Abstract

Background

Although there is a wide use of wild edible plants (WEPs) in Ethiopia, very little work has so far been done, particularly, in the Tigray Region, northern Ethiopia, to properly document the associated knowledge. The purpose of this study was, therefore, to document knowledge and analyze data related to the use of wild edible and nutraceutical plants in Raya-Azebo District of Tigray Region. The district was prioritized for the study to avoid the further loss of local knowledge and discontinuation of the associated practices because of the depletion of wild edible plants in the area mainly due to agricultural expansion and largely by private investors.

Methods

A cross-sectional ethnobotanical study was carried out in the study District to collect data through individual interviews held with purposively selected informants, observation, market surveys, and ranking exercises. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were employed to analyze and summarize the data using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.

Results

The study documented 59 WEPs, the majority of which (57.63%) were sought for their fruits. Most of the WEPs (49 species) were consumed in the autumn, locally called qewei, which includes the months of September, October, and November. Ziziphus spina-christi L. Desf., Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. and Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller were the most preferred WEPs. Both interviews and local market surveys revealed the marketability of Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Ficus vasta Forssk., Ficus sur Forssk., and Balanites aegyptiaca. Of the total WEPs, 21 were reported to have medicinal (nutraceutical) values, of which Balanites aegyptiaca and Acacia etbaica scored the highest rank order priority (ROP) values for their uses to treat anthrax and skin infections, respectively.

Conclusions

The current investigation demonstrated the wide use of WEPs in the district. In future nutritional composition analysis studies, priority should be given to the most popular WEPs, and nutraceutical plants with the highest ROP values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wild edible plants (WEPs) play an important role in the livelihood of many rural communities across the world, particularly, in providing reliable alternatives when the production of cultivated crops decreases or fails [1,2,3,4,5]. Wild edible plants serve as source of vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, fibers and minerals and are particularly rich in vitamins A and C, zinc, iron, calcium, iodine, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and folacin. Moreover, WEPs are valuable for the development of new food crops through domestication and in serving as a genetic resource pool needed to improve the productivity of cultivars [5, 6]. They provide a good source of cash income for local communities in different parts of the world [7,8,9]. There is also a long history of use of WEPs by communities in different parts of the world as medicines (nutraceuticals) to manage various ailments [10, 11], and reports show that such plants are still serving as an important source of medicines in the prevention and treatment of diseases [12, 13].

There is a wide use of WEPs in Ethiopia as supplement foods as revealed by different ethnobotanical studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, studies show the utilization of WEPs in the country as nutraceuticals [25,26,27]. However, very little work that covered very limited geographical area has so far been done in Tigray Region, northern Ethiopia, to document local knowledge related to the use of WEPs [28,29,30,31]. A study conducted in Indaselassie-Shire District (North Western Tigray Zone) documented eight wild and semi-wild edible plants [29]. A survey carried out in Laelay Maichew and Tahtay Maichew districts (Central Tigray Zone) reported the use of three WEPs [28]. A study conducted in Raya-Alamata district (Southern Tigray Zone) revealed the use of 37 wild and semi-wild edible plants [30]. Another study carried out in Kilte Awlaelo district (Eastern Tigray Zone) recorded the use of 30 wild and semi-wild edible plants [31]. To the knowledge of the authors, there is no report of previous conduct of ethnobotanical study in Raya-Azebo district that aimed at documenting the use of WEPs. The purpose of this study was, therefore, to document and analyze ethnobotanical data mainly related to the use of wild edible and nutraceutical plants in Raya-Azebo District in the Southern Zone of the Tigray Region, northern Ethiopia. Raya-Azebo District was prioritized for the study because of an ongoing decimation of WEPs in the area due to destruction of their natural habitats attributed to mainly expansion of agriculture [32] and largely by private investors, which in the absence of proper and immediate documentation could ultimately bring about the perpetual loss of the local knowledge and practices associated with the use of WEPs.

Methods

The study area

Raya-Azebo District belongs to the Southern zone of the Tigray Region in northern Ethiopia and is located at latitudes between 12o 15’and 13o 41’ North and longitudes between 38o 59’and 39o 54’ East [33]. Raya-Azebo covers an area of about176, 210 ha [34]. The district is divided into 18 rural and two urban tabiyas (sub-districts) [35], and has a human population of 135, 870, of which 67,687 are men and 68,183 are women [36]. Ninety percent of the total area in the district is midland (1500–2300 m above sea level) while 10% is lowland (< 1500 m above sea level) [34]. The district gets its main rainfall between July and September and light rainfall between February and April. Agriculture is the main economic stay in the district. Sorghum and maize are the crops that are widely cultivated in the area. Malaria is the leading disease in the district causing high morbidity (unpublished data, Raya-Azebo District Health Office, 2015).

Selection of study areas and informants

For the study, nine tabiyas that were relatively considered to have better vegetation cover and availability of knowledgeable individuals concerning use of WEPs were purposively sampled out of the total 18 rural tabiyas of the district with the help of experts at Raya-Azebo District Agriculture and Natural Resources Conservation Office. The selected tabiyas included Ebo, Erba, Genete, Hade Alga, Hadis Kigni, Hawelti, Mechare, Tsigea and Ulaga (Fig. 1). For the interview survey, a total of 180 informants constituting 158 men and 22 women aged 20 years and above were involved; 20 informants from each of the nine sampled tabiyas that were considered the most knowledgeable with regard to use of wild edible and nutraceutical plants were purposively identified and sampled with the help of tabiya administrators and elders.

Methods of data collection

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in the study District between July 2017 and October 2018 and ethnobotanical data were collected through individual interviews that were held with the purposively selected informants using a pre-tested list of interview items (semi-structured questionnaire), field observation and market surveys following the methods stated in Martin [37]. Attempt was made to make the data collection process valid and reliable through the strict of use of pre-tested. Data collected mainly included local name of each claimed edible plant, edible part, maturity level at the time of collection, month of harvest, processing method, taste, habitat, availability status and potential threats. Additional data were collected concerning the medicinal (nutraceutical) value of each claimed edible plant. Voucher specimens were collected for most of the claimed WEPs plants and identified, and duplicates were deposited at the National Herbarium of the Addis Ababa University (AAU) and the mini-herbarium of the Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology (ALIPB), AAU.

Data analysis

Microsoft Excel version 2016 was employed to enter and organize the data. Descriptive statistical methods were used to analyze and summarize the data using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16. Comparison of mean differences between informant groups was made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and differences in means with p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Mean values are presented as mean plus or minus standard error of the mean (mean ± SEM). Preference ranking exercises were performed on WEPs of the highest informant consensus by involving individuals randomly sampled from the list of informants who participated in interviews following the method of Martin [37]. Preference ranking exercises were additionally conducted by the same randomly sampled individuals to identify main factors responsible for the depletion of WEPs. The relative healing potential of each nutraceutical plant cited by three or more informants for its use to manage a specific ailment was estimated by using an index called Fidelity Level (FL) with the formula FL = Ip/Iu × 100, where Ip/Iu × 100, where Ip is the number of informants who reported the utilization of the nutraceutical plant against a specific ailment and Iu is the total number of informants who mentioned the use of same plant against any ailment [38]. However, plants with similar FL values but known to different numbers of informants may differ in their healing potential. To differentiate the healing potential of plants of similar FL values, there is a need to calculate a correlation index known as relative popularity level (RPL) and determine rank order priority (ROP) value by multiplying FL value by RPL value [38]. RPL values range between 0 and 1. Plants are categorized into “popular” (RPL = 1) and “unpopular” (RPL < 1) groups. Popular plant are those cited by half or more of the highest number of informants (29 in the current study) who cited a given plant against any ailment. Accordingly, a medicinal plant cited by 15 or more of informants for its use against any ailment in the study District was considered popular and was assigned with an RPL value of 1, whereas a medicinal plant that was mentioned by less than 15 informants for its use against any ailment was considered unpopular and was assigned with RPL value less than 1 and was determined by dividing the total number of informants who mentioned the given plant against any ailment by 15.

Results

Diversity of wild edible plants

The study documented a total of 59 WEPs, of which 51 (belonging to 33 families and 40 genera) were, at least, identified to a genus level (44 to a species level and seven to genus level). The remaining eight species were only known by their Tigrigna names, as informants were not willing to travel to far distances to collect their specimens for identification purpose (Table 1). The families Asclepiadaceae, Fabaceae and Tiliaceae were represented by four species each, and the families Brassicaceae and Moraceae were represented by three species each. The families Anacardiaceae, Boraginaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Polygonaceae, Rhamnaceae and Rosaceae were represented by two species each, while the remaining 21 species were represented by a single species each. Of all the 40 genera recorded, the genus Grewia contributed four species, the genera Acacia and Ficus contributed three species each, and the genera Rhus, Cordia, Brassica, Dovyalis and Rumex contributed two species each, while the remaining 31 genera were represented by one species each. Of the plants that were determined, at least, to a genus level, 18(35%) were shrubs, 18 (35%) were herbs and 15 (29%) were trees.

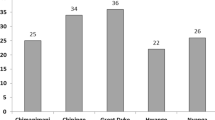

Part consumed, taste, level of maturity at consumption and storage

The majority (57.63%) of the WEPs in the study area were sought for their fruits, and few were harvested for their leaves (13.60%) and roots (8.5%) (Fig. 2). The edible fruits were claimed to have different tastes (sweet, sour, bitter) with the great majority having a sweet taste. The fruits were consumed when they got ripe, mostly characterized by color change from green to yellow, dark, purple or red. However, leafy vegetables were claimed to be consumed at their juvenile stage. There was little practice of storing WEPs in the area and thus the great majority of them were reported to be consumed immediately after harvesting while they were fresh.

Preparation of edible parts and conditions of consumption

Most fruits were consumed raw by peeling off their skin (exocarp) and then chewing and swallowing with occasional spitting of seeds or stones (Table 1). On the other hand, the majority of the leafy vegetables were processed mainly by chopping, boiling and squeezing, and most frequently consumed with injera (pan-cake-like flatbread made of Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter).

The great majority of the wild edible plants in the study area were frequently harvested and consumed as supplementary/complementary foods at time of plenty or seasonal shortage of staple food. However, some (Amaranthus hybridus L., Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medic., Cleome gynandra L., Commiphora Africana (A.Rich.) Engl., Cynanchum abyssinicum Decne., Echidnopsis sp., Huernia macrocarpa (A.Rich.) Sprenger, Eragrostis sp., Dobera glabra (Forssk.) Pair., Pentarrbinum insipidum E.Mey and Rumex nervosus Vahl) were only consumed at times of famine as reported by informants. Fruits were predominantly consumed by children, especially when herding animals in places that were far away from homesteads. On the other hand, leafy vegetables were usually harvested by women and prepared at home for household consumption.

Season availability of wild edible plants

Analysis of data shows that the highest number of WEPs (49 species) in the study district were available for harvest in the autumn season (locally known as qewei), followed by those (37 species) that were harvested in the summer season (locally known as kiremti). The autumn season, which includes the months of September, October and November, comes after the long rainy summer season that includes the months of June, July and August. Twenty-six WEPs were consumed in the winter season (which includes the months of December, January and February), and 25 plants were consumed in the spring season which includes the months of March, April and May (Table 2). In terms of months, the highest number of WEPs was claimed to be consumed in September (43 species), followed by those consumed August (37 species), July (33 species), October (31 species) and November (31species). Some were consumed December (26 species), April (24 species), May (24 species), March (23 species), January (21 species), February (19 species) and June (18 species). The species Acacia abyssinica Hochst. ex Benth., Acacia seyal Del., Balanites aegyptiaca, Carissa spinarum L., Cordia monoica Roxb., Cynanchum abyssinicum Decne., Grewia sp., Grewia villosa Willd., Huernia macrocarpa, Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata (Wall. ex G.Don) cif. and Rhus natalensis Krauss, Smilax aspera L., and a plant locally known as katoita were reported to be available for harvest throughout the year.

Popular wild edible plants

Based on the number of informant citations, Ziziphus spina-christi, Balanites aegyptiaca and Opuntia ficus-indica were found to be the most popular WEPs in the district, cited by 142, 134 and 121 informants, respectively (Table 1). Other WEPs that were found popular include Carissa spinarum, Cynanchum abyssinicum, Grewia sp., Ximenia Americana L., Grewia villosa, Cleome gynandra, Huernia macrocarpa, Cordia monoica, Ficus sur and Rhus natalensis, reported by 97, 81, 68, 65, 45, 42, 29, 25, 20 and 20 informants, respectively (Table 1). A simple preference ranking exercise conducted on seven WEPs of the highest informant citations revealed Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi and Balanites aegyptiaca as the most preferred plants in the district (Table 3).

Marketability

Interviews data showed that Carissa spinarum, Sageretia thea (Osbeck) M.C. Johnston, Grewia villosa, Balanites aegyptiaca, Ficus vasta, Dovyalis abyssinica (A.Rich.) Warb., Ximenia americana, Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Ficus sur and Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. ex. A.DC. were sold at local markets for their food values. Whereas, market surveys witnessed the marketability of only four of the aforementioned plants that included Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Ficus vasta, Ficus sur and Balanites aegyptiaca.

Habitat, availability and threats

Most of the WEPs consumed in the study area were harvested from farmlands and other disturbed habitats, roadsides, and woodlands. Very few were harvested from forested area. Nearly half of the reported WEPs were reported to have scarce occurrence in the area with the population of each plant continuing to decline from time to time. However, as interview reports indicated, very little effort has so far been made in the area to spare them from further devastation. The frequently mentioned threats of WEPs in the study area included agricultural expansion, recurrent drought and cutting of trees (for firewood purpose, house construction, making of farm tools, household utensils and fences). Ranking exercise conducted by informants revealed agricultural expansion and cutting of trees for firewood making as the main factors responsible for the depletion of WEPs in the district (Table 4). Of the claimed WEPs, Ficus sur, Rhus natalensis, Ximenia americana and Ziziphus spina-christi were reported to have rare occurrences in the study area.

Comparison of knowledge on wild edible plants among different social groups

Analysis of data collected revealed that there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the mean number of WEPs reported by literate and illiterate informants; the mean number WEPs reported by literate and illiterate informants were 6.69 ± 0.37and 5.45 ± 0.22, respectively. However, there was no significant difference in the number of WEPs reported by male (6.08 ± 0.23) and female (4.90 ± 0.43) informants, and those reported by informants above the age of 40 years and above (5.94 ± 0.23) and those who were below the age of 40 years (5.94 ± 0.52).

Wild edible plants claimed to have medicinal values

Of the total recorded WEPs in the study district, 21 were reported to also have medicinal (nutraceutical) uses (Table 5). Of these, the plants Balanites aegyptiaca and Acacia etbaica Schweinf. had the highest informant agreement, reported by 17 and seven informants for their uses to manage anthrax and skin infections, respectively. Balanites aegyptiaca and Acacia etbaica also scored the highest rank order priority (ROP) values. Balanites aegyptiaca scored RPO value of 58.6 for its use to treat anthrax, and Acacia etbaica scored an RPO value of 43.8 for its use to manage skin infections (Table 6).

Discussion

Results of the current study demonstrates that there is a wide use of wild edible as supplementary/complementary foods and nutraceuticals in Raya-Azebo District of the Tigray Region as revealed by the high diversity of the reported plant species. Relatively higher number of WEPs (59 species) was recorded from the study District as compared with those reported from other districts of the same region by Girmay et al. in Asgede Tsimbla, Tahtay Koraro and Medebay Zana districts (41 spp.) [39], Adhena in Raya Alamata District (37 spp.) [30], and Habtu in Wukro Kilte Awulaelo District (30 spp.) [31]. The wide use of WEPs in the district could be attributed to their good nutritional value as well as to the often-poor harvest of cultivated crops in the district mainly due to recurrent drought occurring in that part of the country [40, 41]. Based on literature survey, all the WEPs identified to a species level, except three (Smilax aspera, Cynanchum abyssinicum and Pentarrbinum insipidum), were also found to be consumed elsewhere in the country, which may be related to their better preference and/or wide occurrence in different agro-ecological zones of the country.

The fact that the families Asclepiadaceae and Fabaceae and Tiliaceae contributed a relatively higher number of wild edible species could be due to a combination of factors that, among others, may include their species diversity in Ethiopia and/or better nutritional value. Fabaceae is one of the few dominant dicotyledonous families in Ethiopia contributing 486 species [42]. This family is also rich in species that have high protein content [43]. The other two families, Asclepiadaceae and Tiliaceae, also have relatively fair diversity in the country, represented by170 [44] and 47 [45] species, respectively. Studies conducted in other parts of the country also show the common use of wild edible species belonging to the aforementioned three families [14, 17, 20, 22,23,24, 27, 30, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Most WEPs in the study district were found to be shrubby species, which may demonstrate the better availability of the same for harvest throughout the year. Studies carried out elsewhere in the country also reported the common use of wild shrubby plants as a source of food [14, 20, 22, 27, 39, 48,49,50,51,52, 54, 58,59,60].

Most of the WEPs in the district were sought for their fruits, which could be due to rich nutritional content and good taste of fruits as also claimed by informants involved in the study. Many other studies conducted elsewhere in the country also witnessed the dominance of wild edible fruits [17, 19,20,21,22,23,24, 27, 30, 31, 39, 46, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

The fact that there was little practice of harvesting and storing WEPs in the study district for later consumption may be attributed to the perishable nature of the consumed parts, especially the fruits and leaves, which were reported to be popular. Studies conducted elsewhere in Ethiopia also reported the perishability of wild fruits and leaves [62, 71], indicating their inconvenience for long-term storage. The common consumption of raw wild edible fruits may be taken as an effort to reduce the loss of nutritional values caused by boiling. Reports of similar studies conducted elsewhere in the country also showed the wide consumption of raw fruits [20, 22, 30, 31, 39, 47,48,49,50, 52, 54, 55, 58, 65, 67,68,69].

The majority of the WEPs in the district were harvested and consumed during the summer and autumn seasons including June, July, August, September, October and November, and that may attributed to the fact that their edible parts (mostly fruits) abundantly ripen at that time of the year. Several studies conducted in different parts of the country also reported better harvest and consumption of WEPs in the aforementioned seasons [30, 39, 57,58,59, 64, 68, 73] during which people often face a critical shortage of food. The species Acacia abyssinica, Acacia seyal, Balanites aegyptiaca, Carissa spinarum, Cordia monoica, Cynanchum abyssinicum, Grewia sp., Grewia villosa, Huernia macrocarpa, Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata and Rhus natalensis, Smilax aspera, and a plant locally known as katoita were revealed to be harvested and consumed year-round because of the availability of their edible parts, although the yield each plant may differ from season to season.

Ziziphus spina-christi, Balanites aegyptiaca and Opuntia ficus-indica were revealed as the most popular and preferred plants in the district, which may be attributed to their good harvest, taste and nutritional value. The fact that the three plants served as a good source of financial income, as also noted during interviews and market surveys, could have also contributed to their popularity. These plants were also found popular elsewhere in the northern part of the country [30, 31, 39, 55, 56, 64]. Laboratory investigation conducted elsewhere demonstrated the richness of Ziziphus spina-christi in fiber, carbohydrate and different minerals [74, 75], Balanites aegyptiaca in protein, fiber and different minerals [74,75,76], and Opuntia ficus-indica in carbohydrate, fiber and vitamin C [77, 78]. Preference ranking exercise revealed agricultural expansion and cutting of trees for their use as firewood as the leading factors for the depletion of WEPs in the district, which is also the case in many other parts of the country [19,20,21, 23, 24, 29,30,31, 39, 50, 52, 55, 56, 64, 66].

Analysis of data revealed that literate people (those who read and write) had better knowledge of the use of WEPs plants as compared to illiterate ones (those who do not read and write), which was in contrast to results of some studies conducted elsewhere in the country where illiterate people are more knowledgeable than literate ones [39, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. Education of most of the literate people in the study area is linked to religious institutions (mostly Christianity) and that might have contributed to their better knowledge of WEPs. Some manuscripts belonging to Christianity in different parts of the world often provide information on useful plants including medicinal and wild edible plants [79, 80].

Of the WEPs reported to have medicinal (nutraceutical) values in the study district, Balanites aegyptiaca and Acacia etbaica scored the highest rank order priority (ROP) values, Balanites aegyptiaca for its use to treat anthrax and Acacia etbaica for its use to manage skin infections. Investigations conducted elsewhere in the country also revealed the use of Acacia etbaica against skin infection [81,82,83], and the use of Balanites aegyptiaca against anthrax [84, 85]. Furthermore, some investigations demonstrated the antibacterial properties of Acacia etbaica [86, 87] and Balanites aegyptiaca [88,89,90], which corroborate the local uses of the two plants against the aforementioned health problems.

Conclusions

The current investigation demonstrated a wide use of WEPs in Raya-Azebo district as revealed by the high diversity of recorded plants (59 species), the majority of which were sought for their fruits. Most of the plants were consumed, as supplementary foods, and often by children. The highest number of WEPs was consumed in the autumn season, which includes the months of September, October and November from which September took the lead. The plants Ziziphus spina-christi, Balanites aegyptiaca and Opuntia ficus-indica were found to be the most preferred WEPs. Agricultural expansion and cutting of trees for firewood purpose were found to be the main conservation threats for WEPs. Of the total WEPs, 21 were reported to also have medicinal (nutraceutical) values. Balanites aegyptiaca and Acacia etbaica scored the highest rank order priority (ROP) values, the former for its use to treat anthrax and the later for its use to manage skin infections. In future evaluation of the nutritional value of the documented WEPs, priority should be given to those that were found popular in the study district. Likewise, priority should be given to nutraceutical plants that scored the highest ROP values in the investigation of pharmacological properties and phytochemical profiles. Furthermore, immediate attention should be given by concerned individuals and institutions in the country to manage (in situ and ex situ) wild edible and nutraceutical plants that were reported to have rare occurrences in the study District by involving the local community.

Availability of data and materials

Data related to this study were stored in a desktop computer available at Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology (ALIPB), Addis Ababa University (AAU). Readers may get access to the data through request made to ALIPB. Plant voucher specimens have been deposited at the mini-herbarium of Endod and Other Medicinal Plants Research Unit, ALIPB, AAU.

Abbreviations

- AAU:

-

Addis Ababa University

- ALIPB:

-

Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- FL:

-

Fidelity level

- ROP:

-

Rank order priority

- RPL:

-

Relative popularity level

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- WEPs:

-

Wild edible plants

References

Turner NJ, Łuczaj ŁJ, Migliorini P, Pieroni A, Dreon AL, Sacchetti LE, et al. Edible and tended wild plants, traditional ecological knowledge and agroecology. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2011;30:198–225.

McNamara KE, Prasad SS. Valuing indigenous knowledge for climate change adaptation planning in Fiji and Vanuatu. Traditional Knowledge Bulletin. Darwin: United Nations University, 2013. http://www.unutki.org/downloads/File/Publications/TK%20.Bulletin%20Articles/2013-07%20McNamara_Prasad_Vanuatu.pdf. Accessed 31 Jul 2015.

Azam FMS, Biswas A, Mannan A, Afsana NA, Jahan R, Rahmatullah M. Are famine food plants also ethnomedicinal plants? An ethnomedicinal appraisal of famine food plants of two districts of Bangladesh. Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/741712.

Erskine W, Ximenes A, Glazebrook D, da Costa M, Lopes M, Spyckerelle L, et al. The role of wild foods in food security: the example of Timor-Leste. Food Secur. 2015;7:55–65.

Khan FA, Bhat SA, Narayan S. Wild edible plants as a food resource: traditional knowledge. 2017; =https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34547.53285.

Gockowski J, Mbazo’o J, Mbah G, Moulende TF. African traditional leafy vegetables and the urban and peri-urban poor. Food Policy. 2003;28:221–35.

Neudeck L, Avelino L, Bareetseng P, Ngwenya BN, Teketay D, Motsholapheko MR. The Contribution of edible wild plants to food security, dietary diversity and income of households in Shorobe Village. Northern Botswana Ethnobot Res Appl. 2012;10:449–62.

Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Shrestha KK, Rajbhandary S, Tiwari NN, Shrestha UB, Asselin H. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:16.

Ju Y, Zhuo J, Liu B, Long C. Eating from the wild: diversity of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:28.

Benítez G, Molero-Mesa J, Tejero MRG. Gathering an edible wild plant: food or medicine? A case study on wild edibles and functional foods in Granada. Spain Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2017;86:3550.

Shikov AN, Tsitsilin AN, Pozharitskaya ON, Makarov VG, Heinrich M. Traditional and Current food use of wild plants listed in the Russian Pharmacopoeia. Front pharmacol. 2017;8:841.

Hinnawi NSA. An ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in the Northern West Bank, Palestine. MSc thesis, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine; 2010.

Sansanelli S, Ferri M, Salinitro M, Tassoni A. Ethnobotanical survey of wild food plants traditionally collected and consumed in the Middle Agri Valley (Basilicata Region, Southern Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:50.

Balemie K, Kebebew F. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Derashe and Kucha districts, South Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:53.

Teklehaymanot T, Giday M. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants of Kara and Kwego semi-pastoralist people in Lower Omo River Valley, Debub Omo Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:23.

Feyssa DH, Njoka JT, Asfaw Z, Nyangito MM. Seasonal availability and consumption of wild edible plants in semiarid Ethiopia: implications to food security and climate change adaptation. J Hortic For. 2011;3:138–49.

Assefa A, Abebe T. Wild edible trees and shrubs in the semi-arid lowlands of Southern Ethiopia. J Sci Dev. 2011;1:5–19.

Addis G, Asfaw Z, Woldu Z. Ethnobotany of Wild and Semi-wild Edible Plants of Konso Ethnic Community, South Ethiopia. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2013;11:121–41.

Tebkew M, Asfaw Z, Zewudie S. Underutilized wild edible plants in the Chilga District, northwestern Ethiopia: focus on wild woody plants. Agric Food Secur. 2014;3:12.

Alemayehu G, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E. Plant diversity and ethnobotany in Berehet District, North Shewa Zone of Amhara Region (Ethiopia) with emphasis on wild edible plants. J Med Plants Stud. 2015;3:93–105.

Meragiaw M, Asfaw Z, Argaw M. Indigenous knowledge (IK) of wild edible plants (WEPs) and impacts of resettlement in Delanta, Northern Ethiopia. Res Rev J Herb Med. 2015;4:8–26.

Ashagre M, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Burji District, Segan Area Zone of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12:32.

Berihun T, Molla E. Study on the diversity and use of wild edible plants in Bullen District Northwest Ethiopia. J Bot 2017;2017. Article ID 8383468.

Tebkew M, Gebremariam Y, Mucheye T, Alemu A, Abich A, Fikir D. Uses of wild edible plants in Quara District, northwest Ethiopia: implication for forest management. Agric Food Secur. 2018;7:12.

Chekole G. An ethnobotanical study of plants used in traditional medicine and as wild foods in and around Tara Gedam and Amba remnant forests in Libo Kemkem Wereda, South Gonder Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2011.

Feyssa DH, Njoka JT, Nyangito MM, Asfaw Z. Nutraceutical wild plants of semiarid East Shewa, Ethiopia: contributions to food and healthcare security of the semiarid people. Res J For. 2011;5:1–16.

Meragiaw M. Wild useful plants with emphasis on traditional use of medicinal and edible plants by the people of Aba’ala, North-eastern Ethiopia. J Med Plant. 2016;4:1–16.

Bilal MS. Floristic composition of woody vegetation with emphasis to Ethnobotanical importance of Wild Legumes in Laelay and Tahtay Maichew districts, Central zone, Tigray, Ethiopia. MSC thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa; 2012.

Tewelde F. Marketable medicinal, edible and spice plants in Endasilase-Shire District Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia. Res J Med Sci. 2018;13:1–6.

Adhena A. Ethnobotanical study of wild and semi-wild edible plants in and around Tselim-dur Forest of Raya Alamata Woreda, Tigray National Regional State of Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa; 2019.

Habtu M. Study on wild and semi-wild edible plants in Wukro Kilte-Awulaelo, Eastern Zone of Tigray Administrative Region, Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa; 2019.

Gidey E, Dikinya O, Sebego R, Segosebe E, Zenebe A, Mussa S, Mhangara P, Birhane E. Land use and land cover change determinants in Raya Valley, Tigray, Northern Ethiopian Highlands. Agriculture. 2023;13:507.

Gedif B, Hadish L, Addisu S, Suryabhagavan KV. Drought risk assessment using remote sensing and GIS: the case of Southern Zone, Tigray Region, Ethiopia. J Nat Sci Res. 2014;4:87–94.

Tesfay G, Gebresamuel G, Gebretsadik A, Gebrelibanos A, Gebremeskel Y, Hagos T. Participatory rural appraisal report: Raya-Azebo Woreda, Tigray Region. Cascape working paper 2.6.5, 2014. http://www.cascape.info. Accessed 21 Nov 2016.

Giday M. Traditional knowledge of people on plants used as insect repellents and insecticides in Raya-Azebo district, Tigray region of Ethiopia. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2018;17:336–43.

Tesfay K, Yohannes M, Bayisa S. Trend analysis of malaria prevalence in Raya Azebo district, Northern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:900.

Martin GJ. Ethnobotany: a method manual. London: Chapman and Hall; 1995.

Friedman J, Yaniv Z, Dafni A, Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert. Israel J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;16:275–87.

Girmay G, Lulekal E, Belay B, Gebrehiwot K. Wild edible plants study in a dryland ecosystem of Ethiopia. Daagu Int J Basic Appl Res. 2022;4:105–19.

Berg T, Aune J. Integrated agricultural development programme, central Tigray. Ethiopia: The Relief Society of Tigray (REST); 1997.

Wilson RT. Coping with catastrophe: contributing to food security through crop diversity and crop production in Tigray National Regional State in northern Ethiopia. Res Sq. 2021. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-937220/v1.

Fabaceae TM. In: Hedberg I, Edwards S, eds., Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Volume 3: Pittosporaceae to Araliaceae, National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 1989, pp. 49-251.

Edwards S, Gebre Egziabher T, Tewolde-Berhan S, Asfaw Z, Ruelle R, Nebiyu A, Power AS, Tana T, Dejen A, Tsegay A, Woldu Z. A Guide to Edible Legumes Found in Ethiopia: for Extension Officers and Researchers. Published by Mekelle University Press; 2019. ISBN 978-99944-74-56-1.

Goyder et al. Asclepiadaceae. In: Hedberg I, Edwards S, Nemomissa S, eds., Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Volume 4, Part 1: Apiaceae to Dipsacaceae, National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2003, pp. 99-193.

Vollesen K, Demissew S. Tiliaceae. In: Edwards, S, Mesfin T., Hedberg, I., eds., Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Volume 2, Part 2: Canellaceae to Euphorbiaceae, National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 1995, pp. 145-164

Awas T. A study on the ecology and ethnobotany of non-cultivated food plants and wild relatives of cultivated crops in Gambella Region, Southwestern Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa; 1997.

Kidane B, van der Maesen LJG, van Andel T, Asfaw Z, Sosef MSM. Ethnobotany of wild and semi-wild edible fruit species used by Maale and Ari Ethnic communities in Southern Ethiopia. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2014;12:455–71.

Anbessa B. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Bule Hora Woreda, Southern Ethiopia. Afr J Basic Appl Sci. 2016;8:198–207.

Kebebew M, Leta G. Wild edible plant bio-diversity and utilization system in Nech Sar National Park, Ethiopia. Int J Bio-Resour Stress Manag. 2016;7:885–96.

Alemayehu G. Plant Diversity and ethnobotanny of medicinal and wild edible plants in Amaro District of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region and Gelana District of Oromia Region, Southern Ethiopia. PhD thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa; 2017.

Ayele D. Ethnobotanical Survey of wild edible plants and their contribution for food security Used by Gumuz people in Kamash Woreda, Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia. J Food Nutr Sci. 2017;5:217–24.

Ayele D, Negasa D. Identification, characterization and documentation of medicinal and wild edible plants in Kashaf Kebele, Menge Woreda, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5:193–204.

Kebede A, Tesfaye W, Fentie M, Zewide H. An Ethnobotanical survey of wild edible plants commercialized in Kefira Market, Dire Dawa City, Eastern Ethiopia. Plant. 2017;5:42–6.

Degualem A. Wild edible plant resources in Guangua and Banja districts and contribution for food security. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa; 2018.

Demeke M. Ethnobotanical study of wild and semi-wild edible plants in and around GraKahsu Forrest of Raya Alamata District, Tigray, Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia; 2020.

Hassen A. Diversity and potential contribution of wild edible plants to sustainable food security in North Wollo, Ethiopia. Biodiversitas. 2021;22:2501–10.

Yimer A, Forsido SF, Addis A, Ayelgn A. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants used by Meinit Ethnic Community at Bench-Maji Zone Southwest Ethiopia. Res Sq. 2021. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-907812/v1.

Abera M. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants and their indigenous knowledge in Sedie Muja district, South Gondar Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia. Am J Plant Sci. 2022;13:241–64.

Tahir M, Abrahim A, Beyene T, Dinsa G, Guluma T, Alemneh Y, Van Damme P, Geletu US, Mohammed A. The traditional use of wild edible plants in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities of Mieso District, eastern Ethiopia. Trop Med Health. 2023;51:10.

Shiferaw M. Potential contribution of wild edible plants to urban safety net beneficiary households and determinants of collection and consumption of the plants in Addis Ababa. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2020.

Regassa T, Kelbessa E, Asfaw Z. Ethnobotany of wild and semi-wild edible plants of Chelia District, West-Central Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2014;3:122–34.

Tebkew M. Wild and semi-wild edible plants in Chilga District, Northwestern Ethiopia: implication for food security and climate change adaptation. Glob J Wood Sci Forest Wildlife. 2015;3:072–82.

Fugaro F, Maryo M. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Kedida Gamella Woreda, Kambatta Tembaro Zone, SNNPRS, Ethiopia. Int J Mod Pharm Res. 2018;2:01–9.

Terefe A. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants used by local communities in Mandura District, North West Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2019.

Waktole G. Assessments and identification of wild edible plants: the case of Sasiga District in East Wollega Zone of Oromia Regional National State, Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2019.

Alemneh D. Ethnobotany of wild edible plants in Yilmana Densa and Quarit Districts of West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2020;20:47.

Dejene T, Agamy MS, Agúndez D, Martin-Pinto P. Ethnobotanical survey of wild edible fruit tree species in lowland areas of Ethiopia. Forests. 2020;11:177. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11020177.

Demise S, Asfaw Z. Ethno botanical study of wild edible plants in Adola District, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Res Anal Rev. 2020;7:212–28.

Fikadu W. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Dedo District, Jimma Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Southwest Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia; 2020.

Nigusse R, Tesfay A. Floristic composition and diversity of wild and semi wild edible tree species in Central Zone of Tigrai, Northern Ethiopia. World J Pharm Life Sci. 2020;6:11–8.

Kidane L, Kejela A. Food security and environment conservation through sustainable use of wild and semi-wild edible plants: a case study in Berek Natural Forest, Oromia special zone, Ethiopia. Agric Food Secur. 2021;10:29.

Emire A, Demise S, Giri T, Tadele W. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Liben and Wadera districts of Guji Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Glob J Agric Res. 2022;10:47–65.

Guyu DF, Muluneh W. Wild foods (plants and animals) in the green famine belt of Ethiopia: do they contribute to household resilience to seasonal food insecurity? For Ecosyst. 2015;2:34.

Tafesse A. Nutritional quality of underutilized wild edible fruits grown in Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2018.

Mokria M, Gebretsadik Y, Birhane E, McMullin S, Ngethe E, Hadgu KM, Hagazi N, Tewolde-Berhan S. Nutritional and ecoclimatic importance of indigenous and naturalized wild edible plant species in Ethiopia. Food Chem. 2022;4:100084.

Feyssa DH, Njoka J, Asfaw Z, Nyangito MM. Nutritional contents of Balanites aegyptiaca and its contribution to human diet. Afr J Food Sci. 2015;9:346–50.

Chiteva R, Wairagu N. Chemical and nutritional content of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.). Afr J Biotechnol. 2013;12:3309–12.

Reda TH, Atsbha MK. Nutritional composition, antinutritional factors, antioxidant activities, functional properties, and sensory evaluation of cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) seeds grown in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Int J Food Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5697052.

Balick MJ, Cox PA. Plants, people and culture: the science of ethnobotany. New York: Scientific American Library; 1996.

Kibebew F. The status of availability of data of oral and written knowledge and traditional health care in Ethiopia. In: Zewdu M, Demissie A, editors. Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants in Ethiopia. Institute of Biodiversity Conservation and Research: Addis Ababa; 2001. p. 107–19.

Tefera BN, Kim YD. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Hawassa Zuria District, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2019;15:25.

Tadege T, Hintsa K, Weletnsae T, Gopalakrishnan VK, Muthulingam M, Kamalakararao K, Krishna CK. Phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial activities of leaf extract Acacia etbaica Schweinf against multidrug resistant Enterobacteriaceae human pathogens. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2020;11:4857–65.

Yimam M, Yimer SM, Beressa TB. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Artuma Fursi district, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Trop Med Health. 2022;50:85.

Seifu T. Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmaceutical studies on medicinal plants of Cifra District, Afar Region, Northeastern Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2004.

Giday M, Teklehaymanot T. Ethnobotanical study of plants used in management of livestock health problems by Afar people of Ada’ar District, Afar Regional State, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:8.

Getachew B, Getachew S, Mengiste B, Mekuria A. In-vitro antibacterial activity of Acacia etbaica against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Afr J Basic Appl Sci. 2015;7:219–22.

Abdullah AB, Al-zaemey A, Mudhesh Al-Husami RH, Al-Nowihi M. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Acacia etbaica water extract leafs against some pathogenic microorganisms. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 2021;2:1132–5.

Jahan N, Khatoon R, Shahzad A, Shahid M. Antimicrobial activity of medicinal plant Balanites aegyptiaca Del. and its in vitro raised calli against resistant organisms especially those harbouring bla genes. J Med Plants Res. 2013;7:1692–8.

Anani K, Adjrah Y, Améyapoh Y, Karou SD, Agbonon A, de Souza C, Gbeassor M. Antimicrobial activities of Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (Balanitaceae) on bacteria isolated from water well. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2015;5:052–8.

Khanam S, Galadima FZ. Antibacterial activity of Balanites aegyptiaca oil extract on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. bioRxiv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.23.436600.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Office of the Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer of Addis Ababa University (AAU) for the financial support to conduct this study. We are grateful to the staff of the Raya Azebo District administration, especially Mr. Haftu Kiros, for his commendable support in facilitating our research work in the district. We thank Mr. Melaku Wondafrash at the National Herbarium of AAU for his assistance in plant identification. Last, but not least, we are indebted to the informants in Raya Azebo District who generously shared their knowledge with us in relation to the use of wild edible plants in the district and participated in the collection of plant specimens.

Funding

The expenses of this research were covered by the Office of the Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer of Addis Ababa University (grant number: TR/036/2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG and TT collected the data, MG drafted the manuscript, and MG and TT edited, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of ALIPB, AAU (date: 19/10/2017; ref. no.: ALIPB/IRB/019/17). Approval to carry out the study was also received from the Office of the Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer, AAU (date: 25/11/2016; ref. no.: RD/PY-662/2016). Verbal consent to participate in the research was obtained from informants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There were no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giday, M., Teklehaymanot, T. Use of wild edible and nutraceutical plants in Raya-Azebo District of Tigray Region, northern Ethiopia. Trop Med Health 51, 58 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-023-00550-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-023-00550-8