Abstract

Background

The produced mechanical work at tensile drawing is converted into heat almost completely and the polymer temperature rises. The temperature rise at adiabatic drawing for different polymers is 20-100°C.

Methods

To determine the temperature of PET during neck propagation, micro-particles with pre-determined melt surface were dusted on the sample surface. If particles melted, surface temperature exceeded the particle melt temperature. In addition, the temperature rise was analyzed theoretically.

Results

The surface temperature of 140°С of PET film samples was recorded. Equations describing distribution of temperature are derived. The equations are solved for steady neck propagation. The drawing ratio in the neck and the draw stress are the main parameters determining the temperature rise. A new method of measurement of the heat transfer coefficient from the neck temperature profile is developed.

Conclusions

When the temperature in the yield zone reaches the glass transition temperature, appear pores, the neck drawing ratio increases, and further temperature rises are observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amorphous polymers are stretched to improve the strength and the Young's modulus. If drawing occurs without application of external heat, the process is called cold drawing. Drawing is often done at room temperature and thus called a cold drawing. However, it may be performed at elevated temperatures lower than the glass transition temperature.

When a strip of film is stretched with a constant rate, initially homogeneous extension evolves into a non-homogeneous motion in which the strip thins down in a short region along its length and forms a neck. Initially, the neck lengthens and deepens. However, eventually it grows in length without further change of depth. Outside of the neck, the material is in a state of low stretch; within the neck, stretch is high. The transition zone during a drawing process moves along the sample with a constant velocity. Upon the passage of this zone through a region, the material in that region is taken from the state of low stretch to the state of high stretch.

According to Joule, mechanical work done in liquids is converted into heat, and the temperature of the liquid increases. A different behavior is observed in elastic materials. Under tension, the temperature of elastic materials decreases. The effect was predicted by Thomson (1853) and found experimentally by Joule (Joule and Thomson 1856). Glassy polymers exhibit both types of behavior. At low tensile strains, deformation is elastic and temperature decreases (Muller 1962; Haward 1994). After the onset of yielding, the sign of the thermal effect changes and temperature rises (VonEngelter and Muller 1958; Andrianova et al. 1978; Godovsky 1992; Salamatina et al. 1989; Rittel 1999; Hillmansen and Haward 2001; Haward 2003; Wunderlich 2007; Leevers and Godart 2008; Nasraoui et al. 2009; Wunderlich 2011; Swallowe 2012).

The magnitude of temperature change at cold drawing is much higher than that at elastic deformation. The temperature decrease at elastic deformation does not exceed 1 K. The temperature rise, ∆T, for drawing of polyvinylchloride (PVC) was estimated by Engelter and Muller as 59°C (VonEngelter and Muller 1958). They assumed that the work done in drawing is completely converted into heat. This assumption was confirmed experimentally for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) (Andrianova et al. 1978). However, usually some fraction of the produced work is accumulated as internal energy. The typical ratio of the generated heat to the produced work, Q/A, for polymer drawing is 0.7 to 0.9 (Godovsky 1992; Salamatina et al. 1989). The ratio Q/А for low-density polyethylene (LDPE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polypropylene (PP), and polyamide-6 does not depend on the drawing rate (Godovsky 1992). In contrast, for amorphous PET, the ratio Q/А increases from 0.95 at low drawing rates, V, to 1.3-1.35 at V = 120 mm/min. Q/А exceeds unity due to crystallization of PET at high drawing rates (Godovsky 1992).

At low drawing rates, the generated heat is dissipated into the environment and the temperature rise may be neglected (Müller and Brauer 1954; Ward 1984; Koenen 1994; Toda et al. 2002). The temperature grows with the drawing rate (Koenen 1994; Toda et al. 2002). Different non-systematized and sometimes inconsistent data for the magnitude of the temperature rise were reported. A 25°C temperature rise, ∆T, was observed in polycarbonate (PC) in room conditions at a drawing rate V = 307 mm/min (Koenen 1994), and for PET, the temperature T = 84°C was recorded at V = 500 mm/min (Toda et al. 2002). For PET, the temperature T = 120°С was reported in room conditions (Kechekyan et al. 1970). The thermo-mechanical fracture of PET was observed at high drawing rates (Kechekyan et al. 1970; Hillmansen and Haward 2001; Haward 2003).

The temperature rise in the neck for adiabatic drawing conditions is described by the Engelter-Muller equation which was modified to consider the fraction of mechanical work accumulated by a polymer (Hillmansen and Haward 2001):

where σd represents the drawing stress, ρ the density, с the heat capacity of a polymer, λ = L/L0 the natural drawing ratio in the neck, L0 the initial length of a sample, L its length after neck propagation, and α = Q/А the fraction of work converted into heat.

The polymer drawing stress, density, heat capacity, and the natural drawing ratio, λ, are usually considered material constants independent of temperature and the drawing speed. For example, for PET and PA-6, the drawing ratio, λ, does not depend on temperature and drawing rate (Godovsky 1992). However, at high drawing rates (>100 mm/min), an increase in the drawing ratio, λ, was observed for PET and PP (Liu and Harrison 1988; Bazhenov 2011). An increase in λ with temperature was observed for PC (Chiang et al. 2013) and HDPE (Serenko et al. 2003). In contrast, the drawing ratio, λ, of PET decreases as it approaches the glass transition temperature (Rietsch et al.).

The theory of temperature rise at non-adiabatic neck propagation was founded by Barenblatt (1970). The theory assumes that the produced work is converted into heat in a thin transition region between the neck and non-oriented part of the drawn sample. The theory was modified by Toda who used a classical heat diffusion equation (Toda 1994). For PET, Toda's equation predicts a maximum temperature rise in the neck, ∆T, as 20°C to 25°C. However, in experiments, substantially higher temperature was registered (Toda et al. 2002). On this reason, a fitting parameter, multiplying the temperature rise by a factor 2.5, was used (Toda 1994). Bazhenov corrected Toda's equation and obtained reasonable agreement with experimental data for high drawing rates without any fitting parameters (Bazhenov 2011). However, for low drawing rates, the equation used in (Bazhenov 2011) is not accurate.

The goal of the present work is to study the temperature rise at cold drawing of PET.

Methods

Commercial films of amorphous non-oriented PET were tested in tension at a constant drawing rate. The thickness of the films was 170 μm. The samples were straight strips cut from the polymer film. The width of test samples was 5 mm, and the gauge length was 20 mm. To initiate necking in the gauge part, the samples were bent in their center before testing. Tensile tests were performed at room temperature with a Shimadzu Autograph AGS-H universal testing machine (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

To determine temperature of the PET sample surface during neck propagation, organic particles with different melting points were prepared. With this aim, phenazitil and benzanilide with melting points of 137°С and 161°С, respectively, were mixed. The melting temperatures of mixtures were changed by variation of the component fractions. Mixtures were stirred in liquid state. After cooling, mixtures were ground in a mortar to obtain particles with a size 10 to 20 μm. The melting point of the powder particles was determined with a temperature stage of an optical microscope in polarized light. The particles were studied in the microscope, and the melting temperature was determined with an accuracy of 1°C.

Obtained particles were dusted on the surface of the PET samples. If particles did not melt during sample drawing, they were removed from the sample surface with a cotton wool. If particles melted, they were adhered to a surface. In this case, the experiment was repeated using particles with higher melting temperature. The neck temperature was determined with a precision of 5°С.

Analysis

Figure 1 shows the photograph of the neck propagating through a PET sample. The unoriented part of the sample and the neck are separated by a transition zone where the polymer is oriented and heat is released. The length of the transition zone is close to the thickness of the test film. The equation describing temperature in the non-oriented part of the sample is derived in the Appendix:

where T(x) is the temperature in point x (Figure 2), a = (χ/ρc)1/2, ρ is the density, c the heat capacity, χ the coefficient of thermal conductivity of a polymer, h the thickness, w the width of the sample, T o the temperature of the surrounding, and β the heat transfer coefficient (heat dissipated in surrounding per 1 m2 surface on 1 K temperature difference).

Schematic of the neck propagation. The origin of the moving coordinate system is placed in the transition zone region between the neck and non-oriented part of the sample. V, the cross-head speed; dx, the length of the sample element; Δx, the length of the transition zone; u, the speed of non-oriented part of the sample; V + u, the speed of the neck.

The neck temperature is described by an equation derived in the Appendix:

where hn is the film thickness in the neck.

Assuming that the length of the transition zone Δx is very short, the solution of Equations 2 and 3 for steady neck propagation is

where ∆T is the temperature rise in the transition zone. Equation 4 at high drawing rates (V2ρ2c2/(λ − 1)2 >> 8βχ/h) gives Equation 1 derived from first principles (Hillmansen and Haward 2001; Bazhenov 2011). Note that the theory determines temperature rise ∆T, while in experiments, temperature T is measured. Below the temperature of a surrounding air, T0, is assumed equal to 22°C.

Drawing conditions are adiabatic if heat losses to surroundings may be neglected. Considering Equation 4, this condition is fulfilled at V >> Vc, where

Vc characterizes the drawing rate of the transition from isothermal to adiabatic conditions. Drawing is isothermal at V << Vc. The typical values of Vc are presented in Table 1 for different polymers. Vc is comparatively close for all presented polymers. However, Vc depends on the sample thickness.

Results

Adiabatic drawing

Figure 3 shows a typical engineering tensile stress σ plotted against strain ε. The horizontal part of the curve corresponds to steady neck propagating through the sample.

The temperature of the PET film in the neck was measured in room conditions at a drawing rate of 1,000 mm/min as described in the ‘Methods’ section. The temperature, T, was determined as 140°С ± 5°С. According to theoretical estimation, the adiabatic temperature rise for PET is ∆T = 57°C (Ward 1984). This value is half of the ∆T = 140 − 22 = 118°С measured in this work. To explain the difference, parameters of Equation 1 were measured as a function of the drawing rate.

Figure 4 shows the drawing ratio of PET in the neck, λ, plotted against the cross-head speed, V. At low cross-head speeds, drawing ratio λ = 4.5. Further increase of the cross-head speed to 1,000 mm/min leads to an increase in λ. Approximation of the curve by two straight lines shows that the onset of λ increase is observed at V = 70 to 80 mm/min.

Figure 5 shows the PET drawing stress, σd, plotted against the cross-head speed, V. The curve is N-like in shape. At low drawing rates, the temperature rise may be neglected, and σd grows with V. At medium drawing rates, from 5 to 100 mm/min, the draw stress decreases due to heat softening of the polymer. At high drawing rates, the draw stress, σd, increases with V.

Figure 6 shows the ratio of the released heat to the produced mechanical work, α = Q/А, plotted against the cross-head speed, V. The ratio Q/А increases from 0.95 at V = 2 mm/min to 1.30-1.35 at V = 120 mm/min. This is explained by crystallization heat at high drawing rates.

The fraction of work converted into heat,α = Q/A, plotted against the cross-head speedV. Experimental data are taken from (Godovsky 1992).

Adiabatic temperature rise of PET for the drawing rate V = 1,000 mm/min was calculated at ρ = 1,332 kg m−3, α = 1.325 (Figure 6), σd = 37 MPa, λ = 6.5, с = 1,130 J kg−1 K−1, β = 51 J m−2 s−1, and χ = 0.14 J m−2 s−1 K−1 (Bazhenov 2011). Using Equation 1, ∆T = 170°С was obtained. The temperature rise is high, and the heat capacity in the interval of 23°С to 193°С is not constant. For this reason, the heat capacity at T < Tg (75°С) was instead described by the expression (van Krevelen and te Nijenhuis 2009)

At T > Тg, it was described (van Krevelen and te Nijenhuis 2009) as

The temperature was calculated by solution of the equation:

Numerical solution of Equation 8 gives T = 159°С. This value is close to the experimentally measured value T = 140°С.

Table 1 presents parameters determining temperature rise, ΔT, for different polymers. Figure 7 shows the typical values of adiabatic temperature rise, ΔT, calculated with Equation 8 for different polymers. ΔT is relatively low for LDPE, PC, HDPE, PVC, and PP: 20°C, 26°C, 28°C, 28°C, and 43°C, respectively. The calculated value ΔT = 26°C for PC practically coincides with the experimental value of 23°C to 25°C (Koenen 1994). ΔT for PA-6, PA-66, and PET is high: 74°C and 137°C, respectively. For the last two polymers, the adiabatic temperature increase from room temperature would exceed the glass transition temperature Tg. Temperature rise is especially high for PET due to the combination of high drawing stress, σd, and high drawing ratio, λ.

Non-adiabatic drawing

Figure 8 shows the temperature, T, in the PET neck, plotted against the cross-head speed, V. Drawing ratio and drawing stress were taken from Figures 3 and 4. At V < 2 mm/min, the ratio α was considered constant equal to 0.95. At V > 120 mm/min, α = 1.325 was taken. Temperature, T, was calculated assuming that the volume of polymer at drawing does not change and the film thickness in the neck hn = h/λ. However, at high drawing rates, PET voids and this assumption is not fulfilled. At low V, the temperature is close to 22°C. Usually, it is considered that at high cross-head speeds, the temperature approaches the adiabatic limit and does not exceed some value. However, in Figure 8, there is no asymptotic limit due to an increase in the drawing ratio, λ, and draw stress, σd, with the drawing velocity. In other words, the testing conditions are adiabatic, but the value of adiabatic limit increases with drawing rate.

Distribution of temperature in the neck is described by an equation derived in the Appendix:

where θ is the temperature rise in point x (−x is the distance from the heat generation plane, Figure 9).

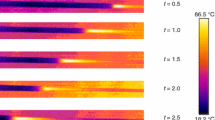

Figure 10 shows the profile of temperature rise in the neck, θ, measured with an IR camera at the drawing speed V = 100 mm/min (Toda et al. 2002). The temperature rise in coordinates of Equation 9 (i.e., ln θ − x) is described by a straight line. The slope of the straight line γ2 (Equation 25) is 190 m−1. Considering Equation 25, coefficient β is given by

The temperature rise in PET neck plotted against the distance from the yield plane, x. The drawing velocity V = 100 mm/min, h = 0.6 mm, and w = 10 mm (Toda et al. 2002).

Equation 10 may be used to determine the heat transfer coefficient β if the slope of the straight line, γ2, was measured. Neglecting reduction of the sample width in the neck and assuming that the volume of polymer at drawing does not change, the film thickness in the neck hn = h1/λ. For γ2 = 190 m−1, V = 100 mm/min, and h1 = 0.6 mm, the value β = 51 Wt/(m2 K) was obtained. This value is close to β = 75 Wt/(m2 K) determined by measurement of temperature of carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy plate heated by electric current (Bazhenov and Kechekyan 2001). The size of the plate was 0.5 × 0.6 m.

Discussion

The temperature rise at cold drawing of PET may be very high. Muller understood that the temperature rise, ∆T, in polymers at cold drawing may be significant [3–5]. The temperature rise for PVC was estimated from the first principles as 59°C, and the problem looked closed. However, for PET temperature rise, ∆T was calculated as 57°C (Toda 1994), while in experiments, substantially higher ∆T = T − T0 ≈ 100°C was recorded (Kechekyan et al. 1970). In addition, heating-induced fracture was observed at high drawing rates (Kechekyan et al. 1970). Melting of PET fibers near a fracture plane was observed (Hearle et al. 1998). This paper explains the mechanism of this unexpectedly high temperature rise in PET.

Usually, it is considered that temperature rise at high drawing rates approaches some adiabatic temperature limit. However, the adiabatic limit is not constant and increases with the drawing rate. The higher the drawing rate, the higher the temperature rise. The main reason for the increase of the temperature is an increase of the drawing ratio, λ, at high drawing rates.

The increase in the drawing ratio, λ, is explained by reaching the glass transition temperature. The onset of λ increase in Figure 3 is observed at V = 70 to 80 mm/min. According to Figure 7, the temperature at V = 70 to 80 mm/min is 80°С to 85°С, slightly higher than the glass transition temperature Tg of PET (≈75°С). At T > Tg, the polymer is a viscous liquid, and the drawing ratio in neck increases.

Usually, the fraction of work converted into heat, α = Q/А, is measured by calorimeter. However, Equation 1 may be used as an alternative method of α measurement or for checking the accuracy of calorimeter measurements. With this aim, temperature rise, ∆T, should be measured accurately. However, for light transparent polymers, industrially produced devices may give incorrect data. In this case, the special method described by Koenen must be used (Koenen 1994).

The neck of PET samples at drawing rates V < 100 mm/min is transparent. However, at higher drawing rates, the neck whitens due to appearance of several cavities. Figure 11a shows a SEM image of pores observed in the neck at high drawing rates. The pores are elongated in the drawing direction. Pores appear if the temperature in the transition zone is higher than the glass transition temperature Tg of PET. Cavitation is initiated in shear yield lines in front of the transition zone (Figure 11b).

Figure 9 illustrates schematically the changes in the PET deformation conditions with an increase in the drawing rate. At low drawing rates (in region 1), the polymer temperature is close to the room temperature. In region 2, the temperature rises, but the polymer properties do not change significantly. Particularly, drawing ratio remains constant. When the temperature reaches the glass transition temperature Tg, the polymer becomes a viscous liquid and its properties change. Particularly, the drawing ratio increases. As a result, the adiabatic temperature increases. Finally, the thermal fracture is observed (region 4) (Kechekyan et al. 1970; Hearle et al. 1998).

Conclusions

-

1.

The temperature in the PET neck reaches 140°С at a cross-head speed of 1,000 mm/min.

-

2.

The theoretical value of temperature T = 159°С is close to the experimental value of 140°С.

-

3.

The temperature of adiabatic temperature rise is calculated for different polymers.

-

4.

Differential equation describing temperature in the neck is derived.

-

5.

Equation describing temperature at non-adiabatic neck propagation is derived.

-

6.

Drawing rate of the transitions from isothermal to adiabatic drawing conditions is determined.

-

7.

High temperature rise in the PET neck is explained by low glass transition temperature Tg. When Tg is reached, the drawing ratio in the neck increases and pores appear. This leads to additional increase of neck temperature.

-

8.

A new method of measurement of heat transfer coefficient from the neck temperature profile was developed.

References

Andrianova, GP, Arutyunov, BA, & Popov, YV. (1978). Calorimetric studies of polyethylene terephthalate stretching over a wide temperature range. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Physics, 16, 1139–1154. doi:10.1002/pol.1978.180160701.

Barenblatt, GI. (1970). Self-oscillating neck propagation in polymers. Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Mechanics of Solids, 5, 110–118.

Bazhenov, S. (2011). Self-oscillatory neck propagation in polymers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 119, 654–661. doi:10.1002/app.32804.

Bazhenov, SL, & Kechekyan, AS. (2001). A criterion for the onset of mechanical self-oscillations during neck growth in a polymer film under tensile stress. Polymer Science, Series A, 43, 52–60.

Chiang, D, Tsai, M-L, & Lee, S. (2013). The tensile force oscillation of polycarbonate at elevated temperatures. Polymer Engineering and Science, 53, 589–596.

Godovsky, YK. (1992). Thermophysical properties of polymers. Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1002/adma.19920041018.

Haward, RN. (1994). Heating effects in the deformation of thermoplastics. Thermochimica Acta, 247, 87–109.

Haward, RN. (2003). The adiabatic fracture of thermoplastic fibres. Journal of Materials Science, 38, 2155–2160. doi:10.1023/A:1023771929564.

Hearle, JWS, Lomas, B, & Cooke, WD. (1998). Atlas of fibre fracture and damage to textiles. Boca Raton: C.R.C.. ISBN 1855733196.

Hillmansen, S, & Haward, RN. (2001). Adiabatic failure in polyethylene. Polymer, 42, 9301–9312. doi:10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00447-5.

Joule, J, & Thomson, W. (1856). On the thermal effects of longitudinal compression of solids. Proceedings Royal Society of London, 8, 564–569.

Kechekyan, AS, Andrianova, GP, & Kargin, VA. (1970). Periodic oscillations at drawing of polyethyleneterephtalate. Polymer Science Ser A, 12, 2424–2435.

Koenen, JA. (1994). Quantitative measurement of the heat exchange during deformation using an infrared camera. Thermochimica Acta, 247, 55–64. doi:10.1016/0040-6031(94)80113-4.

Leevers, PS, & Godart, M-A. (2008). Adiabatic decohesion in a thermoplastic craze thickening at constant or increasing rate. Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 56, 2149–2170. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2008.02.001.

Liu, T, & Harrison, IR. (1988). Effect of draw rate on the stress–strain behavior of polymers. Polymer, 29, 233–239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0032-3861(88)90327-8.

Muller, FH. (1962). Nichtlineare deformation II. Kolloid-Zeitschrift und Zeitschrift für Polymere, 183, 120–134.

Müller, EH, & Brauer, Р. (1954). Uber die Temperaturüberhöhung in der Eliebzone wahrend der Kaltverstreckung. Kolloid-Zeitschrift, 155, 65–67.

Nasraoui, M, Forquin, P, Siad, L, & Rusinek, A. (2009). Influence of strain rate, temperature and adiabatic heating on the mechanical behaviour of polymethyl-methacrylate: experimental and modelling analyses. Materials and Design, 37, 500–509. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2011.11.032.

Pakula, T, & Fischer, EW. (1981). Instabilities of the deformation process during cold drawing of poly(ethyleneterephthalate) and other polymers. Journal of Polymer Science, Polymer Phys, 19, 1705–1726.

Rietsch, F, Duckett, RA, & Ward, IM. (1979). Tensile drawing behaviour of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Polymer, 20, 1133–1142.

Rittel, D. (1999). On the conversion of plastic work to heat during high strain rate deformation of glassy polymers. Mechanics of Materials, 31, 131–139. doi:10.1016/S0167-6636(98)00063-5.

Salamatina, OB, Nazarenko, SI, Rudnev, SN, & Oleinik, EF. (1989). Heat effects and the mechanism of inelastic deformation of organic glassy polymers. Mechanics of Composite Materials, 24, 721–725. doi:10.1007/BF00610773.

Serenko, OA, Goncharuk, GP, Obolonkova, ES, Bazhenov, SL, Nasrullaev, IN, & Magomedov, GM. (2003). Effect of temperature on the fracture mechanism of a polyethylene-rubber composite. Polymer Sci, Ser A, 45, 1153–1160.

Swallowe, GM. (2012). Adiabatic shear bands in polymers. In B Dodd & Y Bai (Eds.), Adiabatic shear localization (pp. 363–398). Amsterdam: Frontiers and Advances Elsewier.

Thomson, W. (1853). On the dynamic theory of heat; with numerical results deduced from Mr. Joule's equivalent of a thermal unit and M. Regnault's observation on steam. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 20, 261–298. doi:10.1080/14786445208647064.

Toda, A. (1994). Oscillatory neck propagation in polymer films. Polymer, 35, 3638–3642. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(94)90540-1.

Toda, A, Tomita, C, Hikosaka, M, Hibino, Y, Miyaji, H, Nonomura, C, Suzuki, T, & Ishihara, H. (2002). Thermo-mechanical coupling and self-excited oscillation in the neck propagation of PET films. Polymer, 43, 947–951. doi:10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00625-5.

van Krevelen, DW, & te Nijenhuis, K. (2009). Properties of polymers, their correlations with chemical structure. Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.1002/pol.1981.180191104.

VonEngelter, A, & Muller, FH. (1958). Thermische effecte bei mechanischer deformation, insbesondere von hochpolymeren. Kolloid-Zeitschrift, 157, 89–111.

Ward, IM. (1984). Mechanical properties of solid polymers. Chichester: Wiley.

Wunderlich, B. (2007). Calorimetry of nanophases of macromolecules. International Journal of Thermophysics, 28, 958–967. doi:10.1007/s10765-007-0227-6.

Wunderlich, B. (2011). Do biopolymers behave the same as synthetic high polymers? Journal of Therm Anal and Calorim, 106, 81–84. doi:10.1007/s10973-011-1306-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Neck propagation velocity

Figure 2 shows a schematic of the neck propagating along a film sample. If the length of the non-oriented part of the sample decreases by dx, the increment of the neck length is λ dx. The increment of the sample length is equal to that of the neck length minus the decrease of the non-oriented part:

Division of both parts of Equation 11 by dt gives

The left part of Equation 12 is the cross-head speed V, and u = dx/dt - the neck propagation velocity:

This equation was derived by Pakula and Fischer (1981).

Thermal balance

The length of the transition zone is assumed to be very short (∆x → 0). The origin of the coordinate axis X is placed in the transition zone. The velocities of the non-oriented part of the sample and of the neck are u and V + u, respectively (Figure 11). A very thin element of the non-oriented part of the sample is shown in Figure 11. If dx is the length of the element, the income of heat in it for time dt due to thermoconductivity is

where T(x) is the temperature at point x, and χ is the coefficient of thermal conductivity. Similarly, the heat flow out of the element is

The total shadowed surface area of the element, contacting with air is S = 2(w + h) dx. Assuming that the heat transferred to the surroundings, dQ3 is proportional to the local temperature rise T − T0 and the surface area S, dQ 3 is given by

where S = 2(w + h) dx, w is the sample width, h the film thickness, and dx the length of the element.

The heat dQ1 − dQ2 − dQ 3 is spent on the change of the element temperature:

Taking into account that the transitional zone moves with velocity u, Equation 2 is obtained. Considering a similar element in the neck and taking into account its velocity V + u = λu with respect to the transition zone, for the neck temperature, Equation 3 is obtained.

Assuming that the length of the transition zone Δx is very thin (Δx → 0), the heat released in the transition zone is equal to the heat fluxes to the non-oriented part of the sample and to the neck:

The boundary conditions on infinity are

Steady neck propagation solution

At steady neck propagation ∂T/∂t = 0. Substitution of T(x) = θ(x) + T0 in Equation 2 gives

where p = uρc/χ and q1 = 2β(h + w)/(whχ), and θ(x) - the local temperature rise.

Substitution of T(x) = θ(x) + T0 in Equation 3 gives

where q2 = 2β(hn + w)/(whnχ), and hn - the thickness of the sample in the neck.

The boundary conditions are θ → 0 at x → +∞ and θ → 0 at x → −∞. The solution of Equations 20 and 21 is

where ∆T = θ(0) is the temperature rise in the transition zone. Substitution of Equation 22 into Equation 23 gives γ12 − pγ1 − q1 = 0. This equation has two solutions:

To comply θ → 0 at x → +∞, γ1 must be positive at x > 0. Hence, the sign is ‘+’, and the temperature rise in the non-oriented part of sample is

Similarly, substitution of Equation 22 into Equation 21 gives γ22 − λpγ2 − q2 = 0. To comply θ → 0 at x → −∞, the solution is

Thus, temperature rise in the neck is given by Equation 9.

Finally, substitution of Equations 23 and 24 into Equation 18 gives Equation 4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bazhenov, S. Non-adiabatic heating of polymer films under drawing. Int J Mech Mater Eng 9, 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-014-0001-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-014-0001-z