Abstract

Background

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) of the liver is a benign disorder. It is usually observed in the skin, orbit, thyroid, lung, breast, or gastrointestinal tract, but rarely in the liver. Since the first report of RLH of the liver in 1981, only 75 cases have been described in the past literature. Herein, we report a case of RLH of the liver in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), which was misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) preoperatively and resected laparoscopically.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old Japanese woman with autoimmune hepatitis was followed up for 5 years. During her medical checkup, a hypoechoic nodule in segment 6 of the liver was detected. The nodule had been gradually increasing in size for 4 years. Abdominal ultrasound (US) revealed a round, hypoechoic nodule, 12 mm in diameter. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated that the nodule was slightly enhanced in the arterial dominant phase, followed by perinodular enhancement in the portal and late phases. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image (T1WI) and slightly high signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (T2WI). The findings of the Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI were similar to those of contrast-enhanced CT. Tumor markers were all within the normal range. The preoperative diagnosis was HCC and a laparoscopic right posterior sectionectomy was performed. Pathological examination revealed that the nodular lesion was infiltrated by small lymphocytes and plasma cells, and germinal centers were present. Immunohistochemistry was positive for B cell and T cell markers, indicating polyclonality. The final diagnosis was RLH of the liver.

Conclusions

The pathogenesis of RLH of the liver remains unknown, and a definitive diagnosis based on imaging findings is extremely difficult. If a small, solitary nodule is found in female patients with AIH, the possibility of RLH of the liver should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH), also called pseudolymphoma or nodular lymphoid lesions, of the liver is a benign disorder. It is characterized by a marked proliferation of non-neoplastic polyclonal lymphocytes forming follicles with active germinal centers. RLH is usually observed in the skin, orbit, thyroid, lung, breast, or gastrointestinal tract, but rarely in the liver. Since the first report of RLH of the liver in 1981 by Snover et al. [1], only 75 cases have been described in the past literature. Etiology and pathogenesis of RLH of the liver is completely unknown.

Herein, we report a case of RLH of the liver in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), which was misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) preoperatively and resected laparoscopically.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old Japanese woman was followed for AIH for 5 years and has been prescribed oral steroids. She had a medical history of cerebral hemorrhage. During her medical checkup, a hypoechoic nodule in segment 6 (S6) of the liver was detected by abdominal ultrasound (US). It was initially diagnosed as a simple cyst. The nodule gradually increased from 7 mm to 12 mm in diameter over a 4-year period. On physical examination, there were no abnormalities. A laboratory examination showed no remarkable abnormalities: aspartate aminotransferase 19 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 19 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 168 U/L, γ-glutamyltransferase 11 U/L, total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dl, albumin 3.90 g/dl, platelet counts 32.1 × 104/μl, and prothrombin time 113%. Serum IgG level was 2566 mg/dl. Tumor markers were within normal range: α-fetoprotein 1.2 ng/ml, protein-induced vitamin K absence-II 16.0 mAU/ml, carcinoembryonic antigen 0.3 ng/ml, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 8.1 U/ml. Hepatitis virus markers were all negative.

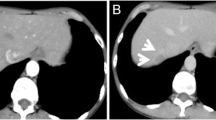

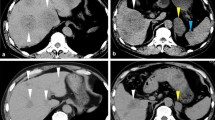

Abdominal US revealed a round hypoechoic homogeneous nodule, 12 mm in diameter (Fig. 1). It was enhanced in the arterial dominant phase followed by defected in the post vascular phase by the contrast medium. Plain computed tomography (CT) showed low density in S6 of the liver and contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated that the nodule was slightly enhanced in the arterial dominant phase followed by perinodular enhancement in the portal and late phases (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image (T1WI) and slightly high signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (T2WI). On the diffusion-weighted image (DWI), the lesion showed high signal intensity. Gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethlenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA)-enhanced MRI showed similar findings as contrast-enhanced CT and subsequently presented the defect in the hepatobiliary phase (Fig. 3).

MRI demonstrates that the nodule shows well-defined low signal intensity in T1-weighted image (a), slightly high signal intensity in T2-weighted image (b), and strongly high signal intensity in diffusion-weighted image (c). Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI reveals that the nodule is slightly enhanced in the arterial phase (d). The lesion shows perinodular enhancement in the portal phase (e) and a defect in hepatobiliary phase (f) (white arrowhead)

The preoperative diagnosis was HCC. Because there was a risk of intraabdominal seeding, we did not perform percutaneous needle biopsy of the nodule. The patient received laparoscopic right posterior sectionectomy. The cut section of the resected liver showed a well-demarcated, round, yellowish-white lesion measuring about 14 mm.

Pathological examination revealed a nodular lesion without fibrous capsule. The lesion was infiltrated by small lymphocytes and plasma cells, and germinal centers were present (Fig. 4a). Marked lymphoid cell infiltration was found in the portal tracts around the nodule (Fig. 4b). Although many small granulomas were found in the lesion, infectious pathogens were not found on periodic acid-Schiff, Gomori-Grocott, or Ziehl-Neelsen stainings. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the follicles were CD20-positive. The lymphocytes in the germinal centers were CD10-positive and Bcl-2-negative. The interfollicular area was composed of CD3-positive small T cells. Infiltrating plasma cells showed a polyclonal expression of cellular immunoglobulin kappa and lambda chains (Fig. 5). Some IgG4-positive plasma cells were present, but most were IgG-positive plasma cells. The final diagnosis was RLH of the liver.

Immunohistochemical staining reveals that the follicles are CD20-positive. The lymphocytes in the germinal centers are CD10-positive and Bcl-2-negative. The interfollicular area is composed of CD3-positive small T cells. Infiltrating plasma cells show a polyclonal expression of cellular immunoglobulin kappa and lambda chains

The post-operative course was uneventful and she was discharged on post-operative day nine.

Discussion

RLH of the liver is rare. Based on a review of the PubMed database from 1981 to 2019 using the keywords “Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia,” “Pseudolymphoma,” and “Liver,” we found 75 cases of RLH of the liver [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. These cases, along with our case, are summarized in Table 1. Of the 76 cases, 71 (93.4%) were female. The average patients’ age was 56.7 years old (range, 15–85). Among them, 35.5% had liver diseases, 17.1% had autoimmune disease, and 27.6% had a malignant tumor. Many were solitary (84.7%), the average size being 16.3 mm (range, 4–105 mm) and 81.3% of the tumors were less than 20 mm in diameter. Many were located in the right lobe (62.9%). 93.1% were diagnosed as malignant tumors such as HCC, cholangiocellular carcinoma (CCC), or metastatic. Surgical resection was performed in 82.9% of cases. US findings showed most of the lesions were round and hypoechoic. Plain CT revealed low density and findings on contrast-enhanced CT ranged from enhanced to slightly enhanced to perinodular enhancement. On MRI, almost all lesions were found to have low intensity on T1WI and high intensity on T2WI and presented various enhancement patterns similar to the CT findings.

Etiology and pathogenesis of RLH of the liver is not fully understood. Many patients with RLH of the liver have liver disease, autoimmune disease, or a malignant tumor. It is speculated that RLH is related to a reactive immunological response to a chronic inflammatory process. Nakabayashi et al. reported that tumor growth factor-β knockout mice showed multiple lymphoproliferative disorders similar to those observed in the pseudolymphoma of Sjögren’s syndrome, and that upregulation of several inflammatory cytokine genes, interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and IL-10, was observed in their salivary glands [52]. Up/downregulation of some cytokines and chemokines are strongly associated with cancer growth and progression [53]. Many cases of RLH of the liver have a history of malignant tumors; cytokines and chemokines derived from the malignant tumors may affect the occurrence of RLH.

The imaging findings of RLH are nonspecific and varied from strongly enhanced, slightly enhanced, to perinodularly enhanced on contrast CT and MRI. Thus, it is extremely difficult to differentiate hepatic RLH from malignant tumors such as HCC and CCC and metastatic tumors based on imaging findings alone. Indeed, surgical resections were performed for the diagnosis of these malignancies in many cases. The nodule increased in size in some cases, including ours [8, 34, 48], but in other cases, it reduced without any treatment [14, 27]. Additionally, malignant conversion has been reported in the lungs, stomach, and skin [54,55,56]. In RLH of the liver, only one case transformed into mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [57]. Therefore, we think that pathological diagnosis by needle biopsy and intensive follow-up is warranted.

Histologically, RLH of the liver consists of hyperplastic lymphoid follicles, lymphocytes, and other inflammatory cells. Immunohistochemical staining is positive for B cell markers (CD20 or CD79α) and T cell markers (CD3 or CD4), indicating polyclonality. CD20-positive B cells are predominantly located in the lymphoid follicles and CD3-positive T cells are predominantly located in interfollicular areas. Additionally, the lymphocytes in the germinal centers are negative for Bcl-2, which indicates the non-neoplastic and reactive nature [30]. Some reported that portal venular disappearance and/or stenosis, caused by marked lymphoid cell infiltration in the portal tracts around nodules, was observed in the perinodular lesion [22, 27, 31, 57, 58]. These pathological changes may induce portal flow disturbances and increased hepatic arterial flow in the perinodular lesion, resulting in perinodular enhancement. A similar finding was found in the present case.

In a meta-analysis [59], the pooled HCC incidence rate in AIH patients without cirrhosis was 1.14 per 1000 person-years and 10.07 per 1000 person-years in AIH patients with cirrhosis, which was lower than viral hepatitis such as hepatitis B or C. When a nodule is detected in a patient with AIH, we should consider the possibility of RLH of the liver.

Conclusions

We presented a case of RLH of the liver associated with AIH and performed a sectionectomy with the presumptive diagnosis of HCC. However, the lesion was found to be a benign RLH upon pathological and histochemical examination of the resected specimen. The pathogenesis of RLH of the liver remains unknown, and a definitive diagnosis based on imaging findings is extremely difficult. If a small, solitary nodule is found in female patients with AIH, the possibility of RLH of the liver should be considered.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- AIH:

-

Autoimmune hepatitis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted image

- Gd-EOB-DTPA:

-

Gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethlentriamine pentaacetic acid

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RLH:

-

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia

- T1WI:

-

T1-weighted image

- T2WI:

-

T2-weighted image

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

References

Snover DC, Filipovich AH, Dehner LP, Krivit W. ‘Pseudolymphoma’. A case associated with primary immunodeficiency disease and polyglandular failure syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1981;105(1):46–9.

Grouls V. Pseudolymphoma (inflammatory pseudotumor) of the liver. Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1987;133(6):565–8.

Isobe H, Sakamoto S, Sakai H, Masumoto A, Sonoda T, Adachi E, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16(3):240–4.

Ohtsu T, Sasaki Y, Tanizaki H, Kawano N, Ryu M, Satake M, et al. Development of pseudolymphoma of liver following interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Intern Med. 1994;33(1):18–22.

Katayanagi K, Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Ueno T. A case of pseudolymphoma of the liver. Pathol Int. 1994;44(9):704–11.

Tanizawa T, Eishi Y, Kamiyama R, Nakahara M, Abo Y, Sumita T, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver characterized by an angiofollicular pattern mimicking Castleman’s disease. Pathol Int. 1996;46(10):782–6.

Kim SR, Hayashi Y, Kang KB, Soe CG, Kim JH, Yang MK, et al. A case of pseudolymphoma of the liver with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1997;26(1):209–14.

Nagano K, Fukuda Y, Nakano I, Katano Y, Toyoda H, Nonami T, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of liver coexisting with chronic thyroiditis: radiographical characteristics of the disorder. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14(2):163–7.

Sato S, Masuda T, Oikawa H, Satoh T, Suzuki Y, Takikawa Y, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(6):1669–73.

Sharifi S, Murphy M, Loda M, Pinkus GS, Khettry U. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver: an immune-mediated disorder mimicking low-grade malignant lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(3):302–8.

Okubo H, Maekawa H, Ogawa K, Wada R, Sekigawa I, Iida N, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver associated with Sjogren’s syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30(2):117–9.

Pantanowitz L, Saldinger PF, Kadin ME. Pathologic quiz case: hepatic mass in a patient with renal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125(4):577–8.

Willenbrock K, Kriener S, Oeschger S, Hansmann ML. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver with simultaneous focal nodular hyperplasia and hemangioma: discrimination from primary hepatic MALT-type non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;448(2):223–7.

Ota H, Isoda N, Sunada F, Kita H, Higashisawa T, Ono K, et al. A case of hepatic pseudolymphoma observed without surgical intervention. Hepatol Res. 2006;35(4):296–301.

Sato K, Ueda Y, Yokoi M, Hayashi K, Kosaka T, Katsuda S. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with multiple carcinomas: a case report and brief review. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(9):990–2.

Takahashi H, Sawai H, Matsuo Y, Funahashi H, Satoh M, Okada Y, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with colon cancer: report of two cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:25.

Maehara N, Chijiiwa K, Makino I, Ohuchida J, Kai M, Kondo K, et al. Segmentectomy for reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36(11):1019–23.

Machida T, Takahashi T, Itoh T, Hirayama M, Morita T, Horita S. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(40):5403–7.

Matsumoto N, Ogawa M, Kawabata M, Tohne R, Hiroi Y, Furuta T, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: sonographic findings and review of the literature. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35(5):284–8.

Jimenez R, Beguiristain A, Ruiz-Montesinos I, Villar F, Medrano MA, Garnateo F, et al. Image of the month. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Arch Surg. 2008;143(8):805–6.

Lin E. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver identified by FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(6):419–20.

Park HS, Jang KY, Kim YK, Cho BH, Moon WS. Histiocyte-rich reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: unusual morphologic features. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(1):156–60.

Okada T, Mibayashi H, Hasatani K, Hayashi Y, Tsuji S, Kaneko Y, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(36):4587–92.

Fukuo Y, Shibuya T, Fukumura Y, Mizui T, Sai JK, Nagahara A, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16(7):CS81–6.

Ishida M, Nakahara T, Mochizuki Y, Tsujikawa T, Andoh A, Saito Y, et al. Hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2010;2(10):387–91.

Sibulesky L, Satyanarayana R, Menke D, Nguyen JH. Reactive nodular hyperplasia mimicking malignant lymphoma in donor liver allograft. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(5):1970–2.

Zen Y, Fujii T, Nakanuma Y. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: a clinicopathological study of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(2):244–50.

Yoshikawa K, Konisi M, Kinoshita T, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Kato Y, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: literature review and 3 case reports. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58(109):1349–53.

Osame A, Fujimitsu R, Ida M, Majima S, Takeshita M, Yoshimitsu K. Multinodular pseudolymphoma of the liver: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Jpn J Radiol. 2011;29(7):524–7.

Marchetti C, Manci N, Di Maurizio M, Di Tucci C, Burratti M, Iuliano M, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of liver mimicking late ovarian cancer recurrence: case report and literature review. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16(6):714–7.

Kobayashi A, Oda T, Fukunaga K, Sasaki R, Minami M, Ohkohchi N. MR imaging of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(7):1282–5.

Hayashi M, Yonetani N, Hirokawa F, Asakuma M, Miyaji K, Takeshita A, et al. An operative case of hepatic pseudolymphoma difficult to differentiate from primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:3.

Amer A, Mafeld S, Saeed D, Al-Jundi W, Haugk B, Charnley R, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver and pancreas. A report of two cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36(4):e71–80.

Yuan L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Cong W, Wu M. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a clinicopathological study of 7 cases. HPB Surg. 2012;2012:357694.

Moon WS, Choi KH. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19(1):87–91.

Taguchi K, Kuroda S, Kobayashi T, Tashiro H, Ishiyama K, Ide K, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1(1):107.

Sonomura T, Anami S, Takeuchi T, Nakai M, Sahara S, Tanihata H, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: perinodular enhancement on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(21):6759–63.

Song KD, Jeong WK. Benign nodules mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma on gadoxetic acid-enhanced liver MRI. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21(2):187–91.

Calvo J, Carbonell N, Scatton O, Marzac C, Ganne-Carrie N, Wendum D. Hepatic nodular lymphoid lesion with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a report of two cases. Virchows Arch. 2015;467(5):613–7.

Lv A, Liu W, Qian HG, Leng JH, Hao CY. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: incidental finding of two cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(5):5863–9.

Kwon YK, Jha RC, Etesami K, Fishbein TM, Ozdemirli M, Desai CS. Pseudolymphoma (reactive lymphoid hyperplasia) of the liver: a clinical challenge. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(26):2696–702.

Higashi T, Hashimoto D, Hayashi H, Nitta H, Chikamoto A, Beppu T, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver requires differential diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1(1):31.

Suzumura K, Hatano E, Okada T, Asano Y, Uyama N, Hai S, et al. Hepatic pseudolymphoma with fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10(3):826–35.

Caputo D, Cartillone M, Coppola R. All that glitters are not gold! Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia mimicking colorectal liver metastases: description of a case and literature review. Updates Surg. 2017;69(1):113–5.

Yang CT, Liu KL, Lin MC, Yuan RH. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: report of a case and review of the literature. Asian J Surg. 2017;40(1):74–80.

Kunimoto H, Morihara D, Nakane SI, Tanaka T, Yokoyama K, Anan A, et al. Hepatic pseudolymphoma with an occult hepatitis B virus infection. Intern Med. 2018;57(2):223–30.

Seitter S, Goodman ZD, Friedman TM, Shaver TR, Younan G. Intrahepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Surg. 2018;2018:9264251.

Takahashi Y, Seki H, Sekino Y. Pseudolymphoma with atrophic parenchyma of the liver: report of a case. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018;49:136–9.

Zhong X, Dong A, Dong H, Wang Y. FDG PET/CT in 2 cases of hepatic pseudolymphoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43(5):e166–e9.

Inoue M, Tanemura M, Yuba T, Miyamoto T, Yamaguchi M, Irei T, et al. A case of hepatic pseudolymphoma in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(10):1863–9.

Zhang W, Zheng S. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(30):e16491.

Nakabayashi T, Letterio JJ, Geiser AG, Kong L, Ogawa N, Zhao W, et al. Up-regulation of cytokine mRNA, adhesion molecule proteins, and MHC class II proteins in salivary glands of TGF-beta1 knockout mice: MHC class II is a factor in the pathogenesis of TGF-beta1 knockout mice. J Immunol. 1997;158(11):5527–35.

Rollins BJ. Inflammatory chemokines in cancer growth and progression. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(6):760–7.

Kulow BF, Cualing H, Steele P, VanHorn J, Breneman JC, Mutasim DF, et al. Progression of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma to cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6(6):519–28.

Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Nichols PW, Wehunt WD, Lazarus AA. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and pseudolymphoma of lung: a study of 161 patients. Hum Pathol. 1983;14(12):1024–38.

Brooks JJ, Enterline HT. Gastric pseudolymphoma. Its three subtypes and relation to lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;51(3):476–86.

Zhou Y, Wang XL, Xu C, Zhou GF, Zeng MS, Xu PJ. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: imaging features on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging. Abdom Radiol. 2028;43:2288–94.

Yoshida K, Kobayashi S, Matsui O, Gabata T, Sanada J, Koda W, et al. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: imaging-pathologic correlation with special reference to hemodynamic analysis. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:1277–85.

Tansel A, Katz LH, El-Serag HB, Thrift AP, Parepally M, Shakhatreh MH, et al. Incidence and determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma in autoimmune hepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1207–17.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing (Figure S1).

Funding

The authors declare that this work was not supported by any grants or funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK drafted the manuscript. KO supervised the study. HS, TH, SK, RM, SF, YN, YG, TS, MY, and RK performed perioperative management of the patient. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Kurume University (No. 2019-082).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanno, H., Sakai, H., Hisaka, T. et al. A case of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. surg case rep 6, 90 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00856-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00856-3