Abstract

Fluorescence and luminescence are widespread optical phenomena exhibited by organisms living in terrestrial and aquatic environments. While many underlying mechanistic features have been identified and characterized at the molecular and cellular levels, much less is known about the ecology and evolution of these forms of bioluminescence. In this review, we summarize recent findings in the evolutionary history and ecological functions of fluorescent proteins (FP) and pigments. Evidence for green fluorescent protein (GFP) orthologs in cephalochordates and non-GFP fluorescent proteins in vertebrates suggests unexplored evolutionary scenarios that favor multiple independent origins of fluorescence across metazoan lineages. Several context-dependent behavioral and physiological roles have been attributed to fluorescent proteins, ranging from communication and predation to UV protection. However, rigorous functional and mechanistic studies are needed to shed light on the ecological functions and control mechanisms of fluorescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The emission of light by living organisms relies on two primary mechanisms; natural luminescence, based on endogenous chemical reactions, and fluorescence, in which absorbed light is converted into a longer wavelength. The first observations of luminescence were made almost a century ago, when several species of hydromedusae—e.g., Aequorea forskalea, Mitrocoma cellularia, Phialidium gregarium, Stomatoca atra, and Sarsia rosaria—were illuminated with UV light [1, 2]. Later studies of the luminescent properties of the hydrozoan medusa Aequorea victoria led to the isolation of aequorin, a chemiluminescent protein that emits blue light (reviewed in [3]). The green fluorescent protein (GFP) was identified as a by-product of aequorin, and was shown to release fluorescent photons after absorbing electromagnetic energy [4] (see glossary in Table 1). The discoverers of GFP showed that calcium ion binding triggers the emission of blue light from aequorin at 470 nm, in turn prompting an energy transfer to GFP, which emits light at a longer wavelength, giving off green fluorescence at 508 nm [3, 4].

Green fluorescent protein consists of a single polypeptide chain of 238 amino acids in length, and does not require a cofactor [5]. The chromophore, the structural feature of GFP responsible for color emission, is formed by the autocatalytic cyclization of the tripeptide 65-SYG-67 [3]. Members of the GFP family constitute a distinct protein class, all of which share similar structures [6]. After the cloning of the GFP gene [7] and the in vivo demonstration that its recombinant expression in Escherichia coli and Caenorhabditis elegans induces fluorescence [8], interest in and applications of GFP have continued to increase within the scientific community. Originally used as a reporter gene for tracing proteins, organelles, and cells, non-invasive GFP tagging has become a routine tool in scientific research for a variety of experimental approaches, such as gene reporting, drug screening, and labeling. In parallel to the discovery of new wild-type fluorescent proteins (FPs), the hunt to engineer novel FP mutants has led to modifications of their chemical properties in an effort to broaden their potential applications in cell biology and biomedicine [9]. Beyond the biotechnological revolution prompted by the discovery of FPs, no mechanistic explanation has been proposed for the presence of fluorescence in nature. Recent findings relating to new FPs have prompted investigations in novel research directions, such as evolutionary ecology, as little is known about the eco-physiological role of fluorescence in nature. In the present review, we present and discuss several perspectives, such as the phylogenetic distribution of fluorescence in nature, the expansion of FPs in the tree of life, pigment-generated fluorescence, and the ecological functions of fluorescence in aquatic and terrestrial environments.

Differences between marine fluorescence and luminescence

In the sea, the sources of light energy are sunlight, moonlight, and luminescence. Only a small fraction of daylight penetrates the ocean’s depths, becoming progressively dimmer before resolving to a uniform blue spectrum (470–490 nm) light. Orange-red light penetrates only to a depth of 15 m and ultraviolet light to 30 m [10]. Bioluminescence is the emission of visible light by an organism resulting from luciferin oxidation under the control of luciferase. Instead, photoproteins, which are the primary substrates of the light-emitting reactions of various bioluminescent organisms in diverse phyla, do not require luciferase enzyme activity [11], but instead rely on Ca2+ or superoxide radicals and O2 to trigger bioluminescence. This mechanism is the primary source of biogenic emission of light in the ocean from the epipelagic to the abyssal zone, in regions from the poles to the equator [12]. For many marine species, the primary visual stimulus comes from biologically generated light rather than from sunlight. Given its widespread distribution, bioluminescence is clearly a predominant form of communication in the sea, with important effects on diurnal vertical migration, predator–prey interactions, and the flow of material through the food web [12].

Biofluorescence is a phenomenon dependent on external light, in which a fluorophore converts absorbed short-wavelength light to a longer wavelength. In other words, incident light is re-emitted at a longer, less energetic wavelength, therefore with low energy conversion efficiency. Natural fluorescence may derive not only from fluorescence-emitting proteins, but also from organic pigments, such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, flavonoids, pterins, or minerals, such as zinc, strontium, aluminium, selenium, and cadmium, that are able to emit light at similar wavelengths (Table 2 and Fig. 1) [33]. In terrestrial animals, specific compounds, such as chemical derivatives of the organic substance coumarin, seem to be at the origin of fluorescence observed in the cuticles of some arthropods (e.g., spiders and scorpions) [26, 34]. These biotic and abiotic substances may also be phosphorescent under UV light, a fluorescence-like physical process characterized by a longer emission time course. Especially in aphotic habitats, fluorescence and luminescence may coexist and interact within the same organism, in which the latter acts as light energy source for fluorescence since some luminescent compounds (e.g., those in dinoflagellates) may also be autofluorescent [35]. By virtue of this coexistence, photophores (luminescent organs) often convert their naturally blue luminescent light into green light by using GFP [13, 20]. This is also the case of chromatophores, which are dermal cells that mediate color changes in vertebrates (see glossary in Table 1). In fish, for example, these cells are specialized in the synthesis and storage of light-absorbing pigments [36].

Samples of GFP in cnidarians and pigment generated by fluorescent organisms from the Gulf of Naples (Italy). a–f: Cnidarian hydrozoans, Clytia hemisphaericaa–c and Obelia sp. d–f; g–i: Phoronida, actinotroch larva of unknown species; j–o: Arthropoda, unknown ostracod species j–l and unknown crustacean species m-o

Fluorescent proteins in the tree of life

The evolutionary origin of FP genes in metazoans remains subject to debate. Canonical GFP orthologs have been identified only in the phyla Cnidaria, Arthropoda, and Chordata, suggesting the presence of GFP in the last common ancestor of all metazoans (Fig. 1). Recently, GFP-like genes have been found in transcriptomes of 30 ctenophores, which is relevant to their early divergent phylogenetic position [37]. Although one of them was initially described as a fluorescent protein [38], a deeper study indicated that fluorescence in the ctenophore was not intrinsic, but originated from a siphonophore it had consumed [37].

For the present review, we performed an extensive search for well-annotated transcriptomes and genomes of sponges, nematodes, annelids, molluscs, echinoderms, and hemichordates, but did not identify any orthologs of canonical GFPs. This suggests that independent gene loss events occurred in the evolutionary history of several animal clades. An alternative phylogenetic scenario capable of explaining the scattered phylogenetic distribution of GFPs would involve independent horizontal gene transfer events, probably through diet; this possibility requires further investigation [39]. Two important evolutionary events appear to have occurred chordate clade: the loss of GFP representatives in Olfactores (comprising tunicates and vertebrates) and, in contrast, extraordinary gene expansion recently detected in cephalochordates (Fig. 2). In fact, 21 expressed GFPs have been identified in the amphioxus Branchiostoma lanceolatum, although the significance of this extensive number of GFPs requires further functional clarification [6, 40].

Distribution of fluorescent proteins in metazoan. Canonical GFPs have been found in cnidarian, arthropods and cephalochordates, supporting the hypothesis of a common metazoan ancestral origin. Color expansion is present in cnidarians and has been recently showed in cephalochordates as well. Furthermore, two other FPs, not related to GFP, have been characterized in vertebrates: UnaG and Sandercyanin

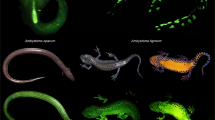

Recently, new FP families have been characterized in vertebrates bearing different features in comparison with canonical GFP proteins. For instance, a blue fluorescent protein named Sandercyanin was first isolated almost a decade ago from the freshwater walleye (Sander vitreus), a fish founds in the lakes of North America (Fig. 1). This is the first FP described with blue absorption and far-red emission under UV radiation [23]. Furthermore, a non-GFP green fluorescent protein belonging to the fatty-acid-binding protein family (FABP) was isolated from the muscles of the freshwater eel Anguilla japonica (Fig. 2) [22]. This protein, named UnaG (unagi is the Japanese name for this species of eel), triggers bright green fluorescence through coupling with bilirubin [22]. Two novel brightly fluorescent FABP proteins originating from a gene duplication event have also been characterized in the false moray eel (Kaupichthys hyoproroides) [41]. Since this cryptic eel occupies a nearly monochromatic marine environment predominated by blue wavelengths, further analyses are needed to determine the ecological function of this green emission [41].

Finally, fluorescence has been recently identified in two catshark species, Cephaloscyllium ventriosum (swell shark) and Scyliorhinus rotifer (chain catshark), in which light emission from the skin is essentially due to bromo-kynurenin yellow metabolites. This discovery raises new questions about the diversity of fluorescence sources in nature and the ecological roles in vertebrates [42].

A wide range of color-emitting GFPs characterize the phylum Cnidaria, in particular in anthozoans (sea anemones and corals). More than two decades ago, the DsRed protein was discovered in non-bioluminescent reef coral species of the genus Discosoma [14]. Chromophore synthesis, responsible of the color of the protein, is a molecular process that requires genomic stability, as any mutation disrupting the autocatalytic reaction in DsRed would convert it into green protein [43]. Indeed, at least seven different mutant variants of DsRed emitting in the green range have been generated by random and site-specific mutagenesis events [44, 45].

Anthozoan FPs have been engineered to produce photoactivable FPs (PAFPs) generating huge light-induced spectral changes. Dendra, originally from octocoral Dendronephthya sp., was the first PAFP shown to be capable of photoconversion from green to red fluorescent states in response to either visible blue or UV-violet light [18]. In addition to its high photostability, this PAFP is easily photoactivated by ordinary 488-nm laser light. Similar to Dendra, Dronpa is a reversible bright green PAFP derived from the coral Echinophyllia sp. that shows interesting properties beyond its extreme brightness, as it can be switched on and off repeatedly with high contrast and a minimal loss in fluorescence intensity [19, 46].

While FPs have been characterized mainly in eukaryotes, interest in prokaryote orthologs has increased in the last years. A far-red Biliverdin-Binding FP (smURFP) was developed from a member of the same family as Sandercyanin derived from the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium erythraeum. Unlike Sandercyanin, smURFP fluorescence is visible without exogenous biliverdin, and is the brightest far-red/near-infrared FP created to date [24]. Bacterial fluorescence has also been a template for generating non-oxygen-dependent FPs. Flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-based fluorescent proteins (FbFPs), unlike GFPs, do not require oxygen as a cofactor to synthesize the FMN chromophore, which makes these FPs very convenient for studying anaerobic biological systems [46].

Ecological functions of fluorescence

Compared to terrestrial animals, marine organisms occupy a spectrally limited visual environment, in which their eyes are adapted to different light conditions. In particular, a topic of interest in the evolutionary and ecology fields concerns how different types of visual systems developed specific spectral receptors and pigments (allowing them to detect fluorescence). Crustaceans such as the mantis shrimp have developed a fascinating system of color vision, based on at least eight primary spectral receptors ranging from 400 to 700 nm. In the species Lysiosquillina glabriuscula it has been shown that, at depths of 20, 30, and 40 m, fluorescence contributes 9, 11, and 12% of the photons that stimulate the shorter-wavelength receptor, and 15, 22, and 30% of those stimulating the longer-wavelength receptor, respectively [47].

However, to determine whether sufficient energy is transferred in order to make a meaningful difference to the visual signal under natural lighting conditions, several optical factors such as exitance and reflectance (see glossary, Table 1) need to be calculated. In addition, fluorescence can only play a role in vision if it contributes to the total light leaving the surface and to a behavioral response; i.e., if the behavior of the viewing organism is influenced by the presence or absence of fluorescence in the subject [48]. Another key unresolved issue is whether fluorescence is sufficiently bright to be visible against the background light environment.

What are the adaptive advantages conferred by fluorescence? While it is thought that not all biofluorescence is functionally relevant, few examples of its ecological role have been described. A number of hypotheses have been advanced to explain the roles of fluorescence, alone or in combination with luminescence. These include photoprotection for stem cells, photosynthesis enhancement, predation by prey lure or distraction, and protection against oxidative stress. Below, we use a taxonomic approach to review advances in the understanding of the ecological roles of fluorescence in marine organisms.

Green fluorescent proteins and, in general, fluorescent pigments, act as a photoprotective system against damage from sunlight [49]. It has been shown that UVA and extreme photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) trigger photodamage and photoinhibition in coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis that, in severe cases, may result in coral bleaching [49, 50]. In this context, FPs histologically positioned above endosymbionts may function as an energy dispatcher through fluorescence and light scattering. In the hydrozoan A. victoria, the response to superoxide radicals was investigated by examining the protein structure of GFP. Superoxide radicals and reactive oxygen species are typically present in the hyperoxic conditions that these organisms experience during the daytime due to the photosynthetic activity of algal symbionts. It has been shown that GFP can quench (see glossary, Table 1) these superoxide radicals without altering its fluorescence properties [51], thereby providing protection from antioxidants.

Marine organisms

It is fascinating how in the deep sea, the largest habitat on earth, marine organisms can live in constant darkness without access to high-energy blue light [52], using instead luminescence as the predominant light-signaling phenomenon. It is even more fascinating that, as a consequence of the production of blue luminescent light in this habitat, fluorescence acts as an energy-collecting device that enhances photosynthesis in cnidarians [53].

The tentacles of the deep-sea anemone Cribrinopsis japonica emit green fluorescence, when excited by blue light, potentially as a lure for prey attraction [54]. Interestingly, the GFP isolated from this anemone is more stable than other GFPs; however, it is unclear whether this results from adaptation to its deep-sea habitat. The sea anemone Nematostella vectensis was the first early metazoan whose genome was sequenced, and represents a powerful model system for evolutionary development biology [55]. This species possesses seven GFP genes, of which only nvfp-7r, which codes for a red fluorescent protein (NvFP-7R), is functionally fluorescent. The transcriptional regulation of the nvfp-7r gene shows spatiotemporal complexity as well as the unexpected capacity to respond to positional information in the adult body plan [56]. Despite the current knowledge of the functional significance of red fluorescence in N. vectensis (as well as in the vast majority of fluorescent organisms), it is nonetheless based upon hypothetical reconstructions. The large toolkit of sophisticated approaches available for this species renders this small anthozoan a promising model for the acquisition of deeper insights into the role(s) of fluorescence.

The function of fluorescence in prey attraction has been assessed in a non-luminescent hydromedusa species, Olindias formosus, which possesses fluorescent and pigmented patches on the end tips of its tentacles from early development of the polyp stage. In laboratory experiments under blue light conditions, these pigmented patches attract juvenile rockfish of the genus Sebastes, which do not respond in the absence of fluorescence [57]. A similar mechanism has been observed in the siphonophore Resomia ornicephala, which possesses fluorescent tentacles that attract and capture euphausiid shrimp [58].

In the hydrozoan jellyfish Clytia hemisphaerica, the intense green fluorescence observed in the endodermal and ectodermal cells of the mouth, stomach, and gonads may have several functions, including protection of stem cells and maternal mitochondrial DNA from UV light. Each of the four GFPs (and the three aequorins) isolated in this species show life-cycle stage and tissue specificity, supporting the hypothesis that fluorescence has acquired multiple specialized roles in response to environmental (depth), physiological (life-cycle) or behavioral (spawning) conditions [59]. The siphonophore Erenna sirena is another example in nature of energy conversion from luminescence to fluorescence by creating yellow to red fishing lures (583–680 nm) on its tentacles surrounded by a luminescent photophore [60].

In the phylum Arthropoda, few copepod species exhibit luminescence, while several others, belonging to the Pontellidae and Aetideidae families, exhibit biofluorescence, which is thought to serve as a mate perception and attraction signal and/or a camouflage mechanism [20, 61]. Interestingly, the high brightness and stability and low cytotoxicity of copepod GFP proteins make these molecules particularly well-suited to a variety of molecular and biological applications [62].

Although neither stomatopod crustaceans nor mantis shrimps possess fluorescent proteins, many species display a very bright fluorescent coloration that is used in postural signaling to increase shrimp visibility when sensing a predator, for intra-species competition with other males, and in mate choice [47].

Studies on FPs in chordates provide further information about their function when compared to invertebrates. In the cephalochordates Branchiostoma floridae, Branchiostoma lanceolatum, Branchiostoma belcheri and Asymmetron lucayanum, an expansion of GFPs has been reported in the genome [6, 21, 63]. Different functions have been postulated, such as playing a role in antioxidant mechanisms by scavenging deleterious oxy-radicals, in photoprotection and attracting motile planktonic prey [6, 21]. In cartilaginous and bony fish, such as catsharks and reef fish, fluorescence may function in communication, species recognition, and camouflage [64] or it may simply be a chemical by-product of skin composition.

Green and red fluorescence have also been observed in the sea turtles Eretmochelys imbricata and Caretta caretta. Whether these originate from diet (corals, zooxanthelles) [65], or as a by-product of the chemical composition of algae growing on their shells [66] remains unclear. It is also uncertain what role fluorescence might play in a sea turtle. In the case of the loose-jaw dragonfish Malacosteus sp., the animal emits luminescent light and far-red fluorescence, which may be used in predation [67]. Most reef fish possess visual pigments ranging from UV to green wavelengths [68, 69]. Interestingly, red fluorescence has been observed in more than 180 species of marine fish [52], strongly suggesting its potential role in vision [69].

Experiments conducted on the diurnal fish Cirrhilabrus solorensis, whose visual system is receptive to deep red fluorescent coloration, have demonstrated that its strong red fluorescence emission body pattern affects male–male interaction [70]. A study on the spectral sensitivity of the goby Eviota atriventris revealed that this fish possesses long-wavelength visual pigments, making it physiologically sensitive to red fluorescent coloration [71]. Lending further weight to this hypothesis, yellow intraocular filters have been found in reef fish, sharks, lizardfish, scorpionfish, and flatfish, which could enable them to detect fluorescence [72]. It has also been demonstrated that sharks and rays are capable of visualizing their own fluorescence, showing sexually dimorphic fluorescent body patterns, which is suggestive of a function in communication or species-recognition role [64].

Nevertheless, despite several attempts, no sufficient experimental studies have clarified the functional and behavioral link between fluorescence and vision in organisms with complex visual systems [69].

Terrestrial organisms

Fluorescence produced by fluorescent metabolic chemical by-products is also observed in many terrestrial organisms. Several recent studies have suggested ecological and behavioral roles similar to those highlighted in marine organisms. In amphibians, the tree frog Hypsiboas punctatus emits hyloins, fluorescent compounds secreted from the lymph and gland nodes [31]. This suggests that fluorescence is part of the integumentary pigment system in this amphibian, representing a novel extra-chromatophore source of coloration. In low-light conditions, frog fluorescence accounts for 18–29% of the total emerging light comprising fluoresced and reflected photons. This confers greater brightness to H. punctatus and matches the sensitivity of night vision in this clade.

Another interesting example is represented by butterfly wings, which possess an intrinsic controlled system that is remarkably similar to recent LED technology, utilizing a photon crystal-like structure capable of producing directed fluorescence [73].

Behavioral experiments performed in arthropods and chordates underline the potential role of fluorescence in communication. In fact, the fluorescent plumage in the parrot Melopsittacus undulate was shown to have behavioral implications in mate selection, rather than in social communication [74]. In fact, female and male parrots exhibit significant preferences for fluorescent birds of the opposite sex [75].

The jumping spider Cosmophasis umbratica has been shown to interact differently in the presence of UV reflectance or UV-induced fluorescence while testing sex-specific courtship signaling [76]. Males present UV-reflective patches of scales on the face and body that are shown during conspecific posturing [77]. These patches are lacking in females, which instead have palps with a UV-excited bright green fluorescence that are absent in males. During the experiment, female spiders made a postural response to male courtship under full-light spectrum, while they did not respond or turned away without UV. Similarly, males ignored non-fluorescing females. The courtship responses of the spiders were an effect of sexual coloration instead of behavioral changes. To determine this, the behavioral responses of individuals of one sex under full-spectral light were compared when the partner of the opposite sex was illuminated with UV-deficient light. Most UV-irradiated male spiders that courted fluorescent females failed to do so when the female lacked fluorescence even though her response was the same as under normal light.

Desert scorpions exhibit blue/green fluorescence under UV light in laboratory conditions, although this phenomenon does not manifest in natural daylight conditions. Beta-carboline, a tryptophan derivative molecule is responsible for the fluorescence in the cuticle of scorpions (Table 2) [26]. Although it has been hypothesized that fluorescence in scorpions may serve as a prey lure, it is clear that the formation of this substance on the cuticle of this animal serves no function [78].

Finally, it has been recently shown that tubercles protruding from the skull of chameleons reveal fluorescence upon short-wavelength UV-irradiation; this may play a role in species recognition [79]. Emission signals corresponding to deep blue are reasonably rare in tropical forests; this form of biofluorescence thus appears to be a distinct signal against the green vegetation background reflectance [79].

Fluorescence plays roles in terrestrial animals as well as plants, such as the carnivorous Nepenthes, Sarracenia, and Dionaea. Preliminary studies have quantitatively measured fluorescence in flowers in several species and concluded that its relevance for communication is negligible [80]. However, more recently, blue fluorescence emission at the catch sites of these plants was detected, suggesting that it could play a role in attracting arthropod prey compared to non-illuminated plants [81]. In the yellow flowers of the plant Portulaca grandiflora, the pigment betaxanthin is at the origin of green emission when the flower is excited by blue light (Table 2) [32]. The flower exhibits natural yellow coloration; its brightness may be increased by this fluorescent pigment at a particular wavelength, making the flower more visible to pollinators.

Conclusion and perspectives

Both fluorescence and luminescence are prevalent optical processes present in nature and crucial for species communication and predator–prey interactions, and may coexist or cooperate in many species, such as deep-sea animals. The discovery of GFP in 1962 in the cnidarian jellyfish A. victoria and the subsequent characterization of numerous GFPs in several taxa have prompted research on biotechnological applications. More recently, orthologs of GFP have been identified in arthropods and chordates; nevertheless, the evolutionary and ecological significance of fluorescence requires substantial further study.

Recently, the exciting discovery of novel types of fluorescent proteins in vertebrates (i.e. UnaG and Sandercyanin) has led to novel evolutionary insights, given that until recently only GFPs and GFP-like proteins were thought to support fluorescence. The identification of yellow fluorescent metabolites in sharks has also opened new avenues of inquiry into their roles in central nervous system function, photoprotection, and resilience to microbial infections. For example, genome editing of fluorescent proteins in a living model organism such as Clytia hemisphaerica may be highly informative in order to assess its biological function. Although its roles in communication, predation, and camouflage in several taxa are widely accepted in the scientific community, evidence for and interpretation of additional functions require stronger scientific support. It will also be crucial to conduct further functional studies of fluorescence in both terrestrial and marine species to assess whether the emission of fluorescence is quantitatively significant in natural environments, which is necessarily different from that under laboratory conditions.

Finally, our understanding of the role of fluorescence in animal vision is in its early stages, as seen from a few recent studies in reef and deep-sea fish. Further research is also needed to clarify the anatomy of the visual apparatus, which we did not examine in this review, and the molecular toolkits involved in color, contrast, and fluorescence detection, in order to shed light on these unresolved questions.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Harvey EN. Studies on bioluminescence. Biol Bull 1921;41:280–287. https://doi.org/10.2307/1536528.

Davenport D, Nicol JAC. Luminescence in hydromedusae. Proc R Soc London Ser B 1955;144:399–411. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1955.0066.

Shimomura O. Structure of the chromophore of Aequorea green fluorescent protein. FEBS Lett 1979;104:220–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(79)80818-2.

Shimomura O, Johnson FH, Saiga Y. Extraction, purification and properties of Aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea J Cell Comp Physiol 1962;59:223–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.1030590302.

Hink MA, Griep RA, Borst JW, Van Hoek A, Eppink MHM, Schots A, et al. Structural dynamics of green fluorescent protein alone and fused with a single chain Fv protein. J Biol Chem 2000;275:17556–17560. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M001348200.

Yue JX, Holland ND, Holland LZ, Deheyn DD. The evolution of genes encoding for green fluorescent proteins: insights from cephalochordates (amphioxus). Sci Rep 2016;6:28350. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28350.

Prasher DC, Eckenrode VK, Ward WW, Prendergast FG, Cormier MJ. Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green-fluorescent protein. Gene. 1992;111:229–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1119(92)90691-H.

Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W, Prasher D. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8303295.

Mocz G. Fluorescent proteins and their use in marine biosciences, biotechnology, and proteomics. Mar Biotechnol. 2007;9:305–328. doi :10.1007/s10126-006-7145-.

Marshall J. Vision and lack of vision in the ocean. Curr Biol 2017;27:R494–R502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.012.

Shimomura O. Bioluminescence in the sea: photoprotein systems. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1985;39:351–72.

Haddock SHD, Moline MA, Case JF. Bioluminescence in the sea. Annu Rev Mar Sci 2010;2:443–493. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028.

Lewis M. Fluorescent proteins and chromoproteins in phylum: Cnidaria. 2012. The Plymouth Student Scientist.

Matz MV., Fradkov AF, Labas YA, Savitsky AP, Zaraisky AG, Markelov ML, et al. Fluorescent proteins from nonbioluminescent Anthozoa species. Nat Biotechnol 1999;17:969–973. https://doi.org/10.1038/13657.

Labas YA, Gurskaya NG, Yanushevich YG, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov SA, et al. Diversity and evolution of the green fluorescent protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:4256–4261. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.062552299.

Schnitzler CE, Keenan RJ, McCord R, Matysik A, Christianson LM, Haddock SHD. Spectral diversity of fluorescent proteins from the anthozoan Corynactis californica. Mar Biotechnol 2008;10:328–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-007-9072-7.

Ando R, Hama H, Yamamoto-Hino M, Mizuno H, Miyawaki A. An optical marker based on the UV-induced green-to-red photoconversion of a fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:12651–12656. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.202320599.

Gurskaya NG, Verkhusha VV, Shcheglov AS, Staroverov DB, Chepurnykh TV, Fradkov AF, et al. Engineering of a monomeric green-to-red photoactivatable fluorescent protein induced by blue light. Nat Biotechnol 2006;24:461–465. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1191.

Ando R. Regulated fast Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling observed by reversible protein highlighting. Science. 2004;306:1370–1373. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102506.

Shagin DA, Barsova EV, Yanushevich YG, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, Labas YA, et al. GFP-like proteins as ubiquitous metazoan superfamily: evolution of functional features and structural complexity. Mol Biol Evol 2004;21:841–850. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msh079.

Bomati EK, Manning G, Deheyn DD. Amphioxus encodes the largest known family of green fluorescent proteins, which have diversified into distinct functional classes. BMC Evol Biol 2009;9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-9-77.

Kumagai A, Ando R, Miyatake H, Greimel P, Kobayashi T, Hirabayashi Y. A bilirubin-inducible fluorescent protein from eel muscle. Cell. 2013;153:1602–1611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.038.

Ghosh S, Yu C-L, Ferraro DJ, Sudha S, Pal SK, Schaefer WF, et al. Blue protein with red fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:11513–11518. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525622113.

Rodriguez EA, Tran GN, Gross LA, Crisp JL, Shu X, Lin JY, et al. A far-red fluorescent protein evolved from a cyanobacterial phycobiliprotein. Nat Methods 2016;13:763–769. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3935.

Chayen NE, Cianci M, Grossmann JG, Habash J, Helliwell JR, Nneji GA, et al. Unravelling the structural chemistry of the colouration mechanism in lobster shell. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2003;59 Pt 12:2072–2082. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444903025952.

Stachel SJ, Stockwell SA, Van Vranken DL. The fluorescence of scorpions and cataractogenesis. Chem Biol 1999;6:531–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80085-4.

Stradi R, Pini E, Celentano G. The chemical structure of the pigments in Ara Macao plumage. Physiology. 2001;130:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00402-x.

Thomas DB, McGoverin CM, McGraw KJ, James HF, Madden O. Vibrational spectroscopic analyses of unique yellow feather pigments (spheniscins) in penguins. J R Soc Interface 2013;10:20121065. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.1065.

Le Guyader S, Jesuthasan S. Analysis of xanthophore and pterinosome biogenesis in zebrafish using methylene blue and pteridine autofluorescence. Pigment Cell Res 2002;15:27–31. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.00045.x.

Comfort A. The pigmentation of Molluscan shells. Biol Rev 1951;26:285–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1951.tb01358.x.

Taboada C, Brunetti AE, Pedron FN, Carnevale Neto F, Estrin DA, Bari SE, et al. Naturally occurring fluorescence in frogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:3672–3677. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701053114.

Gandía-Herrero F, Escribano J, García-Carmona F. Betaxanthins as pigments responsible for visible fluorescence in flowers. Planta. 2005;222:586–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-005-0004-3.

Johnsen S. The optics of life a Biologist’s guide to light in nature. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 2012.

Andrews K, Reed SM, Masta SE. Spiders fluoresce variably across many taxa. Biol Lett 2007;3:265–267. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2007.0016.

Johnson CH, Inoué S, Flint A, Hastings JW. Compartmentalization of algal bioluminescence: autofluorescence of bioluminescent particles in the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax as studied with image-intensified video microscopy and flow cytometry. J Cell Biol 1985;100:1435–1446. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.100.5.1435.

Leclercq E, Taylor JF, Migaud H. Morphological skin colour changes in teleosts. Fish Fish 2009;11:159–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00346.x.

Francis WR, Christianson LM, Powers ML, Schnitzler CE, Haddock SHD. Non-excitable fluorescent protein orthologs found in ctenophores. BMC Evol Biol 2016;16:167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0738-5.

Haddock SHD, Mastroianni N, Christianson LM. A photoactivatable green-fluorescent protein from the phylum Ctenophora. Proc Biol Sci 2010;277:1155–1160. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1774.

Deheyn DD, Kubokawa K, Mccarthy JK, Murakami A, Rouse GW, Holland ND. Endogenous green fluorescent protein in Amphioxus (GFP). Biol Bull 2007;213:95–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/25066625.

Baumann D, Cook M, Ma L, Mushegian A, Sanders E, Schwartz J, et al. A family of GFP-like proteins with different spectral properties in lancelet Branchiostoma floridae. Biol Direct 2008;3:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6150-3-28.

Gruber DF, Gaffney JP, Mehr S, Desalle R, Sparks JS, Platisa J, et al. Adaptive evolution of eel fluorescent proteins from fatty acid binding proteins produces bright fluorescence in the marine environment. PLoS One 2015;10:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140972.

Park HB, Lam YC, Gaffney JP, Weaver JC, Krivoshik SR, Hamchand R, et al. Bright green biofluorescence in sharks derives from bromo-kynurenine metabolism. iScience 2019;19:1291-1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.07.019.

Terskikh A, Fradkov A, Ermakova G, Zaraisky A, Tan P, Kajava AV, et al. “Fluorescent timer”: protein that changes color with time. Science. 2000;290:1585–1588. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5496.1585.

Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Biochemistry, mutagenesis, and oligomerization of DsRed, a red fluorescent protein from coral. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:11984–11989. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.22.11984.

Chudakov D, Matz M, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov K. Fluorescent proteins and their applications in imaging living cells and tissues. Physiol Rev 2010;90:1103–1163. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00038.2009.

Drepper T, Eggert T, Circolone F, Heck A, Krauß U, Guterl JK, et al. Reporter proteins for in vivo fluorescence without oxygen. Nat Biotechnol 2007;25:443–445. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1293.

Mazel CH, Cronin TW , RL Caldwell, NJ Marshall. Flourescent enhancement of signalling in a mantis shrimp Science 2004;303:51. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089803.

Mazel C. Method for determining the contribution of fluorescence to an optical signature, with implications for postulating a visual function. Front Mar Sci 2017;4: 266. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00266.

Salih A, Larkum A, Cox G, Kühl M, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Fluorescent pigments in corals are photoprotective. Nature. 2000;408:850–853. https://doi.org/10.1038/35048564.

Roth MS, Latz MI, Goericke R, Deheyn DD. Green fluorescent protein regulation in the coral Acropora yongei during photoacclimation. J Exp Biol 2010;213:3644–3655. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.040881.

Bou-Abdallah F, Chasteen ND, Lesser MP. Quenching of superoxide radicals by green fluorescent protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1760:1690–1695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.08.014.

Sparks JS, Schelly RC, Smith WL, Davis MP, Tchernov D, Pieribone VA, et al. The covert world of fish biofluorescence: a phylogenetically widespread and phenotypically variable phenomenon. PLoS One 2014;9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083259.

Matz MV, Labas YA, Ugalde J. Evolution of function and color in GFP-like proteins. Green Fluoresc Protein Prop Appl Protoc Second Ed 2005;47:139–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471739499.ch7.

Tsutsui K, Shimada E, Ogawa T, Tsuruwaka Y. A novel fluorescent protein from the deep-sea anemone Cribrinopsis japonica (Anthozoa: Actiniaria). Sci Rep 2016;6:23493. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23493.

Putnam NH, Srivastava M, Hellsten U, Dirks B, Chapman J, Salamov A, et al. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization. Science. 2007;317:86–94. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1139158.

Ikmi A, Gibson MC. Identification and in vivo characterization of NvFP-7R, a developmentally regulated red fluorescent protein of Nematostella vectensis. PLoS One 2010;5:e11807. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011807.

Haddock SHD, Dunn CW. Fluorescent proteins function as a prey attractant: experimental evidence from the hydromedusa Olindias formosus and other marine organisms. Biol Open 2015;4:1094–1104. https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.012138.

Pugh PR, Haddock SHD. Three new species of remosiid siphonophore (Siphonophora: Physonectae). J Mar Biol Assoc United Kingdom 2010;90:1119–1143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315409990543.

Fourrage C, Swann K, Garcia JRG, Campbell AK, Houliston E. An endogenous green fluorescent protein-photoprotein pair in clytia hemisphaerica eggs shows co-targeting to mitochondria and efficient bioluminescence energy transfer. Open Biol 2014;4 https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.130206.

Haddock SHD. Bioluminescent and red-fluorescent lures in a Deep-Sea Siphonophore. Science. 2005;309:263–263. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110441.

Hunt ME, Scherrer MP, Ferrari FD, Matz MV. Very bright green fluorescent proteins from the pontellid copepod Pontella mimocerami. PLoS One 2010;5:3–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011517.

Neckles VN, Morton MC, Holmberg JC, Sokolov AM, Nottoli T, Liu D, et al. A transgenic inducible GFP extracellular-vesicle reporter (TIGER) mouse illuminates neonatal cortical astrocytes as a source of immunomodulatory extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep 2019;9:3094. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39679-0.

Li G, Zhang QJ, Zhong J, Wang YQ. Evolutionary and functional diversity of green fluorescent proteins in cephalochordates. Gene. 2009;446:41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2009.07.003.

Gruber DF, Loew ER, Deheyn DD, Akkaynak D, Gaffney JP, Smith WL, et al. Biofluorescence in Catsharks (Scyliorhinidae): fundamental description and relevance for elasmobranch visual ecology. Sci Rep 2016;6:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24751.

Obura DO, Harvey A, Young T, Eltayeb MM, von Brandis R. Hawksbill turtles as significant predators on hard coral. Coral Reefs 2010;29:759–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-010-0611-8.

Gruber DF, Sparks JS. First observation of fluorescence in marine turtles. Am Museum Novit 2015; 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1206/3845.1.

Douglas RH, Partridge JC, Hynninen PH. Dragon fish see using chlorophyll. Nature. 1998;393:423–424. https://doi.org/10.1038/30871.

Losey GS, Cronin TW, Goldsmith TH, Hyde D, Marshall NJ, McFarland WN. The UV visual world of fishes: a review. J Fish Biol 1999;54:921–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00848.x.

Gerlach T, Sprenger D, Michiels NK. Fairy wrasses perceive and respond to their deep red fluorescent coloration. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2014;281. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.0787.

Warrant EJ, Locket NA. Vision in the deep sea. Biol Rev 2004;79:671–712. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793103006420.

Michiels NK, Anthes N, Hart NS, Herler J, Meixner AJ, Schleifenbaum F, et al. Red fluorescence in reef fish: a novel signalling mechanism? BMC Ecol 2008;8:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6785-8-16.

Heinermann PH. Yellow intraocular filters in fishes. Exp Biol. 1984;43:127–47.

Vukusic P, Hooper I. Directionally controlled fluorescence emission in butterflies. Science 2005,310:1151–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science1116612.

Fox HM, Vevers G. The nature of animal colours. University of Washington Press, 1960.

Arnold KE, Owens PF, Marshall NJ. Fluorescent signaling in parrots. Science. 2002;295:92. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.295.5552.92.

Lim MLM, Land MF, Li D. Sex-specific UV and fluorescence signals in jumping spiders. Science. 2007;315:481–481. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1134254.

Lim MLM, Li D. Extreme ultraviolet sexual dimorphism in jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae). Biol J Linn Soc 2006;89:397–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2006.00704.x.

Kloock CT. Aerial insects avoid fluorescing scorpions. Euscorpius. 2005. https://doi.org/10.18590/euscorpius.2005.vol2005.iss21.1.

Prötzel D, Heß M, Scherz MD, Schwager M, Padje a van’t, Glaw F. Widespread bone-based fluorescence in chameleons Sci Rep 2018;8:698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-19070-7.

Iriel A, Lagorio MG. Is the flower fluorescence relevant in biocommunication? Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:915–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-010-0709-4.

Kurup R, Johnson AJ, Sankar S, Hussain AA, Kumar CS, Sabulal B. Fluorescent prey traps in carnivorous plants. Plant Biol 2013;15:611–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00709.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Francesca Strano for lovely discussions on an early version of the project. We would like to thank Eva Jimenez-Guri for her critical reading of the manuscript and Christopher Bowkett for English proofreading. Marie-Lyne Macel was supported by SZN OU PhD fellowship.

Funding

This work was performed under the TERABIO Project (2014) of the Italian MIUR (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. and D’A.S. conceived the review project. M.M., P.S. and D’A.S. wrote the manuscript. All the authors edited the manuscript and approved the final version. D’A.S. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Macel, ML., Ristoratore, F., Locascio, A. et al. Sea as a color palette: the ecology and evolution of fluorescence. Zoological Lett 6, 9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-020-00161-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-020-00161-9