Abstract

Wind power is a cost-effective renewable source and can be smoothly integrated into power grid by incorporating adequate control strategies. The wind turbine prime mover, wind, is uncontrollable which makes it different from conventional generation. Therefore, it becomes very important to carry out investigations on the dynamic behavior of wind power-generating systems. In this paper, the state space model of the system is developed, optimal controllers using full-state feedback control strategy and suboptimal controllers using strip eigenvalue assignment method are designed to study the dynamic behavior of the system. Also, the optimal controllers are designed for various operating conditions using pole placement technique. Following the controller designs, the closed-loop system eigenvalues and dynamic response plots are obtained for various system states considering various operating conditions. The investigations of these reveal that the implementation of optimal controllers offers not only good dynamic performance, but also ensures system dynamic stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

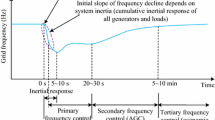

The power system dynamics is essential to be understood for stable system operation. The optimization of the existing resources is necessary for the long term stable operation of the power system. Therefore, the dynamic performance of the wind turbine generator is of concern as it affects the dynamic stability of the system to which it is connected (Al-Duwaish et al. 1999). Focus of power system engineers is currently directed to the impact of wind power on variation in frequency of system. Research efforts concentrate on the ability of wind farms to contribute in the frequency droop events by injecting active power to the grid (Khatoon et al. 2015; Attya and Hartkopf 2012; Chamorro et al. 2013). In George (2011), the impacts of wind power in the electricity grid are analyzed and a technique is presented for planning future electricity grids. In Esteban (2012), wind power uncertainty and its effects on power system adequacy are discussed. Nonlinear characteristics of wind turbine structure and generator operational behavior demand for high-quality optimal controller to ensure both stability and safe performance (Aghdam and Allahbakhsh 2014). In Jackson et al. (2015) it is shown that the optimal state estimation can be effectively used to reconstruct unknown states of a plant influenced by both system and measurement noises. In David et al. (2013) a novel scheme is presented to give dynamic wind speed estimation by measuring rotor angular velocity for small wind turbines. A compromise can be achieved between loads and variation in power without any information of the damping of wind turbine (Yolanda et al. 2012). In Epa (2011), a nonlinear controller is developed for a wind turbine generator based on nonlinear, H2 optimal control theory. Therefore, optimal controllers maximize the delivered electrical power thus maximizing the global efficiency of the energy conversion system (Munteanu et al. 2008). The wind turbine generator used is a synchronous generator (Mellow and Concordia 1969a) with a static excitation system. The transient stability signals derived from speed, terminal frequency, or power are superposed on the normal voltage signal of voltage regulator, which provides additional damping to the oscillations (Rabelo et al. 2004; Thomas et al. 1975). A wind turbine generator exhibits an unsteady input behavior mainly because of unsteady wind speeds. This unsteady behavior causes severe oscillations. The transient stability signals derived from speed and terminal frequency are superposed on the normal voltage error signal of automatic voltage regulator, thus providing damping to these oscillations (Padiyar 2006). Also, the damping can be provided using an output feedback and strip eigenvalue assignment technique. The eigenvalues location affects the dynamics of the system. Therefore, it is necessary to locate the eigenvalues at some desired positions. The exact location of all eigenvalues at each operating point is difficult to attain. But a satisfactory response for both transient and steady state can be obtained by placing all eigen values within a suitable region in complex s-plane (Kirk 1970; Sheih et al. 1986).

Wind power system under investigation

The proposed wind power system is a 1-MVA wind turbine generator, extrapolated from 100 kW unit of the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA) wind energy program at NASA-Lewis Research Centre (Thomas et al. 1975). The wind power system consists of a permanent magnet synchronous generator. The schematic diagram of the system under study is given in Fig. 1 (Al-Duwaish et al. 1999; Khatoon et al. 2015), attempts to regulate the speed and an apparent form of power. The extracted power from wind is converted into electrical power and fed to an infinite bus through a transmission link.

The system model is described in detail in author’s previous papers (Al-Duwaish et al. 1999; Khatoon et al. 2015; Khatoon et al. 2013, 2014, 2015a, b). Appendix explains the meaning and values of all abbreviations and constant. The structures of system vectors and matrices for the dynamic model of the system under consideration can be deduced using the following differential equations:

The zero damping is assumed due to electrical load characteristics; therefore

On solving the above equation, we get

which gives

Substituting the value of \(\dot{V}_{\text{R}}\) in above equation, we get

The 1.0 MVA unit is modeled to regulate the speed during its normal operation, and this can be done by changing the pitch angle as a function of speed. The pitch blade control model is defined by a second-order differential equation (Hwang and Gilber 1978).

Taking Laplace transform

Let θ 1 = θ (s) and

where the wind speed V is the source of disturbance and contributes to the variation in the generated power, it is included in the disturbance matrix ‘T’. Rest of the terms are included in the system matrix A. Now the 7th state is therefore defined as

And the 8th state is defined as

The two states θ 1 and θ 2 are restructured for the blade pitch angle θ. The state space formulation yields the system matrix ‘A’, input matrix ‘B’, and the disturbance matrix ‘T’. With the help of state space model, the system matrices can be formulated as

Methods

The classical control theory expressed in frequency domain leads to a stable system and satisfies a set of more or less arbitrary requirements. Optimal control recognizes the random behavior of the system and attempts to optimize response or stability on an average rather than with assured precision. The optimal control theory provides a comprehensive, consistent, and flexible design approach. The classical response criteria such as step response are helpful in determining what values to use in quadratic cost function weighting matrices. These weighting factors have a powerful and direct effect on achieving desired response (Lewis and Syrmos 1995; Lee and Wu 1995).

Optimal controller design using full-state feedback control strategy

To design an optimal regulator, the modern control theory requires the development of dynamic system model in state variable form. The regulator design of higher-order nonlinear system model results in complex computations. Hence, the system equations are linearized about an operating point and then the linear state regulator theory is applied to obtain the desired control law. A linear time-invariant power system in state space is represented by following differential equations:

the control law is given by

for full-state vector feedback

for output feedback problem to minimize the performance index

Subjected to system dynamic constraints Eqs. (13) and (14), the augmented cost function for the performance index J is given by

Defining Hamiltonian as

Using linear state regulator approach, let u* be an admissible control that drives the system from an initial point x 0, where * indicates that u = u*. For u* to be optimal, the variables must satisfy the following relations:

And the function H (x *, λ *, u *) must be minimum. Hence we get

From Eqs. (18) and (19), the differential equation obtained in x* and λ* must satisfy

Assuming

Substituting for the costate in terms of x in Eqs. (24) and (25), we get

Substituting x* in Eq. (25), the vector x gives the n × n matrix differential equation as

This matrix differential equation is called the Riccati equation (Ibraheem and Kumar 2004). For full-state feedback control strategy with the consideration of matrix Q as identity matrix, Eq. (29) can be rewritten in the commonly used form as

The solution of the matrix Riccati equation gives the matrix P, from which the controller gain is obtained as

Thus, the closed-loop system is defined as

where

Suboptimal controller design using strip eigenvalue assignment method

The linear systems are influenced by the locations of eigenvalues. Therefore, for a system to get good response, both in transient and steady states, it is necessary to locate all eigenvalues in desired positions. Due to approximations, it is difficult to attain the exact locations of all eigenvalues. Hence it is sufficient that all eigenvalues are placed within a suitable region in complex s-plane, using strip eigenvalue assignment method.

The linear quadratic control is used to optimize the closed-loop system, such that the eigenvalues lie within a vertical strip in the complex s-plane (Sheih et al. 1986). The output feedback controller is preferred as compared to the state feedback controller; since it is not possible to measure all the states of the system. The output feedback control law is stated as

In conventional optimal analysis, matrices Q and R are generally chosen as diagonal matrices. The system performance can be improved by shifting the eigenvalues Λ (A − BG) of the closed-loop system to a desired region. From this, the weighting matrix R is set as an identity matrix with weight states for all inputs, and Q matrix must be given. For the system to be relatively stable, h ≥ 0. Then, the closed-loop system matrix

has all its eigenvalues lying on the left side of the −h vertical line as shown in Fig. 2, where the matrix \(\tilde{P}\) is the solution of the following Riccati equation:

The unstable eigenvalues of the closed-loop system (A + h 1 in) are shifted to their mirror image position with respect to the −h vertical line (Sheih et al. 1986; Furuya and Irisawa 1999; Lee and Wu 1995). Assume two positive real values h 1 and h 2 to define an open vertical strip of (−h 1, −h 2) on the negative real axis as shown in Fig. 3, with \(\hat{A} = A + h_{1} I_{\text{n}}\). The control law is changed to be

where C + is the pseudo-inverse of C.

And

Thus, the resulting optimal closed-loop system becomes

Optimal controller design using pole placement technique

Most of the conventional design approaches specify only dominant closed-loop poles, while the pole placement design approach specifies all closed-loop poles. The pole placement technique places the poles at any desired locations by means of an appropriate state feedback gain matrix. The MATLAB software is used for placing the poles at desired locations.

Results and discussion

In this work, three different optimal controllers are designed to study the impact of varying mechanical wind power input on the generated electrical power output. In this study, the reactive power is kept constant and real power is varied in the steps of 0.35, 0.65 and 0.8 up to a maximum value of unity. The optimal controller is designed using full-state feedback controller strategy. For the design of suboptimal controller, the eigenvalue strip assignment method is considered. Then, the optimal controller using pole placement strategy is developed. The closed-loop system eigenvalues are explored as given by Tables 1, 2, and 3, for various controllers designed in this study. The inspection of these tables infers that the system stability is ensured at all operating points with all types of controllers. The stability margins are higher with the optimal regulators as compared to those offered by suboptimal controllers. The appreciable shifting of eigenvalues toward left of jω axis at P o = 0.35 as shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3, has led to increased stability margins as compared to other states. However, no appreciable change in optimal and suboptimal system eigenvalues is observed at other operating points.

The closed-loop system dynamic response plots are obtained for system state variables like angular displacement of quadrature-axis of the generator with respect to infinite bus (δ), angular frequency of the system (ω), voltage proportional to direct axis flux linkage (\(E^{\prime}_{q}\)), and blade pitch angle (θ 1), and its restructured state (θ 2) as illustrated by Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11. The values of rising time, settling time with optimal, suboptimal controller and pole placement technique are compared for varying system operating conditions are studied. The response plots obtained at P o = 1.0 for various states of the system, using various controllers are shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. From the response plots, it is revealed that both optimal and suboptimal controllers have stabilized the system performance. Moreover, the controllers designed based on pole placement technique offer an improvement in the settling time as compared to other controllers. Further, the responses at all operating conditions settle down to steady-state value. The investigations are also carried out for ω considering variation in P o as shown in Figs. 9, 10, and 11. From the inspection of these plots, it is seen that as the value of P o increases, the settling time is decreasing. The same argument is supported by Table 4. The inspection of rising time and settling time in Table 4 reveals that the optimal and suboptimal controllers offer response plots has comparable rising and settling time, whereas the controllers designed using pole placement technique has resulted in a considerable improvement change, when compared to those obtained with other controllers

Conclusions

In the present work, optimal and suboptimal controllers are designed to study the dynamic performance of the wind turbine generator model at different operating conditions. As the system dynamic model is not stable, pole placement technique is applied to place the poles of the system in stable region. The dynamic response plots and closed-loop eigenvalues are obtained. The designed controllers ensured the closed-loop system stability in the study. Furthermore, the impact of wind power on frequency of the system is seen visible. The various controllers designed in the work are found to exhibit their effect under various operating conditions.

To study the impacts on power generated with the variation in wind speed and hence power, the system is investigated at different operating conditions corresponding to different real power values, keeping the reactive power as constant. The investigations show that with all controllers, the settling time is reduced as the P o is increased. However, it is interesting to note that the settling time has reverse trend at P o = 1 p.u. The trend of the peak shows a considerable improvement, when the dynamic responses obtained using optimal controller and suboptimal controller are compared with pole placement technique.

References

Aghdam, H. N., & Allahbakhsh, F. (2014). Optimal controller for wind energy conversion systems. Sustainable Energy, Science and Education Publishing, 2(2), 57–62. doi:10.12691/rse-2-2-4.

Al-Duwaish, H. N., Al-Hamouz, Z. M., & Badran, S. M. (1999). Adaptive output feedback controller for wind turbine generators using neural networks. Electric Machines and Power Systems, 27, 465–479.

Attya, A. B., & Hartkopf, T. (2012). Penetration impact of wind farms equipped with frequency variations ride through algorithm on power system frequency response. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 40(1), 94–103.

Chamorro, H.R., Ghandhari, M., Eriksson, R. (2013). Wind power impact on power system frequency response. IEEE, North American Power Symposium (NAPS) (pp. 1–6). Manhattan. doi:10.1109/NAPS.2013.6666880.

David, G. M., Sriram, S., & Greg, S. (2013). Dynamic wind estimation based control for small wind turbines. Renewable Energy, 50, 259–267.

De Mellow, F. P., & Concordia, C. (1969a). Concepts of synchronous machine stability as affected by excitation system control. IEEE Trans, PAS, 88, 316–329.

De Mellow, F. P., & Concordia, C. (1969b). Concepts of synchronous machine stability as affected by excitation system control. IEEE Trans, PAS, 88, 316–329.

Epa, R. (2011). Non linear, optimal control of a wind turbine generator. IEEE transactions on energy conversion, issue, 2(26), 468–478.

Esteban, G. (2012). Evaluating the impact of wind power uncertainty on power system adequacy, Proceedings Of Pmaps. Istanbul.

Hardiyansyah, F.S., & Irisawa, J. (1999). Optimal Power System Stabilization via Output Feedback Excitation Control, 21, (pp. 21–28). http://hdl.handle.net/10649/555.

George, M. (2011). Analysis of the power system impacts and value of wind power. International Journal of Engineering, Science and Technology, 3(5), 46–58.

Hwang, H., & Gilber, L. J. (1978). Synchronization of wind turbine generators against an infinite bus under gusting conditions. IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems, 2(97), 536–544.

Ibraheem, & Kumar, P. (2004). A novel approach to the matrix riccati equation solution: An application to optimal control of interconnected power systems. Electric Power Components and SystemsIssue, 32(1), 33–52.

Jackson, G. N., Yan, & Dirk, L. S. (2015). Multivariable control of large variable-speed wind turbines for generator power regulation and load reduction. ScienceDirect, IFAC-Papers On-Line Issue, 48(1), 544–549.

Khatoon, S., Ibraheem, Ehtesham, R. (2013). Eigenvalue analysis of wind power generating system. International Conference on Extropianism: Towards Convergence of Human Values and Technology (pp. 205–208). Gurgaon, ISBN. 978-93-81583-79-1.

Khatoon, S., Ibraheem, Ehtesham, R. (2014). Sensitivity analysis of wind power generating system. International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics. Noida. ISBN. 978-1-4799-3080-7/14, (pp. 1316-1321).

Khatoon, S., Ibraheem, Ehtesham, R. (2015). Optimal control design for wind power systems. International Journal of Electronics, Electrical and Computational System IJEECS. Academia Science, 4, 156–163. ISSN 2348-117X.

Khatoon, S., Ibraheem, Ehtesham, R. (2015). Model order reduction technique applied to wind power generating system. National Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical And Electronics Engineering. Jamia Millia Islamia.

Khatoon, S., Ibraheem, Ehtesham, R., & Bansal, R. C. (2015). Optimal output vector feedback control strategy for wind power systems. Electric Power Components and Systems, 43(9), 1–11.

Kirk, D.E. (1970). Optimal Control Theory, Prentice-Hall, (1st ed).

Lee, Y.C., & Wu, C.J. (1995). Damping of power system oscillations with output feedback and strip eigenvalue assignment. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 10(3), 1620–1626.

Lewis, F.L., & Syrmos, V.L. (1995). Optimal Control. (2nd ed.) Wiley Eastern Limited, Wiley.com.

Munteanu, I. V., Bratcu, A. I., & Ceanga, E. (2008). Optimal control in energy conversion of small wind power systems with permanent-magnet-synchronous-generators. WSEAS Transactions on Systems and Control, 3(7), 644–653.

Padiyar, K.R. (2006). Power System Dynamics. 2nd edition. Hyderabad, B. S. Publications.

Rabelo, B., Hofmann, W., Tilscher, M., & Basteck, A. (2004). Voltage Regulator For Reactive Power Control On Synchronous Generators In Wind Energy Power Plants. Norway: NORPIE Trondheim.

Sheih, L. S., Dib, H. M., & Miccinis, B. C. (1986). Linear quadratic regulators with eigen value placemant in a vertical strip. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 31(3), 241–243.

Thomas, R., Puthoff, R., Savino, J., Johnson, W. (1975). Plans And Status Of The Nasa-Lewis Research Centre Wind Energy Projects, Joint IEEE/ASME Power Conference. Portland. Paper no. NTIS N75–21795.

Yolanda, V., Leonardo, A., Ningsu, L., Mauricio, Z., & Francesc, P. (2012). Power control design for variable-speedwind turbines. Energies, 5, 3033–3050. doi:10.3390/en5083033.

Authors’ contributions

IN gives the original idea of research problem formulation, design methodology and overall supervision of the study and analysis and interpretation of data. SK carried out co-ordination in implementing the work for conception, design, analysis and drafting of the manuscript. RE carried out experimental and simulation work of the problem and performance evaluation of the outcome of the study on the basis of experimental/ simulation results obtained. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

List of abbreviations

- E ′ q :

-

voltage proportional to direct axis flux linkage

- ω :

-

angular frequency of the system

- M :

-

moment of inertia

- D :

-

damping coefficient

- δ :

-

angle between q axis of the generator and infinite bus

- P o :

-

electrical output power

- V :

-

wind speed

- θ :

-

blade pitch angle

- T A :

-

regulator time constant

- K A :

-

regulator gain

- S E :

-

saturation function

- T F :

-

time constant of excitation system stabilizer

- K F :

-

gain of excitation system stabilizer

- A :

-

n × n system matrix

- B :

-

n × m input matrix

- T :

-

n × 1 disturbance matrix

- ξ :

-

damping ratio

- τ p :

-

actuator time constant

- θ 1, θ 2 :

-

reconstructed states for blade pitch angle

- V R :

-

regulator voltage

- V T :

-

terminal voltage

- \(K^{\prime}_{\omega } ,\,\,K^{\prime}_{v} ,\,\,K^{\prime}_{\delta }\) :

-

pitch angle regulation constants

The coefficients K 1, K 2, K 3, K 4, K 5, and K 6 are known as Heffron–Phillips constants. They depend on machine parameters and the operating conditions of the system. The Heffron–Phillip constants are defined as

K 1 = ∆T e/∆ δ│ \(E^{\prime}_{q}\)—change in electrical torque for a change in rotor angle with constant flux linkages in d-axis

K 2 = ∆T e/∆ \(E^{\prime}_{q}\)│δ—change in electrical torque for a change in d-axis flux linkages with constant rotor angle

K 3—impedance factor

K 4 = 1/K 3(∆ \(E^{\prime}_{q}\)/∆δ)—demagnetizing effect of a change in rotor angle

K 5 = ∆V t/∆δ│ \(E^{\prime}_{q}\)—change in terminal voltage with change in rotor angle for constant \(E^{\prime}_{q}\)

K 6 = ∆V t/∆ \(E^{\prime}_{q}\)│δ—change in terminal voltage with change in \(E^{\prime}_{q}\) for constant rotor angle (Mellow and Concordia 1969b).

Numerical data

x d = 2.21, \(x^{\prime}_{\text{d}}\) = 0.165, x q = 1.064, M = 19.04, D = 0, \(T^{\prime}_{\text{do}}\) = 1.942, x e = 0.3, K A = 400, T A = 0.02, K E = 1, T E = 1.3, K F = 0.03, T F = 1.0, S E = 0.64, \(K^{\prime}_{v}\) = −0.337, \(K^{\prime}_{\omega }\) = −20.94, \(K^{\prime}_{\delta }\) = −0.0055, τ p = 0.15, ξ = 0.707, K ω = −3.3, K θ = 0.118, K V = 0.337, V = 7.92, T = 4, Gu = 0.075.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ehtesham, R., Khatoon, S. & Naseeruddin, I. Optimal and suboptimal controller design for wind power system. Renewables 3, 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40807-015-0020-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40807-015-0020-2