Abstract

Background

The Bahamas is a region with high diversity of marine molluscs and a high rate of endemism. In certain groups of heterobranchs it is common to observe a distribution pattern consisting of an endemic species from the Bahamas, sister to a widespread western Atlantic species living in the same kind of habitat. This would suggest an allopatric speciation process and lack of gene flow between the Bahamian and the Caribbean subprovinces. However, the Bahamian aeolidacean mollusc Spurilla dupontae is sister to an eastern Atlantic congener.

Results and Conclusions

In this paper, S. dupontae, to date considered endemic to the Bahamas, is recorded for the first time in the Caribbean subprovince (Martinique).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Bahamian Archipelago is a region with high diversity of marine molluscs (Redfern 2001; Redfern 2013). It is considered a distinct biogeographic subprovince referring to molluscs (within the Caribbean province), with high levels of micro-speciation and endemism because of the disjunct arrangement of separate malacofaunas in the over 8000 islands and coral cays that compose it (Petuch 2013). The micro-speciation phenomenon is particularly evident in groups with non-planktotrophic development (Ornelas-Gatdula et al. 2011; Ornelas-Gatdula and Valdés 2012), especially when studied as a whole in the area (Caballer et al. 2014). The high rate of endemism observed may be the result of the isolation, caused by extensive open areas of “sterile” sands, which act as ecological barriers (Petuch 2013), or it may be explained by post-recruitment ecological factors, or historic vicariance (Ornelas-Gatdula and Valdés 2012; Carmona et al. 2014).

Ornelas-Gatdula and Valdés (2012) and Malaquias (2014) published a brief overview on the biogeography of the Bahamas and on the connectivity between the diverse regions of the Caribbean. These authors pointed out the existence of genetically distinct clades in this subprovince for some groups of molluscs, despite the general faunal homogeneity of the Caribbean. Moreover, Malaquias (2014) remarked the importance of the Bahamas for the biodiversity of the whole tropical western Atlantic region and discussed that the archipelago may “act as a centre of origination of new species”. In addition, it seems common in certain families of heterobranchs to observe a distribution pattern comprising an endemic species from the Bahamas that is sister to a widespread western Atlantic species living in the same kind of habitat, suggesting an allopatric speciation process (Carmona et al. 2014).

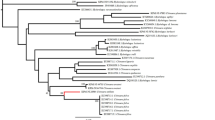

Spurilla dupontae Carmona, Lei, Pola, Gosliner, Valdés & Cervera, (2014) is a species of aeolidacean mollusc described as being endemic to the Bahamas. In the latest morphological and molecular phylogeny of the genus provided by Carmona et al. (2014), it was found to be a sister taxa to a species from the eastern Atlantic (also see Carmona et al. 2013), whose taxonomical identity has been discussed by Ortea and Caballer (2014). The abnormal speciation pattern of both species led Carmona et al. (2014) to suggest that there is no universal explanation for the origin of the endemic heterobranch fauna of the Bahamas.

In this paper, S. dupontae, to date considered endemic to the Bahamas, is recorded for the first time in the Caribbean subprovince.

Methods

The only specimen of S. dupontae was collected by direct search during a scuba dive. It was photographed alive on its environment, then examined onshore, photographed in an aquarium and preserved in 98 % ethanol.

Results

Systematics

Order Nudibranchia Cuvier, 1817

Family Aeolidiidae Gray, 1827

Genus Spurilla Bergh (1864)

Spurilla dupontae Carmona, Lei, Pola, Gosliner, Valdés & Cervera, 2014 (Fig. 1)

Spurilla dupontae Carmona et al. 2014, Bay of Fort-de-France, Martinique: a dorsal view; b left side view

Material examined

Bay of Fort-de-France, Martinique, 1 specimen, 21 mm long alive, collected on Halophila spp., 3 m depth, 20 November 2013.

Description

Body elongate, tapering abruptly to the posterior end, translucent white to yellowish-brown, with an ochre to brownish-green reticulate pattern and white spots all over the dorsum and cerata (Fig. 1). Rhinophores, oral tentacles and foot corners bearing the same reticulate pattern as the rest of the body. Anterior foot corners tentaculiform. Rhinophores perfoliate, with a white apex, bearing 9–12 lamellae. Oral tentacles long and slender. Cerata cylindrical, curved inwards, shorter than the rhinophores, arranged in five arches from behind the rhinophores to the posterior end. Each arch contains between three and seven cerata, decreasing in size towards the foot. Anus within the second right arch. Gonopore among the cerata of the group on the right.

Discussion and conclusion

Carmona et al. (2014) studied the genus Spurilla Bergh, 1864 in depth, and concluded “that coloration is one of the main diagnostic traits for the five species” of the genus, “although some display substantial colour pattern variation”. These authors also established the distribution of the western Atlantic species: S. dupontae and Spurilla sargassicola Bergh, 1871 inhabit the Bahamas, and Spurilla braziliana MacFarland, 1909, the only representative of Spurilla in the Caribbean.

Carmona et al. (2014) observed "an intriguing combination of widespread species and endemics with restricted ranges" for the members of the genus Spurilla, while some recent papers on heterobranch sea slugs published by Ornelas-Gatdula et al. (2011), Ornelas-Gatdula and Valdés (2012), Carmona et al. (2013), proved the presence of some new cryptic species in the Bahamas not known in the Caribbean subprovince. In this context, it seemed logical to assume that S. dupontae was endemic to the Bahamas, as Carmona et al. (2014: 150) did. But the specimen of S. dupontae found in Martinique matches exactly on the original description of the species, and it is easy to distinguish from S. braziliana and S. sargassicola by the conspicuous reticulate pattern covering the body, and specially the rhinophores.

Since its original description, there has not been any records to S. dupontae in the Caribbean or anywhere else, but S. sargassicola, which shows certain similarities with S. dupontae, has been cited by Caballer et al. (2015) in Venezuela. This specimen from the southern end of the Caribbean, was collected on Caulerpa spp. and the illustration provided by Caballer et al. (2015: 5 E) shows an animal with a reticulate pattern that seem to include the rhinophores, thus, this record could be, indeed, attributed to S. dupontae. On the other hand, the Guadeloupe Archipelago is very close to Martinique, and nearer to the Bahamas. However, S. dupontae has not been captured there, not even after the intensive expeditions performed by the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (Paris) in 2012, which permitted a wide study of the sea slug fauna from the Archipelago (Ortea et al. 2012; Ortea et al. 2013; Caballer and Ortea 2014; Caballer and Ortea 2015) and the capture its congener S. braziliana (as S. neapolitana).

It has been stated that the Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands are a special region in the western Atlantic, largely isolated from the Caribbean, except for minor exchange from the north coast of Cuba and Haiti (Cowen et al. 2006). The presence of S. dupontae in the Caribbean subprovince (even when scarce), implies that planktotrophy is the most probable way of development for this species, and suggests that there may be more gene flow between the Bahamas and the Lesser Antilles than that predicted by the model owed to Galindo et al. (2006).

In synthesis, further collections of S. dupontae are necessary to learn its real distribution in the Caribbean Province and to determine if its presence in Martinique is incidental or if the species is really established in the Island.

References

Bergh R. Anatomiske bidrag til kundskab om Aeolidierne. Det Kongelige Videnskabernes Selskabs Skrifter, Naturvidenskabelige og Mathematiske Afdeling. 1864;7:139–316.

Bergh R. Beiträge zur kenntniss der Mollusken des Sargassomeeres. Verhandlungen der königlich–kaiserlich Zoologisch–botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien (Abhandlungen). 1871;21:1273–308.

Caballer M, Ortea J. A new sibling species of Notobryon Odhner, 1936 (Gastropoda, Nudibranchia) from the Caribbean Sea. J Mar Biol Assoc U K. 2014;94:1465–70.

Caballer M, Ortea J. The first species of Spiniphiline Gosliner, 1988 (Gastropoda: Cephalaspidea) in the Atlantic Ocean, with notes on its systematic position. J Molluscan Stud. 2015;82(1):122–8. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyv041.

Caballer M, Ortea J, Redfern C. On the genus Rissoella Gray, 1847 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Heterobranchia) in the Bahamas. Am Malacol Bull. 2014;32(1):104–21.

Caballer M, Ortea J, Rivero N, Carias G, Malaquias MAE, Narciso S. The opisthobranch gastropods (Mollusca: Heterobranchia) from Venezuela: an annotated and illustrated inventory of species. Zootaxa. 2015;4034:201–56.

Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera L. A tale that morphology fails to tell: a molecular phylogeny of Aeolidiidae (Aeolidida, Nudibranchia, Gastropoda). PloS ONE. 2013;8, e63000. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063000.

Carmona L, Lei BR, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Valdés Á, Cervera JL. Untangling the Spurilla neapolitana (Delle Chiaje, 1841) species complex: a review of the genus Spurilla Bergh, 1864 (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Zool J Linnean Soc. 2014;170(1):132–54.

Cowen RK, Paris CB, Srinivasan A. Scaling of connectivity in marine populations. Science. 2006;311:522–7.

Cuvier GL. Le regne animal distribué d’après son organisation, tome 2 contenant les reptiles, les poissons, les mollusques, les annélides. Paris: Deterville; 1817.

Galindo HM, Olson DB, Palumbi SR. Seascape genetics: a coupled oceanographic-genetic model predicts population structure of Caribbean corals. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1622–6.

Gray JE. Plate Mollusca (= plate 3), plate Mollusca III (= plate 4), plate Mollusca IV (= plate 6). In: Smedley E, Rose HJ, editors. Encyclopaedia Metropolitana, vol. 7. London: Smedley, E; 1827.

MacFarland FM. The opisthobranchiate Mollusca of the Branner-Agassiz expedition to Brazil. In: MacFarland FM, editor. University series (2). Stanford: Leland Stanford Junior University Publications; 1909. p. 1–104. pls. 1–19.

Malaquias AEM. New data on the heterobranch gastropods (‘opisthobranchs’) for the Bahamas (tropical western Atlantic Ocean). Marine Biodiversity Records. 2014;7, e27.

Ornelas-Gatdula E, Valdés Á. Two cryptic and sympatric species of Philinopsis (Cephalaspidea: Aglajidae) in the Bahamas distinguished using molecular and anatomical data. J Molluscan Stud. 2012;78:313–20.

Ornelas-Gatdula E, DuPont A, Valdés Á. The tail tells the tale: taxonomy and biogeography of some Atlantic Chelidonura (Gastropoda: Cephalaspidea: Aglajidae) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial gene data. Zool J Linnean Soc. 2011;163:1077–95.

Ortea J, Caballer M. Notes in Opisthobranchia (Mollusca, Gastropoda) 8. On the interpretation of the Code and the synonymies of Spurilla onubensis Carmona, Lei, Pola, Gosliner, Valdés & Cervera, 2014 and Berghia dakariensis Pruvot-Fol, 1953 (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidida). Revista de la Academia Canaria de Ciencias. 2014;26:293–7.

Ortea J, Espinosa J, Caballer M, Buske Y. Initial inventory of the sea slugs (Opisthobranchia and Sacoglossa) from the expedition KARUBENTHOS, held in May 2012 in Guadaloupe (Lesser Antilles, Caribbean Sea). Revista de la Academia Canaria de Ciencias. 2012;24:153–82.

Ortea J, Espinosa J, Buske Y, Caballer M. Additions to the inventory of the sea slugs (Opisthobranchia and Sacoglossa) from Guadeloupe (Lesser Antilles, Caribbean Sea). Revista de la Academia Canaria de Ciencias. 2013;25:163–94.

Petuch EJ. Biogeography and biodiversity of Western Atlantic mollusks. Florida: CRC Press; 2013.

Redfern C. Bahamian seashells, A thousand species from Abaco, Bahamas. Boca Raton: Bahamianseashells.com, Inc; 2001.

Redfern C. Bahamian seashells, 1161 species from Abaco, Bahamas. Boca Raton: Bahamianseashells.com, Inc; 2013.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jesus Ortea (University of Oviedo) for his constructive comments. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declares that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YB collected and fixed the specimen, registered complementary data and took photos of the living animal. MC studied the anatomy of the specimen once preserved, revised the pertinent scientific literature and drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Caballer, M., Buske, Y. First record of the Bahamian mollusc Spurilla dupontae (Mollusca: Aeolidiidae) in the Caribbean subprovince. Mar Biodivers Rec 9, 20 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0021-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0021-x