Abstract

Contamination of biomedical devices in a biological medium, biofouling, is a major cause of infection and is entirely avoidable. This mini-review will coherently present the broad range of antifouling strategies, germicidal, preventive and cleaning using one or more of biological, chemical and physical techniques. These techniques will be discussed from the point of view of their ability to inhibit protein adsorption, usually the first step that eventually leads to fouling. Many of these approaches draw their inspiration from nature, such as emulating the nitric oxide production in endothelium, use of peptoids that mimic protein repellant peptides, zwitterionic functionalities found in membrane structures, and catechol functionalities used by mussel to immobilize poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). More intriguing are the physical modifications, creation of micropatterns on the surface to control the hydration layer, making them either superhydrophobic or superhydrophilic. This has led to technologies that emulate the texture of shark skin, and the superhyprophobicity of self-cleaning textures found in lotus leaves. The mechanism of antifouling in each of these methods is described, and implementation of these ideas is illustrated with examples in a way that could be adapted to prevent infection in medical devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Biofouling is the contamination of surfaces by microbes that include bacteria (prokaryotes), fungi and viruses. In medical applications, biofouling occurs on surgical equipment, protective apparel, packaging, guide wires, sensors, prosthetic devices, and medical implants, and most familiarly on catheters, drug delivery devices and contact lenses. Microbial contamination, and the subsequent risk of infection, biosensor failure and implant rejection, is a major driver in developing efficient antifouling strategies [1]. According to a recent study initiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 26 % of the health-care related infections are caused by these device-associated infections in U.S. acute care hospitals alone in 2011 [2]. Prevention of morbidity and mortality associated with biofilm-mediated infections calls for the replacement of contaminated devices, as well as treatment with antibiotics, which sometimes may be ineffective [3].

Since biofouling is mediated by proteins, inhibition of protein adsorption prevents the cause of infection at the source. The layer of adsorbed protein on surfaces serves as a platform for cell attachment, and subsequent bacterial colonization that leads to the formation of bacterial films [4]. Protein fouling is a major challenge in the development of numerous blood-contacting biomedical devices caused by the nonspecific adhesion of biological components including proteins to the device surface. These pro-inflammatory processes result in thrombus formation, which leads to platelet formation, and ultimately to device failures and fatal complications. There are many excellent reviews [5–7] on antifouling strategies for a wide variety of applications, marine, industrial (e.g., reverse osmosis membranes), and biomedical applications [8–12]. We distinguish our review from these by focusing on biomedical devices and discuss a broad range of possible methods, biological, chemical and physical, in sufficient detail.

Strategies for making antifouling biomedical surfaces

There are three strategies: First is the use of biocides, antibacterials that kill bacteria or antimicrobial that kill bacteria and other microorganisms. Second is to repel the proteins, and subsequently cells, and thus prevent biofouling. Third is to create surfaces that self-clean so that the organisms do not remain attached. Nature appears to have developed a combination of these approaches.

The methods that are currently used or in conceptual stages create antifouling surfaces on blood-contacting biomedical devices either chemically modify the surface composition or physically alter the surface topography. These methods alter the hydration layer at the surface and thereby inhibit the adsorption of proteins. Exceptions are the nitric oxide (NO)-based technique that kills the cells and peptide/peptoid-based methods that attempt to prevent cells for adhering to the surface. In this review, we will discuss the key strategies for inhibiting protein adsorption on biomedical devices and emphasize the principle, mechanisms and illustrate them with a few applications. In the following sections we will review two chemical techniques, one based on impregnating the surface with biological molecules and the other that incorporates biologically active synthetic components onto the device’s surface, and two physical techniques in which antifouling is achieved by micropatterning. These are listed in Table 1.

Use of biological molecules

Use of biological molecules for antifouling applications are attractive as these are naturally occurring biomolecules or entities that are inherently less toxic, more efficient, and have greater specificity than many synthetic compounds [9]. Three of the most promising molecules are nitric-oxide releasing materials, peptides and peptoids.

Nitric oxide-releasing materials

Nitric oxide (NO) is a bactericidal agent. Unlike other germicidal release coatings such as silver nanoparticles and antibiotics, NO is naturally produced. It is an endothelium-derived relaxing factor that is responsible for regulating the natural homeostasis [13]. NO can disperse biofilm through a number of mechanisms including the production of oxidative or nitrosative stress-inducing moieties within the biofilm structure, bacteriophage induction and cell lysis [14]. For this reason, endothelium is one of the most thromboresisitive materials. Consequently, materials that can release NO at a steady-state equivalent to that released by the natural endothelium (0.5 × 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1) [15], can be a suitable material for making biomedical devices with enhanced antifouling capabilities [16, 17]. Liu et al. recently demonstrated that the presence of NO significantly reduces the formation of Shewanella woodyi (S. woodyi) biofilm by simultaneously down-regulating the cyclase activity and up-regulating the phosphodiesterase activity of the diguanylate cyclase gene (SwDGC) (Fig. 1) [18]. In vivo SwDGC and SwH-NOX form a complex. In the absence of NO, SwH-NOX is associated with SwDGC and maintains its basal phosphodiesterase activity while enhancing diguanylate cyclase activity. Upon detection of NO, SwH-NOX downregulates diguanylate cyclase activity and activates phosphodiesterase activity. Therefore, NO reduces the c-di-GMP concentration in S. woodyi, leading to a reduction in the extent of biofilm formation. This hypothesis suggests that NO can reduce the c-di-GMP concentration in S. woodyi, leading to a reduction in the extent of biofilm formation.

A model for NO regulation of c-di-GMP synthesis in S. woodyi suggested by Liu et al. Reproduced with permission from ref. [18] © American Chemical Society

Initial studies using the NO-donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) have shown that use of sub lethal concentrations (25 to 500 nM) of the NO-donor resulted in a significant dispersal of bacterial biofilms (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [14]. In another study, researchers demonstrated that NO released from the donor PROLI/NO (1-[2-(carboxylato)-pyrrolidin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate) resulted in nearly 66 % reduction in proteins and nearly 50 % reduction in the biofilm surface coverage compared to the untreated control [19]. Similarly, using another NO-donor, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicilamine (SNAP), Brisbois et al. successfully demonstrated a 90 % reduction in bacterial adhesion and infection by NO-releasing materials in a 7 days animal model [20].

From a clinical perspective, NO-releasing products can also provide potential advantages in controlling biofilm-related infections by releasing biofilm-specific enzymes such as β–lactamase. In one such attempt, Barraud et al. used cephalosporin-3′-diazeniumdiolate as the NO-donor pro-drug [21]. The β–lactam analog, cephalosporin, functioned as a protecting barrier for the NO-donor and the site specific NO-release was achieved upon specific activation by the bacterial enzyme β–lactamase (Fig. 2). This innovative pro-drug was found to be very effective in dispersing biofilms of various pathogenic species suggesting this as a potential precursor for developing anti-biofilm therapeutics.

Mechanism of β-lactamase-triggered NO release and biofilm dispersion by cephalosporin-3′-diazeniumdiolate. Adapted from ref. [21]

Although NO can be an effective molecule for the prevention of biofilm formation and biofilm-related infections, its use in many biomedical applications remains a challenge because of high reactivity and short half-life, its requirement for proper storage and delivery. Covalent incorporation of a suitable NO-donor during the synthesis or impregnating it into a suitable matrix during the processing are some of the approaches reported to date for modulating the NO-release towards biomedical applications [22–25]. One other limitation with the NO approach is that in certain instances NO was found to have no influence, and even stimulate biofilm formation in certain types of bacterial colonies [26–28]. Consequently, NO may be used selectively for controlling the biofilm formation in certain types of bacteria. Since there is a large range of biofilm responses, detailed research is required to establish the generalized use of NO over a variety of non-fouling applications.

Peptide and peptoid modified surfaces

Many peptide-based materials are used as antifouling agents because of their exceptional resistance to proteins including bovine serum albumin, fibrinogen, fibronectin, lysozyme, and streptavidin [29, 30]. Naturally occurring biomolecule such as amino acids, peptides, and polysaccharides are also commonly used in the development of innovative antifouling materials. Many of these biomolecules are believed to undergo structural reformations under physiological conditions to prevent biofouling [31]. Peptoids are non-natural biomimetic polymers. Unlike poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and zwitterions that will be discussed shortly, the surface structure and antifouling ability of the peptide- and peptoid-based materials can be tuned [31, 32]. Many known antifouling functionalities can be incorporated using a single backbone chemistry, and done so at precisely known locations, because of the sequence specificity of polypeptoids. A library of such sequence-specific materials can be designed for optimum performance.

In one example, a biomimetic antifouling material was prepared by Perrino et al. [33] by grafting dextran side chain to a poly(L-lysine) (PLL) backbone. The PLL-graft-dextran copolymer was found to have excellent antifouling properties to prevent nonspecific adsorption of proteins in a variety of architectures similar to a PEG-grafted analog. A similar biomolecule-based approach is to incorporate proteases onto the material surfaces. In one such attempt, Kim et al. [34] prepared protein resistant films by immobilizing hydrolytic enzymes pronase and α-chymotrypsin by sol–gel entrapment followed by covalent attachment to a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) matrix.

In another example, peptidomimetic synthetic approaches have been used to produce novel sequence-defined synthetic polymers that mimic the overall topology and biological activities of various natural peptides [35]. Using this method, polypeptoids (N-substituted glycines) have been synthesized for use as surface coatings with robust and long-term antifouling properties in biological environments. Figure 3 illustrates one example of this approach in which Statz et al. prepared a chimeric peptidomimetic peptide-peptoid based material (PMP1) using an N-substituted glycine and a short functional peptide [36]. The short functional peptide domain provided robust adsorption to various surfaces, while the peptoid oligomer provides resistance to protein and cell fouling. The material exhibited a significant reduction of serum protein adsorption in vitro and showed exceptional resistance to mammalian cell attachment for over five months. Poly(β-peptoids) (poly(N-alkyl-β-alanine)s) [37] also exhibited excellent resistant to nonspecific protein adsorption due to the strong hydrogen-accepting ability of these polymers under physiological conditions.

Structural details of a peptidomimetic polymer (PMP1). Reproduced with permission from ref. [36] © American Chemical Society

Chemical modification of surfaces

Unlike the approaches discussed in a previous section, need exists for non-specific protein repulsion. This can be achieved by incorporating hydrophilic polymers such as PEG, amphiphilic fluoropolymers, zwitterionic polymers [6]. Chen et al. have summarized these polymers under two major classes, polyhydrophilic and poly zwitterionic [38]. While hydrophilic polymers resist protein adsorption by forming a hydration layer, hydrophobic surfaces prevent fouling by being able to readily release the adsorbed proteins and cells. All these polymers can be applied onto a variety of surfaces by one of many physical techniques such as spin-coating and dip-coating, or chemical methods such as covalent grafting. We will discuss the application of some of these polymers to biomedical devices.

Hydrophilic polymers

Surface modification with PEG is widely used in preventing biofouling on medical devices [39]. Each ethylene glycol repeating unit in the PEG backbone can strongly bind to one water molecule, bridging the ether oxygen along the 72 helical PEG chain [40–42]. This unique interaction between the water and the PEG chain results in the formation of a highly hydrated layer and ultimately leads to a steric hindrance to the approaching protein molecules [38]. When a protein molecule approaches a hydration layer barrier, the resulting compression of the layer can decrease the conformational entropy of the polymer chains that ultimately lead to the repulsion of the approaching proteins. Such a hydration layer does not occur in polyoxymethylene even with its higher O/C ratio. High mobility and large exclusion volume of the PEG chains also contribute towards the overall antifouling characteristics of the polymer.

Despite the attractiveness of PEG as an antifouling agent, low surface densities [43, 44] and susceptibility to oxidative damages [45] limit their antifouling capabilities overlong-term applications. Additionally, it has been shown that reactive oxygen species, produced by PEG might modulate the cell response [46]. For these reasons, alternate hydrophilic polymers such as polyglycerols [47], polyoxazolines [48], polyamides [49], and naturally occurring polysaccharides [17] have been evaluated for antifouling applications.

Immobilization of PEG

A surface can be functionalized with PEG by using either adsorption of presynthesized PEG onto the surface (graft-to strategy), or by growing the polymer in-situ via surface adsorbed initiation group (graft-from strategy) [50]. Both of these techniques immobilize PEG on surfaces to confer them with protein and cell resistance. However, anchoring PEG by using functional groups on the surface requires extensive chemical modification of the surface, especially to make them less susceptible to thermal and hydrolytic degradation, and is therefore limited by the surface chemistry.

Following nature’s cues, PEG can be robustly anchored onto a variety of surfaces using a mussel-mimicking linker, adhesive L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), a catechol functionality [51]. DOPA, DOPA peptides, or a catechol-mimic molecule can be covalently attached to the PEG terminal hydroxyl groups or to side chains. Alternatively, DOPA or a catechol-based monomer can be directly incorporated into the polymer backbone during polymerization. The catechol segment imparts the cohesive and adhesive characteristics, while PEG contributes to the antifouling characteristics [52].

PEG surface immobilization can be done through the formation of either polymer loops or brushes. In both these instances, PEGs with end-tethered or pendent functionalized with DOPA derivatives were used to target surface immobilization through stable anchoring. In a representative approach, Li et al. reported the successful evaluation of a catechol-functionalized PEG-based ABA triblock polymer loops for antifouling applications. It was shown that the polymer loops prepared from an ABA triblock copolymer, poly[(N,N-dimethylacrylamide)15-co-(N-3,4-dihydroxyphenethyl acrylamide)2]-b-poly(ethylene glycol)90-b-poly[(N,N-dimethylacrylamide)15-co-(N-3,4-dihydroxyphenethyl acrylamide)2] (PDN-PEG-PDN) had better antifouling properties than the polymer brushes prepared from its diblock analog, poly[(N,N-dimethylacrylamide)15-co-(N-3,4-dihydroxyphenethyl acrylamide)2]-b-poly(ethylene glycol)45 (PDN-PEG) (Fig. 4) [53]. The polymer loops showed a better adaptation towards the external compression exerted by the approaching proteins and reduced the protein penetration than the polymer brushes prepared from the diblock polymers with similar graft density. Therefore, such polymer loops with catechol-functionalities provide strong anchoring to surfaces. Because of the extremely low friction coefficient and enhanced inhibition of cell adhesion and proliferation, they provide a superior option for making ocular lenses and articular implants [54].

a Chemical structure of the triblock copolymer PDN-PEG-PDN and the diblock copolymer PDN-PEG. b Schematics of the preparation of surfaces bearing polymer brushes and polymer loops using drop coating method. Reproduced with permission from ref. [53] © Royal Society of Chemistry

Zwitterionic polymers

Zwitterionic materials are amphoteric materials with both positive and negative charges. Because of the strong dipoles of the zwitterions and electrostatic itneractions, they have a stongly bound hydration layer that leads to “superhydrophilicity” and high protein resistivity [55]. Consequently, the extent of nonfouling characteristics exhibited by this group of materials is greater than that observed with hydrophilic/hydrophobic materials. Zwitterionic phospholipids such as phosphorylcholine constitute the outer surface of the nonthrombogenic erythrocyte cell membranes [56, 57]. Inspired by the antifouling properties of these naturally occurring membrane molecules, researchers have explored the potential utility of zwitterionic polymeric materials such as polybetaines or its structural analogs in a variety of biomedical applications, including nonthrombogenic surfaces [58].

An early example of bio-membrane mimicry is the preparation of phosphobetaine (PB)-based antifouling surfaces by incorporating the structural analogs of the naturally occurring lipid dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC), such as diacetylenic phosphatidylcholine (DAPC) and methacryloyloxyalkyl phosphorylcholines (MAPC) [59–62]. Because of the characteristic ability of the phosphobetaines to retain a large amount of water with the zwitterionic head groups while retaining protein repulsion, PB-modified hydrogels are finding their importance in contact lens applications for improving the wettability and surface properties [63].

Other polybetaines, such as carboxybetaines (CB) and sulfobetaines (SB) are also been extensively evaluated for various nonfouling biomedical applications. Among these, CB is attractive because of its unique capability for immobilizing ligands such as proteins and antibodies, onto the carboxyl groups [64, 65]. Cheng et al. used a cationic precursor of poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate) (polyCBMA) to produce a switchable polymer surface coating with self-sterilizing and nonfouling capabilities [66, 67]. The cationic precursor of polyCBMA killed more than 99.9 % of Escherichia coli K 12 in 1 h and upon hydrolysis switched to a zwitterionic nonfouling surface with the release of more than 98 % of the dead bacterial cells and prevented any further protein attachment and biofilm formation.

Like many carboxybetaines, densely packed poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (polySBMA)-grafted surfaces have also been found to be completely resistant to the adsorption of a number of plasma proteins including human serum albumin, gamma globulin, fibrinogen, and lysozyme, even at low ionic concentrations [68–70]. PolyCBMA is also an interesting polymer for making blood-compatible surfaces, because of its structural comparability with the naturally occurring glycine betaine. Furthermore, the surface carboxyl groups polyCBMA provide a suitable platform for covalent immobilization of bioactive species such as monoclonal mouse antibody (mAb, anti-hCG) for specifically binding to human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) while retaining the nonspecific protein repellency [71]. This dual functional behavior of polyCBMA makes it useful for the design of antifouling surfaces for biosensors and diagnostic applications.

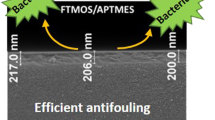

Hydrophobic polymers

Hydrophobic coatings have been developed in textile industry to prevent staining [72]. These coating are effective as fouling release agents. In one study, Privett et al. reported the development of a superhydrophobic xerogel coating synthesized from a mixture of nanostructured fluorinated silica colloids, fluoroalkoxysilane, and a backbone silane [73]. The researchers showed a significant reduction in the adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa.) on this fluorinated surface compared to their control samples. In another example, Li et al. [74] used a hydrophobic liquid-infused porous poly(butyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) surface (slippery BMA-EDMA) for reducing the adhesion of P. aeruginosa. Only ~1.8 % of the slippery surface was covered by the environmental P. aeruginosa PA49 strain whereas the uncoated glass controls exhibited coverage of ~55 % under the same conditions. However, mainly due to the toxicity concerns, the hydrophobic polymers are not studied as extensively as their hydrophilic analogs.

Recently, Xue et al. reported the development of superhydrophobic antifouling poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) fabrics by chemical etching followed by grafting of fluorinated methacrylate polymers via surface-initiated atom radical polymerization (SI-ATRP) [72]. The hydrophobicity of the surfaces were controlled by tuning the polymerization time and a contact angle of nearly 160 ° was reported by the researchers after 8 h with excellent antifouling properties. Since PET is extensively used in a variety of biomedical applications, this innovative approach can be adapted to improve the antifouling properties of many currently available biomedical devices.

Micropatterning of surfaces

Influence of surface texture

It has been known for more than 100 years that cell response is influenced by surface topology [75]. Investigations over the past 50 years have demonstrated that surface topography in the μm length scale affects the cell adhesion [76–81]. Many of these investigations were carried out in the context to cell survival and promotion of cell growth. Recent work has shown that such surface topography can be used reduce biofilm formation [82]. The discovery that such topography is in fact used by marine species to prevent biofouling has inspired the development of strategies for developing similar surfaces on biomedical devices [10, 83]. Topographical features suitable for controlling cell adhesion are traditionally produced by photolithography [82]. Alternative approaches include demixing [84–86], dewetting [87], solvent evaporation [84], and laser ablation [88]. These and other techniques can produce micro-topographies found on leaves on many plants, most well known being lotus, and dermal denticles on skins of marine organisms such as shark, whales, bottlenose dolphin mussels, snail shells, and edible crab.

The mechanisms by which the naturally occurring micro-topographic features prevent biofilm formation are still not clear. There are at least four mechanisms that contribute to the antifouling properties of the surface. In one mechanism, the lotus effect, superhydrophobity of the surface causes water to bead up on the surface, and pick up the contaminants as it rolls off the surface, and thus prevent attachment of any cells onto the surface [11, 89]. In the second mechanism, the topography is such that it prevents cellular attachment [90, 91]. In the third, the drag and the efficient flow of water, sloughs off the organism of the surface [10]. According to the fourth mechanism, marine animals secrete substances contribute to the antifouling properties of these surfaces [83, 92]. Irrespective of the mechanisms, these bioinspired structures, since they do not alter the chemical composition or add extraneous chemical into the mix, have found potential use in applications such as catheters [93]. We will discuss two bioinspired micropatterns that highlight this class of structures.

Superhydrophobic self-cleaning surfaces

Water drops that fall upon the surface of leaves of certain plants such as that of lotus move freely on the surface, collect contaminants as they roll of the surface [94]. Such self-cleaning capabilities that results from the super-hydrophobicity has inspired the development of a similar architecture that can be imprinted on biomedical devices. This lotus effect arises from two levels of structure seen under electron microscope [93, 95, 96]. As seen in Fig. 5a, there are micro-scale mound like structures that are decorated with nano-scale hair-like structures. The air trapped in the cavities between the convex shaped cones minimize wetting making the surface hydrophobic. The hair like structure are hydrophobic hydrocarbon tubules. A combination of the micro-cones and waxy nano-structures make the surface superhydrophobic with contact angle between 90° and 150°. More importantly, the contact angles have very small hysteresis that allows the droplets to roll off the leaf and thus making the structure self-cleaning. Such surfaces can be produced by lithographic techniques [12, 89] as well as by self-assembly techniques [88].

It should be noted, that the 2nd level of wax-like hairy is important for the superhydrophobicity of the surface. There are cone-like structures that lack the hair features present on the cones of lotus leaf. As a consequence, a droplet of water spreads on these leaves. Such structures are present on the leaves of plants such as Calathea Zebra [95]. The structure shown in Fig. 5b mimics these hair-less cones, and was obtained laser ablation of a polyester film [88]. These structures are formed by self-assembly, and can thus be formed on any complex surface found on medical devices.

Topography driven antifouling

One of the widely successful surface patterns for antifouling are inspired by shark skin is a combination of self-cleaning and low adhesion/drag surfaces (Fig. 6a). In general, the shape of the groves contribute to the low-drag and the self-cleaning properties of the shark skin. Analysis of the microtopographies present various marine species have suggested several key surface parameters that influence antifouling: low fractal dimension, high skewness of roughness and waviness, higher values of anisotropy, lower values mean roughness leading to improved antifouling characteristics [10, 97, 98]. Carman et al. [99] fabricated engineered multifeature topography in a polydimethylsiloxane elastomer to replicate the skin of fast moving sharks (Sharklet AF™) (Fig. 6b). Nearly 85 % reduction in the settlement of Ulva linza zoospores were achieved with the complex Sharklet AF™ topographies which consist of 2 μm wide engineered channels.

Sharklet technologies mimicking the micropatterns on Shark skin. a Skin of a Bull Shark © AMNH/R. Rudolph. Reproduced with the permission from the American Museum of Natural History (enlarged from the original). b Topography mimicked in the Sharklet™ surface technology. Reproduced with the permission of Prof. Brennan, Biomedical Engineering, University of Florida

Although Micropatterned surfaces by themselves have been shown to reduce the transfer of bacterial contamination [100], there are other reports that suggest additional chemical modification may be necessary to achieve the desired level of antifouling [83]. For instance, mucous found on the shark skin also provides lubricating and antifouling benefits [92]. In another study, decoupling the surface chemistry from the topography lead to fouling of such surface during 3 to 6 weeks of immersion [101]. Such studies show that topographical features and surface properties can play a major role in designing antifouling surfaces for innovative biomedical surfaces [100].

The surface patterning involves surface modification via nanoparticles, photolithography, mesoporous polymers, or surface etching, sometimes in conjunction with additional chemical modifications to reduce surface energy. These often require harsh synthetic conditions complex fabrication techniques [89, 102, 103] thus limiting the substrate type and geometry that may be coated.

Conclusions

Antifouling can be achieved by mimicking the strategies developed by nature instead of using synthetic antimicrobials and antibiotics. We have presented several strategies that can be adopted on biomedical devices and a comparative summary of various methods is presented in Table 1. Nitric oxide (NO) releasing agents are based on processed used by endothelium. Peptides and peptoids use specific protein repulsion approaches. There are widely successful approaches based on hydration layer that uses hydrophilic polymers such PEG and zwitterions. Several micropatterning approaches that mimic the surfaces of plant leaves and skins of marine animals are also discussed. These methods suggest the many ways in which the formation of biofilms on the material surface can be prevented in various biomedical devices particularly for blood-contacting biomedical applications.

Abbreviations

BMA-EDMA, poly(butyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate); CB, carboxybetaine; c-di-GMP, cyclic diguanylate; DAPC, diacetylenic phosphatidylcholine; DOPA, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine; DPPC, dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MAPC, methacryloyloxyalkyl phosphorylcholine; NO, Nitric oxide; P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PB, phosphobetaine; PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane; PDN-PEG, poly[(N,N-dimethylacrylamide)15-co-(N-3,4-dihydroxyphenethyl acrylamide)2]-b-poly(ethylene glycol)45; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); PET, poly(ethylene terephthalate); PLL, poly(L-lysine); PMP1, a peptidomimetic peptide-peptoid based material; polyCBMA, poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate); polySBMA, poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate); PROLI/NO, 1-[2-(carboxylato)-pyrrolidin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate; S. woodyi, Shewanella woodyi; SB, sulfobetaine; SI-ATRP, surface-initiated atom radical polymerization; SNAP, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicilamine; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; SwDGC, diguanylate cyclase gene of S. woodyi; SwH-NOX, S. woodyi with heme-nitric oxide/oxygen binding

References

Chan J, Wong S. Biofouling: Types, Impact, and Anti-fouling. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2010.

Magill SS et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care–associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198–208.

Lehman SM, Donlan RM. Bacteriophage-mediated control of a two-species biofilm formed by microorganisms causing catheter-associated urinary tract infections in an in vitro urinary catheter model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):1127–37.

Costerton JW, Montanaro L, Arciola CR. Biofilm in implant infections: Its production and regulation. Int J Artif Organs. 2005;28(11):1062.

Banerjee I, Pangule RC, Kane RS. Antifouling coatings: recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Adv Mater. 2011;23(6):690–718.

Krishnan S, Weinman CJ, Ober CK. Advances in polymers for anti-biofouling surfaces. J Mater Chem. 2008;18(29):3405–13.

Zhou F. Antifouling Surfaces and Materials. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

Xiong Y, Liu Y. Biological control of microbial attachment: a promising alternative for mitigating membrane biofouling. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86(3):825–37.

Malaeb L, et al. Do biological-based strategies hold promise to biofouling control in MBRs? Water Res. 2013;47(15):5447–63.

Salta M, et al. Designing biomimetic antifouling surfaces. Philos T Roy Soc A. 2010;368(1929):4729–54.

Bixler GD, Bhushan B. Biofouling: lessons from nature. Philos T Roy Soc A. 2012;370(1967):2381–417.

Bixler GD, et al. Anti-fouling properties of microstructured surfaces bio-inspired by rice leaves and butterfly wings. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;419:114–33.

Ignarro LJ, et al. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84(24):9265–9.

Barraud N, et al. Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm dispersal of pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(21):7344–53.

Damodaran VB, et al. S-Nitrosated biodegradable polymers for biomedical applications: synthesis, characterization and impact of thiol structure on the physicochemical properties. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(13):5990–6001.

Damodaran VB, Reynolds MM. Nitric oxide-releasing biomedical materials. In: Mishra MK, editor. Encyclopedia of biomedical polymers and polymeric biomaterials. NY: Taylor & Francis; 2015. doi:10.1081/E-EBPP-120049951.

Damodaran VB, et al. Antithrombogenic properties of a nitric oxide-releasing dextran derivative: evaluation of platelet activation and whole blood clotting kinetics. RSC Advances. 2013;3(46):24406–14.

Liu N, et al. Nitric oxide regulation of cyclic di-GMP synthesis and hydrolysis in Shewanella woodyi. Biochemistry. 2012;51(10):2087–99.

Barnes RJ, et al. Nitric oxide treatment for the control of reverse osmosis membrane biofouling. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(7):2515–24.

Brisbois EJ, et al. Reduction in thrombosis and bacterial adhesion with 7 day implantation of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-doped Elast-eon E2As catheters in sheep. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3(8):1639–45.

Barraud N, et al. Cephalosporin-3′-diazeniumdiolates: targeted NO-donor prodrugs for dispersing bacterial biofilms. Angewandte Chemie. 2012;124(36):9191–4.

Damodaran VB, et al. Enzymatically degradable nitric oxide releasing S-nitrosated dextran thiomers for biomedical applications. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(43):23038–48.

Koh A, et al. Nitric oxide-releasing silica nanoparticle-doped polyurethane electrospun fibers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(16):7956–64.

Colletta A, et al. S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) impregnated silicone foley catheters: a potential biomaterial/device to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2015;1(6):416–24.

Joslin JM, Damodaran VB, Reynolds MM. Selective nitrosation of modified dextran polymers. RSC Advances. 2013;3(35):15035–43.

Zaitseva J, et al. Effect of nitrofurans and NO generators on biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and Burkholderia cenocepacia 370. Res Microbiol. 2009;160(5):353–7.

Schmidt I, et al. Physiologic and proteomic evidence for a role of nitric oxide in biofilm formation by nitrosomonas europaea and other ammonia oxidizers. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(9):2781–8.

Arruebarrena Di Palma A, et al. Denitrification-derived nitric oxide modulates biofilm formation in Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;338(1):77–85.

Chelmowski R, et al. Peptide-based SAMs that resist the adsorption of proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(45):14952–3.

Chen S, Cao Z, Jiang S. Ultra-low fouling peptide surfaces derived from natural amino acids. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5892–6.

Leng C, et al. Surface structure and hydration of sequence-specific amphiphilic polypeptoids for antifouling/fouling release applications. Langmuir. 2015;31(34):9306–11.

van Zoelen W, et al. Sequence of hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues in amphiphilic polymer coatings affects surface structure and marine antifouling/fouling release properties. ACS Macro Letters. 2014;3(4):364–8.

Perrino C, et al. A biomimetic alternative to poly(ethylene glycol) as an antifouling coating: resistance to nonspecific protein adsorption of poly(l-lysine)-graft-dextran. Langmuir. 2008;24(16):8850–6.

Kim YD, Dordick JS, Clark DS. Siloxane-based biocatalytic films and paints for use as reactive coatings. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;72(4):475–82.

Mason JM. Design and development of peptides and peptide mimetics as antagonists for therapeutic intervention. Future Med Chem. 2010;2(12):1813–22.

Statz AR, et al. New peptidomimetic polymers for antifouling surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(22):7972–3.

Lin S, et al. Antifouling poly(β-peptoid)s. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(7):2573–82.

Chen S, et al. Surface hydration: principles and applications toward low-fouling/nonfouling biomaterials. Polymer. 2010;51(23):5283–93.

Harris JM. Poly (ethylene glycol) chemistry: biotechnical and biomedical applications. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 1992.

Lüsse S, Arnold K. The interaction of poly(ethylene glycol) with water studied by 1H and 2H NMR relaxation time measurements. Macromolecules. 1996;29(12):4251–7.

Oesterhelt F, Rief M, Gaub H. Single molecule force spectroscopy by AFM indicates helical structure of poly (ethylene-glycol) in water. New J Phys. 1999;1(1):6.

Aray Y, et al. Electrostatics for exploring the nature of the hydrogen bonding in polyethylene oxide hydration. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108(7):2418–24.

Kingshott P, et al. Covalent attachment of poly(ethylene glycol) to surfaces, critical for reducing bacterial adhesion. Langmuir. 2003;19(17):6912–21.

Damodaran VB, Fee CJ, Popat KC. Prediction of protein interaction behaviour with PEG-grafted matrices using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl Surf Sci. 2010;256(16):4894–901.

Ostuni E, et al. A survey of structure–property relationships of surfaces that resist the adsorption of protein. Langmuir. 2001;17(18):5605–20.

Sung H-J, et al. Poly (ethylene glycol) as a sensitive regulator of cell survival fate on polymeric biomaterials: the interplay of cell adhesion and pro-oxidant signaling mechanisms. Soft Matter. 2010;6(20):5196–205.

Weber T, et al. Direct grafting of anti-fouling polyglycerol layers to steel and other technically relevant materials. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;111:360–6.

Konradi R, Acikgoz C, Textor M. Polyoxazolines for nonfouling surface coatings — a direct comparison to the gold standard PEG. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2012;33(19):1663–76.

Lopez AI, et al. Biofunctionalization of silicone polymers using poly(amidoamine) dendrimers and a mannose derivative for prolonged interference against pathogen colonization. Biomaterials. 2011;32(19):4336–46.

Gölander C-G, et al. Properties of immobilized PEG films and the interaction with proteins, in Poly (ethylene glycol) Chemistry. Berlin: Springer; 1992. p. 221–45.

Dalsin JL, et al. Mussel adhesive protein mimetic polymers for the preparation of nonfouling surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(14):4253–8.

Lee BP, et al. Mussel-inspired adhesives and coatings. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2011;41(1):99–132.

Li L, et al. Mussel-inspired antifouling coatings bearing polymer loops. Chem Commun. 2015;51(87):15780–3.

Kang T, et al. Mussel-inspired anchoring of polymer loops that provide superior surface lubrication and antifouling properties. ACS Nano. 2016;10(1):930–7.

Damodaran VB, et al. Zwitterionic polymeric materials. In: Mishra MK, editor. Encyclopedia of biomedical polymers and polymeric biomaterials. NY: Taylor & Francis; 2015. doi:10.1081/E-EBPP-120050037.

Zwaal RFA, Schroit AJ. Pathophysiologic implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood. 1997;89(4):1121–32.

Zwaal RFA, Comfurius P, Van Deenen LLM. Membrane asymmetry and blood coagulation. Nature. 1977;268(5618):358–60.

Lewis AL. Phosphorylcholine-based polymers and their use in the prevention of biofouling. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2000;18(3–4):261–75.

Hall B, et al. Biomembranes as models for polymer surfaces: V. Thrombelastographic studies of polymeric lipids and polyesters. Biomaterials. 1989;10(4):219–24.

Hayward JA, et al. Biomembpanes as models for polymer surfaces. Biomaterials. 1986;7(2):126–31.

Ishihara K, et al. Modification of polysulfone with phospholipid polymer for improvement of the blood compatibility. Part 1. Surface characterization. Biomaterials. 1999;20(17):1545–51.

Kojima M, et al. Interaction between phospholipids and biocompatible polymers containing a phosphorylcholine moiety. Biomaterials. 1991;12(2):121–4.

Willis SL, et al. A novel phosphorylcholine-coated contact lens for extended wear use. Biomaterials. 2001;22(24):3261–72.

Yang W, et al. Pursuing “zero” protein adsorption of poly(carboxybetaine) from undiluted blood serum and plasma. Langmuir. 2009;25(19):11911–6.

Cheng G, et al. Zwitterionic carboxybetaine polymer surfaces and their resistance to long-term biofilm formation. Biomaterials. 2009;30(28):5234–40.

Cheng G, et al. Integrated antimicrobial and nonfouling hydrogels to inhibit the growth of planktonic bacterial cells and keep the surface clean. Langmuir. 2010;26(13):10425–8.

Cheng G, et al. A switchable biocompatible polymer surface with self-sterilizing and nonfouling capabilities. Angewandte Chemie. 2008;120(46):8963–6.

Chang Y, et al. Hemocompatible mixed-charge copolymer brushes of pseudozwitterionic surfaces resistant to nonspecific plasma protein fouling. Langmuir. 2010;26(5):3522–30.

Yang W, et al. Film thickness dependence of protein adsorption from blood serum and plasma onto poly(sulfobetaine)-grafted surfaces. Langmuir. 2008;24(17):9211–4.

Li G, et al. Ultra low fouling zwitterionic polymers with a biomimetic adhesive group. Biomaterials. 2008;29(35):4592–7.

Zhang Z, Chen S, Jiang S. Dual-functional biomimetic materials: nonfouling poly(carboxybetaine) with active functional groups for protein immobilization. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(12):3311–5.

Xue C-H, et al. Fabrication of robust and antifouling superhydrophobic surfaces via surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(15):8251–9.

Privett BJ, et al. Antibacterial fluorinated silica colloid superhydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir. 2011;27(15):9597–601.

Li J, et al. Hydrophobic liquid-infused porous polymer surfaces for antibacterial applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(14):6704–11.

Harrison RG. On the stereotropism of embryonic cells. Science. 1911;43(870):279–81.

Recum AFV, et al. Surface roughness, porosity, and texture as modifiers of cellular adhesion. Tissue Eng. 1996;2(4):241–53.

Curtis A, Varde M. Control of cell behavior: topological factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1964;33(1):15–26.

Korman N, Sudilovsky O, Gibbons D. The effect of humoral components on the cellular response to textured and nontextured PTFE. J Biomed Mater Res. 1984;18(2):225–41.

Curtis A, Wilkinson C. Topographical control of cells. Biomaterials. 1997;18(24):1573–83.

Chen CS, et al. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276(5317):1425–8.

Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Engineering substrate topography at the micro‐and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48(30):5406–15.

Xu L-C, Siedlecki CA. Submicron-textured biomaterial surface reduces staphylococcal bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(1):72–81.

Kirschner CM, Brennan AB. Bio-inspired antifouling strategies. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2012;42(1):211–29.

Widawski G, Rawiso M, Francois B. Self-organized honeycomb morphology of star-polymer polystyrene films. Nature. 1994;369(6479):387–9.

Böltau M, et al. Surface-induced structure formation of polymer blends on patterned substrates. Nature. 1998;391(6670):877–9.

Lim JY, et al. Human foetal osteoblastic cell response to polymer-demixed nanotopographic interfaces. J R Soc Interface. 2005;2(2):97–108.

Karthaus O, et al. Formation of ordered mesoscopic patterns in polymer cast films by dewetting. Thin Solid Films. 1998;327:829–32.

Murthy N, et al. Self-assembled and etched cones on laser ablated polymer surfaces. J Appl Phys. 2006;100(2):023538.

Nishimoto S, Bhushan B. Bioinspired self-cleaning surfaces with superhydrophobicity, superoleophobicity, and superhydrophilicity. RSC Advances. 2013;3(3):671–90.

Chandra P, et al. UV laser-ablated surface textures as potential regulator of cellular response. Biointerphases. 2010;5(2):53–9.

Hoipkemeier-Wilson L, et al. Antifouling potential of lubricious, micro-engineered, PDMS elastomers against zoospores of the green fouling alga Ulva (Enteromorpha). Biofouling. 2004;20(1):53-63.

Bixler GD, Bhushan B. Bioinspired rice leaf and butterfly wing surface structures combining shark skin and lotus effects. Soft Matter. 2012;8(44):11271–84.

Reddy ST, et al. Micropatterned surfaces for reducing the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection: an in vitro study on the effect of sharklet micropatterned surfaces to inhibit bacterial colonization and migration of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Endourol. 2011;25(9):1547–52.

Cheng YT, et al. Effects of micro- and nano-structures on the self-cleaning behaviour of lotus leaves. Nanotechnology. 2006;17(5):1359.

Koch K, Barthlott W. Superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic plant surfaces: an inspiration for biomimetic materials. Philos T Roy Soc A. 2009;367(1893):1487–509.

Ensikat HJ, et al. Superhydrophobicity in perfection: the outstanding properties of the lotus leaf. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2011;2(1):152–61.

Scardino A, et al. Biomimetic characterisation of key surface parameters for the development of fouling resistant materials. Biofouling. 2009;25(1):83–93.

Bers AV, Wahl M. The influence of natural surface microtopographies on fouling. Biofouling. 2004;20(1):43–51.

Carman ML, et al. Engineered antifouling microtopographies – correlating wettability with cell attachment. Biofouling. 2006;22(1):11–21.

Mann EE, et al. Surface micropattern limits bacterial contamination. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3(1):1.

Bers A, et al. Relevance of mytilid shell microtopographies for fouling defence–a global comparison. Biofouling. 2010;26(3):367–77.

Zhang L, Zhao N, Xu J. Fabrication and application of superhydrophilic surfaces: a review. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2014;28(8–9):769–90.

Zhang J, Severtson SJ. Fabrication and use of artificial superhydrophilic surfaces. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2014;28(8–9):751–68.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

No original data are reported in this article.

Authors’ contributions

VBD researched and wrote the chemical-modification sections. NSM chose the topics, researched and wrote the physical-modification sections, and revised the final manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Damodaran, V.B., Murthy, N.S. Bio-inspired strategies for designing antifouling biomaterials. Biomater Res 20, 18 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-016-0064-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-016-0064-4