Abstract

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a lethal pediatric brain tumor and the leading cause of brain tumor–related death in children. As several clinical trials over the past few decades have led to no significant improvements in outcome, the current standard of care remains fractionated focal radiation. Due to the recent increase in stereotactic biopsies, tumor tissue availabilities have enabled our advancement of the genomic and molecular characterization of this lethal cancer. Several groups have identified key histone gene mutations, genetic drivers, and methylation changes in DIPG, providing us with new insights into DIPG tumorigenesis. Subsequently, there has been increased development of in vitro and in vivo models of DIPG which have the capacity to unveil novel therapies and strategies for drug delivery. This review outlines the clinical characteristics, genetic landscape, models, and current treatments and hopes to shed light on novel therapeutic avenues and challenges that remain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a lethal malignant pediatric tumor that grows diffusely in the pons. This devastating disease has a median age at diagnosis of 6–7 years and is seldom identified in adults. Given its eloquent location, current treatment options are limited and prognosis is dismal—with less than 10% of patients surviving beyond 2 years from the time of diagnosis [1]. DIPGs represent 80% of all pediatric brain tumors that occur in the brainstem [2, 3]. Histologically, these tumors share features with anaplastic astrocytomas (grade III) or glioblastomas (GBM) (grade IV) [4]. Under the World Health Organization 2016 classification of brain tumors, pediatric gliomas with a K27M mutation in histone H3 (3.1 or 3.3) with a diffuse growth pattern in a midline location are termed diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M mutant; this designation is inclusive of DIPG cases bearing the K27M mutation [4].

In recent years, significant advancements have been made in our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of these tumors. Previously, pediatric high-grade gliomas (HGG) were thought to resemble adult HGG and were clinically managed as such [5]. However, it is now appreciated that distinct molecular alterations distinguish DIPG from their adult HGG counterparts [6]. This review will present a brief overview of DIPG including its presentation, classification, and treatment options. We also summarize current research and future directions.

Clinical presentation and diagnostic considerations

Patients with DIPG can present with a wide variety of neurological symptoms reflective of the anatomic localization of the lesion. Thus, in over 50% of patients, cranial nerve palsies (facial asymmetry and diplopia), long tract signs (hyperreflexia, upgoing Babinski), and cerebellar signs (ataxia, dysmetria) are present [7, 8]. Together, these three frequently occurring clinical characteristics are referred to as the “classic triad” and should raise clinical suspicion of this diagnosis prompting appropriate diagnostic imaging. Given that DIPG progresses rapidly, children typically manifest symptoms for a month or less before coming to clinical attention [9]. Cranial nerves VI and VII are the most commonly affected and specific dysfunction of these is characteristic of DIPG [8]. Furthermore, while obstructive hydrocephalus with elevated intracranial pressure is observed in less than 10% of patients at the time of diagnosis, the condition is commonly noted in patients reaching the end-stage of their disease [10].

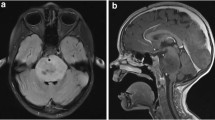

Classically the diagnosis of DIPG has been made based on clinical presentation and neuroimaging findings alone. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis, though on occasion computed tomography (CT) may also be used [11]. Due to the infiltrative nature of these tumors, DIPGs demonstrate T1-hypointensity with ill-defined margins and hyperintensity on T2 weighted images—generally without contrast enhancement (Fig. 1) [8, 12]. Gadolinium enhancement may be of value in confirming the diagnosis or in ruling out other lesions. On imaging, the tumor core is centered in the pons and at the time of presentation can occupy greater than 50% of its axial diameter, typically engulfing the basilar artery. Although DIPGs grow infiltratively and diffusely along fiber tracts to adjacent locations such as the thalamus and cerebellum, they rarely metastasize to distant sites [13].

T2-weighted sagittal pediatric brain MRI. Characteristic diagnostic T2-weighted MRI of pediatric DIPG. Note brainstem which demonstrates a diffuse expansile hyperintense lesion in the pons (arrow). These tumors are surgically unresectable due to their poorly circumscribed border and highly eloquent location. Where safe-entry zones are obeyed and neuromonitoring is employed, incisional biopsies under direct observation can be performed

Historically, advances in imaging techniques rendered biopsies unnecessary to establish a diagnosis in the case of typically presenting DIPGs [14]. This, combined with the perceived risk of obtaining tumor tissue from the eloquent brainstem, has resulted in a relative lack of availability of DIPG samples worldwide to support basic science research. However, with the growing role of molecular diagnostics in DIPG, the relevance and safety of brainstem biopsies have helped move the field forward [15, 16]. A number of studies have shown that biopsies can be performed safely [17,18,19] and many centers have begun to use stereotactic biopsy as standard practice in an effort to enhance diagnosis and support basic science research and as a gateway for entry into ongoing clinical trials which require histological and molecular data [15, 16, 20, 21]. Our own tertiary pediatric care center also advocates for this approach. Although currently limited, the acquisition of tumor tissue which yields insights into the molecular phenotypes of this heterogeneous disease will provide physicians with significant insights into diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of children.

Differential diagnostic considerations include non-malignant brainstem entities including low-grade glioma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), vascular malformations, encephalitic parenchymal lesions, cysts, and demyelinating disorders [22, 23]. When tissue is available through biopsy, the diagnosis can be confirmed by histological review, supplemented by molecular testing where available. Microscopically, cases often show high-grade astrocytic histology, with findings of increased mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and/or necrosis (Fig. 2) [10]. A smaller percentage of cases however will show lower grade histology with overall bland cytology lacking some or all the traditional high-grade features. In addition to typical glioma immunohistochemistry panels such as GFAP, ATRX, p53, neurofilament, ki-67 immunostains, targeted antibodies for H3K27M, BRAF-V600E, and IDH1-R132H may be applied (Fig. 2 b and c). Various molecular pathology approaches including next-generation sequencing and DNA microarrays are utilized to molecularly confirm the presence or absence of a histone 3 (H3) mutation and identify the histone isoform affected given their prognostic differences. Although therapeutically relevant mutations such as BRAF-V600E are quite rare in DIPG tumors [24], evaluation is generally attempted given the availability of targeted therapies such as dabrafenib or vemurafenib [25]. A useful summary of clinicopathologic features of DIPG can be found in Table 1.

Representative histology of pediatric DIPG. a Hematoxylin & eosin stain of pediatric DIPG acquired post-mortem, note diffusely infiltrative tumor cells amidst a background matrix of neuropil. b Immunohistochemical staining of the same sample using antibody directed to the H3K27M epitope. The sample is strongly positive. c Immunohistochemical staining of mutant p53, a common co-occurring mutation in DIPG. Note sparser staining than H3K27M in panel b

Molecular characteristics and subgroups

DIPGs can be sub-classified into 3 distinct molecularly defined groups: H3K27M, MYCN, and silent [26]. Previous research has identified that while DIPGs do share similarities with supratentorial HGG, it remains a unique entity with distinct genomic and molecular alterations [27]. For example, H3 mutations are identified in nearly 80% of DIPGs whereas only 35% of pediatric non-brainstem high-grade gliomas have H3 mutations [27]. Although many hallmark mutations have been identified in DIPG, it is important to note that intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity has been documented in this disease [28].

Histone mutations are present in the majority of DIPG tumors, and the identification of these mutations has resulted in a paradigm shift that has redefined our focus of research and clinical management [29, 30]. The histone mutation H3K27M results in the substitution of lysine with methionine in the isoforms H3.1 and H3.3, encoded by genes HIST1H3B and H3F3A respectively. This mutation leads to the loss of histone trimethylation via inhibition of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), ultimately producing epigenetic silencing [29, 31]. However, despite extensive modeling using in vivo mouse models, the precise role of H3K27M in tumor initiation remains elusive [32].

There are subtle differences between the histone mutations in H3.1 and H3.3, particularly regarding survival, phenotype, and clinical outcomes [30, 31]. H3.1 histone mutations tend to be associated with slightly improved survival and reduced presence of metastasis [33]. Overall, in comparison with other H3 wild-type cases, the H3K27M is associated with significantly worse outcomes irrespective of the isoform affected [34].

ACVR1 mutations have been identified in approximately 30% of DIPG tumors, and co-segregate with H3.1 [26, 27, 35]. It has been previously shown that ACVR1 mutation facilitates early tumor progression coupled with other molecular aberrations, and shows promise for therapeutic targeting [36]. TP53 mutations have been identified in approximately 22–40% of DIPGs and often co-occur with PDGFR amplification [37, 38]. TP53 mutation, coupled with H3.3K27M and typically PPM1D mutations have been demonstrated to allow tumor cells to evade cell death and senescence by influencing epigenetic regulation [39].

PDGFRA is the most commonly observed amplification, present in approximately one-third of high-grade gliomas and is implicated in the RTK-RAS-PI3K-Akt signaling pathway [40]. PDGFRA causes activation of PI3K and MAPK pathways via phosphorylation at various phosphotyrosine domains [40]. Amplifications of PDGFRA co-segregate with histone H3.3 mutations and are clinically aggressive regardless of histological classifications [30, 31, 38].

In addition to PDGFRA, PIK3R1 and PIK3CA are also drivers of the PI3K pathway and have been found to contribute to an aggressive phenotype in DIPG [28, 37]. These mutations have been characterized as an obligatory partner in H3.3K27M and are reported in clonal populations of DIPG. Lastly, MYC and MYCN aberrations are present in DIPGs and act as transcriptional regulators that enhance gene expression genome-wide [27]. Further investigation of the genomic landscape and the biological underpinnings of this disease is prudent to characterize important oncogenic drivers/pathways and subsequent actionable targets [27]

Treatment challenges and obstacles to progress

The current standard of care for DIPGs consists of standard fractionated radiation alone to a dose of 54–59 Gy, as any chances of meaningful surgical resection are limited by the eloquent location of DIPGs [41]. Furthermore, many treatment regimens, including monotherapy and combination chemotherapies have thus far yielded no substantial benefit [5, 42, 43]. Recent advances in the field of immunotherapy however have identified a potential role for anti-GD2 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which may show potential efficacy [44]. These limited treatment options highlight the need for novel therapeutic approaches. Herein we describe possible targets and common obstacles to effective therapies.

A variety of oncogenic drivers and somatic mutations in DIPG contribute to its rapid tumorigenesis and dismal outcomes. As previously mentioned, the most common mutation involves the substitution of a lysine for methionine at position 27 in histone H3, particularly in histone 3.1 and 3.3, which is associated with a worse prognosis over their wild-type counterparts [30, 45, 46]. DIPGs tend to have either a somatic mutation in H3K27M and/or a global loss of H3K27 trimethylation; as such, this is suggested to be one of the oncogenic drivers of this disease [31]. The presence of H3K27M leads to various downstream chromatin remodeling cascades, epigenetic silencing, and activation of various genes and pathways [47, 48]. The identification of this mutation and discoveries of subsequent secondary mutations open the door to druggable targets such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) and demethylase inhibitors—some of which have shown promising results [34, 49, 50]. Studies have also found that targeting transcriptional regulators via activation of bromodomain proteins has been effective in preclinical models [49, 51]. Although many DIPGs occur with the histone mutation, many targetable secondary mutations have also been identified that play a role in tumorigenesis [26, 35, 45, 52].

Previously, one of the most common obstacles regarding DIPG research and target identification was the lack of available tumor tissue. However, with increasing acquisition of post-mortem tissues and biopsies, several molecular studies can now be performed robustly and reproducibly. As a result, many promising targets have been identified and several drugs have shown efficacy in the preclinical setting. However, there remains a considerable obstacle between clinical application and drug discovery due to the lack of effective drug delivery across an intact blood-brain barrier (BBB). This may also explain why drugs that show efficacy in other gliomas have failed in DIPG [53]. Improving drug delivery, as a result of structural adaptation or physical disruption of the BBB will be vital for novel therapies to be translated into the clinic.

Lastly, the tumor microenvironment is a critical component of the tumor to consider when deciding treatment, particularly immunotherapy. Recent studies have concluded that DIPGs possess a non-inflammatory tumor microenvironment [54, 55]. However, whether DIPG tumors contain tumor-associated macrophages has yet to be fully investigated as there are conflicting results that state DIPGs do not have increased macrophage infiltration [54] or that DIPGs have increased macrophage infiltration but do not secrete inflammatory cytokines [55]. That said, most studies demonstrate that there is no T-cell infiltration in DIPG, and thus immunotherapeutic approaches should be focused on the recruitment or introduction of immune cells to the tumor.

Experimental models of DIPGs

The rare occurrence and eloquent location of DIPG make it difficult to obtain comprehensive tumor tissue that accurately reflects the intratumoral heterogeneity of this disease. Thus, more so than in other cancers, the establishment of biologically representative models is critical in revealing its genomic and epigenomic underpinnings. Patient-derived cell lines from biopsy and post-mortem tissue have allowed experiments in vitro that elucidate many targets and functional pathways [56]. Most groups have either utilized neurosphere [34, 57,58,59] or adherent monolayer patient-derived cell cultures [53, 60,61,62] for in vitro testing of novel drugs and targets. Historically, glioma cells have been cultured as adherent monolayers in the presence of fetal bovine serum (FBS); recently, however, 3-dimensional serum-free culture methods have become increasingly popular for in vitro drug testing. Moreover, recent research has demonstrated that culture conditions including culture media components and oxygen concentrations in the culture environment can cause major changes in gene expression, pathway activation and subsequently influence the validity of in vitro response to therapies [63, 64].

The first attempts to develop animal models of DIPG involved intracranial injections of rat glioma cell lines into the brainstem of neonatal and adult rats in order to recapitulate brainstem gliomas [65,66,67,68]. Although these models did faithfully produce tumors resembling gliomas in the appropriate location, one major criticism of this approach is that the tumor cells are derived from gliomas that arose in the cerebral cortex which biologically differ from gliomas which arise in the brainstem [10]. Several groups have also generated xenograft models either from human adult hemispheric GBM derived cells or from established GBM cell lines by serial transplantation of xenografts into the brainstem of immunodeficient rats or mice [69,70,71]. However, the caveat with this model is that the use of glioma cells from the cerebrum, which regardless of growing in the brainstem microenvironment, may not adequately recapitulate DIPG. In an effort to address the challenges mentioned, Monje and colleagues were the first to develop DIPG-specific cell and xenograft lines from post-mortem tissue [39]. Since then, tissues harvested from living biopsies are beginning to emerge, as groups have developed DIPG cell lines from tumor samples harvested at diagnosis [62, 72].

In addition to human xenograft mouse models, genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) have proven useful for the elucidation of genetic alterations, oncogenic drivers, and lineages of clones in tumor cells in immune-competent models [73]. These GEMMs have the advantage of being immune competent and are therefore useful for pre-clinical trials of immunotherapeutic approaches. Furthermore, they are far more accurate in recapitulating the tumor microenvironment in comparison to xenograft models [74]. Earlier GEMMs were generated using the replication-competent avian sarcoma-leucosis virus (RCAS) vector to enable Ink4a-ARF loss and platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB) overexpression within nestin-expressing cells in the pons of genetically engineered pups expressing tumor virus A (TVA) under the nestin promoter [75, 76]. Although, these attempts created successful infiltrative tumors, they were not exclusive to the pons [77, 78]. More recent models of DIPG GEMMs have utilized specific genetic alterations such as PDGFB, H3K27M, and p53 [79] although these models are also not exclusive to the pons. Recently, models of ACVR1 have elucidated that mutant ACVR1 arrests glial cell differentiation and subsequently drives tumorigenesis in pediatric gliomas [80]. In the future, the development of faithful genetic models of DIPGs that consistently recapitulate both spatiotemporal and molecular tumor characteristics will be vital for identifying novel oncogenic programs and elucidating the temporal and spatial factors which contribute to tumor formation.

Novel therapeutic avenues

There are multiple therapeutic avenues for DIPG that hold promise for the future. These include targeted therapies, epigenetic therapy, and immunotherapy. Here, we briefly describe each of these avenues and highlight their current state of development and their significance.

Since the development of targeted therapies for DIPG, approximately 250 clinical trials have been initiated against different biological pathways in the disease [81]. One of the most frequently amplified genes is PDGFRA which is found in 10% of DIPGs. As a result, PDGFRA is one of the most targeted genes for therapy in DIPG [38, 82]. However, agents that target PDGFR such as imatinib and dasatinib have exhibited fairly poor antitumor effects in clinical trials [62]. Another gene that has been targeted in DIPG is EGFR, which has also been shown to be overexpressed in pediatric brain tumors [83]. Clinical trials of anti-EGFR drugs including nimotuzumab, gefitinib, and erlotinib have shown some benefit in small subsets of DIPG patients [84,85,86]. Other trials have used PARP1 inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib, veliparib), CDK4/CDK6 inhibitors (PD-0332991), WEE1 kinase inhibitor (MK1775), and the angiogenesis inhibitor (bevacizumab) [87,88,89]. Despite various clinical trial attempts, none of these has shown significant efficacy in DIPG. One of the rate-limiting steps in these clinical trials is incomplete knowledge of whether these agents cross the BBB [53].

Recently, substantial evidence has suggested that epigenetic alterations, coupled with genetic mutations, are responsible for tumorigenesis. Studies using JMJD3 inhibitors such as panobinostat and GSK-4, which target histone deacetylase and demethylase, respectively, have shown promising results and at present have moved into clinical trials as both single and combination agents (Fig. 3 a and b) [34, 90, 91]. The decreased H3K27me3 levels have led to unique strategies that target chromatin remodelers. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is a H3K27-methylating enzyme and was found to be highly expressed in H3K27M-mutant DIPG [92]. However, treatment with the EZH2 inhibitor, EPZ6438, has yielded little to no results in both GBM and DIPG cell lines [93]. In contrast, tazemetostat (Fig. 3c) which is also an EZH2 inhibitor has yielded significantly better results, although this may be due to sample selection bias [94]. On the other hand, studies have also targeted enzymes responsible for demethylation of H3K27 such as JMJD3 [95]. Transcriptional regulators such as BET family proteins have also been investigated as targeted for therapy in brain tumors. JQ1 has been found to be a histone-binding module inhibitor that binds to the bromodomains and displaces the BRD4 fusion oncoproteins subsequently leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Fig. 4a) [96]. In addition, alternatives methods of disrupting transcription have also been effective such as CDK7 inhibition with THZ1 (Fig. 4b) [51]. Apart from these molecular targets, several other secondary mutations have yet to be investigated as therapeutically actionable (Table 2).

Drug targets and treatments of pediatric DIPG. DIPGs are characterized by the K27M mutation that occurs in histone H3. Therapies which target the epigenome including histone deacetylase inhibitors such as panobinostat (a) and histone demethylase inhibitors such as GSK-J4 (b) have been demonstrated to be effective in clinical trials. Furthermore, residual PRC2 activity has been shown to be required for proliferation and thus EZH2 inhibitors such as tazemetostat (c) has been effective in treating these tumors

Targetable transcriptional dependencies in DIPGs. DIPGs can also be targeted pharmacologically at the DNA level by leveraging the transcriptional dependencies of the tumor. Transcriptional disruption has been demonstrated to reduce tumor growth via bromodomain (a) or CDK7 (b) inhibition using JQ1 or THZ1, respectively

Emerging evidence has linked epigenetics and metabolomics to plasticity and intratumor heterogeneity in brain tumors [97,98,99,100]. Specifically in DIPGs, recent studies have found that metabolic reprogramming contributes to the pathogenesis of H3.3K27M DIPGs, primarily by utilizing alpha-ketoglutarate to maintain a preferred epigenetic state of low H3K27me3 [97]. Furthermore, they also show that H3.3K27M cells show intratumoral heterogeneity in their usage of glucose or glutamine to regulate global H3K27me3 with dependence on one or both pathways [97]. In return, the metabolic regulation of global H3K27me3 leads to heterogeneous dependencies on glutamate dehydrogenase, hexokinase 2, and wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), which are possible therapeutic targets. Leveraging these metabolic and epigenetic vulnerabilities in DIPG should be a priority for future treatment strategies.

Immunotherapy is rapidly establishing itself as a pillar of cancer therapy, and recent studies have demonstrated its potential in brain tumors [101,102,103,104,105]. In particular, an anti-GD2 CAR-T study portrayed positive results in DIPG in vivo models [44]. However, it is important to note that the administration of these GD2 CARs had resulted in hydrocephalus that was lethal in a subset of animals which was suggested to be due to the neuroanatomical location of the tumors to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways [44]. Given these challenges, the need for identification of novel strategies in administrating immunotherapy will be required to advance this promising treatment into clinical trials.

Conclusion

The elaborate molecular pathogenesis, strict BBB regulation, and eloquent location have contributed to the current lack of improvements in prognosis for DIPG. Radiation therapy remains the mainstay of care. However, with an increasing understanding of its molecular genetics, a growing number of promising preclinical models, and novel techniques to overcome the limitations of effective drug delivery across the BBB, it is our hope that the future of DIPG therapy will change dramatically in a relatively short time, much to the benefit of children who harbor this devastating brain tumor.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- DIPG:

-

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- HGG:

-

High-grade glioma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PNET:

-

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- PRC2:

-

Polycomb repressive complex 2

- ACVR1:

-

Activin A receptor, type I

- PDGFR:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PPM1D:

-

Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent 1D

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- CAR:

-

Chimeric antigen receptor

- PI3K:

-

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases

- HDAC:

-

Histone deacetylase

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- BBB:

-

Blood-brain barrier

- GEMM:

-

Genetically engineered mouse models

- RCAS:

-

Replication-competent avian sarcoma-leukosis virus

- TVA:

-

Tumor virus A

- PDGFB:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor B

- PDGFRA:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor A

- EZH2:

-

Enhancer of zeste 2

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- CDK4/6:

-

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6

- PARP1:

-

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

- MJD3:

-

Jumonji domain-containing protein D3

- BRD4:

-

Bromodomain-containing protein 4

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- IDH1:

-

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1

References

Warren KE. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: poised for progress. Front Oncol. 2012;2:1–9.

Hargrave D, Bartels U, Bouffet E. Diffuse brainstem glioma in children: critical review of clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2006 Mar;7(3):241–8.

Duffner PK, Cohen ME, Freeman AI. Pediatric brain tumors: an overview. CA Cancer J Clin. 1985/09/01. 1985;35(5):287–301.

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–20.

Vanan MI, Eisenstat DD. DIPG in Children - What Can We Learn from the Past?. Frontiers in oncology, 2015;5:237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2015.00237.

Schroeder KM, Hoeman CM, Becher OJ. Children are not just little adults: Recent advances in understanding of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma biology. Pediatric Research. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2014;75:205.

Albright AL, Guthkelch AN, Packer RJ, Price RA, Rourke LB. Prognostic factors in pediatric brain-stem gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1986;65(6):751–5.

Fisher PG, Breiter SN, Carson BS, Wharam MD, Williams JA, Weingart JD, et al. A clinicopathologic reappraisal brain stem tumor classification: Identification of pilocytic astrocytoma and fibrillary astrocytoma as distinct entities. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1569–76.

Donaldson SS, Laningham F, Fisher PG. Advances toward an understanding of brainstem gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1266–72.

Yoshimura J, Onda K, Tanaka R, Takahashi H. Clinicopathological study of diffuse type brainstem gliomas: Analysis of 40 autopsy cases. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003;43(8):375–82.

Epstein F, Constantini S. Practical decisions in the treatment of pediatric brain stem tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;24(1):24–34.

Freeman CR, Farmer JP. Pediatric brain stem gliomas: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40(2):265–71.

Gururangan S, McLaughlin CA, Brashears J, Watral MA, Provenzale J, Coleman RE, et al. Incidence and patterns of neuraxis metastases in children with diffuse pontine glioma. J Neurooncol. 2006;77(2):207–12.

Walker DA, Liu JF, Kieran M, Jabado N, Picton S, Packer R, et al. A multi-disciplinary consensus statement concerning surgical approaches to low-grade, high-grade astrocytomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas in childhood (CPN Paris 2011) using the Delphi method. Neuro-Oncol. 2013;15(4):462–8.

Hamisch C, Kickingereder P, Fischer M, Simon T, Ruge MI. Update on the diagnostic value and safety of stereotactic biopsy for pediatric brainstem tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 735 cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;20(3):261–8.

Williams JR, Young CC, Vitanza NA, McGrath M, Feroze AH, Browd SR, et al. Progress in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: advocating for stereotactic biopsy in the standard of care. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;48(1):E4.

Pincus DW, Richter EO, Yachnis AT, Bennett J, Bhatti MT, Smith A. Brainstem stereotactic biopsy sampling in children. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(2):108–14.

Puget S, Beccaria K, Blauwblomme T, Roujeau T, James S, Grill J, et al. Biopsy in a series of 130 pediatric diffuse intrinsic Pontine gliomas. Childs Nerv Syst ChNS Off J Int Soc Pediatr Neurosurg. 2015;31(10):1773–80.

Roujeau T, Machado G, Garnett MR, Miquel C, Puget S, Geoerger B, et al. Stereotactic biopsy of diffuse pontine lesions in children. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(1):1–4.

Dawes W, Marcus HJ, Tisdall M, Aquilina K. Robot-assisted stereotactic brainstem biopsy in children: prospective cohort study. J Robot Surg. 2019;13(4):575–9.

Janjua MB, Ban VS, El Ahmadieh TY, Hwang SW, Samdani AF, Price AV, et al. Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas: Diagnostic approach and treatment strategies. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas. 201;72:15-19.

Friedrich C, Warmuth-Metz M, von Bueren AO, Nowak J, Bison B, von Hoff K, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the brainstem in children treated according to the HIT trials: clinical findings of a rare disease. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(3):227–35.

Schumacher M, Schulte-Mönting J, Stoeter P, Warmuth-Metz M, Solymosi L. Magnetic resonance imaging compared with biopsy in the diagnosis of brainstem diseases of childhood: a multicenter review. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(2):111–9.

Roux A, Pallud J, Saffroy R, Edjlali-Goujon M, Debily M-A, Boddaert N, et al. High-grade gliomas in adolescents and young adults highlight histomolecular differences with their adult and paediatric counterparts. Neuro-Oncol. 2020;8:1190-202.

Toll SA, Tran HN, Cotter J, Judkins AR, Tamrazi B, Biegel JA, et al. Sustained response of three pediatric BRAF V600E mutated high-grade gliomas to combined BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy. Oncotarget. 2019;10(4):551–7.

Buczkowicz P, Hoeman C, Rakopoulos P, Pajovic S, Letourneau L, Dzamba M, et al. Genomic analysis of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas identifies three molecular subgroups and recurrent activating ACVR1 mutations. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):451–6.

Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, Rankin SL, Ju B, Li Y, et al. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):444–50.

Hoffman LM, DeWire M, Ryall S, Buczkowicz P, Leach J, Miles L, et al. Spatial genomic heterogeneity in diffuse intrinsic pontine and midline high-grade glioma: implications for diagnostic biopsy and targeted therapeutics. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:1.

Lewis PW, Müller MM, Koletsky MS, Cordero F, Lin S, Banaszynski LA, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science. 2013;340(6134):857–61.

Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM, Bouffet E, et al. K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2012/06/05. 2012;124(3):439–47.

Castel D, Philippe C, Calmon R, Le Dret L, Truffaux N, Boddaert N, et al. Histone H3F3A and HIST1H3B K27M mutations define two subgroups of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas with different prognosis and phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2015;130(6):815–27.

Funato K, Major T, Lewis PW, Allis CD, Tabar V. Use of human embryonic stem cells to model pediatric gliomas with H3.3K27M histone mutation. Science. 2014;346(6216):1529–33.

Jones C, Baker SJ. Unique genetic and epigenetic mechanisms driving paediatric diffuse high-grade glioma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014/09/19 ed. 2014;14(10):651–61.

Grasso CS, Tang Y, Truffaux N, Berlow NE, Liu L, Debily MA, et al. Functionally defined therapeutic targets in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Nat Med. 2015;21(6):555–9.

Taylor KR, Mackay A, Truffaux N, Butterfield YS, Morozova O, Philippe C, et al. Recurrent activating ACVR1 mutations in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):457–61.

Buczkowicz P, Hawkins C. Pathology, molecular genetics, and epigenetics of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:1–9.

Grill J, Puget S, Andreiuolo F, Philippe C, MacConaill L, Kieran MW. Critical oncogenic mutations in newly diagnosed pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(4):489–91.

Puget S, Philippe C, Bax DA, Job B, Varlet P, Junier MP, et al. Mesenchymal transition and pdgfra amplification/mutation are key distinct oncogenic events in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):1-14.

Monje M, Mitra SS, Freret ME, Raveh TB, Kim J, Masek M, et al. Hedgehog-responsive candidate cell of origin for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(11):4453–8.

Paugh BS, Zhu X, Qu C, Endersby R, Diaz AK, Zhang JJ, et al. Novel oncogenic PDGFRA mutations in pediatric high-grade gliomas. Cancer Res. 2013;73(20):6219–29.

Cohen KJ, Jabado N, Grill J. Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas - Current management and new biologic insights. Is there a glimmer of hope? Vol. 19, Neuro-Oncology. Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 1025–34.

Frazier JL, Lee J, Thomale UW, Noggle JC, Cohen KJ, Jallo GI. Treatment of diffuse intrinsic brainstem gliomas: Failed approaches and future strategies - A review. Vol. 3, Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. 2009. p. 259–69.

Grimm SA, Chamberlain MC. Brainstem glioma: A review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(5):1-8.

Mount CW, Majzner RG, Sundaresh S, Arnold EP, Kadapakkam M, Haile S, et al. Potent antitumor efficacy of anti-GD2 CAR T cells in H3-K27M+ diffuse midline gliomas letter. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):572–9.

Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J, et al. Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nat Genet. 2012/01/31 ed. 2012;44(3):251–3.

Lu VM, Alvi MA, McDonald KL, Daniels DJ. Impact of the H3K27M mutation on survival in pediatric high-grade glioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;23(3):308–16.

Reynolds N, Salmon-Divon M, Dvinge H, Hynes-Allen A, Balasooriya G, Leaford D, et al. NuRD-mediated deacetylation of H3K27 facilitates recruitment of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 to direct gene repression. EMBO J. 2012;31(3):593–605.

Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454(7205):766–70.

Piunti A, Hashizume R, Morgan MA, Bartom ET, Horbinski CM, Marshall SA, et al. Therapeutic targeting of polycomb and BET bromodomain proteins in diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Nat Med. 2017;23(4):493–500.

La Madrid AM, Hashizume R, Kieran MW. Future clinical trials in DIPG: Bringing epigenetics to the clinic. Vol. 5, Frontiers in Oncology. Frontiers Research Foundation; 2015.

Nagaraja S, Vitanza NA, Woo PJ, Taylor KR, Liu F, Zhang L, et al. Transcriptional Dependencies in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(5):635–652.e6.

Mackay A, Burford A, Carvalho D, Baudis M, Resnick A, Jones C, et al. Pediatric High-Grade and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Article Integrated Molecular Meta-Analysis and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer cell. 2017;520–53.

Veringa SJE, Biesmans D, van Vuurden DG, Jansen MHA, Wedekind LE, Horsman I, et al. In vitro drug response and efflux transporters associated with drug resistance in pediatric high grade glioma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):1-10.

Lieberman NAP, Degolier K, Kovar HM, Davis A, Hoglund V, Stevens J, et al. Characterization of the immune microenvironment of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: Implications for development of immunotherapy. Neuro-Oncol. 2019;21(1):83–94.

Lin GL, Nagaraja S, Filbin MG, Suvà ML, Vogel H, Monje M. Non-inflammatory tumor microenvironment of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6(1):51.

Lin GL, Monje M. A protocol for rapid post-mortem cell culture of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). J Vis Exp. 2017;2017(121):1-8.

Buczkowicz P, Zarghooni M, Bartels U, Morrison A, Misuraca KL, Chan T, et al. Aurora kinase B is a potential therapeutic target in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Brain Pathol. 2013;23(3):244–53.

Chornenkyy Y. Poly-ADP-ribose-polymerase as a therapeutic target in paediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and paediatric high grade astrocytoma; 2015.

Halvorson KG, Barton KL, Schroeder K, Misuraca KL, Hoeman C, Chung A, et al. A high-throughput in vitro drug screen in a genetically engineered mouse model of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma identifies BMS-754807 as a promising therapeutic agent. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):1-16.

Caretti V, Hiddingh L, Lagerweij T, Schellen P, Koken PW, Hulleman E, et al. WEE1 kinase inhibition enhances the radiation response of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(2):141–50.

Mueller S, Hashizume R, Yang X, Kolkowitz I, Olow AK, Phillips J, et al. Targeting wee1 for the treatment of pediatric high-grade gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. 2014;16(3):352–60.

Truffaux N, Philippe C, Paulsson J, Andreiuolo F, Guerrini-Rousseau L, Cornilleau G, et al. Preclinical evaluation of dasatinib alone and in combination with cabozantinib for the treatment of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2015;17(7):953–64.

Meel MH, Sewing ACP, Waranecki P, Metselaar DS, Wedekind LE, Koster J, et al. Culture methods of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma cells determine response to targeted therapies. Exp Cell Res. 2017;360(2):397–403.

Blandin D, Litzler T, Guérin R, et al. Hypoxic Environment and paired hierarchical 3D and 2D models of pediatric H3.3-mutated gliomas recreate the patient tumor complexity. Cancers. 2019;11(12):1875.

Jallo GI, Penno M, Sukay L, Liu JY, Tyler B, Lee J, et al. Experimental models of brainstem tumors: Development of a neonatal rat model. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21(5):399–403.

Liu Q, Liu R, Kashyap MV, Agarwal R, Shi X, Wang CC, et al. Brainstem glioma progression in juvenile and adult rats: laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(5):849–55.

Sho A, Kondo S, Kamitani H, Otake M, Watanabe T. Establishment of experimental glioma models at the intrinsic brainstem region of the rats. Neurol Res. 2007;29(1):36–42.

Misuraca KL, Cordero FJ, Becher OJ. Pre-clinical models of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:1-7.

Hashizume R, Ozawa T, Dinca EB, Banerjee A, Prados MD, James CD, et al. A human brainstem glioma xenograft model enabled for bioluminescence imaging. J Neurooncol. 2009;96(2):151–9.

Caretti V, Zondervan I, Meijer DH, Idema S, Vos W, Hamans B, et al. Monitoring of tumor growth and post-irradiation recurrence in a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma mouse model. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(4):441–51.

Aoki Y, Hashizume R, Ozawa T, Banerjee A, Prados M, James CD, et al. An experimental xenograft mouse model of diffuse pontine glioma designed for therapeutic testing. J Neurooncol. 2012;108(1):29–35.

Hashizume R, Smirnov I, Liu S, Phillips JJ, Hyer J, McKnight TR, et al. Characterization of a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma cell line: Implications for future investigations and treatment. J Neurooncol. 2012;110(3):305–13.

Richmond A, Yingjun S. Mouse xenograft models vs GEM models for human cancer therapeutics. Vol. 1, DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms. 2008. p. 78–82.

Huse JT, Holland EC. Genetically engineered mouse models of brain cancer and the promise of preclinical testing. Brain Pathol. 2009;19(1):132–43.

Misuraca KL, Hu G, Barton KL, Chung A, Becher OJ. A Novel Mouse Model of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Initiated in Pax3-Expressing Cells. Neoplasia. 2016;18(1):60–70.

Welby JP, Kaptzan T, Wohl A, Peterson TE, Raghunathan A, Brown DA, et al. Current murine models and new developments in H3K27M diffuse midline gliomas. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1–8.

Barton KL, Misuraca K, Cordero F, Dobrikova E, Min HD, Gromeier M, et al. PD-0332991, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, significantly prolongs survival in a genetically engineered mouse model of brainstem glioma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):1-7.

Yadavilli S, Scafidi J, Becher OJ, Saratsis AM, Hiner RL, Kambhampati M, et al. The emerging role of NG2 in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(14):12141–55.

Cordero FJ, Huang Z, Grenier C, He X, Hu G, McLendon RE, et al. Histone H3.3K27M Represses p16 to Accelerate Gliomagenesis in a Murine Model of DIPG. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15(9):1243–54.

Fortin J, Tian R, Zarrabi I, Hill G, Williams E, Sanchez-Duffhues G, et al. Mutant ACVR1 arrests glial cell differentiation to drive tumorigenesis in pediatric gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(3):308–323.e12.

Long W, Yi Y, Chen S, Cao Q, Zhao W, Liu Q. Potential new therapies for pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Vol. 8, Frontiers in pharmacology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2017.

Paugh BS, Broniscer A, Baker SJ, Qu C, Jones C, Liu Z, et al. Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3061–8.

Gilbertson RJ, Bentley L, Hernan R, Junttila TT, Frank AJ, Haapasalo H, et al. ERBB receptor signaling promotes ependymoma cell proliferation and represents a potential novel therapeutic target for this disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2002/10/11 ed. 2002;8(10):3054–64.

Massimino M. Bode, Biassoni, Fleischhack, Bode U, Biassoni V, et al. Nimotuzumab for pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11(2):247–56.

Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Sobol RW, Nikiforova MN, Lyons-Weiler MA, Laframboise WA, et al. IDH1 mutations are common in malignant gliomas arising in adolescents: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27(1):87–94.

Geoerger B, Hargrave D, Thomas F, Ndiaye A, Frappaz D, Andreiuolo F, et al. Innovative therapies for children with cancer pediatric phase I study of erlotinib in brainstem glioma and relapsing/refractory brain tumors. Neuro-Oncol. 2011;13(1):109–18.

Chornenkyy Y, Agnihotri S, Yu M, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Golbourn B, et al. Poly-ADP-ribose polymerase as a therapeutic target in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric high-grade astrocytoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(11):2560–8.

Warren KE, Killian K, Suuriniemi M, Wang Y, Quezado M, Meltzer PS. Genomic aberrations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;14(3):326–32.

Hummel TR, Salloum R, Drissi R, Kumar S, Sobo M, Goldman S, et al. A pilot study of bevacizumab-based therapy in patients with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2016;127(1):53–61.

Hashizume R, Andor N, Ihara Y, Lerner R, Gan H, Chen X, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of histone demethylation as a therapy for pediatric brainstem glioma. Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1394–6.

Bagcchi S. Panobinostat active against diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Vol. 16, The Lancet. Oncology. 2015. p. e267.

Helin K, Dhanak D. Chromatin proteins and modifications as drug targets; 2013.

Wiese M, Schill F, Sturm D, Pfister S, Hulleman E, Johnsen SA, et al. No significant cytotoxic effect of the EZH2 Inhibitor tazemetostat (EPZ-6438) on pediatric glioma cells with wildtype histone 3 or mutated histone 3.3. Klin Padiatr. 2016;228(3):113–7.

Mohammad F, Weissmann S, Leblanc B, Pandey DP, Højfeldt JW, Comet I, et al. EZH2 is a potential therapeutic target for H3K27M-mutant pediatric gliomas. Nat Med. 2017;23(4):483–92.

Agger K, Cloos PAC, Christensen J, Pasini D, Rose S, Rappsilber J, et al. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449(7163):731–4.

Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, et al. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1067–73.

Chung C, Sweha SR, Pratt D, Tamrazi B, Panwalkar P, Banda A, et al. Integrated metabolic and epigenomic reprograming by H3K27M mutations in diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2020;38(3):334–349.e9.

Michealraj KA, Kumar SA, Kim LJY, Cavalli FMG, Przelicki D, Wojcik JB, et al. Metabolic regulation of the epigenome drives lethal infantile ependymoma. Cell. 2020;181(6):1329–1345.e24.

Chen LH, Pan C, Diplas BH, Xu C, Hansen LJ, Wu Y, et al. The integrated genomic and epigenomic landscape of brainstem glioma. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3077.

Suter RK, Rodriguez-Blanco J, Ayad NG. Epigenetic pathways and plasticity in brain tumors. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;145:105060.

Brown CE, Alizadeh D, Starr R, Weng L, Wagner JR, Naranjo A, et al. Regression of glioblastoma after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2561–9.

Mirzaei HR, Rodriguez A, Shepphird J, Brown CE, Badie B. Chimeric antigen receptors T cell therapy in solid tumor: challenges and clinical applications. Front Immunol. 2017; [cited 2020 Oct 14];8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5744011/.

Donovan LK, Delaidelli A, Joseph SK, Bielamowicz K, Fousek K, Holgado BL, et al. Locoregional delivery of CAR T cells to the cerebrospinal fluid for treatment of metastatic medulloblastoma and ependymoma. Nat Med. 2020;.

Nellan A, Rota C, Majzner R, CM L-MC, Griesinger AM, Mulcahy Levy JM, et al. Durable regression of medulloblastoma after regional and intravenous delivery of anti-HER2 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):30.

Theruvath J, Sotillo E, Mount CW, Graef CM, Delaidelli A, Heitzeneder S, et al. Locoregionally administered B7-H3-targeted CAR T cells for treatment of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):712–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge BioRender for our illustrations.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research ( PJT-155967 and PJT-153104), Meagan's Hug (Meagan Bebenek Foundation), b.r.a.i.nchild and the Wiley Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design of manuscript: D.S., M.S.T., J.T.R.; literature review and writing of manuscript: D.S.; critical editing of manuscript: D.S., M.S.T., R.V.O., J.I., J.T.R.; manuscript artwork and illustrations: S.L.K. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Not applicable

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Srikanthan, D., Taccone, M.S., Van Ommeren, R. et al. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: current insights and future directions. Chin Neurosurg Jl 7, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-020-00218-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-020-00218-w