Abstract

Background

Childhood diarrhea is one of the major public health problems in Ethiopia. Multiple factors at different levels contribute to the occurrence of childhood diarrhea. The objective of the study was to identify the factors affecting childhood diarrhea at individual and community level.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was employed from February to March 2015 in high and low hotspot districts of Awi and West and East Gojjam zones in Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia. Districts with high and low hotspots with childhood diarrhea were identified using SaTScan spatial statistical analysis. A total of 2495 households from ten (five high and five low hotspot) randomly selected districts were included in the study. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data. Data were entered and cleaned in Epi Info 3.5.2 version and analyzed using Stata version 12. A multilevel logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with childhood diarrhea.

Results

The prevalence of childhood diarrhea was 13.5 % and did not show significant variation between high [14.3 % (95 % CI 12.3–16.2 %)] and low [12.7 % (95 % CI 10.9–14.6 %)] hotspot districts. Individual- and community-level factors accounted for 35 % of childhood diarrhea variation across the communities in the full model. Age of children (6–35 months), complementary feeding initiation below 6 months, inadequate hand washing practices, limited knowledge of mothers on diarrhea, lowest wealth status of households, and longer time interval to visit households by health extension workers were factors for increasing the odds of childhood diarrhea at the individual level. At the community level, lack of improved water supply and sanitation and unvaccinated children with measles and rotavirus vaccine were the factors associated with childhood diarrhea.

Conclusions

In this study, childhood diarrhea occurrences remained high. Both individual- and community-level factors determined the occurrence of diarrhea. Interventions should consider both individual- and community-level factors to reduce the occurrence of childhood diarrhea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diarrhea remains one of the most common infectious diseases of children [1, 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that globally, approximately 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrhea occur each year [3]. Of the leading infectious causes of death worldwide, diarrhea was the second responsible for 578,000 deaths among children under 5 years of age in 2013 [2]. The burden of diarrheal diseases in developing countries is higher than developed countries [1, 4]. The greatest proportions of severe episodes of diarrhea occurred in the southeast Asian (26 %) and African regions (26 %) in 2010 [1].

In Sub-Saharan Africa, diarrhea accounted for 25 to 75 % childhood morbidity and 50 % childhood mortality [1]. In this region, rotavirus contributed the highest child death rate and remained the main cause of diarrhea [5]. In East Africa, the prevalence of childhood diarrhea was found in the range of 13–32 % [6–10]. Studies in different parts of Ethiopia showed that the prevalence of childhood diarrhea was in the range of 15–29 % [11–16]. However, the 2-week prevalence of childhood diarrhea at national level has shown a decline from 24 % in 2000 to 13.5 % in 2011 [6, 7].

Multiple factors contribute to the occurrence of diarrhea among children under 5 years of age. Childhood diarrhea was associated with low maternal education [8, 13, 15], age of children [8, 14–17], number of under five children [15, 17], latrine availability [15, 18], improper child stool disposal methods [15], mothers not practicing hand washing at critical times [13], lack of improved water sources [18–20], improper handling of drinking water [12, 16, 20], and improper refuse disposal [13, 14]. Systematic studies indicated diarrheal diseases, which are widespread in areas with water scarcity, unsafe drinking water supply, poor hygiene, and lack of sanitation which are poorly accessed [21, 22]. However, in rotavirus-vaccinated children, occurrence of childhood diarrhea decreased significantly [23–29].

In Ethiopia, including Amhara Region, provision of water supply and improvement in sanitation and hygiene have shown a progress in the past 10 years. According to WHO, the availability of improved drinking water supply in Ethiopia increased from 13 % in 1990 to 57 % in 2015 [30]. Improved and shared latrine facility availability in Amhara Region raised from 2 % in 2000 to 46 % in 2012 [31]. The promotion of hygiene and sanitation through the health extension program has been active since 2003 [32]. Rotavirus vaccine was launched in Ethiopia at the end of 2013 [33]. However, a facility-based report in Amhara Region showed that morbidity of childhood diarrhea was one of the top five leading cause of childhood morbidity in the past decade [34]. There is no recent information about childhood diarrhea at community level after implementation of the abovementioned interventions, particularly in the study area. Moreover, studies conducted in Ethiopia identified the determinants of childhood diarrhea using a standard logistic regression model, which has less power or increased type one error. Analyzing all factors at one level is likely to present a very incomplete picture on the evaluation of determinants of childhood diarrhea. The standard regression model assumes the presence of random variation between households, while neglecting the non-random variation of communities at different levels. An appropriate methodology is required for a more comprehensive and sound analysis.

Thus, a multilevel regression model, which controls the nesting effect of clusters at different levels, was used to account for the shortcomings of a standard logistic regression. The method was chosen for two reasons: First, it systematically analyzes the explanatory variables (covariate) at various levels of hierarchies that affect the outcome variable, or this model measures the interactions among covariates at different levels that affect the outcome variable. Second, it corrects the biases in parameter estimates resulting from clustering and provides correct standard errors [35]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify factors affecting childhood diarrhea at the individual and community level using multilevel regression analysis.

Methods

Study design and period

A cross-sectional study design was employed from February to March 2015 to assess the effect of individual- and community-level factors on childhood diarrhea in high and low hotspot districts.

Study area

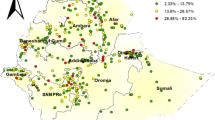

The study area included districts with high and low hotspots of childhood diarrhea in three (Awi and East and West Gojjam) zones in Amhara Regional State, northwest Ethiopia. Districts with high and low hotspots of childhood diarrhea were identified using SaTScan spatial statistical analysis. Of the 33 districts, 12 clusters, which covered 15 districts, were identified as a high hotspot of childhood diarrhea [36]. Eleven clusters, which encompassed 13 districts, were identified as a low hotspot of childhood diarrhea using the same data analysis procedure and these results are attached as supplement file (Additional file 1). The remaining five districts were non-significant districts (neither high nor low) in terms of childhood diarrhea spatial heterogeneity (Fig. 1).

Study population, sample size, and technique

All children under 5 years of age in randomly selected districts were the study population. Children who lived in the study area for at least 6 months were used as inclusion criteria. The sample size was determined using Epi Info version 3.5.2 statistical software considering the following assumptions: 95 % confidence level, 80 % power with 1:1 ratio of diarrhea in high and low hotspots districts, 1.5 odds ratio, and 18 % prevalence of childhood diarrhea in low hotspot districts [11]. The calculated sample size was 1208. By considering a design effect of 2 and 5 % non-response rate, the final sample size was 2544 (1272 in low hotspot and 1272 in high hotspot districts).

A multistage random sampling technique was implemented to select the study population. At the first stage, ten districts (five low and five high hotspot districts) were selected randomly. At the second stage, one urban and one rural kebele from each low and high hotspot randomly selected districts were chosen using simple random sampling technique. Proportional to size allocation was made for each district and each kebele within a district. Households from randomly selected urban and rural kebeles were chosen using a systematic random sampling technique. The total number of households in each kebele was divided by the allocated sample size to get the sampling interval. Mothers of the under-fives were the respondents in a household. If there were more than one mother with children under 5 years of age in the same household, one mother was selected by lottery method. If there was no child in the identified household, the next household was used as sampling unit.

Data collection tools

A structured questionnaire and observational checklist were used to collect data. The questionnaire was developed after reviewing related literatures and attached as supplement file (Additional file 2). The questionnaire includes variables on socio-demographic and economic data, knowledge of mothers/care takers on causes, transmission and prevention methods of childhood diarrhea, drinking water source and environmental sanitation, and childhood diarrhea in the past 2 weeks. Observational checklist was used to observe water storage container, the presence or absence of kitchen, availability and type of latrine, and presence or absence of hand washing facilities. The questionnaire was pre-tested in a similar setting after translating into the local language, Amharic. Data collectors and supervisors were recruited and then trained on the objective of the study and methods of the survey.

Measurement of outcome variable

The prevalence of childhood diarrhea was measured using the WHO-recommended definition, namely if a child had three or more loose stools or watery diarrhea in a day during the 2 weeks preceding the study [37].

Explanatory variables

Individual- and community-level variables that affect childhood diarrhea as described in Table 1 were included in the study. Coding for each explanatory variable and definitions of some of variables were also stated in the same table.

Comprehensive knowledge on diarrhea was categorized based on the mean score value of 13 items included in the questionnaire on the causes of diarrhea, means of transmission, and methods of prevention. These questions had “yes” or “no” responses, and a classification of “knowledgeable” was assigned if a respondent answered correctly seven or more items and “limited knowledge” if a respondent had six or less correct answers. Mothers were asked about their hand washing practices during critical times (after visiting a toilet, after cleaning a child’s bottom, after cleaning a house, before food preparation, before feeding a child, and before fetching water) and categorized based on mean score value, “practicing three or more hand washing critical times” and “practicing less than three hand washing critical times.”

Household wealth status was assessed as an indicator of socioeconomic status and was computed by principal component analysis from ten variables (presence of own farmland, own toilet facility, bank account, mobile phone, electricity, living house roofed with corrugated iron sheet, number of cows/oxen, horses/mules/donkeys, goats/sheep and chicken). Components resulting from the analysis were used to categorize households into three groups of wealth status (poor, medium, and rich) based on tercile.

Community-level factors were identified by global experts as indicators for evaluating diarrhea prevention activities at a given cluster or district (rotavirus and measles vaccine coverage, proportion of population with access to improved sanitation, proportion with access to improved drinking water); they were described in detail and published elsewhere [38].

Data quality assurance

The questionnaire was pretested to evaluate the face validity and to ensure whether the study participants understood what the investigators intended to know. Training was given to data collectors and supervisors on how to select household and study participants and interviewing techniques. Daily supervision was made by the principal investigator to check the completeness of the questionnaire and consistency of related data. Data were coded, entered, and cleaned using Epi Info version 3.5.2 statistical software.

Data analysis

Data were entered into Epi Info version 3.5.2 statistical software and exported to SPSS version 21. Data analysis was carried out using the statistical software Stata version 12. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data. Multilevel logistic regression was used to analyze factors associated with childhood diarrhea at individual and community levels. Multilevel regression analysis used the scheme on a random model [39], considering two levels of data organization. Four models were constructed for doing this regression analysis. The first model, an empty model, was without any explanatory variable to evaluate the extent of cluster variation affecting childhood diarrhea. The second model controlled for the individual-level variables, the third model controlled for community-level variables, while the fourth model controlled for both the individual- and community-level variables simultaneously. Those variables with a p value of less than 0.2 in the second and third models were retained for the final model. The p value of <0.05 was used to define statistical significance. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with the corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI) was calculated to identify factors affecting childhood diarrhea. Intra-cluster correlation (ICC), median odds ratio (MOR), and proportional change in variance (PCV) were calculated to measure the variation between clusters. ICC was used to explain cluster variation while MOR was used to measure unexplained cluster heterogeneity [40]. The ICC, MOR, and PCV formulae have been described elsewhere in detail [41–43].

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University. The committee provided ethical approval after reviewing informed verbal consent submitted with all components of the research protocol. Permission letters from the Amhara Regional Health Bureau and district health offices were also obtained before starting data collection. The verbal consent was included on the front page of the questionnaire below briefing statements. Data collection was done after briefing the purpose of the study. Before data collection, study participants were asked for their willingness/unwillingness by marking their yes/no response. After confirming their verbal consent, interview and observation of the housing condition and environmental sanitation were conducted. Study participants were informed to interrupt the interview on desire. Confidentiality was insured by collecting the data anonymously, and the questionnaires were kept locked.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Data were collected from 2544 households. Forty-nine (1.9 %) questionnaires were incomplete and were not included in the analysis. Of the completed data (2495), 1254 (50.3 %) and 1241 (49.7 %) were from high and low hotspot districts, respectively. Most participants in high (80.9 %) and low hotspot (85.7 %) districts lived in rural areas. The mean age of mothers was 29.5 (±6.1) in high and 29.6 (±6.7) in low hotspot districts. The overall mean age of mothers was 29.6 (±6.4) with a range of 20 and 70 years. The majority of mothers in high (51.1 %) and low (48.8 %) hotspot districts were found in the age range of 30–39 years. About 61.5 % of mothers in high and 71.8 % in low hotspot districts were unable to read and write. Nearly two third (64.4 %) of mothers in high and 79.1 % in low hotspot districts were farmers. Above 85 % of mothers in high (87.7 %) and low (93.4 %) hotspot districts were married and almost all mothers in both high (99 %) and low (98.7 %) hotspot areas were Orthodox Christian followers. Almost half of children in high (49.6 %) and 56.1 % in low hotspot districts were males. The mean age of children in high and low hotspot districts was 27.6 (±15.8) and 28.1 (±15.6) months, respectively. The overall mean age of children was 27.8 (±15.7) months. Nearly one fourth of children age in high and low hotspot areas were found in the range of 36–47 months. Almost equal percent of households in high (88.8 %) and low (89.2 %) hotspot districts had one child. Nearly one third of households in high (31.9 %) and 39 % in low hotspot districts had six and more family members. Thirty nine (34.9 %) of households in high and 25.9 % in low hotspot districts had a poor wealth index (Table 2).

Childhood diarrhea prevalence and related factors

The prevalence of childhood diarrhea was 14.3 % (95 % CI 12.3–16.2 %) in high and 12.7 % (95 % CI 10.9–14.6 %) in low hotspot districts. The overall prevalence of childhood diarrhea was 13.5 % (95 % CI 12.2–14.8%) in the study area. The proportion of children vaccinated with rotavirus vaccine was 63.3 % in high and 76.4 % in low hotspot districts, and the proportion of children vaccinated with measles vaccine were 82.0 % in high and 84.3 % in low hotspot districts. Children who started complementary feeding after 6 months were 79.7 and 77.4 % in high and low hotspot districts, respectively. About 35.0 % of mothers in high and 33.4 % in low hotspot districts had comprehensive knowledge on diarrhea. One third of mothers in high (32.9 %) and 30.4 % in low hotspot districts reported that they washed their hands at least three critical hand washing times (Table 3).

Above 60 % of households in high (63.0 %) and almost 60 % in low (59.8 %) hotspot districts used proper refuse disposal methods. Presence of latrine in the households was 75.6 % in high and 70.5 % in low hotspot districts, of which only 32.6 and 43.4 % had improved latrine facilities, respectively. Only 6.5 % of households in high and 3.1 % in low hotspot districts had hand washing container with water at a location nearby their latrine. About 61.2 % of households in high and 65.2 % in low hotspot districts used improved water for drinking and domestic purpose, and above half of households in high (55.3 %) and 88.2 % in low hotspot districts used pouring method to take water from a water storage container. More than 85 % of households in high and 64.1 % in low hotspot districts had separate kitchens for food preparation. Above three fourth of households in high (78.3 %) and 57.9 % in low hotspot districts had been visited by health extension workers once in every 3 months (Table 3).

Multilevel analysis

The results of multilevel logistic regression models for individual- and community-level factors are displayed in Table 4. Child sex, mother’s relation to a child, maternal education and occupation, family size, numbers of children, water handling, presence of kitchen, and availability of hand washing facility in the second model and spatial heterogeneity, place of residence, and refuse disposal methods in the third model did not show statistically significant association with childhood diarrhea. Of all the factors included in the full model for multilevel analysis, the child’s age, complementary feeding initiation at 6 months, hand washing practice at least three critical hands washing times, comprehensive knowledge on childhood diarrhea, wealth index, frequency of visitation by health extension workers, drinking water source, latrine status, and measles and rotavirus vaccination status were significantly associated with childhood diarrhea. The odds of developing childhood diarrhea among children in the age group between 6–11 months, 12–23 months, and 24–35 months were 5.87 times (AOR 5.87; 95 % CI 3.00–11.46), 3.31 times (AOR 3.31; 95% CI 2.07–5.29), and 1.80 times (AOR 1.80; 95 % CI 1.11–2.92) higher than those children whose age was greater than 47 months, respectively. The odds of developing childhood diarrhea among those children who started complementary feeding below 6 months were 6.81 times (AOR 6.81; 95 %CI 4.52–10.25) higher than those children who started complementary feeding above 6 months. The odds of having childhood diarrhea among children whose mothers failed to practice at least three hand washing critical times were 1.70 times (AOR 1.70; 95 % CI 1.20–2.40) higher than those children whose mothers practiced at least three critical times. The odds of developing childhood diarrhea among children whose mothers had limited comprehensive knowledge on childhood diarrhea were 1.45 times (AOR 1.45; 95 % CI 1.06–1.97) higher than those children whose mother had comprehensive knowledge on childhood diarrhea. The odds of having diarrhea in children who were from low/poor household wealth index were 1.63 times (AOR 1.63; 95 % CI 1.12–2.36) higher than those who were from the rich household wealth index. The odds of having diarrhea in children whose house revisit interval by health extension workers was longer than 6 months were 1.7 times (AOR 1.72; 95 % CI 1.13–2.60) higher than in children whose houses were revisited by health extension workers every 3 months (Table 4).

The odds of having diarrhea in children living in households with unimproved water source were 1.73 times (AOR 1.73; 95 % CI 1.27–2.34) higher than in children living in households with improved water source. The odds of having diarrhea in children living in households with no latrine facility and unimproved latrine were 2.43 (AOR 2.43; 95 % CI 1.61–3.63) and 1.84 (AOR 1.84; 95 % CI 1.23–2.75) times higher, respectively, than in children living in households with improved latrine facility. Those children who did not receive measles vaccine were 3.81 times (AOR 3.81; 95 % CI 1.91–7.58) more likely to develop diarrhea than those children who received measles vaccine, and those children who did not receive rotavirus vaccine were 4.88 times (AOR 4.88; 95 % CI 3.56–6.68) more likely to develop diarrhea than those children who received rotavirus vaccine (Table 4).

In a multilevel analysis, the empty model (the null model) revealed that childhood diarrhea was not random across the communities (τ 2 = 0.139, p < 0.001). Intra-cluster correlation based on estimated intercept component variance showed that the odds of childhood diarrhea could be attributed to the community-level factors. The full model, after adjusting for individual- and community-level factors, has shown that the variation in childhood diarrhea across the community remained statistically significant. The variance of both the individual- and the community-level random effect was 0.085 and the intra-cluster correlation coefficient was 2.3 %. About 35.1 % in the odds of childhood diarrhea variation across the communities was observed by the full model. Moreover, MOR also confirmed that childhood diarrhea was attributed to community-level factors. The MOR for childhood diarrhea was 1.5 in the empty model; this indicated that there is variation across communities compared to no variation across communities if MOR is 1. The unexplained community variation in childhood diarrhea decreased to an MOR of 1.4 when all factors were added to the null model (empty model). This value confirmed that there were also unexplained variations between communities that contribute for the occurrences of childhood diarrhea (Table 5).

Discussion

The overall prevalence of childhood diarrhea in our study area was 13.5 % (95 % CI 12.2–14.8 %), which is similar to the national prevalence reported by Demographic Health Survey result done in 2011 [7]. However, it is lower than studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia, such as in Keffa Sheka zone of southern Ethiopia (15 %) [16], in Mecha District of northwest Ethiopia (18 %) [11], in Kersa District of western Ethiopia (22.5 %) [14], and in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, northwest Ethiopia (22.1 %) [15]. The difference might be attributed to the difference in the socio-demographic characteristics and basic environmental infrastructure of study households, behaviors of care givers, and the study period. The lower prevalence may be due to the combination of interventions to improve child health, such as water, sanitation and hygiene interventions, breastfeeding, vitamin A supplementation, and vaccines for diarrhea (rotavirus vaccine) [44]. For instance, the rotavirus vaccine was launched in Ethiopia at the beginning of 2014 [33] and sanitation facility coverage improved from 2 % in 2000 to 46 % in 2012 [31] in the past decade in Amhara Region.

This study revealed that the prevalence of childhood diarrhea did not show a statistically significant variation between high (14.3 %) and low (12.3 %) hotspot districts. The possible explanation may be due to the government strategies to improve child health, including prevention of childhood diarrhea, through the implementation of health extension packages that could produce a similar impact in the study area and possibly in the region and the country [32]. The other possible reason may be due to the inherent drawback of cross-sectional study design used in this study that reflects one time or snapshot results unlike spatial analysis that used longitudinal retrospective data of 7 years [45].

This study confirmed that the variation in childhood diarrhea is attributed to individual- and community-level factors. In the full model, both individual- and community-level factors accounted for about 35 % of the variations observed for childhood diarrhea. Child age was one of the factors associated with childhood diarrhea in this study. The risk was most at age segments of 6–11 months, high at 12–23 months and 24–35 months, and least at 0–5 months compared to children aged above 47 months. This finding is in agreement with other studies [8, 14, 46–51]. The low risk of diarrhea during the age 0–5 months may be attributed to the protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding and less exposure of children to contaminated agents. The peak risk of diarrhea among children between the ages of 6–11 months could be due to crawling on the ground or walking which increases the probability of getting and contacting with filth materials that may expose to pathogenic microorganisms [52]. In addition, the complementary food practices which usually start after 6 months may increase the incidence of diarrhea diseases if the food preparation could not be done in a hygienic manner. In support of this, there exists evidence that the risk of complementary feeding as a result of contamination increases diarrhea in this age group [47, 53–55] and decreases subsequently after 6–11 months; this is probably because the children begin to develop immunity to pathogens after repeated exposure [55].

The findings of this study suggest that the risk of diarrhea among children who started complementary foods before 6 months was higher than those who started at or after 6 months. This finding is similar to other studies [8, 11, 46]. The time to initiate complementary feeding practice can reflect the duration of exclusive breastfeeding, which is an effective means of protecting children from diarrheal disease [56]. There is evidence of the protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding from diarrhea in the presence of improved water supply and sanitation; this effect was found statistically significant compared to the partially breastfed and the non-exclusive breastfeeding children [57, 58]. The possible justifications could be due to the fact that unhygienic complementary feeding practices increase the risk of diarrhea [59], exclusive breastfeeding even later than 6 months can reduce exposure to infection in areas where environmental sanitation is very poor, and the immunologic properties of breast milk protect children against infection.

The results of this study showed that the risk of diarrhea among children from poor households was higher than children from rich households, and this is in agreement with other studies [8, 60, 61]. This may indicate that people in rich households are more likely to apply better hygienic practices and environmental sanitation because of their living standard, and this may prevent childhood diarrhea occurrence [62, 63].

The finding of the study is consistent with earlier studies, which found higher odds of childhood diarrhea among children whose mothers failed to wash their hands at hand washing critical times [60, 64–66]. Moreover, this study found that the risk of diarrhea among children whose mothers/caretakers had less knowledge on prevention methods of diarrhea was higher compared to children whose mothers/caretakers had knowledge on prevention methods of diarrhea. Finally, this finding is similar to other studies, which found that respondents with less knowledge on predisposing factors of diarrhea were more likely to have poor hand washing practice [50, 67]

Ethiopia has been implementing a community-level health intervention package (referred to as “Health Extension Program”) to improve the health of children in particular by deploying health extension workers. Of the 16 packages, seven involve hygiene and environmental sanitation (excreta, solid and liquid waste disposal, water supply, food hygiene, housing, personal hygiene, vector and rodent control) [32]. Risk of diarrhea in children was linked to the frequency of visits by health extension workers. For instance, households visited every 3 months were able to decrease diarrhea by 41 % compared to households visited one time in 6 months in this study. The frequency of visitation by health extension workers might have increased the implementation of health extension packages by households in the domain. There is evidence that childhood diarrhea reduced significantly among families in households that fully implemented basic health packages [13, 68].

The health risks from inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene have been documented previously [69]. There is also evidence that shows the risk reduction of diarrheal disease being associated with improvements in both water and sanitation [70]. Environmental fecal-oral pathogen load varied at different scenarios: pathogen load was low in areas having greater than 98 % of improved water supply and sanitation coverage, but high in areas with incomplete coverage of either improved water supply or sanitation and very high in areas practicing open defecation [71]. The provision of improved water supply was found to reduce the risk of childhood diarrhea by 40 % in this study, which is similar to other findings that stated that provision of improved water supply was found to be effective in diarrhea disease reduction, particularly the provision of piped water supply [51, 60].

Households with unimproved latrine and absence of latrine at the community level were found to increase childhood diarrhea by 49 and 75 %, respectively, compared to households with improved latrines in this study. A similar study indicated the risk of exposure to high level of pathogens from fecal material in households with improved sanitation from neighbors who have no improved sanitation [60]. A meta-analysis done in 2014 showed that the overall effect for access to an improved sanitation facility on reduction in diarrhea morbidity was 28 % (RR 0.72, 95 % CI 0.59–0.88) [70].

Community immunity protects unvaccinated children and adults by reducing the spread of transmission and has also been noted after routine rotavirus immunization [27, 72] and measles immunization in several countries. The study found that the risk of diarrhea among children who did not receive measles vaccine was nearly four times higher compared to children who received measles vaccine. This finding is in agreement with other studies [73–75], which found that the incidence of diarrhea was high during outbreak of measles.

Studies showed rotavirus as the most common cause of vaccine-preventable diarrheal disease during dry seasons [1, 23]. Childhood diarrhea among children who received rotavirus vaccine was also less compared to children who did not receive rotavirus vaccine. This finding is in line with other findings [23–29], which found that diarrhea episodes among children were reduced after implementation of this vaccine during dry season. This study was carried out during dry season from February 2015 to April 2015. Since 2014, Ethiopia has become one of the 49 eligible countries for funding by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) to begin universal rotavirus immunization [33].

Analyzing individual- and communal-level factors using a multilevel model which is very important to control unexplained variations of the higher level for preventing misleading associations is the strength of this study. One of the limitations of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the study, and it shares the drawbacks of similar cross-sectional studies. Underestimation of childhood diarrhea prevalence might be another limitation of this study since data were collected in the dry season (February to March). Comprehensive knowledge of diarrhea which include causes of diarrhea, means of transmission and methods of preventions of diarrhea, and hand washing practices used in the analysis were self-reported by the respondent; self-reported data have been found to introduce inaccuracy and bias into estimates of behavior [76].

Conclusions

The prevalence of childhood diarrhea remains high in the study area. The prevalence of childhood diarrhea did not show a statistically significant variation between high and low hotspot districts. Both individual- and communal-level factors play a significant role in the occurrence of childhood diarrhea, which accounted for 35 % variation across the communities. Age of child between 6 to 35 months, complementary feeding initiation below 6 months, inadequate hand washing practices, less knowledgeable mothers on prevention methods of diarrhea, poorest wealth status of households, and household revisit time above 6 months by health extension workers were the factors that increased the odds of childhood diarrhea at individual level, whereas lack of improved water supply and improved sanitation facilities and unvaccinated children with measles and rotavirus vaccine were the factors associated with childhood diarrhea at the community level.

Therefore, the reduction of childhood diarrhea requires combination of interventions at individual and community level: education of mothers on proper time of complementary feeding, causes of diarrhea, means of transmission and prevention methods of diarrhea, improved economic status of households, provision of improved drinking water supply and improved sanitation, increasing the coverage of measles and rotavirus vaccine.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- GAVI:

-

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization

- ICC:

-

intra-cluster correlation

- MOR:

-

median odds ratio

- PCV:

-

proportional change in variance

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–16.

Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–40.

WHO. Diarrheal Diseases. World Health Organization 2013.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128.

Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(2):136–41.

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey. Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2001. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Marco ,2001. Central Statistics Authority (Ethiopia) and ORC Macro; 2001.

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro, 2012. Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro; 2011.

Bbaale E. Determinants of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection among under-fives in Uganda. Australas Med J. 2011;4(7):400–9.

Omore R, O'Reilly CE, Williamson J, Moke F, Were V, Farag TH, et al. Health care-seeking behavior during childhood diarrheal illness: results of health care utilization and attitudes surveys of caretakers in western Kenya, 2007-2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(1 Suppl):29–40.

Diouf K, Tabatabai P, Rudolph J, Marx M. Diarrhoea prevalence in children under five years of age in rural Burundi: an assessment of social and behavioural factors at the household level. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24895.

Dessalegn M, Kumie A, Tefera W. Predictors of under five childhood Diarrhea: Mecha District, West Gojjam, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2011;25(3):192–200.

Eshete WB. A stepwise regression analysis on under-five diarrhoael morbidity prevalence in Nekemte town, western Ethiopia: maternal care giving and hygiene behavioral determinants. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5(3):193–8.

Gebru T, Taha M, Kassahun W. Risk factors of diarrhoeal disease in under-five children among health extension model and non-model families in Sheko District rural community, southwest Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:395.

Mengistie B, Berhane Y, Worku A. Prevalence of diarrhea and associated risk factors among children under-five years of age in Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Open J Prev Med. 2013;3(7):446–53.

Sinmegn Mihrete T, Asres Alemie G, Shimeka TA. Determinants of childhood diarrhea among underfive children in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, North West Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:102.

Teklemariam S, Getaneh T, Bekele F. Environmental determinants of diarrheal morbidity in under-five children, Keffa-Sheka zone, south west Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2000;38(1):27–34.

Woldemicael G. Diarrhoeal morbidity among young children in Eritrea: environmental and socioeconomic determinants. J Health Popul Nutr. 2001;19(2):83–90.

Godana W, Mengistie B. Determinants of acute diarrhoea among children under five years of age in Derashe District, Southern Ethiopia. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(2329):10.

Mekasha A, Tesfahun A. Determinants of diarrhoeal diseases: a community based study in urban south western Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(2):77–82.

Simiyu S. Water risk factors pre-disposing the under five children to diarrhoeal morbidity in Mandera District. Kenya East Afr J Public Health. 2010;7(4):353–60.

Prüss-Üstün ACC. Preventing disease through health environments towards an estimate of the environmental burden of disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 2006.

Lamberti LM, Fischer Walker CL, Black RE. Systematic review of diarrhea duration and severity in children and adults in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:276.

Enweronu-Laryea CC, Boamah I, Sifah E, Diamenu SK, Armah G. Decline in severe diarrhea hospitalizations after the introduction of rotavirus vaccination in Ghana: a prevalence study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:431.

Fernandes EG, Sato HK, Leshem E, Flannery B, Konstantyner TC, Veras MA, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrhea-related hospitalizations in Sao Paulo State. Brazil Vaccine. 2014;32(27):3402–8.

do Carmo GM, Yen C, Cortes J, Siqueira AA, de Oliveira WK, Cortez-Escalante JJ, et al. Decline in diarrhea mortality and admissions after routine childhood rotavirus immunization in Brazil: a time-series analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8(4):e1001024.

Desai R, Oliveira LH, Parashar UD, Lopman B, Tate JE, Patel MM. Reduction in morbidity and mortality from childhood diarrhoeal disease after species A rotavirus vaccine introduction in Latin America—a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(8):907–11.

Dennehy PH. Effects of vaccine on rotavirus disease in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24(1):76–84.

Becker-Dreps S, Melendez M, Liu L, Zambrana LE, Paniagua M, Weber DJ, et al. Community diarrhea incidence before and after rotavirus vaccine introduction in Nicaragua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(2):246–50.

Chang MR, Velapatino G, Campos M, Chea-Woo E, Baiocchi N, Cleary TG, et al. Rotavirus seasonal distribution and prevalence before and after the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in a peri-urban community of Lima. Peru Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(5):986–8.

UNICEF and World Health Organization. Progress on sanitation and drinking-water - 2015 update and MDG assessment. 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2015.

Baker SM, Ensink JH. Helminth transmission in simple pit latrines. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(11):709–10.

Ministry of Health. Health Sector Development Plan, 2005/6-2010/11, Mid-Term Review. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2008.

Alliance G. WHO, MOH, UNICEF. Millions of Ethiopian children to be protected each year against leading cause of severe diarrhoea. 2013.

Amhara Regional State Health Bureau. Annual Report, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Amhara Regional State Health Bureau 2011/12.

Guo G, Zhao H. Multilevel modeling for binary data. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:441–62.

Azage M, Kumie A, Worku A, Bagtzoglou AC. Childhood diarrhea exhibits spatiotemporal variation in northwest Ethiopia: a SaTScan spatial statistical analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144690.

UNICEF/WHO. Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. World Health Organization; 2009.

Rosinski A, Narine S, Yamey G. Developing a scorecard to assess global progress in scaling up diarrhea control tools: a qualitative study of academic leaders and implementers. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67320. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067320.

Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MT. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(1):224–7.

Halonen JI, Kivimaki M, Pentti J, Kawachi I, Virtanen M, Martikainen P, et al. Quantifying neighbourhood socioeconomic effects in clustering of behaviour-related risk factors: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32937.

Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(1):81–8.

Merlo J, Chaix B, Yang M, Lynch J, Rastam L. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: linking the statistical concept of clustering to the idea of contextual phenomenon. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):443–9.

Merlo J, Yang M, Chaix B, Lynch J, Rastam L. A brief conceptual tutorial on multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: investigating contextual phenomena in different groups of people. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(9):729–36.

Das JK, Salam RA, Bhutta ZA. Global burden of childhood diarrhea and interventions. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27(5):451–8.

Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(1):77–82.

Gupta A, Sarker G, Rout A, Mondal T, Pal R. Risk correlates of diarrhea in children under 5 years of age in slums of Bankura, West Bengal. J Global Infect Dis. 2015;7(1):23–9.

Mock NB, Sellers TA, Abdoh AA, Franklin RR. Socioeconomic, environmental, demographic and behavioral factors associated with occurrence of diarrhea in young children in the Republic of Congo. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):807–16.

Getaneh T, Assefa A, Tadesse Z. Diarrhoea morbidity in an urban area of southwest Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1997;74(8):491–4.

El-Gilany AH, Hammad S. Epidemiology of diarrhoeal diseases among children under age 5 years in Dakahlia, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(4):762–75.

Mashoto KO, Malebo HM, Msisiri E, Peter E. Prevalence, one week incidence and knowledge on causes of diarrhea: household survey of under-fives and adults in Mkuranga district, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:985.

Siziya S, Muula AS, Rudatsikira E. Diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections prevalence and risk factors among under-five children in Iraq in 2000. Ital J Pediatr. 2009;35(1):8.

Pickering AJ, Julian TR, Marks SJ, Mattioli MC, Boehm AB, Schwab KJ, et al. Fecal contamination and diarrheal pathogens on surfaces and in soils among Tanzanian households with and without improved sanitation. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(11):5736–43.

Mattioli MC, Pickering AJ, Gilsdorf RJ, Davis J, Boehm AB. Hands and water as vectors of diarrheal pathogens in Bagamoyo, Tanzania. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(1):355–63.

Ehiri JE, Azubuike MC, Ubbaonu CN, Anyanwu EC, Ibe KM, Ogbonna MO. Critical control points of complementary food preparation and handling in eastern Nigeria. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(5):423–33.

Motarjemi Y, Kaferstein F, Moy G, Quevedo F. Contaminated weaning food: a major risk factor for diarrhoea and associated malnutrition. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71(1):79–92.

Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e837–42.

Ehlayel MS, Bener A, Abdulrahman HM. Protective effect of breastfeeding on diarrhea among children in a rapidly growing newly developed society. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51(6):527–33.

Ahiadeke C. Breast-feeding, diarrhoea and sanitation as components of infant and child health: a study of large scale survey data from Ghana and Nigeria. J Biosoc Sci. 2000;32(1):47–61.

WHO. World Health Organization guidelines approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Kwasi Owusu B, Markku K. Childhood diarrheal morbidity in the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana: socio-economic, environmental and behavioral risk determinants. World Health & Population; 2005. doi:10.12927/whp.2005.17646. [Avilable at: http://healthcarepapers.com/content/17646, Accessed Oct 2015].

Avachat SS, Phalke VD, Phalke DB, Aarif SM, Kalakoti P. A cross-sectional study of socio-demographic determinants of recurrent diarrhoea among children under five of rural area of Western Maharashtra, India. Australas Med J. 2011;4(2):72–5.

Begum HA, Moneesha SS, Sayem AM. Child care hygiene practices of women migrating from rural to urban areas of bangladesh. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2013;25(4):345–55.

Halder AK, Tronchet C, Akhter S, Bhuiya A, Johnston R, Luby SP. Observed hand cleanliness and other measures of handwashing behavior in rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:545.

George CM, Perin J, de Calani Neiswender KJ, Norman WR, Perry H, Davis Jr TP, et al. Risk factors for diarrhea in children under five years of age residing in peri-urban communities in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(6):1190–6.

Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billhimer W, Altaf A, et al. Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):225–33.

Luby SP, Halder AK, Huda T, Unicomb L, Johnston RB. The effect of handwashing at recommended times with water alone and with soap on child diarrhea in rural Bangladesh: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(6):e1001052.

Mwambete KD, Joseph R. Knowledge and perception of mothers and caregivers on childhood diarrhoea and its management in Temeke municipality, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2010;12(1):47–54.

Berhe F, Berhane Y. Under five diarrhea among model household and non model households in Hawassa, South Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional community based survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:187.

Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford Jr JM. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(1):42–52.

Wolf J, Pruss-Ustun A, Cumming O, Bartram J, Bonjour S, Cairncross S, et al. Assessing the impact of drinking water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and middle-income settings: systematic review and meta-regression. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(8):928–42.

Prüss A, Kay D, Fewtrell L, Bartram J. Estimating the burden of disease from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(5):537–42.

Lopman BA, Curns AT, Yen C, Parashar UD. Infant rotavirus vaccination may provide indirect protection to older children and adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(7):980–6.

Sniadack DH, Moscoso B, Aguilar R, Heath J, Bellini W, Chiu MC. Measles epidemiology and outbreak response immunization in a rural community in Peru. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77(7):545–52.

Feachem RG, Koblinsky MA. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: measles immunization. Bull World Health Organ. 1983;61(4):641–52.

Das SK, Faruque AS, Chisti MJ, Malek MA, Salam MA, Sack DA. Changing trend of persistent diarrhoea in young children over two decades: observations from a large diarrhoeal disease hospital in Bangladesh. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(10):e452–7.

Curtis V, Cousens S, Mertens T, Traore E, Kanki B, Diallo I. Structured observations of hygiene behaviours in Burkina Faso: validity, variability, and utility. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71(1):23–32.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Addis Ababa University, Bahir Dar University, the University of Connecticut, and USAID for their financial and technical support to do this research project. We would like to thank the study participants, supervisors of the study, and Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau, Zonal Health and District Health offices for their cooperation during data collection and facilitation to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MA was involved in proposal development, data collection, data management, analysis, and write-up of the article. AK, AW, and AB were involved in proposal development, data analysis, and writing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Additional file on results of high and low hotspot districts in the study area. (XLS 31 kb)

Additional file 2:

Questionnaire (English_version) (DOC 238 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Azage, M., Kumie, A., Worku, A. et al. Childhood diarrhea in high and low hotspot districts of Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia: a multilevel modeling. J Health Popul Nutr 35, 13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-016-0052-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-016-0052-2