Abstract

Aim

The current study investigates the effect of immediate temporization on the pink esthetics of delayed implants in patients with thin gingival phenotype in combination with a De-epithelialized Free Gingival Graft in the maxillary premolar area.

Methodology

The study population was randomly assigned into two groups. The two groups were treated with delayed implants with simultaneous placement of a de-epithelialized free gingiva graft. The test group was immediately temporized while the control group had no temporization. The pink esthetic score was assessed as the primary outcome. Additional secondary outcomes were assessed such as the keratinized tissue width and the soft tissue thickness.

Results

Twenty implants were placed in the current study, split into 10 implants per group. The results showed that the Pink Esthetic Score of the IT group was 11.88 ± (1.13) and 11.33 ± (1.25) for the CTG group, which showed no statistical difference between the groups after 1 year of follow-up. There was also no significant difference between the two groups at 12 months regarding the keratinized tissue width and the soft tissue thickness.

Conclusions

Immediate and delayed temporizations have no effect on the Pink Esthetics of the delayed implants; however, immediate temporization allowed earlier provisional crown delivery. Soft tissue augmentation of the thin gingival phenotype improved esthetics for both groups.

Trial registration Name of the registry: clinicaltrials.gov; trial registration number: NCT03792425. Date of registration: January 3, 2019. URL of trial registry record: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03792425?term=NCT03792425&draw=2&rank=1

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Main text

Implant dentistry has become an integral part of modern dentistry, and its success is no longer determined merely by osseointegration. Several factors have a pivotal role in the success of implants; among them, is the stability of the peri-implant soft tissues that maintain function and esthetics [1, 2].

Long-term peri-implant soft tissue stability is affected by the peri-implant phenotype [3,4,5]. A gingival thickness of ≥ 2 mm is defined as a thick phenotype capable of withstanding mastication’s daily wear and tear [6]. In contrast, a gingival thickness of < 1.5 mm is defined as a thin phenotype predisposing the tissues to attachment loss [7]. Patients with a thin peri-implant mucosal phenotype are at a higher risk of suffering marginal recessions or the appearance of the metallic shadow of the implant [8, 9]. Therefore, augmentation of the peri-implant mucosa in such cases is recommended to ensure an adequate quantity and quality of the peri-implant soft tissues [10, 11].

Soft tissue augmentation procedures are designed to increase the thickness of the buccal peri-implant mucosa, resist recession and crestal bone resorption, and provide superior esthetics and long-term health [12]. Besides improving the phenotype, augmenting the soft tissues is also recommended from an esthetic point of view to compensate for the volume loss after tooth extraction [13]. Various materials have been used to perform soft tissue grafting around dental implants. Nevertheless, the connective tissue graft remains the gold standard providing the most predictable results [14, 15], specifically the de-epithelialized free gingival grafts (FGG). This technique provides a firmer and more uniform subepithelial connective tissue graft [16,17,18,19]. Beyond augmenting the peri-implant mucosa, immediate temporization has been increasingly utilized in implant placement procedures. This treatment modality serves to mold the peri-implant mucosa and improves the esthetic outcome by optimizing the restoration’s emergence profile. Minor defects can also be treated with proper molding of the peri-implant tissues during the initial healing phase to obtain adequate tissues before final restoration fabrication [20]. Immediate temporization with simultaneous application of the subepithelial connective tissue graft with immediate implants has been widely employed for esthetics and function [13, 14, 19, 21,22,23,24,25].

The current study aims to evaluate the peri-implant soft tissue esthetics following immediate temporization with delayed implant placement and connective tissue grafting in patients with a thin gingival phenotype compared to conventional loading in the maxillary premolar zone.

The outcomes assessed are the Pink Esthetic Score (PES), gingival thickness, and keratinized tissue width.

Materials and methods

Study design and registration

The current study was designed as a randomized, controlled, parallel-group clinical trial, following the CONSORT guidelines. The Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, Cairo University (January 2019) approved the study protocol, and it was registered in the Clinical Trials Registry (clinicalTrials.gov) NCT03792425.

Sample size determination

A sample size of 20 implants was calculated for the current study, with 10 implants in each group. This number was based on a study by Weisner et al. [26], where the reported pink esthetic scores were 11.32 ± 1.63. Based on a null hypothesis and a power of 0.85, 8 subjects in each group were found sufficient to reject the hypothesis. This number was increased to 10 in each group to compensate for the losses during follow-up. The sample size was calculated by the G*Power program (University of Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany).

Eligibility criteria

All patients included in the study were selected from the outpatient clinic of the Department of Oral Medicine and Periodontology—at Cairo University. Patients included in the study had to have a missing maxillary premolar surrounded by sound neighboring teeth, a thin gingival phenotype ≤ 1.5 mm, and adequate ridge dimensions to receive a regular implant. Medically compromised patients, smokers, and pregnant females were excluded from the study.

A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) was taken to determine eligibility for the study to evaluate the Bucco-palatal bone dimensions, including width, height, and density. These measurements were used to determine the appropriate implant length and diameter.

Randomization

Once the patients were enrolled in the study and informed consent was signed, all patients were randomized using computer-generated randomization (www.randomizer.org) in a 1:1 ratio. The allocation sequence was generated by (S.H) who was not involved in the study. The randomized sequence was placed in opaque, sealed, and sequentially numbered envelopes and broken on the day of the surgery. Patients were randomly allocated into either the control group (delayed implant placement with connective tissue graft only) CTG or the intervention group (delayed implant placement with connective tissue graft and immediate temporization) ITG.

Pre-operative phase

A thorough pre-operative assessment of all study subjects was carried out to include medical history, dental history and intraoral clinical examination.

Pre-operative measurements were taken, including the soft tissue phenotype and the width of keratinized gingiva. The gingival phenotype was examined by transgingival piercing using a needle and an endodontic stopper [60]. After giving local infiltration anesthesia [26], the measurements were taken at 3 different points; 2 mm, 4 mm, and 6 mm from the crest of the bone [27].

The width of keratinized gingiva was measured at the mid-buccal area by a periodontal probeFootnote 1 from the gingival margin to the mucogingival junction.

An impression was taken for all eligible patients to create a study cast, which was used to fabricate a vacuum stent to be used postoperatively to protect the palate’s de-epithelialized connective tissue donor site.

Surgical and prosthetic procedures

Following the administration of local anesthesia,Footnote 2 a crestal incision was created using a 15c scalpel [2], and a full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was raised with minimal reflection to expose the crest of the bone [28]. A buccal pouch was then created by extending the reflection in an apical direction to accommodate the connective tissue graft [29]. Sequential drilling was then done following the manufacturer’sFootnote 3 instructions to allow implant placement. The implant was leveled to the alveolar bone crest, and primary stability was achieved [30].

Once the implant was in place, a free gingival graft was harvested and de-epithelialized extra-orally [31] to produce a connective tissue graft of about 1.5 mm in thickness [26]. The CT graft was tucked into the pouch and sutured to the buccal flap with a resorbable sutureFootnote 4 [32]. The graft dimensions were determined based on the dimensions of the edentulous site. Gel foam was placed in the donor site and sutured in place then the stent was fixed in place [26].

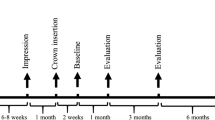

In the IT group (Fig. 1), an open tray impression was taken after implant placement but before graft fixation to avoid damaging the graft. A healing collar was placed over the implant and the surgical site was closed with interrupted sutures. A PMMA temporary crown was fabricated on a temporary abutment and delivered to the patient within 48 h of the surgery. The temporary crown was placed out of occlusion for 3 months [2]. Immediate non-functional loading was only done if adequate primary stability ≥ 25 Ncm was obtained.

In the CTG group (Fig. 2), the flap was sutured with interrupted sutures [26] and left to heal. Implant exposure was done 3 months later by creating a T incision [33], and then a healing collar was placed for about 2 weeks to allow soft tissue molding and maturation.

Postoperative medications included anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs; Ibuprofen 600 mg three times daily for 3 days, and antiseptic mouth rinse (0.2% Chlorhexidine oral rinse) prescribed two times a day for 2 weeks [2]. Patients were instructed to refrain from hard brushing and trauma to the surgical site for 1 week.

All final impressions were taken indirectly, using an open tray technique, and the final CAD-CAM zirconia crowns were fabricated for all the study subjects [26]. Both groups received their final zirconium crown 3 months after implant placement.

Follow-up visits were done at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after implantation. Digital pictures were taken for the PES evaluation, and gingival thickness and keratinized tissue width measurements were recorded at the follow-up visits.

Calibration

Blinding of the patients and the operator was not possible, but the outcome assessors and the statistician were blinded.

Pink Esthetic Score (PES)

Examiners applied the PES index used by Fürhauser [34] to assess the soft tissue around the implant. The PES was evaluated 4 times: 3 months post-implant insertion, after 6 months, 9 months, and at 12 months postoperatively. Every crown was photographed with a digital cameraFootnote 5 with the reference tooth completely visible to ensure comparability.

The esthetic evaluations of the soft tissue PES were evaluated by two assessors (M.T) and (R.W) who were not part of the treatment procedures. The assessors were calibrated before the study on 20 single implant cases, then after 1 week, asked to reexamine the same cases in a different order. The frontal color pictures were re-scored twice with an interval of 1 week. Furthermore, the intra-examiner reproducibility was evaluated.

Gingival thickness

Gingival thickness was measured by piercing the gingiva along the long axis of the implant at 3 different points at 2 mm, 4 mm, and 6 mm below the center of the crest of the ridge into the mucosa until it contacts the cortical bone [26, 27, 60]. Postoperatively, readings were taken at 4-time points: 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Keratinized tissue width

It was measured by a periodontal probe (see Footnote 1) from the gingival margin to the mucogingival junction in the mid-buccal area. Postoperatively, readings were taken at 4-time points: 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data are reported as mean and standard deviation, and nominal data are reported as frequency. Nominal data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Numerical data were explored for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Shapiro–Wilk test. In the case of normally distributed numerical variables, both groups were compared with an independent t-test. In contrast, for non-normally distributed variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was a more appropriate choice. For intragroup analysis in normally distributed data, repeated measure ANOVA was utilized. In case it reported a statistical significance, post hoc multiple comparisons were made with Bonferroni adjustments. For non-normally distributed data, intragroup comparisons were performed using the Friedman test. In case it was statistically significant, the post-hoc Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was applied for pairwise comparisons. All tests were two-tailed, and P-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS advanced statistics (Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 26, BM Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Demographic data (Table 1)

In the current study, all participants were females, with an average age range of 34 years in the IT group and 36.11 years in the CTG group. The osseointegrated implants were distributed among the sites as follows 3 implants in the first premolar region and 6 implants in the second premolar region in the intervention group; 6 of them were of diameter 3.5 mm and 3 implants were 4 mm, whereas in the control group; 4 implants were placed in the first premolar region and 5 in the second premolar region; 7 of them were of 3.5 mm diameter while 2 of them were 4 mm with no significance in the distribution between the two groups p = 0.637.

Implant survival

Within the twenty patients enrolled in the study, randomly assigned as ten participants in each group, no participants were lost to follow-up. Two implants out of 20 had early failure; one was in the intervention group (survival rate of 90%), and one was in the control group (survival rate of 90%).

Pink Esthetic score (Table 2)

Since two blinded examiners assessed the PES, intra-examiner reproducibility was evaluated resulting in a reliability of 0.826 (95% CI 0.728–0.891) while the correlation coefficient between the 2 examiners reached (ICC) = 0.85.

PES intergroup assessment was calculated using the independent t-test, while intragroup measurements were assessed using repeated measure ANOVA showing no significant difference between the two groups.

PES at 12 months (Table 3)

On reviewing the individual elements of the Pink Esthetic Score for each group.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Discussion

Esthetics is now considered a mandatory factor in assessing implant success and must be considered a priority and a goal side to side with osseointegration [1, 14, 32, 35]. Our study aimed to assess whether immediate temporization with a de-epithelialized subepithelial connective tissue graft in delayed implant placement would enhance the pink esthetics in patients with a thin gingival biotype. The current study aimed to close the knowledge gap highlighted in a review article by Atieh [19], where it was noted that the effect of the gingival phenotype and width of the keratinized tissue were not clearly discussed in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing immediate temporization to conventional loading with de-epithelialized free gingival graft in patients with a thin gingival phenotype in delayed implants [44,45,46].

Immediate temporization allows the shortening of the healing period and early optimization of the esthetics. It also has a pivotal effect on the shaping of the peri-implant soft tissues, papilla fill, and producing the proper emergence profile for single-tooth implant restorations [2, 24, 41,42,43]. Combining the effect of immediate temporization with simultaneous soft tissue grafting is advantageous to the healing process compared to delayed temporization that require a second surgery for implant exposure. Performing multiple surgical procedures in a single site is associated with shrinkage as the wound edges get drawn together [39, 40]. This shrinkage occurs as a proportion of the fibroblasts begin to mature into a phenotype that resembles the smooth muscle cells [38] leading to pronounced shrinkage. Even when considering soft tissue grafting, it is known that subepithelial connective tissue grafts are associated with shrinkage (25–45%) that occurs within the first month but could be detected up to 1 year [36, 37].

Patients with thin gingival phenotypes are at a higher risk of esthetic complications in the long term. The appearance of a greyish shadow of the implant, midfacial peri-implant mucosal recession, incomplete papilla fill, and decreased soft tissue stability are among those esthetic complications [8, 47,48,49,50], so the gingival thickness is considered a key factor in achieving the ideal esthetic outcome. Crestal bone stability has been linked to the thicker phenotype [48, 51, 52], as the sites with thick gingival phenotypes are less prone to buccal changes compared to thin gingival biotypes. Adequate amount of tissues is needed to curb the crestal bone loss and achieve the biological width of the peri-implant mucosa or the supra crestal tissue height [48, 51, 52]. Therefore, augmentation is beneficial in patients with a thin gingival phenotype receiving an implant in the esthetic zone to ensure better thick peri-implant mucosal tissues.

The present study’s primary outcome was the pink esthetic score as it could objectively assess esthetics [14, 34, 53]. Two different blinded examiners (M.T, R.W.) recorded the readings due to the subjective nature of the PES outcome, and an average between the two scores was calculated (Table 2). The CTG group yielded a score of 11.33 ± 1.25 at 1-year follow-up. This agreed with findings reported by [26], who reported a PES of 11.32 ± 1.63 after 1 year. Bruyckere et al. [54], demonstrated in an RCT utilizing connective tissue graft to re-establish buccal convexity, the PES of the CTG graft group after a 1-year follow-up was 10.48 ± 2.25.

There was no statistical difference between the IT and CTG groups after 1 year as they showed 11.88 ± 1.13 and 11.33 ± 1.25, respectively. The IT group did not result in better PES. Nevertheless, it allowed the patient to have a provisional crown at an earlier stage, therefore, saving the treatment time. The esthetics of single delayed implant placement in a thin phenotype represents a challenge to clinicians. The current study shows that subepithelial connective tissue grafting with or without temporization could produce excellent esthetics’ results.

The detailed PES did not show a significant difference in the various comparison aspects. Furthermore, both groups showed excellent alveolar process readings, attributed to the connective tissue grafting. This compensates for the volume loss that occurs due to buccal bone resorption after extraction, which is a common defect in delayed implants. Occlusal photos could have given more insights into the alveolar process improvement. It appears that achieving excellent PES is related to soft tissue augmentation rather than the timing of temporization. The changes in peri-implant mucosal soft tissue thickness were evaluated at levels 2, 4, and 6 mm from the mucosal margin of the future restoration (Table 4). Measurements at different levels were performed by [27, 55]. This was adopted in the present study to give a complete picture of changes in the peri-implant mucosa, especially since volumetric changes were not performed. The changes reported in both intervention and control groups (Table 4) showed that maximum gain was achieved within 3 months, and then there was a minor reduction in soft tissue thickness. Similar findings have been reported by [19, 56, 57], and could be attributed to soft tissue grafts undergoing remodeling processes that may start from 1 to 6 months after soft tissue augmentation, according to [13]. These results are in line with the results of [55, 56] who reported a comparable increase in mucosal thickness.

The results of our CTG group are slightly inferior to those [26], which might be because the study did not consider the gingival phenotype.

In the literature, the studies that evaluated changes in mucosal thickness after concurrent application of C.T graft and immediate temporization were mainly related to immediate implant placement [58]. The palatal positioning of the implants and the concave contoured immediate provisional crowns at the subgingival level creates an internal void between the gingiva and the immediate provisional restoration, which leads to the thickening of the soft tissue thickness in the IT group even without a connective tissue graft [17].

Regarding the keratinized tissue width, there was no significant difference between the two groups, 4.88 ± 0.23 and 4.61 ± 0.42 at 12 months follow-up. Yet, there was a significant intragroup change through time from the baseline values of 4.13 ± 0.23 and 3.94 ± 0.58 for the test and the control groups, respectively (Table 5).

In the control group, there was a significant increase in KTW from 3.94 ± 0.58 to 4.56 ± 0.39 mm after 6 months. This agrees with [35, 59], which yielded a significant mean KT increase at 1-year follow-up after soft tissue augmentation.

When interpreting the results of the current study, some limitations should be acknowledged. Although favorable results were achieved in this short-term follow-up, larger-scale clinical studies with longer follow-ups are needed to demonstrate good external validity and adequately evaluate the long-term efficacy of such treatment approaches. Furthermore, further research with radiographic tools should be explored to determine labial bone changes, with the peri-implant soft tissue thickness. Finally, all the patients were females, and the missing tooth was located in the premolar area, which could affect the outcomes.

Conclusion

Augmentation of the soft tissues with connective tissue graft in patients with a thin gingival phenotype produced particularly good esthetics in terms of PES scores with continuous improvement in PES in both groups after permanent restoration up to 12 months. Immediate temporization seemed to improve the overall treatment outcome.

Recommendations

RCTs with longer follow-up periods, and larger sample sizes are needed to evaluate the benefit of immediate temporization with delayed implant placement and simultaneous connective tissue grafting.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

UNC—15 Hu friedy.

Articaine hydrochloride 4% with 1:100,000 Epinephrine.

IS II active, Neobiotech, South Korea.

Vicryl Assut suture 5/0.

Canon EOS 80 D.

References

Bichacho N, Van Dooren E, Fradeani M, Talmor G. Tissue management and prosthetic considerations with immediate implantation in the anterior maxilla. Berlin: Quintessence; 2012. p. 105–20.

Donos N, Horvath A, Mezzomo LA, Dedi D, Calciolari E, Mardas N. The role of immediate provisional restorations on implants with a hydrophilic surface: a randomised, single-blind controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(1):55–66.

Mazzotti C, Stefanini M, Felice P, Bentivogli V, Mounssif I, Zucchelli G. Soft-tissue dehiscence coverage at peri-implant sites. Periodontol 2000. 2018;77(1):256–72.

Gamborena I, Avila-Ortiz G. Peri-implant marginal mucosa defects: classification and clinical management. J Periodontol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.20-0519.

Linkevicius T, Puisys A, Svediene O, Linkevicius R, Linkeviciene L. Radiological comparison of laser-microtextured and platform-switched implants in thin mucosal biotype. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015;26(5):599–605.

Souza AB, Tormena M, Matarazzo F, Araújo MG. The influence of peri-implant keratinized mucosa on brushing discomfort and peri-implant tissue health. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(6):650–5.

Claffey N, Shanley D. Relationship of gingival thickness and bleeding to loss of probing attachment in shallow sites following nonsurgical periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13(7):654–7.

Kan JYK, Rungcharassaeng MSK. Facial gingival tissue stability following immediate placement and provisionalization of maxillary anterior single implants: a 2- to 8-year follow-up. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;106(5):342.

Mailoa J, Arnett M, Chan HL, George FM, Kaigler D, Wang HL. The association between buccal mucosa thickness and periimplant bone loss and attachment loss: a cross-sectional study. Implant Dent. 2018;27(5):575–81.

Fu JH, Su CY, Wang HL. Esthetic soft tissue management for teeth and implants. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2012;12(3 SUPPL.):129–42.

Thoma DS, Gasser TJW, Jung RE, Hämmerle CHF. Randomized controlled clinical trial comparing implant sites augmented with a volume-stable collagen matrix or an autogenous connective tissue graft: 3-year data after insertion of reconstructions. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(5):630–9.

Lee A, Fu JH, Wang HL. Implant success. Implant Dent. 2011;20(3):38–47.

Thoma DS, Gasser TJW, Jung RE, Hämmerle CHF, Donos N, Horvath A, et al. Soft tissue augmentation around osseointegrated and uncovered dental implants: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;21(1):152–77.

Fuentealba R, Jofré J. Esthetic failure in implant dentistry. Dent Clin. 2015;59:8532.

Abou-arraj RV. Soft tissue grafting around implants: why, when, and how ? Curr Oral Health Rep Orig. 2020;7:381–96.

Zucchelli G, Mele M, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C, Marzadori M, Montebugnoli L, et al. Patient morbidity and root coverage outcome after subepithelial connective tissue and de-epithelialized grafts: a comparative randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:728–38.

Frizzera F, de Freitas RM, Muñoz-Chávez OF, Cabral G, Shibli JA, Marcantonio E Jr. Impact of soft tissue grafts to reduce peri-implant alterations after immediate implant placement and provisionalization in compromised sockets. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2019;39(3):381–9.

Migliorati M, Amorfini L, Signori A, Biavati AS, Benedicenti S. Clinical and aesthetic outcome with post-extractive implants with or without soft tissue augmentation: a 2-year randomized clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17:983–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12194.

Atieh MA, Alsabeeha NHM. Soft tissue changes after connective tissue grafts around immediately placed and restored dental implants in the esthetic zone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020;32(3):280–90.

González-Martín O, Lee E, Weisgold A, Veltri M, Su H. Contour management of implant restorations for optimal emergence profiles: guidelines for immediate and delayed provisional restorations. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2020;40(1):61–70.

Meloni SM, Riu GD, Pisano M, Riu ND, Tullio A. Immediate versus delayed loading of single mandibular molars. One-year results from a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012;5(4):345–53.

Cannizzaro G, Torchio C, Felice P, Leone M, Esposito M. Immediate occlusal versus non-occlusal loading of single zirconia implants. A multicentre pragmatic randomised clinical trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2010;3(2):111–20.

Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Maghaireh H, Worthington HV. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: different times for loading dental implants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003878.pub5.

Zuffetti F, Esposito M, Galli F, Capelli M, Grandi G, Testori T. A 10-year report from a multicentre randomised controlled trial: immediate non-occlusal versus early loading of dental implants in partially edentulous patients. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2016;9(3):219–30.

Raes F, Cosyn J, De Bruyn H. Clinical, aesthetic, and patient-related outcome of immediately loaded single implants in the anterior maxilla: a prospective study in extraction sockets, healed ridges, and grafted sites. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2013;15(6):819–35.

Wiesner G, Esposito M, Worthington H, Schlee M. Connective tissue grafts for thickening peri-implant tissues at implant placement. One-year results from an explanatory split-mouth randomised controlled clinical trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2010;3(1):27–35.

Hutton CG, Johnson GK, Barwacz CA, Allareddy V, Avila-Ortiz G. Comparison of two different surgical approaches to increase peri-implant mucosal thickness: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2018;89(7):807–14.

Poli PP, Maridati PC, Stoffella E, Beretta M, Maiorana C. Influence of timing on the horizontal stability of connective tissue grafts for buccal soft tissue augmentation at single implants: a prospective controlled pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(6):1170–9.

Wang Y, Stathopoulou PG. Tunneling techniques for root coverage. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2019;6(4):237–43.

Delgado-Ruiz R, Gold J, Marquez TS, Romanos G. Under-drilling versus hybrid osseodensification technique: differences in implant primary stability and bone density of the implant bed walls. Materials. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13020390.

Zuhr O. The addition of soft tissue replacement grafts in plastic periodontal and implant surgery: critical elements in design and execution. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:s125–42.

Zuiderveld EG, Meijer HJA, den Hartog L, Vissink A, Raghoebar GM. Effect of connective tissue grafting on peri-implant tissue in single immediate implant sites: a RCT. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(2):253–64.

Buser D. Optimizing esthetics for implant restorations in the anterior maxilla: anatomic and surgical. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004;43(19):43–61.

Furhauser R. Evaluation of soft tissue around single-tooth implant crowns: the pink esthetic score. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;16(January):639–44.

Cairo F, Barbato L, Tonelli P, Batalocco G, Pagavino G, Nieri M. Xenogeneic collagen matrix versus connective tissue graft for buccal soft tissue augmentation at implant site. A randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(7):769–76.

James WC, McFall WT Jr. Placement of free gingival grafts on denuded alveolar bone. Part I: clinical evaluations. J Periodontol. 1978;49(6):283–90.

Rateitschak KH, Egli U, Fringeli G. Recession: a 4-year longitudinal study after free gingival grafts. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6(3):158–64.

Tomasek JJ, Haaksma CJ, Schwartz RJ, Howard EW. Whole animal knockout of smooth muscle alpha-actin does not alter excisional wound healing or the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21(1):166–76.

Klingberg F, Hinz B, White ES. The myofibroblast matrix: implications for tissue repair and fibrosis. J Pathol. 2013;229(2):298–309.

Sculean A, Gruber R, Bosshardt DD. Soft tissue wound healing around teeth and dental implants. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(Suppl 15):S6-22.

De Rouck T, Collys K, Wyn I, Cosyn J. Instant provisionalization of immediate single-tooth implants is essential to optimize esthetic treatment outcome. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20(6):566–70.

Becker CM Jr, TGW. Minimum criteria for immediate provisionalization of single-tooth dental implants in extraction sites: a 1-year retrospective study of 100 consecutive cases. YJOMS. 2011;69(2):491–7.

Boujoual I, Andoh A. Immediate vs delayed implant loading: the current status of the literature. Int J Curr Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13034.62403.

Den Hartog L, Raghoebar GM, Stellingsma K, Vissink A, Meijer HJA. Immediate non-occlusal loading of single implants in the aesthetic zone: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(2):186–94.

Hall JAG, Payne AGT, Purton DG, Torr B, Duncan WJ, De Silva RK. Immediately restored, single-tapered implants in the anterior maxilla: prosthodontic and aesthetic outcomes after 1 year. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2007;9(1):34–45.

Oh TJ, Shotwell JL, Billy EJ, Wang HL. Effect of flapless implant surgery on soft tissue profile: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2006;77(5):874–82.

Kao RT, Fagan MC, Conte GJ. Thick vs. thin gingival biotypes: a key determinant in treatment planning for dental implants. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2008;36(3):193–8.

Linkevicius T, Apse P, Grybauskas S, Puisys A. The influence of soft tissue thickness on crestal bone changes around implants: a 1-year prospective controlled clinical trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24(4):712–9.

ITI. SAC Assessment Tool. 2011. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14491.05921.

Romeo E, Lops D, Rossi A, Storelli S, Rozza R, Chiapasco M. Surgical and prosthetic management of interproximal region with single-implant restorations: 1-year prospective study. J Periodontol. 2008;79(6):1048–55.

Poskevicius L, Galindo-moreno P. Dimensional soft tissue changes following soft tissue grafting in conjunction with implant placement or around present dental implants: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implantol Res. 2015;28:1–8.

Puisys A, Linkevicius T. The influence of mucosal tissue thickening on crestal bone stability around bone-level implants. A prospective controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015;26(2):123–9.

Cosyn J, Bruyn HD, Cleymaet R. Soft tissue preservation and pink aesthetics around single immediate implant restorations: a 1-year prospective study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2012;15:847–57.

Bruyckere TD, Cosyn J, Younes F, Bekx J, Cleymaet R, Eghbali A. A randomized controlled study comparing guided bone regeneration with connective tissue graft to re-establish buccal convexity: one-year aesthetic and patient-reported outcomes. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2020;31:507–16.

Rojo R, Prados-Frutos JC, Manchón Á, Rodríguez-Molinero J, Sammartino G, Calvo Guirado JL, et al. Soft tissue augmentation techniques in implants placed and provisionalized immediately: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7374129.

De Bruyckere T, Eghbali A, Younes F, De Bruyn H, Cosyn J. Horizontal stability of connective tissue grafts at the buccal aspect of single implants: a 1-year prospective case series. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(9):876–82.

Zeltner M, Jung RE, Hämmerle CHF, Hüsler J, Thoma DS. Randomized controlled clinical study comparing a volume-stable collagen matrix to autogenous connective tissue grafts for soft tissue augmentation at implant sites: linear volumetric soft tissue changes up to 3 months. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(4):446–53.

Rungcharassaeng K, Kan JYK, Yoshino S, Morimoto T, Zimmerman G. Immediate implant placement and provisionalization with and without a connective tissue graft: an analysis of facial gingival tissue thickness. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2012;32(6):657–63.

Rojo E, Stroppa G, Gonzalez-martín O, Nart J. Soft tissue stability around dental implants after soft tissue grafting from the lateral palate or the tuberosity area—a randomized controlled clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:892–9.

Magdy M, Abdelkader MA, Alloush S, Fawzy El-Sayed KM, Nawwar AA, Shoeib M, ElNahass H. Ultra-short versus standard-length dental implants in conjunction with osteotome-mediated sinus floor elevation: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12995.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The study was self-funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF: conceived the idea and conducted the clinical trial. MH: supervised the project. HEN: co-conceived the idea and led the writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry, Cairo University University (January 2019) and registered in the Clinical Trials Registry (clinicalTrials.gov) NCT03792425. The CONSORT guidelines for randomized clinical trials were followed. The detailed surgical procedures and follow-up periods were clearly described to all patients who participated in this clinical trial before signing the informed consent that extends to allow publication of the data.

Consent for publication

All patients signed a consent form that allows the publication of the data and pictures collected within the frame of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fawzy, M., Hosny, M. & El-Nahass, H. Evaluation of esthetic outcome of delayed implants with de-epithelialized free gingival graft in thin gingival phenotype with or without immediate temporization: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Implant Dent 9, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-023-00468-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-023-00468-0