Abstract

Hybridization is not always limited to two species; often multiple species are interbreeding. In birds, there are numerous examples of species that hybridize with multiple other species. The advent of genomic data provides the opportunity to investigate the ecological and evolutionary consequences of multispecies hybridization. The interactions between several hybridizing species can be depicted as a network in which the interacting species are connected by edges. Such hybrid networks can be used to identify ‘hub-species’ that interbreed with multiple other species. Avian examples of such ‘hub-species’ are Common Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) and European Herring Gull (Larus argentatus). These networks might lead to the formulation of hypotheses, such as which connections are most likely conducive to interspecific gene flow (i.e. introgression). Hybridization does not necessarily result in introgression. Numerous statistical tests are available to infer interspecific gene flow from genetic data and the majority of these tests can be applied in a multispecies setting. Specifically, model-based approaches and phylogenetic networks are promising in the detection and characterization of multispecies introgression. It remains to be determined how common multispecies introgression in birds is and how often this process fuels adaptive changes. Moreover, the impact of multispecies hybridization on the build-up of reproductive isolation and the architecture of genomic landscapes remains elusive. For example, introgression between certain species might contribute to increased divergence and reproductive isolation between those species and other related species. In the end, a multispecies perspective on hybridization in combination with network approaches will lead to important insights into the history of life on this planet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Traditionally, hybridization has been studied by comparing species pairs, mostly in the context of hybrid zones (Moore 1977; Barton and Hewitt 1985; Harrison 1993). However, hybridization is not always limited to two species, multiple species might interbreed. This multispecies perspective of hybridization raises several questions: How common is multispecies hybridization? How does reproductive isolation evolve between several interacting species? How is the landscape of genomic differentiation shaped by multispecies hybridization? What patterns of gene flow are observed when several species are exchanging genetic material? Birds are an excellent study system to answer these questions. Hybridization is a common phenomenon in this group of animals and several bird species interbreed with more than one species (Price 2008; Ottenburghs et al. 2015). Specifically, the advent of genomic data provides ornithologists with the opportunity to explore the ecological and evolutionary consequences of multispecies hybridization (Kraus and Wink 2015).

How common is multispecies hybridization?

To quantify the incidence of multispecies hybridization in birds, I used records from the Serge Dumont Bird Hybrid Database (http://www.bird-hybrids.com, Additional file 1) for six bird orders that are prone to interbreeding (Ottenburghs et al. 2015): Anseriformes (waterfowl), Galliformes (wildfowl), Charadriiformes (waders, gulls and auks), Piciformes (woodpeckers), Apodiformes (hummingbirds and swifts) and Passeriformes (songbirds). In general, most species hybridized with only one other species, but in each of the six bird orders multispecies hybridization occurs frequently (Fig. 1). In some bird orders, outliers (i.e. species that hybridize with many other species) are clearly visible, namely Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) in Anseriformes, Common Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) in Galliformes, and European Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) in Charadriiformes. Interestingly, these outliers have a large distribution range, providing ample opportunity to interact and potentially interbreed with several other species. It does raise the question whether these species mostly hybridize with closely related species or have hybrids with distantly related species (e.g., intergeneric hybridization) been observed? This question can be addressed by the construction of networks (Proulx et al. 2005; Ottenburghs et al. 2016).

The incidence of multispecies hybridization in six bird orders (Anseriformes, Galliformes, Charadriiformes, Piciformes, Apodiformes and Passeriformes). In general, most species hybridized with only one other species, but in each of the six bird orders multispecies hybridization occurs frequently. Noteworthy outliers are Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos, 39 hybrids, Anseriformes), Common Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus, 14 hybrids, Galliformes) and European Herring Gull (Larus argentatus, 11 hybrids, Charadriiformes). Records based on the Serge Dumont Bird Hybrid Database (http://www.bird-hybrids.com, Additional file 1)

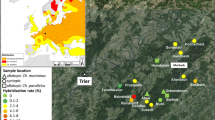

A network is any collection of units potentially interacting as a system. In the simplest case, a network can be represented by a set of uniform nodes (e.g., species) connected by undirected edges that correspond to particular interactions (e.g., hybridization). One could, for instance, connect all the species that are known to have produced hybrid offspring (in nature and captivity). Figure 2 shows such hybrid networks for three bird orders with the highest incidence of hybridization: Anseriformes, Galliformes and Charadriiformes. Analyses of these networks can also identify certain ‘hub-species’ that interbreed with numerous other species. For example, in the Anseriformes, the Mallard has hybridized with at least 39 different species. Most hybridization events concern closely related species, such as the Black Duck (A. superciliosa) in Australia and New Zealand (Taysom et al. 2014); the Hawaiian Duck (A. wylvilliana) on the Hawaiian Islands (Fowler et al. 2009); the American Black Duck (A. rubripes) and the Mottled Duck (A. fulvigula) in North America (Mank et al. 2004; Peters et al. 2014); the Spot-billed Duck (A. zonorhyncha) in Russia and China (Kulikova et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2018); and the Mexican Duck (A. diazi) in Mexico (Lavretsky et al. 2015). However, hybrids between Mallard and more distantly related species have also been documented. For example, Mallard × Red-crested Pochard (Netta rufina) hybrids are relatively common in Central Europe (Randler 2008) and in captivity a hybrid between Mallard and Greylag Goose (Anser anser) has been produced (Poulsen 1950). In the case of Galliformes, Common Pheasant is connected with 14 other species, including species from the subfamilies Tetraoninae (grouse) and Meleagridinae (turkeys). Here, the numerous hybrid interactions of this species can be explained by human-mediated introductions across the globe (Drake 2006), leading to several intergeneric hybrids. In contrast, the European Herring Gull mostly interbreeds with closely related species of the Larus species complex (Sonsthagen et al. 2016). In summary, the hybrid networks provide insights into the patterns of hybridization of these ‘hub-species’: the extensive records of Mallard and Common Pheasant hybrids are the result of interbreeding with both closely and distantly related species, while the European Herring Gull only hybridizes with other closely related gull species.

Examples of hybrid networks for three bird orders: a Anseriformes, b Galliformes and c Charadriiformes. Dots represent species (coloured according to different genera) while edges indicate that hybrid offspring have been observed. Records based on the Serge Dumont Bird Hybrid Database (http://www.bird-hybrids.com, Additional file 1). Drawings used with permission of Handbook of Birds of the World (del Hoyo et al. 2018)

A next step could be to quantify the frequency of hybridization between the different species and adjust the weight of the edges accordingly. This approach is illustrated in Fig. 3 by the Wood-warbler family (Parulidae), a group of passerines that exhibit interesting patterns of multispecies hybridization (Lovette and Bermingham 1999; Willis et al. 2014; Toews et al. 2018). Species that hybridize rarely are connected by thin, black edges, whereas species that hybridize extensively are connected by thick, red edges. The resulting hybrid network reveals five clusters of hybrid interactions. In four species combinations, hybrids are regularly observed, namely Townsend’s Warbler (Setophaga townsendi) × Hermit Warbler (S. occidentalis), Townsend’s Warbler × Black-throated Green Warbler (S. virens), Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera) × Blue-winged Warbler (V. cyanoptera), and Mourning Warbler (Geothlypis philadelphia) × MacGillivray’s Warbler (G. tolmiei). Several of these species pairs have already been assessed genetically (e.g., Vallender et al. 2007; Irwin et al. 2009b; Krosby and Rohwer 2009; Toews et al. 2016). This approach might eventually lead to the formulation of hypotheses, such as which connections are most likely conducive to introgression. For example, species that hybridize regularly have a higher chance of exchanging genetic material. Clearly, these hybrid networks are an important starting point for further exploration of multispecies hybridization.

A hybrid network displaying the incidence of hybridization between different members—genera Geothlypis, Mniotilta, Oreothlypis, Setophaga, and Vermivora—of the Parulidae family. Thin, black edges indicate uncommon hybridization, while thick, red edges indicate extensive hybridization (based on Willis et al. 2014). Bird drawings have been used with permission of Handbook of Birds of the World (del Hoyo et al. 2018) and depict species in bold, namely Townsend’s Warbler (S. townsendi), Black-throated Blue Warbler (S. caerulescens), and Golden-winged Warbler (V. chrysoptera)

A special case of multispecies hybridization concerns three-way hybrids, in which an individual has ancestry of more than two species. For example, Toews et al. (2018) documented how a female hybrid between a Golden-winged Warbler and a Blue-winged Warbler successfully reproduced with a Chestnut-sided Warbler (Setophaga pensylvanica). Another example of a three-way hybrid was described in geese where a hybrid between Swan Goose (Anser cygnoides) and Snow Goose (A. caerulescens) paired up with a Barnacle Goose (Branta leucopsis) and produced offspring (Dreyer and Gustavsson 2009). These observations of ‘hybridizing hybrids’ could provide alternative routes for gene flow between distantly related taxa. However, it remains to be determined how common such three-way hybrids are and how often these cases result in introgression.

Multispecies introgression

Hybridization does not necessarily result in introgression, i.e. the exchange of genetic material from one (sub)species into the gene pool of another by means of hybridization and backcrossing (Arnold 2006). Hybrids might be sterile or unable to attract a partner. The recent developments in avian genomics provide valuable resources to explore whether or not multispecies hybridization leads to introgression (Kraus and Wink 2015; Ottenburghs et al. 2017a). Although most statistical methods have been developed to quantify introgression between two hybridizing species, some approaches can be transferred to a multispecies setting.

Model-based clustering methods, such as STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al. 2000) and ADMIXTURE (Alexander et al. 2009), are often used to visualize the genetic ancestry of individuals. This approach can be used to pinpoint individuals whose genomes show signs of ancestry from multiple sources. For example, based on a STRUCTURE analysis of microsatellites, Thies et al. (2018) uncovered a putative hybrid zone between three subspecies of the Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula). However, the output from these model-based clustering methods should not be taken at face value. Other demographic processes, such as ancestral polymorphisms, bottlenecks or admixture with extinct populations, can produce similar ancestry plots (Novembre 2016; Lawson et al. 2018). For example, the panmictic Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis) is comprised of two divergent mitochondrial lineages. This genetic structure suggests that one mitochondrial variant introgressed from another species. However, detailed analyses revealed that the divergence in mtDNA occurred within the large panmictic population (Benham and Cheviron 2019). That is why it is important to present these results alongside other methods with different assumptions about the underlying model, such as admixture graph (Leppälä et al. 2017) or TreeMix (Pickrell and Pritchard 2012). A recent method, named badMIXTURE, assesses how well different models of admixture fit the observed patterns of genetic ancestry (Lawson et al. 2018). This approach has only been tested on human data, but seems promising to detect multispecies introgression in other taxa.

A useful statistic for detecting multispecies introgression from genetic data is the D-statistic (Durand et al. 2011; Patterson et al. 2012), which was originally developed to check for ancient gene flow between humans and Neanderthals (Green et al. 2010). The D-statistic is calculated in a four taxon setting: three taxa of interest (P1, P2 and P3) and an outgroup (O). Next, ancestral (‘A’) and derived (‘B’) alleles are determined across the genomes of four taxa. Two particular allelic patterns—‘ABBA’ and ‘BABA’—are of interest. Under a scenario of no gene flow, one expects both patterns to occur in equal frequencies. An excess of ‘ABBA’ or ‘BABA’ patterns suggests gene flow between P2 and P3 or P1 and P3, respectively. This method has been extended to more taxa allowing for identifying the direction of gene flow (Eaton and Ree 2013; Pease and Hahn 2015). The D-statistic has been applied to probe patterns of multispecies introgression in Darwin’s finches (Lamichhaney et al. 2015), crows (Vijay et al. 2016), geese (Ottenburghs et al. 2017b) and wheatears (Schweizer et al. 2019).

Another procedure is to look for signs of introgression within the genome. When multiple species have been exchanging genetic material, different parts of the genome are expected to show different evolutionary histories. Reconstructing phylogenetic trees in sliding windows across the genome can thus uncover potential introgressed regions (Gante et al. 2016; Martin and Van Belleghem 2017). This approach is nicely exemplified by a genomic analysis of the Italian Sparrow (Passer italiae), a hybrid species between House Sparrow (P. domesticus) and Spanish Sparrow (P. hispaniolensis) that originated about 10,000 years ago (Hermansen et al. 2011; Elgvin et al. 2017; Ottenburghs 2018; Runemark et al. 2018). In some parts of the genome, Italian Sparrow clusters with House Sparrow, while in other parts it is more closely related to Spanish Sparrow (Elgvin et al. 2017). A complementary approach is to construct local PCA (Principal Component Analysis) plots for each window and consequently explore genomic regions that show concordant patterns (Li and Ralph 2019). Windows with introgressed loci are expected to show lower levels of genetic diversity between hybridizing species. This expectation can be explored with various summary statistics that quantify relative sequence divergence (Fst), absolute sequence divergence (Dxy) and nucleotide diversity (π). Each of these statistics captures a particular aspect of genetic diversity and they should thus be considered jointly in order to discriminate between introgression and other processes, such as linked selection or population bottlenecks (Irwin et al. 2018). The often challenging interpretation of summary statistics can be facilitated by machine learning approaches, in which an algorithm is trained to classify data points into groups (e.g., introgressed vs. non-introgressed loci). For example, a recent study pinpointed introgressed loci between Drosophila simulans and D. sechellia using a machine learning algorithm based on a suite of summary statistics (Schrider et al. 2018). Simulations based on the most likely demographic model were used as training data to learn the algorithm how to recognize introgressed regions from a number of summary statistics. Moreover, Schrider et al. (2018) showed that their machine learning algorithm was able to identify introgressed loci with higher accuracy compared to analyses that rely on single summary statistics. The application of machine learning to population genetic questions is relatively new, but can certainly be implemented in an avian study system (Schrider and Kern 2018).

Detecting introgression between multiple species is only one step in understanding the evolutionary history of a hybridizing species group. To further explore the nature of introgressive hybridization, a modelling approach is often warranted. Isolation-with-migration (IM) models have been developed to infer gene flow parameters between two populations, along with divergence times and effective population sizes (Hey and Nielsen 2004). These models can be extended to multiple populations (Hey 2010) and have been used to explore multispecies introgression in birds. For instance, Reifová et al. (2016) characterized patterns of introgression between three hybridizing Acrocephalus warblers using IM-models. They found evidence for unidirectional gene flow from Reed Warbler (A. scirpaceus) to Marsh Warbler (A. palustris) and from Reed Warbler to Blyth’s Reed Warbler (A. dumetorum). Similarly, a study on three Icterus orioles applied IM-models to describe gene flow patterns (Jacobsen and Omland 2012). They concluded that “only by including all members of this group in the analysis was it possible to rigorously estimate the level of gene flow among these three closely related species.” This indicates the importance of considering multispecies introgression in studies of avian hybridization.

Although IM models are useful to quantify the amount of gene flow between diverging populations, these models cannot be applied to probe more complex models (e.g., with alternating periods of gene flow and isolation). There are several approaches to explore these complex models, ranging from coalescent-based simulators to the use of diffusion equations (Schraiber and Akey 2015). Coalescent-based simulators, such as FastSIMCOAL2 (Excoffier and Foll 2011) and COALHMM (Hobolth et al. 2007), have been applied to infer gene flow between avian (sub)species pairs (e.g., Chattopadhyay et al. 2017; Raposo do Amaral et al. 2018). To my knowledge, these methods have not been applied to a multispecies setting in birds. However, studies in other animal groups indicate that these coalescent-based simulators are promising to detect gene flow between several species (Palkopoulou et al. 2018; Roman et al. 2018). Another modelling approach relies on diffusion models, which use a continuous approximation to the population genetics of a number of individuals evolving in discrete generations. An important underlying assumption is that changes in allele frequencies across generations are small (Gutenkunst et al. 2009). Similar to the coalescent-based methods discussed above, diffusion models have been applied to explore gene flow between two bird species (e.g., Toews et al. 2016; Oswald et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017) but remain to be applied in an avian multispecies setting. Finally, Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) modelling allows for the comparison of multiple scenarios that differ in the amount and timing of gene flow (Beaumont 2010; Csilléry et al. 2010). This approach has been used to infer patterns of gene flow between hybridizing species pairs, such as Ficedula flycatchers (Nadachowska-Brzyska et al. 2013) and Amazilia hummingbirds (Rodríguez-Gómez and Ornelas 2018). Moreover, Nater et al. (2015) compared different scenarios of divergence and gene flow involving four species of black-and-white flycatcher to obtain the most likely species tree, showing that the ABC framework can be extended to multiple species. Each of these approaches comes with its own assumptions (e.g., selective neutrality or small changes in allele frequency) and one should be aware of these when inferring patterns of gene flow (Schraiber and Akey 2015).

The widespread occurrence of multispecies introgression can hinder the estimation of phylogenetic trees, and in some cases a classic bifurcating tree cannot capture the reticulated evolutionary history. Here, a phylogenetic network approach is warranted (Kutschera et al. 2014; Edwards et al. 2016; Mallet et al. 2016; Ottenburghs et al. 2016). A phylogenetic network extends the phylogenetic tree model by allowing for horizontal edges that indicate the exchange of genetic material through introgression. Several methods have been developed to estimate phylogenetic networks from genetic data based on maximum parsimony (Yu et al. 2013), maximum likelihood (Wen and Nakhleh 2017) and Bayesian approaches (Zhu et al. 2018). Available software packages include SplitsTree (Huson 1998), TreeMix (Pickrell and Pritchard 2012), PhyloNetworks (Solís-Lemus et al. 2017), and PhyloNet (Wen et al. 2018). Recently, Bayesian inference of phylogenetic networks was also implemented in the popular phylogenetic software BEAST2 (Zhang et al. 2018). The development of these network methods is still in its infancy and several software packages cannot handle large genomic data sets yet.

The usefulness of taking introgressive hybridization into account when estimating species trees—or networks—is nicely illustrated by a recent study on the Ash-breasted Antbird (Myrmoborus lugubris). This passerine species inhabits the floodplain forests along the Amazonian rivers and is divided into four subspecies: lugubris, berlepschi, femininus and stictopterus. Species tree estimation methods that do not consider hybridization clustered femininus and lugubris, while methods that take hybridization into account revealed that these subspecies are not sister clades. Instead, it turned out that femininus is sister to stictopterus (Thom et al. 2018). In addition, phylogenetic networks can reveal the existence of putative hybrid species. For example, a phylogenomic analysis of geese suggested that Red-breasted Goose (Branta ruficollis) might be of hybrid origin (Ottenburghs et al. 2017b), although this finding needs to be confirmed with further analyses (Ottenburghs 2018). These examples support the notion that avian phylogenetics might shift from trees to networks.

Multispecies hybridization as an evolutionary stimulus?

The advent of genomic data in combination with powerful statistical tools to detect interspecific gene flow has shown that introgression is often an integral component of species diversification and evolution (Rheindt and Edwards 2011; Ottenburghs et al. 2017a). The introgressed genetic material might confer an adaptive advantage to the recipient species, either in the form of increased genetic variation (Hedrick 2013) or the exchange of beneficial alleles (i.e., adaptive introgression, Arnold and Kunte 2017).

In his book on introgressive hybridization, Edgar Anderson (1949) already stated that “raw material brought in by introgression must greatly exceed the new genes produced directly by mutation.” Indeed, apart from standing genetic variation and de novo mutations, introgression is a third source of adaptive variation (Hedrick 2013). The amount of standing genetic variation is a function of past effective population size, while the rate of mutation is a function of present population size. Introgression can be an almost instantaneous source of new adaptive variation or it can fuel the pool of standing genetic variation to be utilized later on. Regardless of the timeframe, adaptive introgression results in the transfer of beneficial alleles and associated phenotypes (Arnold and Kunte 2017). This has been observed in several plant genera (Suarez-Gonzalez et al. 2018), such as Helianthus (Whitney et al. 2006, 2010, 2015), Iris (Martin et al. 2006) and Senecio (Kim et al. 2008). In animals, examples of adaptive introgression include the transfer of mimicry patterns in butterflies (Dasmahapatra et al. 2012; Pardo-Diaz et al. 2012; Enciso-Romero et al. 2017), rodenticide resistance in mice (Song et al. 2011), coat colour in wolves (Anderson et al. 2009) and snowshoe hares (Jones et al. 2018). Finally, adaptive introgression has probably also affected the evolution of humans through gene flow from Neanderthals (Racimo et al. 2015) and Denisovans (Huerta-Sánchez et al. 2014).

In birds, adaptive introgression has been documented as well. In Darwin’s finches, introgressive hybridization probably contributed to the evolution of beak morphology (Lamichhaney et al. 2015). And introgression between Saltmarsh (Ammodramus caudacutus) and Nelson’s Sparrow (A. nelsoni) might have facilitated adaptation to tidal marshes (Walsh et al. 2018). Other candidates for adaptive introgression can be revealed by mito-nuclear discordance, i.e. mitochondrial and nuclear loci that show distinct evolutionary histories (Toews and Brelsford 2012). These patterns are often the outcome of selection on introgressed mitochondrial variants (Bonnet et al. 2017). For example, in the Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata) complex, the Audubon’s Warbler (subspecies auduboni) is probably a hybrid species between Myrtle Warbler (subspecies coronata) and Black-fronted Warbler (subspecies nigrifrons) (Brelsford et al. 2011). As a result of its hybrid origin, the Audobon’s Warbler possesses mtDNA from its two parental species; northern populations have mostly Myrtle-type mtDNA while a small fraction of the southern populations has Black-fronted-type ones. Experiments suggest that the Myrtle-type mitochondria are metabolically more efficient compared to Black-fronted-type ones. Interestingly, Audubon’s Warblers are migratory while Black-fronted Warblers are sedentary. Possibly, the more efficient Myrtle-type mitochondria are beneficial for migratory species and were thus under positive selection in the Audubon’s Warblers (Toews et al. 2014). Adaptive introgression of mtDNA has been suggested in several other avian taxa, but only a few studies assessed selection on the introgressed mtDNA (Irwin et al. 2009a; Dong et al. 2014; Pons et al. 2014; Battey and Klicka 2017; Morales et al. 2017; Shipham et al. 2017).

Species might thus occasionally benefit from introgression. When multiple lineages are interbreeding, the adaptive alleles can flow in from multiple sources. This is nicely illustrated by a recent study on the diversification and domestication of the bovine genus Bos (Wu et al. 2018). Comparing the genomes of members of this genus—which includes taurine cattle, zebu, gayal, gaur, banteng, yak, wisent and bison—revealed complex patterns of introgression between several species. Interestingly, both gayal and bali cattle received genes from zebu cattle through introgressive hybridization. In both cases, the introgressed genes were related to a decrease in anxiety-related behaviour and could have played a role in the domestication of these animals. This example illustrates how multispecies hybridization could facilitate the distribution of potentially adaptive variation. To my knowledge, such a study has not been done in an avian system yet.

The genomic landscape of multispecies hybridization

Hybridization is tightly linked with speciation (Abbott et al. 2013). The origin of new species is mostly seen as the build-up of reproductive isolation and the consequent demise of hybridization (Coyne and Orr 2004). A genomic perspective on this process (Seehausen et al. 2014) in combination with the genic view of speciation (Wu 2001) has revealed that introgression is variable across the genome; some loci are freely exchanged between hybridizing species whereas other loci are not able to cross species boundaries (Payseur 2010). The latter loci are potentially involved in reproductive isolation and might—because they are immune to the homogenizing effects of gene flow—accumulate genetic differentiation over time. The result will be a genomic landscape with ‘islands of differentiation’ within a sea of neutral variation (Wolf and Ellegren 2017). However, these genomic islands can also arise because of processes unrelated to differential gene flow, such as background selection, linked selection or positive selection in allopatry (Cruickshank and Hahn 2014; Burri 2017).

Reproductive isolation mechanisms need not be the same between different hybridizing species. For instance, in the Drosophila melanogaster group, the subspecies biauraria and triauraria are partially reproductively isolated by prezygotic isolation, whereas reproductive isolation between triauraria and quadraria is largely the outcome of postzygotic isolation mechanisms (Coyne and Orr 1997). In birds, such detailed studies have not been performed yet, but the nature of reproductive isolation can be characterized in several avian species groups (Price and Bouvier 2002; Lijtmaer et al. 2003; Campagna et al. 2018). These settings provide an excellent opportunity to study the evolution of reproductive isolation in closely related species. It remains to be determined how species that originate from the same genetic source (i.e. their common ancestor) can develop drastically different reproductive isolation mechanisms and how this consequently shapes the genomic landscape of differentiation. Moreover, introgression between certain species might contribute to increased divergence and reproductive isolation between those species and other related species (Sun et al. 2018).

Most studies characterized genomic landscapes by focusing on two hybridizing species (Wolf and Ellegren 2017; Delmore et al. 2018; Irwin et al. 2018). But studying the evolution of genomic landscapes in the context of multiple hybridizing species can provide important insights. For example, several crow species (Corvus) hybridize in Europe and Asia. Genomic analyses of the European hybrid zone—between Carrion Crow (C. corone) and Hooded Crow (C. cornix)—uncovered genomic islands of differentiation harbouring genes involved in pigmentation and visual perception, suggesting a role in premating isolation (Poelstra et al. 2014). Genomic analyses of the Asian hybrid zone—between Hooded Crow and Eastern Carrion Crow (C. orientalis)—also revealed the clustering of pigmentation genes in genomic islands. However, the location of the genomic islands was specific to each hybrid zone (Vijay et al. 2016). A similar study on three hybridizing woodpecker species—Red-breasted (Sphyrapicus ruber), Red-naped (S. nuchalis) and Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (S. varius)—reported a candidate locus for plumage colour that might be involved in reproductive isolation (Grossen et al. 2016). Contrary to the crow system, however, this locus was not located within a genomic island of differentiation. These examples suggest that the build-up of the genomic landscape is to some extent predictable, but contains a certain amount of contingency.

Conclusions

Hybridization is generally studied in the context of species pairs, although multiple species might be interbreeding. Hence, a multispecies perspective on hybridization is warranted. In birds, an animal group prone to hybridization (Grant and Grant 1992; Price 2008; Ottenburghs et al. 2015), multispecies hybridization is common. However, hybridization does not necessarily result in introgression. A broad range of tools are available to infer interspecific gene flow. The majority of these tools can be transferred to a multispecies setting. Specifically, model-based approaches and phylogenetic networks are promising in the detection and characterization of multispecies introgression. At the moment, we know that introgression is relatively common across the avian Tree of Life, but we do not have an estimate of how often introgression is adaptive (Arnold and Kunte 2017; Ottenburghs et al. 2017a). In addition, when multiple species are interbreeding, the impact on the build-up of reproductive isolation, adaptation to novel environments and the architecture of genomic landscapes remains elusive. Studying hybridization between multiple species and applying new network approaches will lead to important insights into the history of life on this planet.

Availability of data and materials

The data on hybridization in birds are available in Additional file 1, at the Serge Dumont Bird Hybrid Database (http://www.bird-hybrids.com/engine.php?LA=EN) and the Avian Hybrids Project (https://avianhybrids.wordpress.com/).

References

Abbott R, Albach D, Ansell S, Arntzen JW, Baird SJE, Bierne N, Boughman J, Brelsford A, Buerkle CA, Buggs R, et al. Hybridization and speciation. J Evol Biol. 2013;26:229–46.

Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–64.

Anderson E. Introgressive hybridization. New York: Wiley; 1949.

Anderson TM, vonHoldt BM, Candille SI, Musiani M, Greco C, Stahler DR, Smith DW, Padhukasahasram B, Randi E, Leonard JA, et al. Molecular and evolutionary history of melanism in North American gray wolves. Science. 2009;323:1339–43.

Arnold M. Evolution through genetic exchange. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Arnold ML, Kunte K. Adaptive genetic exchange: a tangled history of admixture and evolutionary innovation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2017;32:601–11.

Barton NH, Hewitt GM. Analysis of hybrid zones. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1985;16:113–48.

Battey CJ, Klicka J. Cryptic speciation and gene flow in a migratory songbird species complex: insights from the Red-Eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;113:67–75.

Beaumont MA. Approximate Bayesian computation in evolution and ecology. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2010;41:379–406.

Benham PM, Cheviron ZA. Divergent mitochondrial lineages arose within a large, panmictic population of the Savannah sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis). Mol Ecol. 2019;28:1765–83.

Bonnet T, Leblois R, Rousset F, Crochet P-A. A reassessment of explanations for discordant introgressions of mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. Evolution. 2017;71:2140–58.

Brelsford A, Mila B, Irwin D. Hybrid origin of Audubon’s warbler. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:2380–9.

Burri R. Dissecting differentiation landscapes: a linked selection’s perspective. J Evol Biol. 2017;30:1501–5.

Campagna L, Rodriguez P, Mazzulla JC. Transgressive phenotypes and evidence of weak postzygotic isolation in F1 hybrids between closely related capuchino seedeaters. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199113.

Chattopadhyay B, Garg KM, Gwee CY, Edwards SV, Rheindt FE. Gene flow during glacial habitat shifts facilitates character displacement in a Neotropical flycatcher radiation. BMC Evol Biol. 2017;17:210.

Coyne J, Orr H. Speciation. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2004.

Coyne JA, Orr HA. Patterns of speciation in Drosophila revisited. Evolution. 1997;51:295–303.

Cruickshank TE, Hahn MW. Reanalysis suggests that genomic islands of speciation are due to reduced diversity, not reduced gene flow. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:3133–57.

Csilléry K, Blum MGB, Gaggiotti OE, François O. Approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) in practice. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:410–8.

Dasmahapatra KK, Walters JR, Briscoe AD, Davey JW, Whibley A, Nadeau NJ, Zimin AV, Hughes DST, Ferguson LC, Martin SH. Butterfly genome reveals promiscuous exchange of mimicry adaptations among species. Nature. 2012;487:94–8.

del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, Christie DA, de Juana E. Handbook of birds of the world. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions; 2018.

Delmore KE, Lugo Ramos JS, Van Doren BM, Lundberg M, Bensch S, Irwin DE, Liedvogel M. Comparative analysis examining patterns of genomic differentiation across multiple episodes of population divergence in birds. Evol Lett. 2018;2:76–87.

Dong F, Zou F-S, Lei F-M, Liang W, Li S-H, Yang X-J. Testing hypotheses of mitochondrial gene-tree paraphyly: unravelling mitochondrial capture of the Streak-breasted Scimitar Babbler (Pomatorhinus ruficollis) by the Taiwan Scimitar Babbler (Pomatorhinus musicus). Mol Ecol. 2014;23:5855–67.

Drake JM. Heterosis, the catapult effect and establishment success of a colonizing bird. Biol Lett. 2006;2:304–7.

Dreyer P, Gustavsson CG. Photographic documentation of a Swan Goose × Snow Goose Anser cygnoides × Anser caerulescens hybrid and its offspring with a Barnacle Goose (Branta leucopsis)—a unique three-species cross. Ornithol Anzeiger. 2009;49:41–52.

Durand EY, Patterson N, Reich D, Slatkin M. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2239–52.

Eaton DAR, Ree RH. Inferring phylogeny and introgression using RADseq data: an example from flowering plants (Pedicularis: Orobanchaceae). Syst Biol. 2013;62:689–706.

Edwards SV, Potter S, Schmitt CJ, Bragg JG, Moritz C. Reticulation, divergence, and the phylogeography–phylogenetics continuum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8025–32.

Elgvin TO, Trier CN, Tørresen OK, Hagen IJ, Lien S, Nederbragt AJ, Ravinet M, Jensen H, Sætre G-P. The genomic mosaicism of hybrid speciation. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1602996.

Enciso-Romero J, Pardo-Díaz C, Martin SH, Arias CF, Linares M, McMillan WO, Jiggins CD, Salazar C. Evolution of novel mimicry rings facilitated by adaptive introgression in tropical butterflies. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:5160–72.

Excoffier L, Foll M. fastsimcoal: a continuous-time coalescent simulator of genomic diversity under arbitrarily complex evolutionary scenarios. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1332–4.

Fowler A, Eadie J, Engilis A. Identification of endangered Hawaiian ducks (Anas wyvilliana), introduced North American mallards (A. platyrhynchos) and their hybrids using multilocus genotypes. Conserv Genet. 2009;10:1747.

Gante HF, Matschiner M, Malmstrøm M, Jakobsen KS, Jentoft S, Salzburger W. Genomics of speciation and introgression in Princess cichlid fishes from Lake Tanganyika. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:6143–61.

Grant P, Grant B. Hybridization of bird species. Science. 1992;256:193–7.

Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M, Patterson N, Li H, Zhai W, Fritz MHY, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710–22.

Grossen C, Seneviratne SS, Croll D, Irwin DE. Strong reproductive isolation and narrow genomic tracts of differentiation among three woodpecker species in secondary contact. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:4247–66.

Gutenkunst RN, Hernandez RD, Williamson SH, Bustamante CD. Inferring the joint demographic history of multiple populations from multidimensional SNP frequency data. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000695.

Harrison R. Hybrid zones and the evolutionary process. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Hedrick PW. Adaptive introgression in animals: examples and comparison to new mutation and standing variation as sources of adaptive variation. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:4606–18.

Hermansen J, Saether S, Elgvin T, Borge T, Hjelle E, Sætre G-P. Hybrid speciation in sparrows I: phenotypic intermediacy, genetic admixture and barriers to gene flow. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:3812–22.

Hey J. Isolation with migration models for more than two populations. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:905–20.

Hey J, Nielsen R. Multilocus methods for estimating population sizes, migration rates and divergence time, with applications to the divergence of Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis. Genetics. 2004;167:747–60.

Hobolth A, Christensen OF, Mailund T, Schierup MH. Genomic relationships and speciation times of human, chimpanzee, and gorilla inferred from a coalescent hidden Markov model. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e7.

Huerta-Sánchez E, Jin X, Bianba Z, Peter BM, Vinckenbosch N, Liang Y, Yi X, He M, Somel M, et al. Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature. 2014;512:194–7.

Huson DH. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73.

Irwin D, Rubtsov A, Panov E. Mitochondrial introgression and replacement between yellowhammers (Emberiza citrinella) and pine buntings (Emberiza leucocephalos) (Aves: Passeriformes). Biol J Linn Soc. 2009a;98:422–38.

Irwin DE, Brelsford A, Toews DPL, MacDonald C, Phinney M. Extensive hybridization in a contact zone between MacGillivray’s warblers Oporornis tolmiei and mourning warblers O. philadelphia detected using molecular and morphological analyses. J Avian Biol. 2009b;40:539–52.

Irwin DE, Milá B, Toews DPL, Brelsford A, Kenyon HL, Porter AN, Grossen C, Delmore KE, Alcaide M, Irwin JH. A comparison of genomic islands of differentiation across three young avian species pairs. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:4839–55.

Jacobsen F, Omland K. Extensive introgressive hybridization within the northern oriole group (Genus Icterus) revealed by three-species isolation with migration analysis. Ecol Evol. 2012;2:2413–29.

Jones MR, Mills LS, Alves PC, Callahan CM, Alves JM, Lafferty DJR, Jiggins FM, Jensen JD, Melo-Ferreira J, Good JM. Adaptive introgression underlies polymorphic seasonal camouflage in snowshoe hares. Science. 2018;360:1355–8.

Kim M, Cui M-L, Cubas P, Gillies A, Lee K, Chapman MA, Abbott RJ, Coen E. Regulatory genes control a key morphological and ecological trait transferred between species. Science. 2008;322:1116–9.

Kraus RHS, Wink M. Avian genomics: fledging into the wild! J Ornithol. 2015;156:851–65.

Krosby M, Rohwer S. A 2000 km genetic wake yields evidence for northern glacial refugia and hybrid zone movement in a pair of songbirds. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276:615–21.

Kulikova I, Zhuravlev Y, McCracken K. Asymmetric hybridization and sex-biased gene flow between Eastern Spot-billed Ducks (Anas zonorhyncha) and Mallards (A. platyrhynchos) in the Russian Far East. Auk. 2004;121:930–49.

Kutschera VE, Bidon T, Hailer F, Rodi JL, Fain SR, Janke A. Bears in a forest of gene trees: phylogenetic inference is complicated by incomplete lineage sorting and gene flow. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:2004–17.

Lamichhaney S, Berglund J, Almén MS, Maqbool K, Grabherr M, Martinez-Barrio A, Promerová M, Rubin C-J, Wang C, Zamani N, et al. Evolution of Darwin’s finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing. Nature. 2015;518:371–5.

Lavretsky P, Dacosta J, Hernandez-Banos B, Engilis A Jr, Sorenson MD, Peters J. Speciation genomics and a role for the Z chromosome in the early stages of divergence between Mexican ducks and mallards. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:5364–78.

Lawson DJ, van Dorp L, Falush D. A tutorial on how not to over-interpret STRUCTURE and ADMIXTURE bar plots. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3258.

Leppälä K, Nielsen SV, Mailund T. admixturegraph: an R package for admixture graph manipulation and fitting. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:1738–40.

Li H, Ralph P. Local PCA shows how the effect of population structure differs along the genome. Genetics. 2019;211:289–304.

Lijtmaer DA, Mahler B, Tubaro PL. Hybridization and postzygotic isolation patterns in pigeons and doves. Evolution. 2003;57:1411–8.

Lovette IJ, Bermingham E. Explosive speciation in the New World Dendroica warblers. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 1999;266:1629–36.

Mallet J, Besansky N, Hahn MW. How reticulated are species? BioEssays. 2016;38:140–9.

Mank JE, Carlson JE, Brittingham MC. A century of hybridization: decreasing genetic distance between American black ducks and mallards. Conserv Genet. 2004;5:395–403.

Martin NH, Bouck AC, Arnold ML. Detecting adaptive trait introgression between Iris fulva and I. brevicaulis in highly selective field conditions. Genetics. 2006;172:2481–9.

Martin SH, Van Belleghem SM. Exploring evolutionary relationships across the genome using topology weighting. Genetics. 2017;206:429–38.

Moore WS. An evaluation of narrow hybrid zones in vertebrates. Q Rev Biol. 1977;52:263–77.

Morales HE, Sunnucks P, Joseph L, Pavlova A. Perpendicular axes of differentiation generated by mitochondrial introgression. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:3241–55.

Nadachowska-Brzyska K, Burri R, Olason PI, Kawakami T, Smeds L, Ellegren H. Demographic divergence history of pied flycatcher and collared flycatcher inferred from whole-genome re-sequencing data. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003942.

Nater A, Burri R, Kawakami T, Smeds L, Ellegren H. Resolving evolutionary relationships in closely related species with whole-genome sequencing data. Syst Biol. 2015;64:1000–17.

Novembre J. Pritchard, stephens, and donnelly on population structure. Genetics. 2016;204:391–3.

Oswald JA, Overcast I, Mauck WM, Andersen MJ, Smith BT. Isolation with asymmetric gene flow during the nonsynchronous divergence of dry forest birds. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:1386–400.

Ottenburghs J. Exploring the hybrid speciation continuum in birds. Ecol Evol. 2018;8:13027–34.

Ottenburghs J, Kraus R, van Hooft P, van Wieren SE, Ydenberg RC, Prins HHT. Avian introgression in the genomic era. Avian Res. 2017a;8:30.

Ottenburghs J, Megens H-J, Kraus R, van Hooft P, van Wieren SE, Crooijmans RPMA, Ydenberg RC, Groenen MAM, Prins HHT. A history of hybrids? Genomic patterns of introgression in the True Geese. BMC Evol Biol. 2017b;17:201.

Ottenburghs J, van Hooft P, van Wieren S, Ydenberg RC, Prins HHT. Birds in a bush: toward an avian phylogenetic network. Auk. 2016;133:577–82.

Ottenburghs J, Ydenberg R, Van Hooft P, van Wieren S, Prins HHT. The Avian Hybrids Project: gathering the scientific literature on avian hybridization. Ibis. 2015;157:892–4.

Palkopoulou E, Lipson M, Mallick S, Nielsen S, Rohland N, Baleka S, Karpinski E, Ivancevic AM, To T-H, Daniel Kortschak R, et al. A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E2566–74.

Pardo-Diaz C, Salazar C, Baxter SW, Merot C, Figueiredo-Ready W, Joron M, Owen McMillan W, Jiggins CD. Adaptive introgression across species boundaries in heliconius butterflies. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002752.

Patterson N, Moorjani P, Luo Y, Mallick S, Rohland N, Zhan Y, Genschoreck T, Webster T, Reich D. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics. 2012;192:1065–93.

Payseur B. Using differential introgression in hybrid zones to identify genomic regions involved in speciation. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:806–20.

Pease JB, Hahn MW. Detection and polarization of introgression in a five-taxon phylogeny. Syst Biol. 2015;64:651–62.

Peters JL, Sonsthagen SA, Lavretsky P, Rezsutek M, Johnson WP, McCracken KG. Interspecific hybridization contributes to high genetic diversity and apparent effective population size in an endemic population of mottled ducks (Anas fulvigula maculosa). Conserv Genet. 2014;15:509–20.

Pickrell JK, Pritchard JK. Inference of population splits and mixtures from genome-wide allele frequency data. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002967.

Poelstra J, Vijay N, Bossu C, Lantz H, Ryll B, Müller I, Baglione V, Unneberg P, Wikelski M, Grabherr MG, Wolf JBW. The genomic landscape underlying phenotypic integrity in the face of gene flow in crows. Science. 2014;344:1410–4.

Pons JM, Sonsthagen S, Dove C, Crochet PA. Extensive mitochondrial introgression in North American Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) from the American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus) with little nuclear DNA impact. Heredity. 2014;112:226–39.

Poulsen H. Morphological and ethological notes on a hybrid between a domestic duck and a domestic goose. Behaviour. 1950;3:99–104.

Price T. Speciation in birds. Greenwood Village: Roberts and Company; 2008.

Price T, Bouvier M. The evolution of F1 postzygotic incompatbilities in birds. Evolution. 2002;56:2083–9.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Proulx SR, Promislow DEL, Phillips PC. Network thinking in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:345–53.

Racimo F, Sankararaman S, Nielsen R, Huerta-Sánchez E. Evidence for archaic adaptive introgression in humans. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:359–71.

Randler C. Hybrid wildfowl in central Europe—an overview. Waterbirds. 2008;31:143–6.

Rapos do Amaral F, Coelho MM, Aleixo A, Luna LW, Rêgo PS, Araripe J, do Souza TO, Silva WAG, Thom G. Recent chapters of Neotropical history overlooked in phylogeography: shallow divergence explains phenotype and genotype uncoupling in Antilophia manakins. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:4108–20.

Reifová R, Majerová V, Reif J, Ahola M, Lindholm A, Procházka P. Patterns of gene flow and selection across multiple species of Acrocephalus warblers: footprints of parallel selection on the Z chromosome. BMC Evol Biol. 2016;16:130.

Rheindt FE, Edwards SV. Genetic introgression: an integral but neglected component of speciation in birds. Auk. 2011;128:620–32.

Rodríguez-Gómez F, Ornelas JF. Genetic structuring and secondary contact in the white-chested Amazilia hummingbird species complex. J Avian Biol. 2018;49:jav-01536.

Roman I, Bourgeois Y, Reyes-Velasco J, Jensen OP, Waldman J, Boissinot S. Contrasted patterns of divergence and gene flow among five fish species in a Mongolian rift lake following glaciation. Biol J Linn Soc. 2018;125:115–25.

Runemark A, Trier CN, Eroukhmanoff F, Hermansen JS, Matschiner M, Ravinet M, Elgvin TO, Sætre G-P. Variation and constraints in hybrid genome formation. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2:549–56.

Schraiber JG, Akey JM. Methods and models for unravelling human evolutionary history. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:727–40.

Schrider DR, Ayroles J, Matute DR, Kern AD. Supervised machine learning reveals introgressed loci in the genomes of Drosophila simulans and D. sechellia. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007341.

Schrider DR, Kern AD. Supervised machine learning for population genetics: a new paradigm. Trends Genet. 2018;34:301–12.

Schweizer M, Warmuth V, Alaei Kakhki N, Aliabadian M, Förschler M, Shirihai H, Suh A, Burri R. Parallel plumage color evolution and introgressive hybridization in wheatears. J Evol Biol. 2019;32:100–10.

Seehausen O, Butlin RK, Keller I, Wagner CE, Boughman JW, Hohenlohe PA, Peichel CL, Saetre G-P, Bank C, Brännström Å, et al. Genomics and the origin of species. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:176–92.

Shipham A, Schmidt DJ, Joseph L, Hughes JM. A genomic approach reinforces a hypothesis of mitochondrial capture in eastern Australian rosellas. Auk. 2017;134:181–92.

Solís-Lemus C, Bastide P, Ané C. PhyloNetworks: a package for phylogenetic networks. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3292–8.

Song Y, Endepols S, Klemann N, Richter D, Matuschka F-R, Shih C-H, Nachman MW, Kohn MH. Adaptive introgression of anticoagulant rodent poison resistance by hybridization between Old World mice. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1296–301.

Sonsthagen SA, Wilson RE, Chesser RT, Pons J-M, Crochet P-A, Driskell A, Dove C. Recurrent hybridization and recent origin obscure phylogenetic relationships within the ‘white-headed’ gull (Larus sp.) complex. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;103:41–54.

Suarez-Gonzalez A, Lexer C, Cronk QCB. Adaptive introgression: a plant perspective. Biol Lett. 2018;14:20170688.

Sun Y, Abbott RJ, Lu Z, Mao K, Zhang L, Wang X, Ru D, Liu J. Reticulate evolution within a spruce (Picea) species complex revealed by population genomic analysis. Evolution. 2018;72:2669–81.

Taysom A, Johnson J, Guay PJ. Establishing a genetic system to distinguish between domestic Mallards, Pacific Black Ducks and their hybrids. Conserv Genet Resour. 2014;6:197–9.

Thies L, Tomkovich P, dos Remedios N, Lislevand T, Pinchuk P, Wallander J, Dänhardt J, Þórisson B, Blomqvist D, Küpper C. Population and subspecies differentiation in a high latitude breeding wader, the Common Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula. Ardea. 2018;106:163–76.

Thom G, Do Amaral FR, Hickerson MJ, Aleixo A, Araujo-Silva LE, Ribas CC, Choueri E, Miyaki CY. Phenotypic and genetic structure support gene flow generating gene tree discordances in an Amazonian floodplain endemic species. Syst Biol. 2018;67:700–18.

Toews D, Brelsford A. The biogeography of mitochondrial and nuclear discordance in animals. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:3907–30.

Toews DPL, Mandic M, Richards JG, Irwin DE. Migration, mitochondria, and the yellow-rumped warbler. Evolution. 2014;68:241–55.

Toews DPL, Streby HM, Burket L, Taylor SA. A wood-warbler produced through both interspecific and intergeneric hybridization. Biol Lett. 2018;14:20180557.

Toews DPL, Taylor SA, Vallender R, Brelsford A, Butcher BG, Messer PW, Lovette IJ. Plumage genes and little else distinguish the genomes of hybridizing warblers. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2313–8.

Vallender R, Robertson R, Friesen V, Lovette I. Complex hybridization dynamics between golden-winged and blue-winged warblers (Vermivora chrysoptera and Vermivora pinus) revealed by AFLP, microsatellite, intron and mtDNA markers. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:2017–29.

Vijay N, Bossu CM, Poelstra JW, Weissensteiner MH, Suh A, Kryukov AP, Wolf JBW. Evolution of heterogeneous genome differentiation across multiple contact zones in a crow species complex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13195.

Walsh J, Kovach AI, Olsen BJ, Gregory Shriver W, Lovette IJ. Bidirectional adaptive introgression between two ecologically divergent sparrow species. Evolution. 2018;72:2076–89.

Wang W, Wang Y, Lei F, Liu Y, Wang H, Chen J. Incomplete lineage sorting and introgression in the diversification of Chinese spot-billed ducks and mallards. Curr Zool. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/cz/zoy074.

Wen D, Nakhleh L. Coestimating reticulate phylogenies and gene trees from multilocus sequence data. Syst Biol. 2017;67:439–57.

Wen D, Yu Y, Zhu J, Nakhleh L. Inferring phylogenetic networks using PhyloNet. Syst Biol. 2018;67:735–40.

Whitney KD, Broman KW, Kane NC, Hovick SM, Randell RA, Rieseberg LH. Quantitative trait locus mapping identifies candidate alleles involved in adaptive introgression and range expansion in a wild sunflower. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:2194–211.

Whitney KD, Randell RA, Rieseberg LH. Adaptive introgression of abiotic tolerance traits in the sunflower Helianthus annuus. New Phytol. 2010;187:230–9.

Whitney KD, Randell RA, Rieseberg LH. Adaptive introgression of herbivore resistance traits in the weedy sunflower Helianthus annuus. Am Nat. 2006;167:794–807.

Willis PM, Symula RE, Lovette IJ. Ecology, song similarity and phylogeny predict natural hybridization in an avian family. Evol Ecol. 2014;28:299–322.

Wolf JBW, Ellegren H. Making sense of genomic islands of differentiation in light of speciation. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:87–100.

Wu C-I. The genic view of the process of speciation. J Evol Biol. 2001;14:851–65.

Wu D-D, Ding X-D, Wang S, Wójcik JM, Zhang Y, Tokarska M, Li Y, Wang M-S, Faruque O, Nielsen R, Zhang Q, Zhang Y-P. Pervasive introgression facilitated domestication and adaptation in the Bos species complex. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0562-y.

Yu Y, Barnett RM, Nakhleh L. Parsimonious inference of hybridization in the presence of incomplete lineage sorting. Syst Biol. 2013;62:738–51.

Zhang C, Ogilvie HA, Drummond AJ, Stadler T. Bayesian inference of species networks from multilocus sequence data. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:504–17.

Zhang D, Song G, Gao B, Cheng Y, Qu Y, Wu S, Shao S, Wu Y, Alström P, Lei F. Genomic differentiation and patterns of gene flow between two long-tailed tit species (Aegithalos). Mol Ecol. 2017;26:6654–65.

Zhu J, Wen D, Yu Y, Meudt HM, Nakhleh L. Bayesian inference of phylogenetic networks from bi-allelic genetic markers. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14:e1005932.

Acknowledgements

The ideas in this paper are based on the final chapter of my Ph.D. thesis. I am grateful to my supervisors—Herbert Prins, Ron Ydenberg, Pim van Hooft, Sip van Wieren, Hendrik-Jan Megens and Martien Groenen—for letting me explore and develop these concepts. I also thank Per Alström and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions which improved this manuscript. And I thank Lynx Edicions for permission to publish illustrations.

Funding

This study was funded by Stichting de Eik.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JO conceived the idea, conducted the literature search and wrote the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

JO obtained his Ph.D. at Wageningen University (The Netherlands) where he studied the genomic consequences of hybridization between different goose species. He is currently exploring this system in greater detail as a postdoc at Uppsala University (Sweden). JO runs the Avian Hybrids Project (https://avianhybrids.wordpress.com/), a website gathering the scientific literature on hybridization in birds.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interest.

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Overview of patterns of hybridization in six bird orders (Anseriformes, Galliformes, Charadriiformes, Piciformes, Apodiformes and Passeriformes), based on the Serge Dumont Bird Hybrid Database (http://www.bird-hybrids.com).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ottenburghs, J. Multispecies hybridization in birds. Avian Res 10, 20 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-019-0159-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-019-0159-4