Abstract

Freeze-thaw cycles can cause considerable damage to porous materials and thus have an adverse effect on the durability of mortars and porous stone. To assess the behavior and frost resistance of two types of porous limestone, three commercially available repair mortars and four mixtures of laboratory-prepared repair mortars were subjected to freeze-thaw cycles according to EN 12371. During the test, samples of stone and mortar were bonded together and the weight loss was continuously monitored. The adhesion bond between the stone and the mortar was also observed during the cycles. Petrographic analysis and thin sections were also made before and after the freeze-thaw test. The pore size distribution (mercury intrusion porosimetry, MIP) of mortars and stones was also measured. The test showed that most of the repair mortars were damage more than porous limestone due to frost action. Two exceptions are two commercial available repair mortars. These mortars were able to keep the adhesion with the stone, and the frost did not modify significantly the cubic shape of the test specimens, only rounding of the edges was observed. All other samples were broken during the frost tests; stone/mortar interface was dismounted. Other typical damage features such as delamination, blistering, powdering, and granular disintegration were also observed leading to the gradual surface loss of the material. Our tests proved that low pozzolanic cement content in mortars decreases the material durability. According to the pore size distribution (MIP), the small pores (around 0.1 μm) control the weathering behavior of tested porous materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phase transition of water to ice causes severe damage to stones, causing frost damage which has been already described many years ago (Schaffer 1932). The weathering mechanism of porous materials is almost the same in the case of frost and salt crystallization. Some of the salt tests could cause higher structural stress on the stone matrix than frost damage—what suggests, that weathering process is faster in a salt-rich environment (Cárdenes et al. 2013). Stone and mortar damage depends on relative humidity (RH), temperature, and pore structure in salt-rich environment (Linnow 2007), while in region, the damage is mainly controlled by the presence of the water, the porosity, the pore size distribution, and the saturation rate (Ruedrich et al. 2011, Al-Omari et al. 2015, Gökçe et al. 2016). Frost damage can lead to material loss, and in addition, it also decreases the stone durability against other stress factors such as salts (Yu and Oguchi 2010). Earlier test results showed that carbonate stones have higher resistance against frost than salt crystallization (Thomachot-Schneider et al. 2010, 2011, Cárdenes et al. 2013). It has been also outlined that pore sizes play an important role in frost resistivity of stones, namely, pore throat sizes control the resistance of rock against weathering (Benavente et al. 2007, 2011 Martínez-Martínez et al. 2013). The sensitivity to salt weathering was linked to pore sizes. Various authors denoted various pore ranges that make the stone/mortar prone to salt weathering (Age and Oguchi 2011). Yu and Oguchi (2010) emphasized that pores of 0.1 μm in diameter are damaged the most during salt crystallization, similarly to Ordonez (1997), while Steiger (2005a, 2005b) showed that materials characterized by smaller pores of 0.05 μm are also sensitive to salt weathering. Larger pore size (1 μm) was found to be responsible for salt damage of porous stones (Benavente et al. 2004). The pore size also controls the durability of mortars (Papayianni and Stefanidou 2006, Grilo et al. 2014, Korat et al. 2015, Giosuè et al. 2018). Thus, natural stone and mortar durability are closely related (Klisińska-Kopacz et al. 2010, Rivas et al. 2010, Yu and Oguchi 2010, Schueremans et al. 2011, Szemerey-Kiss and Török 2011a, 2012, 2017a; Szemerey-Kiss et al. 2013, Isebaert et al. 2014). The strength of mortars against crystallization pressure is also controlled by microfabric, mineralogical composition, and pore structure (Arizzi and Cultrone 2012, Szemerey-Kiss and Török 2011b, Pavia and Hanley 2010, Lanas et al. 2006). In terms of aggregate and binder composition, the durability of mortars is very different (Isebaert et al. 2014). Hydrated lime additions to the cement-based mortars improve the workability, the bond strength, and some cases the durability (Duran et al. 2014). On the other hand, according to Lanas et al. (2006), mortars with high porosity and low strength are more susceptible to degradation due to freeze-thaw cycles. The susceptibility of lime mortars to frost damage is well known, especially of young non-carbonated mortars.

The present paper compares the frost durability of porous limestone and mortars. It is a key question when repair mortars are applied in heritage structures (Isebaert et al. 2014). The aim is to assess the compatibility of three commercial available repair mortars and four mixture of laboratory-prepared repair mortars with porous limestone under harsh environmental conditions. The tested mortars are suggested to be used to repair porous stone. During the tests, not only the individual behavior of mortars and porous limestone is tested but also the strength of the bond between limestone substrate and mortar is also evaluated. The bond between mortar and stone and the compatibility of physical properties are also important issues that control the long-term behavior of loss compensation (Griswold and Uricheck 1998, Van Balen et al. 2005). The compatibility is also assessed in terms of changes in microfabric and weight loss of specimens. In addition, the pore size distribution of test specimens was also assessed to link the porosity to the frost resistance of mortars and porous limestone.

Methods/Experimental

Sample preparation

The stones and the used aggregates were collected from Sóskút quarry. It is located 38 km to the southwest of the city Budapest. Two main types of porous limestone were used for tests: (i) a fine-grained oolitic limestone (FL) and (II) a coarse-grained bioclastic oolitic limestone (CL). The detailed description of limestone types is given by Török (2003) and Pápay and Török (2015, 2018). Mortar specimens were also tested. Ten types of mixtures were prepared. Two mixtures were made using portland cement and various proportion of hydrated lime, limestone sand, and quartz sand (types A and B) (Table 1).

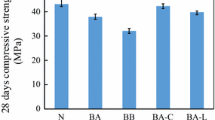

Two additional mixtures were prepared adding portland pozzolanic cement (types C and D). The materials that were used for types A–D were hydraulic lime with density of 2.24 g/cm3 and portland pozzolanic cement with material density of 3.14 g/cm3 and fine limestone aggregate of 1–2 mm or less in size with material density of 2.69 g/cm3 or quartz sand with a material density of 2.65 g/cm3. Three additional ready-to-mix mortars were also tested marked as T, R, and K. Their composition is also given in Table 1. Additionally, samples with 50 m% of limestone sand aggregate were also prepared. Thus, in these types of specimens, sand-sized porous limestone was used as aggregate (Table 1). These mixtures are marked with T50, R50, and K50 throughout the paper. Two types of samples were prepared from mortars. First sets were cubes of mortars of 30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm in size which were made in stainless steel casts. The second sets are prismatic specimens of 40 mm × 40 mm × 80 mm, where one half of the specimen is porous limestone and the other half is mortar, a composite sample (Fig. 1). Both fine- and coarse-grained limestone samples (FL, CL) were used for these test specimens (Fig. 2). The textural properties of these limestone types have been described in previous works (Török 2003, Pápay and Török 2010, Szemerey-Kiss and Török 2012). These limestone/mortar samples were also prepared in stainless steel casts. During the curing, the stone/mortar interface was kept in contact to provide an excellent binding. Both types of samples (pure mortars and stone/mortar composites) were kept in the cast for 24 h prior to removing from the steel frames. Once demolded, the specimens were cured for 28 days at room temperature (20 °C ± 5 °C) under controlled RH. All together, 48 samples were prepared: 30 cubes of 30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm and 18 prismatic specimens of 40 mm × 40 mm × 80 mm.

Samples of repair mortars/limestone prisms (dashed lines represent the boundaries). a Coarse-grained limestone and repair mortar R. b Coarse-grained limestone and repair mortar T50. c Fine-grained limestone and repair mortar T. d Fine-grained limestone and repair mortar T50 (explanation for sample codes are given in Table 1)

Mercury intrusion porosimetry and apparent porosity

The measurements were made with a Carlo Erba 2000 (GFZ Potsdam) porosimeter. The collected data evaluation was made by Pascal software (version 1.03). Cylindrical specimens of 10 mm in diameter and different length samples were drilled from mortars and from stone samples for the pore size distribution analyses. Before the tests, samples were dried in an oven to constant mass at 105 °C. The apparent porosity of test specimens was also determined according to EN 1936:2007.

Freeze-thaw test

For the freeze-thaw test, the European Norm Standard used as a reference was EN 12371 natural stone methods-determination of frost resistance. The samples were initially dried and then submerged in distilled water at 20 °C until full saturation. After this time, the samples were placed in a freeze chamber at − 20 to − 22 °C for 6 h. After freezing, the samples were removed and kept in water for 6 h. These two steps comprised one cycle. Weight of the specimens was measured before and after each freeze cycle. Test specimens of mortars were subjected to 25 freeze-thaw cycles.

Polarizing microscopy analyses

Thin sections were prepared from test specimens prior and after the freeze-thaw cycles to detect microfabric changes. Epoxy resin was used to impregnate the porous specimens, and slices were cut after impregnation. The microfabric analysis of thin sections was performed by using polarizing microscopy (ZEISS Axio Imager A2m microscope).

Results

Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) porosity measurements indicate that there are major differences in between the pore size distribution of limestone samples and mortars (Fig. 3). Larger pores (larger than 10 μm) prevail in limestones (more than 55%) while the pores of the mortars are in the lower size ranges (Table 2). In the mortar samples, the prevailing pore ranges are in between 0.1 and 1 μm with the exception of T, R, and R50 mortars. In the former one, 0.01–0.1 pores are the most common, while in the latter ones, (R, R50) larger pores (1–10 μm) predominate. The apparent porosity of mortars is less than 30%, with the exceptions of T50, R50, K, and K50 mortars (Table 2).

Pore size distribution of the tested specimens. FL and CL are porous limestone and A, B, C, D, T, T50, R, R50, K, and KR50 are repair mortars, detailed descriptions of samples are given in the text and in Table 1)

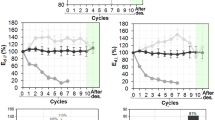

The freeze-thaw tests showed that most of the limestone samples are hardly affected even after 25 frost cycles. Damages are observed in the form of minor rounding of edges. Tested commercial mortars of T and R have higher frost resistance than any of the tested limestone samples. Damage of mortar samples is seen after 10 freeze-thaw cycles, but major damage is observed at several samples after 25 freeze-thaw cycles (Fig. 4).

The visible signs of frost damage appeared in the forms of surface spalling or microcrack formation (Fig. 5).

The weight loss of laboratory-prepared mortar samples related to frost action is different. D mortar with no added lime has the highest frost resistance, while hydrated lime-containing samples (sample set A and B) have the lowest frost durability (Fig. 6).

Average weight loss (%) of the tested specimens (A, B, C, and D, see sample description in Table 1) (please note that there is an overlap between the symbols up to 10 cycles)

The commercially available mortars seemed to be relatively frost resistant, but the K mortar showed a weight loss of nearly 20% after 25 freeze-thaw cycles (Fig. 7). When limestone aggregate was added, the frost resistance of these mortars was reduced in different rates (Fig. 7.). The lowest durability was found at K50 mortar, which completely disintegrated after 25 freeze-thaw cycles. The damage of pure cement and hydrated lime-based mortars (T and R) during freeze-thaw cycling was lower.

Average weight loss (%) of mortar samples (T, T50, R, R50, K, and K50, see legend in Table 1 and in the text) (please note that there is an overlap between the symbols at 0.00 line up to 21 cycles)

Microscopic analyses of limestone samples suggest that frost action causes the formation of microcracks and these cracks tend to open (Fig. 8). The cracks were found in the porous Hungarian limestone in the carbonate cement between the grains and also within the carbonate grains. Larger cracks (80–100 μm) and networks of smaller intragranular microcracks were also visualized by using a microscope (Fig. 8).

Cracks developed within the porous limestone due to frost damage. Microscopic images (crossed polars): a fine-grained oolitic limestone (FL) with microcracks in between the grain boundaries crossing microsparitic cement and b opened microcrack at grain boundary coarse-grained oolitic limestone (CL) (arrows show microcracks)

Mortar specimens have slightly different microcrack patterns according to microscopic images. Many cracks are formed parallel to the surface of the mortar (Fig. 9).

Surface parallel cracks (arrows) observed in mortar specimens. a Mortar A. b Mortar C (see sample description in Table 1). The boundaries of split surfaces are marked by red lines

Damage and disintegration of bonds between mortar and limestone during freeze-thaw cycling were not gradual. Comparing the results of the failure of the tested mortar/stone composite samples, it is evident that visible cracks are not necessarily formed prior to the separation of stone/mortar interface (Table 3). There were composite specimens that showed the formation of microcracks prior to the dismounting (e.g., C and D, Table 3), but there were mortars where the bounds between the stone and mortar were eliminated without any sign of crack formation (e.g., K50, Table 3). The most common failure was the forms of cracks at the stone/mortar interface (Fig. 10).

Discussion

Previous studies suggest that the porosity and pore size distribution have an important role in the durability of construction materials under laboratory conditions (Benavente et al. 2004; Chen and Wu 2013; Chen et al. 2013; Martínez-Martínez et al. 2013; Al-Omari et al. 2015; Pápay and Török 2018) and also in exposed buildings (Thomachot-Schneider et al. 2011, Vázquez et al. 2015, Gökçe et al. 2016). In this study, the most durable mortars were the ones of D, T, and R (Figs. 6 and 7). These mortars have very different pore size distributions (Table 2 and Fig. 3). D and T mortars have a very high amount of pores in the pore ranges of 0.01–0.1 μm (Table 2). This pore range was considered as one of the most sensitive ones in terms of salt damage (Yu and Oguchi 2010), while Benavente et al. (2004) suggested that larger pores (0.1–10 μm) all contribute to salt damage. Other authors (Steiger 2005a, 2005b; Cárdenes et al. 2013) clearly noted that smaller pores can be also considered in salt damage. Frost damage is also linked to porosity, and there is a strong link between humidity, capillary condensation, and frost damage of porous materials (Al-Omari et al. 2015; Scrivano et al. 2018). Besides porosity and pore size distribution, the composition also controls the frost resistance of the tested mortars. Mortars that contain pozzolanic cement with hydrated lime are more sensitive to frost action (K, Table 1, Fig. 7) than the ones that contain portland cement (T and R, Table 1, Fig. 7). It was also documented for pozzolanic mortars that the frost damage is clearly related to microcrack formation (Siline et al. 2017). At the tested mortars, microcracking and spalling occurred, and granular disintegration was also observed (Fig. 5) after 10 to 15 cycles. Granular disintegration was also reported even after 5 freeze-thaw cycles when lime mortars were tested (Nunes and Slízková 2016). The fact that granular disintegration was only observed after 10 cycles and not earlier could be related to the presence of portland cement in all tested specimens.

The freeze-thaw cycles cause somewhat similar damage forms on mortars and artificial stones to the ones related to salt damage (Rusin and Swiercz 2017, Husillos-Rodriguez et al. 2018). The latter one is also characterized by microcracking, granular disintegration, and scaling (Thomachot-Schneider et al. 2016). Similarly, the frost damage in limestone also appears in the form of crack formation under laboratory conditions (Martínez-Martínez et al. 2013) and also in monuments (Török 2003, Laycock et al. 2008), while it was observed here under the microscope (Fig. 8).

Similar cracks were observed by Martínez-Martínez et al. (2013) studying six limestone types under simulated frost weathering. Our observations are also in good agreement with the findings of Al-Omari et al. (2015), since in that paper, the damage of highly porous French limestone due to frost action was recorded as microcrack formation.

Earlier tests have shown that the rate of the frost damage in Miocene limestone depends on the different texture of this limestone type (Pápay and Török 2018). There are fine-grained, medium-grained, and coarse limestone types of porous limestone extracted the same quarry—Sóskút (Török 2003, Török et al. 2004), and these limestones have a different pore size distribution that affects their durability and resistance to weathering (Török and Rozgonyi 2004). According to Szemerey-Kiss and Török (2011b) and Pápay and Török (2018), most of the Miocene limestone is not frost resistant. The highly porous limestone of Central France is similar to the studied ones since its frost resistance is also limited and controlled by porosity (Hassine et al. 2018a) and relative humidity (Al-Omari et al. 2015). The water infiltration can also cause strain (Hassine et al. 2018b), but the strain is much enhanced by frost action (Al-Omari et al. 2015) that can lead to the formation of microcracks and damage of the limestone (Martínez-Martínez et al. 2013).

Garbalinska and Wygocka (2014) showed that these cracks are related to the internal structure of the cement mortars and pore size distribution, too. In this study, the relationships between crack formation and pore size distribution cannot be clearly outlined. However, damage patterns can be linked to porosity; namely, the mortar that was the least durable (T50, Fig. 7) has the highest amount of pores in the pore range of 0.1–1 μm (Table 2).

The previous test has demonstrated that various failure modes exist between mortar and limestone (Szemerey-Kiss and Török 2017a). The surface adherence of mortar also depends on the surface pretreatment (wetting, etc.), and it has been demonstrated that the adherence strength of mortar to limestone is much lower (Szemerey-Kiss and Török 2017a) than that of the concrete (Sadowski and Hola 2015; Sadowski et al. 2016). The surface adherence also depends on surface roughness (Sadowski and Mathia 2016), and it seems that adding limestone sand to mortar increases surface roughness and probably contributes to the increase of frost resistance of mortar/limestone interface (Table 2). The appearance of cracks does not necessarily predict the failure at stone/mortar interface since there are several specimens (A2, B1, R2, and R501 in Table 3) where no cracks were observed prior to failure (separation of stone/mortar interface). The adherence of the mortar to the stone surface is also controlled by the durability of the mortar itself; mortars with low frost durability (e.g., D (Fig. 6) or K50 (Fig. 7)) were separated from the stone surface after a lower number of freeze-thaw cycles (Table 3).

These tests also provide information on how many freeze-thaw cycles are needed to assess the durability of these mortars (Szemerey-Kiss and Török 2017b). Goudie (1999) used 80 cycles in his study to guarantee that at least two thirds of the samples were affected by the freeze-thaw. In our study, 25 cycles were reached and these provided a good hint to observe the differences in durability; however, some authors emphasize the use of an even higher number of freeze-thaw cycles to better understand the frost durability of natural stones (Martínez-Martínez et al. 2013) and mortars (Siline et al. 2017).

Conclusions

The freeze-thaw test of repair mortars and porous limestone indicates that there is a strong link between porosity and frost durability. Adding limestone aggregate to ready-to-mix mortars reduces the frost durability. The mortars that contain pozzolanic cement are more sensitive to frost than the ones of portland cement binders. Adding hydraulic lime accelerates curing, but often reduces the frost durability of mortars. Frost damage of limestone/mortar interface appears in the form of microcracks and dismounting of the mortar from the stone. Microcrack formation does not necessarily occur prior to losing the adhesion of the stone surface. It could happen rapidly without visible signs.

References

Al-Omari A, Beck K, Brunetaud X, Török Á, Al-Mukhtar M (2015) Critical degree of saturation: a control factor of freeze-thaw damage of porous limestones at Castle of Chambord, France. Eng Geol 185:71–80

Arizzi A, Cultrone G (2012) The difference in behaviour between calcitic and dolomitic lime mortars set under dry conditions: the relationship between textural and physical-mechanical properties. Cem Concr Res 42:818–826

Aye T, Oguchi CT (2011) Resistance of plain and blended cement mortars exposed to severe sulfate attacks. Constr Build Mater 25:2988–2996

Benavente D, Cueto N, Martínez-Martínez J, Garcìa Del Cura MA, Cañaveras JC (2007) The influence of petrophysical properties on the salt weathering of porous building rocks. Environ Geol 52:215–224

Benavente D, Garcia del Cura MA, Fort R, Ordónez S (2004) Durability estimation of porous building stones from pore structure and strength. Eng Geol 74:113–127

Benavente D, Sanchez-Moral S, Fernandez-Cortes A, Cañaveras JC, Elez J, Sáiz-Jiménez C (2011) Salt damage and microclimate in the Postumius Tomb, Roman necropolis of Carmona, Spain. Environ Geol 63:1529–1543

Cárdenes V, Maetos FJ, Fernándet-Lorenzo S (2013) Analysis of the correlations between freeze-thaw and salt crystallization tests. Environ Earth Sci 71:1123–1134

Chen X, Wu S (2013) Influence of water-to-cement ratio and curing period on pore structure of cement mortar. Constr Build Mater 38:804–812

Chen X, Wu S, Zhou J (2013) Influence of porosity on compressive and tensile strength of cement mortar. Constr Build Mater 40:869–874

Duran A, Navarro-Blasco I, Fernández JM, Alvarez JI (2014) Long-term mechanical resistance and durability of air lime mortars with large additions of nanosilica. Constr Build Mater 58:147–158

Garbalinska H, Wygocka A (2014) Microstructure modification of cement mortars: effect on capillarity and frost-resistance. Constr Build Mater 51:258–266

Giosuè C, Yu QL, Ruello ML, Tittarelli F, Brouwers HJH (2018) Effect of pore structure on the performance of photocatalytic lightweight lime-based finishing mortar. Constr Build Mater 171:232–242

Gökçe MV, Ince I, Fener M, Taşkıran T, Kayabali K (2016) The effects of freez-thaw (F-T) cycles on the Gödene travertine used in historical structures in Konya (Turkey). Cold Reg Sci Technol 127:65–75

Goudie A (1999) A Comparison of the Relative Resistance of Limestones to Frost and Salt Weathering. Permafrost Periglac Process 10:309–316

Grilo J, Faria P, Veiga R, Silva AS, Silva V, Velosa A (2014) New natural hydraulic lime mortars – physical and microstructural properties in different curing conditions. Constr Build Mater 54:378–384

Griswold J, Uricheck S (1998) Loss compensation methods for stone. J Am Inst Conserv 37:89–110

Hassine MA, Beck K, Brunetaud X, Al-Mukhtar M (2018a) Use of electrical resistance measurement to assess the water saturation profile in porous limestones during capillary imbibition. Constr Build Mater 165:206–217

Hassine MA, Beck K, Brunetaud X, Al-Mukhtar M (2018b) Strain measurements during capillary water infiltration in porous limestones. Constr Build Mater 165:439–447

Husillos-Rodríguez N, Carmona-Quiroga PM, Martínez-Ramírez S, Blanco-Varela MT, Fort R (2018) Sacrificial mortars for surface desalination. Constr Build Mater 173:452–460

Isebaert A, Van Parys L, Cnudde V (2014) Composition and compatibility requirements of mineral repair mortars for stone – a review. Constr Build Mater 59:39–50

Klisińska-Kopacz A, Tišlova R, Adamski G, Kozłowski R (2010) Pore structure of historic and repair Roman cement mortars to establish their compatibility. J Cult Herit 11:404–410

Korat L, Mirti B, Mladenovi A, Pranji AM, Kramar S (2015) Formulation and microstructural evaluation of tuff repair mortar. J Cult Herit 16:705–711

Lanas J, Sirera R, Alvarez JI (2006) Study of the mechanical behaviour of masonry lime-based mortars cured and exposed under different conditions. Cem Concr Res 36:961–970

Laycock EA, Spence K, Jefferson DP, Hetherington S, Martin B, Wood C (2008) Testing the durability of limestone for chatedral façade restoration. Environ Geol 56:521–528

Linnow K (2007) Salt damage in porous materials: an RH-XRD investigation, PhD dissertaton. Dissertation Zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades vorgelegt im Department Chemie der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften Universität, Hamburg, p 167

Martínez-Martínez J, Benavente D, Gomez-Heras M, Marco-Castańo L, García-del-Cura M (2013) Non-linear decay of building stones during freeze–thaw weathering processes. Constr Build Mater 38:443–454

Nunes C, Slízková Z (2016) Freezing and thawing resistance of aerial lime mortar with metakaolin and a traditional water-repellent admixture. Constr Build Mater 114:896–905

Ordonez S, Fort R, García del Cura MA (1997) Pore size distribution and the durability of a porous limestone. Q J Eng Geol 30:221–230

Pápay Z, Török Á (2010) Physical changes of porous Hungarian limestones related to silicic acid ester consolidant treatments. Geol Soc Lond, Spec Publ 331:147–155

Pápay Z, Török Á (2015) Micro-Fabric, Pore-Size Distribution and Water Absorption of Consolidated Porous Limestone. In: Lollino G, Giordan D, Marunteanu C, Christaras B, Yoshinori I, Margottini C (eds) Engineering Geology for Society and Territory - Volume 8: Preservation of Cultural Heritage. 12th IAEG Congress. Springer Switzerland, Torino, pp 553–556

Pápay Z, Török Á (2018) Effect of thermal and freeze-thaw stress on the mechanical properties of porous limestone. Period Polytech Civ Eng 62:423–428

Papayianni I, Stefanidou M (2006) Strength–porosity relationships in lime–pozzolan mortars. Constr Build Mater 20:700–705

Pavia S, Hanley R (2010) Flexural bond strength of natural hydraulic lime mortar and clay brick. Mater Struct 43:913–922

Rivas T, Alvarez E, Mosquera MJ, Aljeano L, Taboada J (2010) Crystallization modifiers applied in granite desalination: the role of the stone pore structure. Constr Build Mater 24:766–776

Ruedrich J, Kirchner D, Siegesmund S (2011) Physical weathering of building stones induced by freeze–thaw action: a laboratory long-term study. Environ Earth Sci 63:1573–1586

Rusin Z, Swiercz P (2017) Frost resistance of rock materials. Constr Build Mater 148:704–714

Sadowski L, Czarnecki S, Hola J (2016) Evoluation of the height 3D roughness parameters of concrete substrate and adhesion to epoxy resin. Int J Adhes Adhes 67:3–13

Sadowski L, Hola J (2015) ANN modelling of pull-off adhesion of concrete layers. Adv Eng Softw 89:17–27

Sadowski L, Mathia TG (2016) Multi-scale metrology of concrete surface morphology: fundamentals and specificity. Constr Build Mater 113:613–621

Schaffer RJ (1932) The weathering of natural building stones. His Majesty’s Stationary Office, London, p 149

Schueremans L, Cizer Ö, Janssens E, Serré G, Van Balen K (2011) Characterization of repair mortars for the assessment of their compatibility in restoration projects: research and practice. Constr Build Mater 25:4338–4350

Scrivano S, Gaggero L, Aguilar J (2018) Micro-porosity and micro-petrographic features influences on decay: experimental data from four dimension stones. Constr Build Mater 173:342–349

Siline M, Elhem G, Mekki B (2017) Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on the physicomechanical properties of a pozzolanic mortar. Constr Build Mater 134:32–38

Steiger M (2005a) Crystal growth in porous materials – I. the crystallization pressure of large crystals. J Cryst Growth 282:455–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2005.05.00

Steiger M (2005b) Crystal growth in porous materials – II. influence of crystal size on the crystallization pressure. J Cryst Growth 282:470–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2005.05.008

Szemerey-Kiss B, Török Á (2011a) Time-dependent changes in the strength of repair mortar used in loss compensation of stone. Environ Earth Sci 63:1613–1621

Szemerey-Kiss B, Török Á (2011b) Salt durability tests of repair mortars used in the restoration of porous limestones. In: Ioannou I, Theodoridou M (eds) Salt Weathering on Buildings and Stone Sculptures, SWBSS, Limassol, pp 323–330

Szemerey-Kiss B, Török Á (2012) Porosity and compatibility of repair mortars and Hungarian porous limestones. Central Eur Geol 52(2):123–133

Szemerey-Kiss B, Török Á (2017a) Failure mechanisms of repair mortar stone interface assessed by pull-off strength tests. Bull Eng Geol Environ 76:159–167

Szemerey-Kiss B, Török Á (2017b) The effects of the different curing conditions and the role of added aggregate in the strength of repair mortars. Environ Earth Sci 76:284

Szemerey-Kiss B, Török Á, Siegesmund S (2013) The influence of binder/aggregate ratio on the properties and strength of repair mortars. Environ Earth Sci 69:1439–1449

Thomachot-Schneider C, Gommeaux M, Fronteau G, Oguchi CT, Eyssautier S, Kartheuser B (2010) A comparison of the properties and salt weathering susceptibility of natural and reconstituted stones of the Orval Abbey (Belgium). Environ Earth Sci 63:1447–1461

Thomachot-Schneider C, Gommeaux M, Fronteau G, Oguchi CT, Eyssautier S, Kartheuser B (2011) A comparison of the properties and salt weathering susceptibility of natural and reconstituted stones of the Orval Abbey (Belgium). Environ Earth Sci 63:1447–1461

Thomachot-Schneider C, Gommeaux M, Lelarge N, Conreux A, Kamel M, Bodnar JL, Vázquez P (2016) Relationship between Na2SO4 concentration and thermal response of reconstituted stone in the laboratory and on site. Environ Earth Sci 75:762

Török Á (2003) Surface strength and mineralogy of weathering crusts on limestone buildings in Budapest. Build Environ 38:1185–1192

Török Á, Rozgonyi N (2004) Morphology and mineralogy of weathering crusts on highly porous oolitic limestones, a case study from Budapest. Envir Geol 46:333–349

Török Á, Rozgonyi N, Prikryl R, Prikrylová J (2004) Leithakalk: the ornamental and building stone of Central Europe, an overview. In: Prikryl R (ed) Dimension stone. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 89–93

Van Balen K, Papayianni I, Van Hees R, Binda L, Waldum A (2005) Introduction to requirements for and functions and properties of repair mortars. Mat Struct 38:781–785

Vázquez P, Menéndez B, Denecker M, Thomachot-Schneider, C (2015) Comparison between petrophysical properties, durability and use of two limestones of the Paris region. In: Přikryl R, Török Á, Gomez-Heras M, Miskovsky K, Theodoridou M (eds) Sustainable use of traditional geomaterials in construction practice. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 416: 203–216

Yu S, Oguchi CT (2010) Role of pore size distribution in salt uptake, damage, and predicting salt susceptibility of eight types of Japanese building stones. Eng Geol 115:226–236

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Orsolya Farkas for her help in the porosity analyses.

Funding

The financial support of National Research, Development and Innovation (NKFI) Fund (ref. no. K 116532) is appreciated. The research was also realized with the support of the EU-funded project EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00021 (Hungarian University of Fine Arts). ÁT gratefully acknowledges the travel grant from Japan Geoscience Union to attend the Japan Geosciences Union Meeting 2017 that took place in Tokyo, Japan.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article since it is an ongoing project which has not been terminated yet. If additional data is needed, please contact the authors for data request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The tests were performed by BS-K in the laboratory. The evaluation and interpretation of test results were made by ÁT and BS-K. The paper was written by ÁT and BS-K. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Török, Á., Szemerey-Kiss, B. Freeze-thaw durability of repair mortars and porous limestone: compatibility issues. Prog Earth Planet Sci 6, 42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-019-0282-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-019-0282-1