Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this article is to report a rare case in which a patient presented symptomatic silicon oil brain migration, documented by MRI, several years after vitreoretinal surgery.

Methods

This is a case report with a prospective literature review.

Patients

The patient described in the case report.

Results

Case report.

Discussion/conclusions

For several years, silicone oil (SiO) has been widely used as a long-term intravitreal tamponading agent to treat complex retinal detachments. There are rare reports in the literature demonstrating the migration of SiO into the brain. The aim of this article is to report a rare case in which the patient presented severe headaches several years after vitreoretinal surgery, with migrated SiO appearing in MRI as an oval lesion within the horn of the right lateral ventricle. To the best of our knowledge, there are very few reports of symptomatic SiO brain migration in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main text

Introduction

Silicone oil (SiO) was first described as an intraocular tamponade for retinal detachment in 1962 by Cibis and colleagues [1]. Since then, it has been widely used as a long-term intravitreal tamponading agent to treat complex retinal detachments. Many intraocular complications of SiO have been reported, including cataract formation, oil emulsification with secondary glaucoma, and subretinal oil migration [2, 3].

Infiltration of SiO into the retrolaminar optic nerve was first demonstrated pathologically by Ni et al. in 1983 [4]. Posteriorly, rare reports showed SiO migration and its progression through the optic chiasm and brain [5, 6]. The exact mechanism of why it occurs is not yet fully understood. Various factors might play a role in physical silicone oil migration, such as congenital anatomical deformities (optic pit), long-term elevated intraocular pressure, degeneration of the optic nerve, and migration of phagocytosed emulsified oil bubbles by macrophages [7].

Although it is a rare complication, SiO migration is described in the literature as a benign and non-symptomatic incidental radiographic finding [8]. We report a case in which the patient presented severe headaches several years after vitreoretinal surgery with SiO tamponade. To the best of our knowledge, there are very few reports of symptomatic SiO brain migration in the literature.

Case report

A 67 years old white woman related severe headaches, dating from one month ago. She had no other symptoms and no family history of migraines or glaucoma as well. A pars plana vitrectomy in OD with SiO tamponade (5000 cSt) was performed in 2016 due to a tractional-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment caused by proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The patient evolved with intraocular hypertension and glaucoma in the same eye, being later submitted to a trabeculectomy (2018) and to a cyclophotocoagulation in 2019.

The patient had a vision of no-light perception in OD and 20/50 in OS (+ 3.00 −1.75 × 90). On the slit-lamp biomicroscopy examination of OD, the patient was pseudophakic with a significant posterior capsule opacification, while the left eye was unremarkable. The intraocular pressure was 20\16 mmhg by Goldmann’s applanation tonometry. The posterior segment examination showed the presence of SiO and a total excavation of the optic disc with intense optic disk pallor in OD. There was an inferior retinectomy associated with subretinal PVR next to inferior vascular arcades. In the left eye, there was a physiological optic disc cupping and a PDR.

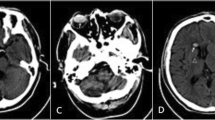

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, demonstrating an ovoid lesion within the frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle. The T2 weighted images showed migrated SiO in the horn of the lateral ventricle, and it can be seen in Figs. 1 and 2a. Figure 2b shows a T1 weighted MRI Sagittal Cut image with a hyperintense ovoid lesion on the frontal horn of the lateral ventricles as well. The patient was evaluated by the neurosurgery department, in which they opted for clinical observation, oral analgesia with metamizole, and close follow-up. According to the patient, the headaches episodes diminished considerably, both in frequency and intensity. We performed panretinal photocoagulation in the left eye due to PDR, and the patient maintained a stable neuro-clinical condition until the submission of this article.

Discussion

The migration of intravitreal silicone oil into the cerebral ventricles remains a rarely described phenomenon, and it may contribute to the misinterpretation of other brain lesions, such as ventricular hemorrhage, colloid cyst, and calcifications [9, 10]. We believe that ocular hypertension and advanced glaucoma developed after the vitreoretinal surgery in our case could have been the probable causes for the silicone oil to migrate [11].

The predominant location of migrated SiO seems to be in the lateral ventricles, which is described to be most likely asymptomatic, compared with the third or fourth ventricles. Intraventricular SiO droplets are described to potentially block the cerebrospinal fluid outflow and temporarily raise intracranial pressure. We hypothesize that this could explain the severe headaches episodes presented by our patient [12].

There are no clear indications for neurosurgical intervention to attempt intraventricular silicone removal in asymptomatic patients, even with radiographic findings, since it is described as a benign finding by several authors. Symptomatic patients are rarely described, and there is no clear consensus about the management in these cases. Close follow-up and analgesia may be reasonable in stable cases; however, there are reports of migrated SiO that caused elevated intracranial pressure, in which the headaches could only be managed with ventricularperitoneal shunt [12,13,14].

The radiographic appearance of intraocular SiO is distinct from other substances by MRI. In comparison to normal vitreous, SiO is hyperintense on T1-weighted images, but it has variable intensity on T2-weighted images, an effect that has been attributed to differences in oil viscosity, degree of emulsification, and MRI sequence parameters. An MRI scan in the prone position may be used to document the buoyancy of silicone due to its lower density compared to the cerebral spinal fluid, which may aid in the differential diagnosis [11].

Previous studies tried to investigate the frequency of silicone oil extraocular migration since the prevalence of this phenomenon is not well established. Grzybowski and colleagues evaluated 19 patients with MRI at a mean of 115 days after silicone oil tamponade, demonstrating no signs of extravasation [12]. However, none of the patients in the study had an underlying risk factor for oil migration, such as glaucoma, optic atrophy, or optic pit, so the subgroup with the highest risk of this complication might have been missed [5].

Conclusions

As final considerations, the present case illustrates the importance of considering this diagnosis when encountering abnormal neuroimaging findings in a patient with a pertinent history of previous vitreoretinal surgeries. A wider knowledge of this phenomenon and intracranial silicone’s radiographic appearance may avoid unnecessary prolonged hospital stays and neurosurgical interventions.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

References

Cibis PA, Becker B, Okun E, Canaan S. The use of liquid silicone in retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1962;68:590–9.

Filippidis AS, Conroy TJ, Maragkos GA, Holsapple JW, Davies KG. Intraocular silicone oil migration into the ventricles resembling intraventricular hemorrhage: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2017;102:695 e7.

Papp A, Kiss EB, Timar O, Szabo E, Berecki A, Toth J, et al. Long-term exposure of the rabbit eye to silicone oil causes optic nerve atrophy. Brain Res Bull. 2007;74(1–3):130–3.

Ni C, Wang WJ, Albert DM, Schepens CL. Intravitreous silicone injection. Histopathologic findings in a human eye after 12 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101(9):1399–401.

Ni C, Wang WJ, Albert DM, Schepens CL. Intravitreous silicone injection histopathologic findings in a human eye after 12 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101(9):1399–401.

Kim H, Hong HS, Park J, Lee AL. Intracranial migration of intravitreal silicone oil: a case report. Clin Neuroradiol. 2016;26(1):93–5.

Agrawal R, Soni M, Biswas J, Sharma T, Gopal L. Silicone oil-associated optic nerve degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(3):429–30.

Mayl JJ, Flores MA, Stelzer JW, Liu B, Messina SA, Murray JV. Recognizing intraventricular silicone. Emerg Radiol. 2018;25(2):215–8.

Potts MB, Wu AC, Rusinak DJ, Kesavabhotla K, Jahromi BS. Seeing Floaters: a case report and literature review of intraventricular migration of silicone oil tamponade material for retinal detachment. World Neurosurg. 2018;115:201–5.

Swami MP, Bhootra K, Shah C, Mevada B. Intraventricular silicone oil mimicking a colloid cyst. Neurol India. 2015;63(4):564–6.

Boren RA, Cloy CD, Gupta AS, Dewan VN, Hogan RN. Retrolaminar migration of intraocular silicone oil. J Neuro Ophthalmol. 2016;36(4):439–47.

Kiilgaard JF, Milea D, Logager V, la Cour M. Cerebral migration of intraocular silicone oil: an MRI study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(6):522–5.

Chen JX, Nidecker AE, Aygun N, Gujar SK, Gandhi D. Intravitreal silicone oil migration into the subarachnoid space and ventricles: a case report and review of literature. Eur J Radiol. 2011;78:e81–8.

Hruby PM, Poley PR, Terp PA, Thorell WE, Margalit E. Headaches secondary to intraventricular silicone oil successfully managed with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013;7(3):288–90.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TJMMM and GAVJ contributed to designing and writing the manuscript. PHH and HML collected, analyzed, and interpreted the patient’s clinical data. AMVG contributed to writing and also critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mazzeo, T.J.M.M., Jacob, G.A.V., Horizonte, P.H. et al. Intraocular silicone oil brain migration associated with severe subacute headaches: a case report. Int J Retin Vitr 7, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-020-00273-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-020-00273-6