Abstract

Background

Information about competition responses is mainly available for monospecific stands or mixed stands with a small number of species. Studies on complex multi-species and highly structured forest ecosystems are scarce. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to quantify competition effects and analyse competition responses in a species-diverse afrotemperate forest in South Africa, based on an observational study with mapped tree positions and long-term diameter increment records.

Methods

The sensitivity to competition was analysed for individual species and involved the calculation of the slope of the linear relation between the value of a competition index (CI) and diameter growth as a measure of sensitivity. In a next step different competition indices were combined and tree diameters were grouped in three classes as surrogates for canopy status and ontogenetic stage.

Results

Five competition indices were found to be effective in showing sensitivity to competition for a number of canopy and sub-canopy species. Significant linear regressions were fitted for 18 of a total of 25 species. Species reactions varied significantly in their sensitivity to the different CIs. The indices were classified as belonging to two groups, those that responded more to local crowding and those that are more sensitive to overtopping, which revealed species-specific sensitivities to both factors. The analysis based on diameter classes revealed that species clearly changed their sensitivity to crowding or overtopping depending on diameter. Canopy and sub-canopy species showed distinct differences in their reactions.

Conclusions

The application of multiple CIs brought novel insights relating to the dynamics of afrotemperate forests. The response patterns to different competition indices that focus on crowding and overtopping are varied and tree diameter dependent, indicating that oversimplified assumptions are not warranted in the interpretation of CI- growth relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1Background

The natural world is to a great extent shaped by the interaction between organisms, in which the fitness of one is lowered by the presence of another (Begon et al. [1996]). This interaction, known as competition, refers to the relationship between members of the same or different species in which individuals are adversely affected by those having similar resource requirements, such as moisture, nutrients or light. Competition is one of many interacting biotic and abiotic factors that affect the structure of a forest community (Sahney et al. [2010]). Facilitation is another, but the focus of this study is on competition. In this context, it is important to differentiate between competition effects and response to competition.

In a forest community, a competition effect is some measure of the aggregate “effect” on the performance of a specific tree by its competing neighbours. Competition effects can occur above and belowground ((Cahill [1999]; Cahill [2002]); (Song et al. [2012])) and involve a reduction in resource availability. A direct assessment of resource availability is usually very labour intensive and includes measurements of many variables such as light, water and nutrient availability under field conditions. For this reason, the aggregate effect is frequently estimated using a competition index (CI) instead, which may include a measure of density, the relative size or available growing space of a reference tree, the number and proximity of immediate neighbours, or estimates of shading and constriction.

Possibly the earliest recorded index is the available growing space index (German: Wachsraumzahl) applied by (Seebach [1846])a, which is expressed by the observed crown diameter of a tree divided by its breast height diameter (dbh). The greater its value, the greater is the tree’s potentially available growing space and the less is the competition effect. Various techniques for estimating available growing space have been proposed ((Green and Sibson [1977]); (Lee [1980]); (Nance et al. [1988])). A common approach involves the use of a Voronoi polygon, which contains the set of all points that are positioned closer to the centre tree in that polygon than to any other tree. (Pukkala [1989]) describes a simulation study based on a mapped stand of Pinus sylvestris with an application of the ecological field theory, which is based on the assumption that each tree reduces the availability of radiation, water and nutrients by its roots, crown and stem. Each of these trees generates a field of resource use that can be described mathematically by a distribution function around each tree. The fields are then added up and in projected to the ground where they form the field map.

The most common forms of physical impediment within a group of trees interacting with each other are constriction of the growing space and shading. However, (Assmann [1953]) pointed out that mechanical constriction by neighbouring trees limits the expansion of a tree crown and constitutes an element of competition. The available amount of light can have a similar limiting effect. So it is no surprise that CIs focussed on shading and overtopping have proven to be fairly reliable predictors when tree growth was simulated in light limited environments. Canham et al. ([1999]) for example developed a gap light index that takes into account the open areas of the sky where the tree crown can receive photon flux for mixed stands in North America. In extension of Canham’s idea, hemispherical projections of neighbouring trees similar to fisheye- photos were simulated to describe competition for trees ((Courbaud [1995]); (Biber [1996])), and branches (Seifert [2003]). A large body of distance dependent competition indices are typically making use of distance to neighbours and the proportion of the focus tree’s dimension in relation to other trees (see (Biging and Dobbertin [1992]) and (Bachmann [1998]) for reviews). Prominent examples are the Hegyi indexb (Hegyi [1974]) basal area of the larger trees as proposed by (Wykoff et al. [1982]), (see also (Coomes and Allen [2007])) or the cone based shading index used by (Pretzsch [1992]). Despite not directly calculating shade they often emphasise the effect of larger trees and thus have a stronger focus on light related competition as experienced by overtopping.

However, also more local density related indices, describing local crowding, have been reported to provide good results for growth prediction, such as the local basal area ((Steneker and Jarvis [1963]); (Mailly et al. [2003]); (Coomes and Allen [2007]); (Seydack et al. [2011])).

An important step was the combination of light and crowding focussed CIs by (Canham et al. [2004]), extended in (Coates et al. [2009]), who applied a rigorous analysis to test the effects for different conifer species in British Columbia. Major outcomes of their study were that tree size is related to the sensitivity of a species to a CI and species display strongly different reactions to competition. Based on a CI study (Coomes and Allen [2007]) also showed tree size dependent effects on competition. Whereas competition for nutrients affected trees of all sizes, competition for light was mainly affecting smaller trees in Nothofagus stands of New Zealand. (Coates et al. [2009]) provided further evidence that competitive regimes might change during the lifetime of a tree.

Competition response is the degree to which the performance of a reference tree is reduced given the competition effect of the neighbours. Some trees are more sensitive to competition than others. The degree of indifference or sensitivity depends on the species, resource limitation and age. (Van Daalen [1993]) was one of the first to provide quantitative proof on the influence of crown position on growth of trees in the mixed evergreen forests of the Knysna area at the southern coastline of South Africa. Light demanding trees, for example, may be less sensitive to shading at a young age, but they become gradually more sensitive with increasing age (cf. (Valladares and Niinemets [2008]) for a review). Facilitation, which results in positive interactions between individuals, may significantly complicate the study of competition response. A typical example is that certain mixtures of tree species increase the nutrient availability, nutrient uptake or nutrient use efficiency ((Rothe and Binkley [2001]); (Richards et al. [2010]); (Forrester [2014])). However, isolating specific responses to different mixtures at varying levels of density is a challenging task.

Shifts in the root/shoot ratios reflect strategic allocation of plant biomass for resource acquisition and indicates specific response to competition (Casper et al. [1998]). Numerous studies support the idea that resource availability influences biomass partitioning (Wilson [1988]). (Bolte et al. [2004]) reported that interspecific competition reduced the root/shoot ratio in the study of above- and below-ground biomass in mixed stands of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) and Norway spruce (Picea abies). Plants adjust their above- and below-ground biomass structure in response to environmental changes. Water and photoactive radiation are key resources that may affect the morphological response of individuals ((Seifert [2003]); (Longuetaud et al. [2008]); (Seifert et al. [2010]); (Leuchner et al. [2012])) as well as the structural composition of a forest community (Sahney et al. [2010]). (Bond-Lamberty et al. [2002]) found that foliage production is highly sensitive to light, water and nutrient conditions. Recent progress in explaining competition effects at the individual and stand level was achieved in simulation studies that could extend competition concepts in order to explain species-specific sensitivity to competition for resources and the interaction with stress (Rötzer et al. [2012]).

The response to aboveground competition includes changes in the biomass structure and allometry of aboveground components ((Seifert [2003]); (Wang et al. [2011]); (Rötzer et al. [2012])). However, this may be insufficient to explain the response to belowground competition. Due to technical problems of sampling and measurement, belowground competition has been given little attention compared with aboveground competition in mature multi-species forests ((Casper and Jackson [1997]); (Bauhus et al. [2000]); (Curt & Prévosto [2003]); (Bolte et al. [2004])). It has been reported that early-successional, fast-growing and light-demanding species are the most responsive to the removal of root competition and are capable of very rapid morphological adaptation ((Messier and Nikinmaa [2000]); (Gunaratne et al. [2011])), but isolating the effects of aboveground vs. belowground competition is difficult.

Additional to considerations of above- and below-ground competition effects the inclusion of the spatial symmetry of competition might be desirable ((Pretzsch [1992]); (Seifert [2003])). A sound argument for integrating such spatial effects is provided by the fact that there is not only a substantial effect on crown and branch development (Seifert [2003]), but also first evidence that spatially irregular growing conditions reduce space-use efficiency (Ackerman et al. [2013]).

Information about competition response patterns is mainly available for monospecific stands or mixed stands with a small number of species. Studies on complex multi-species and highly structured forest ecosystems are scarce ((Moravie et al. [1999]); (Coates et al. [2009]); (Seydack et al. [2011])). Accordingly, the objective of this study is to quantify competition effects and analyse competition response in a highly species-diverse afrotemperate forest in South Africa, based on spatial tree distribution data and long-term diameter increment records, obtained from a permanent observational study. The following specific questions are addressed:

-

1)

Are there species-specific differences in the correlation of diameter increment with distance-dependent competition indices? The ecological question is whether the complex relationships of competitive tree-tree interactions in a sub-tropical afrotemperate stand can be captured by a rather simple index. With this question another one is addressed: is there a generic index that is useful for modelling competitive sensitivity equally well across species?

-

2)

Do tree species respond differently to crowding or overtopping in different ontogenetic stages? This includes the question whether the correlation of diameter increment with different indices allows conclusions on the specific ecological behaviour of a tree species and whether a general sensitivity of trees in different diameter classes has additional information value and takes cognisance of effects where CIs deliver complementary or redundant explanation values.

2Methods

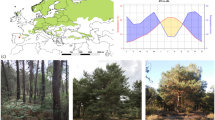

The study area, known as Diepwalle Research Site (517 m a.s.l.) is part of the Southern Cape Forests, which are found on the coastal platform and foothill zone of the Outeniqua and Tsitsikamma mountains in South Africa between 190 and 520 m a.s.l. (Seydack et al. [2012]). The average annual maximum temperature for the region is 19.2°C while the average minimum is 11.1°C. Rainfall occurs in all seasons and the climate can be considered transitional to the tropical/subtropical and temperate regions. The mean annual precipitation may vary between 700 and 1230 mm, subject to orographic influences and is increasing from west to east. The Southern Cape Forests, part of the afromontane group of forests (White [1978]), are classified as Southern Cape Afrotemperate Forests (Geldenhuys and Mucina [2006]). They are broadly tropical-type forests in terms of structure and function (Seydack et al. [2011]; Seydack et al. [2012]). The Diepwalle Research Site is located within the cool, moist upper foothill forest zone of these forests (Seydack et al. [2012]).

2.1 Canopy structure of the Diepwalle forest

Most forests display several reasonably well-defined layers of woody vegetation. The tallest trees, known as “emergents”, may rise well above the main canopy. “Canopy trees” intercept most of the radiation. Directly beneath the canopy there is another layer of woody vegetation, known as the sub-canopy layer (see Figure 1). The sub-canopy layer usually includes immature canopy trees and shade tolerant species that never reach canopy height. The shrub layer is formed by low woody plants, sometimes with multiple shoots or stems from the base, which attain only small heights at maturity. Canopy positions for individual species are indicated in Table 1. Canopy species with relatively high light responsiveness according to the crown position response index are Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus, Podocarpus falcatus, Psydrax obovata subsp. obovata and Olea capensis subsp. macrocarpa. Podocarpus latifolius, Apodytes dimidiata, Curtisia dentata and Ocotea bullata are comparatively shade-tolerant (Seydack et al. [2011]). Derived from maximum negative water and negative osmotic potential values determined by (Mitlöhner [1998]) we place canopy species into four perceived groups of declining tolerance to water deficits. 1) Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus; 2) Podocarpus falcatus, Curtisia dentata, Psydrax obovata subsp. obovata; 3) Nuxia floribunda, Ocotea bullata and 4) Olea capensis subsp. macrocarpa, Apodytes dimidiata, Podocarpus latifolius.

Schematic diagram showing typical layers in the afrotemperate forest of the Diepwalle observational study: Emergent (E) and canopy species (C) dominate the canopy layer, while the sub-canopy layer comprises of immature canopy species (I) and shade tolerant species (S) that never reach canopy height. The shrub layer is not shown in this diagram.

2.2 Data

The data set for this study was obtained from the Diepwalle research area, which was established in 1937 on the Diepwalle State Forest. The study sites were established in their present form during 1972 by officers of the former Saasveld Forestry Research Centre (of the South African Forestry Research Institute) and were remeasured in 1978. Further remeasurements took place in 1987, 1997 and 2007 under the initiative and jurisdiction of the Scientific Services Section in Knysna (of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry and of the South African National Parks since 2006). The research area is subdivided into strips (virees). The data used for the calculation of competition indices originated from Virees 3/4/ 5 and 7 (part), 8 and 9 (part), out of a total of 27 strips (total 44.4 ha). The selection of the virees was made based on the availability of spatial information on tree positions. The area used for the competition calculation was 60 m by 400 m since the total plot was slightly trapezoidal and the calculations of some CIs made an orthogonal shape necessary. Repeated dbh and a set of spatial tree coordinates were available for two distinct areas, separated by a strip without spatial information (Figure 2). The areas amounted to 4.55 ha (370 m × 123 m) with 760 trees · ha−1 for the larger area and 3.86 ha (386 m × 79 m) with 652 trees · ha−1 for the smaller.

2.3 Measuring competition effects

The literature on forest density and competition is extensive and covers a wide range from simple indices to complex models of light interception. Prominent above-ground density measures are basal area ((Assmann [1961]); (Kramer [1988])), relative spacing and stand density index (Reineke [1933]), leaf area index (Vose and Allen [1988]) and crown competition factor (Krajicek et al. [1961]). In forests where the spatial pattern is stationary across space, i.e., where the density of individuals λ(x) does not depend on the location x, the competition effects may be assessed by using a distance-independent measure of competition without requiring spatial information. A plausible distance-independent index should account simultaneously for the population attribute stand-density and the tree attribute of relative social class of the tree within the stand (Gadow [1996]).

Numerous competition indices have been used in analysing forests with mapped trees. They include overlapping zones of influence (Gerrard [1969]), distance-weighted size ratios ((Hegyi [1974]); Lee and Gadow ([1997])), and available growing space ((Brown [1965]); (Hessenmöller [2001])). The potential for developing new ones is boundless. Five distance-dependent measures of competition are being used in this study. They are briefly described in Table 2, using a simplified formula and a schematic diagram. Four of the five competition indices (BAL, lBA, CR13 and ITH) are based on direct observations in the field. The KKL-t index relies on quantities which have to be estimated.

The basal area of larger trees (BAL) is defined as the sum of the basal areas of all trees larger than the reference tree within a circular competition zone. In our study, the reference tree is located at the centre of the circle with a radius equal to twice the mean distance between trees, calculated as the square root of 10000 divided by the number of trees per ha. The radius was 7.3 m for Virees 3/4/5 and 7.8 m for Virees 7/8/9 in the Diepwalle study area. The BAL index combines individual tree basal area percentiles with the density measure stand basal area (see (Wykoff et al. [1982]) for details). It thus mainly estimates the effects of overtopping and radiation exclusion.

The local basal area (lBA) is defined as the basal area of all trees, excluding the reference tree, within a circle of influence (Steneker and Jarvis [1963]). The reference tree is located at the centre of the circle and the circle radius is equal to two times the mean distance between trees as in the case of the BAL index. In a previous study (Coomes and Allen [2007]) and (Seifert et al. [2011]) used local basal area to describe crowding as a surrogate for below ground competition because a) it also includes the trees that are smaller than the reference tree and b) the circle of influence is not too big, so that close neighbours exert the crowding effect.

The crowding index CR13 (Seydack et al. [2011]) represents the sum of all dbh values of trees between 10 to 30 cm in diameter within a given search radius. The use of dbh excludes a quadratic impact of bigger trees as found in the lBA and BAL indices and should thus give smaller trees a proportionally higher impact on the calculated CI value. For consistency the same search radius as for all previous CIs was chosen, which was considerably smaller than the one originally used by (Seydack et al. [2011]), which was 11.3 m.

The iterative Hegyi index (ITH) proposed by (Lee et al. [2004]) takes account of the size ratios and distances between the reference tree and its competitors within a circle of influence equal to that used for the BAL index. The ITH is thus related to the well-known Hegyi index (Hegyi [1974]), but the important difference is that trees that are not directly facing the reference tree are not considered to be active competitors. Further details are presented in Gadow and Hui ([1999]).

The KKL index ((Pretzsch [1992]; Pretzsch [2009]), p. 293) is the only CI applied in this analysis that requires information about tree height and crown dimensions. The search for potential competitors is based on a cone with an angle of 60° that is inserted with its tip at 60% of the tree height. The crown tips of all neighbouring trees that are presumed to reach inside that cone are considered to be competitors. For those the angle from the tree tip to the virtual cone mantle is calculated (angle β in Table 2). This is used as a measure of competition, which is additionally weighted by the cross-sectional crown area of the competitor in relation to the subject tree (CCAj/CCAi). A generalised modification of the KKL, called KKL-t further on, had to be used that ignored many species-specific adaptations because the needed empirical data was not available. The light transmission factor (TM) was set constant to 0.8 since species-specific information was not available and no other of the applied CIs was modified at the species level. Crown diameters were calculated using the model for Fagus sylvatica (Pretzsch [1992]) in the absence of species-specific models for afrotemperate forests. However, height and crown length were calculated using the locally developed parameters from (Seifert et al. [2011]). Tree species without valid height-diameter models were assigned to corresponding species with available models.

A common challenge in the application of distance dependent CIs is the fact that typically no spatial and size information is available on trees outside the area of interest but that these trees de facto contribute to the competition. Ignoring the effect would thus mean a severe underestimation of competition at the edges. There are two possible generic solutions for this problem: one is to apply an edge correction algorithm to plausibly simulate competition from the edge-side dependent on the structure (see (Biber [1996]); (Pommerening and Stoyan [2006]); (Pretzsch [2009]), p. 326–336). The other solution is to cut the size of the actual plot and limit inferences to trees that are unaffected by the edge. This may be effectively done by making use of the search radius of the respective CI. We applied both methods as it appeared appropriate. To prevent an edge bias, trees with distances to the border less than the circle of influence were excluded for BAL, lBA and ITH. As stated before, the two plots (Virees 3/4/5 and Virees 7/8/9) were treated as separate plots for the edge correction and competition calculation. Thus all trees near the edges were excluded. In the case of the KKL- index a simple exclusion is not possible because the potentially large search radius would exclude too many trees from the analysis. For the KKL-t we replicated the structure in the plot outside by shifting all trees by the width/length of the plot, thus replicating the entire plot as tiles, which is a proven method for edge correction in CI calculation procedures (Pretzsch [2009]).

2.4 Data preparation

Data for the analysis of the correlation between CIs and tree increment were prepared in order to obtain the most accurate spatial representation of the stand for the CI calculations and to eliminate implausible increments from the calculation.

The first step was to obtain a valid and plausible dbh for each tree at each time period in order to compute the competition indices as accurately as possible. The second step was to exclude implausible increment measurements from the data for the increment response. Missing diameters of trees for certain dates were derived from a tree individual linear regression of the diameters over time, limiting the slope to positive numbers, i.e., not allowing the tree diameter to shrink. This interpolation was exclusively applied to fill gaps for a few missing dbh values for competitors since excluding the trees would have significantly biased the competition calculation for focus trees. All trees with missing dbh records were excluded from the analysis of competition sensitivities.

Outliers were removed from further analysis if an overall increment of 20 cm in 40 years or an annual increment of 0.7 cm were exceeded in accordance with the empirically determined potential growth limits at the site. These growth limits were determined based on long term data from the site itself and long term inventories on permanent sample plots in a larger area. Additionally, all increment measurements smaller than −0.01 cm per year and trees with diameters less than 10 cm were excluded from the calculation. The CI values were trimmed at the 99.9% percentile. The main characteristics of data set used in the analysis are presented in Table 1.

2.5 Steps of the analysis of the sensitivity to competition

The sensitivity to competition was analysed in two steps:

-

1)

analysis of the sensitivity of the tree species to specific CIs, where one index at a time was used to quantify competition response using a linear regression;

-

2)

analysis of the simultaneous contribution of different CIs in interaction with a multiple regression, where the data was differentiated in diameter classes in a second step to detect also changes in competitive sensitivity due to social position in the crown layer and ontogenetic development.

2.6 Specific sensitivity to competition

Sensitivity to competition was expressed by the slope of the linear relation between dbh increment and the different competition index values.

Strong negative correlations signify a substantial competitive sensitivity, whereas non-significant slope parameters indicate an insubstantial or no sensitivity to competition. The lBA and the CR13 indices are intuitively more suited to measuring local crowding, while the BAL and KKL-t indices emphasise overtopping effects and thus shading since they both exclude smaller trees in the selection of competitors. The ITH includes proximity and relative size of competitors and thus measures both shading as well as crowding but will focus more on overtopping when compared to the CR13 and lBA indices.

None of the indices clearly differentiates between crowding and shading effects and each index contains a measure of both. However, the mathematical formulation of the CIs allows for ranking according to their expected sensitivity to local crowding: CR13 > lBA > ITH > BAL & KKL-t.

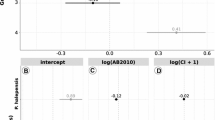

2.7 Interaction of CIs and ontogenetic changes in competitive reaction

It is quite possible that competition effects are partly complementary or partly redundant. Hence an multi-CI approach was used in this step of the analysis where two indices that were intuitively more focussing on overtopping effects (KKL-t and ITH) entered in stepwise multiple linear regression with two indices that had a more pronounced focus on competition by local crowding (lBA and CR13). To trace potential influences of canopy position, the data was classified in three different classes to dbh (10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, >30 cm). The regression was initiated with the full model and used a stepwise exclusion algorithm, based on an optimal AIC value in the statistical modelling language R (R-Core Team [2012]). Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated to ensure that severe collinearity was excluded and all models with insignificant coefficients were discounted as well. All models that were not significant at the model level were excluded from further analysis as well as all models where no CI contributed significantly. All models which had less than 30 tree observations and a VIF > 5 were also discarded.

3Results

3.1 Species-specific sensitivity to competition

As a result of the regression analysis, it became evident that 18 of the total of 25 species in the study area showed a significant sensitivity to at least one competition index (Table 3). Higher CI-values had a negative effect on increment for all species except for V and WH. For the BAL, lBA, CR13, ITH and KKL-t, respectively, 14, 11, 7, 14 and 13 sensitive species were identified.

The BAL and ITH indices were significant in 14 out of the 25 species. No single CI emerged from this analysis which had convincingly strong correlations to diameter increment in the majority of species.

In Figures 3 and 4 species-specific sensitivities to two indices are illustrated as an example for a more below-ground (lBA) and a more light oriented index (KKL-t). It is obvious from the two graphs that there is only a partial overlap in the sensitivities between the species regarding the two indices (see also Table 3). However, some indices seem to provide similar information. For example, tree species that reacted to the ITH-index were often also sensitive to the KKL-t index.

3.2 Interaction of CIs in multiple CI approach and ontogenetic changes in competitive reaction

While the above mentioned species-specific sensitivity was addressing the bulk reaction of all diameter classes under the assumption that every CI provides independent competition information, the multiple regression facilitated a differentiation between diameter classes and accounted for the overlap of explanatory power among different CIs (Table 4). These results show an additional ontogenetic change in the species sensitivity to competition that is reflected in changes of the sensitivity to different CIs.

Looking at Table 4 it is obvious that most of the coefficients were negative but due to interaction effects between the CIs, several positive coefficients were found as well. There is a species-specific change of competition sensitivity that was caused by different contributions of CIs in different diameter classes (Table 5). A proportion of the sub-canopy species was not sensitive to any CI at all. Comparing the change of sensitivity patterns over dbh-classes, marked differences within the canopy-forming species were evident, but also between canopy and sub-canopy species. Three main archetypes of changes in competitive reaction could be identified within the canopy species: i) the light demanding species (Kal, Kers), that showed a high sensitivity to light focused CIs throughout the diameter classes, ii) the species that changed from light sensitivity to edaphic sensitivity or non-responsiveness (SH, V WP, YH), and iii) a species group that clearly changed response from mixed (light and edaphic) in the smaller dbh-class, to light focused in the middle diameter class and switched to a more edaphic response in the higher dbh-class (Ass, Geel, Sw). Kw could not be attributed to any of these groups, since it changed from an edaphic sensitivity in the lowest dbh-class to a mixed sensitivity in the highest.

The sub-canopy species, which were not represented in the upper diameter classes, displayed a response to edaphically focused CIs (RH) or mixed responses (Kam, Saf, Ke) or were entirely non-responsive to any CI (KH, N, Btol).

In total sub-canopy species behaved as expected and showed either no sensitivity or a more pronounced sensitivity to local crowding, expressed by the correlations with the CR13 and lBA indices. An exception was Cassine eucleiformis that showed an increasing light sensitivity with larger diameters, marking it as a species that will have to wait opportunistically for disturbances of sufficient size to grow. The canopy species showed a distinct differentiation, following three main archetypical reactions. The first group comprising Curtisia dentata, Maytenus peduncularis and Podocarpus latifolius displayed a mixed reaction in the lower dbh-classes with a sensitivity to CIs with a light and edaphic focus, followed by a distinct light sensitive phase in the middle dbh class where trees are growing towards the canopy layer and, finally, in the phase when the trees had established in the canopy, an edaphic sensitivity.

A second group including Podocarpus falcatus and Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus showed an exclusive response to light focussed CIs, whereas species such as Apodytes dimidiata, Nuxia floribunda, Ocotea bullata, and Olea capensis macrocarpa changed from light-CI sensitivity to edaphic sensitivity or non-responsiveness with increasing DBH.

4Discussion

The main objective of this study was to analyse competition response patterns in a species-diverse afrotemperate forest in southern Africa, based on mapped tree positions and long-term diameter increment records within the context of a large observational study. One outcome was that the detailed analysis and comparison of competition indices within this study yielded a better understanding of the significance of CI indices for forest ecological research. The results revealed differentiated competition responses of the various tree species in terms of sensitivity to individual CIs, a different general sensitivity to a set of CIs and an ontogenetic change of sensitivity patterns. This confirmed previous results of (Canham et al. [2004]), (Coomes and Allen [2007]) and (Coates et al. [2009]) obtained for species native to North America and New Zealand. Our study also confirmed the viability of the approach to classify CIs according to their focus on local crowding or overtopping and hence allows inference on light or edaphic competition. The obtained results based on the sensitivity to edaphic and light competition correspond well with expert knowledge on the species and create the expectation that a simultaneous CI approach, as proposed in this study, could be used to analyse similar competition effects in other forest communities and thus extend competition analysis studies based on a comparison of CIs (e.g. (Mailly et al. [2003]); (Stadt et al. [2007])).

4.1 Sensitivity to competition

A fair amount of tree species (18 of 25) showed a significant influence of a CI to diameter increment. A share of non-significant regressions was obtained for immature trees of canopy species that typically grow in the understory and seem to be insensitive to the calculated CIs. This insensitivity suggests that the applied CIs did not sufficiently capture the resource availability of these species. For the remaining tree species with significant correlations, the reaction was rather variable, indicating a strong differentiation of the sensitivity to individual CIs between species. However, despite the fact that almost all relationships between diameter increment and single CIs were negative, no CI could be identified as a general best option to characterise the competition across all species in this evergreen mixed forest. In fact single species showed distinct sensitivities to particular CIs.

An aligned differentiation in crowding and overtopping focused CIs revealed clear sensitivities in some species for either one or another CI type but in the majority of species CIs regarding both aspects were represented in fair proportions. This might be a consequence of the fact that a true separation of edaphic and light competition in any of the CI is not possible. Each index contains edaphic as well as light competition effects. However, the more detailed analysis revealed another possible explanation for the mixed response. Increasing the detail of differentiation in the analysis a step further by performing a multiple regressions involving three dbh-classes enabled conclusions on 1) ontogenetic changes of competitive sensitivity and 2) effects of redundancy or complementarity of the explanatory value of CIs.

The results of the multiple CI analysis over different dbh classes correspond well with the perceived light responsiveness of these species. The four most light responsive/demanding canopy species according to the crown position response index, Podocarpus falcatus, Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus, Olea capensis macrocarpa and Psydrax obovata subsp. obovata (Seydack et al. [2011]) show competitive responses for light even in canopy positions (Table 5). An edaphic competitive response at the canopy level was absent in Podocarpus falcatus and Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus, the two species with greater water stress tolerance than the other canopy species (Mitlöhner ([1998])). The pattern of changing competitive responsiveness indicating a need for light at the juvenile stage and moisture stress sensitivity in canopy positions as adults was observed in six canopy species (Table 5). These six canopy species (Curtisia dentata, Podocarpus latifolius, Maytenus peduncularis, Nuxia floribunda, Apodytes dimidiata, Olea capensis macrocarpa) with their characteristic pattern of changing competitive sensitivity pattern from light to edaphic with increasing stem diameter make up more than 90% of canopy-level (trees >30 cm dbh) tree numbers. In canopy species, the effectiveness of the KKL-t index in capturing the light sensitivities of species is confirmed by congruence of their relative light sensitivities as indicated by the crown position response index (Seydack et al. [2011]). Podocarpus falcatus, Olea capensis subsp. macrocarpa, Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus, and Psydrax obovata subsp. obovata have relatively high crown response indices, whereas Podocarpus latifolius, Apodytes dimidiata and Ocotea bullata have low index values (Seydack et al. [2011]). These ratings concur with those of the KKL-t (Figure 4).

These results concur with growth analyses at the stand level by (Seydack et al. [2011]) where sub-canopy cohorts of canopy species were identified as light resource sensitive and those at the canopy level as sensitive to water resource deficiencies. This is furthermore consistent with eco-physiological results obtained by (Mitlöhner [1998]) who found the two light demanding species, Podocarpus falcatus and Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus, which did not show this pattern, being more water stress tolerant than the other six canopy species, which are apparently more prone to water stress when occupying canopy-level positions.

However, the common assumption that a small diameter is always correlated with a physiologically young tree does obviously not always hold true in multi-storey stands because old trees can persist over decades in the shade of the understory before their light conditions are improved. Such trees, although old, may show a physiologically very young behaviour in their growth patterns ((Pretzsch [1992]); (Wright et al. [2000])). Referring to this physiological age one could thus indeed define smaller diameter canopy trees as young trees.

Further tests of multiple regressions with the inclusion of dbh as an independent variable showed complex interaction effects with competition indices, where the dbh was mostly taking over effects of the light focussed CIs. This is not unexpected since tree dbh is positively correlated with relative crown positions in the canopy. However, only trees with diameters exceeding 10 cm were used in the analysis. Thus an extrapolation of the results to smaller diameter trees is only possible with a high degree of uncertainty.

According to the competitive exclusion principle (Gause [1934]), species less suited to compete for resources should either adapt or die out (Law and Watkinson [1989]). The variability of the response to competition between species and ontogenetic stages within species are arguments for the existence of other effects that facilitate coexistence. The findings of this study suggest the existence of mechanisms of temporal and spatial niche differentiation as a form of ecological combining ability as postulated in the theoretical works of (Aarssen [1983]; Aarssen [1989]). His second postulate for coexistence is that several species are equally competitive (competitive combining ability), which was not tested explicitly in this study but is probably the case since several canopy species showed very similar ontogenetic response patterns and would thus compete. The fact that they are co-occur might serve as an indication for an equal competitive ability of these species.

4.2 Outlook

The analysis of various spatial competition effects in an afrotemperate multi-species forest provides some preliminary insights and an impetus for further research that should include nutrient and water effects. This requires an extension of assessment activities in the Diepwalle observational study area. However, how the competition effects vary with environmental conditions has not yet been generally understood. Some insight was provided by (Boyden et al. [2005]) and (Forrester et al. [2011]). (Forrester [2014]) reviewed available articles and combined theoretic approaches with empirical examples on how environmental conditions modify competition. Hulme’s theoretical base for coexistence that involves aspects of resource influence and aspects of niche differentiation ((Hulme [1996]); (Schulze et al. [2005])) might prove a promising avenue for future analysis. Combining specific site effects (Seydack et al. [2011]; Seydack et al. [2012]) and spatially explicit responses to competition, as in the present study, may provide improved understanding of how individual trees compete for resources, including nutrients, water and light. This research depends on long term observational studies with mapped tree data.

Another research objective could involve the differentiation of competition effects in conspecific and interspecific competition components, which might shed further light on species mixing effects (e.g. (Pretzsch et al. [2012]), (Forrester [2014])). Deciphering and separating facilitation and competition effects would add another level of complexity in to the analysis of these multi-species forests. However, such detailed research requires a more comprehensive data base.

5Conclusions

With the presented simultaneous-CI approach a significant proportion of the competition in complex South African multi-species forest can be captured in order to obtain an improved understanding of interactions between trees. Since most of the existing studies in this direction focus on light limited environments this extends the body of knowledge to more edaphically limited stands in Africa.

The differentiation in different dbh-classes as a surrogate for ontogenetic stages of a tree and at the same time also different social situations within a vertically structured canopy revealed different species-specific stages of sensitivity to competition by crowding and/or overtopping, which changed during the lifetime of a tree. Here in particular differences between canopy and sub-canopy species were revealed.

The classification of CIs in crowding and light focussed indices confirmed existing results from other forest types and yielded ecologically relevant results regarding competitive tree-tree interactions in afrotemperate forests.

References

Aarssen LW: Ecological combining ability and competitive combining ability in plants: towards a general evolutionary theory of coexistence in systems of competition. Am Nat 1983, 122: 707–731. 10.1086/284167

Aarssen LW: Competitive ability and species coexistence: a “plants eye” view. Oikos 1989, 56: 386–401. 10.2307/3565625

Ackerman S, Ackerman PA, Seifert T: Effects of irregular stand structure on tree growth, crown extension and branchiness of plantation grown Pinus patula . Southern For 2013, 75(4):247–256.

Assmann E: Zur Bonitierung süddeutscher Fichtenbestände. AFZ 1953, 10: 61–64.

Assmann E: Waldertragskunde. Organische Produktion, Struktur, Zuwachs und Ertrag von Waldbeständen. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, München, Bonn, Wien; 1961.

Bachmann M: Indizes zur Erfassung der Konkurrenz von Einzelbäumen - Methodische Untersuchung in Bergmischwäldern. LMU/LWF, München; 1998.

Bauhus J, Khanna PK, Menden N: Aboveground and belowground interactions in mixed plantations of Eucalyptus globulus and Acacia mearnsii . Can J For Res 2000, 30(12):1886–1894. 10.1139/x00-141

Begon M, Harper JL, Townsend CR: Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities. Blackwell Science, Oxford; 1996.

Biber P: Konstruktion eines einzelbaumorientierten Wachstumssimulators für Fichten-Buchen-Mischbestände im Solling. Ludwig-Maximilians University, Dissertation; 1996.

Biging GS, Dobbertin M: A comparison of distance-dependent competition measures for height and basal area growth of individual conifer trees. For Sci 1992, 38(3):695–720.

Bolte A, Rahmann T, Kuhr M, Pogoda P, Murach D, Gadow K: Relationships between tree dimensions and coarse root biomass in mixed stands of European beech ( Fagus sylvatica L.) and Norway Spruce ( Picea abies [L.] Karst.). Plant Soil 2004, 264(1–2):1–11. 10.1023/B:PLSO.0000047777.23344.a3

Bond-Lamberty B, Wang C, Gower ST: Aboveground and below-ground biomass and sapwood area allometric equations for six boreal tree species of northern Manitoba. Can J For Res 2002, 32: 1441–1450. 10.1139/x02-063

Boyden S, Binkley D, Senock R: Competition and facilitation between Eucalyptus and nitrogen-fixing Falcataria in relation to soil fertility. Ecology 2005, 86: 992–1001. 10.1890/04-0430

Brown GS: Point density in stems per acre. Forestry Research Notes No. 38, New Zealand; 1965.

Cahill JF: Fertilization effects on interactions between above- and belowground competition in an old field. Ecology 1999, 80: 466–480. 10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[0466:FEOIBA]2.0.CO;2

Cahill JF: Interactions between root and shoot competition vary among species. Oikos 2002, 99: 101–112. 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2002.990111.x

Canham CD, Coates KD, Bartemucci P, Quaglia S: Measurement and mdoelling of spatially explicit variation in light transmission through interior cedar-hemlock forests of Bristish Columbia. Can J For Res 1999, 29: 1775–1783. 10.1139/x99-151

Canham CD, lePage PT, Coates KD: A neighborhood analysis of canopy tree competition: effects of shading versus crowding. Can J For Res 2004, 34: 778–787. 10.1139/x03-232

Casper BB, Jackson RB: Plant competition underground. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 1997, 28: 545–570. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.545

Casper BB, Cahill JF, Hyatt LA: Above-ground competition does not alter biomass allocated to roots in Abutilon theophrasti . New Phytol 1998, 140: 231–238. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00271.x

Coates KD, Canham CD, LePage PT: Above- versus below-ground competitive effects and responses of a guild of temperate tree species. J Ecol 2009, 97: 118–130. 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01458.x

Coomes DA, Allen RB: Effects of size, competition and altitude on tree growth. J Ecol 2007, 95: 1084–1097. 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01280.x

Courbaud B: Modélisation de la croissance en forêt irrégulière, − perspectives pour lespessières irrégulières de montagne. Rev For Fr 1995, XLVII: 173. 10.4267/2042/26710

Curt T, Prévosto B: Root biomass and rooting profile of naturally regenerated beech in mid-elevation Scots pine woodlands. Plant Ecol 2003, 167(2):269–282. 10.1023/A:1023904912712

Forrester DI: The spatial and temporal dynamics of species interactions in mixed-species forests: From pattern to process. For Ecol Manag 2014, 312: 282–292. 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.10.003

Forrester DI, Vanclay JK, Forrester RI: The balance between facilitation and competition in mixtures of Eucalyptus and Acacia changes asstands develop. Oecologia 2011, 166: 265–272. 10.1007/s00442-011-1937-9

Gadow K: Modelling growth in managed forests - realism and limits of lumping. Sci Total Environ 1996, 183: 167–177. 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04979-7

Gadow K, Hui GY: Modelling forest development. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht; 1999.

Gause GF: The struggle for existence. The Williams & Wilkins company, Baltimore; 1934.

Geldenhuys CJ, Mucina L: Afrotemperate, subtropical and azonal forests. In The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Edited by: Mucina L, Rutherford MC. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria; 2006:585–614.

Gerrard DJ: Competition quotient – a new measure of the competition affecting individual forest trees. State Univ Agr Exp Stn Res Bull No 20, Mich; 1969.

Green PJ, Sibson R: Computing dirichlet tesselations in the plane. Comp J 1977, 21(2):168–173. 10.1093/comjnl/21.2.168

Gunaratne AMTA, Gunatilleke CVS, Gunatilleke IAUN, Madawala Weerasinghe HMSP, Burslem DFRP: Release from root competition promotes tree seedling survival and growth following transplantation into human-induced grasslands in Sri Lanka. For Ecol Manag 2011, 262: 229–236. 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.03.027

Hegyi F: A simulation model for managing jackpine stands. In Growth models for tree and stand simulation. Edited by: Fries J. Royal College of Forestry, Stockholm; 1974:74–90.

Hessenmöller D: Modelle zur Wachstums- und Durchforstungssimulation im Göttinger Kalkbuchenwald. Universität Göttingen, Dissertation; 2001.

Hulme PE: Herbivory, plant regeneration and coexistence. Ecology 1996, 84: 609–613. 10.2307/2261482

Kraft G: Beiträge zur Lehre von den Durchforstungen, Schlagstellungen und Lichtungshieben. Klindworth’s Verlag, Hannover; 1884.

Krajicek JE, Brinkman KA, Gingrich SF: Crown competition. A measure of density. For Sci 1961, 7: 35–42.

Kramer H: Waldwachstumslehre. Verlag Paul Parey, Hamburg und Berlin; 1988.

Law R, Watkinson AR: Competition. In Ecological concepts. Edited by: Cherrret JM. Blackwell, Oxford; 1989:243–284.

Lee DT: Two-dimensional Voronoi diagram in the LP-metric. J ACM 1980, 27(4):604–618. 10.1145/322217.322219

Lee WK, Gadow K: Iterative Bestimmung der Konkurrenzbäume in Pinus densiflora Beständen. AFJZ 1997, 168(3/4):41–44.

Lee WK, Kv G, Chung DJ, Lee JL: Individual tree dbh-growth in Pinus densiflora and Quercus variabilis mixed stands in central Korea. Ecol Model 2004, 176: 187–200. 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2003.11.012

Leuchner M, Hertel C, Rötzer T, Seifert T, Weigt R, Werner H, Menzel A: Solar radiation as a driver for growth and competition in forest stands. In Growth and defence in plants: resource allocation at multiple scales Edited by: Matyssek R, Schnyder H, Ernst D, Munch JC, Oßwald W, Pretzsch H. 2012, 175–191. 10.1007/978-3-642-30645-7_8

Longuetaud F, Seifert T, Leban JM, Pretzsch H: Long-term dynamics of crowns in sessile oak stands by means of spatial analysis. For Ecol Manage 2008, 255: 2007–2019. 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.01.003

Lorimer CG: Test of age-independent competition indices for individual trees in natural hardwood stands. For Ecol Manage 1983, 6: 343–360. 10.1016/0378-1127(83)90042-7

Mailly D, Turbis S, Pothier D: Predicting basal area increment in a spatially explicit, individual tree model: a test of competition measures with black spruce. Can J For Res 2003, 33(3):435–443. 10.1139/x02-122

Martin GL, Ek AR: A comparison of competition measures and growth models for predicting plantation red pine diameter and height growth. For Sci 1984, 30(3):731–743.

Messier C, Nikinmaa E: Effects of light availability and sapling size on the growth, biomass allocation, and crown morphology of understory sugar maple, yellow birch, and beech. Ecoscience 2000, 7: 345–356.

Mitlöhner R: Pflanzeninterne Potentiale als Indikatoren für den tropischen Standort. Universität Göttingen, Dissertation; 1998.

Moravie MA, Durand M, Houllier F: Ecological meaning and predictive ability of social status, vigour and competition in a tropical rain forest (India). For Ecol Manage 1999, 177: 221–240. 10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00480-0

Nance W, Grissom JE, Smith WR: A new competition index based on weighted and constrained area potentially available. In Forest growth modelling and prediction Edited by: Ek AR, Shifley SR, Burke TE. 1988, 134–142.

Pommerening A, Stoyan D: Edge-correction needs in estimating indices of spatial forest structure. Can J For Res 2006, 36: 1723–1739. 10.1139/x06-060

Pretzsch H: Konzeption und Konstruktion von Wuchsmodellen für Rein- und Mischbestände. Schriftenreihe d. Forstw. Fak. Univ, München; 1992.

Pretzsch H: Forests dynamics, growth and yield. Springer, Berlin; 2009.

Pretzsch H, Dieler J, Seifert T, Rötzer T: Climate effects on productivity and resource use efficiency of Norway spruce ( Picea abies [L.] Karst.) and European beech ( Fagus sylvatica [L.]) in stands with different spatial mixing patterns. Trees 2012, 26: 1343–1360. 10.1007/s00468-012-0710-y

Pukkala T: Prediction of tree diameter and height in a Scots pine stand as a function of the spatial pattern of trees. Silva Fenn 1989, 23: 83–99. 10.14214/sf.a15532

R: A language and environment for statisticalcomputing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, version 2.15.1, Vienna, Austria; 2012.

Reineke LH: Perfecting a stand-density index for even-aged forest. J Agric Res 1933, 46: 627–638.

Richards AE, Forrester DI, Bauhus J, Scherer-Lorenzen M: The influence of mixed tree plantations on the nutrition of individual species: a review. Tree Physiol 2010, 30(9):1192–1208. 10.1093/treephys/tpq035

Rothe A, Binkley D: Nutritional interactions in mixed species forests: a synthesis. Can J For Res 2001, 31: 1855–1870. 10.1139/x01-120

Rötzer T, Seifert T, Gayler S, Priesack E, Pretzsch H: Effects of stress and defence allocation on tree growth: Simulation results at the tree and stand level. In Growth and defence in plants: resource allocation at multiple scales Edited by: Matyssek R, Schnyder H, Ernst D, Munch JC, Oßwald W, Pretzsch H. 2012, 401–432. 10.1007/978-3-642-30645-7_18

Sahney S, Benton MJ, Ferry PA: Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land. Biol Lett 2010, 6(4):544–547. 10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024

Schulze ED, Beck E, Müller-Hohenstein K: Plant Ecology. Springer, Berlin; 2005.

Seebach C: Ertragsuntersuchungen im Buchenhochwalde. Krit Blätter f Forst- u Jagdwiss 1846, 23: 74–88.

Seifert T: Integration von Holzqualität und Holzsortierung in behandlungssensitive Waldwachstumsmodelle. Technische Universität München, Dissertation; 2003.

Seifert T, Breibeck J, Seifert S, Biber P: Resin pocket occurrence in Norway spruce depending on tree and climate variables. For Ecol Manage 2010, 260: 302–312. 10.1016/j.foreco.2010.03.024

Seifert T, du Toit B, Jooste GH, Seibold S, Durrheim G, Seydack A: 2011 Towards an individual tree forest growth model for natural forests in South Africa: testing competition indices to model individual tree diameter growth in afro-temperate forests. Proceedings of the Fifth National National Forest and Woodlands Symposium, Richards Bay South Africa, Richards 2011.

Seydack AHW, Durrheim G, Louw JH: Spatiotemporally interactive growth dynamics in selected South African forests: Edaphoclimatic environment, crowding and climate effects. Forest Ecol Manage 2011, 261: 1152–1169. 10.1016/j.foreco.2010.12.017

Seydack AHW, Durrheim G, Louw JH: Forest structure in selected South African forests: edaphoclimatic environment, phase and disturbance. Euro J For Res 2012, 131: 261–281. 10.1007/s10342-011-0498-0

Song M, Hu Q, Tian Y, Ouyang H: Seasonal patterns of root and shoot interactions in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. J Plant Ecol 2012, 5: 182–190. 10.1093/jpe/rtq032

Spiecker M: Wachstum und Erziehung wertvoller Waldkirschen. Mitt. d. Forstl. Vers. u, Forschungsanstalt Baden-Württemberg; 1994.

Stadt KJ, Huston C, Coates KD, Feng Z, Dale MRT, Lieffers WJ: Evaluation of competition and light estimation indices for predicting diameter growth in mature boreal mixed forests. Ann For Sci 2007, 64(5):477–490. 10.1051/forest:2007025

Steneker GA, Jarvis JM: A preliminary study to assess competition in a white spruce – trembling aspen stand. For Chron 1963, 39: 334–336. 10.5558/tfc39334-3

Sterba H: Forstliche Ertragslehre. Lecture notes (Heft 4), Vienna; 1991.

Valladares F, Niinemets Ü: Shade tolerance, a key plant feature of complex nature and consequences. Annu Rev Ecol, Evol Syst 2008, 39: 237–257. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173506

Van Daalen JC: The value of crown position and form as growth indicators in mixed evergreen forests. S Afr For J 1993, 165: 29–35.

Vose JM, Allen HL: Leaf area, stemwood growth and nutrition relationships in loblolly pine. For Sci 1988, 34(3):547–563.

Wang J, Zhang C, Xia F, Zhao X, Wu L, Kv G: Biomass structure and allometry of Abies nephrolepis (Maxim) in Northeast China. Silva Fenn 2011, 45(2):211–226. 10.14214/sf.113

White F: The afromontane region. In Biogeography and Ecology of Southern Africa. Edited by: Werger MJA. Dr W Junk, The Hague; 1978:464–513.

Wilson JB: Shoot competition and root competition. J Appl Ecol 1988, 25: 279–296. 10.2307/2403626

Wright EF, Canham CD, Coates KD: Effects of suppression and release on sapling growth for 11 tree species of northern, interior British Columbia. Can J For Res 2000, 30: 1571–1580. 10.1139/x00-089

Wykoff WR, Crookston NL, Stage AR: User’s guide to the stand prognosis model. USDA For Serv Gen Tech Rep 1982, No. INT–133: 112.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration with and support (data, scientific input) by South African National Parks. Funding for this study was contributed by three projects, financed by the South African Department of Science and Technology through the National Research Foundation: i) the ‘Green Landscapes’ Project within the Global Change, Sustainability and Society Research Programme of the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa, ii) the EU Marie Curie Project “Climate Fit Forests” and iii) the Project ‘Impact of drought on mortality, ingrowth and diameter increment in the afro-temperate forests of the Southern Cape, South Africa’ funded by the NRF/DST Centre of Excellence of Tree Health and Biotechnology (CTHB) in Pretoria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

T. Seifert conceptualized the article including large parts of the statistical analysis, wrote substantial parts of the manuscript and did most of the figures, S. Seifert was instrumental in conceptualising the analysis, programmed the R-code for the analysis, did most of the data handling and contributed to the text and figures. A. Seydack and G. Durrheim wrote parts of the text, provided data including the data plausibility checks and contributed with important sections to the manuscript, K. v. Gadow, was instrumental in conceptualising the analysis and contributed statistical techniques, as well as substantial parts of the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Seifert, T., Seifert, S., Seydack, A. et al. Competition effects in an afrotemperate forest. For. Ecosyst. 1, 13 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-014-0013-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-014-0013-4