Abstract

Background

The prevalence of mental health concerns and risky health behaviours among young people is of global concern. A large proportion of young people in New Zealand (NZ) are affected by depression, suicidal ideation and other mental health concerns, but the majority do not access help. For NZ indigenous Māori, the burden of morbidity and mortality associated with mental health is considerably higher. Targeted screening for risky behaviours and mental health concerns among youth in primary care settings can lead to early detection and intervention for emerging or current mental health and psychosocial issues. Opportunistic screening for youth in primary care settings is not routinely undertaken due to competing time demands, lack of context-specific screening tools and insufficient knowledge about suitable interventions. Strategies are required to improve screening that are acceptable and appropriate for the primary care environment. This article outlines the development, utilisation and ongoing evaluation and implementation strategies for YouthCHAT.

YouthCHAT

YouthCHAT is a rapid, electronic, self-report screening tool that assesses risky health-related behaviours and mental health concerns, with a ‘help question’ that enables youth to prioritise areas they want help with. The young person can complete YouthCHAT in the waiting room prior to consultation, and after completion, the clinician can immediately access a summary report which includes algorithms for stepped-care interventions using a strength-based approach. A project to scale up the implementation is about to commence, using a co-design participatory research approach to assess acceptability and feasibility with successive roll-out to clinics. In addition, a counter-balanced randomised trial of YouthCHAT versus clinician-administered assessment is underway at a NZ high school.

Conclusion

Opportunistic screening for mental health concerns and other risky health behaviours during adolescence can yield significant health gains and prevent unnecessary morbidity and mortality. The systematic approaches to screening and provision of algorithms for stepped-care intervention will assist in delivering time efficient, early, more comprehensive interventions for youth with mental health concerns and other health compromising behaviours. The early detection of concerns and facilitation to evidence-based interventions has the potential to lead to improved health outcomes, particularly for under-served indigenous populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental health problems and risky behaviours are common in New Zealand’s young people

Mental health concerns and health risk behaviours, such as tobacco, alcohol and other drug use, physical inactivity and sexual risk behaviours, are initiated and often consolidated during adolescence. Depressive and anxiety disorders and self-harm (including suicide) are three of the top five causes of loss of disability-adjusted life years in 15–19 years old [1]. A quarter of New Zealand’s (NZ’s) young people are affected by depression and anxiety, and over half engage in hazardous drinking by the age of 18 [2, 3]. Young people with long-term physical conditions are also at increased risk of mental health problems, particularly anxiety and depression [4,5,6]. Suicide is the leading cause of death for NZ youth aged 15–24 years and second leading cause for those aged 10–14 years [7]. For Māori, NZ’s indigenous population, the burden of morbidity and mortality associated with mental health is considerably higher, with Māori males living in deprived areas having the highest rates of suicide [8, 9] and disproportionately high rates of depressive symptoms [8, 10].

Early detection and treatment of these problems is important for both individuals and society

Family and friends play a critical part in helping young people through difficult periods in their lives; however, the development of mental health issues are frequently only recognised when a crisis occurs [11, 12]. Early identification of emerging mental health or psychosocial issues gives health professionals the opportunity to work with the young person to recognise and nurture their own positive qualities, assets and pro-social relationships. Evidence shows that developing problem-solving skills and fostering help-seeking behaviours can make young people more resilient during difficult times [13].

The World Health Organization recognises the need for appropriately targeted services to address the unique health and social needs of youth [1, 14]. Policy documents from numerous NZ organisations have underscored the importance of delivering more integrated youth services, with collaboration between social, health, education and other sectors to address the challenges, and intervening earlier when problems emerge, and advocate for reduction in inequity among Māori and other vulnerable youth [11, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Despite the availability of effective treatments, 75% of NZ’s adolescent population do not access help from primary care to address these concerns [2, 22]. Early detection and intervention is paramount for youth who have developed, or who are at risk of developing, mental health conditions; however, this cannot occur unless those who are experiencing these issues are identified and offered help [23,24,25,26]. Assessment and early intervention for youth mental health and psychosocial issues in primary care must use user-friendly screening tools that can be adapted to be usable and sustainable in different clinical contexts [27, 28].

The most common access to primary health care for NZ youth is through general practice [23, 29]. For Māori and others living in areas of high deprivation, health care delivered through school-based and youth-specific health clinics can improve access significantly [30,31,32,33]. Youth with mental health issues are often seen in primary health care in terms of problem or risk needing management [34, 35]; however, they do have strengths and abilities enabling them to be involved in the development of their plan of care [34, 35], which suggests that preventative screening and the provision of self-management tools may be a beneficial approach. Young people can be helped to develop healthy coping strategies through nurturing their resilience, developed from positive characteristics in their lives such as family and peer support, connectedness to their community and culture, and involvement in groups where they feel accepted and valued [36,37,38]. A strength-based approach helps young people to develop support systems and coping strategies to facilitate better lifestyle choices and promote positive adaptation when faced with future challenges [36, 39, 40].

Depressive disorders place a high financial strain on NZ’s economy and are the major contributing factor in youth suicide and youth mental health issues. Risk-taking behaviours developed during adolescence contribute to long-term poor health and socio-economic problems [25, 34, 41]. Untreated mental health and behavioural issues can have personal costs on youth, their families and local communities; there are also enormous societal costs associated with the flow on effects of untreated disorders [42, 43]. A NZ longitudinal study that followed children with mental illness and their siblings without mental illness for a period of 40 years found that as adults, those with mental illness had more time off work for sick leave, earned 20% less, and had fewer assets [44]. They were also 11% less likely to be married. The research suggests that there is a lifetime cost of NZ$300,000 of family income and a total lifetime economic cost for all affected of 2.1 trillion dollars (based on the assumption that one in 20 adults experiences mental health problems in childhood). NZ research has found that psychiatric disorder among young adults is associated with lower income and living standards and reduced workforce participation [45].

Screening may aid early detection of mental health problems and risky behaviour in young people

Health professionals in general practice, school and youth clinics are well placed to undertake opportunistic screening of young people for mental health and psychosocial issues and to provide early intervention. Despite the burden of mental health morbidity in the community, there is evidence that health professionals in general practice do not opportunistically discuss emotional or behavioural issues with youth [46, 47], unless the issues are serious or actively raised by the young person [48]. Health professionals in general practice give reasons for this lack of engagement as being shortage of time, experience and skills in youth mental health, and inadequate knowledge of suitable interventions once such concerns have been identified [2, 49].

Young people attending primary care commonly have more than one psychosocial or mental health issue that needs attention [27, 34, 50, 51]. Identifying such issues relies on a thorough psychosocial assessment by the clinician, during which the young person must disclose personal information to someone whom they may only have recently met [24]. While there are several screening tools available [27], they can be time-consuming and may not all be suitable for different settings [33, 52].

The HEEADSSS assessment (Home, Education, Eating, Activities, Drugs and Alcohol, Sexuality, Suicide/Depression, Safety) is a clinician-administered interview-based assessment of youth that can help identify mental health and substance use problems [53]. Currently, all NZ year 9 (13–14 years old) students in low decile (areas of high social deprivation) schools are expected to be assessed for well-being via HEEADSSS. While HEEADSSS offers a straightforward, holistic and gradual approach to assessing young people across many domains [53], it is a face-to-face assessment, not a screening tool. Its drawbacks include its lack of validation, cost of resourcing, lack of integration with young person’s primary care provider and time required for administration, which can be in excess of 40 min and may take up to 2 h [52].

Screening and case-finding are terms sometimes used synonymously [54], both involving the early detection of a condition. However, screening and case-finding may differ with respect to their setting and the expectations of their populations [55]. Screening generally refers to testing an asymptomatic population for the presence of a condition which if identified can lead to early intervention reducing subsequent morbidity or mortality. Case-finding involves seeking early detection of a condition when a patient attends for an unrelated concurrent disorder, and may or may not be symptomatic. For a specific condition, testing will depend on a number of criteria including the age and gender of the patient and the presence of any risk factors which might increase their likelihood of being a positive case (increase the pre-test probability).

For screening to be justified, the WHO and the Journal of the American Medical Association evidence-based medicine working group require that it is an important health problem, with a suitable acceptable test and a clear diagnosis, that the benefits outweigh any harms and that early intervention is effective and cost-effective [56, 57]. The US Preventive Services Task Force similarly directs that there must be an accurate test for the condition and scientific evidence that screening can prevent adverse outcomes.

In general, there is good evidence for targeted screening in primary care settings for risk behaviours such as tobacco use [58], alcohol [59] and illicit drug use [60], problem gambling [61] and physical inactivity [62], and mental health issues including depression [63] and anxiety [64], given appropriate intervention is then available. Young people are more vulnerable to developing risk behaviours and mental health issues which can be carried on into adulthood. For health outcomes to be improved, early detection of emerging or current issues and appropriate intervention is paramount [2, 24,25,26], and thus targeted screening for risk behaviours and mental health issues among youth attending primary care is justified.

While studies using accepted screening criteria may have been conducted on the effectiveness of screening, there still may not be consensus on whether or not to screen. Even meta-analyses with the same research question, such as the evidence for screening for depression, can result in opposing recommendations [65]. Screening criteria act as guidelines, but different components may be given different weightings. Ultimately, the decision to systematically screen or case-find or not will be directed by value judgements and the importance placed on various aspects, including consideration of the specific population in question and availability of potential interventions. Thus, the implementation of a national mental health screening tool at a local level may not succeed if community and cultural priorities regarding health and well-being are not understood [66]. For implementation of interventions to be successful, there must be consultation and input from the local community, so that their health needs can be met [66,67,68].

Electronic screening may have a role to play in detecting mental health problems and risky behaviour in young people

Electronic screening (e-screening) has been shown to provide consistent results, lead to more disclosure and reduce staff time [69, 70]. There is emerging research that suggests youth prefer to complete self-assessment via electronic means [24, 71,72,73]. E-screening is associated with youth disclosing sensitive information without fear of being judged, structuring their thoughts and prioritising the issues for which they wanted help. Young people feel more in control and have more input into their ongoing care [24], making it more likely that they will see any intervention as beneficial [35].

YouthCHAT is a potentially useful screening instrument for identifying mental health problems and risky behaviour in young people

YouthCHAT is a youth-specific, self-administered, holistic risk behaviour and mental health e-screening and intervention planning programme that has been developed in NZ. The aim of this article is to discuss its rationale, development, progressive implementation and potential impact on youth health and well-being.

YouthCHAT

Description of YouthCHAT

YouthCHAT is a composite screener for psychosocial issues that was developed from an adult-oriented screening tool, the electronic Case-Finding and Help Assessment Tool (eCHAT) in NZ. eCHAT is a self-report rapid (5–15 min) tool screening for substance misuse, problem gambling, depression, anxiety, exposure to abuse, difficulty controlling anger and physical inactivity in primary care settings [74, 75]. A key feature is the help question, which enables patients to indicate areas where they would like help, gauge their readiness to change, and prioritise issues where they have problems in more than one domain [76,77,78]. Initially developed, evaluated and validated as a paper tool [79,80,81,82,83], the electronic version enables branching logic. Positive responses for smoking, alcohol and other drug use lead directly to the WHO Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) [84], for depression to the Patient Health Questionnaire - 9 (PHQ-9) [85] and for anxiety to the GAD-7 [86]. With the electronic format, the results are able to be communicated immediately to a relevant care provider and include a summary of the assessments and help question responses as a preface to the detailed responses. There is also the potential for development of electronic decision support and stepped-care algorithms.

Young people self-administer YouthCHAT electronically prior to their consultation. Once completed, the health provider/clinician is immediately able to access a summary report indicating which modules screened positive, the severity (e.g. from depression PHQ-A score) and whether help is sought. Review of this summary facilitates a conversation between the young person and health provider (for example family physician or nurse) and the shared decision-making of an action plan. YouthCHAT provides a guide to effective evidence-based interventions using a stepped-care management model ranging from self-help (for example helpline numbers, handouts and web addresses for psychoeducation and e-therapies), to GP or primary care nurse brief interventions or provision of relevant medication (such as nicotine replacement), to referral to community agencies, and services, and finally referral to secondary care (mental health and drug and alcohol services). This approach engages youth and empowers them to have input into their management plans, encourages them to develop strengths and interests and increases the chances of effective intervention.

Development of YouthCHAT

The first version of YouthCHAT was developed in 2015. Additional modules relating to sexual health (concerns about sexual orientation/identity, risky sexual behaviours and unwanted sexual activity) were added to the existing nine modules (smoking, drinking and other drug use, gambling, depression, anxiety, exposure to abuse, anger control and physical inactivity). The ASSIST for drinking and recreational drug use was replaced by the youth-friendly Substances and Choices Scale (SACS), developed and validated in NZ [87] and the PHQ-9 with PHQ-A (modified for adolescents). It was also made available in both English and Māori languages. It was successfully implemented in rural clinic for rural youth, especially Māori, and favourably received by both young patients and clinic staff [88].

In 2016, YouthCHAT was updated with stakeholder assistance from a low decile high school to match the modules of the face-to-face HEEADSSS assessment. This involved adding three modules on eating and conduct disorders and areas of stress in their lives.

Development of both eCHAT and YouthCHAT has involved stakeholder engagement including patients, clinical staff, community agencies and Māori in a number of different forums [79, 81, 83, 89, 90].

Current clinical utilisation and research of YouthCHAT

Implementation of YouthCHAT is soon to be underway for use in NZ settings with large Māori populations in nurse-led youth clinics, school-based clinics, and general practice. It is anticipated that a successful roll-out will be associated with improved health and social outcomes through early identification and intervention of mental health concerns, improvement in youth resilience and help-seeking behaviour and an acceptable and time-saving and cost-effective strategy for clinicians to screen for mental health concerns and ultimately improve equity for young Māori [23, 26, 91]. A framework has been developed for scaling up the implementation of YouthCHAT e-screening into primary care environments across other primary healthcare settings.

The feasibility and acceptability of the programme is being researched using an implementation and co-design participatory research approach with a mixed method design [92]. While randomised controlled trials provide evidence about the use of a specific intervention in a controlled setting with a very specific group of patients, this evidence may not be fully transferrable to complex interventions for use in actual clinical contexts [93, 94].

An implementation approach allows the research team to work with the young people and clinic staff to identify aspects that limit or encourage the use of YouthCHAT in each specific clinical context [95]. Strategies to overcome obstacles to its implementation across different settings can be developed and evaluated in order to develop a successful formula to scale up the use of YouthCHAT across a range of primary care contexts. And data from interviews and focus groups, rates of detection for each domain of YouthCHAT, health-seeking behaviour and provision of brief interventions or referrals to secondary care mental health services can be assessed before and after YouthCHAT implementation.

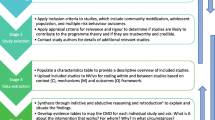

A co-design participatory research approach [96] helps ensure that end-user feedback supports the development of a sustainable implementation of YouthCHAT. This process involves consultation and partnership between researchers, clinicians, young people, support staff, managers and policymakers in research planning and adaptation of the programme in response to feedback. The tailoring of YouthCHAT to each specific setting involves consultation with clinical staff and key community members and cultural leaders. Modifiable elements include specific screening modules, determining the screening processes and criteria for that clinic, and identifying local resources, agencies, cultural and community supports that might be included in the stepped-care intention package. Input from the community enables modification of the programme in response to relevant socioeconomic and contextual factors of the targeted region (see Fig. 1). Furthermore, their engagement with, and shared ownership of, the programme optimises the chance of successful implementation.

YouthCHAT has the potential to overcome barriers associated with opportunistic mental health screening of youth, including HEEADSSS assessment, while providing a similar holistic assessment of mental health and lifestyle issues. A counter-balanced randomised trial of YouthCHAT versus HEEADSSS is currently underway at a NZ high school [97].

YouthCHAT is also the screening tool being used in a NZ National Science Challenge project ‘Health Advances through Behavioural Intervention Technologies’ (HABITS) which is developing Internet and app-based psychological interventions to be used by young people, either independently or in association with their youth health worker [98]. The project hopes to increase detection of problems among young people and promote new ways for them to access evidence-based interventions for common mental health concerns. By increasing access to therapy available ‘anywhere and anytime’, HABITS aims to improve mental health in the short-term and demonstrate improved long-term outcomes with better school retention and employment and reduced substance abuse, antisocial behaviour and mental health problems.

Potential impact of YouthCHAT

Early detection of mental health issues and risky health behaviours in young people may lead to many downstream social as well as financial benefits, including improved physical health, reduction in school dropout, increased employment, less suicides, more successful relationships including marriage, and a reduction in crime rates.

The average cost of keeping a New Zealander in prison for 12 months in 2011 was $91,000 or $250 per day [99]. Many incarcerated individuals have substance abuse issues and face problems such as anger management, gambling, mental health problems and more. The longer these problems are left untreated, the more entrenched and harder to treat they become. By focusing on identification and early intervention of high-risk youth, it is possible that YouthCHAT can mitigate these mental health and behaviour issues that are so often the basis for offending and incarceration. The cost ramifications of this can be significant. For example, by helping just one youth avoid a 5-year prison sentence by overcoming mental health and behaviour issues that lead to incarceration, YouthCHAT could save NZ $455,000.

A national generic framework for mental health services can provide a base from which context-specific processes and policies can be developed [68]. Sharing components of youth mental health in primary care common to all areas can save time and money at the local level. Considerations such as costs and benefits, workforce development and reaching vulnerable groups may help inform creation of services. A national framework can also help develop consistent standards of care based on best practice and measuring of outcomes.

However, the implementation of national mental health strategies at the local level may not succeed if community and cultural priorities regarding health and well-being are not understood [66]. For implementation of interventions to succeed, there must be consultation and input from the local community, so that their health needs can be met [66,67,68].

With sufficient coverage, YouthCHAT data could also be used for monitoring the prevalence of mental health concerns among youth within a population—this would help to prioritise services and workforce development in areas of high need. Collated YouthCHAT data can provide information on identification of mental health and addiction issues in youth, and inform provision of appropriate stepped-care interventions, from self-management to practice-delivered brief interventions and medications, community-level services and secondary care services. Collated anonymised data can be provided at various levels from individual practices to practice networks and regional health services. This can assist in appropriate provision of mental health and addiction services to align service provision with population need, and improve services through benchmarking. A data analytics portal has been designed and prototyped to support a range of users including practice managers, clinical directors and health policy analysts based on initial YouthCHAT field trial data [100].

Conclusions

Opportunistic screening for mental health concerns and other risky health behaviours during adolescence can yield significant health gains and prevent unnecessary morbidity and mortality, including self-harm and suicide. The systematic approaches to screening and provision of algorithms for stepped-care intervention will assist in delivering time efficient, early, more comprehensive interventions for youth with mental health concerns and other health compromising behaviours. The early detection of concerns and facilitation to evidence-based interventions has the potential to lead to improved health outcomes, particularly for under-served indigenous populations.

Abbreviations

- ASSIST:

-

Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test

- eCHAT:

-

Electronic Case-finding and Help Assessment Tool

- GAD-7:

-

General Anxiety Disorder - 7

- HABITS:

-

Health Advances through Behavioural Intervention Technologies

- HEEADSSS:

-

Home, Education, Eating, Activities, Drugs and Alcohol, Sexuality, Suicide/Depression, Safety

- NZ:

-

New Zealand

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire - 9

- PHQ-A:

-

PHQ-9 modified for Adolescents

- SACS:

-

Substances and Choices Scale

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. Geneva: WHO; 2017. p. 176.

Ministry of Health. Evaluation report: the youth primary mental health service. Wellington: MoH; 2016.

Fleming TM, Clark T, Denny S, Bullen P, Crengle S, Peiris-John R, Robinson E, Rossen FV, Sheridan J, Lucassen M. Stability and change in the mental health of New Zealand secondary school students 2007-2012: results from the national adolescent health surveys. Aust NZ J Pyschiat. 2014;48(5):472–80.

Denny S, de Silva M, Fleming T, Clark T, Merry S, Ameratunga S, Milfont T, Farrant B, Fortune SA. The prevalence of chronic health conditions impacting on daily functioning and the association with emotional well-being among a national sample of high school students. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(4):410–5.

Marin TJ, Chen E, Munch JA, Miller GE. Double-exposure to acute stress and chronic family stress is associated with immune changes in children with asthma. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(4):378–84.

Pao M, Bosk A. Anxiety in medically ill children/adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(1):40–9.

New Zealand Mortality Review Data Group. Child and youth mortality review committee 12th data report 2011–15. Dunedin: University of Otago; 2016. p. 83.

Crengle S, Clark T, Robinson E, Bullen P, Dyson B, Denny S, Fleming T, Fortune S, Peiris-John R, Utter J, et al. The health and wellbeing of Māori New Zealand secondary school students in 2012. Te Ara Whakapiki Taitamariki: Youth’12. Auckland: The University of Auckland; 2013. p. 80.

Statistics New Zealand. New Zealand social indicators: suicide. Wellington: Stats NZ; 2013.

Crengle S, Clark TC, Robinson E, Bullen P, Dyson B, Denny S, Fleming T, Fortune S, Peiris-John R, Utter J, et al. The health and wellbeing of Māori New Zealand secondary school students in 2012. Te Ara Whakapiki Taitamariki: Youth’12. Auckland: The University of Auckland; 2013.

Ministry of Health. Prime minister’s youth mental health project. Wellington: MOH; 2012.

Clark T, Robinson E, Crengle S, Fleming T, Ameratunga S, Denny S, Bearinger L, Sieving R, Saewyc E. Risk and protective factors for suicide attempt among indigenous Maori youth in New Zealand: the role of family connection as a moderating variable. J Aborig Health. 2011;7(1):16–31.

Dray J, Bowman J, Freund M, Campbell E, Wolfenden L, Hodder RK, Wiggers J. Improving adolescent mental health and resilience through a resilience-based intervention in schools: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):289.

World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013. p. 48.

Auckland District Health Board. The integrated child and youth mental health and addiction direction 2013-2023. Auckland: ADHB; 2013. p. 22.

Mental Health Commission. Blueprint II: improving mental health and well-being for all New Zealanders. How things need to be. Wellington: Mental Health Commission; 2012. p. 48.

Mental Health Commission. Blueprint II: improving mental health and well-being for all New Zealanders. Making change happen. Wellington: Mental Health Commission; 2012. p. 102.

Ministry of Health. Rising to the challenge: the mental health and addiction service plan development plan 2012-2017. Draft for consultation, vol. 2012. Wellington: Ministry of Health. p. 61.

Ministry of Health. New Zealanders live longer, healthier, more independent lives: statement of intent 2014 to 2018. Wellington: MoH; 2014. p. 2.

Ministry of Health. New Zealand suicide prevention action plan 2013–2016. Wellington: MoH; 2013. p. 8.

Ministry of Health, Te Puni Kōkiri, Ministry of Social Development. Whānau Ora programme. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2010.

Mariu KR, Merry SN, Robinson EM, Watson PD. Seeking professional help for mental health problems, among New Zealand secondary school students. Clin. 2012;17(2):284–97.

Ministry of Health. Evaluation report: the youth primary mental health service. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2016.

Bradford S, Rickwood D. Young people’s views on electronic mental health assessment: prefer to type than talk? J Child Fam Stud. 2015:1213–21.

Improving the transition reducing social and psychological morbidity during adolescence. Wellington: Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee; 2011.

Mental health and addiction workforce action plan 2017-2021. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2017.

Bradford S, Rickwood D. Psychosocial assessments for young people: a systematic review examining acceptability, disclosure and engagement, and predictive utility. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2012:111–25.

Sanci L, Grbazch B, Chondros P, Sheill A, Pirkis J, Sawyer S, Hegarty K, Patterson E, Cahill H, Ozer E, et al. The prevention access and risk taking in young people (PARTY) project protocol: a cluster randomised controlled trial of health risk screening and motivational interviewing for young people presenting to general practice. BMC Public Health. 2012;

Denny S, Farrant B, Cosgriff J, Hart M, Cameron T, Johnson R, Robinson E. Access to private and confidential health care among secondary school students in New Zealand. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):285–91.

Ministry of Health. Evaluation of youth one stop shops. Wellington: MoH; 2009. p. 206.

Bidwell S. Improving access to primary health care for children and youth: a review of the literature for the Canterbury Clinical network Child and Youth Workstream. IT, Community Christchurch: Canterbury District Health Board; 2013.

Denny S, Grant S, Galbreath R, Clark T, Fleming T, Bullen P, Dyson B, Crengle S, Fortune S, Peiris-John R, et al. Health services in New Zealand secondary schools and the associated health outcomes for students. Auckland: University of Auckland; 2014.

Buckley S, McDonald J, Mason D, Gerring Z, Churchward M, Cumming J. Nursing services in New Zealand secondary schools: a summary. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2009.

Taliaferro L, Borowsky I. Beyond prevention: promoting healthy youth development in primary care. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102:S317–21.

Sanders J, Munford R, Thimasarn-Anwar T, Liebenberg L, Ungar M. The role of positive youth development practices in building resilience and enhancing wellbeing for at-risk youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;42:40–53.

Bagshaw S, Fleming T, Zonneveld R. Managing frequently encountered mental health problems in young people: non-pharmacological strategies. Best Pract J. 2015;72.

Fleming T, Merry S, Robinson E, Denny S, Watson P. Self-reported suicide attempts and associated risk and protective factors among secondary school students in New Zealand. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2007;41:213–21.

Logan J, Crosby A, Hamburger M. Suicidal ideation, friendships with delinquents, social and differential associations by sex findings among high-risk pre/early adolescent population. Crisis. 2011;32(6):299–309.

Ungar M, Theron L, Liebenberg L, Tian G, Restrepo A, Sanders J, Munford R, Russell S. Patterns of individual coping, engagement with social supports and use of formal services among a five-country sample of resilient youth. Global Ment Health. 2015;2(e21). https://doi-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/10.1017/gmh.2015.19.

Taliaferro L, Borowsky I. Beyond prevention: promoting healthy youth development in primary care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:S317–21.

Collaborative for Research and Training in Youth Health and Development. Youth health: enhancing the skills of primary health care practitioners in caring for all young New Zealanders, a resource manual. Christchurch: Collaborative for Research andTraining in Youth Health and Development Trust; 2011.

The Australian Health Policy Collaboration: The costs and impacts of a deadly combination: serious mental illness with concurrent chronic disease. Melbourne: Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; 2016.

Access Economics Pty Limited: The economic impact of youth mental illness.; 2009.

Smith JP, Smith GC. Long-term economic costs of psychological problems during childhood. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):110–5.

Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Burden of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood and life outcomes at age 30. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):122–7.

Haller D, Sanci L, Patton G, Sawyer S: Toward youth friendly services: a survey of young people in primary care. The General Practice and Primary Care Research Conference: 2006; Perth, Australia; 2006.

Key J. Cabinet paper: measures to improve youth mental health. Wellington: Office of the Prime Minister; 2012. p. 10.

Roberts J, Sanci L, Haller D. Global adolescent health; is there a role for general practice? Br J Gen Pract. 2012:608–10.

Sanci L, Grabsch B, Chondros P, Shiell A, Pirkis J, Sawyer S, Hegarty K, Patterson E, Cahill H, Ozer E, et al. The prevention access and risk taking in young people (PARTY) project protocol: a cluster randomised controlled trial of health risk screening and motivational interviewing for young people presenting to general practice. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:400.

Schaeuble K, Haglund K, Vukovich M. Adolescents’ preferences for primary care provider interactions. J Spec Paed Nurs. 2010;15(3):202–10.

Viner R, Barker M. Young people’s health: the need for action. BMJ. 2005;330(7496):901–3.

Ministry of Health. Evaluation of healthy community schools initiative in AIMHI schools. Wellington: MoH; 2009. p. 149.

Bagshaw S, Fleming T, Zonneveld R. Addressing mental health and wellbeing in young people. Best Pract J. 2015;10

Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178(8):997–1003.

Sackett D, Haynes R, Guyatt G, Tugwell P. Early diagnosis. In: Sackett D, et al., editors. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1991. p. 153–70.

Barratt A, Irwig L, Glasziou P, Cumming RG, Raffle A, Hicks N, Gray JA, Guyatt GH. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XVII. How to use guidelines and recommendations about screening. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(21):2029–34.

Wilson JM, Jungler G. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1968.

US Preventive Services Task Force: Final recommendation statement: tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women. In. Rockville, MS, USA: USPSTF; 2016.

US Preventive Services Task Force: Alcohol misuse: screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care. In. Rockville, MD, USA: USPSTF; 2016.

Lanier D, Ko S: Screening in primary care settings for illicit drug use: assessment of screening instruments: a supplemental evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. In: Evidence Syntheses, No 582. Rockville (MD): US Preventive Services Task Force; 2008.

Problem Gambling Research and Treatment Centre: Guideline for screening, assessment and treatment in problem gambling. In. Clayton, Australia: Monash University; 2011: 126.

Warburton D, Charlesworth S, Ivey A, Nettlefold L, Bredin S. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada’s physical activity guidelines for adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:39.

Siu AL, Force USPST, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, Garcia FA, Gillman M, Herzstein J, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JMA. 2016;315(4):380–7.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Common mental health problems: identification and pathways to care. In: Clinical guideline. London: NICE; 2011. p. 55.

Goodyear-Smith FA, van Driel ML, Arroll B, Del Mar C. Analysis of decisions made in meta-analyses of depression screening and the risk of confirmation bias: a case study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:76.

Smylie J, Anderson M. Understanding the health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: key methodological and conceptual challenges. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;

Mittelmark M. Promoting social responsibility for health: health impact assessment and healthy public policy at the community level. Health Prom Int. 2001;16(3):269–74.

Mulvale G, Kutcher K, Randall G, Wakefield P, Longo C, Abelson J, Winkup J, Fast M. Do national frameworks help in local policy development? Lessons from Yukon about the evergreen child and youth mental health framework. Can J Comm Mental Health. 2015;34(4):111–28. doi:10.7870/cjcmh-2015-011.

Renker PR. Breaking the barriers: the promise of computer-assisted screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwif Wom Health. 2008;53(6):496–503.

Harris S, Knight J, Van Hook S, Sherritt L, Brooks T, Kulig JW, Nordt C, Saitz R. Adolescent substance use screening in primary care: validity of computer self-administered vs. clinician-administered screening. Subst Abuse. 2016;37(1):197–203.

Watson PD, Denny SJ, Adair V, Ameratunga SN, Clark TC, Crengle SM, Dixon RS, Fa'asisila M, Merry SN, Robinson EM, et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of a health survey using multimedia computer-assisted self-administered interview. Aust NZ J Pub Health. 2001;25(6):520–4.

Chisolm D, Gardner W, Julian T, Kelleher K. Adolescent satisfaction with computer-assisted behavioural risk screening in primary care. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2008;13(4):163–8.

Harris S, Knight J. Putting the screen in screening: technology-based alcohol screening and brief interventions in medical settings. Alcl Res Curr Rev. 2014;36(1):63–79.

Goodyear-Smith F, Warren J, Bojic M, Chong A. eCHAT for lifestyle and mental health screening in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):460–6.

Goodyear-Smith F, Warren J, Elley C. The eCHAT program to facilitate healthy changes in primary care populations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:177–82.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Coupe N. Asking for help is helpful: validation of a brief lifestyle and mood assessment tool in primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):239–44.

Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Kerse N, Fishman T, Gunn J. Effect of the addition of a “help” question to two screening questions on specificity for diagnosis of depression in general practice: diagnostic validity study. BMJ. 2005;331(7521):884.

Puddifoot S, Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Kerse N, Fishman T, Gunn J. A new case-finding tool for anxiety: a pragmatic diagnostic validity study in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37(4):71–81.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Coupe N, Buetow S. Ethnic differences in mental health and lifestyle issues: results from multi-item general practice screening. NZ Med J. 2005;118(1212):U1374.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Kerse N, Sullivan S, Coupe N, Tse S, Shepherd R, Rossen F, Perese L. Primary care patients reporting concerns about their gambling frequently have other co-occurring lifestyle and mental health issues. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:25.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Tse S. Asian language school student and primary care patient responses to a screening tool detecting concerns about risky lifestyle behaviours. NZ Fam Physic. 2004;31(2):84–9.

Goodyear-Smith F, Coupe N, Arroll B, Elley C, Sullivan S, McGill A. Case-finding of lifestyle and mental health problems in primary care: validation of the ‘CHAT’. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(546):26–31.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Sullivan S, Elley R, Docherty B, Janes R. Lifestyle screening: development of an acceptable multi-item general practice tool. NZ Med J. 2004;117(1205):U1146.

Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Farrell M, Formigoni ML, Jittiwutikarn J, de Lacerda RB, Ling W, Marsden J, Monteiro M, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction. 2008;103(6):1039–47.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Int Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Christie G, Marsh R, Sheridan J, Wheeler A, Suaalii-Sauni T, Black S, Butler R. The substances and choices scale (SACS)—the development and testing of a new alcohol and other drug screening and outcome measurement instrument for young people. Addiction. 2007;102(9):1390–8.

Goodyear-Smith F, Corter A, Suh H. Electronic screening for lifestyle issues and mental health in youth: a community-based participatory research approach. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):140.

Zhu S, Tse S, Goodyear-Smith F, Yuen W, Wong P. Health-related behaviors and mental health in Hong Kong employees. Occ Med. 2016;67(1):26–32.

Elley CR, Dawes D, Dawes M, Price M, Draper H, Goodyear-Smith F. Screening for lifestyle and mental health risk factors in the waiting room: feasibility study of the Case-finding Health Assessment Tool. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(11):e527–34.

Mental Health Commission. Child and youth mental health and addiction. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. 2011;34.

Goodyear-Smith F. Collective enquiry and reflective action in research: towards a clarification of the terminology. Fam Pract. 2016;14:14.

Patsopoulos N. A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(2):217–24.

Peters H, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong A, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2013;347:f6753. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6753.

Peters D, Tran N, Adam T. Implementation research in health: a practical guide. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; 2013.

Goodyear-Smith F, Jackson C, Greenhalgh T. Co-design and implementation research: challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:78.

Thebrew H, Corter A, Goodyear-Smith F, Goldfinch M. Randomised trial comparing the electronic composite psychosocial screener YouthCHAT with a HEEADSSS assessment for young people: a study protocoL. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(7):e135. doi:10.2196/resprot.7995.

National Science Challenge. A better start—E Tipu e Rea: revised research and business plans. Wellington: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment; 2015. p. 112.

Department of Corrections: Prison facts and statistics. In. Wellington; 2011.

Zhang X, Warren J, Corter A, Goodyear-Smith F. A population-level data analytics portal for self-administered lifestyle and mental health screening. Stud Health Tech Inform. 2016;231:152–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

A funding grant from the Starship Foundation Investment in Clinical Research for the study 'Acceptability and utility of electronic screener YouthCHAT for young people with long-term physical conditions attending Starship Hospital and Year 9 Tamaki high school students and its comparison with HEEADSSS assessment' (Thabrew H, Goodyear-Smith F, Corter A) is acknowledged.

Merry S, Warren J, Fleming T, Stasiak K, Christie G, Hopkins S, Shepherd M, Goodyear-Smith F. HABITS. National Science Challenge. 2016–2019.

Goodyear-Smith F. Goodfellow Foundation. eCHAT Project. 2014–2016.

Goodyear-Smith F, Warren J, Arroll B. Faculty Research Development Funds, Staff Research Fund, ‘Feasibility of electronic CHAT’, 2008–2009.

No funding body had input into the design of the studies nor the collection, analysis and interpretation of data nor writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FGS is the lead researcher for YouthCHAT and wrote the initial draft of this manuscript. RM, MD, JW, HT and TC all contributed significantly to the writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

FGS (MBChB, MD, FRNZCGP) is a general practitioner and academic head of the Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care. She has been the lead researcher for eCHAT research over the past 15 years.

RM is a PhD candidate in the Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care. She is a school nurse who completed a research Master of Nursing degree in 2016 with a particular interest in improving outcomes for youth in primary healthcare and will be evaluating the implementation of YouthCHAT for her doctoral studies.

MD (PhD) is the research fellow for YouthCHAT and holds a PhD in psychology. She assists in the iterative tailoring of e-screening/implementation package in response to stakeholder needs.

JW (PhD) is a professor of Health Informatics at the University of Auckland. He has been involved in the development of eCHAT over the past few years and advises on IT aspects of the implementation.

HT (BM, BSc, FRACP, FRANZCP) is a child psychiatrist and paediatrician at Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland, and a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland. He is the lead investigator in the YouthCHAT versus HEEADSSS randomised trial.

TC (PhD) is a registered comprehensive nurse with extensive experience in youth mental, community, sexual, and Māori health and health promotion and senior lecturer at the School of Nursing, University of Auckland. She assists with engagement with Măori.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Goodyear-Smith, F., Martel, R., Darragh, M. et al. Screening for risky behaviour and mental health in young people: the YouthCHAT programme. Public Health Rev 38, 20 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0068-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0068-1