Abstract

Background

Targeted radionuclide therapy (TRT) is gaining importance. For TRT to be also used as adjuvant therapy or for treating minimal residual disease, there is a need to increase the radiation dose to small tumours. The aim of this in silico study was to compare the performances of 161Tb (a medium-energy β− emitter with additional Auger and conversion electron emissions) and 177Lu for irradiating single tumour cells and micrometastases, with various distributions of the radionuclide.

Methods

We used the Monte Carlo track-structure (MCTS) code CELLDOSE to compute the radiation doses delivered by 161Tb and 177Lu to single cells (14 μm cell diameter with 10 μm nucleus diameter) and to a tumour cluster consisting of a central cell surrounded by two layers of cells (18 neighbours). We focused the analysis on the absorbed dose to the nucleus of the single tumoral cell and to the nuclei of the cells in the cluster. For both radionuclides, the simulations were run assuming that 1 MeV was released per μm3 (1436 MeV/cell). We considered various distributions of the radionuclides: either at the cell surface, intracytoplasmic or intranuclear.

Results

For the single cell, the dose to the nucleus was substantially higher with 161Tb compared to 177Lu, regardless of the radionuclide distribution: 5.0 Gy vs. 1.9 Gy in the case of cell surface distribution; 8.3 Gy vs. 3.0 Gy for intracytoplasmic distribution; and 38.6 Gy vs. 10.7 Gy for intranuclear location. With the addition of the neighbouring cells, the radiation doses increased, but remained consistently higher for 161Tb compared to 177Lu. For example, the dose to the nucleus of the central cell of the cluster was 15.1 Gy for 161Tb and 7.2 Gy for 177Lu in the case of cell surface distribution of the radionuclide, 17.9 Gy for 161Tb and 8.3 Gy for 177Lu for intracytoplasmic distribution and 47.8 Gy for 161Tb and 15.7 Gy for 177Lu in the case of intranuclear location.

Conclusion

161Tb should be a better candidate than 177Lu for irradiating single tumour cells and micrometastases, regardless of the radionuclide distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Targeted radionuclide therapy (TRT) uses radiopharmaceuticals to target and irradiate tumour cells [1]. TRT was introduced several decades ago with the use of 131I for treating thyroid cancer. More recently, the potential for TRT of several other radionuclides, including β− emitters as well as Auger electron emitters, has been explored [2, 3]. In particular, 90Y and 177Lu have been linked to biological vectors and found various therapeutic applications, including targeted treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, peptide receptor TRT of neuroendocrine tumours and PSMA ligands TRT of metastatic prostate cancer [1, 4–6].

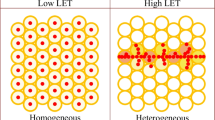

TRT faces two challenges: the heterogeneity found in large tumours and the energy escape from very small tumours. Heterogeneity can be addressed by using medium- or high-energy β− emitters to increase the cross-dose to cold areas. However, these medium- or high-energy β− emitters deliver most of the radiation dose outside of the targeted cells and therefore can fall short of the required dose to eradicate micrometastases and single tumour cells. Indeed, there is an optimal tumour size for “curability” associated to each radionuclide [7–10]. For instance, it is suggested that the β− particles emitted by 90Y (mean energy = 933 keV) are more effective against large tumours (28–42 mm), while the β− emissions of 177Lu (mean energy = 133 keV) would be more adapted for eradicating tumours of about 1.2–3 mm diameter [7]. The mean energy of 177Lu is, however, still too high when considering micrometastases or single tumour cells, which can be undertreated and be a source of relapse. For an electron energy released per unit of volume of 1 MeV per μm3, a 2-mm sphere would receive 128 Gy, while a 200- μm sphere would receive 42 Gy, and a 20- μm sphere would receive only 6.6 Gy [10]. Theoretical dose calculations suggested that 161Tb may outperform 177Lu [10–12]. The superiority of 161Tb over 177Lu has been observed in cell survival studies, as well as in studies on mice bearing small tumour xenografts [13–15]. 161Tb has many intrinsic properties that make it very interesting for TRT [16]. In addition to its medium-energy β− spectrum (mean energy = 154 keV), 161Tb emits a much higher number of very low-energy Auger electrons (AE) than 177Lu, as well as conversion electrons (CE) with low energy (mostly ≤ 40 keV). These low-energy electrons have high linear energy transfer and confer 161Tb an advantage over 177Lu up to about 30 μm from the decay site [12]. Low-energy electrons emitted by 161Tb have been shown to increase the local dose in tumours without exacerbating renal damage [17]. 177Lu and 161Tb share chemical properties as radiolanthanides; thus, similar radiolabelling techniques can be used for both [13, 16]. Moreover, no-carrier-added 161Tb can be produced via the 160Gd(n, γ)161Gd →161Tb nuclear reaction in the quantity and quality needed for clinical applications [16, 18]. 161Tb emits a small percentage of photons that can be useful for post-therapy SPECT imaging, as is the case with 177Lu. Finally, 161Tb is compatible with the concept of theranostics, i.e. a diagnostic match may be found among other terbium radioisotopes allowing imaging before therapy, while 177Lu lacks a useful companion diagnostic radionuclide [19, 20].

In previous works [10, 12], we evaluated the absorbed doses from uniform distributions of 161Tb in water-density spheres of different sizes and compare it to 177Lu, 67Cu and 47Sc. Following energy normalisation, it was found that doses delivered by 161Tb per MeV released were similar to the doses delivered by the other radionuclides for spheres > 1 mm, but an advantage emerged for 161Tb for spheres < 1 mm, that progressively increased as sphere size decreased.

In the current work, we extend the comparison between 161Tb and 177Lu to take into account the subcellular distribution of the radionuclide. We assessed the radiation dose to the nucleus of a single cell for various specific subcellular distributions of the radionuclides. We also studied the absorbed doses to the nuclei of cells within a small cell cluster mimicking a micrometastasis.

Methods

We computed the absorbed doses from simulations performed with the Monte Carlo track-structure (MCTS) code CELLDOSE, which has been described and validated in previous publications [21, 22].

The decay characteristics of 177Lu and 161Tb were taken from the ICRP Publication 107 [23] and are presented in Table 1. The whole β− spectra were taken into account as well as all CE and AE emissions with probability greater than 0.0001. Photons were neglected.

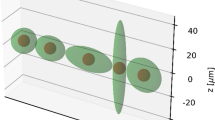

The cell was modelled as a spherical volume of 14 μm diameter, with a membrane of 10 nm thickness and a centred spherical nucleus of 10 μm diameter (see Fig. 1a). All cell compartments were assumed to contain unit density water. The energy transferred by each electron to the medium was scored event-by-event until the electron’s energy fell below 7.4 eV (the electronic excitation threshold of the water molecule), in which case the remaining energy was considered as locally absorbed. Each simulation consisted of 1 million decays of the selected radionuclide (177Lu or 161Tb). We considered either of the following specific distributions of the radionuclide: only on the cell surface, only in the cytoplasm, only within the nucleus, and a uniform distribution in the whole cell. Because 177Lu and 161Tb do not have the same electron energy per decay (see Table 1), the absorbed doses were normalised considering that 1 MeV was released per μm3 [10, 12]. This assumption means that for our cell of 1436 μm3 volume, 1436 MeV were released from one of the regions of interest defined above. In our simulations, we assessed the absorbed dose to the nucleus, as the main critical target for radiation-induced cell death.

For the cluster, we considered cells arranged in a simple cubic structure model, as depicted in Fig. 1b. The cluster consisted of (i) a central cell, (ii) 6 cells forming the first neighbourhood in direct contact with the central cell and (iii) 12 cells forming the second neighbourhood. Given the symmetry of the system, the absorbed dose to a cell in a given neighbourhood is representative of the dose received by the other cells of that neighbourhood. Each cell of the cluster has the same dimensions as the isolated cell described above. All cells were assumed to be labelled in the same way, i.e. to contain a uniform distribution of the radionuclide in one of the specific regions of interest defined above (cell surface, or cytoplasm, or nucleus, or the whole cell). We assessed the radiation dose to the nucleus of the central cell, as well as to the nuclei of cells of the first and second neighbourhoods. In each case, we provide the self-dose, the cross-dose and the total dose. We did not simulate additional neighbourhoods: indeed, our previous results have shown that the superiority of 161Tb mainly resides in the emission of low-energy electrons [10, 12]. Let us note that all dose contributions to the cell nuclei of the cluster are due to electrons emitted from a distance equal to or less than the maximum diameter of our cluster (∼ 50 μm).

Results

Single cell

We report in Table 2 the doses delivered by 177Lu or 161Tb. The absorbed dose to the nucleus of the single cell is lowest when the radionuclide is located on the cell surface, and highest when it is incorporated in the nucleus itself. However, regardless of the distribution of the radionuclide, the dose delivered by 161Tb is higher than the dose delivered by 177Lu. In order to facilitate the comparison between the two radionuclides, we also provide the enhancement factor, i.e. the absorbed dose ratio 161Tb/177Lu. As seen in Table 2 the enhancement factor is 2.6 in the case of cell surface location and up to 3.6 in case of intranuclear location.

Cell cluster

We report in Table 3 the absorbed dose to nucleus of the central cell within the cluster. As compared to the situation of the single cell (see Table 2), the addition of the 18 neighbouring cells increases the dose, regardless of the distribution of the radionuclide and more obviously so in case of cell surface distribution. Here again, it can be seen that the doses delivered by 161Tb are consistently higher than those delivered by 177Lu. More specifically, the enhancement factor 161Tb/177Lu is 2.1 in case of cell surface distribution and 3 in case of intranuclear location (see Table 3).

We also estimated the dose to the nuclei of the cells of the first and second neighbourhoods. We give the absorbed dose as well as the percentage contribution of the self-dose (see Table 4). The relative contribution of self-dose increases as we move from the central cell to the first and second neighbourhoods. It also increases as we move from a cell surface distribution to an intranuclear distribution. For example, in the case of 161Tb, the self-dose contribution varies from 33% up to 90%. As Table 4 also shows, the dose from 161Tb is consistently higher than that of 177Lu, regardless of the distribution of the radionuclide and the position of the cell in the cluster.

Discussion

Cancer recurrence may occur months or years after surgery and is related to residual isolated tumour cells or micrometastases [24–26]. TRT can be very helpful as adjuvant therapy to eradicate such residual tumoral tissue. Adjuvant 131I therapy has been widely used in thyroid cancer patients. The concept of treating minimal residual disease with TRT has also been extended to other tumours [4, 27], for example as consolidation after chemotherapy in follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma [4]. However, the radionuclides currently used for TRT in clinical practice have been designed for treating advanced disease, usually in patients with macrometastases and might not be optimal for adjuvant therapy. Indeed, with conventional radionuclides such as 90Y and 177Lu, most of the released energy would escape from single tumour cells or micrometastases, leading to reduced efficacy and increased toxicity. Other radionuclides may be more appropriate [7, 10, 12]. Among these radionuclides are alpha emitters and AE emitters. On the other hand, 161Tb can be of particular interest as it combines a medium-energy β− spectrum similar to 177Lu with multiple emissions of AE and low-energy CE (see Table 1). These characteristics should allow using 161Tb in conventional situations of advanced disease, but also for adjuvant therapy. 161Tb has gained attention as an interesting alternative to 177Lu. The increased therapeutic efficacy of 161Tb over 177Lu has been demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo studies [13–15], and clinical trials are currently being planned [15, 20].

In the present work, we used the MCTS code CELLDOSE to compute the radiation dose to the nucleus of isolated tumour cells and cells in a tumour cluster resulting from a specific distribution of the radionuclides in cell compartments. In each simulation, we considered 1436 MeV released (1 MeV per μm3, see Fig. 1). Our study shows that the radiation dose delivered to the nucleus of a single tumour cell, and to the nucleus of any cell in a small cluster, is always higher with 161Tb than for 177Lu, regardless of the distribution of the radionuclide. Furthermore, for both radionuclides, the absorbed dose to the cell nucleus increases progressively as we move from a cell surface, to an intracytoplasmic and to an intranuclear distribution of the radionuclide. The radiation doses and enhancement factors for 161Tb and 177Lu are shown in Table 2 for the single cell and in Tables 3 and 4 for the tumour cluster. Figure 2 summarizes these results. These findings support the view that 161Tb may be a better choice than 177Lu for irradiating single tumour cells and micrometastases. On the other hand, it should be noted that even large tumours may benefit from a treatment with 161Tb. Indeed, large tumours are known to suffer from significant heterogeneity (necrosis, fibrosis, stromal tissue) that reduces the efficacy of cross-doses. In this context, 161Tb may provide a local boost to labelled tumoral cells because of the significant self-dose component offered by low-energy electrons.

Table 4 gives information on the percentage contribution of the self-dose in the cluster.

As it can be deduced from Fig. 2 and Tables 2 and 3, the incorporation of 161Tb into the cell nucleus would be of great interest to fully take advantage of its superiority over 177Lu. The transport of a radionuclide into the cell nucleus is a complex task, since the radiopharmaceutical must be designed to overcome the biological barriers imposed by both the cell membrane and the nuclear envelope [28]. Many teams are working to enhance nuclear targeting of radiopharmaceuticals, either for molecular imaging of intracellular proteins or TRT with AE emitters [28]. Specific dosimetry to DNA that might result from DNA-targeting molecules labelled with 161Tb has not been assessed in the present study.

Additional proof on energy deposit in vivo, with comparison between 161Tb and 177Lu, would require experimental microdosimetry data at cellular and subcellular level, using techniques such as beta imagers or micro-autoradiography [29–31]. On the other hand, the size of cell and nucleus influences simulations’ outcome and absorbed doses in cell compartments. In the present simulation, the cell and nucleus diameters were of 14 and 10 μm, respectively, which results in the nucleus to occupy ∼ 36% of the total cell volume. This value is higher than in normal cells, where the average diameter of the nucleus is approximately 6 μm and the nucleus occupies about 10% of the total cell volume [32]. Morphologically, the cancerous cell is characterized by a large nucleus, while the cytoplasm is scarce. Many cancers are diagnosed and staged based on graded increases in nuclear size [33]. The ratio of nucleus volume to cell volume we chose for our simulation is in line with other works. For example, in the work by Goddu et al. [34], the spherical cells have a diameter of 10 μm and contain a concentric spherical nucleus of 8 μm diameter, which results in a V nucleus/V cell of ∼ 50%. In the recent study by Tamborino et al. [35] with experiments performed on human osteosarcoma cells, the V nucleus/V cell was estimated as ∼ 30% based on 4Pi confocal microscopy.

Finally, it is important to stress that changing a radiometal can lead to substantial and sometimes unpredictable modifications in the affinity of a ligand to its receptor [36–38]. As lanthanides, terbium and lutetium share very similar chemistry. Chelators such as DOTA are adequate for both radionuclides and affinity of some labelled molecules looked similar [13–15], but this needs to be further confirmed with additional radiopharmaceuticals.

Conclusion

161Tb associates the traditional advantages of a medium-energy β− emission spectrum with the additional benefit of a high localised dose provided by conversion and Auger electrons. This allows a higher dose to the targeted cells and their immediate neighbours. 161Tb would always deliver higher absorbed doses than 177Lu in single tumour cells and micrometastases regardless of the cellular distribution of the radionuclide.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Auger electrons

- CE:

-

Conversion electrons

- DOTA:

-

Dodecane tetraacetic acid

- MCTS:

-

Monte Carlo track-structure

- PSMA:

-

Prostate-specific membrane antigen

- SPECT:

-

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- TRT:

-

Targeted radionuclide therapy.

References

Knapp FF, Dash A. Radiopharmaceuticals for therapy. New Delhi: Springer; 2016.

Lanconelli N, Pacilio M, Lo Meo S, Botta F, Di Dia A, Aroche AT, Pérez MAC, Cremonesi M. A free database of radionuclide voxel S values for the dosimetry of nonuniform activity distributions. Phys Med Biol. 2012; 57:517–33. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/57/2/517.

Reiner D, Blaickner M, Rattay F. Discrete beta dose kernel matrices for nuclides applied in targeted radionuclide therapy (TRT) calculated with MCNP5. Med Phys. 2009; 36:4890–6. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3231995.

Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, Botto B, Rohatiner AZ, Salles G, Soubeyran P, Tilly H, Bischof-Delaloye A, van Putten WL, Kylstra JW, Hagenbeek A. 90Yttrium-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation of first remission in advanced-stage follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: updated results after a median follow-up of 7.3 years from the international, randomized, phase III first-line indolent trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:1977–83. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.45.6400.

Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, Mittra E, Kunz PL, Kulke MH, Jacene H, Bushnell D, O’Dorisio TM, Baum RP, Kulkarni HR, Caplin M, Lebtahi R, Hobday T, Delpassand E, Van Cutsem E, Benson A, Srirajaskanthan R, Pavel M, Mora J, Berlin J, Grande E, Reed N, Seregni E, Oberg K, Lopera Sierra M, Santoro P, Thevenet T, Erion JL, Ruszniewski P, Kwekkeboom D, Krenning E. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-DOTATATE for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:125–35. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1607427.

Hofman MS, Violet J, Hicks RJ, Ferdinandus J, Thang SP, Akhurst T, Iravani A, Kong G, Ravi Kumar A, Murphy DG, Eu P, Jackson P, Scalzo M, Williams SG, Sandhu S. [ 177Lu]-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (LuPSMA trial): a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018; 19:825–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30198-0.

O’Donoghue J, Bardiès M, Wheldon T. Relationships between tumor size and curability for uniformly targeted therapy with beta-emitting radionuclides. J Nucl Med. 1995; 36:1902–9.

de Jong M, Valkema R, Jamar F, Kvols LK, Kwekkeboom DJ, Breeman WA, Bakker WH, Smith C, Pauwels S, Krenning EP. Somatostatin receptor-targeted radionuclide therapy of tumors: preclinical and clinical findings. Semin Nucl Med. 2002; 32:133–40. https://doi.org/10.1053/snuc.2002.31027.

de Jong M, Breeman WA, Valkema R, Bernard BF, Krenning EP. Combination radionuclide therapy using 177Lu and 90Y-labeled somatostatin analogs. J Nucl Med. 2005; 46:13.

Hindié E, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Quinto MA, Morgat C, Champion C. Dose deposits from 90Y, 177Lu, 111In, and 161Tb in micrometastases of various sizes: Implications for radiopharmaceutical therapy. J Nucl Med. 2016; 57:759–64. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.115.170423.

Uusijärvi H, Bernhardt P, Rösch F, Maecke HR, Forssell-Aronsson E. Electron- and positron-emitting radiolanthanides for therapy: aspects of dosimetry and production. J Nucl Med. 2006; 47:807–14.

Champion C, Quinto MA, Morgat C, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hindié E. Comparison between three promising β-emitting radionuclides, 67Cu, 47Sc and 161Tb, with emphasis on doses delivered to minimal residual disease. Theranostics. 2016; 6:1611–8. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.15132.

Müller C, Reber J, Haller S, Dorrer H, Bernhardt P, Zhernosekov K, Türler A, Schibli R. Direct in vitro and in vivo comparison of 161Tb and 177Lu using a tumour-targeting folate conjugate. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014; 41:476–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-013-2563-z.

Grünberg J, Lindenblatt D, Dorrer H, Cohrs S, Zhernosekov K, Köster U, Türler A, Fischer E, Schibli R. Anti-L1CAM radioimmunotherapy is more effective with the radiolanthanide terbium-161 compared to lutetium-177 in an ovarian cancer model. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014; 41:1907–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-014-2798-3.

Müller C, Umbricht CA, Gracheva N, Tschan VJ, Pellegrini G, Bernhardt P, Zeevaart JR, Köster U, Schibli R, van der Meulen NP. Terbium-161 for PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019; 46:1919–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-019-04345-0.

Lehenberger S, Barkhausen C, Cohrs S, Fischer E, Grünberg J, Hohn A, Köster U, Schibli R, Türler A, Zhernosekov K. The low-energy β− and electron emitter 161Tb as an alternative to 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy. Nucl Med Biol. 2011; 38:917–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.007.

Haller S, Pellegrini G, Vermeulen C, van der Meulen NP, Köster U, Bernhardt P, Schibli R, Müller C. Contribution of Auger/conversion electrons to renal side effects after radionuclide therapy: preclinical comparison of 161Tb-folate and 177Lu-folate. EJNMMI Res. 2016; 6:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-016-0171-1.

Gracheva N, Müller C, Talip Z, Heinitz S, Köster U, Zeevaart JR, Vögele A, Schibli R, van der Meulen NP. Production and characterization of no-carrier-added 161Ttb as an alternative to the clinically-applied 177Lu for radionuclide therapy. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem. 2019; 4:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41181-019-0063-6.

Müller C, Zhernosekov K, Köster U, Johnston K, Dorrer H, Hohn A, van der Walt NT, Türler A, Schibli R. A unique matched quadruplet of terbium radioisotopes for PET and SPECT and for α- and β− radionuclide therapy: an in vivo proof-of-concept study with a new receptor-targeted folate derivative. J Nucl Med. 2012; 53:1951–9. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.112.107540.

Zhang J, Singh A, Kulkarni HR, Schuchardt C, Müller D, Wester H-J, Maina T, Rösch F, van der Meulen NP, Müller C, Mäcke H, Baum RP. From bench to bedside—the bad Berka experience with first-in-human studies. Semin Nucl Med. 2019; 49:422–37. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2019.06.002.

Champion C, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hindié E. Celldose: A Monte Carlo code to assess electron dose distribution S values for 131i in spheres of various sizes. J Nucl Med. 2008; 49:151–7. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.107.045179.

Hindié E, Champion C, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Rubello D, Colas-Linhart N, Ravasi L, Moretti J-L. Calculation of electron dose to target cells in a complex environment by Monte Carlo code "CELLDOSE". Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009; 36:130–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-0893-z.

International Commission on Radiological Protection. Nuclear Decay Data for Dosimetric Calculations. ICRP Publication 107. Ann. ICRP2008;38.

Hurst RE, Bastian A, Bailey-Downs L, Ihnat MA. Targeting dormant micrometastases: rationale, evidence to date and clinical implications. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016; 8:126–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834015624277.

Cortés-Hernández LE, Eslami-S Z, Pantel K, Alix-Panabières C. Molecular and functional characterization of circulating tumor cells: from discovery to clinical application. Clin Chem. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2019.303586.

Pantel K, Alix-Panabières C. Liquid biopsy and minimal residual disease — latest advances and implications for cure. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019; 16:409–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-019-0187-3.

Sahlmann C-O, Homayounfar K, Niessner M, Dyczkowski J, Conradi L-C, Braulke F, Meller B, Beißbarth T, Ghadimi BM, Meller J, Goldenberg DM, Liersch T. Repeated adjuvant anti-CEA radioimmunotherapy after resection of colorectal liver metastases: safety, feasibility, and long-term efficacy results of a prospective phase 2 study. Cancer. 2017; 123:638–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30390.

Cornelissen B. Imaging the inside of a tumour: a review of radionuclide imaging and theranostics targeting intracellular epitopes. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2014; 57:310–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlcr.3152.

Yorke ED, Williams LE, Demidecki AJ, Heidorn DB, Roberson PL, Wessels BW. Multicellular dosimetry for beta-emitting radionuclides: autoradiography, thermoluminescent dosimetry and three-dimensional dose calculations. Med Phys. 1993; 20:543–50. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.597050.

Schollhammer R, de Clermont Gallerande H, Yacoub M, Quintyn Ranty M-L, Barthe N, Vimont D, Hindié E, Fernandez P, Morgat C. Comparison of the radiolabeled PSMA-inhibitor 111In-PSMA-617 and the radiolabeled GRP-R antagonist 111In-RM2 in primary prostate cancer samples. EJNMMI Res. 2019; 9:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-019-0517-6.

Puncher MR, Blower PJ. Radionuclide targeting and dosimetry at the microscopic level: the role of microautoradiography. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994; 21:1347–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02426701.

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular biology of the cell, 4th edn. New York: Garland Science; 2002, p. 197.

Jevtić P, Edens LJ, Vuković LD, Levy DL. Sizing and shaping the nucleus: mechanisms and significance. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014; 28:16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2014.01.003.

Goddu SM, Rao DV, Howell RW. Multicellular dosimetry for micrometastases: dependence of self-dose versus cross-dose to cell nuclei on type and energy of radiation and subcellular distribution of radionuclides. J Nucl Med. 1994; 35:521–30.

Tamborino G, de Saint-Hubert M, Struelens L, Seoane DC, Ruigrok EAM, Aerts, van Cappellen WA, de Jong M, Konijnenberg MW, Nonnekens J. Cellular dosimetry of [ 177Lu]Lu-DOTA-[Tyr 3]octreotate radionuclide therapy: the impact of modeling assumptions on the correlation with in vitro cytotoxicity. EJNMMI Phys. 2020; 7:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-020-0276-5.

Reubi JC, Schär JC, Waser B, Wenger S, Heppeler A, Schmitt JS, Mäcke HR. Affinity profiles for human somatostatin receptor subtypes SST1-SST5 of somatostatin radiotracers selected for scintigraphic and radiotherapeutic use. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000; 27:273–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002590050034.

Fani M, Braun F, Waser B, Beetschen K, Cescato R, Erchegyi J, Rivier JE, Weber WA, Maecke HR, Reubi JC. Unexpected sensitivity of sst 2 antagonists to N-terminal radiometal modifications. J Nucl Med. 2012; 53:1481–9. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.112.102764.

Chastel A, Worm DJ, Alves ID, Vimont D, Petrel M, Fernandez S, Garrigue P, Fernandez P, Hindié E, Beck-Sickinger AG, Morgat C. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a multifunctional neuropeptide-Y conjugate for selective nuclear delivery of radiolanthanides. EJNMMI Res. 2020; 10:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-020-0612-8.

Acknowledgements

This work was achieved and funded within the context of the Laboratory of Excellence TRAIL ANR-10-LABX-57 (INNOVATHER project). Computer time for this study was provided by the computing facilities MCIA (Mésocentre de Calcul Intensif Aquitain) of the Université de Bordeaux and of the Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour. MEAA acknowledges the support of the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT, Mexico), under grant 471688.

Funding

This work was achieved and funded within the context of the Laboratory of Excellence TRAIL ANR-10-LABX-57 (INNOVATHER project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MEAA performed the simulations, processed and analysed the data, prepared the figures and drafted the manuscript. EH, CM and CC planned and supervised the work and made substantial contributions to the final manuscript. AF and MAQ were involved in the design and development of the simulations. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alcocer-Ávila, M.E., Ferreira, A., Quinto, M.A. et al. Radiation doses from 161Tb and 177Lu in single tumour cells and micrometastases. EJNMMI Phys 7, 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-020-00301-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-020-00301-2