Abstract

Background

Postpartum contraceptive discontinuation refers to cessation of use following initiation after delivery within 1 year postpartum. Discontinuation of use has been associated with an increased unmet need for family planning that leads to high numbers of unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortion or mistimed births. There is scant information about contraceptive discontinuation and its predictors among postpartum women in Tanzania. This study aimed to determine predictors of contraception discontinuation at 3, 6, 12 months postpartum among women of reproductive age in Arusha city and Meru district, Tanzania.

Methods

This was an analytical cross-sectional study which was conducted in two district of Arusha region (Arusha city and Meru district respectively). A multistage sampling technique was used to select 13 streets of the 3 wards in Arusha City and 2 wards in Meru District. A total of 474 women of reproductive age (WRAs) aged 16–44 years residing in the study areas were included in this analysis. Data analysis was performed using STATA version 15. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the factors associated with contraceptives discontinuation (at 3, 6 and 12 moths) were estimated in a multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

Overall, discontinuation rate for all methods at 3, 6, and 12 months postpartum was 11, 19 and 29% respectively. It was higher at 12 months for Lactational amenorrhea, male condoms and injectables (76, 50.5 and 36%, respectively). Women aged 40–44 years had lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months as compare to those aged 16 to 19 years. Implants and pills users had also lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation compared to injectable users at 3, 6 and 12 months respectively.

Conclusion

Lactational amenorrhea, male condoms and injectables users had the highest rates of discontinuation. Women’s age and type of method discontinued were independently associated with postpartum contraceptive discontinuation. Addressing barriers to continue contraceptive use amongst younger women and knowledge on method attributes, including possible side-effects and how to manage complications is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contraceptive discontinuation is defined as starting contraceptive use and then stopping for any reason while still at risk of an unintended pregnancy [1]. It has been reported to be higher for short-acting methods such as condoms, injectables, pills and traditional methods as they can be discontinued by the user herself compared to long- acting reversible methods such as implants and the Intrauterine device (IUD) which require a visit to facility to discontinue [1,2,3]. The method-related reasons and contraceptive failure have been reported as the predominant causes for contraceptive discontinuation [4].

Postpartum period in the first 12 months following childbirth has been associated with high unmet need for contraceptives coupled with unintended pregnancies [5]. Breastfeeding practices and beliefs about return of menses as a marker of fertility resumption during the postpartum period, makes it difficult for women to determine their fertility risk. Thus, women are less motivated to start contraceptive use while breastfeeding [6, 7]. Previous investigators have demonstrated that women who discontinue contraception use during the postpartum period may opt not to use any method (contraceptive discontinuation) or switch to different modern method (method switching) which is less effective than the previous method at preventing pregnancy, and thereby exposes women to risk of unintended pregnancy, abortions and mistimed pregnancies/births [7, 8].

Sustaining postpartum contraception use is important for woman’s fertility because it ensures optimal birth spacing, prevents unintended pregnancies, abortion and has an impact on infant and child survival [9]. Examining postpartum contraceptive discontinuation will shed a light on the knowledge gaps in contraceptive use such as trends and determinants for contraceptive discontinuation, and will help in reducing unmet need for family planning [10]. It will also provide evidence for areas that require coordinated efforts between different stakeholders involved in family planning programs and the government. This will help to improvement quality of services for family planning and reduces the discontinuation postpartum contraception.

Previous studies from developing countries showed that, on average, 19–64% of women discontinued using reversible contraceptive methods by the 12th month of use [4, 11]; [12,13,14,15]. The discontinuation rate for condoms within the first 12 months is higher than intrauterine devices (50% vs 13%, respectively), and up to 40% higher for other methods such as pill, injectable, periodic abstinence and withdrawal [3, 4, 16]. Contraceptive discontinuation among women with no desire to get pregnant increases the risk for unwanted pregnancies [8]. This reflects a failure of family planning programs and services [3, 4, 17,18,19].

According to Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey, only 15.5 and 22.4% of women reported using modern contraceptive methods at 3 months and 12 months post-delivery respectively, especially during postnatal visit probably due to contraceptive counselling [20]. A cohort study conducted in Northern Tanzania among 5284 pregnant women who were followed from 6 to 15 months postpartum, reported that 34% of women initiated contraceptive use during the postpartum period and 25% of the participants started at 7 months postpartum [21]. Authors in this study noted that 18.8% of contraceptive users discontinued at 15 months postpartum. The reasons for contraceptive discontinuation include partner disapproval (32%), side-effects (6%), wanting a child (4%) and other reasons (37%) [21]. The most recent study in Tanzania reported that short contraceptive methods were associated with high rate of discontinuation compared to long term acting contraceptives [13].

There is scant information on contraceptive discontinuation rates, patterns and associated factors post-delivery. This study aimed to determine predictors of contraception discontinuation at 3, 6, 12 months postpartum among women of reproductive age in Arusha city and Meru district, Tanzania.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was conducted in two districts of Arusha region (Arusha city and Meru district respectively) from December 2017–June 2018.

Study population, sample size and sampling method

The study sample included women of reproductive age (WRAs) aged 16–44 years who started to use family planning methods (modern/traditional) after a delivery (6 weeks) that occurred at least 12 months prior to the survey. Multistage cluster sampling with probability proportional to size was used to draw respondents from 13 streets (i.e. 3 wards) in Arusha City and 2 wards in Meru District. The details of the sampling procedures have been described elsewhere [15, 22]. A contraceptive calendar is a contraceptive history collected for each woman who, or whose husband, was not sterilized at the calendar’s start. The data were recorded in a calendar matrix, consisting of rows and columns, with each row of the calendar representing a particular month. The sample size was estimated based on number of events included in the contraceptive calendar, which included retrospectively reported month-by-month during 31 months before the interview. A total of 12,203 contraceptive use events were recorded during the study period. We excluded 3216 episodes which started prior to the calendar period of 31 months before the survey; 2883 episode because no birth within 31 month; 2211 episode because the episode started before the latest birth; 2494 episode because no method used, birth, termination, or pregnancy; 184 events during 0-3 months before the survey [methods unknown (n = 142) & sterilization/other (n = 42)]. The remaining 1215 episodes of use within the last 3 to 28 months prior to interview constituted the final sample size (Fig. 1).

Study variables

The main outcome was contraceptive discontinuation after starting to use of contraceptive at three time points; 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months post-delivery. The independent variables were selected based on the previous studies. These include sociodemographic characteristics: maternal age, maternal education and wealth index. Women were asked of the number of antenatal care (ANC) visits during the last pregnancy, number of months since birth to first family planning use, received contraceptive counseling during ANC or PNC visits and attendance of postnatal care after last delivery. The type of contraceptive methods used were IUD, pills, male condoms, injectables, implant, rhythm and withdrawal. Women were also asked for the reasons related to discontinuation of modern contraceptive.

Data collection methods

Data collection was conducted through face-to-face interviews using questionnaire administered using tablets. A team of trained research assistants including medical doctors, statisticians, demographers and social scientist were used to collect information from the participants. A standardized questionnaire in Kiswahili language which was adapted from the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS) 2015–2016 [12] was used to collect information from the study participants for household survey to meet the WIE objectives. These variables includes women age, education level, marital status, area of residence, wealth index, utilisation of contraceptive methods, cost to access the family planning services, type of facility, distance to health facility, type of contraceptive used and availability of family planning commodities to mention a few.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using STATA version 15. Descriptive statistics were summarized using frequency and proportions for categorical variables. The percentage of women who had discontinued their method of contraception at 3, 6 and 12 months were reported. Adjusted Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the factors associated with contraceptive discontinuation were estimated in a multivariable logistic regression model. The correlation between discontinuation at certain time (3, 6, and 12 months) with sociodemographic characteristics were separately evaluated. We used the logistic regression because the dependent variable is a dummy variable (discontinued at 3, 6, or 12 months). Independent variables we used for the regression analysis were reported in Table 1. Only variables which were significant in the bivariate analysis were included in the final model.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

We have a total of 1215 episodes from the calendar data (Table 1). About one third of all episodes (31%) were aged 25 to 29 years old. More than half (55%) of all episodes had primary education. Majority (71%) of all episodes were reported to have received family planning counselling during ANC visit and postnatal care visit (76.5%).

Contraceptive discontinuation at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum

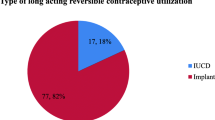

Overall, 11.5% of all episodes discontinued at 3 months. Of these, injectables, pills and male condoms were discontinued by 16, 16 and 9% of the sample respectively, while implants and IUD discontinued by 1.55 and 3.23% at 3 months. On the other hand, of the 11.5% episodes discontinued at 3 months, 27% were LAM users (Table 2). Likewise, there was 19.4% episodes discontinued at 6 months, where injectables, pills and male condoms were discontinued by 24.64, 25.44 and 20.37% of the sample respectively while implants and IUD accounted for 3.84 and 8.34% during the same period. At 6 months, 49% of those 19.4% episodes discontinued were LAM users (Table 3). Furthermore, about 29.4% episodes discontinued at 12 months, injectables, pills and male condoms accounted for 38.15, 36.48% and 50. 49% of the sample while implants and IUD contributed 5.11 and 9.06% at 12 months while 76.12% of 29.4% episodes discontinued at 12 months were LAM (Table 4).

Multivariable analysis for determinants of contraceptive discontinuation at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum

The determinants for contraceptive discontinuation across time points are shown in Table 5 (focusing only on the first Family Planning use since the birth). In multivariable regression model, age and type of method discontinued were independently associated with postpartum contraceptive discontinuation. Women aged 40 to 44 years had significantly lower odds [(OR: 0.118, 95% CI: 0.016, 0.883)] of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months postpartum compared to their counterparts aged 16 to 19 years of age. Furthermore, women who reported using implants had significantly lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months postpartum (OR: 0.095; 95% CI: 0.051,0.176), (OR: 0.142; 95% CI: 0.073,0.276) and (OR: 0.218; 95% CI: 0.100,0.473) respectively, compared to those using injectables. Women who reported using pills had lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months (OR: 0.527; 95% CI: 0.285, 0.975), 6 months (OR: 0.489; 95% CI: 0.246, 0.973) and 12 months (OR: 0.230; 95% CI: 0.068, 0.779) respectively compared to those who discontinued injectables. Other factors were not significantly associated with contraceptive discontinuation at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the determinants of postpartum contraceptive discontinuation at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum. Overall, 11.5% of all episodes discontinued at 3 months, 19.4% discontinued at 6 months and 29.4% discontinued at 12 months. Women aged 40 to 44 years had significantly lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months postpartum compared to their counterparts aged 16 to 19 years of age. Furthermore, women who reported using implants and pills had significantly lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months compared to injectable users.

The average number of months since child birth to first family planning use was 3.8 months, this was similar to what was observed in rural Ghana [23] where the average time of first family planning use following child birth was 3.5 months and in contrast to what was observed in Nairobi slums where initiation of contraceptives following child birth occurred 7 months after delivery [11]. The fact that women initiate contraceptive use early in our setting may be encouraging, however the type of methods used must be borne in mind because short contraceptive methods have been associated with high rate of discontinuation compared to long term acting contraceptives [13]. Thus, short-acting contraceptive methods do not guarantee adequate birth spacing and the prevention of unwanted or mistimed pregnancies.

The most common methods discontinued after postpartum initiation in this study were LAM, pill and injectable. This is consistent with the previous reports from Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) in Magu district in Tanzania [13, 20]. Our finding was different from Malawian study, where women who reported long-acting methods and injectable use at 3 months post-delivery were more likely to continue compared to those using pills, condoms, traditional methods [2]. It also differs from the South Africa that reported high rate of implant continuation at 12 months at a rate of 86% [7]. The difference in findings could be explained by the differences in characteristics between the studied population especially the cultural barriers. Furthermore, the high contraceptives discontinuation rate in our population calls for a need to provide women with education on contraception, increase access to contraceptives as these will facilitate women to have informed choice and decision towards contraceptive use. However, there may be a possibility of some women experiencing forms of coercion to adopt a LARC the immediate postpartum period and choosing later to have the method removed.

The lower odds of postpartum discontinuation among women aged 40–44 years in our study is consistent with previous report in Kenya by [11] where higher odds of contraceptive discontinuation among adolescent women at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months compared with the adults counterparts. Previous studies in Tanzania and Nepal also reported the effect of age and type of contraceptive methods used on post-partum contraception discontinuation [13, 24]. The high contraceptive discontinuation among young women could be explained by their fertility desire to have more children. Unlike the short-term contraceptives, the lower discontinuation rate for long-acting methods could be explained by its difficulty to remove which requires health care professionals with cost implications [25, 26].

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of this study is that, being a community-based study may reflect the representation of what is happening at the ground in the general population. We also used a rigorous data collection methods to enhance validity for observed findings. Despite its strength, some limitations which need to be taken into account while interpreting our finding. First, being a cross-sectional in nature, the study cannot establish a causal effect. Secondly, we did not collect information on sexual resumption, menstrual resumption, partners and service related factors which would further explain the methods discontinuation during the course of time.

Conclusions

Lactational amenorrhea, male condoms, injectables and pills users had the highest rates of discontinuation compared with implants and IUD users. Women aged 40 to 44 years had lower odds of postpartum contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months while implants and pills had lower odds of contraceptive discontinuation at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months. Addressing barriers to prolonged contraceptive use amongst younger women and knowledge on attributes of contraceptive methods and their potential side-effects is warranted. In addition, the programs should assist women to timely switch to a method of their preference when they discontinue the method that fail, do not meet their expectations or cause side-effects.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets from this study are readily available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

FP2020(2015) Contraceptive reasons, challenges, discontinuation: and solutions.

Kopp DM, Rosenberg NE, Stuart GS, Miller WC, Hosseinipour MC, Bonongwe P, Mwale M, Tang JH. Patterns of contraceptive adoption, continuation, and switching after delivery among Malawian women. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170284.

Thobani R, Jessani S, Azam I, Reza S, Sami N, Rozi S, Abrejo F, Saleem S. Factors associated with the discontinuation of modern methods of contraception in the low income areas of Sukh initiative Karachi: a community-based case control study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218952.

Ali MM, Cleland JG, Shah IH, World Health Organization. Causes and consequences of contraceptive discontinuation: evidence from 60 demographic and health surveys. World Health Organization; 2012. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/75429

WHO. Postpartum family planning. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;22(5):294–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/1966684.

Borda M, Winfrey W. Postpartum fertility and contraception: an analysis of findings from 17 countries. Access-fp. 2010;1(March):11–50 Available at: http://reprolineplus.org/system/files/resources/ppfp_17countryanalysis.pdf.

Singata-Madliki M, Dekile-Yonto N, Hofmeyr GJ, Lawrie TA. Postnatal contraception discontinuation: different methods, same problem. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2018;44(1):66–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-101846.

Jain AK, Winfrey W. Contribution of contraceptive discontinuation to unintended births in 36 developing countries. Stud Fam Plann. 2017;48(3):269–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12023.

World Health Organization (2013): Programming strategies for Postpartum Family Planning. Available at: https://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/93680/1/9789241506496_eng.pdf. (Accessed on 20 Mar 2017).

Jackson E, Glasier A. Return of ovulation and menses in postpartum non-lactating women: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):657–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820ce18c.

Mumah JN, Machiyama K, Mutua M, Kabiru CW, Cleland J. Contraceptive adoption, discontinuation, and switching among postpartum women in Nairobi’s urban slums. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(4):369–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00038.x.

TDHS. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2015/16 Final Report. Tanzania Demogr Heal Surv Malar Indic Surv 2015-16. 2016.

Safari W, Urassa M, Mtenga B, Changalucha J, Beard J, Church K, Zaba B, Todd J. Contraceptive use and discontinuation among women in rural North-West Tanzania. Contracept Reprod Med. 2019;4(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-019-0100-6.

Barden-O’Fallon, Speizer IS, Calhoun LM, Corroon M, et al. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0529-9.

Sato R, Elewonibi B, Msuya S, Manongi R, Canning D, Shah I. Why do women discontinue contraception and what are the post-discontinuation outcomes? Evidence from the Arusha region, Tanzania. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(1):1723321. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1723321.

Shiferaw Yideta Z, Mekonen L, Seifu W, Shine S. Contraceptive discontinuation, method switching and associated factors among reproductive age women in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia, 2013. Fam Med Med Sci Res. 2017;06(01):6–11. https://doi.org/10.4172/2327-4972.1000213.

Adal TG. Early discontinuation of long acting reversible contraceptives among married and in union women : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2017;7(1):113–8.

Do Nascimento Chofakian CB, et al. Contraceptive discontinuation: frequency and associated factors among undergraduate women in Brazil. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0783-9.

Samosir, O. B., Kiting, A. S. and Aninditya, F. (2019) ‘Determinants of contraceptive discontinuation in Indonesia: further analysis of the 2017 Demographic and Health Survey.’DHS Working Papers, (159), ix-pp. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP159/WP159.pdf.

MoHCDGEC, et al. Tanzania demographic and health survey 2015/16 final report. In: Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS); 2016. p. 2015–6.

Keogh, S. C. et al. (2011) ‘Dynamics of postpartum contraceptive use, and their relationship to antenatal intentions, in northern Tanzania’.

Elewonibi B, Sato R, Manongi R, Msuya S, Shah I, Canning D. The distance-quality trade-off in women’s choice of family planning provider in North Eastern Tanzania. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(2):e002149. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002149.

Eliason, et al. Postpartum fertility behaviours and contraceptive use among women in rural Ghana. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-018-0066-9.

Puri M, Henderson JT, Harper CC, Blum M, Joshi D, Rocca CH. Contraceptive discontinuation and pregnancy postabortion in Nepal: a longitudinal cohort study. Contraception. 2015;91(4):301–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.011 Elsevier Inc.

Bradley SEK, Schwandt HM, Khan S. Levels, Trends, and Reasons for Contraceptive Discontinuation. DHS Analytical Studies No. 20. Calverton: ICF Macro; 2009.

Cohen R, Sheeder J, Arango N, Teal SB, Tocce K. Twelve-month contraceptive continuation and repeat pregnancy among young mothers choosing postdelivery contraceptive implants or postplacental intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2016;93(2):178–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.001 Elsevier Inc.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants for their valuable participation in this study. We also thank the Arusha Regional Medical Officer, District Medical Officers and other administrative staff in Arusha city and Meru district; for their cooperation and support during the study period. Furthermore, we would like to thank the research assistants for their positive participation and involvement in this study.

Funding

There was no fund allocated for this project. This was part of the student project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SEM, BE and IS designed the study. All authors were involved in data collection. RS and MJM conducted data analysis. MJM, RS and BE drafted the manuscript. MJM RS RM CA BE SEM and IS contributed to the final draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and gave their final approval to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College Research and Ethics committee as well as National Institute for Medical Research. The study was approved by Harvard Institutional Review Board. The permission to conduct the study was also sought from TAMISEMI/ regional and district level. All issues related to confidentiality and privacy were adhered. Participants’ confidentiality were maintained throughout the study period by using identification numbers instead of participant names. Written consent were obtained from individual participants before recruitment for a study.

Consent for publication

The permission to publish the data was obtained from the study participants after being fully informed about the objectives of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahande, M.J., Sato, R., Amour, C. et al. Predictors of contraceptive discontinuation among postpartum women in Arusha region, Tanzania. Contracept Reprod Med 6, 15 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-021-00157-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-021-00157-6