Abstract

Background

Emerging evidence showed that microRNAs (miRs) play critical roles in human cancers by functioning as either tumor suppressor or oncogene. MIR-382 was found to function as tumor suppressor in certain cancers. However, the role of MIR-382 in colorectal cancer (CRC) is largely unknown. Specificity protein 1 (SP1) is highly expressed in several cancers including CRC and is correlated with poor prognosis, but it is unclear whether or not MIR-382 can regulate the expression of SP1.

Methods

MIR-382 expression level was measured by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The connection between MIR-382 and SP1 was validated by luciferase activity reporter assay and western blot assay. Cell counting kit-8 assay and wound-healing assay were conducted to investigate the biological functions of MIR-382 in CRC.

Results

In this study, we found MIR-382 expression was downregulated in CRC tissues and cell lines, and the transfection of MIR-382 mimic decreased cell growth and migration. Furthermore, we identified SP1 was a direct target of MIR-382. Overexpression of MIR-382 decreased the expression of SP1, whereas MIR-382 knockdown promoted SP1 expression. We also observed an inversely correlation between MIR-382 and SP1 in CRC tissues. Additionally, we showed that knockdown of SP1 inhibited cell growth and migration and attenuated the effect of MIR-382 inhibitor on cell behaviors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study describes a potential mechanism underlying a MIR-382/SP1 link contributing to CRC development. Thus, MIR-382 may be able to be developed as a novel treatment target for CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the third most commonly diagnosed cancer type worldwide [1, 2]. Owing to the improvements in therapeutic measures, the incidence rate of CRC has been declined in a worldwide range [3]. However, the CRC incidence and cancer-related death are rapidly increasing in Asian countries [4].

Specificity protein 1 (SP1), a transcription factor, has been demonstrated to play a critical role in the regulation of tumor-associated genes required for tumor survival, progression and metastasis [5]. In most cases, SP1 regulates gene expression mainly through GC-rich region binding but it is also capable to bind GT-rich sequences [6]. Elevated expression of SP1 was identified in several human cancers. For example, SP1 was overexpression in breast cancer and could regulate TINCR-MIR-7-KLF4 axis, which in turn stimulate cell proliferation but suppress cell apoptosis [7]. In ovarian cancer, upregulation of SP1 enhanced VEGF expression and resulted in angiogenesis and migration stimulation in vitro and in vivo [8]. Another study investigated the role of SP1 in hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrated that SP1 regulate cystathionine γ-lyase gene expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines to promote cell proliferation and cell cycle progression [9]. Moreover, SP1 is also found highly expressed in CRC and correlated with tumor metastasis and poor prognosis [10]. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated SP1 is a mediator for various cell behaviors including cell cycle, proliferation, and apoptosis [5, 11, 12]. SP1 has been found to be regulated by multiple miRNAs in several human cancers. In osteosarcoma, MIR-493 was reported to inhibit osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion through targeting SP1 and therefore MIR-493/SP1 axis may be developed as potential therapeutic targets [13]. In glioblastoma multiforme, SP1 upregulation abolished the effects of MIR-376a overexpression on cell proliferation and invasion [14]. In cervical cancer, MIR-296 functions as tumor suppressor via targeting SP1 [15]. However, how SP1 expression was regulated in CRC still need further investigations.

In this study, the expression and biological functions of MIR-382 in CRC was investigated. The results showed MIR-382 was significantly downregulated in CRC, and was associated with poorer 5-year overall survival. Luciferase activity reporter assay and western blot assay revealed that SP1 was a direct target of MIR-382. In addition, functional assays revealed that MIR-382 inhibited cell proliferation and migration through targeting SP1.

Methods

Tissue collection

Colorectal cancer tissues and noncancerous tissues were obtained from 113 patients who underwent treatment between May 2010 and December 2012 at Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute. Patients were excluded from the study if they have ever received anti-cancer treatments. These tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for further usage. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all participates.

Cell culture

Human CRC cell lines HT29, SW480, SW620 and normal colon epithelial cell line FHC were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). CRC cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). FHC cells were incubated in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco). These cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cell transfection

MIR-382 mimics, MIR-382 inhibitor and the corresponding negative control (NC) were obtained from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). SP1 siRNA (si-SP1) and NC was also obtained from GenePharma (Shanghai). To conduct cell transfection, cells were firstly cultured to about 70–90% confluence. Then, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used to transfect the synthetic oligonucleotides (50 nM for miRNAs and siRNAs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from tissues and cell lines using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and was reverse transcribed to cDNA using PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was conducted using SYBR Premix EX Taq™ (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) at ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). U6 snRNA and GAPDH was used as endogenous controls for MIR-382 and SP1 respectively. Expression levels were measured with the relative quantification (2−ΔΔCt) method. The primers for MIR-382, forward 5′-CTGCAATCATTCACGGACAAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGTCGTCGAGTCGGCAATTC-3′; U6 snRNA, forward 5′-ATTGGAACGATACAGAGAAGATT-3′ and reverse 5′-GGAACGCTTCACGAATTTG-3′; SP1, forward 5′-TGGTGGGCAGTATGTTGT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTATTGGCATTGGTGAA-3′; and GAPDH, forward 5′-ATGTCGTGGAGTCTACTGGC-3′ and reverse 5′-TGACCTTGCCCACAGCCTTG-3′.

Western blot

Total protein was obtained from tissue and cells using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Beyotime, Haimen, Jiangsu, China). Protein concentration was measured using Bradford protein kit (Beyotime). Same amounts of protein samples were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane. After blocked with 5% milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with the following antibodies: anti-SP1 rabbit antibody (#9389, Cell signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); anti-E-Cadherin rabbit antibody (#3195, Cell signaling Technology); anti-N-Cadherin rabbit antibody (#13116, Cell signaling Technology); anti-Vimentin rabbit antibody (#5741, Cell signaling Technology); anti-Snail rabbit antibody (#3879, Cell signaling Technology); anti-GAPDH rabbit antibody (#5174, Cell signaling Technology). Signals were detected by with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (#7074, Cell Signaling Technology) and enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime). Band density was analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined by CCK-8 kit (Beyotime). Cells were seeded at a density of 3000 cells/well onto a 96-well plate and cultured for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h at 37 °C. At these above-mentioned points, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for another 2 h. Optical density was then measured at 450 nm.

Cell migration assay

Wound healing assay was conducted to measure cell migration ability. 200 μl pipette tip was used to create wound at cell surface. Photographs were taken at 0 and 48 h after wound was created and wound closure rate was measured based on these photographs using the ImageJ software (NIH).

Luciferase activity reporter assay

Bioinformatics analysis TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/) was used to predict target genes of MIR-382. The wild-type 3′-UTR of SP1 and a mutant sequence of SP1 3′-UTR was sub-cloned into pMIR-REPORT vector (Promega). To measure luciferase activity, cells were transfected with pMIR-SP1-3′-UTR Wt or pMIR-SP1-3′-UTR Mut, together with MIR-382 mimic or NC using Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 h of transfection, cells were harvested to measure luciferase activities using dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences were analyzed with two-tailed Student’s t-test (two groups) or one-way analysis of variance and Tukey test (three or above groups) using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test was used to investigate effect of MIR-382 expression on overall survival. Associations between MIR-382 expression and clinicopathological features were analyzed by Chi square test. Correlation between MIR-382 and SP1 expression was analyzed using Person’s correlation analysis. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant difference.

Results

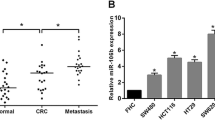

MIR-382 was downregulated in CRC tissues and cell lines

We found MIR-382 expression in 113 pairs of CRC tissues was dramatically downregulated compared with corresponding noncancerous tissues using qRT-PCR (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we measured MIR-382 expression in FHC cell line and three CRC cell lines HT29, SW480, and SW620. These results showed MIR-382 expression was downregulated in CRC cell lines investigated compared with FHC cell line (Fig. 1b). Besides that, we found HT29 cell line has the lowest MIR-382 expression among the CRC cell lines investigated (Fig. 1b).

The aberrant expression of MIR-382 in CRC tissues and cells. a The expression of MIR-382 in 113 pairs of human CRC tissues and surrounding noncancerous tissues. b The expression of MIR-382 in CRC cell lines HT29, SW480, SW620 and human normal colon epithelial cell line FHC. (***P < 0.001) MIR-382: microRNA-382; CRC: colorectal cancer

Clinical significance of MIR-382 expression in CRC

Furthermore, the median of MIR-382 levels was used to classify these patients into two groups: low MIR-382 expression group (n = 59) and high MIR-382 expression group (n = 54). Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test was performed to explore the associations between MIR-382 expression and overall survival of CRC patients, we found low MIR-382 expression predicts poorer 5-year overall survival of CRC patients (Fig. 2). We also found low MIR-382 expression was strongly correlated with Lymph node metastasis and TNM stage through analyzing the associations between MIR-382 and clinicopathological features (Table 1).

MIR-382 overexpression inhibits CRC cell proliferation and migration

In order to investigate the effects of MIR-382 on CRC cell behaviors, we transfected synthetic miRNAs into HT29 cell line. qRT-PCR results showed that MIR-382 was overexpressed in MIR-382 mimic transfected cells compared with NC transfected cells (Fig. 3a). CCK-8 assay showed upregulation of MIR-382 inhibited HT29 cell proliferation (Fig. 3b). Wound-healing assay showed migration ability of HT29 cells transfected with MIR-382 mimic was downregulated compared with those transfected with NC (Fig. 3c). We also investigated the expression of four epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers in synthetic miRNAs transfected cell line. We found E-Cadherin was significantly downregulated; however, the expression of N-Cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail was remarkedly upregulated in MIR-382 inhibitor transfected cells (Fig. 3d). However, E-Cadherin expression was upregulated but the N-Cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail expression was downregulated at cells transfected with MIR-382 mimic (Fig. 3d). These results demonstrated that MIR-382 functions as tumor suppressor in CRC.

Overexpression of MIR-382 inhibits cell proliferation and migration. a The expression of MIR-382 in HT29 cell lines with synthetic miRNAs transfection. b CCK-8 assay was performed to measure cell proliferation in HT29 cell line after synthetic miRNAs transfection. c Wound-healing assay was performed to measure cell migration in HT29 cell line after synthetic miRNAs transfection. d Western blot was conducted to measure the expression of E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail. (***P < 0.001) MIR-382: microRNA-382; NC: negative control; CCK-8: cell counting kit-8; OD 450: optical density at 450 nm

SP1 was a target of MIR-382 in CRC

The results of TargetScan demonstrated that SP1 was a potential target of MIR-382 (Fig. 4a). Meanwhile, we found SP1 expression was significantly reduced in HT29 cells with MIR-382 mimic transfection (Fig. 4b). Subsequently, luciferase activity reporter assay was conducted to validate the connection between MIR-382 and SP1. It was found that MIR-382 mimic inhibited the luciferase activity of cells transfected with pMIR-SP1-3′-UTR Wt but not pMIR-SP1-3′-UTR Mut (Fig. 4c). Finally, we found an inversely correlation between MIR-382 and SP1 in CRC tissues (Fig. 4d). These results revealed that SP1 was a direct target of MIR-382.

MIR-382 directly target SP1 in CRC. a The predicted MIR-382 binding site within Sp2 3′-UTR and its mutated version. b MIR-382 mimic inhibited the expression of SP1 in HT29 cells. c MIR-382 mimic inhibited luciferase activity of cells transfected with pMIR-SP1-3′-UTR Wt but not pMIR-SP1-3′-UTR Mut. d Correlation between MIR-382 and SP1 expression in CRC tissues. (***P < 0.001, ns: not significant) MIR-382: microRNA-382; NC: negative control; SP1: specific protein 1; Wt: wild-type; mut: mutant; CRC: colorectal cancer; UTR: untranslated region

SP1 knockdown reduces the suppressive effects of MIR-382 on CRC cells

To determine the critical mediator of MIR-382 induced effects on cell proliferation and migration, loss-of-function experiment was conducted. We found si-SP1 transfection significantly reduced SP1 expression in HT29 cells (Fig. 5a). As shown in Fig. 5b, the knockdown of SP1 partially abrogated the stimulation effect of MIR-382 inhibitor on cell proliferation. Wound-healing assay showed that si-SP1 abolished the stimulation effects of MIR-382 inhibitor on cell migration (Fig. 5c). In the meantime, we found knockdown of SP1 increased E-Cadherin expression but decreased the expression of N-Cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail (Fig. 5d).

Knockdown of SP1 inhibits cell proliferation and migration. a The expression of SP1 in HT29 cell lines with synthetic siRNAs transfection. b CCK-8 assay was performed to measure cell proliferation in HT29 cell line with synthetic siRNAs or miRNAs transfection. c Wound-healing assay was performed to measure cell migration in HT29 cell line with synthetic siRNAs or miRNAs transfection. d Western blot was conducted to measure the expression of E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail. (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, ns: not significant) MIR-382: microRNA-382; NC: negative control; SP1: specific protein 1; si-SP1: siRNA targeting SP1; CCK-8: cell counting kit-8; OD 450: optical density at 450 nm

Discussion

Extensive efforts to develop cancer treatment methods have been made but cancer is still a global health burden [1, 16, 17]. Emerging evidence showed miRNAs were deeply participated in human cancers [18]. MIR-382 was found act as tumor suppressor and involved in the pathogenesis of various human cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and osteosarcoma [19,20,21]. For instance, Zhang et al. reported MIR-382 is able to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by targeting Golgi Membrane Protein 1 [19]. Also, they reported low MIR-382 expression is an independent prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma [19]. Moreover, Tan et al. found MIR-382 could inhibit ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through regulating receptor tyrosine kinase orphan receptor 1 [20]. However, the precise mechanism of MIR-382 in regulating CRC progression remains need further investigations.

In this study, we examined MIR-382 expression in CRC and we found MIR-382 expression was significantly reduced in CRC tissues and cell lines. Furthermore, we found low MIR-382 expression indicated poorer 5-year overall survival of CRC patients. Given MIR-382 expression was downregulated in CRC tissues and cell lines, we therefore interested to investigate the effects of MIR-382 on CRC cell proliferation and migration. Functional assays demonstrated that MIR-382 overexpression inhibits cell proliferation and migration in vitro. EMT is considered as key step for invasion and metastasis [22]. We showed MIR-382 overexpression decreased the expression of mesenchymal markers including N-Cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail but increased the expression of epithelial marker E-Cadherin. These results revealed that MIR-382 functions as a tumor suppressor in CRC.

The above results provided us a preliminarily understanding of the critical role of MIR-382 in CRC, however, the precise mechanism behind these effects were still unknown. By utilizing bioinformatic analysis and western blot, we found SP1 was a direct target of MIR-382. Interestingly, SP1 was previously demonstrated to be overexpressed in CRC and correlated with CRC metastasis [10]. Also, it was established that SP1 is involved in the growth and progression of tumors [5, 10]. Therefore, it is interesting to investigate whether SP1 was a mediator for the inhibitory role of MIR-382 in CRC. Our results demonstrated that the knockdown of SP1 abolished the effects of MIR-382 on cell proliferation and migration. We also searched the validated targets of MIR-382 in miRTarBase (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/php/index.php) and found SP1 was not included in the current version database. Therefore, our study may provide evidence that SP1 was a novel target for MIR-382.

Conclusions

In conclusions, our results demonstrated that MIR-382 acts as a tumor suppressive miRNA in CRC progression. MIR-382 inhibited CRC proliferation and migration through targeting SP1. Taken together, these findings highlighted the importance of MIR-382/SP1 axis in the progression of CRC and may provide novel targets for CRC treatment.

Abbreviations

- MIR-382 :

-

microRNA-382

- CRC:

-

colorectal cancer

- RT-qPCR:

-

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- CCK-8:

-

cell counting kit-8

- NC:

-

negative control

- SP1:

-

specific protein 1

- Wt:

-

wild type

- Mut:

-

mutant

- UTR:

-

untranslated region

- si-SP1:

-

small interfering RNA targeting SP1

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(3):177–93.

Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, Anderson RN, Jemal A, Schymura MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Seeff LC, van Ballegooijen M, Goede SL, Ries LA. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544–73.

Sung JJ, Ng SC, Chan FK, Chiu HM, Kim HS, Matsuda T, Ng SS, Lau JY, Zheng S, Adler S, Reddy N, Yeoh KG, Tsoi KK, Ching JY, Kuipers EJ, Rabeneck L, Young GP, Steele RJ, Lieberman D, Goh KL, Asia Pacific Working Group. An updated Asia Pacific Consensus Recommendations on colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2015;64(1):121–32.

Beishline K, Azizkhan-Clifford J. SP1 and the “hallmarks of cancer”. FEBS J. 2015;282(2):224–58.

Kadonaga JT, Courey AJ, Ladika J, Tjian R. Distinct regions of SP1 modulate DNA binding and transcriptional activation. Science. 1998;242:1566–70.

Liu Y, Du Y, Hu X, Zhao L, Xia W. Up-regulation of ceRNA TINCR by SP1 contributes to tumorigenesis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):367.

Su F, Geng J, Li X, Qiao C, Luo L, Feng J, Dong X, Lv M. SP1 promotes tumor angiogenesis and invasion by activating VEGF expression in an acquired trastuzumab-resistant ovarian cancer model. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(5):2677–84.

Yin P, Zhao C, Li Z, Mei C, Yao W, Liu Y, Li N, Qi J, Wang L, Shi Y, Qiu S, Fan J, Zha X. SP1 is involved in regulation of cystathionine gamma-lyase gene expression and biological function by PI3K/Akt pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cell Signal. 2012;24(6):1229240.

Bajpai R, Nagaraju GP. Specificity protein 1: its role in colorectal cancer progression and metastasis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;113:1–7.

Nam EH, Lee Y, Zhao XF, Park YK, Lee JW, Kim S. ZEB2-SP1 cooperation induces invasion by upregulating cadherin-11 and integrin alpha5 expression. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(2):302–14.

Waby JS, Chirakkal H, Yu C, Griffiths GJ, Benson RS, Bingle CD, Corfe BM. SP1 acetylation is associated with loss of DNA binding at promoters associated with cell cycle arrest and cell death in a colon cell line. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:275.

Qian M, Gong H, Yang X, Zhao J, Yan W, Lou Y, Peng D, Li Z, Xiao J. MicroRNA-493 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma cells through directly targeting specificity protein 1. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(5):8149–56.

Li Y, Wu Y, Sun Z, Wang R, Ma D. MicroRNA-376a inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in glioblastoma multiforme by directly targeting specificity protein 1. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(1):1583–90.

Lv L, Wang X. MicroRNA-296 targets specificity protein 1 to suppress cell proliferation and invasion in cervical cancer. Oncol Res. 2018;26(5):775–83.

Tang DY, Zhao X, Yang T, Wang C. Paclitaxel prodrug based mixed micelles for tumor-targeted chemotherapy. RSC Adv. 2018;8(1):380–9.

Wang C, Chen SQ, Wang YX, Liu XR, Hu FQ, Sun JH, Yuan H. Lipase-triggered water-responsive “Pandora’s Box” for cancer therapy: toward induced neighboring effect and enhanced drug penetration. Adv Mater. 2018;30(14):1706407.

Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–66.

Zhang S, Ge W, Zou G, Yu L, Zhu Y, Li Q, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Xu T. MIR-382 targets GOLM1 to inhibit metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma and its down-regulation predicts a poor survival. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8(1):120–31.

Tan H, He Q, Gong G, Wang Y, Li J, Wang J, Zhu D, Wu X. MIR-382 inhibits migration and invasion by targeting ROR1 through regulating EMT in ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2016;48(1):181–90.

Xu M, Jin H, Xu CX, Sun B, Song ZG, Bi WZ, Wang Y. MIR-382 inhibits osteosarcoma metastasis and relapse by targeting Y box-binding protein 1. Mol Ther. 2015;23(1):89–98.

Wang J, Ma Z, Carr SA, Mertins P, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Chan DW, Ellis MJ, Townsend RR, Smith RD, McDermott JE, Chen X, Paulovich AG, Boja ES, Mesri M, Kinsinger CR, Rodriguez H, Rodland KD, Liebler DC, Zhang B. Proteome profiling outperforms transcriptome profiling for coexpression based gene function prediction. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16(1):121–34.

Authors’ contributions

YPR was responsible for the study design and the acquisition of data, YPR, HZ and PJ undertook data analysis and performed the functional experiments. YPR, HZ and PJ undertook project design and manuscript revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, Y., Zhang, H. & Jiang, P. MicroRNA-382 inhibits cell growth and migration in colorectal cancer by targeting SP1. Biol Res 51, 51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-018-0200-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-018-0200-9