Abstract

Background

Malnutrition is a universal problem in cancer patients renowned as an important factor for increased morbidity, decreased quality of life and high mortality. Early diagnosis of malnutrition risk through nutrition screening followed by comprehensive and timely interventions reduces mortality associated with malnutrition. The Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PGSGA) method has been proved efficient in identifying cancer patients with nutrition challenges and guiding appropriate interventions. However this tool has not been adopted in management of cancer patients in Kenya. The aim of the study was to assess and describe nutrition status of cancer outpatients receiving treatment at Kenyatta National Hospital Hospital (KNH) and Texas Cancer Centre (TCC).

Methods

The study adopted a hospital based descriptive cross sectional study. Cancer outpatients with confirmed stage 1–4 cancers, physically stable, aged 18 years and above and receiving cancer treatment were recruited and assessed using Scored PGSGA tool. Proportions, measures of central tendency and pearsons’ chi-square test were used in statistical analysis.

Results

Among the 471 participants assessed, 71.8% were female and 28.2% male. Most participants had stage 2, 3 and 4 cancers at 27.2%, 27.2% and 24.3% respectively. Highest proportion of participants had breast (29.7%) and female genital cancers (22.9%). Sixty nine percent of participants were well nourished (SGA-A), 19.7% moderately malnourished (SGA-B) and 11.3% severely malnourished (SGA-C) and this difference was statistically significant. The mean PGSGA score was 6.76 (SD 5.17). Based on the score, 33.8% of participants required critical nutrition care, 34.8% symptoms management, 14.2% constant nutrition education and pharmacological intervention while 17.2% required routine assessments and reassurance. More (m;54.7%, f; 45.3%) males than females were severely malnourished(SGA-C) and this was statistically significant (P < 0.001).Prevalence of severe malnutrition was highest among participants with digestive organ cancers (49.1%) followed by those with lip cancer (17%) and the least prevalence reported in those with Karposi Sarcoma (0%). Most of stage 4 participants were moderately (37.5%) and severely (29.4%) malnourished.

Conclusions

The Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment is able to identify cancer patients both at risk of malnutrition and those severely malnourished. It also provides a guideline on the appropriate nutrition intervention hence an important tool in nutrition management of cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malnutrition is a universal problem in cancer patients renowned as an important factor for increased morbidity, decreased quality of life, decreased survival and high mortality [1]. In addition, malnutrition has been observed to negatively impact patients’ reaction to treatment, elevate treatment side effects, disrupt consecutive treatment regimens, increase hospital stay, weaken functionality and immunity of patient hence affecting survival rates of the patients [2] Malnutrition and weight loss are prevalent in 20–80% of cancer patients [3, 4]. It is characterized with depression, fatigue and malaise which also significantly impact patient well-being and is highly associated with significant healthcare costs [2]. Under nutrition often occurs as a result of an array of factors including reduced food intake, adverse effects from the anticancer treatment and altered metabolic processes due to the tumor [1]. Therefore, early recognition and detection of risk for malnutrition through nutrition screening followed by comprehensive nutrition assessment and timely interventions should be considered a valuable measure within the overall oncology strategy [5].

Scored Patient Generated Subjective Global assessment tool (PGSGA) [6] has been validated and accepted by the oncology nutrition dietetic group of American Dietetic Association as a standard tool for nutrition assessment of patients with cancer [3, 7]. It is a simple bedside method of assessing the risk of malnutrition and identifying those who would benefit from nutritional support hence considered to be the most appropriate tool for detecting malnutrition in cancer patients [8]. PGSGA relies majorly on weight history, changes in dietary intake of the patients, presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, functionality, and physical examination. The patients are then classified into three categories; Well nourished (SGA-A), Moderately undernourished or suspected malnutrition (SGA-B) and severely undernourished (SGA-C). The resulting total score guides the intervention plan [9]. Despite being identified as an ideal method of assessing nutrition status of cancer patients, the tool has not been utilized for the nutrition assessment of cancer patients in Kenya. The study therefore aimed to assess and describe the nutrition status of cancer outpatients receiving treatment at Kenyatta National Hospital and Texas Cancer Centre using the PGSGA tool.

Methods

Study design

A hospital based descriptive cross sectional study was adopted to assess and describe the nutritional status of cancer outpatients receiving treatment at Kenyatta National Hospital and Texas Cancer Centre.

Study population

Cancer outpatients with established stage 1–4 cancers, aged 18 years and above who were physically stable with no active illness and body weakness were recruited while excluding the terminally ill patients and those who declined to consent.

Sample size estimation and allocation

A sample of 512 participants was recruited for the study with a total of 312 and 200 participants from KNH and TCC respectively. The Fishers et al. formula [10] was used to calculate the required minimum sample size of 385 with 95% confidence interval, error margin of 0.05 based on an assumed prevalence of malnutrition of 50% among cancer patients in Kenya. The required n = 385 and assuming 10% non response rate, the study aimed at recruiting a minimal sample of 424 patients. The calculated sample size was distributed between the two facilities using square root allocation method to ensure that the two facilities were equally represented based on the number of patients received per facility per year. Participants were recruited on the days they visited the hospital for treatment. The nurses list of attendance for patients was used to select the patients using systematic random sampling method where every third patient was recruited until the desired sample size was achieved. Seven qualified nutritionists with past experience in nutrition assessments and health facility based data were recruited as research assistants from a pool of existing institutional personnel database. In addition, four hospital personnel (one nurse and one health records officer per facility) were recruited to assist in patient record retrieval, patient identification and coordination. The team was trained on how to administer the PGSGA tool, assess the patients and ethical considerations during data collection.

Methodology

The Standard PGSGA tool developed and validated for use in ambulatory oncology settings was used for data collection. Sections on weight history, changes in dietary intake, presence of nutrition impacting symptoms and functionality were assessed by trained nutritionists while physical examination was carried out by experienced nurses at both facilities. Patients current weight and height were measured using SECA Scales and stadiometers respectively. Information on dietary intake and nutrition symptoms was reported by participants while information on weight history, use of corticosteroids, type of cancer stage and any other illness was retrieved from participants medical records. Each participant was classified as well nourished (SGA-A), moderately malnourished (SGA-B) and severely malnourished (SGA-C). The total PGSGA score was determined by summing up the scores for all the sections (weight history, dietary intake, nutrition impact symptoms). The scores were further classified according to corresponding nutrition intervention such that a score of 0–1 inicated regular reassessment and reassurance during treatment; 2–3- Patient and family education with pharmacological intervention; 4–8 intervention on symptom management by dietitian and a score of >9; indicates a critical need for nutrient support options [9]. Table 1 shows the PGSGA Global assessment categories used in patient classification.

Data on clinical characteristics of the participants including the cancer staging and type were extracted from participants’ medical records. In Kenya, cancer staging is carried out using the Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM)Staging system [11]. Cancer classification is established by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3) which classifies cancer based on either the tissue from which the cancer originates (histology types), primary site or the location in the body where cancer first developed [12].

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in MS Access database, cleaned and exported to SPSS version 20.0 software for data analysis. Exploratory data analysis techniques were used at the initial stage of analysis to uncover the data structure and identify outliers or unusually entered values. Proportions were used to summarize categorical variables and measures of central tendency for continuous variables. Pearson’s Chi-square test or fisher exact test was used to assess the relationship between dependent and categorical variables. The threshold for statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

A total of 41 patients whose weight history details were missing were excluded from analysis hence the study presents results of 471 participants who had complete data on weight history.

Among the 471 participants assessed, 71.8% were female and 28.2% male. The mean (SD) age of participants was 52 years (13.7). Most participants had stage 2, 3 and 4 cancers at 27.2%, 27.2% and 24.3% respectively. Highest proportion of participants had breast (29.7%) and female genital cancers (22.9%) and lip, oral cavity and pharynx cancers (18.5%) as shown in Table 2.

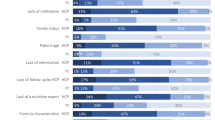

Results showed that more than half (69%) of the participants were well nourished (SGA-A), 19.7% moderately malnourished or had suspected malnutrition (SGA-B) and 11.3% severely malnourished (SGA-C). A mean (SD) PGSGA score of 6.76 (5.17) was reported. When classified based on the type of nutrition intervention, the study indicated that 17.2% of the participants required minimal nutrition intervention with routine assessments and reassurance, 14.2% required constant nutrition education for both the patient and the caregivers, pharmacological intervention based on biochemical analysis, 34.8% required interventions on symptoms management while 33.8% require critical nutrition care as shown in Table 3.

The study results showed a statistically significant difference in the mean PGSGA scores for each of the PGSGA classification of nutrition status (p < 0.001) with the highest proportion (86.8%) of severely malnourished participants having the highest scores. More females (79.4%) than males (20.6%) were well nourished SGA-A, however, the reverse observed with severe malnutrition SGA-C(m;54.7%; f; 45.3%) indicating a statistically significant difference in nutrition status by sex types (P < 0.001). The study also showed a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) in nutrition status and cancer staging with highest proportions (31.5%) of participants with stage 2 cancers being well nourished and most stage 4 cancer participants presenting with moderate and severe malnutrition (SGA-B; 37.5%; SGA-C 29.4%). When ranked based on the cancer types, findings indicated a significant association with the level of malnutrition (p < 0.001). For instance, results revealed that the prevalence of severe malnutrition was highest among participants with digestive organ cancers (49.1%) followed by those with lip cancer (17%) and the least prevalence reported in those with Karposi Sarcoma (0%). Most participants with breast and female genitalia cancers were well nourished SGA-A at 37.2 and 24.2% respectively as shown in Table 4.

Discussions

This study assessed the nutritional status of cancer outpatients receiving treatment at two cancer treatment centers in Nairobi Kenya using scored PGSGA tool. Results revealed that 31% of the patients were undernourished (11.3% severely malnourished and 19.7% moderately malnourished). The findings show a statistically significant difference in nutrition status with more males (54.7%) than females (45.3%) reported to be severely malnourished (p < 0.001). There was a statistically significant (p < 0.001) difference in nutrition status among patients with different cancer stages with more stage 4 patients being moderately and severely malnourished than patients in other stages. A mean(SD) PGSGA Score of 6.79(5.17) was established and this indicated that nearly all patients require symptom management as indicated in the Ottery guidelines [9]. When categorized based on the type of intervention the second highest proportion (33.8%) of participants required critical nutrition care (Score > 9).

Results revealed that 31% of the patients were undernourished (11.3% severely malnourished and 19.7% moderately malnourished). Malnutrition has been known to occur mostly as a comorbidity among cancer patients with an estimated prevalence of 20–80% [2, 3, 13]. Combined effects of the cancer and treatment option often predispose cancer participants to nutrient depletion and inadequate food intake resulting in poor nutritional profiles [14,15,16].

Results from our study were consistent with those from an Australian study which showed that 17% of cancer outpatients were severely malnourished based on an assessment carried out using subjective global assessment [7]. Although showing a slightly lower prevalence, our results were also consistent with findings from a study carried out among elderly cancer patients which showed that 14.6% of participants were severely malnourished [17]. PGSGA is used as an assessment tool that better identifies established malnutrition than nutritional risk [18]. In Kenya, malnutrition remains a challenge among cancer outpatients in Kenya because most of the nutrition interventions are carried out among cancer inpatients [19]. A study carried out among cancer patients established that only 18% of cancer outpatients reported to have received nutrition services [20]. Majority of these patients have limited information on appropriate nutrition practices during cancer treatment and rely on myths and misconceptions that later influence dietary intake resulting to poor nutrition status. As much as Kenya is faced with these challenges compared to the developed world, this study provides opportunities that can be tapped into to improve nutritional outcomes for cancer patients. For instance, there is need to scale up nutrition interventions for cancer outpatients, develop appropriate guidelines for managing side effects of treatment and promoting better practices among cancer patients especially while they are at home. There is also need for appropriate education and counselling for caregivers of these patients to prevent malnutrition.

The findings show a significant difference in nutrition status with more males (54.7%) than females (45.3%) reported to be severely malnourished (p < 0.001). In Kenya, among male cancer patients, majority suffer from prostate, oesophageal and colorectal cancer compared to women who present with breast and cervical cancer [21]. Studies have revealed that digestive organ cancers; Oesophageal, Colorectal and Stomach cancer present a higher risk of malnutrition compared to cancers related to reproductive system [22] hence men in Kenya are more likely to suffer malnutrition compared to women on the basis of cancer type. In addition, men are more likely to experience severe effects from cancer compared to women because of their poor health seeking behaviors; they often seek for medical attention at a later stage when the damage is already done [23]. Moreover, the Kenya Demographic Health Survey indicates that one third (33%) of women in Kenya are overweight and obese with only 9% undernourished [24] hence lower cases of severe malnutrition in women compared to men. Therefore, there is need for nutritionists managing cancer patients to continuously offer nutrition support, nutrition education, counselling and follow up of male cancer patients. There is also need to carry out training, provide information to empower male cancer patients on the role of nutrition therapy in improvement of treatment outcomes.

Our findings show that stage 4 patients were significantly (p < 0.001) moderately and severely malnourished compared to patients in the other stages. Our findings concur with results from a study carried in Korea among hospitalized cancer patients with advanced stages (60.5%) who had a higher prevalence of malnutrition than other patients (p < 0.0001). Similarly, patients with digestive organ and lip cancers had higher levels of under nutrition compared to those with breast and cancers that affect female reproductive organs. Studies have shown that participants with lip/oral cancers report highest levels of malnutrition [16] hence need for timely nutrition intervention among these patients. Most of these patients experience dysphagia hence consume less food especially in cases where enteral or parenteral modes of feeding have not been initiated. In a similar study among 498 participants with advanced GI cancers in Beijing, results identified that 54% required improved nutrition support with PGSGA score of ≥9 [8]. Evidence has shown that the prevalence of malnutrition depends on the type, location, stage of tumor, and type of treatment used [7, 25]. Our findings concur with a study carried out to determine factors influencing nutrition status among cancer patients which indicated that malnutrition is related to type and site of origin of tumor and in early stages of disease is more pronounced in patients with oesophagus and stomach cancer [26]. In addition the same study showed that malnutrition gets more severe as the disease progresses to advanced stages except for breast and cervical cancer [26]. Another study among women with female genital tumors showed no significant difference in nutrition status by PGSGA according to different cancer stages [27]. In settings with limited dieticians as Kenya, provision of systems and guidelines for malnutrition based on the cancer type will be ideal. There is need to promote early diagnosis of malnutrition and create awareness on management of cancer and treatment side effects that lead to undernutrition among cancer patients for effective outcomes.

A PGSGA Score of 6.79 (5.17) in the findings is an indication that nearly all patients require symptom management as indicated in the Ottery guidelines [9]. When categorized based on the type of intervention the second highest proportion (33.8%) of participants require critical nutrition care (Score > 9). A similar study carried out in India among cancer participants showed that 35.7% of participants had PG-SGA score between 4 and 8 hence require intervention by dietitian; 20% had score > 9 hence recommended critical nutritional intervention [3]. The scored PGSGA tool is unique such that it helps identify malnourished hospital participants as well as give guidelines for triaging patients for nutrition intervention. Additionally, the score helps identify impact of symptoms on nutrition status of the participants which in turn impacts on treatment outcomes and prognosis therefore highly recommended for use in decision making on appropriate nutrition care processes for cancer patients [3].

PGSGA tool being subjective, relies heavily on information reported by the patients especially on dietary history and changes in the physiological state of the patients in the past 2 weeks and 1 month. One of the study limitations was the recall bias where some patients could not recall changes in their dietary practices in the past 1 month or past 2 weeks, and in a few circumstances the weight history. In such scenarios, research assistants probed for more and sought clarification from caregivers where necessary. In addition, information on patient’s weight history was extracted from medical records. In cases where the information was missing, reported weight by the patients was used.

Conclusions

Nutrition assessment is necessary for timely nutrition interventions for cancer patients. It also helps to prevent further or pending malnutrition and weight loss during treatment and ultimately improve the quality of life of persons with cancer. As indicated by the results, the PGSGA tool is able to identify cancer patients both at risk of malnutrition and those severely malnourished and also provides a guideline on the type of nutrition intervention. There is therefore a need for adoption of the tool in nutrition management of cancer outpatients in Kenya.

Abbreviations

- CPHR:

-

Centre for Public Health Research

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- KEMRI:

-

Kenya Medical Research Institute

- KNH:

-

Kenyatta National Hospital

- PGSGA:

-

Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SERU:

-

Scientific and Ethics Review Unit

- SGA-A:

-

Subjective Global Assessment Anabolic

- SGA-B:

-

Subjective Global Assessment Between Anabolic and Catabolic

- SGA-C:

-

Subjective Global Assessment Catabolic

- TCC:

-

Texas Cancer Centre

References

Shike M. Nutrition therapy for the cancer patient. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:221–34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8821569. Accessed 4 Oct 2016.

Kumar NB. Nutritional Management of Cancer Treatment Effects; Assessment of Malnutrition and Nutritional Therapy Approaches in Cancer Patients. Springer. 2012. http://www.springer.com/cda/content/document/cda_downloaddocument/9783642272325-c1.pdf?SGWID=0-0-45-1327022-p174274166. Accessed 24 Oct 2016.

Parasa K, Avvaru K. Assessment of nutritional status of cancer patients using scored PG-SGA tool. IOSR J Dent Med Sci Ver I. 2016;15:2279–861. doi:10.9790/0853-1508013740.

Santarpia L, Contaldo F, Pasanisi F. Nutritional screening and early treatment of malnutrition in cancer patients. 2011.

Andreoli A, De Lorenzo A, Cadeddu F, Iacopino L, Grande M. New trends in nutritional status assessment of cancer patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2011;15:469–80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21744742. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

Ottery FD. Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition. 1996;12(1 Suppl):S15–9.

Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M. Use of the scored patient-generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:779–85.

Zhang L, Lu Y, Fang Y. Nutritional status and related factors of patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1239–44. doi:10.1017/S000711451300367X.

FD Ottery. Scored patient-generated subjective global assessment(PGSGA). 2001. http://pt-global.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/09/PG-SGA-Sep-2014-teaching-document-140914.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2017.

Mugenda O. Research methods: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. 1999. http://etd-library.ku.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/123456789/8328/.Mugenda,Olive M..pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y. Accessed 13 June 2017.

Ministry of Health. National Guidelines For Cancer Management Kenya. 2013. http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/National-Cancer-Treatment-Guidelines2.pdf. Accessed 22 Apr 2017.

National Cancer Institute. SEER Training:Staging a Cancer Case. 2015. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/staging/. Accessed 22 Apr 2017.

Isenring E, Bauer J, Capra S. The scored patient-generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA) and its association with quality of life in ambulatory patients receiving radiotherapy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:305–9.

Mendes J, Alves P, Amaral TF. Comparison of nutritional status assessment parameters in predicting length of hospital stay in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2013;33:466–70.

Paccagnella A, Morello M, Da Mosto MC, Baruffi C, Marcon ML, Gava A, et al. Early nutritional intervention improves treatment tolerance and outcomes in head and neck cancer patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:837–45. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0717-0.

Sharma D, Kannan R, Tapkire R, Nath S. Evaluation of nutritional status of cancer patients during treatment by patient-generated subjective global assessment: a hospital-based study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:8173–6. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.18.8173.

Araújo dos Santos C, de Oliveira Barbosa Rosa C, Queiroz Ribeiro A, de Cássia Lanes Ribeiro R. Patient-generated subjective global assessment and classic anthropometry: comparison between the methods in detection of malnutrition among elderly with cancer. Nutr Hosp Nutr Hosp. 2015;3131:384–92.

Barbosa-Silva MCG, Barros AJD. Indications and limitations of the use of subjective global assessment in clinical practice: an update. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9. http://journals.lww.com/co-clinicalnutrition/Fulltext/2006/05000/Indications_and_limitations_of_the_use_of.14.aspx.

Wangari Ndirangu. Cancer patients to benefit from a feeding program | Kenya news agency. 2016. http://kenyanewsagency.go.ke/en/cancer-patients-to-benefit-from-a-feeding-program/. Accessed 26 Apr 2017.

Kaduka L, Opanga Y, Bukaniah Z, Mutisya R, Korir A, Mwangi M, Erastus Muniu CM. Cancer and Nutrition. Nairobi; 2016. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-9561-5.

Korir A, Okerosi N, Parkin DM. Cancer Incidence in Nairobi - Kenya Nairobi Cancer Registry Report 2004 – 2008 Nairobi Cancer Registry - Kemri Quenquennial Report ( 2004-2008 ) Including National Estimates for the Year 2012. 1st edition. Nairobi: Kenya Medical Research Institute; 2014.

Bozzetti F. Nutritional support of the oncology patient. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;87. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.006.

Laura J. Martin MD. Men have higher cancer death rates than women. 2011. http://www.webmd.com/cancer/news/20110712/men-have-higher-cancer-death-rates-than-women. Accessed 23 Apr 2017.

KNBS, KEMRI, NACC M. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Nairobi; 2015. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr308/fr308.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 2017.

Gupta D, Vashi PG, Lammersfeld CA, Braun DP. Role of nutritional status in predicting the length of stay in cancer: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;59:96–106.

Bozzetti F, Migliavacca S, Scotti A, Bonalumi MG, Scarpa D, Baticci F, et al. Impact of cancer, type, site, stage and treatment on the nutritional status of patients. Ann Surg. 1982;196:170–9.

Rodrigues CS, Chaves GV. Patient-generated subjective global assessment in relation to site, stage of the illness, reason for hospital admission, and mortality in patients with gynecological tumors. Support Care Cancer. 2014;23:871–9.

Acknowledgements

The study team appreciates the contribution of various partners who participated in the development, planning and execution of the study. We wish to express our heartfelt appreciation to the experts from Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) who jointly participated in the planning and implementation processes. Our earnest gratitude goes to the management of collaborating institutions and facilities for providing administrative, technical and logistical support. We wish to thank the facility staff; Lydia Wataka and Onesmus Kariuki of Texas Cancer Centre and Irene Karanja and Carol Wambua of KNH for their dedication and support. We also thank the following research assistants for their hard work and commitment to this study: Rodgers Ochieng, Melvin Obuya, Schiller Mbuka, Peter Shigholi, Dorine Njeri, Mercy Rotich and Paul Odacha. Many thanks go to all the study participants from KNH and Texas Cancer Centre for their co-operation. This study would not have been successful without their cooperation. Much appreciation goes to the KEMRI SERU and KNH ERC for providing the necessary guidance and approvals to undertake the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (grant number IRG 176/6).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available at Kenya Medical Research Institute in Kenya but restrictions apply to the availability of these data which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YO Conceptualized the study, protocol development, grant application, study execution, data cleaning, data analysis and manuscript development. LK Conceptualized the study, protocol development, grant application, execution of study, data analysis and manuscript development. ZB Protocol development, data collection coordination, data analysis and manuscript writing. RM Protocol development, data collection, analysis and manuscript writing. EM Development of Study design and methodology, data processing, data analysis and manuscript writing. MM Development of study design and methodology, data processing, data analysis and manuscript writing. VT Data collection and manuscript writing. CM Proposal development, grant application and manuscript development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in line with the guidelines stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the KEMRI Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (Reference number: KEMRI/SERU/CPHR/001/3026) and the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Review Committee (Study Registration Certificate: P462/07/2015). Written informed consent to participate in the study was sought from all the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Opanga, Y., Kaduka, L., Bukania, Z. et al. Nutritional status of cancer outpatients using scored patient generated subjective global assessment in two cancer treatment centers, Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Nutr 3, 63 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-017-0181-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-017-0181-z