Abstract

Background

Within the highly bio-diverse ‘Northern Vietnam Lowland Rain Forests Ecoregion’ only small, and mostly highly modified forestlands persist within vast exotic-species plantations. The aim of this study was to elucidate vegetation patterns of a secondary hillside rainforest remnant (elevation 120–330 m, 76 ha) as an outcome of natural processes, and anthropogenic processes linked to changing forest values.

Methods

In the rainforest remnant tree species and various bio-physical parameters (relating to soils and terrain) were surveyed on forty 20 m × 20 m sized plots. The forest's vegetation patterns and tree diversity were analysed using dendrograms, canonical correspondence analysis, and other statistical tools.

Results

Forest tree species richness was high (172 in the survey, 94 per hectare), including many endemic species (>16%; some recently described). Vegetation patterns and diversity were largely explained by topography, with colline/sub-montane species present mainly along hillside ridges, and lowland/humid-tropical species predominant on lower slopes. Scarcity of high-value timber species reflected past logging, whereas abundance of light-demanding species, and species valued for fruits, provided evidence of human-aided forest restoration and ‘enrichment’ in terms of useful trees. Exhaustion of sought-after forest products, and decreasing appreciation of non-wood products concurred with further encroachment of exotic plantations in between 2010 and 2015. Regeneration of rare tree species was reduced probably due to forest isolation.

Conclusions

Despite long-term anthropogenic influences, remnant forests in the lowlands of Vietnam can harbor high plant biodiversity, including many endangered species. Various successive future changes (vanishing species, generalist dominance, and associated forest structural-qualitative changes) are, however, expected to occur in small forest fragments. Lowland forest biodiversity can only be maintained if forest fragments maintain a certain size and/or are connected via corridors to larger forest networks. Preservation of the forests may be fostered using new economic incentive schemes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Astonishing new species discoveries during recent decades have highlighted Vietnamese forests’ biological richness (>11,300 vascular plants recorded) and high levels of endemism (~3% of vascular plant genera) (Wikramanayake et al. 2002; Sterling et al. 2006; MoNRE 2011). This has attracted attention from naturalists but also highlighted significant gaps in the knowledge and understanding of Vietnam’s biological heritage and corresponding significance for conservation (Sterling and Hurley 2005; Ceballos and Ehrlich 2009; Wilson et al. 2016). Notably, many discoveries were made in degraded forests which nonetheless support many potentially threatened species (Cochard et al. 2017).

Vietnam’s forests have been influenced by humans for centuries. Local communities extracted forest products for private use and for trade, promoted valuable tree species in nearby forests, and cleared forest areas for intermittent swidden agriculture (Fox et al. 2000; Wetterwald 2003; McElwee 2016). Sweeping impacts on forests ensued from French colonial forestry (McElwee 2016), and during the country’s struggle for independence large forest areas were damaged by impacts of war (especially aerial herbicides; Brauer 2009). Post-war logging and deforestation exacerbated as a result of timber exploitation by state forest enterprises (SFEs) or resource overuses following economic crises linked to collectivization and internal migration programs (De Koninck 1999; McElwee 2004, 2016).

During the 1990’s policy changes, aided by agricultural development, led to improvements in forest management. With support from international donors, large reforestation programs were set up. Local communities were supported financially and logistically to build tree nurseries and engage in reforestation. At the same time, forestlands were allocated to households and communities, with specific rights to harvest products, but also duties to improve and protect the allocated forests. As a result, many forests regenerated, partially aided by human interventions such as native-species tree planting, access restrictions, and fire controls (Meyfroidt and Lambin 2008; Cochard et al. 2017). Nonetheless, pressures from ‘illicit’ selective logging often remained high, especially in easily accessible forests (McElwee 2004, 2010). Threats are now increasingly posed by the boom in plantation forestry, especially within the biodiverse but poorly documented ‘Northern Vietnam Lowland Rain Forests Ecoregion’ (Wikramanayake et al. 2002). Since the late 1990s industrially managed exotic-species plantation forests (based on hybrid acacias used for pulp production) have expanded at fast rates and encroached on remaining natural forests in lowland areas (Thiha et al. 2007; McElwee 2009; Ha 2015; Cochard et al. 2017).

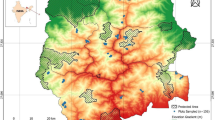

In hilly areas in southern parts of Thừa Thiên-Huế Province, transitional between the coastal plains and the inland Trường Sơn (Annamite) Mountain Ranges, a formerly extensive rainforest has been successively reduced and largely supplanted by exotic acacia plantations. Forest remnants are now mostly located in marginal areas, such as steep hillsides, or depressions near rivers (Fig. 1). In 2010 we conducted a vegetation survey in one major forest fragment (so-called ‘HPC-forest’). Residents of nearby villages continue to exploit forest products from this forest fragment (D.T. Ngo, pers. comm.). The aims of the study were to 1) record the fast disappearing forests’ tree composition and observe patterns of vegetation diversity within the context of ecology/biogeography as well as past and on-going anthropogenic influences, and 2) gain insights into forest values (in terms of timber and non-timber forest products) within past and current socio-economic contexts. The species composition of the forest fragment was, furthermore, discussed in regards to the isolation and continuing deforestation of the fragment – patterns and processes which may be representative for other cases of small-scale forests in the lower-lying areas of Central Vietnam.

Location of the HPC-forest study site within Thừa Thiên-Huế Province (upper images; red dot; the blue dots represent survey locations by Ha 2015). Middle images show the 40 study plots in the hillside forest fragment (orthogonal and southeast side views) in September 2012. This was still about the same extent (green outline; cover of 76 ha) as during the forest survey in July-August 2010. The lower images illustrate the forest cover changes in between May 2003 (blue forest outline; total cover 742 ha) and April 2014 (red forest outline; 39 ha). The coordinates of the highest plot (R1t-1; in yellow) are 16°13’7” N/107°42’48” E. Image sources: Wikipedia.org, mekong-protected-areas.org, and Google EarthTM

Methods

The study site

The study site was a secondary tropical evergreen broad-leaved monsoon forest fragment located on a west-facing hillside (elevation 120–340 m a.s.l.) within local authority of Hương Phú Commune (HPC) in Nam Đông District, Thừa Thiên-Huế Province, 30 km south of Huế City (Fig. 1). Nam Đông Valley extends south and is bounded by mountains in the east (Bạch Mã National Park), south and west (Central Trường Sơn or Annamite Ranges). The valley bottom is characterized by undulating topography with a patchwork of cultivated land, acacia plantations, and remnant forests. The forests of Nam Đông were traditionally used by Katu people (local minority ethnicity); today ethnic Vietnamese (Kinh) represent the majority (60%) of inhabitants in more urban areas of the district (Wetterwald 2003).

HPC-forest lies within the biodiverse but poorly studied and highly diminished/threatened ‘Northern Vietnam Lowland Rain Forests Ecoregion’ which extends for 22,500 km2 along a narrow coastal strip northwards from Thừa Thiên-Huế Province. The forest is, however, also in close vicinity to the better protected and documented ‘Southern Annamites Montane Rain Forests Ecoregion’ which covers adjacent mountainous areas (Wikramanayake et al. 2002). The climate in Nam Đông is wet-tropical (mean annual temperature 24.5 °C ± 0.4 °C; annual precipitation 373 cm ± 103 cm; relative humidity 85% ± 3%) with a fairly dry period January-July (but sufficient intermittent rainfalls to maintain evergreen ‘rainforest’), and a very wet monsoon period August-December (Fig. 2). Owing to climatic, biogeographic and geological factors, forest biodiversity is generally very high (Sterling et al. 2006). In nearby Bạch Mã National Park >2100 plant species have so far been recorded in addition to a richness of wildlife (Dickinson and Thinh 2006; Huynh et al. 2016).

Valuable timber has been extracted throughout the 20th century, changing the forests’ structure and composition. Acacia plantation forestry started in the 1990s (Thiha et al. 2007), displacing natural forests. Until 2003 HPC-forest was still embedded within a large forest area covering ~750 ha (Additional file 1: Figure S1). In 2010, when this study was conducted, HPC-forest was completely isolated within plantations, covering 76 ha. The cover was further reduced to 46 ha in 2014 and 39 ha in 2015. Twenty-three of forty plots surveyed in 2010 were thereby destroyed (Fig. 1). In 2015 the nearest contiguous forest was located 1.5 km east; another remnant forest (164 ha) was located 500 m north.

The vegetation survey

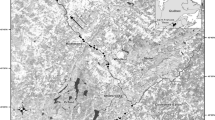

Within forty 20 m × 20 m square main plots (covering 1.6 ha or ~2% of HPC-forest) the vegetation was surveyed June-August 2010. The plots’ locations were determined in a semi-random fashion, using random points (set on Google EarthTM maps) as ‘starting points’, but finally selecting locations along accessible pathways (ridges or creeks) closest to the points. Plots were at least 30 m apart. Ten plots were finally located on slopes along a southern hillside ridge, nine along a northern ridge; remaining plots were located in lower-lying areas on slopes or local ridges mostly near to creeks (Figs. 1 and 3).

Classification and distribution of vegetation types in HPC-forest. Right panel: The dendrogram used for the classification (Ward linkage method, Manhattan distance algorithm). Left panel: The vegetation types (R-forest brown-yellow, B-forest blue-green) of the plots within the study site. The bubble size (area) indicates the relative total estimated above-ground woody biomass (TeAGB) on the plots. The plot axes indicate UTM coordinates, dim brown lines 20 m-contours, and blue lines show creeks

Within the plots we recorded species of all dicotyledonous trees, saplings and shrubs with a diameter at breast height (DBH) >2.5 cm, as well as woody monocotyledonous plants (only palms were found) of all sizes. DBH was measured 1.3 m above ground using a tree girth tape. We refer to ‘saplings’ (P) meaning trees/treelets/shrubs with a DBH ranging between 2.5 and <6 cm, following IFRI (2004; correspondingly, palm seedlings/saplings were defined using plant weight categories, cf. Additional file 2: Table S1-m). Stems broken below 1.3 m were measured at break point, and notes were taken. For palms smaller than 2 m the bole diameter was measured at plant mid-height (monocot stems are approximately cylindrical, Brown 1997). Canopy height (bottom to tree crown top) was measured by two persons using an inclinometer and 50-m tape. The species and numbers of tree ‘seedlings’ (defined as woody dicotyledonous species with a DBH <2.5 cm, respectively smaller than 1.3 m) were recorded within five 2 m × 2 m sub-plots, four located in the corners of the main plot and one at its center.

Using a digital camera, images were taken of the leaves, twigs, and bark of any species which were unknown, and leaf samples were collected using a plant press. The field images and collected material were then compared to herbarium specimens at Huế University of Agriculture and Forestry (HUAF) and/or the Consultative and Research Center on Natural Resource Management (CORENARM) in Huế City, and were compared with descriptions in the literature (i.e. Ho 1999; FIPI 1996; Henderson 2009; Flora of China 2015). Species which could still not be identified were numbered A, B, C, etc. Taxonomy followed Flora of China (2015) and Tropicos (2015), i.e. the most recently updated sources.

Vegetation parameters derived from field data

A full list of recorded species, including summary statistics and additional information, is provided in Additional file 2: Tables S1 and S2. This includes (in footnotes) detailed descriptions of calculation methods (including allometric formulae) used to summarize the plant species data. MS Excel was used for calculations.

For all plots we calculated the tree densities (extrapolated to counts per hectare) and total tree basal areas (TBA in m2∙ha–1; Bonham 2013), and the mean and maximum tree DBHs and canopy heights. Above-ground dry-matter woody biomass of dicotyledonous trees (eAGBd in kg) was estimated using an allometric formula provided by Chave et al. (2005) and data on tree species’ wood densities provided by Zanne et al. (2009). The eAGBp of palms was estimated using a formula by Goodman et al. (2013), setting wood density at 0.37 g∙cm–3. The summed-up eAGBs of all trees per plot were then extrapolated to total above-ground woody biomass (TeAGB in Mg) per hectare.

The importance value index (IVI) was calculated for each tree species by summing up the species’ relative density, frequency and dominance (Curtis and McIntosh 1951); IVI served for overall ranking (IVIR) of the species’ importance. To describe plant species diversity on plots biodiversity indices (i.e. Shannon Index H′, Shannon Evenness J′, inverse Simpson’s Index 1/D) were calculated using formulae provided by Magurran (2007).

Physical and biological plot data recorded during the survey

Plot UTM coordinates and elevations were recorded using a hand-held GPS receiver (Garmin 12XL, GARMIN International Inc., Kansas City). Slope inclinations of plots were determined using an inclinometer and a 50-m tape. Using a gouge auger five random 40-cm-deep soil samples were taken in each of the five sub-plots; the 25 samples were mixed to be representative for one main plot. The samples were weighted in the field and after being oven-dried at HUAF, whereby relative weight differences provided indications of soil moisture on plots at respective times of sampling (termed ‘soil field capacity index’, FCI). The samples were then brought to the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT, Bangkok) for further analyses of soil pH (by pH meter), color and nutrients. Dried pestled soil samples were photographed (using a flash), and the RGB (red, green, blue) chromaticity values were determined from digital images using Adobe Photoshop. Soil organic matter (OM) was determined through weight loss on ignition, and total nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) were determined using the Kjeldahl method (Bremner 1960; Nelson and Sommers 1996).

Data analyses and assessments

Minitab 15 (Minitab Inc., State College, Pennsylvania), MS Excel and R software were used for calculations and statistical analyses. A vegetation classification was first performed on species’ biomass data (respective TeAGB plot data, transformed to normal distribution) by using dendrograms. Manhattan distance measure and Ward linkage method provided a dendrogram with distinct vegetation classes; these classes could also be pertinently explained from plot distributions within the hilly terrain (Fig. 3). Based on this classification a species association table was composed (following Kent 2012), illustrating floristic differences among vegetation types. The complete table is represented in Additional file 1: Table S1, whereas a sub-set of the sixty most important species (in terms of IVI) is shown in Table 2. More detailed information on the thirty most important species (and another four species of interest) is provided in Table 3. Species rank/abundance diagrams and rarefaction curves (including real data and corresponding models from log-logistic regressions) are shown in Fig. 5; these illustrate patterns of tree species richness overall and within the two main vegetation types. Summary information of various parameters (relating to vegetation structure and diversity, terrain and soils) is provided in Table 4. This Table also provides information (obtained from FIPI 1996; Ho 1999; Wiart 2003; Tanaka and Nguyen 2007; Henderson 2009; Flora of China 2015; Fern et al. 2016) on the recorded tree species’ utility (value categories: ‘no’ [0], ‘moderate’ [1], ‘good’ [2], ‘excellent’ [3] or ‘unknown’ [-]) of timber and non-timber forest products (NTFP; utility of fire wood was not assessed). Simple T-tests were used to assess differences of parameters (transformed to normal distribution) between the two main vegetation types (Table 4). In addition, in order to illustrate vegetation distributional patterns in relation to bio-physical gradients (in terrain, soil parameters, biomass and stocking density; Fig. 4) a canonical correspondence analysis was performed on the thirty most important species (accounting for 69% of TeAGB, Table 3).

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) plot, showing the correspondence (~influence) of main environmental factors (blue arrows; cf. Table 4) with the vegetation composition of the plots (black crosses; vegetation types R1, R2, B1 and B2 of the plots are indicated). The analysis was based on the 30 most important trees species (each one shown as a red dot). The analysis was significant overall at p < 0.001 (permutation test for CCA). The eigengrad values of the environmental variables (providing a measure of importance of each variable to explain gradients in vegetation patterns, listed from the strongest to the weakest) were 0.119 for ‘elevation’, 0.109 for ‘creek’, 0.069 for ‘tree density’, 0.054 for ‘slope’, 0.038 for ‘dead trees (%)’, 0.035 for ‘soil OM’, 0.034 for ‘dead TeAGB (%)’, 0.031 for ‘sapling density’, 0.029 for ‘TeAGB’, 0.029 for ‘soil pH’, 0.027 for ‘soil N’, and 0.022 for ‘soil water’

Results

Tree species diversity and floristic-structural forest patterns

In total 170 species of 88 genera and 45 plant families were recorded in a sample of 2,384 trees (of which 27.6% were ‘sapling’ sized) in the survey (on 1.6 ha). In addition, two rattan species were only recorded at ‘seedling’ size. Most species (128) could be clearly identified, but 32 were identified only to genus, and 12 rare species remained unknown. The most important plant families by tree count were the Arecaceae (representing 15% of all trees/shrubs; 15 species), Euphorbiaceae (7%; 15 spp.), Fagaceae (7%; 5 spp.), Burseraceae (7%; 5 spp.), Myristicaceae (6%; 3 spp.), Moraceae (6%; 9 spp.), Cannabaceae (5%; 2 spp.), Lauraceae (5%; 18 spp.), Myrtaceae (5%; 4 spp.), Sapotaceae (4%; 4 spp.), Sapindaceae (4%; 7 spp.), and Rubiaceae (3%; 3 spp.).

A majority of identified species (44%; including dominant species), had a predominantly southward-tropical distribution, but many species (36%) were distributed within the Sino-Himalayan mountain regions or were regional endemics (within the Trường Sơn Ranges; 18%) (Table 1). A large majority of species was rare; rank/abundance patterns did not differ substantially among different tree size strata (Fig. 4). No species was recorded on all plots, but several common species were found more or less throughout HPC-forest (Tables 2 and 3). Trees with a DBH ≥10 cm were represented by 129 species (i.e. 75%). Calculations using log-logistic models (Fig. 4) indicated that on average ~70.2 ‘large’ tree species (DBH ≥10 cm) and an additional ~23.4 smaller-sized species may be found on one contiguous hectare.

Despite significant overlaps of species distributions, vegetation dendrograms revealed two relatively clearly distinguishable forest types that were mostly related to terrain (Figs. 3 and 4, Table 2). One type, referred to as ‘hillside ridge’ (R) forest (represented by 20 plots), was mostly distributed at higher elevations (Table 4, Fig. 4). This R-type could be further split into sub-types R1 (12 plots) and R2 (8 plots). R1-plots were mostly found on higher-lying eastern and southern hill ridges (west-/southwest-facing slopes); R2-plots were mostly located at mid-elevation on northern ridges (northwest-facing slopes). Another type, termed ‘hill bottom’ (B) forest (20 plots), was found mostly at lower elevations. It could be split into sub-type B1 (10 plots), predominantly located on moist (soil pH 6.5 ± 0.3) and mild slopes (mean inclination 43° ± 18°), and B2 (10 plots), commonly on steeper (63° ± 9°) wet slopes close to creeks (soil pH 6.9 ± 0.2) (Fig. 4). Further divisions into vegetation sub-types were possible (Fig. 3, Table 2).

The vegetation types were determined by species distributions (Tables 1 and 3; cf. Discussion Section); no distributional gradients within the vegetation were discernible in regards to entire plant families (Additional file 2: Table S1). Compared to R-forest, B-forest was characterized by significantly lower densities of trees, saplings and seedlings. Correspondingly, various tree growth parameters (mean DBH and height, maximum height, TBA, dead biomass) differed between R- and B-forest (Table 4, Fig. 4). Soil N and herbal ground cover were slightly higher in B-forest, but other soil parameters did not differ significantly (Table 4).

Tree species richness was significantly higher in R-forest as compared to B-forest. Model calculations indicated that around 99.0 tree species (thereof ~70.2 with DBH ≥ 10 cm) and 84.4 species (~62.9 with DBH ≥ 10 cm) would be found on average on one contiguous hectare of R- and B-forest, respectively (Fig. 5b). Correspondingly, plot-level species richness as well as Shannon and (marginally) Simpson diversity indices were higher in R- forest as compared to B-forest (Table 4).

Patterns of species richness and diversity within HPC forest. (a) depicts species rank/abundance curves (abundance data in log-normal scale) for species observed at all tree sizes as well as in different size categories (in terms of ‘estimated above-ground biomass’ eAGB). (b) depicts species rarefaction curves (for the entire forest, and for R- and B-forest separately) from plot data (large dots, averages of 12 resamplings) as well as overall fitted log-logistic models, adjusted for spatial inter-plot distance to represent species increase with contiguous area (models were based on plot data but plot-to-plot steps were lowered by a factor of 0.56 as determined via comparison to plot-scale species rarefaction models in Additional file 1: Figure S2)

Utilities and conservation values of forest tree species as inferred from literature

Of the trees (DBH ≥6 cm) present on plots 35% were in harvestable timber range with a DBH of ≥15 cm, and 8% with DBH ≥30 cm (Fig. 6). Among the 172 woody species recorded 12 species (7%) were assessed to provide timber of ‘excellent’ value, 32 (19%) of fairly ‘good’, 44 (25%) of ‘moderate’, 41 (24%) of ‘insignificant’ (or undescribed), and 43 (25%) of unknown value. Only 4.7% of the biomass (TeAGB) stock on the plots was in ‘excellent’ harvestable timbers. The biomass of ‘good’ timber was slightly higher in B-forest compared to R-forest (Table 4). In between 2010 and 2015 larger portions of B-forest (70% of plots) were converted to acacia as compared to R-forest (45%; Tables 1 and 4), but cut and non-cut plots did not differ significantly in terms of TeAGB of ‘excellent’ and/or ‘good’ timber.

Most identified species were known to provide some potentially useful non-timber forest products (NTFPs) ranging from edible fruits and nuts, saps used for medicine, to materials (e.g. rattan rods, dies, leaves) useful for handicrafts (Table 3). Eight species (5%) could provide NTFPs assessed as ‘excellent’ value, 35 species (20%) of ‘good’, 41 (24%) of ‘moderate’, 43 (25%) of ‘insignificant’ (or undescribed), and 45 (26%) of unknown value. The TeAGB of tree species providing ‘excellent’ NTFPs was relatively high (14.7%). Compared to R-forest, B-forest was characterized by higher ratios of trees (in terms of TeAGB) providing ‘excellent’ NTFPs, and lower ratios of trees with ‘moderate’ NTFPs, but due to high variability among plots the differences between vegetation types were only marginally significant (Table 4). The plots which were cut in between 2010 and 2015 were, however, characterized by a significantly (T-Test: t = 2.96, p = 0.005) higher biomass ratio (20.0% ± 16.0%) of ‘excellent’ NTFP species compared to the non-cut plots (7.4% ± 8.4%) (other differences being insignificant).

Discussion

Examining the ‘natural history’ and ecology of tree species diversity within HPC-forest

Species richness in Indochinese rainforests, and especially from Yunnan southward along the Trường Sơn Range, is very high, with up to ~200 woody species per ha recorded in southern Yunnan (Lü and Tang 2010). Often >100 tree species (with DBH ≥10 cm) per ha are found, but at this scale of assessment the region’s diversity cannot compare to the most diverse forests in South America and insular Southeast Asia where often >250 species∙ha–1 are recorded (Wikramanayake et al. 2002; Corlett and Primack 2011; Corlett 2014). HPC-forest has been significantly disturbed and modified by human activities. Nonetheless, with an estimated average of ~70 tree species (DBH ≥10 cm) per contiguous hectare, the forest contained about 1.0–3.0 times as many species as were found on comparably-sized and often better-protected sites of evergreen broadleaf forests in locations in Northern Vietnam, 0.7–1.8 times the species recorded on plots in the Central Coast, 0.8–2.0 times species richness in the Central Highlands and in Southern Vietnam, and 0.7–2.7 times the richness in southern tropical Yunnan, China (Cao and Zhang 1997; Blanc et al. 2000; Wode 2000; Tran et al. 2013a; 2010a; 2015; Corlett 2014; Thinh et al. 2015). At slightly higher elevations (280–380 m a.s.l.; Fig. 1) maximally 48 species∙ha–1 were recorded by Ha (2015) in Bạch Mã National Park. Even though species such as Gironniera subaequalis, Palaquium annamense and Scaphium macropodum were abundant in both studies, only 26 of 63 species recorded by Ha (2015) were also found in HPC-forest. This points at appreciable changes in floristic composition along relatively short spatial gradients - as was itself observable within HPC-forest (Table 2).

The floristic composition and associated structure of HPC-forest is an outcome of inherent longer-term (evolutionary/biogeographic) and shorter-term (ecological/anthropogenic) processes. The composition largely reflects the region’s intersection of southern wet-tropical (Southern Indochinese, Malesian) and more northern sub-tropical mountain-associated (Sino-Himalayan, Indo-Burmese) floras (Wikramanayake et al. 2002; Averyanov et al. 2003). Like in other parts of Southeast Asia (Ashton 2003; Culmsee et al. 2011; Culmsee and Leuschner 2013) the vegetation in the montane and sub-montane parts of the Trường Sơn Ranges is characterized by species from plant families of temperate northern origin, and partly of southern or Ancient Asian origin (Rundel 1999; Kuznetsov and Guigue 2000; Averyanov et al. 2003; Sterling et al. 2006; Huynh et al. 2016). In HPC-forest, tree species with a mostly submontane-colline distribution (Castanopsis sp., Syzygium spp., Cinnamomum spp., Canarium album, Cratoxylum pruniflorum, Illicium griffithii, Engelhardtia spicata, Melicope pteleifolia, Breynia fruticosa, Artocarpus styracifolius) were common along the higher-lying ridges of the hill (R-forest), and especially on the hill top (R1t). In contrast, species with a wide distribution in Southeast Asian (including Malesia) wet-tropical lowland forests (e.g. Gironniera subaequalis, Artocarpus rigidus, Morinda citrifolia, Garuga pinnata, Knema globularia, Litsea glutinosa, Schefflera octophylla, Pometia pinnata, Elaeocarpus griffithii, Plectocomia elongata, Mimusops elengi) were mostly either distributed throughout the forest or on more moist plots on lower slopes at the hill bottom (B-forest) (Tables 2 and 3).

In addition to many widely-distributed species, a strong endemic Vietnamese-Laotian (Annamite) floristic component was recognizable (Table 1). Several important tree species (e.g. Palaquium annamense, Schefflera violea, Wrightia annamensis, Hopea pierrei, Madhuca pasquieri) were Vietnamese endemic representatives of widespread tropical genera. Thừa Thiên-Huế and adjacent provinces are a hotspot of palm diversity and endemism (Henderson 2009), and 40% of the palm species in HPC-forest were indeed endemics. Some tree and palm species could not be clearly identified due to the absence of distinguishing plant parts. Some of these unidentified species could possibly represent more than one species: for example, in nearby Bạch Mã National Park several species of Castanopsis (16), Syzygium (19) and Ficus (35) have so far been recorded (Huynh et al. 2016). Furthermore, it is not unlikely that some unidentified species represented local endemics not yet described by botanists at the time of the study. For example, the abundant (IVIR 3) Licuala sp. was possibly the only recently described Licuala dakrongensis (Henderson et al. 2010), and Hopea sp. was perhaps Hopea vietnamensis (Hoang et al. 2013). The taxonomy of several species is still contested. For example, Knema globularia was listed in other sources (FIPI 1996; Ha 2015; Flora of China 2015; Huynh et al. 2016) as either K. corticosa, K. conferta or K. tonkinensis. Following closer genetic analyses new ‘cryptic’ species may be discovered among the long list of currently described taxa (Bickford et al. 2006).

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the high diversity and endemism (respectively ‘pseudo-endemism’, Turvey et al. 2016) in forests along the Trường Sơn Ranges (Wikramanayake et al. 2002; Sterling et al. 2006). The floristic composition of Indochina is partly a result of ancient plate tectonic collisions, and resulting terrains and associated local climates (Hua 2013; Corlett 2014). More recent processes during the climatically variable quaternary period, however, appear most important to explain today’s biogeographic patterns; such processes include sea level changes, cool/dry periods when forests retreated and were isolated, and climatic shifts along elevational gradients (Woodruff 2010). Evidence suggests that the Trường Sơn Ranges served as a refugium for wet-tropical forest species during cool/dry periods in the quaternary, but the region was itself also a center of species diversification (Sterling and Hurley 2005; Sterling et al. 2006; Corlett 2014). The ‘refugium hypothesis’ is supported by the fact that some species found in lowland Central Vietnam (e.g. Knema pierrei, Elaeocarpus apiculatus, Ficus glandulifera in HPC-forest) also occur in Peninsular Malaysia but are not found in lowland forests in between.

High species richness reflects the many rare species in HPC-forest. Numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain co-existence of many tree species within a small forest area; these mostly consider the range of ecological niches available along small environmental gradients and the spatial impacts (often density-dependent) of a vast diversity of pests and diseases (often host-specific) at different plant life stages (Wright 2002; Freckleton and Lewis 2006; Ashton 2014). Within HPC-forest, species’ habitat descriptions from the literature largely fitted their distributions, with many species described as typically occurring on hill slopes and/or on humid soils (Table 3; Additional file 2: Table S2). The boundaries of vegetation types were however blurry (Table 2). In accordance with findings of other regional studies (Potts et al. 2002; Cannon and Leighton 2004; Noguchi et al. 2007; Du et al. 2013), this suggests that tree species distributions were strongly influenced by a mixture of relatively stochastic (e.g. propagule dispersal, forest disturbance) and more deterministic (e.g. factors relating to habitat) processes across environmental gradients (in HPC-forest largely governed by elevation and terrain, and corresponding soils; Fig. 4). In a study by Nguyen et al. (2016) in nearby A Lươi District 16 out of the 18 most abundant species on a two-hectare study plot (elevation 625–660 m a.s.l.) showed an aggregated distribution in the range of up to 15 m. Furthermore, many significant spatial associations were observed between different tree species. The authors mainly interpreted the patterns as evidence for the species’ dispersal limitations and inter-specific processes of herd protection and/or facilitation. Patterns within the ‘late successional’ forest were, however, barely discussed in regards to micro-topography, soils and potential earlier disturbances. In HPC-forest anthropogenic disturbances in the vegetation were fairly evident.

Anthropogenic influences on forest composition and natural processes

One can only guess what HPC-forest may have looked like before the influence of humans. The forest probably contained many more upper-canopy (20–30 m) and emergent (up to >40 m) trees of ‘excellent’ (hardwood) timber quality, e.g. dipterocarps (Hopea and Parashorea spp.), legumes (Erythrophloeum fordii, Sindora and Peltophorum spp.), and representatives of other plant families (Madhuca pasquieri, Mimusops elengi, Tarrietia javanica, Elaeocarpus spp.). These species (except E. fordii) were still found in HPC-forest, however at low numbers (0.6–6.3 trees∙ha–1) and small sizes (Additional file 2: Table S1). The only common species with ‘excellent’ timber quality was a slow-growing undergrowth tree (Melanorrhoea laccifera, IVIR 17). Due to its small timber volume it was probably not a target during SFE logging operations; in addition, it was characterised by good regeneration (Tables 2 and 3). In a study in three communes in Nam Đông District (Ngo and Webb 2008; 2016), several excellent timber species (in particular Hopea pierrei, Parashorea stellata, E. fordii, M. pasquieri and Sindora tonkinensis) were mentioned by villagers as species indicating ‘relatively intact forest’. Only H. pierrei and M. pasquieri were however found on field plots, which supports the presumption that the forests have significantly changed due to selective logging.

Logging-out of high-value timber was probably most severe during the 1970s to late 1980s, and some selective extraction by villagers or ‘wood poachers’ may have continued thereafter. Nonetheless, in 2010 the overall per-hectare standing biomass (TeAGB) of harvestable timber (DBH ≥15 cm) was sizeable, with 96 Mg (equivalent to 169 m3) in B-forest and 109 Mg (~212 m3) in R-forest. Per-hectare timber stock of larger trees (DBH ≥30 cm) was 56 Mg (~101 m3) in B-forest and 61 Mg (~125 m3) in R-forest. HPC-forest would thus be classified in Vietnam mostly within the range of ‘average’ forest (100–200 m3∙ha–1). This is however still markedly lower than primary rainforests which can reach harvestable timber stocks of considerably more than 300 m3∙ha–1 (‘very rich’ forest; MARD 2009), with above-ground biomass exceeding 350 Mg∙ha–1 (Hai et al. 2005, and literature cited therein).

Relatively large trees of species with lesser timber quality were found on many plots in the forest (Table 3). Gironniera subaequalis and Artocarpus rigidus (IVIR 1 and 2; with ‘good’ timber quality) were reportedly not a main target for logging by SFEs, but are occasionally used by villagers for house building and furniture (D.T. Ngo, pers. comm.). These species’ high abundance appeared to be partly explained by their dispersal and recruitment capacity under canopy shade (300–2050 seedlings per ha), and associated persistence during and after selective logging operations (including coppicing in the case of G. subaequalis, and tenacity in steep terrain in the case of A. rigidus; Tables 2 and 3; Raich and Khoon 1990; Ding et al. 2012). A. rigidus was possibly also promoted by local villagers because of the tree’s valued sweet fruits and timber (Wetterwald 2003; Lim 2012). In contrast, the success of G. subaequalis may be explained by ecological competitiveness under post-logging conditions. G. subaequalis has the capacity to enrich available N in its tissues (roots and leaves) and use it to produce acid phosphatase to efficiently exploit the more limited levels of available soil P – possibly at the expense of other trees which cannot compete for P in its presence (Huang et al. 2013).

Ngo and Webb (2008, 2016) listed G. subaequalis, Palaquium annamense, Syzygium spp. and Canarium album as indicators of ‘relatively intact forest’, whereas A. rigidus and other species (including Horsfieldia amygdalina, Garcinia cochinchinensis, Knema pierrei, Castanopsis spp., Pometia spp., Gonocaryum maclurei) were rather associated with ‘selectively logged forest’. Yet, prime indicators of impacted forest are probably species that do not regenerate under canopy shade. Such species include Garuga pinnata, Lithocarpus amygdalifolius, H. amygdalina and possibly Syzygium jambos – species which in HPC-forest were common in the upper tree size strata but lacked representation by seedlings (Table 3). G. pinnata and H. amygdalina were possibly dispersed by birds into forest gaps and may have profited from the aftermath of logging, but L. amygdalifolius and S. jambos (both with ‘good’ timber qualities and presumably more locally dispersed propagules) were probably mainly promoted after logging via active seeding/planting by villagers. The fact that these species were primarily found in B-forest (and sub-types R1t and R1b; Table 2) suggests that this was indeed the most heavily impacted part of the forest. The elevated herbal ground cover, lower seedling and sapling densities, higher tree mortality and associated lower tree density, and lower species richness and diversity were further indications that B-forest had been more disturbed than R-forest, including effects such as compaction and erosion of soils (Table 4, Fig. 4; Sidle et al. 2006; Clarke and Walsh 2006; Chazdon 2014). Wood collection by villagers and other on-going impacts in better-accessible B-forest may also partly explain the low sapling densities (Hoang et al. 2011; Popradit et al. 2015).

The ‘restoration history’ of HPC-forest is not known in detail. In Vietnam, Thailand and other tropical countries various species of Lithocarpus, Castanopsis, Syzygium, Artocarpus, Ficus, Cinnamomum, Horsfieldia, Garuga, Canarium and Garcinia have, however, been used for more or less successful direct seeding of degraded forests (Woods and Elliott 2004; Cole et al. 2011; Tunjai 2012) and/or as framework trees for forest restoration (Blakesley et al. 2002; Elliott et al. 2003; Khopai and Elliot 2003; FSIV 2003; Acharya and Kafle 2009). Various species of these and other genera (some with capacity to coppice; Table 3) were most probably also promoted in HPC-forest by villagers during initiatives to upgrade and ‘enrich’ local logged-out forests, whereby species selection/promotion was a mixture of practical ecological considerations (what can grow readily under specific conditions?) and the potential prospective utility of planted trees (van Kuijk 2008; next Section). Human influences thereby interacted with natural processes. In a study by Khopai and Elliot (2003) in Northern Thailand G. pinnata, Glochidion eriocarpum and species of the genera Artocarpus, Ficus, Litsea, Antidesma, Dillenia, Castanopsis, Scaphium and Cratoxylum were readily dispersed by animals to forest restoration sites where framework species had previously been planted.

NTFPs and associated values of HPC-forest

The potential utility of many species for NTFPs (in addition to timber) largely explained their presence and/or relative abundance within HPC-forest. Native species which were valued for food (fruits, nuts or seeds) were cultivated and/or promoted by local villagers since time immemorial, and were additionally favoured during government-sponsored forest restoration activities in the 1980s and 1990s. Amongst the thirty most important species were the highly valued fruit tree species Morinda citrifolia (Indian mulberry or noni), Garcinia cochinchinensis (false mangosteen), Scaphium macropodum (Vietnamese malva nut), Syzygium jambos (Malabar plum), Artocarpus rigidus (monkey jackfruit), Canarium album (Chinese olive), Litsea glutinosa (Indian laurel), and Pometia pinnata (island lychee) (Table 3). The three non-native species found in HPC-forest were economically valuable either for fruits (Morus alba - white mulberry, native to China; fairly common, IVIR 35; Nephelium lappaceum - rambutan, native to Malesia; one tree recorded) or camphor wax (Cinnamomum camphora - camphor laurel, native to Taiwan; two trees). The presence of valuable trees does obviously not entail that nearby communities actually collected and used all potentially available NTFPs, nor that they still tended the tree resources in sustainable ways. For example, malva nut trees (S. macropodum; IVIR 18, with highest woody biomass; Table 3), often appeared to be damaged, presumably because the nuts were harvested by cutting entire branches (YT Van, pers. obs.; Huy 2012).

Earlier data from Wetterwald (2003, 2004) gathered in Katu communities in Nam Đông indicated that for 14% of households collection of NTFPs was a mainstay for their livelihoods, 48% collected NTFPs part-time, whereas 38% occasionally or never collected NTFPs. More than half of the households interviewed (mostly those engaged in collecting) traded with NTFPs, whereby the commercially most valuable plant products (besides honey and mushrooms) were cane and baskets from rattans, bamboo shoots, malva nuts and other fruits (e.g. rambutan and rainforest figs), and bark from Litsea spp. (used for incense and medicine). On the plots in HPC-forest no bamboo species and none of the traded rattan species listed by Wetterwald (2003), McElwee (2010) or Polesny et al. (2014) were recorded. The most valued rattan species found in HPC-forest (i.e. Calamus nambariensis and C. rhabdocladus; Henderson 2009) were also the rarest (one seedling each; IVIR 171 and 172). Analogous to valuable timber species, important NTFP which were harvested as whole plants (or substantial plant parts) were therefore largely depleted in HPC-forest. Correspondingly, respondents in a study by Tran et al. (2010b) reported that availability of tradeable NTFPs has markedly declined in Nam Đông during the preceding decade (associated incomes have about halved), except for ‘broom grass’ (Thysanolaema maxima) which prolifically grows in gaps created in forests. Over-exploitation of rattan has become a major problem in the buffer zones of Bạch Mã National Park where new schemes for participative forest protection and resource monitoring have recently been initiated (Ha et al. 2016).

The vanishing of many commercially valuable wild species coincides with changes in local people’s livelihoods and socio-economic interactions during the past two decades. Soon after forest land allocation (FLA) during 1999-2005, home gardens and orchards were expanded and planted with fruit trees (from Artocarpus to Nephelium spp.) and acacia woodlots (for fuel and timber); these covered many household needs and diminished dependencies on fluctuating or declining forest resources (Wetterwald et al. 2004; Tran et al. 2013b). Cash income from expanding larger-scale commercial acacia plantations has become ever more important, however with an income gap opening between rich landholders (making good profits from acacias) and poor households (becoming more marginalized and dependent on casual/subsidiary labor) (Tran et al. 2013b; Bayrak et al. 2015). In accordance with expanding cash crops, the collection of wild products has also become more commercialized, with rich households often maintaining controls over collection/trade of key products (McElwee 2008; Sikor and To 2011; Tran et al. 2013b). Programs of community-based forest management (CFM) were launched in 2006 and piloted in Nam Đông (Tran et al. 2010b), but strong socio-economic dynamics linked to market forces and emerging cash crops outweigh many efforts directed at the conservation and sustainable use of remaining communally managed natural forests. Households in Nam Đông now increasingly use alternative materials to forest products, such as concrete and plastic for house construction, synthetic medicines instead of medicinal plants, and gas for fuel (Tran et al. 2013b). Fewer and fewer people know about traditional forest products, especially the vast diversity of medicinal plants, i.e. 432+ species that were formerly collected in forests around Bạch Mã National Park (Tran and Ziegler 2001; Tran et al. 2013b).

Losing economic value, losing ground: considerations on forest biodiversity conservation

The decreasing appreciation and use of traditional forest products relative to highly-priced merchandises (acacia wood, rubber, meat products) largely explains the demise of natural forests in the lowlands. Today virtually no rainforests remain in the plains and low-lying hills (below ~200 m elevation) in between Nam Đông and the coast, and acacia plantations continue to encroach into rainforest areas in colline and sub-montane rim-zones (Cochard et al. 2017). It is not unlikely that some specialized endemic lowland species have already become extinct. Within the ‘Northern Vietnam Lowland Rain Forests Ecoregion’ few forests remain (almost all affected by logging) in nine small protected areas and numerous fragments. Most of these forests have not been scientifically surveyed. The protected areas (covering ~3.9% of the ecoregion) barely embrace the entire ecoregion’s high biodiversity and endemism; hence, any remaining forest fragments – whatever their small size – are likely of considerable conservation value (Wikramanayake et al. 2002; McElwee 2016).

While extensive intact forestlands are needed to safeguard key biodiversity of rainforest ecosystems, considerable numbers of endangered plant and animal species (especially smaller species) can persist in forest fragments for decades (Turner and Corlett 1996; Hernández-Ruedas et al. 2014). Forest fragments can be important refugia for economically valuable species, and provide a biological store and nucleus from where forest regeneration of surrounding areas can be re-seeded under favorable conditions (Chazdon 2014; Sloan et al. 2016). Besides the presence of little known or even undescribed species, several species found in HPC-forest were listed in the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2016) or the Vietnam Red Data Book (2007) as ‘endangered’ (Hopea pierrei, Sindora tonkinensis, Tarrietia javanica) or ‘vulnerable’ (Knema pierrei, Mangifera minutiofolia, Elaeocarpus apiculatus, Madhuca pasquieri). This underlines the potential of the remaining forest fragments to maintain threatened species, especially species restricted to lowland forests.

To what degree (and in what ways) forest fragments can maintain assemblages of historically occurring species depends on many factors. Fragments only retain a ‘sample’ of the species present within the original non-fragmented forest, and the maximum number of species is related to fragment size (Laurance et al. 2011). For HPC-forest the extrapolative application of the log-logistic model equation (Fig. 5b) indicated that in total perhaps 255 tree species would have been found in the entire HPC-forest fragment (76 ha) in 2010. From simple loss of area this number would have decreased to ~237 species in 2014 (46 ha) and ~231 species in 2015 (39 ha). In contrast, ~319 species were possibly present in the larger connected forest in 2003 (742 ha) and ~287 species may still be found in the total forest area remaining in 2015 (203 ha, including another larger fragment; Additional file 1: Figure S1). The calculations suggest that species losses may be moderate (–28%, 2003–2016) relative to the substantial (–95%) decrease in area (considering HPC-forest alone). Calculations focusing on area alone, however, disregard potential longer-term impacts of fragmentation. Deforestation and reduction of HPC-forest has occurred over a period of just a few years. Hence, in 2010 many slow fragmentation-associated degradation processes were not yet distinguishable from effects associated with other impacts (logging, forest uses). Fragmentation effects will however become more obvious – provided the remaining fragment actually persists.

Tree communities in forest fragments that are initially diverse may biologically simplify as a result of isolation and reduced populations of many species. Given that pollinators may become functionally extinct within the fragment (Brosi et al. 2008) and can often not traverse the surrounding matrix (Kormann et al. 2016), rare plant species may eventually disappear from the fragment due to failing pollination and/or inbreeding. Ha (2015), for example, found that allelic diversity of seedlings of the dipterocarp Parashorea stellata was significantly reduced in forest fragments as compared to seedlings in contiguous forest in Nam Đông - despite observed inter-fragment genetic exchange. In several studies (e.g. Lopes et al. 2009; Breed et al. 2012; Zambrano and Salguero-Gómez 2014; Lowe et al. 2015 and studies cited therein) lowered tree fecundity was important to explain differences in tree seedling establishment between fragments and contiguous rainforest. In HPC-forest a majority of species was rare (Fig. 5a). In the fragment remaining in 2016 (39 ha) species recorded by three (9% of all species), two (14%) or merely one tree (25%) may in the fragment on average be represented by 73, 49, or 24 trees, respectively. Seedlings were recorded for only 14% of these rare tree species, and seedling frequencies of species with 1–5 trees∙ha–1 were on average (3.5 seedlings/tree) almost three times lower than for species with more trees (10.1 seedlings/tree). This indicates that there was an on-going fragmentation-related trend towards losses of certain rare species.

Introductions of seeds from outside the fragment may keep small tree populations viable and/or change the species composition in the fragment. The most important seed dispersal agents in Indochinese rainforests are birds; accordingly, fruit sizes of many rainforest trees are relatively small (Corlett 2014; Table 3). In HPC-forest some common passerines such as babblers, thrushes and white-eyes were observed, and these may have brought in seeds from species such as Melicope pteleifolia, Glochidion eriocarpum, Eurycoma longifolia, Knema pierrei and Schefflera octophylla which were represented by widely-scattered seedlings (Tables 2 and 3; Datta and Rawatt 2008; Snow 1981; Kitamura et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2010). Tree species with larger fruits (>25 mm diameter), such as Pometia spp., Garcinia cochinchinensis, Artocarpus rigidus, Dillenia scabrella, Gonocaryum maclurei and palms were more likely dispersed by civets and/or rodents (especially squirrels), and probably just within the fragment (Kitamura et al. 2002; Corlett 2014). Species with winged seeds (Cratoxylum pruniflorum and Tarrieta javanica, but probably not dipterocarps; Au et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2015) may also be partly sourced from far-away areas by wind (Table 2). No connected lower-lying forests persisted near HPC-forest; the nearest contiguous forest (1.5 km east of HPC-forest) ranged from 300–1,100 m elevation. Hence, while many remaining lowland species within HPC-forest were presumably about to decline, there was possibly an increasingly higher colonization chance by more generalist-montane species. Several species recorded in HPC-forest (120–330 m elevation) had an altitude distribution range up to well over 1,000 m, and according to the literature some bird-dispersed species (e.g. Disepalum plagioneurum, several Litsea spp., Archidendron clypearia, Turpinia cochinchinensis, Eurya nitida; Kitamura et al. 2002) would not be expected below ~500 m.

Data described by Ha (2015) from older forest fragments (estimated 30 years since fragmentation) in Nam Đông indicated that tree species richness in fragments larger than 50 ha was not different to the richness within comparable contiguous forest (~40-48 species∙ha–1), but smaller fragments were relatively impoverished (i.e. 28–32 species∙ha–1 in 10-23 ha-sized fragments, and 14–21 species∙ha–1 in 1–5 ha fragments). Ha (2015) attributed this mostly to fragment edge-effects such as lowered humidity, higher temperatures, and increased light and wind – i.e. effects which may increase mortality of sensitive trees and seedlings, and simplify the vegetation by promoting generalist species (Laurance 1997; Benitez-Malvido and Martínez-Ramos 2003; Bennet and Saunders 2010; Cochard 2011). Edge-effects in small fragments are disproportionally higher than in large fragments; simultaneously, anthropogenic impacts may increase in smaller fragments (Arroyo-Rodríguez et al. 2015).

In 2010 the plots were still located well inside HPC-forest, and edge-effects per se were thus barely obvious. The fragment boundary was, however, pushed back 2010–2015, and more than half of the plots were cut. Clearance was highest in the most accessible lower-lying forest parts; these parts were also relatively rich in harvestable ‘good timber’ (e.g. Lithocarpus amygdalifolius, Scaphium macropodum, Pometia spp. and Syzygium jambos; Tables 2 and 3). The destruction mostly affected the already previously highly impacted and modified B-forest, but also species-rich parts in R2- and R1b-forest (Table 2, Fig. 4). Judging from plot data a large fraction of trees with ‘excellent’ NTFPs was destroyed (77% in terms of TeAGB), including most (91%) of the commercially valuable malva nut trees (S. macropodum). This lends support to the note that the boom of acacia wood production currently outcompetes the economic values of many other commercially tradeable forest products.

Conclusions

Lowland forests in North-Central Vietnam are rich in biodiversity and endemic species, but most of the few remaining forests have been and are being anthropogenically modified. Repeated cycles of selective logging by state forest enterprises (SFEs) and other actors have caused once-dominant tree species to become rare and endangered. Logged-out forests were subsequently ‘enriched’ with economically valuable tree species, especially during forest restoration initiatives. Such impacts and changes were noticeable in the species composition of the studied forest near Hương Phú Commune (HPC). Nonetheless – or perhaps partly because of this – the HPC-forest was characterized by a tree species richness which rivals the diversity found in many better-protected forests in Vietnam.

HPC-forest is one of the last rainforest remnants below ~350 m a.s.l. in Thừa Thiên-Huế Province. Tree species assemblages in this hillside forest were transient between lowland and colline/sub-montane rainforest. As this fragment was connected to a much larger forest only a few years ago, few signs of fragmentation-induced plant community degradation were as yet evident, but rare species (and a few common species) were already disproportionately under-represented by seedlings. Furthermore, on-going extraction of certain types of timber and non-timber forest products (NTFPs, especially rattan) by villagers probably explained the rarity/absence of certain commercially important species. The decreasing value of the forest for villagers (due to resource over-uses and changing economic activities/livelihoods) currently coincides with a boom in industrial plantation forestry. This caused the forest fragment to contract by half its size in between 2010 and 2015. One may expect that HPC-forest will be replaced entirely by plantations within coming years, but it may not yet be too late to safeguard parts of a larger fragment located nearby to the north.

Particularly in view of projected climate change, conservation and management of remaining lowland forests should be strengthened. Under global warming species assemblages are expected to shift upwards in altitude, whereby lowland species will be important to sustain natural forests at mid-altitudes (Colwell et al. 2008; Feeley and Silman 2010). Lower-lying forest fragments should be conserved and possibly connected via corridor strips to nearby protected contiguous forest areas – to facilitate movement of pollinators and seed dispersal agents (Hilty et al. 2006). Conservation programs should be fostered in collaboration with local residents, and may be financially sourced from newly emerging ‘payments for ecosystem services’ (PFES) and/or international funding schemes (Sharma et al. 2016; Thang and Duong 2016). Such programs should contribute to the maintenance/revival of the ethno-botanical cultural heritage; alliance with eco-tourism could generate new incomes for local villagers and help preserve ‘spice-garden’ forests (Joliffe 2014). Inventories and exploration of new medicines from traditional recipes could contribute to developing new marketable products as well as maintain ethno-botanical knowledge (Tran and Ziegler 2001; Hoang et al. 2008), and the safeguarding of natural forests on hillside catchments would help alleviate water shortages (for agricultural irrigation) during dry winter seasons (Tran et al. 2013b; Cochard 2013, 2016). As noted by Woodruff (2010, p. 935) “biogeographers and conservationists must act as if their efforts in the next 20 years will affect the quality of life in this region for at least a thousand years.”

Abbreviations

- AIT:

-

Asian Institute of Technology

- BA:

-

Tree bole basal area (1.3 m above ground)

- CORENARM:

-

Consultative and research center on natural resource management

- DBH:

-

Diameter at breast height (1.3 m above ground)

- GPS:

-

Geographical positioning system

- H’:

-

Shannon diversity index

- HPC-forest:

-

Studied forest fragment near Hương Phú Commune

- HUAF:

-

Huế University of Agriculture and Forestry

- eAGB:

-

Estimated (using allometric formulae) above-ground dry tree woody biomass

- IVI:

-

Importance value index

- IVIR:

-

Importance value index rank

- J’:

-

Shannon Evenness

- N:

-

Total Kjehldahl soil nitrogen

- NTFP:

-

Non-timber forest product

- P:

-

Total Kjehldahl soil phosphorus

- OM:

-

Soil organic matter content (weight loss on ignition)

- RGB values:

-

Red, green, blue soil chromaticity values

- TeAGB:

-

Total estimated dry above-ground woody biomass

- TBA:

-

Total tree basal area

- UTM coordinates:

-

Universal transverse mercator system coordinates

- 1/D:

-

Inverse Simpson diversity index

References

Acharya AK, Kafle N (2009) Land degradation issues in Nepal and its management through agroforestry. J Agr Environ 10:115–123. doi:10.3126/aej.v10i0.2138

Arroyo-Rodríguez V, Melo FPL, Martínez-Ramos M, Bongers F, Chazdon RL, Meave JA, Norden N, Santos BA, Leal IR, Tabarelli M (2015) Multiple successional pathways in human-modified tropical landscapes: new insights from forest succession, forest fragmentation and landscape ecology research. Biol Rev. doi:10.1111/brv.12231.

Ashton PS (2003) Floristic zonation of tree communities on wet tropical mountains revisited. Perspect Plant Ecol 6(1):87–104. doi:10.1078/1433-8319-00044

Ashton P (2014) On the Forests of Tropical Asia. Lest the memory fade. Kew Publishing, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK

Au AYY, Corlett RT, Hau BCH (2005) Seed rain into upland plant communities in Hong Kong, China. Plant Ecol 186(1):13–22. doi:10.1007/s11258-006-9108-5

Averyanov LV, Phan KL, Nguyen TH, Harder DK (2003) Phytogeographic review of Vietnam and adjacent areas of Eastern Indochina. Komarovia 3:1–83

Bayrak MM, Tran NT, Burgers P (2015) Formal and indigenous forest-management systems in Central Vietnam. Implications and challenges for REDD+. In: Cairns MF (ed) Shifting cultivation and environmental change: Indigenous people, agriculture and forest conservation. Routledge, London, pp 319–334

Benitez-Malvido J, Martínez-Ramos M (2003) Impact of forest fragmentation on seedling abundance in a tropical rain forest. Biotropica 35:530–541. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.1998.96295.x

Bennet AF, Saunders DA (2010) Habitat fragmentation and landscape change. In: Sodhi NS, Ehrlich PR (eds) Conservation Biology for All. Oxford University Press, UK, pp 88–106

Bickford D, Lohman DJ, Sodhi NS, Ng PKL, Meier R, Winker K, Ingram KK, Das I (2006) Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 22(3):148–155. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.004

Blakesley D, Elliott S, Kuarak C, Navakitbumrung P, Zangkum S, Anusarnsunthorn V (2002) Propagating framework tree species to restore seasonally dry tropical forest: implications of seasonal seed dispersal and dormancy. Forest Ecol Manage 164:31–38. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00609-0

Blanc LG, Maury L, Pascal JP (2000) Structure, floristic composition and natural regeneration in the forests of Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam: an analysis of the succession trends. J Biogeogr 27:141–157. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00347.x

Bonham CD (2013) Measurements for Terrestrial Vegetation. Wiley-Blackwell, Sussex, UK

Brauer J (2009) War and Nature. The environmental consequences of war in a globalized world. AltaMira Press, Plymouth, UK

Breed MF, Marklund MHK, Ottewell KM, Gardner MG, Harris JBC, Lowe AJ (2012) Pollen diversity matters: revealing the neglected effect of pollen diversity on fitness in fragmented landscapes. Mol Ecol 21(24):5955–5968. doi:10.1111/mec.12056

Bremner JM (1960) Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldhal Method. J Agr Sci 55:11–33. doi:10.1017/S0021859600021572

Brosi BJ, Daily GC, Shih TM, Oviedo F, Durán G (2008) The effects of forest fragmentation on bee communities in tropical countryside. J Appl Ecol 45:773–783. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01412.x

Brown S (1997) Estimating Biomass and Biomass Change of Tropical Forests: a Primer. FAO Forestry Paper - 134. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Rome

Cannon CC, Leighton M (2004) Tree species distributions across five habitats in Bornean rain forest. J Veg Sci 15:257–266. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2004.tb02260.x

Cao M, Zhang J (1997) Tree species diversity of tropical forest vegetation in Xishuangbanna, SW China. Biodivers Conserv 6:995–1006. doi:10.1023/A:1018367630923

Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR (2009) Discoveries of new mammal species and their implications for conservation and ecosystem services. P Natl Acad Sci USA 105:11505–11511. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812419106

Chave J, Andalo C, Brown S, Cairns MA, Chambers JQ, Eamus D, Fölster H, Fromard F, Higuchi N, Kira T, Lescure J-P, Nelson BW, Ogawa H, Puig H, Riéra B, Yamakura T (2005) Tree allometry and improved estimation of carbon stocks and balance in tropical forests. Oecologia 145(1):87–99. doi:10.1007/s00442-005-0100-x

Chazdon RL (2014) Second growth. The promise of tropical forest regeneration in an age of deforestation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Clarke MA, Walsh RPD (2006) Long-term erosion and surface roughness change of rain-forest terrain following selective logging, Danum Valley, Sabah, Malaysia. Catena 68(2-3):109–123. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2006.04.002

Cochard R (2011) Consequences of deforestation and climate change on biodiversity. In: Trisurat Y, Shrestha R, Alkemade R (eds) Land use, climate change and biodiversity modeling: perspectives and applications. IGI Global, Hershey, USA, pp 30–55

Cochard R (2013) Natural hazards mitigation services of carbon-rich ecosystems. In: Lal R, Lorenz K, Hüttl RF, Schneider BU, von Braun J (eds) Ecosystem services and carbon sequestration in the biosphere. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 221–293

Cochard R (2016) Scaling the costs of natural ecosystem degradation and biodiversity losses in Aceh Province, Sumatra. In: Shivakoti G, Pradhan U, Helmi (eds) Redefining diversity and dynamics of natural resources management in Asia. Volume 1: Sustainable natural resources management in dynamic Asia. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 231–271

Cochard R, Ngo DT, Waeber PO, Kull CA (2017) Extent and causes of forest cover changes in Vietnam’s provinces 1993-2013: a review and analysis of official data. Environ Rev (in press). doi:10.1139/er-2016-0050.

Cole RJ, Holl KD, Keene CL, Zahawi RA (2011) Direct seeding of late-successional trees to restore tropical montane forest. For Ecol Manage 261(10):1590–1597. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.06.038

Colwell RK, Brehm G, Cardelus CL, Gilman AC, Longino JT (2008) Global warming, elevational range shifts, and lowland biotic attrition in the wet tropics. Science 322:258–261. doi:10.1126/science.1162547

Corlett RT (2014) The ecology of tropical East Asia. Oxford University Press, UK

Corlett RT, Primack RB (2011) Tropical rain forests. An ecological and biogeographic comparison. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, West Sussex, UK

Culmsee H, Leuschner C (2013) Consistent patterns of elevational change in tree taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity across Malesian mountain forests. J Biogeogr 40:1997–2010. doi:10.1111/jbi.12138

Culmsee H, Pitopang R, Mangopo H, Sabir S (2011) Tree diversity and phytogeographical patterns of tropical high mountain rain forests in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodivers Conserv 20:1103–1123. doi:10.1007/s10531-011-0019-y

Curtis JT, McIntosh RP (1951) An upland forest continuum in the prairie-forest border region of Wisconsin. Ecology 32(3):476–496. doi:10.2307/1931725

Datta A, Rawatt GS (2008) Dispersal modes and spatial patterns of tree species in a tropical forest in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India. Trop Conserv Sci 1(3):163–185, tropicalconservationscience.org

De Koninck R (1999) Deforestation in Vietnam. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada

Dickinson CJ, Thinh VN (2006) An Assessment of the Fauna and Flora of the Green Corridor Forest Landscape, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Report No 7: Green Corridor Project. WWF Greater Mekong & Vietnam Country Programme and Forest Protection Department (FPD), Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

Ding Y, Zang R, Liu S, He F, Letcher SG (2012) Recovery of woody plant diversity in tropical rain forests in southern China after logging and shifting cultivation. Biol Conserv 145:225–233. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.009

Du H, Peng WX, Song TQ, Zeng FP, Wang KL, Song M, Zhang H (2013) Spatial pattern of woody plants and their environmental interpretation in the karst forest of southwest China. Plant Biosyst 149(1):121–130. doi:10.1080/11263504.2013.796019

Elliott S, Navakitbumrung P, Kuarak C, Zangkum S, Anusarnsunthorn V, Blakesley D (2003) Selecting framework tree species for restoring seasonally dry tropical forests in northern Thailand based on field performance. For Ecol Manage 184:177–191. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(03)00211-1

Feeley KJ, Silman MR (2010) Biotic attrition from tropical forests correcting for truncated temperature niches. Glob Change Biol 16:1830–1836. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02085.x

Fern K, Fern A, Morris R (eds) (2016) Useful Tropical Plants Database 2014. http://tropical.theferns.info/.

FIPI (1996) Vietnam forest trees. Forest Inventory and Planning Institute. Agricultural Publishing House, Vietnam

Flora of China (2015). eFloras. http://www.efloras.org/flora_page.aspx?flora_id=2.

Fox J, Dao MT, Rambo AT, Nghiem PT, Le TC, Leisz S (2000) Shifting cultivation: a new old paradigm for managing tropical forests. Bio Sci 50(6):521–528. doi:10.1641/0006-3568v

Freckleton RP, Lewis OT (2006) Pathogens, density dependence and the coexistence of tropical trees. P Roy Soc B 1604:2909–2916. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3660

FSIV (2003) Use of Indigenous Tree Species in Reforestation in Vietnam. Forest Science Institute of Vietnam. Agricultural Publishing House, Hanoi

Goodman RC, Phillips OL, del Castillo TD, Freitas L, Cortese ST, Monteagudo A, Baker TR (2013) Amazon palm biomass and allometry. For Ecol Manage 310:994–1004. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2013.09.045

Ha TNH, de Bruyn LL, Prior J, Kristiansen P (2016) Community participation and harvesting of non-timber forest products in benefit-sharing pilot scheme in Bach Ma National Park, Central Vietnam. Trop Conserv Sci 9(2):877–902

Ha VT (2015) Forest fragmentation in Vietnam: Effects on tree diversity, populations and genetics. Dissertation, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Hai VD, Do TV, Trieu DT, Sato T, Kozan O (2005) Carbon stocks in tropical evergreen broadleaf forests in Central Highland, Vietnam. Int For Rev 17(1):20–29. doi:10.1505/146554815814725086

Henderson A (2009) Palms of Southern Asia. New York Botanical Garden, New York

Henderson A, Ninh KB, Bui VT (2010) New species of Areca, Pinanga, and Licuala (Arecaceae) from Vietnam. Phytotaxa 8:34–40. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.8.1.3

Hernández-Ruedas MA, Arroyo-Rodríguez V, Meave JA, Martínez-Ramos M, Ibarra-Manríquez G, Martínez E, Jamangapé G, Melo FPL, Santos BA (2014) Conserving tropical tree diversity and forest structure: The value of small rainforest patches in moderately-managed landscapes. PLoS ONE 9(6):e98931. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098931

Hilty JA, Lidicker WZ, Merenlender AM (2006) Corridor ecology. The science and practice of linking landscapes for biodiversity conservation. Island Press, Washington

Ho PH (1999) An Illustrated flora in Vietnam. Part I, II, III. Young Publishing House. [in Vietnamese]

Hoang VS, Braas P, Kessler PJA (2008) Traditional medicinal plants in Ben En National Park, Vietnam. Blumea 53:569–601. doi:10.3767/000651908X607521

Hoang VS, Baas P, Kessler PJA, Slik JWF, Ter Steege H, Raes N (2011) Human and environmental influences on plant diversity and composition in Ben En National Park, Vietnam. J Trop For Sci 23(3):328–337, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23616978

Hoang VS, Nanhe X, Vu VD, Luu HT (2013) A new species of Hopea (Dipterocarpaceae) from Vietnam. Glob J Bot Sci 1:29–32. doi:10.12974/2311-858X.2013.01.01.5

Hua Z (2013) The floras of southern and tropical southeastern Yunnan have been shaped by divergent geological histories. PLoS ONE 8(5):e64213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064213

Huang W, Liu J, Wang YP, Zhou G, Han T, Li Y (2013) Increasing phosphorus limitation along three successional forests in southern China. Plant Soil 364:181–191. doi:10.1007/s11104-012-1355-8

Huy LQ (2012) Growth, demography and stand structure of Scaphium macropodum in differently managed forests in Vietnam. Dissertation, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Huynh VK, Tran TA, Nguyen VT (2016) The plants of Bach Ma National Park. National Park Authority, Hue City, Vietnam [in Vietnamese]

IFRI (2004) Field Manual. International Forestry Resources and Institutions, School of Natural Resources. University of Michigan, USA

IUCN (2016) The IUCN Red List of threatened species. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland. http://www.iucnredlist.org/. Accessed 15 Sept 2016

Joliffe L (2014) Tourism and cultural change. Volume 38: Spices and tourism. Destinations, attractions and cuisines. Channel View Publications, Bristol, UK

Kent M (2012) Vegetation description and data analysis. A practical approach. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, West Sussex, UK

Khopai O, Elliot S (2003) The effects of forest restoration activities on the species diversity of naturally establishing trees and ground flora. In: Sim HCS, Appanah S, Durst PB (eds) Bringing back the forests: Policies and practices for degraded lands and forests. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Bangkok, Thailand, pp 295–315

Kitamura S, Yumoto T, Poonswad P, Chuailua P, Plongmai K, Maruhashi T, Noma N (2002) Interactions between fleshy fruits and frugivores in a tropical seasonal forest in Thailand. Oecologia 133:559–572. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-1073-7

Kormann U, Scherber C, Tscharntke T, Klein N, Larbig M, Valente JJ, Hadley AS, Betts MG (2016) Corridors restore animal-mediated pollination in fragmented tropical forest landscapes. Proc R Soc B 283:20152347. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2347

Kuznetsov A, Guigue AM (2000) The forests of Vu Quang Nature Reserve. A description of habitats and plant communities. Vu Quang Nature Reserve Conservation Project, WWF, Hanoi, Vietnam

Laurance WF (1997) Biomass collapse in Amazonian forest fragments. Science 278:1117–1118. doi:10.1126/science.278.5340.1117

Laurance WF, Camargo JLC, Luizão RCC, Laurance SG, Pimm SL, Bruna EM, Stouffer PC, Williamson GB, Benítez-Malvido J, Vasconcelos HL, Van Houtan KS, Zartman CE, Boyle SA, Didham RK, Andrade A, Lovejoy TE (2011) The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: a 32-year investigation. Biol Conserv 144(1):56–67. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.09.021

Lim TK (2012) Artocarpus rigidus. In: Lim TK (ed) Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants. Volume 3: fruits. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp 348–350

Lopes AV, Girão LC, Santos BA, Peres CA, Tabarelli M (2009) Long-term erosion of tree reproductive trait diversity in edge-dominated Atlantic forest fragments. Biol Conserv 142:1154–1165. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.01.007

Lowe AJ, Cavers S, Boshier D, Breed MF, Hollingsworth PM (2015) The resilience of forest fragmentation genetics – no longer a paradox – we were just looking in the wrong place. Heredity 115:97–99. doi:10.1038/hdy.2015.40

Lü X-T, Tang J-W (2010) Structure and composition of the understorey treelets in a non-dipterocarp forest of tropical Asia. For Ecol Manage 260:565–572. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.05.013

MARD (2009) Circular No 34/2009/TT-BNNPTNT of June 10, 2009, on criteria for forest identification and classification. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), Hanoi

Magurran EA (2007) Measuring Biological Diversity. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford

McElwee P (2004) You say illegal, I say legal. The relationship between ‘illegal’ logging and land tenure, poverty, and forest use rights in Vietnam. J Sustainable For 19(1–3):97–135. doi:10.1300/J091v19n01_06

McElwee P (2008) Forest environmental income in Vietnam: household socio-economic factors influencing forest use. Environ Conserv 35(2):147–159. doi:10.1017/S0376892908004736

McElwee P (2009) Reforesting “bare hills” in Vietnam: Social and environmental consequences of the 5 million hectare reforestation program. Ambio 38(6):325–333. doi:10.1579/08-R-520.1

McElwee P (2010) Resource use among rural agricultural households near protected areas in Vietnam: the social costs of conservation and implications for enforcement. Environ Manage 45(1):113–131. doi:10.1007/s00267-009-9394-5

McElwee P (2016) Forests are gold. Trees, people and environmental rule in Vietnam. University of Washington Press, Seattle, USA

Meyfroidt P, Lambin EF (2008) The causes of reforestation in Vietnam. Land Use Policy 25:182–197. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.06.001

MoNRE (2011) Vietnam’s implementation of the biodiversity convention. 4th country report (Report to the Biodiversity Convention Secretariat). Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Vietnam (MoNRE), Ha Noi, https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/vn/vn-nr-04-en.pdf

Nelson DW, Sommers LE (1996) Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. In: Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3: Chemical Methods. SSSA Book Series 5.3: 961–1010. doi:10.2136/sssabookser5.3.c34

Ngo DT, Webb EL (2008) Combining local ecological knowledge and quantitative forest surveys to select indicator species for forest condition monitoring in central Viet Nam. Ecol Indic 8:767–770. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2007.09.002

Ngo DT, Webb EL (2016) Reconciling science and indigenous knowledge in selecting indicator species for forest monitoring. In: Tran TN, Ngo DT, Hulse D, Sharma S, Shivakoti G (eds) Redefining diversity and dynamics of natural resources management in Asia, vol 3, Natural resource dynamics and social ecological systems in Central Vietnam: development, resource changes and conservation issues. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 125–138

Nguyen HH, Uria-Diez J, Wiegand K (2016) Spatial distribution and association patterns in a tropical evergreen broad-leaved forest of north-central Vietnam. J Veg Sci 27:318–327. doi:10.1111/jvs.12361

Noguchi H, Itoh A, Mizuno T, Sri-ngernyuang K, Kanzaki M, Teejuntuk S, Sungpalee W, Hara M, Ohkubo T, Sahunalu P, Dhanmmanonda P, Yamakura T (2007) Habitat divergence in sympatric Fagaceae tree species of a tropical montane forest in northern Thailand. J Trop Ecol 23(5):549–558. doi:10.1017/S0266467407004403

Polesny Z, Verner V, Vlkova M, Banout J, Lojka B, Valicek P, Mazancova J (2014) Non-timer forest products utilization in Phong Dien Nature Reserve, Vietnam: Who collects, who consumes, who sells? Bois For Trop 322(4):39–49

Popradit A, Srisatit T, Kiratiprayoon S, Yoshimura J, Ishida A, Shiyomi M, Murayama T, Chantaranothai P, Outtaranakorn S, Phromma I (2015) Anthropogenic effects on a tropical forest according to the distance from human settlements. Sci Rep 5:14689. doi:10.1038/srep14689

Potts MD, Ashton PS, Kaufmann LS, Plotkin JB (2002) Habitat patterns in tropical rain forests: a comparison of 105 plots in Northwest Borneo. Ecology 83(10):27–2797. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[2782:HPITRF]2.0.CO;2

Raich JW, Khoon GW (1990) Effects of canopy openings on tree seed germination in a Malaysian dipterocarp forest. J Trop Ecol 6:203–217. doi:10.1017/S0266467400004326

Rundel PW (1999) Conservation priorities in Indochina – WWF desk study. Forest habitats and flora in Lao PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam. World Wildlife Fund, Indochina Programme Office, Hanoi, Vietnam

Sharma S, Shivakoti G, Thang TN, Dung NT (2016) Is Vietnam legally set for REDD + ? In: Tran TN, Ngo DT, Hulse D, Sharma S, Shivakoti G (eds) Redefining diversity and dynamics of natural resources management in Asia, vol 3, Natural resource dynamics and social ecological systems in Central Vietnam: development, resource changes and conservation issues. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 205–218

Sidle RC, Ziegler AD, Negishi JN, Nik AR, Siew R, Turkelboom F (2006) Erosion processes in steep terrain – truths, myths, and uncertainties related to forest management in Southeast Asia. For Ecol Manage 224:199–225. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2005.12.019

Sikor T, To PX (2011) Illegal logging in Vietnam: lam tac (forest hijackers) in practice and talk. Soc Natur Resour 24:688–701. doi:10.1080/08941920903573057