnr/eval/rogers.html

Rogers, J. (2013). The death and life of the music industry in the digital age. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Roushan, G., Holley, D., & Biggins, D. (2016). The Kaleidoscope of Voices: An Action Research Approach to Informing Institutional e-Learning Policy. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 14(5), 293–300.

Salmon, G., & Angood, R. (2013). Sleeping with the enemy. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(6), 916–925 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12097.

Sangrà, A. (2009). La integració de les TIC a la universitat: models, problemes i reptes. (Doctoral thesis). Retrieved from http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/8947.

Selwyn, N. (2013). Discourses of digital “disruption” in education : a critical analysis. In Fifth International Roundtable on Discourse Analysis, City University Hong Kong, May 23-25, 2013, (pp. 1–28).

Sheiladevi, S., & Rahman, A. (2016). An Investigation on Impact of E-Learning Implementation on Change Management in Malaysian Private Higher Education Institutions. Pertanika Jouornal of Science and Technology, 24(2), 517–530.

Shirky, C. (2012). Napster, Udacity, and the academy. Retrieved January 8, 2017, from http://www.shirky.com/weblog/2012/11/napster-udacity-and-the-academy/.

Singh, G., & Hardaker, G. (2017). Teaching in Higher Education Change levers for unifying top-down and bottom- up approaches to the adoption and diffusion of e- learning in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(6), 736–748 https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1289508.

Spackman, J. S., Thorup, J., & Howell, S. L. (2015). What Can the Business World Teach Us About Strategic Planning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 18, 2.

Spillane, J. P. (2012). Distributed leadership, (vol. 4). San Francisco: Wiley.

Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2004). Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies (Vol. 36). https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000106726.

Staley, D. J., & Trinkle, D. A. (2011). The changing landscape of higher education. Educause Review, 46(1), 16–32.

Stentz, J. E., Plano Clark, V. L., & Matkin, G. S. (2012). Applying mixed methods to leadership research: A review of current practices. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(6), 1173–1183.

Stewart, J. (2006). Transformational leadership: An evolving concept examined through the works of Burn, Bass, Avolio and Leithwood. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 54(54), 1–29.

Stoddart, P. (2015). Using educational technology as an institutional teaching and learning improvement strategy? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(5), 586–596.

Sutton, K. K., & DeSantis, J. (2017). Beyond change blindness: embracing the technology revolution in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(3), 223–228 https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1174592.

Suzor, N., & Wikstrom, P. (2016). Paper 1: The disruptive forces of the sharing economy. The Innovation Paper, 1–5.

Tay, H. L., & Low, S. W. K. (2017). Digitalization of learning resources in a HEI – a lean management perspective. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 66(5), 680–694.

Tian, M., Risku, M., & Collin, K. (2016). A meta-analysis of distributed leadership from 2002 to 2013. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 44(1), 146–164 https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214558576.

Tintoré, M., & Arbós, A. (2013). Identifying the stage of growth in the organisational learning capacity of universities. Universities and Knowledge Society Journal (RUSC), 10. No, 2(2013), 375–393.

Trevitt, C., Steed, A., Du Moulin, L., & Foley, T. (2017). Leading entrepreneurial e-learning development in legal education: A longitudinal case study of “universities as learning organisations.”. The Learning Organization, 24(5), 298–311.

Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., & McKelvey, B. (2007). Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(4), 298–318.

Van Wart, M., Roman, A., Wang, X. H., & Liu, C. (2017). Integrating ICT adoption issues into (e-)leadership theory. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 527–537 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.11.003.

Watson, W. R., & Watson, S. L. (2013). Exploding the Ivory Tower: Systemic Change for Higher Education. Tech Trends, 57(5), 42–46 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-013-0690-9.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26(2), xiii–xxiii. https://doi.org/10.2307/4132319.

Weller, M., & Anderson, T. (2013). Digital Resilience in Higher Education. European Journal of Open, Distance & E-Learning, 16(1), 53–66.

Wheeler, S. (2012). e-Learning and digital learning. In Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning, (pp. 1109–1111). Berlin: Springer.

Winn, W. (2002). Current trends in educational technology research: The study of learning environments. Educational Psychology Review, 14(3), 331–351.

Zawacki-Richter, O., & Naidu, S. (2016). Mapping research trends from 35 years of publications in Distance Education. Distance Education, 37(3), 245–269.

Zhu, C. (2015). Organisational culture and technology-enhanced innovation in higher education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(1), 65–79 https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.822414.

Zhu, C., & Engels, N. (2014). Organizational culture and instructional innovations in higher education. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(1), 136–158 https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213499253.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This is a fully co-authored paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

DA is a PhD student on the Education & ICT doctoral programme at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

AS is director of the UNESCO Chair in Education & Technology for Social Change and associate professor

at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Arnold, D., Sangrà, A. Dawn or dusk of the 5th age of research in educational technology? A literature review on (e-)leadership for technology-enhanced learning in higher education (2013-2017). Int J Educ Technol High Educ 15, 24 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0104-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0104-3