Abstract

Exercise can improve mental health; however many tertiary students do not reach recommended levels of weekly engagement. Short-term exercise may be more achievable for tertiary students to engage in to promote mental health, particularly during times of high stress. The current scoping review aimed to provide an overview of controlled trials testing the effect of short-term (single bout and up to 3 weeks) exercise across mental health domains, both at rest and in response to an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress task, in tertiary students. The search was conducted using ‘Evidence Finder,’ a database of published and systematic reviews and controlled trials of interventions in the youth mental health field. A total of 14 trials meet inclusion criteria, six measured mental health symptoms in response to an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress task and the remaining eight measured mental health symptoms. We found that short-term exercise interventions appeared to reduce anxiety like symptoms and anxiety sensitivity and buffered against a drop in mood following an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress task. There was limited available evidence testing the impacts of exercise on depression like symptoms and other mental health mental health domains, suggesting further work is required. Universities should consider implementing methods to increase student knowledge about the relationship between physical exercise and mental health and student access to exercise facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key Points

-

Short-term exercise interventions reduce anxiety like symptoms and anxiety sensitivity in tertiary students.

-

Short-term exercise interventions buffer against a drop in mood following an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress task in tertiary students.

-

There was limited available evidence testing the impacts of exercise on depression like symptoms and other mental health symptoms in tertiary students.

Introduction

Students in tertiary education settings face a wide range of ongoing normative stressors, which can be defined as normal day to day hassles such as ongoing academic demands. Accordingly, tertiary (defined here as post-secondary education) [1] students commonly experience ongoing stress relating to their education, such as pressure to achieve high marks [2]. Stress is a clear precipitant of a wide range of mental illnesses [3, 4] and the onset of mental illness is most likely to occur during adolescence and young adulthood [5]. Therefore, interventions that promote mental health as well as target the early phases or sub-threshold symptoms are urgently required [6].

Access to facilities and programs in tertiary settings that promote mental health has the potential to improve the mental health and functioning of young people and prevent the onset and the negative impacts of mental illness [7]. Exercise is defined as the planned, structured and repetitive undertaking of physical activity for the purposes of maintaining or improving health or skill-related components of physical fitness [8, 9]. Our previous work demonstrates that exercise can improve mental health in young people [10]; however many young people fail to reach the weekly recommended levels of exercise participation [11,12,13]. Disengagement from exercise, physical activity and sporting clubs occurs during adolescence [14, 15], with more than 80% of adolescents and 25% of adults worldwide being insufficiently active [16]. When individuals transition from secondary school to tertiary education, they can experience a further decline in exercise levels [17,18,19].

Rationale

Short-term exercise is defined as any exercise intervention that is shorter than 3 weeks in duration [20, 21]. Short-term exercise may be an effective way to protect against mental health concerns in tertiary education settings, including during periods of high stress, such as exam periods [22]. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of all populations and age groups show that short-term exercise, including a single bout of exercise, can reduce symptoms of anxiety [23] and increase feelings of energy [24], while in healthy adults single bouts of exercise increase performance on memory tasks [25]. The potential of short-term exercise as a mental health promotion strategy in tertiary students, specifically, remains unknown.

Objectives

The review addressed the research question: What is known about the impact of short-term exercise for mental health promotion in tertiary students? ‘Mental health’ encompasses mental health symptoms as collected using quantitative outcome measures of mental ill-health symptom severity as well indicators of mental health, including well-being and quality-of-life [26]. We provide an overview of controlled trials that assess the effect of short-term exercise on mental health, in tertiary students.

The objectives were:

-

1.

Examine the range/extent of outcomes from short-term exercise interventions on mental health in tertiary students;

-

2.

Collate mental health data and provide an overview of the effect of short-term exercise on mental health in tertiary students.

Methods

Protocol/Registration

This review was reported and conducted in line with PRISMA-ScR guidelines for scoping reviews [27]. A review protocol was not registered or published.

Eligibility Criteria

Study eligibility criteria were as follows: the sample comprised of tertiary students (mean age under 25.9 years); studies were published between 1980 and 2019 [28]; included an exercise intervention and a comparison condition; the exercise intervention/s lasted less than 3 weeks in duration [20, 21]; study designs were randomised controlled trials [RCTs] or non-randomized controlled trials and published in English and reported on at least one of the following mental health outcomes:

-

Depression symptoms;

-

Anxiety symptoms, or trait anxiety measures;

-

Substance use or symptoms;

-

Bipolar symptoms;

-

Eating disorder symptoms;

-

Trauma or stressor-related symptoms;

-

General psychological distress;

-

Wellbeing/functioning: Quality of life; Functioning (social, educational, vocational, employment).

Studies were excluded if: they were unpublished or comprised of a population diagnosed with a mental disorder or illness. This is because we have reviewed exercise and physical activity as a treatment for mental illness in our companion paper [29].

Information Sources

Searches were conducted using ‘Evidence Finder’ (www.orygen.org.au). ‘Evidence Finder’ is a database of published systematic reviews and controlled trials of interventions delivered for youth mental health [28, 30]. The ‘Evidence Finder’ is a Federally funded, initiative designed to reduce duplication in method to enable more rapid translation of research evidence. It aims to facilitate evidence-based practice by providing a comprehensive summary of the extent and distribution of existing research. It achieves this through a rigorous process by which intervention trials and systematic reviews published in the area of youth mental health are systematically searched for and compiled into a central resource. It offers rapid access to the best available evidence and the vast coverage offered by the evidence mapping methodology provides an overall snapshot of where evidence exists and where it is lacking. Therefore, this easy access to the current body of evidence can inform and guide new research agendas towards addressing the gaps in our knowledge of intervention for mental health promotion among young people

In order to comprehensively and systematically assemble and appraise evidence for short-term physical activity across numerous mental-health outcomes, a mapping methodology was selected.

The database is populated annually using systematic searches of the following databases: Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library and MEDLINE (see [28, 30] for detailed methodology). It includes prevention, treatment and relapse‐prevention studies. It also includes interventions delivered to young people (6–25 years), published between 1980 and 2019 and assessing the following mental health symptoms: bipolar, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, suicide-self harm, substance use and psychosis. It contains RCTs and quasi‐randomised studies as well as systematic reviews and/or meta‐analyses, published in English.

The following criteria were applied to the ‘Evidence Finder’ search engine: (1) ‘all’ mental health/substance use problems; (2) ‘all’ stages of illness; (3) ‘complementary and alternative interventions’ treatment/interventions, followed by ‘Physical activity/exercise’ (4) ‘all’ for Publication Date; (5) and ‘non’ for keywords. Advanced options were also selected to include randomized/ controlled clinical trials and systematic reviews.

Search

A single author [MP] conducted a search of the literature using the ‘Evidence Finder’ in July 2018 (updated in May 2020). All studies that had been classified within ‘Evidence Finder’ as ‘Physical activity/Exercise’ and published between 1980 and 2019 were assessed. No other restrictions were applied to the ‘Evidence Finder’ search as the scoping review sought to synthesise a large number of outcomes across multiple mental health concerns. Moreover, the reference lists of identified literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses were searched for suitable primary research. In addition the studies identified using ‘Evidence Finder,’ the reference lists of reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses retrieved from the ‘Evidence Finder’ were also checked to identify additional relevant studies.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

Two authors independently undertook title and abstract screening (MP, AP). All full texts were reviewed independently by at least two authors (MP, AP, MC). There were no conflicts requiring resolution by a third author.

Data Charting Process

Data charting [31] were undertaken by one author (MP) using the extraction forms shown in Tables 1 and 2. All extracted data were checked for accuracy by a second author (TC, AB). Data were obtained only and directly from the articles.

Two assessors (NS, RP) reviewed studies for subjective (perceived exertion ratings) and objective measures of exercise intensity (heart rates [HR], %maximal HR, %HR reserve, %1-repetition maximum, percent of maximal-oxygen-uptake [%VO2max]). Using these, the interventions were classified by intensity: (1) light-intensity, (2) light-to-moderate-intensity, (3) moderate-intensity, (4) moderate-to-vigorous-intensity, or (5) vigorous-intensity for resistance exercise [47] and aerobic exercise [21]. If possible, we attempted to estimate intensity based on the compendium of exercise energy expenditure, where the interventions were insufficiently described [48]. We did not contact authors for further information when insufficient information was provided in the published articles.

Data Items

The following data were extracted: study design type, setting of study, country of study origin, sample size, participants and mean age, tools employed to measure mental health domain, the mental health domain assessed, assessment time points, overall findings, and if intention to treat analysis was used (Table 1). We also extracted characteristics of the exercise intervention and control intervention, including the delivery format, duration and frequency of the intervention and what personnel delivered the intervention (Table 2).

Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

As scoping reviews are generally conducted to provide an overview of the existing evidence regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias, the included sources of evidence are typically not critically appraised, as per PRISMA-ScR guidelines [27], and we, did not conduct a risk of bias assessment.

Synthesis of Results

We used the mental health domain as the common analytical framework in our ‘descriptive-analytical’ approach [31]. The combination of exercise intensity (light, moderate or vigorous) and duration (minutes/week) determines the session and intervention dose of exercise interventions. We focused on exercise intensity rather than dose, due to heterogeneity of the duration of interventions and given that exercise intensity is strongly linked to affective responses and sustainability [49, 50].

Results

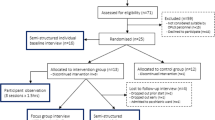

Selection of Sources of Evidence

A total of 112 records were returned using the ‘Evidence Finder.’ Additional articles (n = 22) were searched for and identified by going through the retrieved searching reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses identified through ‘Evidence Finder’ (Fig. 1). In total, 15 studies were included; however two of these studies [41, 42] report different outcomes from the same trial and therefore were combined in this review, resulting in inclusion of 14 studies.

Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

Six of these studies measured mental health symptoms in response to an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress task [32,33,34, 42, 45, 46], and the remaining eight measured mental health [35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Ten studies delivered a single bout of exercise [32, 34,35,36,37, 39, 40, 44,45,46] and four delivered short-term (under 3 weeks) exercise sessions or programs [33, 38, 41,42,43]. All studies were RCTs. Seven of the 12 studies included as an eligibility criteria young people with elevated symptomology at baseline; two with elevated anxiety like symptoms [34, 37], four with high anxiety sensitivity or proneness [36, 38, 41,42,43], and one with elevated eating disorder symptoms [44]. In the remaining seven studies [32, 33, 35, 39, 40, 45, 46] tertiary students were not required to have elevated mental health symptoms for study inclusion.

Results of Sources of Evidence

Extracted data are shown in Tables 1 and 2. As shown in Table 2, five interventions were delivered individually, and the remaining seven did not state the method of delivery.

Types of Interventions

Figure 2 shows that moderate to vigorous intensity exercise interventions were the most frequently studied, and were most commonly running/jogging on a treadmill. Vigorous intensity interventions were also commonly studied, and included resistance exercise and jogging/sprinting. Moderate intensity exercises were also examined, and included cycling, walking/jogging and resistance exercises.

Synthesis of Results

Anxiety Like Symptoms

Five studies assessed the impact of short-term exercise on anxiety like symptoms [35,36,37,38,39], and 80% (4/5) indicated that exercise reduced anxiety like symptoms [35, 36, 38, 39]; however, one of these studies did not include a non-exercise-based control group [35]. In another of these studies, a 2-week-long vigorous intensity aerobic intervention reduced state anxiety compared to a light-to-moderate intensity intervention, in tertiary students with high proneness to anxiety [38]. In another study involving tertiary students with high proneness to anxiety, a single bout of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic exercise decreased anxiety like symptoms, as compared to no intervention [36]. In the third study, a single bout of moderate-intensity resistance-based exercise reduced state anxiety, compared to video watching, in healthy female tertiary students [39]. The single study that found no influence of a light intensity aerobic intervention on anxiety like symptoms, compared exercise to involuntary, passive cycling movement, during which the participants' legs were moved using a passive motorized cycle [37].

Anxiety Proneness or Sensitivity

Three studies assessed anxiety proneness or sensitivity, defined as the fear of the sensations that accompany anxiety, such as elevated heart rate, and 100% (3/3) found that short-term exercise decreased anxiety sensitivity [38, 42, 43]. Two studies assessed the impact of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic interventions, one reported that a 2-week-long intervention reduced anxiety sensitivity in tertiary students with high anxiety sensitivity scores, compared to no-intervention [43] and the other reported that a single bout of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise reduced anxiety sensitivity, compared to a wait-list (WL) control [41, 42]. In one of these studies, changes in depressed and anxious mood were mediated by the effects of the single bout of exercise on anxiety sensitivity [42]. The third study reported that both a 2-week-long vigorous aerobic intervention and a 2-week-long light-to-moderate intensity intervention reduced anxiety sensitivity from pre-to-post intervention, but that the vigorous-intensity intervention resulted in a more rapid reduction in anxiety sensitivity in tertiary students who had high anxiety sensitivity. This study compared two exercise interventions however so it lacked a non-exercise control group [38].

Mood States

Two studies assessed mood states and neither found that exercise influenced mood states [37, 44]. One study found no effect of a single bout of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise on mood states, compared to a rest condition, in female tertiary students with a high drive for thinness [44]. The remaining study similarly found no effect of a stand-alone session of light intensity aerobic exercise, compared to involuntary, passive cycling movement, during which the participants' legs were passively moved, using motorized cycle, among tertiary students with high anxiety like symptoms [37].

Depression Like Symptoms

Two studies assessed depression like symptoms [35, 42]. One study reported that a single bout of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic exercise decreased depression like symptoms in tertiary students with elevated depression, anxiety and stress symptoms at baseline, as compared to a wait list control group [42]. The second study found that all four exercise interventions assessed depression like symptoms from pre- to post-intervention; however this study did not include a non-exercise-based control group [35].

Outcomes Assessed by a Single Study

Another study found that a single session of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic exercise did not influence eating disorder symptoms in female tertiary students with a high drive for thinness, compared to rest [44]. A single bout of vigorous intensity resistance exercise increased anger at 5 min following exercise, compared to no intervention, in health tertiary students [32].

Mental Health Symptoms in Response to an Experimentally Manipulated Laboratory Stressful Task

Anxiety Like Symptoms Following an Experimentally Manipulated Laboratory Stressful Task

Three studies tested the impact of short-term exercise on anxiety like symptoms following a stressful task [32,33,34] and 33% (1/3) indicated that exercise reduced anxiety like symptoms. In one of these studies, a single session of vigorous-intensity resistance-based exercise increased self-reported anxiety like symptoms 5 min following exercise, but reduced anxiety like symptoms at 30 and 45 min following exercise, compared to a no-intervention control group, in healthy students [32]. There was no effect of a single aerobic exercise session on anxiety like symptoms following a memory task, compared to no intervention, in students with a sedentary lifestyle [33]. There was similarly no effect of a single bout of moderate-vigorous intensity aerobic exercise on anxiety like symptoms, following a speaking challenge, compared to rest, in individuals with elevated self-reported anxiety like symptoms [34].

Mood States Following an Experimentally Manipulated Stressful Task

Two studies assessed mood states in response to a laboratory stress task in the form of a test of mental ability (the digits backward test), and both found a single session of exercise prior to completing the stressful task improved mood states, in active and inactive tertiary students [45, 46]. A single session of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise improved mood states, as compared to wait list group, in the absence of any observed changes in cardiovascular reactivity [45], as did a single session of light-moderate aerobic exercise, compared to rest, in healthy female tertiary students [46].

Affect Following an Experimentally Manipulated Stressful Task

Two studies assessed affect following either recall and description of extremely upsetting experiences [32], or a recognition memory task [33]. One of these studies found that a single session of vigorous intensity resistance-based exercise following viewing of negative imagery, blunted decreases in positive affect, compared to no intervention, in healthy university students [32]. In the second study, a single aerobic exercise session had no effect on affect following a memory task, compared to no intervention, in tertiary students with a sedentary lifestyle [33].

Stress Following an Experimentally Manipulated Stressful Task

A single aerobic exercise session did not reduce stress or depression like symptoms, in response to a recognition memory task, in individuals with a sedentary lifestyle and compared to no intervention, in tertiary students with a sedentary lifestyle [33].

Discussion

The finding of the current scoping review indicates that short-term exercise may be beneficial for mental health promotion among tertiary students. Therobicis is an important finding as short-term exercise may buffer against the detrimental effects of stress during periods of high stress in tertiary students who do not engage in regular exercise. Importantly, a previous meta-analysis demonstrated that lifestyle interventions targeting physical activity in tertiary settings significantly increased the amount of moderate physical activity undertaken by tertiary students, indicating that tertiary institutions are suitable settings for implementing such interventions to promote physical activity and exercise [51]. Short-term exercise may be more achievable for tertiary students to engage in, compared to achieving an ongoing exercise regime, to promote mental health, particularly during times of high stress.

Summary of Evidence

Mental Health

The available evidence indicates that short-term exercise results in improvements in anxiety like symptoms [36, 38, 39] and anxiety sensitivity or proneness [38, 42, 43], but not mood states [37, 44]. This is consistent with our previous scoping reviews examining the effects of longer term (longer than 3 weeks) exercise and physical activity interventions on mental health [10]. In our earlier scoping review, we found that moderate-to-vigorous-intensity and light-intensity exercise and physical activity reduce anxiety like symptoms and improve mood states, in healthy young people and young people with sub-threshold mental health symptoms [10]. In individuals with a mental illness, we previously found that light-to-moderate intensity exercise reduces anxiety, and moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercise can improve mood states [29], which may be an important consideration in that immediate changes in mood states may increase motivation or adherence to continued engagement in exercise [52, 53]. In particular, the current findings are consistent with previous work showing that vigorous-intensity exercise, but not light-intensity exercise, can reduce remission rates and irritability and improve mood states, in women with generalised anxiety disorder, compared to a waitlist control group [54], but does not reduce depression, anxiety like symptoms or worry [55]. It is still unclear exactly why exercise may be beneficial for anxiety like symptoms in particular and this is a worthwhile area of future inquiry. There is limited evidence regarding the impact of short-term exercise on other mental health concerns, such as eating disorder symptoms and stress, indicating that these are areas that require further investigation.

Exercise and Mood States Following an Experimentally Manipulated Stressful Task

The available evidence indicates that a single bout of exercise can improve mood states in response to an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress task [45, 46], indicating that exercise may be beneficial for mood when students are coping with stressful situations such as exam pressures.

Intervention Characteristics

There were too few studies identified in the current scoping review to determine if outcomes vary depending on intervention intensity or approach. A previous systematic review of interventions promoting physical activity among university students, however, concluded that interventions would do well to address a number of behavioural determinants and argued that personalised approaches should be considered [56]. These authors highlight that many exercise interventions delivered in tertiary settings are not individualised and do not assess the unique needs of participants such as motives to engage in exercise interventions, skills required and self-regulatory techniques [56]. It is unknown if such considerations are relevant to achieve adherence to and engagement with short-term exercise interventions, and this could be an area of future investigation.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review has a number of strengths. It is the first to examine the effects of short-term exercise on mental health concerns and in response to an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress test, in young people in tertiary education settings. It was conducted in concordance with and reported according to PRISMA guidance. The review also has some limitations. Six studies compared exercise to a wait-list group or to an additional exercise group, rather than to a non-exercise-based comparison group [33, 35, 38, 40,41,42, 45]. Therefore, while these studies can contribute to the literature in terms of demonstrating if short term exercise can result in pre-post changes in mental health measures, and if different exercise types and intensities are associated with benefits, without a non-exercise-based control group, it is unknown if the observed effects result from the exercise intervention, or from non-specific factors other than the intervention, such as time/attention effects [57]. In the current study, the exercise interventions are described only in terms of intensity; however there may be other potentially important aspects other than intervention intensity that influence mental health symptoms, such as exercise duration, adherence and the specific method of exercise employed, which we have not considered. As scoping reviews are generally conducted to provide an overview of the existing evidence regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias, the included sources of evidence are typically not critically appraised, as per PRISMA-ScR guidelines; however without conducting a risk of bias assessment [58], the quality of the included studies is unknown.

Future Directions

Some universities are embedding information of the relationship between mental health and physical activity into student mental health strategies, such as Victoria University, Melbourne which states that it aims to, ‘raise awareness amongst all staff and students of the enablers of good mental health and ensure easy access to further support and guidance on these enablers. Enablers can include sleep, diet/alcohol, accommodation, finance, sport, physical activity and study skills [59].’ Therefore, tertiary education settings might consider implementing methods to increase student access to exercise facilities and student knowledge of the relationship that exists between exercise and mental health. Indeed, university researchers and educators have skills to develop and trial methods to promote university student mental health; however at present many universities are developing policies without national leadership, guidance or resourcing and support [60]. This highlights a need for partnerships between governments, mental health and higher education service delivers which incorporate data collection on university student mental health.

Conclusion

This review examined the breadth and outcomes of intervention studies assessing the effects of short-term exercise on mental health in tertiary students. We found that short-term exercise interventions can reduce anxiety like symptoms and anxiety proneness or sensitivity as well as improve mood states in response to an experimentally manipulated laboratory stress test. Positive effects of short-term exercise on additional mental health outcomes in tertiary students were also identified; however there were very few studies available. This indicates that the research regarding the impact of short-term exercise on mental health in tertiary students is currently lacking.

In future research it would be worthwhile exploring the relationship between short and longer-term exercise and how they may relate to each other, in order to maximise the benefits for tertiary students' mental health. The current findings may be useful for consideration in policies and strategies to promote mental health in tertiary students, as although the evidence-base is currently limited, it is preferable that strategies be based on the evidence available, notwithstanding the limitations.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- 1RM:

-

1 Repetition maximum

- AET:

-

Aerobic exercise training

- AET-high:

-

Aerobic exercise training low intensity

- AET-low:

-

Aerobic exercise training low intensity

- ASI:

-

Anxiety Sensitivity Index

- ASI-R:

-

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-Revised

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BG:

-

Between group difference

- bpm:

-

Beats per minute

- CBD:

-

Cannot be determined

- E:

-

Exercise

- FU:

-

Follow-up

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ITT:

-

Intention to treat analysis

- LIET:

-

Low intensity exercise training

- MOD:

-

Moderate

- MHR:

-

Maximum heart rate

- mph:

-

Miles per hour

- mths:

-

Months

- M :

-

Mean

- m:

-

Minutes

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- NS:

-

Not stated

- n :

-

Sample size

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PP:

-

Pre-post intervention

- PE:

-

Physical education

- Reps:

-

Repetitions

- RPE:

-

Rating of perceived exertion

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- RET:

-

Resistance exercise training

- RET-mod:

-

Resistance exercise training moderate intensity

- RET-high:

-

Resistance exercise training high intensity

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- TAU:

-

Treatment as usual

- VIG:

-

Vigorous

- VO2:

-

Oxygen consumption

- wk:

-

Week

- WL:

-

Waitlist

- yrs:

-

Years

References

UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics; 2012.

Pascoe MC, Hetrick SE, Parker AG. The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2020;25(1):104–12.

Compas BE, Orosan PG, Grant KE. Adolescent stress and coping: implications for psychopathology during adolescence. J Adolesc. 1993;16(3):331–49.

Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):87–127.

Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiolac S, Alonsod J, Lee S, Bedirhan UT. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–64.

McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2006;40:616–22.

Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Hickie I, Purcell R, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Early identification and intervention in depressive disorders: towards a clinical staging model. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(5):263–70.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC: 1974). 1985;100(2):126–31.

Thompson PD, Arena R, Riebe D, Pescatello LS, American College of Sports M. ACSM’s new preparticipation health screening recommendations from ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, ninth edition. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(4):215–7.

Pascoe M, Bailey AP, Craike M, Carter T, Patten R, Stepto N, et al. Physical activity and exercise in youth mental health promotion: a scoping review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1):e000677.

The Department of Health. Australia's Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines and the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines Canberra: Australain Governemnt; 2019. Available from https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines.

Services. UDoHaH. Physical activity guidelines for americans. 2nd ed. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

Bull FtEWG. Physical activity guidelines in the U.K. review and recommendations. Loughborough: Loughborough University; 2010.

Zimmermann-Sloutskis D, Wanner M, Zimmermann E, Martin BW. Physical activity levels and determinants of change in young adults: a longitudinal panel study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(2):1–13.

Eime RM, Harvey JT, Sawyer NA, Craike MJ, Symons CM, Payne WR. Changes in sport and physical activity participation for adolescent females: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:533.

WHO. Physical activity: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity.

Bray SR, Born HA. Transition to university and vigorous physical activity: implications for health and psychological wellbeing. J Am Coll Health. 2004;52(4):181-88. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.52.4.181-188.

Wengreen HJ, Moncur C. Change in diet, physical activity, and body weight among young-adults during the transition from high school to college. Nutr J. 2009;8:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-8-32.

Deforche B, Van Dyck D, Deliens T, et al. Changes in weight, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and dietary intake during the transition to higher education: a prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0173-9.

American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):975–91.

Norton K, Norton L, Sadgrove D. Position statement on physical activity and exercise intensity terminology. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(5):496–502.

Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-term adherence to health behavior change. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2013;7(6):395–404.

Ensari I, Greenlee TA, Motl RW, Petruzzello SJ. Meta-analysis of acute exercise effects on state anxiety: an update of randomized controlled trials over the past 25 years. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):624–34.

Loy BD, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effect of a single bout of exercise on energy and fatigue states: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fatigue. 2013;1(4):223–42.

Lambourne K, Tomporowski P. The effect of exercise-induced arousal on cognitive task performance: a meta-regression analysis. Brain Res. 2010;1341:12–24.

Kelly P, Williamson C, Niven AG, Hunter R, Mutrie N, Richards J. Walking on sunshine: scoping review of the evidence for walking and mental health. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(12):800–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Callahan P, Purcell R. Evidence mapping: illustrating an emerging methodology to improve evidence-based practice in youth mental health. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(6):1025–30.

Pascoe MC, Bailey AP, Craike M, et al Exercise interventions for mental disorders in young people: a scoping review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6:e000678. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000678.

De Silva S, Bailey AP, Parker AG, Montague AE, Hetrick SE. Open-access evidence database of controlled trials and systematic reviews in youth mental health. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(3):474–7.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Bartholomew JB. The effect of resistance exercise on manipulated preexercise mood states for male exercisers. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1999;21(1):39–51.

Hopkins ME, Davis FC, VanTieghem MR, Whalen PJ, Bucci DJ. Differential effects of acute and regular physical exercise on cognition and affect. Neuroscience. 2012;215:59–68.

Julian K, Beard C, Schmidt NB, Powers MB, Smits JA. Attention training to reduce attention bias and social stressor reactivity: an attempt to replicate and extend previous findings. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(5):350–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.015

Mothes H, Leukel C, Jo HG, Seelig H, Schmidt S, Fuchs R. Expectations affect psychological and neurophysiological benefits even after a single bout of exercise. J Behav Med. 2017;40(2):293–306.

Smits JAJ, Meuret AE, Zvolensky MJ, Rosenfield D, Seidel A. The effects of acute exercise on CO2 challenge reactivity. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(4):446–54.

Lindheimer JB, O’Connor PJ, McCully KK, Dishman RK. The effect of light-intensity cycling on mood and working memory in response to a randomized, placebo-controlled design. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(2):243–53.

Broman-Fulks JJ, Berman ME, Rabian BA, Webster MJ. Effects of aerobic exercise on anxiety sensitivity. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(2):125–36.

Focht BC, Koltyn KF, Bouchard LJ. State anxiety and blood pressure responses following different resistance exercise sessions. Int J Sport Psychol. 2000;31(3):376–90.

Mason JE, Asmundson GJG. A single bout of either sprint interval training or moderate intensity continuous training reduces anxiety sensitivity: a randomized controlled trial. Ment Health Phys Act. 2018;14:103–12.

Medina JL, DeBoer LB, Davis ML, Rosenfield D, Powers MB, Otto MW, et al. Gender moderates the effect of exercise on anxiety sensitivity. Ment Health Phys Act. 2014;7(3):147–51.

Smits JA, Berry AC, Rosenfield D, Powers MB, Behar E, Otto MW. Reducing anxiety sensitivity with exercise. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(8):689–99.

Broman-Fulks JJ, Storey KM. Evaluation of a brief aerobic exercise intervention for high anxiety sensitivity. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2008;21(2):117–28.

Fallon EA, Hausenblas HA. Media images of the “ideal” female body: can acute exercise moderate their psychological impact? Body Image. 2005;2(1):62–73.

Roth DL. Acute emotional and psychophysiological effects of aerobic exercise. Psychophysiology. 1989;26(5):593–602.

Roth DL, Bachtler SD, Fillingim RB. Acute emotional and cardiovascular effects of stressful mental work during aerobic exercise. Psychophysiology. 1990;27(6):694–701.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand, et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–59.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:498–504.

Ekkekakis P, Parfitt G, Petruzzello SJ. The pleasure and displeasure people feel when they exercise at different intensities decennial update and progress towards a tripartite rationale for exercise intensity prescription. Sports Med. 2011;41(8):641–71.

Lee HH, Emerson JA, Williams DM. The exercise-affect-adherence pathway: an evolutionary perspective. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1285.

Plotnikoff RC, Costigan SA, Williams RL, Hutchesson MJ, Kennedy SG, Robards SL, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting physical activity, nutrition and healthy weight for university and college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys. 2015;12:1–10.

Hughes CW, Barnes S, Barnes C, DeFina LE, Nakonezny P, Emslie GJ. Depressed adolescents treated with exercise (DATE): a pilot randomized controlled trial to test feasibility and establish preliminary effect sizes. Ment Health Phys Act. 2013;6(2):119–31.

Brown SW, Welsh MC, Labbe EE, Vitulli WF, Kulkarni P. Aerobic exercise in the psychological treatment of adolescents. Percept Mot Skills. 1992;74(2):555–60.

Herring MP, Jacob ML, Suveg C, Dishman RK, O’Connor PJ. Feasibility of exercise training for the short-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;81(1):21–8.

Herring MP, Jacob ML, Suveg C, O’Connor PJ. Effects of short-term exercise training on signs and symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Ment Health Phys Act. 2011;4(2):71–7.

Maselli M, Ward PB, Gobbi E, Carraro A. Promoting physical activity among university students: a systematic review of controlled trials. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(7):1602–12.

Price DD, Finniss DG, Benedetti F. A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: recent advances and current thought. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:565–90.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 Cochrane; 2019. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Victoria Univerity. Student mental health stratergy 2018–2020 Melbourne: Victoria Univeristy; 2018. Available from https://www.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/student-mental-health-strategy.pdf.

Orygen TNCoEiYMH. Under the radar. The mental health of Australian University students. Melbourne: Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health; 2017.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our recently deceased co-author, Professor Nigel Stepto, who made a significant contribution to this work and to the field of physical activity, exercise and wellbeing, more generally. He will be remembered warmly.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MCP, AP, MC conducted the literature search; MCP designed the figures and tables; all authors contributed to study design; MCP, AP, AB, NS, RP, TC contributed to data collection; MCP, AP, AB, NS, RP, TC contributed to data analysis and data interpretation; all authors contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors agree to this paper being published.

Competing Interests

Michaela Pascoe, Alan Bailey, Melinda Craike, Tim Carter, Rhiannon Patten, Nigel Stepto and Alex Parker declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pascoe, M.C., Bailey, A.P., Craike, M. et al. Single Session and Short-Term Exercise for Mental Health Promotion in Tertiary Students: A Scoping Review. Sports Med - Open 7, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00358-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00358-y