Abstract

The Kuroshio Current is a major western boundary current controlled by the North Pacific Gyre. It brings warm subtropical waters from the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool to Japan exerting a major control on Asian climate. The Tsushima Current is a Kuroshio offshoot transporting warm water into the Japan Sea. Various proxies are used to determine the paleohistory of these currents. Sedimentological proxies such as reefs, bedforms, sediment source and sorting reveal paleocurrent strength and latitude. Proxies such as coral and mollusc assemblages reveal past shelfal current activity. Microfossil assemblages and organic/inorganic geochemical analyses determine paleo- sea surface temperature and salinity histories. Transportation of tropical palynomorphs and migrations of Indo-Pacific species to Japanese waters also reveal paleocurrent activity. The stratigraphic distribution of these proxies suggests the Kuroshio Current reached its present latitude (35 °N) by ~3 Ma when temperatures were 1 to 2 °C lower than present. At this time a weak Tsushima Current broke through Tsushima Strait entering the Japan Sea. Similar oceanic conditions persisted until ~2 Ma when crustal stretching deepened the Tsushima Strait allowing inflow during every interglacial. The onset of stronger interglacial/glacial cycles ~1 Ma was associated with increased North Pacific Gyre and Kuroshio Current intensity. This triggered Ryukyu Reef expansion when reefs reached their present latitude (~31 °N), thereafter the reef front advanced (~31 °N) and retreated (~25 °N) with each cycle. Foraminiferal proxy data suggests eastward deflection of the Kuroshio Current from its present path at 24 °N into the Pacific Ocean due to East Taiwan Channel restriction during the Last Glacial Maximum. Subsequently Kuroshio flow resumed its present trajectory during the Holocene. Ocean modeling and geochemical proxies show that the Kuroshio Current path may have been similar during glacials and interglacials, however the glacial mode of this current remains controversial. Paleohistorical studies form important analogues for current behavior with future climate change, however, there are insufficient studies at present in the region that may be used for this purpose. Modeling of the response of the Kuroshio Current to future global warming reveals that current velocity may increase by up to 0.3 m/sec associated with a northward migration of the Kuroshio Extension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Boundary currents and ocean gyres are important elements in heat transport on Earth; they fundamentally control the Earth’s climate. The Kuroshio Current is a major western boundary current in the western Pacific Ocean; it plays a key role in distributing heat from the tropics to the mid-latitudes and has been an important control on the climate of Northeast Asian for millions of years. This paper reviews evidence for the Pliocene to recent history of the Kuroshio Current and the Tsushima Current.

Oceanographic setting

The Kuroshio meaning “black stream” Current plays a key role in north Pacific circulation (Barkley 1970). Its “blackness” is related to the fact that it is derived from nutrient- and sediment-deficient subtropical North Pacific waters (Qiu 2001). Even though it occupies less than 0.1 % of the area of that ocean, it transports between 20 and 130 Sverdrups (1 Sverdrup (Sv) is 106 m3/s) of warm (16 to 28 °C) relatively high salinity water at speeds up to 130 cm/s (Qiu 2001; Wei 2006; Hsin et al. 2008). It travels northwards via a narrow band (<100 km wide and <1 km thick) that ultimately ends in the northern Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1). It plays a key role in modulating the climate of the northwest Pacific Ocean as it advects significant heat from the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool to the region forming the western arm of the North Pacific Gyre (Sawada and Handa 1998).

The surface oceanography of the Northwest Pacific Ocean adapted from Gallagher et al. (2009). The 200 m shelf edge bathymetric contour is indicated. The mean annual isotherm values are from Locarnini et al. (2006). The North Pacific currents are from Inoue (1989), Tomczak and Godfrey (1994), Qiu (2001), and Tada et al. (2014) ME Mindanao Eddy, HE Halmahera Eddy

The Kuroshio Current can be divided geographically into three regions: (1) the source region upstream of Tokara Strait, (2) south of Japan, and (3) the downstream Kuroshio Extension (Qiu 2001). It also bifurcates and travels into the Japan Sea via the Tsushima Strait.

-

1.

The source region: The Kuroshio Current is an offshoot of the North Equatorial Current that originates east of the Philippines at around 12°–13 °N (Fig. 1) where flow volume reaches 19 to 30 Sv (Qiu 2001). Occasionally, it intrudes into the Luzon Strait (21 °N, 121 °E) south of Taiwan; thereafter, it crosses the Yonaguni Depression via the East Taiwan Channel into the East China Sea (Fig. 2) and follows the edge of the continental shelf in the Okinawa Trough with flow volumes ranging from 22 to 27 Sv (Qiu 2001). It flows along the western part of the Okinawa Trough and leaves the continental slope via the Tokara Strait (Fig. 2) reaching the southern island of Japan at ~30 °N. Here, the current bifurcates with one main branch passing through the Tsushima Strait (where it feeds the Tsushima Current in the Japan Sea, Fig. 3) and the other flowing northwards into the northwest Pacific Ocean.

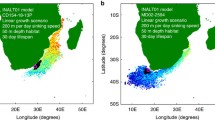

Fig. 2 The southern path of the Kuroshio Current showing the inferred extent of the Ryukyu Reefs in glacial and interglacial periods (adapted from Iryu et al. 2006)

Fig. 3 The path of the Tsushima and Kuroshio Current and Extension around Japan. Tsushima current nomenclature (TWC-1 to 3) is from Tada et al. (2014). The position of the Kuroshio meanders is adapted from Kubo et al. (2004). Base map adapted from General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) www.gebco.net. DSDP Site 302 is indicated BP Boso Peninsula, JJ Jeju Island, JO Joetsu, KI/IR Kozu-shima Island/Izu Ridge, MS Mamiya Strait, OK Oki Ridge/ODP Site 798, OI Oshima Island, OS Osami Strait, SI Sado Island, SS Soya Strait, TK Tohoku, TSG Tsuguru Strait

-

2.

South of Japan: as it crosses the Tokara Strait, Kuroshio flow volume increases from 30 to 55 Sv where the current is represented by the mean annual sea surface 16 °C isotherm (Qiu 2001). The net increase in flow rate may be due to anticyclonic gyre to its south or an occasional northeast flowing current. It follows several different meander paths (Qiu 2001) south of Honshu Island (Fig. 3).

-

3.

Downstream Kuroshio Extension: At 35 °N and 140 °E, the Kuroshio leaves the Japanese coast and flows eastward into the North Pacific Ocean as the Kuroshio Extension (Fig. 1). Flow volume in this extension can reach up to 130 Sv due to the existence of strong recirculation gyres to its south (Qiu 2001).

The Tsushima Current: The warm saline waters of the Kuroshio Current mix with freshwater in the East China Sea south of Japan (Qiu 2001) before flowing into the Japan Sea via the Tsushima Strait as the Tsushima Current (Figs. 1 and 3). The Japan Sea is a semi-enclosed marginal sea with an area of average depth of 1350 m and area of 1,000,000 km2. The sea is connected to the East China Sea through the Tsushima Strait, to the Pacific Ocean via the Tsugaru Strait, and to the Okhotsk Sea through the Soya and Mamiya straits (Fig. 3). All straits are narrower than 160 km and shallower than 130 m deep. Today, the only oceanic water flowing into the Japan Sea is the warm Tsushima Current. The current in the Tsushima Strait reaches surface velocities ranging from 0.3 to 0.4 m/s (up to 1 m/s during storms, Katoh et al. 1996) and flows northward along the western coast of Honshu Island. The volume of flow in the Tsushima Strait ranges from 2.6 to 1.1 Sv (Takikawa and Yoon 2005). Since the majority of the current flows out through the Tsugaru Strait to the Pacific Ocean, sea surface temperature (SST) decreases significantly around the strait. This is represented by a marine biogeographical boundary southwest coast of Hokkaido (Horikoshi 1962).

North of Tsugaru Strait, the remainder of the Tsushima Current flows northward along the western coast of Hokkaido Island (Fig. 3). A part of the current flows out through the Soya Strait to the Okhotsk Sea, while the remainder reaches the northern Japan Sea and becomes dense enough to sink to the bottom due to cooling and freezing (Suda 1932; Moriyasu 1972; Gamo and Horibe 1983). The sunken water mass is known as the Japan Sea Proper Water (JSPW) and has a low temperature (0.1–0.3 °C), low salinity (34), and high dissolved oxygen concentration (>210 μmol/kg). The deep-water region below the Tsushima Current is occupied by cold-water masses such as Japan Sea Intermediate Water (JSIW) and JSPW (Suda 1932; Moriyasu 1972). The thermocline between the Tsushima Current and JSIW is at about 150–160 m depth on the west side of Hokkaido. Benthic and nekton faunas change at this depth (Ogata 1972; Nishimura 1973, 1974; Tsuchida and Hayashi 1994; Kojima et al. 2001; Iguchi et al. 2007).

Proxies for the Kuroshio and Tsushima Currents

Modern biogeography and sedimentologic patterns in the Northwest Pacific Ocean are often directly related to the Kuroshio and Tsushima Current flow. Here, we focus primarily on the sedimentary features and biogeographic patterns that are likely to be preserved in the fossil record allowing the geological history of these oceanic features to be determined. We include the following fossilizable groups: macrofossils—corals and molluscs (bivalves and gastropods) and microfossils—diatoms, radiolarians, nannoplankton, ostracods, palynomorphs, and foraminifera. We add a summary of various geochemical proxies that may be used to determine “paleo” temperature and salinity of sea water that indicate Kuroshio and Tsushima Current activity in the past.

Sedimentary features

Bedforms and sediment sorting

The high-velocity Kuroshio Current (up to 130 cm/s) creates characteristic directional bedforms and well-sorted sand deposits in the shelfal regions (<400 m depth) around Japan. Sand streamers, sand waves, current lineations, and megaripples show ocean current directions south of Kyushu in the Osumi Strait (OS: Fig. 3: Ikehara 1989). Near Kozu-shima Island on the Izu Ridge (KI/IR: Fig. 3), Kuroshio Current velocities range from 0.3 to 0.5 m/s (up to 3 m/s) causing directional bedforms to form sand dune fields at depths between 200 and 400 m (Kubo et al. 2004). Elsewhere on the Pacific side of Japan, medium to large subaqueous sand dunes are propagated by oceanic currents at depths typically less than 100 m (Ikehara and Kinoshita 1994). In the Japan Sea, the southern branch of Tsushima Current generates directional asymmetric bedforms several meters high in shelf areas (<70 m water depth) in the Tsushima Strait (Fig. 3: Nishida and Ikehara 2013).

Transported palynomorphs

Transported palynomorph assemblages may be used to detect past Kuroshio Current activity. The tropical podocarp genus Phyllocladus is not present in Japan today; however, its presence in the fossil record off Kyushu suggests transportation by the Kuroshio Current from the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool (Kawahata and Ohshima 2004). Fluctuations in abundance of boreal sourced conifer pollen versus Ephedra from the Asian continent and other flora transported by the Kuroshio from the East China Sea have been used to determine paleolatitudinal variations in the Kuroshio Extension (Kawahata and Ohshima 2002); however, these Ephedra may also be windblown.

Coral reefs

The Kuroshio Current transports coral larvae and heat from the tropics to the southern half of mainland Japan (Iryu et al. 2006). It extends luxuriant coral reef development to ~31 °N (south of Kyushu, Fig. 2) in the Ryukyu Islands (Yamamoto et al. 2006) leading to a highly diverse hermatypic coral faunas in the region (Veron 1992; Veron and Minchin 1992). Typically, the present global latitudinal limit of coral reef development is constrained by the 18 °C winter maximum sea surface isotherm (Kleypas et al. 1999). However, small-scaled reefs have been found 2° north of this isotherm in the Tsushima Strait at 33° 48′ N representing the highest latitude reefs in the world (Yamano et al. 2001, 2012). Hermatypic coral diversity decreases northwards from over 400 species around Yaeyama Islands near Taiwan at ~24 °N (where the Kuroshio Current originates) to 24 species at ~35 °N (Tateyama, Boso Peninsula) where the Kuroshio Extension meets the Polar Front (Fig. 3; Veron 1992; Veron and Minchin 1992; Tsuchiya et al. 2004). Twenty-four species (Table 1) are present along the full path of the “main” Kuroshio Current (Veron 1992; Tsuchiya et al. 2004). Four species of corals are present in the Tsushima Strait (Table 1; Yamano et al. 2001, 2012).

Faunal and floral biogeography

This section outlines modern biogeographic indicators (Tables 1 and 2) of the Kuroshio and Tsushima currents.

Macrofossils

Most macroscopic faunal elements such as benthic molluscs and corals dominate the shelfal regions (<200 m) of the Northwest Pacific Ocean; as such, their geological utility as paleocurrent indices is primarily limited to strata formed at these shallow depths. The key Indo-Pacific coral species that indicate the Kuroshio Current have been described in the “Coral reefs” section; this section reviews the modern molluscan biography in the area.

Molluscs (bivalves and gastropods)

The planktic janthinid gastropod genus Hartungia is a well-known Kuroshio Current indicator (Tomida and Kitao 2002; Tomida et al. 2013). Several species are present along the full path of the “main” Kuroshio Current (Table 1) including Stellaria exutum, Cucullaea labiata, Jupiteria confuse, Cryptopecten vesiculosus, Cycladicama cumingi, Paphia amabilis, Paphia schnelliana, and Venus foveolata (Nobuhara 1993a, b). Molluscan species that are used as a proxy for the Tsushima Current are taxa that live in the area south of the southwestern Hokkaido, and live at the area shallower than 150–160 m depth off San-in and Hokuriku (Fig. 3) including Zeuxis castus, Stellaria exutum, Jupiteria gordonis, Crenulilimopsis oblonga, Cycladicama cumingi, and Paphia schnelliana (Kitamura and Ubukata 2003). These species are present in the Pacific coast area south of Boso Peninsula at 35 °N (BP: Fig. 3). Cold-water species (Acila insignis, Yoldia notabilis, Glycymeris yessoensis, Felaniella usta, Megangulus zyonoensis, and Mercenaria stimpsoni; Kitamura et al. 1994) are those living in the area north of the southern Hokkaido and/or deeper than 150–160 m depth off Sanin and Hokuriku (Fig. 3). These species are present north of 35 °N on the Pacific coast.

Microfossils

Microscopic floral and faunal elements are abundant in deep and shallow water sediment around Japan and the East China Sea. Similar to the mollusc and coral assemblages, most benthic microbiota (benthic foraminifera and ostracods) are confined to the sea bed in shelfal regions (<200 m) whereas other planktic forms (diatoms, radiolarians, nannoplankton, planktic foraminifera, and ostracods) are widely distributed in oceanic and shelfal sediment and are often key fossil Kuroshio or Tsushima Current indices (Tables 1 and 2).

Diatoms

Diatom paleoceanographic proxies have been statistically determined by comparing the distribution of diatom species in the surface sediments to factors such as primary production, SSTs (°C), salinity, and other physical–chemical parameters in modern surface waters (Kawai 1972, 1991; Yasuda et al. 1996; Masujima et al. 2003). The diatom temperature (Td) ratio was proposed by Kanaya and Koizumi (1966) to estimate sea surface water temperatures: Td = [Xw/(Xw + Xc)] × 100, where Xw is the frequency of warm-water species and Xc is that of cold-water species. Td ranges in value from 0 to 100. Going from the subarctic to tropical regions, Td becomes systematically larger, showing a positive correlation with sea surface water temperature over a given geographical site. Koizumi et al. (2004) redefined the Td ratio as Td′ ratio, applied strictly to oceanic holoplanktonic association: Td′ = [(Xw + XW)/(Xw + XW + Xc + XC)] × 100, where Xw and Xc, excluding Biddulphia (=Odontella) aurita, as originally proposed by Kanaya and Koizumi (1966) and XW and XC are supplemental species. In order to calibrate the Td′ ratio for paleo-temperatures, Koizumi (2008) performed regression analysis between the Td′ ratio (Table 2) in 123 surface sediment samples around the Japanese Islands in the northwest Pacific and the mean annual SSTs (°C) at the core sites. Equations to derived annual SST (°C) from Td′ ratio are different for the Tohoku area (y = 6.5711 × Td′0.273, R = 0.89946) than for the Japan Sea (y = 5.4069 × Td′26841, R = 0.89088). The annual paleo-SSTs (°C) in the Tohoku area were in general higher than those in the Japan Sea despite lower Td′ ratio because the warm-water species Fragilariopsis doliolus is abundant only in the Tsushima Warm Current in the Japan Sea. Td′-derived annual paleo-SSTs (°C) agree with the δ 18O of planktonic foraminiferal and UK’ 37 (an organic biomarker, see geochemical proxies below)-derived summer paleo-SSTs (°C) at sites off central Japan. Td′-SSTs (°C) fluctuate on centennial-to-millennial timescale, indicating a strong and regular flow of the Kuroshio–Kuroshio Extension and Tsushima Current during the Plio–Pleistocene. The Td′-SSTs (°C) in the Tohoku area off the northeast part of Honshu Island (Fig. 3) are generally higher than those in the Japan Sea despite lower Td′ values because the warm-water species Fragilariopsis doliolus is abundant only in the Tsushima Current in the Japan Sea. Those fluctuations are synchronous with abrupt climate events reported from the different paleoclimatic proxy records in many regions of the Northern Hemisphere (Tada et al. 1999; Koizumi and Sakamoto 2010; Koizumi and Yamamoto 2011). The Twt ratio or “paleoclimate curve” was created to interpret the Pliocene paleoclimatic changes in the northwest Pacific Ocean (Barron 1992). In the equation Twt = (Xw + 0.5Xt)/(Xc + Xt + Xw), Xw is the total number of subtropical to tropical (warm-water) species. Xt is the total number of warm transitional species (Thalassionema nitzschioides, Thalassiosira oestrupii, and Coscinodiscus radiatus) and Xc is the total number of subarctic to arctic (cold-water) species. Xw and Xc include such extinct Pliocene species as Fragilariopsis fossilis, Fragilariopsis reinholdii, Nitzschia jouseae, and Thalassiosira convexa as Xw, and Neodenticula kamtschatica and Neodenticula koizumii as Xc. Koizumi (Koizumi and Sakamoto 2012, 2013) added associated species and created the Td′ ratio of Koizumi (2008). This included additional extinct Pliocene species to those listed by Barron (1992) such as Nitzschia miocenica, Rhizosolenia praebergonii, Thalassiosira miocenica, and Thalassiosira praeconvexa as Xw and Actinocyclus oculatus, Proboscia curvirostris, and Thalassiosira nidulus as Xc. Thalassiosira oestrupii is converted from warm-water species in Td′ ratio to Xt in Twt because T. oestrupii prefers a relatively cooler environment (e.g., Ren et al. 2014).

Radiolarians

Tropical and subtropical radiolarian species in the North Pacific Ocean (Nigrini 1970; Lombari and Boden 1985; Yamauchi 1986; Motoyama and Nishimura 2005; Kamikuri et al. 2008) and the Japan Sea (Itaki 2003; Motoyama et al. submitted) are Kuroshio and Tsushima Current indicators. Nigrini (1970) reported distributions of 37 radiolarian species in 83 Holocene sediments widely collected from the North Pacific and classified into 6 recurrent groups which reflect surface circulation and upper water masses. Furthermore, she proposed Tr value as a climatic index based on cold, transition, and warm groups defined as the following equation:

Where Xw, Xt, and Xc indicate relative abundance of warm, transition, and cold water groups, respectively.

Yamauchi (1986) analyzed radiolarian assemblages in surface sediments from the northwestern Pacific along the Kuroshio and Oyashio Current paths and recognized three faunal groups relating to tropical, subtropical, and subarctic waters. He also proposed a climatic index SR value as the following equation based on each fauna;

Where

k = 1: subarctic fauna

k = 2: subtropical fauna

k = 3: tropical fauna

n k : number of specimens for each group

The SR value shows a close correlation with annual mean temperature at 50 to 200 m water depths.

In the northern part of the East China Sea, Chang et al. (2003) distinguished three radiolarian assemblages related to oceanographic patterns in the region. The mixed water assemblage is dominated by Tetrapyle circularis, Tetrapyle quadriloba, and Didymocyrtis tetrathalamus tetrathalamus and restricted to shelfal water. The Kuroshio Water assemblage is dominated by Lithelius minor, Dictyocoryne profunda, Stylodictya multispina, Acrosphaera spinosa, Dictyocoryne truncatum, Spongaster tetrars, Stylodictya arachnia, and Didymocyrtis tetrathalamus tetrathalamus, controlled by the Kuroshio Surface Water. And the transition assemblage dominated by Tetrapyle quadriloba and Monozonium pachystylum is associated with the Tsushima Current water.

Radiolarian faunal composition in the Japan Sea, which is characterized by deep-dwelling species associated with the JSPW and subtropical surface water species, is significantly different from assemblages of the adjacent mid-latitude North Pacific Ocean within the same latitudinal range (Itaki 2003; Motoyama et al. submitted). Motoyama et al. (submitted) reported that the observed assemblages in the sea include some subtropical elements, but many of the major temperate and subarctic elements of the North Pacific are excluded from the region. Because the Japan Sea is connected to the adjacent seas and ocean only via shallow straits, its surface waters are dominated by relatively warm waters derived from the East China Sea via the Tsushima Current, and the entry of oceanic waters from the adjacent North Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk is effectively blocked. This semi-enclosed geography is most likely responsible for the dominance of certain subtropical surface dwellers and for the near-absence of transitional and cool-water species from corresponding latitudes of the North Pacific.

Living radiolarians in the Japan Sea have been examined using plankton tows, and most of warm-water species are recognized in shallower depths (Itaki 2003; Ishitani and Takahashi 2007; Kurihara and Matsuoka 2010; Itaki et al. 2010). In the Tsushima Strait, radiolarian assemblages are similar with those in the East China Sea, while it is different from those in the northern Japan Sea (Itaki et al. 2010). According to Kurihara and Matsuoka (2010) who discussed seasonal variations of radiolarians in plankton samples from near the Sado Island (Fig. 3) of the eastern Japan Sea, warm-water species including Tetrapyle octacantha, Spongosphaera streptcantha, Pseudocubus obeliscus, and Dictyocoryne profunda group dominate the radiolarian assemblage from September to November. This result is consistent with results from a sediment trap experiment deployed in the Tsugaru area (Fig. 3), where the Tsushima Current flows into the northwest Pacific via the Tsugaru Strait (Itaki et al. 2008). These results imply that the warm-water species in the Japan Sea increase their abundance during summer to autumn associated with a stronger Tsushima Current.

Nannoplankton

The Florisphaera profunda/(F. profunda + Emiliania huxlei + Gephyrocapsa oceanica) (F-EG ratio) is used as a Kuroshio Current and nearshore proxy (Su and Wei 2005). Additional Kuroshio taxa include Calcidiscus leptoporous, Ceratolithus cristatus, Helicosphaera carteri, Oolithus fragilis, Rhabdosphaera clavigera, Thoracosphaera spp., and Umbellosphaera spp. (Chinzei et al. 1987; Su and Wei 2005). Key warm Tsushima Current indices in the Japan Sea include: G. oceanica, C. leptoporous, and H. carteri (Muza 1992).

Ostracods

Ikeya and Cronin (1993) analyzed modern ostracod assemblages around Japan and identified biogeographically significant taxa (Table 1). Typical Kuroshio Current assemblages can be divided into two: a Southwest Honshu, Kyushu assemblage with Neonesidea oligodentata, and an East China Sea assemblage with Cytheropteron rhombea, Cytheropteron uchioi, Argiloecia hanaii, and Munseyella japonica. Tsushima Current indicators include Krithe, Hirsutocythere hanaii, Cytheropteron miurense, and Bradlyea. Modern ostracods biofacies analyses in the Tsushima Strait and southwestern Japan Sea reveals that a distinctive biota (Biofacies B) migrates into the sea from the East China Sea via the Tsushima Current (Tanaka 2008). Key species include in Biofacies B Neonesidea oligodentata s.l., Schizocythere kishinouyei, Cytheropteron miurense, and Macrocypris decola.

Planktic foraminifera

Modern tropical and subtropical planktic foraminifera inhabit typically Kuroshio waters. One particular diagnostic taxon: Pulleniatina obliquiloculata is used extensively in paleoceanographic analyses (Li et al. 1997; Xu and Oda 1999; Ujiié and Ujiié 1999; Jian et al. 2000; Ujiié et al. 2003). Other species include Globigerinoides ruber, Globigerinoides sacculifer, Globigerinoides conglobatus, Globigerinella calida, Globorotalia hirsuta, Globorotalia menardii, and Sphaeroidinella dehiscens (Chinzei et al. 1987). The subtropical species Globigerinoides ruber migrates into the Japan Sea via the Tsushima Current (Kitamura et al. 2001; Domitsu and Oda 2006) and is a key Tsushima Current indicator. Globigerinoides ruber is the shallowest dwelling species that stays in surface waters during its life cycle (Fairbanks et al. 1982). Its lower limit of temperature tolerance is 19 °C (Hemleben et al. 1989). The switch from sinistrally coiled (colder) Neogloboquadrina pachyderma to dextral (warmer) coiled forms is also used to interpret Tsushima Current influence (Oba et al. 1991).

Benthic foraminifera

Biogeographic analyses shows that the following Indo-Pacific Warm Pool benthic foraminiferal taxa: Pseudorotalia indopacifica, Asterorotalia gaimardii, Asterorotalia spp., and Heterolepa margaritiferus migrate via the Kuroshio Current to shelfal regions in the East China Sea and around Japan (Gallagher et al. 2009). Two of these taxa (Asterorotalia gaimardii and Heterolepa margaritiferus) migrate into the southern shallow regions of the Japan Sea (Gallagher et al. 2009; Hoiles et al. 2012) via the Tsushima Current.

Geochemical proxies

Various geochemical indicators may be used to determine temperature and salinity variability in the surface ocean affected by the Kuroshio and Tsushima currents. The three techniques most commonly used are organic biomarkers, carbon/oxygen isotope analyses, and elemental proxies from calcareous microfossils (Mg/Ca):

Organic biomarkers

The UK’ 37 index is a proxy used to reconstruct sea surface temperatures (Rosell-Melé and McClymont 2007). This index is based on the relative abundance of di-unsaturated alkenones (C37:2) and tri-unsaturated alkenone (C37:3) in the sediment, and UK’ 37 stands for “unsaturated ketones with 37 carbon atoms”. Alkenones are abundant in marine sediment and produced primarily by phytoplankton (Haptophyceae including the nannoplankton Emiliania huxleyi) living in the euphotic zone; this proxy has been calibrated using a worldwide core top database (Rosell-Melé and McClymont 2007). The TEX86 index (TetraEther index of tetraethers with 86 carbon atoms) was proposed by Schouten et al. (2002) as seawater temperature index. It is based on the number of cyclopentane rings in glycol diakuyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGT’s) in the membrane lipids of archaebacteria such as Crenoarcheota in the upper 100 m of the water column (Rosell-Melé and McClymont 2007). Calibrations of TEX86 analyses of lipids in seabed sediment suggest that temperature estimates strongly correlate mean annual sea surface temperatures (Schouten et al. 2002).

Oxygen and carbon isotope analyses

Carbon and oxygen isotope analyses of calcareous foraminifera are routinely used in paleoceanographic analyses (see review in Ravelo and Hillaire-Marcel 2007). Typically, the ratios of stable oxygen and carbon isotopes are measured in foraminiferal carbonate expressed as δ 18O and δ 13C values in units per mil relative to VPDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite). Higher δ 18O values are caused by increased seawater evaporation (higher salinity), lower temperatures, and ice volume expansion (glacials) whereas lower values may reflect fresh water input, higher temperatures, and ice volume reduction (interglacials). Planktic foraminiferal δ 18O values reflect conditions in the upper 200 m of the water column whereas benthic foraminiferal δ 18O values seabed conditions.

Elemental proxies from calcareous microfossils (Mg/Ca)

While oxygen isotope analyses are often used for temperature estimates, δ 18O values vary due to salinity and ice volume effects. Another independent measure of seawater temperature is the Mg/Ca of marine calcite preserved in foraminiferal and ostracod shells (see review in Rosenthal 2007). As the substitution of Mg in calcite is endothermic, then Mg/Ca will reflect increasing temperatures. Estimates suggest that values of around 3 % Mg will substitute per °C (Rosenthal et al. 1997). Similar to oxygen isotope analyses, Mg/Ca of planktic foraminifera reflect sea surface paleotemperatures whereas Mg/Ca in ostracods and benthic foraminifera are used to determine seabed temperatures. Paleosalinity and past ice volume variability can be discerned using paired Mg/Ca and δ 18Ocalcite (Rosenthal 2007).

Geological history of the Kuroshio and Tsushima Currents

During the Neogene, the Kuroshio and Tsushima currents waxed and waned with the opening of gateways (the East Taiwan Channel and Tsushima Strait) due to tectonic and/or climate and sea level variability. This has resulted in various interpretations of the paleogeographic extent and intensity variability of the Kuroshio Current. The timing of the breakthrough of the Tsushima Current has also been investigated in detail. This section reviews the geological history of these currents and how they evolved through the Neogene. A summary of the key sections revealing Kuroshio and Tsushima Current history is in Table 3.

1. Pliocene to Middle Pleistocene history of the Kuroshio Current

In contrast to the many studies of the history of the late Pleistocene to Holocene Kuroshio Current, pre-late Pleistocene research is more limited (Table 3). The pre-early Pleistocene pathway of the Kuroshio Current is uncertain because tectonic evolution related to the opening of the Okinawa Trough and paleogeography of the Ryukyu Islands have not been well delineated. Seismic records suggest that the backarc rifting of the southern and northern Okinawa Trough was likely initiated in the early Pleistocene and in the late Miocene (Park et al. 1998; Gungor et al. 2012). Although the molecular biological data show that Taiwan and the southern Ryukyus were separated at 6–3 Ma (e.g., Koizumi et al. 2014), this age does not necessarily indicate the timing of inflow of the Kuroshio Current into the back-arc of the Ryukyu Islands. Extensive distribution of the Shimajiri Group, consisting mainly of fine siliciclastics derived from the Eurasian Continent, and its correlative sediments around the Ryukyu Islands, the Okinawa Trough, and East China Sea Shelf clearly indicate that the Kuroshio Current did not enter the back-arc side during the deposition of the group (~9–2.5 Ma). Once the Kuroshio Current flowed into the back-arc side, the Ryukyu Island became free from siliciclastic sedimentation. The paleoceanographic changes induced by stretching of the Okinawa Trough triggered carbonate sedimentation at ~1.4–2.0 Ma (e.g., Iryu et al. 2006), which is represented by that of upper Chinen Formation (shelf carbonate) and the Ryukyu Group (coral reef and associated shelf carbonates). Calcareous nannofossil assemblages of the Shimajiri Group in Okinawa-jima (~9–2.5 Ma), deposited in the forearc basin, record Kuroshio Current-related paleoceanographic variability. Eutrophism (high nutrients) prevailed from 5.3 to 3.5 Ma followed by oligotrophic (low-nutrient Kuroshio Current) conditions (Imai et al. 2013). This variability is also related to local tectonic movement.

The Kuroshio Current may have reached the Pacific coast of Japan by ~5.0 Ma with the migration of the tropical planktic gastropod species Janthina (Hartungia) typica in the Miyazaki Group in Kyushu (Tomida and Kitao 2002; Tomida et al. 2013). In addition, an ingression of strong Kuroshio flow is suggested ~3.0 Ma (Tomida et al. 2013).

Ikeya and Cronin (1993) analyzed Pliocene to Pleistocene fossil ostracods assemblages from strata on the east and west side of Japan and conclude that temperatures were 1–2 °C cooler during the Pliocene. However, these authors did not specifically identify “fossil” evidence of the Kuroshio and Tsushima Current activity.

The warm temperate to subtropical Kakegawa mollusc fauna typifies Pliocene to early Pleistocene strata on the Pacific Ocean side of Japan. This fauna includes the species: Anadara suzukii, Anadara castellata, Amussipecten praesignis, Amusium pleusonectens, Siphonalia declivis, Umbonium suchiense, Turritella perterbra, Venericardia panda, and Glycymeris nakamurai (Tsuchi and Shuto 1984; Ogasawara 1994). This biota is comparable to the modern Kuroshio fauna. The Indo-Pacific gastropod species Makiyamaia subdeclivis migrated to the Ryukyu Islands at the start of the Pliocene, thereafter reaching the south island of Japan by ~3.0 Ma (Tsuchi and Shuto 1984; Shuto 1990) suggesting that Kuroshio Current finally reached its present geographic extent during this time.

Indo-Pacific benthic foraminifera Pseudorotalia indopacifica, Asterorotalia gaimardii, and Heterolepa margaritiferus (Gallagher et al. 2009) are present in Pliocene to Recent strata in Japan (35 to 39 °N). Heterolepa margaritiferus first occurs in Okinawa in latest Pliocene strata younger than ~3.0 Ma. The distribution of A. gaimardii, H. margaritiferus, and P. indopacifica on the west coast of Japan at 35 °N suggests that the biogeographic realm of the Kuroshio Current (Gallagher et al. 2009) reached its present latitude by the latest Pliocene (~3.0 Ma). Similarly, Tsuchi (1997) and Ogasawara (1994, 2002) used Japanese molluscan biogeography (the Kakegawa mollusc fauna) to suggest Kuroshio Current intensification at ~3.0 Ma. Maier-Reimer et al. (1990) suggested that the increase in intensity of the North Pacific Gyre and related Kuroshio Current after 3.0 million years was related to the onset of the Northern Hemisphere Glaciation and the closure of the Central American seaway.

Benthic foraminiferal analyses of the Saegwipo Formation in Jeju Island in the East China Sea (JJ: Fig. 3) suggest fluctuating warm (Kuroshio) and cool phases from 3.58 to 0.78 Ma (Kang et al. 2010). After 0.78 Ma, warm Kuroshio Current waters dominated.

Ostracod and planktic foraminiferal analyses reveal cooling in a 2.8 to 2.5 Ma section on the west coast of Kyushu (Iwatani et al. 2012). Modern analog technique (MAT) reveals that Kuroshio influence decreased significantly across the Pliocene–Pleistocene boundary (~2.6 Ma) associated with global glacio-eustatic intensification (Iwatani et al. 2012).

The presence of Pleistocene fossil reefs in the Ryukyu Islands is directly related to Kuroshio Current intensity. The region was typified by a coral-bearing “ramp” from 1.65 Ma (Montaggioni et al. 2011); thereafter, the Ryukyu reefs expanded to their present latitudinal limit (Fig. 2) from 1.1 to 0.8 Ma (Yamamoto et al. 2006). This diachroneity and reef expansion may be related to a step-wise increase in Kuroshio Current intensity related to the magnitude of glacio-eustatic variability through the Middle Pleistocene Transition (Gallagher et al. 2014). In the past, the Ryukyu Reef front migrated to more southerly latitudes in glacial periods (~24 °N) and migrated north (~31 °N) during interglacials (Fig. 2: Iryu et al. 2006).

Facies analyses of a 700 ka sand ridge complex in the Kazusa Group on the west coast of Japan at 35 °N revealed strong paleo-Kuroshio activity (Ito and Horikawa 2000). Strong millennial-scale variations in current strength were interpreted to be related to global climate variable from the Middle to Late Pleistocene.

Radiolarians assemblages were analyzed in a 144 kyr sediment record off central Japan, where the Kuroshio Current diverts into the northwestern Pacific Ocean at ~36 °N (Yasudomi et al. 2014). Kuroshio species (all collosphaerids except Acrosphaera arktios, Didymocyrtis tetrathalamus, Euchitonia spp., Dictyocoryne spp., Octopyle stenozona–Tetrapyle octacantha) increased in abundance during MIS-1, 5a, 5c, and 5e. Yasudomi et al. (2014) also use the Tr value (the ratio of warm-water to the total of warm- and cool-water radiolarian species in an assemblage) to determine the varying dominance warm Kuroshio and cool Oyashio Currents in this region. Their analyses showed that a transitional surface water mass was replaced by a subtropical water mass between 131 and 125 ka.

Diatom analyses of a 150,000-year-old record in the Tohoku area reveal orbital scale glacial–interglacial environmental variability (Koizumi and Yamamoto 2010). High Td′-derived SSTs (°C) are estimated for MIS 5e with MIS 5e temperatures ~5 °C higher than present in nearshore regions and only ~1.5 °C higher in offshore regions. However, Td′-SSTs (°C) decline markedly in MIS 6 and at the MIS 6/5 boundary and event 5.2 in MIS 5b, correlating to Heinrich events 1–6 (Heinrich 1988). Td′-SSTs (°C) decrease during the Younger Dryas (YD) due to weakening Kuroshio–Kuroshio Extension intensity and are 7–9 °C lower than present-day values in the Tohoku area (Koizumi 2008). The early Holocene is transitional period characterized by a long-term increasing trend of temperatures with several cooling events, while the middle Holocene coincides with the Holocene hypsithermal period and is 1–2 °C warmer than the earlier and later period. The late Holocene neo-glacial period is marked by a generally decreasing trend of the Td′-SSTs (°C), reflecting the decreased solar insolation in the Northern Hemisphere summer (Koizumi and Sakamoto 2010).

2. Late Pleistocene to Holocene Kuroshio Current

Sawada and Handa (1998) used the UK’ 37 index to determine variability in Kuroshio flow intensity in 55,000-year-old marine sediment from south of Japan (33° to 31 °N). These authors relate the strong variability in these data to trade wind variability associated with changes in subtropic North Pacific high pressure.

Planktic foraminiferal assemblage data and oxygen isotope data are used to interpret the 20,000-year history of the Kuroshio Current in the Ryukyu Arc (Ujiié and Ujiié 1999; Ujiié et al. 2003; Jian et al. 2000). These authors and others (Li et al. 1997; Xu and Oda 1999) use Pulleniatina as a Kuroshio Current index. Jian et al. (2000) and Ujiié et al. (2003) interpret Pulleniatina minima events (PMEs) in the strata of this region to indicate times of reduced Kuroshio Current intensity since the LGM (Last Glacial Maximum, 22,000 years ago). Jian et al. (2000) suggests that the Kuroshio Current weakened from 4.6 to 2.7 cal. kyr BP possibly related to increased East Asian monsoon intensity and that Kuroshio intensity oscillated on a millennial scale with periodicities ranging from ca. 1500 to 800 years due to ocean thermohaline circulation variability. Other factors influencing Kuroshio Current intensity include variations in monsoonal forcing and freshwater input (Kao et al. 2006). The reduced Kuroshio Current influence in the region has also been attributed to the emergence of a land bridge between the Ryukyu Arc and Taiwan (the East Taiwan Channel: Fig. 2) that periodically deflected the Kuroshio Current to turn east at ~24 °N from during the early Holocene and the LGM (Ujiié et al. 1991, 2003). However, molecular biologic studies on reptiles and amphibians with limited mobility capability among isolated islands suggest that such a land bridge may not have existed (Ota 1998).

In addition, Lin et al. (2006) and Kubota et al. (2010) detected no change in SST or sea surface salinity during Pulleniatina minima, based on the Mg/Ca-derived temperatures using planktonic foraminifer from the East China Sea. Yamamoto et al. (2010) analyzed δ 18O of micro-bivalve from a submarine cave off the Okinawa Islands, Japan, and also detected no climate or hydrological anomaly variability associated with Pulleniatina minima. Kitamura et al. (2013) estimated that a mean annual surface water temperature was about 1 °C higher than during the Medieval Warm Period (900–1100 AD) and the Middle Holocene Climatic Optimum (9–5.5 ka BP) and that the recent warming is likely exceptional during the past 7000 years around Okinawa Islands, based on δ 18O of micro-bivalve from a submarine cave.

Matsushima (1984) reported that tropical molluscan species, which are presently living south of Kyushu (~30 °N) including Rhinoclavis kochi, Barbatia fusca, Saccostrea mordax, Periglypta chemnitzi, Dendostrea paulucciae, and Meropesta capillacea that migrated to ~36 °N 6.5–5.0 ka BP, indicating timing of the enhancement and northward expansion of the Kuroshio Current.

Detrital sediment and sorting analyses of Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg 195, Site 1202 (Fig. 2) suggest that Kuroshio inflow did not impinge on the Okinawa Trough during the LGM when fluvial siliciclastics from Yangtze River northwest of Taiwan dominated (Diekmann et al. 2008). The presence of sorted silt from northeast Taiwan suggests it re-entered the region after 12.2 ka BP. The current intensified from 11.2 to 9.5 ka BP as a response to rapid sea level rise (Diekmann et al. 2008).

A 13,000-year record of calcareous nannofossil assemblages from ODP Leg 195, Site 1202 (Fig. 2) reveals Kuroshio Current variability (Su and Wei 2005; Wei 2006). These authors use F-EG ratio as a proxy for the Kuroshio Current. Their analyses revealed significant floral change at 9 ka. Prior to 9 ka, Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa spp. dominated, whereas, after 9 ka, deep-dwelling Florisphaera profunda become common and Gephyrocapsa rare. This change is interpreted to indicate the reentry of the Kuroshio Current into the southern Okinawa Trough during the early Holocene.

Other studies used ocean models and geochemical data (Mg/Ca and δ 18O data) to document Kuroshio Current variability since the LGM (Kao et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2013). Kao et al. (2006) used a 3D ocean model to determine the effect of sea level and changing geomorphology on the Kuroshio Current in the Okinawa Trough. Their modeling suggests that as sea level fell, it reduced Kuroshio transport volume and changed the nature of the Kuroshio Current meanders. Lee et al. (2013) combined new oxygen isotope data with ocean modeling to suggest that the LGM and present path of the Kuroshio Current were similar and that glacial/interglacial sea level variability does not significantly alter the temperature, salinity, and path of the current. This contrasts to previous studies above (Ujiié et al. 2003) where the Kuroshio Current is interpreted to be deflected away from the Okinawa Trough into the Pacific at 24 °N due East Taiwan Channel closure during the LGM (Fig. 2).

If the Kuroshio Current was deflected at 22 °N into Pacific Ocean during the LGM (Ujiié et al. 2003), this would have caused the Kuroshio Extension to shift southward by at least 10° (Kawahata and Ohshima 2002). However, minor shifts (~3°) to the south in the latitudinal position of this extension have been interpreted in the central Pacific Ocean using palynofloral data (Hesse Rise; 34° 54.25′ N, 179° 42.18′ E) during glacial periods (Kawahata and Ohshima 2002). Furthermore, calculated SR values (the SST index of Yamauchi 1986) for late Pleistocene to Holocene radiolarian assemblages in a 30 °N to 40 °N north–south transect of sediment cores collected from off Japan in the northwestern Pacific Ocean also suggests a minor southerly shift of ~3° of Kuroshio Extension during LGM (Yamamoto et al. 2004).

The podocarp genus Phyllocladus is not present in Japan today; however, it is present in the Indonesian archipelago, and therefore, its presence in the northeastern part of the East China Sea (west of the Kyushu Island) during the LGM suggests transportation by the Kuroshio Current (Kawahata and Ohshima 2004).

3. Pliocene to Middle Pleistocene history of the Tsushima Current

Pliocene-early Pleistocene marine strata are well exposed along the coastal region of the Japanese Islands and yield abundant fossil molluscs (Kaseno and Matsuura 1965; Ogasawara 1977; Matsuura 1985; Chinzei 1986; Kanazawa 1990; Kitamura and Kondo 1990; Matsui 1990; Suzuki and Akamatsu 1994). Kitamura and Kimoto (2007) summarized the stratigraphic distribution of molluscan fossils in the Pliocene to lower Pleistocene marine strata along the Japan Sea coastal area (Amano et al. 1987, 1988, 1990, 2000; Amano and Kanno 1991; Arai et al. 1991, 1997; Cronin et al. 1994; Miwa et al. 2004) and the lower Pleistocene Omma Formation in the Hokuriku area (HO: Fig. 3: Kitamura and Kondo 1990; Kitamura 1991, 1994; Kitamura et al. 1994; Kitamura and Kawagoe 2006). Amano et al. (2008) documented Tsushima Current warm-water molluscan species and other cold-water species, which lived shallower than 100–120 m depth, in 12 horizons between tuff beds dated from 4 to 2.2 Ma in the Mita Formation in Yatsuo-machi of Toyama City near Joetsu (JO: Fig. 3). Sequence stratigraphic analysis was carried out on the Omma Formation (Kitamura 1998; Kitamura et al. 2001; Kitamura and Kawagoe 2006), and this provided an astronomically tuned a fossil record. The Omma Formation is up to 220 m thick and consists of 19 depositional sequences representing inner- to outer-shelf environments that are correlated to oxygen isotope stages (MIS) 56 to 21.3 (Kitamura 1998; Kitamura and Kimoto 2006). During the deposition of each sequence, the molluscan fauna changed from cold-water, upper-sublittoral species to warm-water (Tsushima Current), lower-sublittoral species, followed by a return to cold-water, upper-sublittoral species (Kitamura et al. 1994). Molluscan fossils are not present in MIS 25, 23, and 21.3, due to shell dissolution (Kitamura and Kawagoe 2006).

Based on stratigraphic distribution of warm-water species, Kitamura and Kimoto (2006) divided the history of the warm Tsushima Current from 3.5 to 0.8 Ma into two intervals (Fig. 4). The first interval from 3.5 to 1.7 Ma, the current periodically flowed into the Japan Sea at 3.2, 2.9, 2.4, and 1.9 Ma (MIS 69). Comparing these ages with δ 18O stratigraphy (Shackleton et al. 1995), the three older events may correlate with KM5 or 3, G17 or 15, and MIS 95 or 93, respectively. The second interval corresponds to a time when the Tsushima Current flowed during every interglacial highstand from 1.7 to 0.8 Ma (MIS 59–20), except for MIS 25, 23, and 21.3 (Fig. 4). The present southern channel in the Tsushima Strait (Fig. 3) is interpreted to have formed by MIS 59 (1.7 Ma) as the Tsushima Current began to flow during each interglacial period (Kitamura et al. 2001).

(i) The distribution of G. ruber and Tsushima Current molluscs in interglacials of the Omma Formation (adapted from Kitamura and Kimoto 2006) correlated to the LR04 benthic stack of Lisiecki and Raymo (2005). The red dots (1.6 to 1 Ma) are interglacials where migratory Indo-Pacific Warm Pool benthic foraminifera are present (Hoiles et al. 2012). Red dots at 0 and ~3 Ma are Warm Pool benthic foram ingressions described in Gallagher et al. (2009). Reconstructions of the paleogeography of the Tsushima Strait after 1.6 Ma (ii) and prior to 1.7 Ma (iii) adapted from Kitamura and Kimoto (2006)

Since sea levels in the interglacial periods at 3.3 to 2.5 Ma were up to 50 m higher than at present (Dwyer et al. 1995), the altitude of the southern part of the Japan Sea during 3.5 to 1.7 Ma was about 50 m above the present-day sea level. The altitude of the area might have decreased by 1.7 Ma. According to Kamata and Kodama (1999), crustal rotation and incipient rifting has also occurred in South Kyushu and the northern Okinawa Trough since 2 Ma. The authors interpreted that these events were caused by the transition to the westward convergence of the Philippine Sea plate. On the basis of timing and nature, Kitamura et al. (2001) assume that a change in the convergence direction of the Philippine Sea plate led to deepening and/or widening of the Tsushima Strait. It should be noted that the timing of these tectonically induced paleocenographic changes are roughly coeval with those in the Central and South Ryukyus, which triggered carbonate sedimentation. These suggest that the East China Sea and the Japan Sea became more influenced by the Kuroshio and Tsushima currents, respectively, from 1.5–2.0 Ma onwards due to the stretching of the Okinawa Trough and the deepening of the Tsushima Strait.

Inner- to outer-shelf environments in the southern Japan Sea may have been unsuitable for cold and the Tsushima Current molluscs from MIS 48 to 47, 44 to 43, and 32 to 31 (Kitamura et al. 2000; Kitamura 2004). These deglaciation MIS periods correspond to periods when eccentricity-modulated precession extremes were aligned with obliquity maxima and coincided with the three high peak of July solar insolation at 65 °N (495, 493, and 500 W/m2) between MIS 50 and 26. This implies that anomalously high seasonality induced by orbital-insolation cycles may have played an important role in establishment of non-analog molluscan fauna in the early Pleistocene Japan Sea. Kitamura (2004) used summer insolation data (Berger 1978) to suggest that such non-analog fauna would not established itself again in the next 150,000 years, while present global and/or regional climate systems are maintained.

Marine molluscan fossil records younger than 0.8 Ma are common in central and northern Japan (Omura 1980; Matsuura 1985; Nishimura 1996; Shirai and Tada 2000; Chiba and Sato 2014). These records show that the Tsushima Current flowed during MIS 9, 7, and 5 (Fig. 4).

Planktic foraminifera also reveal the long-term history of the Tsushima Current (Fig. 4). Kheradyar (1992) analyzed Pleistocene planktic distribution in the strata of ODP Site 798 at Oki Ridge (OK: Fig. 3). The sampling intervals were 30,000 years for strata ranging from 1.7 to 1.4 Ma and sample interval of 13,000 years in strata younger than 1.4 Ma. Only six horizons yield G. ruber from 1.7 to 0.8 Ma at Site 798, whereas in this interval, this species is present in 17 interglacial stages in the Omma Formation (Kitamura and Kimoto 2006) (Fig. 4). This discrepancy can be explained by either the low resolution of the sampling intervals, especially the interval from 1.7 to 1.4 Ma, or poor carbonate preservation during interglacial periods. In the Japan Sea, the calcium carbonate compensation depth (CCD) was less than 1,000 m during the last deglacial period (Oba et al. 1991). The shallower CCD was caused by oxic bottom conditions associated with a strong Tsushima Current inflow followed by increased JSPW production leading to a high dissolved oxygen level. These oceanic conditions may have caused poor carbonate preservation during many of the interglacial periods over the last 0.64 Ma (Kido et al. 2006).

The influx of G. ruber is at least 0.40 m lower than the lowest occurrence of Tsushima Current molluscs in the depositional sequence of the Omma Formation (Kitamura et al. 1999). This suggests that changes in bottom water on the upper continental shelf lagged behind changes in surface water associated with the influx of the Tsushima Current.

The stratigraphic distribution of Pliocene to early Pleistocene planktonic foraminifera is similar to that of the molluscan fossils (Kitamura and Kimoto 2006) and showing: (1) the Tsushima Current flowed at 3.2 Ma (MIS KM 5 or 3), 2.9 Ma (MIS G 17 or 15), and 1.9 Ma (MIS 59), in the 3.5–1.7 Ma interval; and (2) the current flowed at every interglacial highstand, except for MIS 25, 23, and 21.3, in the 1.71–0.8 Ma interval (Fig. 4). Miwa et al. (2004) analyzed planktonic foraminifers in 84 samples with 1–10 m sampling intervals in the Yabuta Formation, near Joestu (3.5–2.4 Ma). The authors identified one G. ruber horizon at 3.2 Ma (Fig. 4), confirming that the influence of the Tsushima Current was limited at narrow coastal area based on the molluscan fossil records.

The relative abundance of G. ruber in MIS 47, 43, and 31 is higher than in other interglacial stages from MIS 50 to 26 (1.5–1.0 Ma) in the early Pleistocene Omma Formation (Fig. 4: Kitamura and Kimoto 2007). As noted above, these interglacial stages coincided with the three high peak of July solar insolation at 65 °N between MIS 50 and 26.

The relative abundance of G. ruber at MIS 21.5 reaches 46 % in the Omma Formation and is higher than during MIS 47, 43, and 31 (Hoiles et al. 2012). Compared to the modern data of Domitsu and Oda (2006), this value is 40 % greater than today in the southernmost area of the Japan Sea. In ODP Site 798 (Oki Ridge: Fig. 3), the highest relative abundance of the species (6 %) is between the top of Jaramillo Subchron and the base of Brunhes Chron (Kheradyar 1992). The relative abundance of G. ruber is only 2 to 3 % in surface sediment from sites 150 km south of ODP Site 798. Boreal summer insolation at MIS 21.5 was lower than those of MIS 47, 43, and 31 (Berger 1992). In the LR04 δ 18O global isotope stack (Lisiecki and Raymo 2005), values are higher during this time compared to values during MIS 47, 43, 31, 11, 9, 5, and 1 (Fig. 4). Thus, the high relative abundance of G. ruber may be explained by its migration into the Japan Sea from the East China Sea rather than global climate change. Since G. ruber is a shallow-dwelling species, it is likely that wide and shallow Tsushima Strait significantly facilitated its preferential migration. Sea level during MIS 22 was lowest than those at any other time between MIS 56 and 21 (Bintanja et al. 2005; Kitamura and Kawagoe 2006; Elderfield et al. 2012; Rohling et al. 2014; Kitamura, in press). During the sea-level lowstand, the southern channel may have widened by erosion. After MIS 21, the deepening of the channel associated with erosion impeded the migration of G. ruber.

Kheradyar (1992) documented seven G. ruber horizons indicating Tsushima Current flow in 0.8 Ma and younger strata at ODP Site 798. However, these data cannot be correlated to marine isotope stages, due to the lack of a well-constrained chrono- and biostratigraphy.

Analyses of benthic foraminifera in the Omma Formation in the Japan Sea reveals common Indo-Pacific migratory species: Asterorotalia gaimardii, Asterorotalia concinna, Asterorotalia milletti, and Asterorotalia yabei during MIS 47 around 1.4 Ma (Hoiles et al. 2012). These taxa occur intermittently during most interglacial highstand periods from stages 55 to 29 showing a similar pattern to the planktic foraminifera and molluscan fossil assemblages described above. This is strong corroborating evidence for Tsushima inflow into the Japan Sea during each interglacial between 1.6 and 1.0 Ma (Hoiles et al. 2012).

Low-frequency and high-amplitude variations in diatom Twt and Td′-SSTs (°C) occur between 3.4 and 2.8 Ma in the Japan Sea (Koizumi and Yamamoto, in press), when Twt gradually increases due to a decreasing in cold-water species. Tsushima Current molluscs are present intermittently during this period (Fig. 4). After 2.8 Ma, the Twt ratio decreases markedly due to cooling near the Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary ~2.6 Ma. Twt and Td′-SSTs (°C) increase from 2.6 to 2.0 Ma due to a large decrease of cold-water species. The change from warm-water species to cold-water species denotes cooling from 1.19 to 1.17 Ma and 0.68 to 0.66 Ma during MIS 37–36 and MIS 17–16 when Tsushima Current molluscs and foraminifera are absent. Strong variations in cold-water species abundance occurs during the Jaramillo Subchron (MIS 30–26). The occurrence of warm-water species from 70–130 ka correlates to MIS 5 (Termination II), however, a peak of warm-water diatom species is not present during MIS 11 (Termination V).

Subtropical (Tsushima Current) radiolarian species such as Tetrapyle octacantha, Dictocoryne profunda, and Didymocyrtis tetrathalamus are present in strata younger than 1.7 Ma at DSDP site 302 (~40 °N) in the Japan Sea (Kamikuri and Motoyama 2007) coinciding with the influx of the subtropical planktonic foraminifera Globigerina ruber described above (Kitamura and Kimoto 2006).

Significant glacial–interglacial variability in radiolarian assemblages also occur in middle to late Pleistocene strata in the Japan Sea (Morley et al. 1986; Itaki 2001, 2007; Itaki et al. 2007). One particular Tsushima Current indicator, Tetrapyle octacantha group, increase in abundance during interglacial periods whereas it is absent or rare during the glacial periods due to Tsushima Current restriction.

4. Late Pleistocene to Holocene Tsushima Current

Cold-water molluscs Mytilus coruscus (11,050 ± 600 years BP; Emery et al. 1971), Macoma calcarea (15,740 ± 400 years BP; Emery et al. 1971), Mercenaria stimpsoni (13,130 ± 280 years BP; Chiji et al. 1981), and Patinopecten yessoensis (16,340 ± 420 years BP; Chiji et al. 1981) are present on the continental shelf in the Japan Sea off southwestern Japan. Fossil records of cored sediments at 132 m water depth off Sado Island, Japan (SI: Fig. 3), show that the molluscs Porterius dalli, Cyclocardia ferruginea, Tridonta alaskensis, and Puncturella nobilis were present prior to the initial inflow of the Tsushima Current at 9300 cal. BP (Kitamura et al. 2011). Subsequently, the modern molluscan fauna (dominated by Limopsis belcheri and Crenulilimopsis oblonga) first occurs at 5180 cal. BP in the study area. However, it is possible that the development of this modern molluscan fauna may relate to a reduction in terrigenous sediment influx and not directly related to Tsushima Current activity. A marked reduction in terrigenous sediment supply may be caused by enhanced vegetation and restabilized mountain slopes in the sediment source areas (Nakajima and Itaki 2007).

The oldest Tsushima Current molluscs from the latest Pleistocene–Holocene coastal plains of the Japan Sea are 8610 ± 100 year BP old Anodontia stearnsiana in incised valley fill on the Tsushima Islands (Saito et al. 1995) (Fig. 3). Tsushima Current molluscs with ages ranging from 7200 to 5000 years BP, 4200 to 3200 years BP, 2500 to 2300 years BP, and 1000 to 900 years BP are also present in the coastal area along Hokkaido ~43 °N (Kito et al. 1998; Matsushima 2010). This suggests periodic intensification of the northward inflow of the Tsushima Current.

G. ruber is present in 9300 cal. BP to recent strata in core from the Japan Sea suggesting continuous Tsushima Current inflow from this time (Domitsu and Oda 2006). These authors suggest that modern surface oceanic conditions in the southern Japan Sea had been established by 7300 cal. BP. Takata et al. (2006) used planktic foraminiferal assemblages to interpret periods of enhanced Tsushima Current from 8300–8000 and 7300–6800 years BP off Sanin (Fig. 3). The latter period corresponds with molluscan data that suggest Tsushima Current intensification 7200 to 5000 years BP (Matsushima 2010).

Warm-water radiolarians including Tetrapyle octacantha, Octopyle stenozona, Dictocoryne profunda, Dictocoryne truncatum, Didymocyrtis tetrathalamus, and Euchitonia flucata were rare during the last glacial period, and their initial migration via the Tsushima Current occurred at 10 ka and became abundant after 8 ka (Itaki 2001).

5. Kuroshio Current and Extension change with future climate change

The studies reviewed above reveal that current intensity and position has varied markedly over millions of year with changing greenhouse (Pliocene) to icehouse (Pleistocene) conditions. These studies may improve our understanding of current behavior with future climate change; however, there are insufficient millennial and annular fossil proxy studies in the Northwest Pacific that have the resolution required to directly compare with studies of modern oceanographic variability with climate change. In addition, there is limited atmospheric and ocean modeling of the response of the Kuroshio Current and Extension to future global warming (Sakamoto et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2012) suggesting that the current velocity will increase by up to 0.3 m/s (i.e., it may double in speed) as the North Pacific gyre intensifies. Furthermore, the position of the Kuroshio Extension has moved from an average position of ~34 °N northward to ~34.5 °N with global warming over the last century (Wu et al. 2012).

Conclusions

The Kuroshio Current is a major warm western boundary current in the western North Pacific. On the west side of the north Pacific Gyre, it plays a key role in distributing heat from the tropics to the pole and has been a major control on the climate of northeast Asian for millions of years. It bifurcates into the Japan Sea as the Tsushima Current and moderates Japanese climate. The geological history of these currents has been extensively investigated using various proxies. Sedimentological proxies such as reef, bedforms, palynological and sediment source distribution, and sediment sorting reveal current intensity/velocity and paleolatitude. Fossil coral and mollusc assemblage analyses provide strong evidence of the effect of these currents on paleoshelfal regions. Microfossils (planktic/benthic foraminifera, diatoms, radiolarians, and coccolith) assemblage variations are directly related to the strength and extent of past Kuroshio and Tsushima currents. Assemblage data combined with organic biomarker (UK’ 37, TEX86), stable isotope (δ 18O), and elemental (Mg/Ca) analyses are used to determine paleo-sea surface temperature and salinity histories in primarily oceanic archives. The transportation of tropical terrestrial palynomorphs and migrations of Indo-Pacific invertebrate macro- and microscopic species to Japanese waters reveal the paleocurrent intensity and latitudinal extent.

A review of stratigraphic distribution of these proxies suggests that the Kuroshio Current reached its present latitude (35 °N) by ~3 Ma when temperatures were 1 to 2 °C lower than present around Japan. At around this time, a weak Tsushima Current broke through Tsushima Strait entering the Japan Sea. Unlike Tsushima pathways today that extend into the center of the Japan Sea, early Tsushima Current was confined to coastal regions of Japan when sea level was up to 40 m higher than present. Limited stratigraphic data for the next 1 Ma suggests similar oceanic conditions with variable cooling and warm condition persisted until ~2 Ma. After 2 Ma, crustal stretching in the Okinawa Trough deepened Tsushima Strait facilitating inflow during every successive interglacial. The onset of stronger interglacial/glacial cycles at ~1 Ma was associated with increased North Pacific Gyre and Kuroshio Current intensity. This triggered Ryukyu Reef expansion, and these reefs reached their present latitude (~31 °N); thereafter, the reef front advanced (~31 °N) and retreated (~25 °N) with each successive cycle. Planktic foraminiferal proxy data (Pulleniatina minima events) from the south Okinawa Trough suggests eastward deflection of the Kuroshio Current from its present path at 24 °N into the Pacific Ocean due to East Taiwan Channel restriction during the Last Glacial Maximum. This deflection may have shifted the Kuroshio Extension and Polar Front by 10 °S southward to ~24 °N. Subsequently, Kuroshio flow resumed its present trajectory during the Holocene. However, ocean modeling and geochemical analyses (paired δ 18O, δ 13C, Mg/Ca analyses) of Late Pleistocene strata in the Okinawa Trough and East China Sea show that the Kuroshio Current path did not change between glacial and interglacial periods. Furthermore, analyses of radiolarian and terrestrial palynomorph assemblages in marine strata in the central North Pacific shows that the glacial/interglacial latitudinal position of Kuroshio Extension/Polar Front only shifted ~3° southward during glacial maxima.

Our synthesis shows that Kuroshio and Tsushima Current intensity and paleolatitude has varied significantly over millions of years with changing greenhouse (Pliocene) to icehouse (Pleistocene) conditions. Limited atmospheric and ocean modeling of the response of the Kuroshio Current and Extension to future global warming suggests that the Kuroshio flow velocity will increase by 0.3 m/s as the North Pacific gyre intensifies. Furthermore, the position of the Kuroshio Extension has shifted northwards by 0.5° with global warming over the last century. Further paleoceanographic analyses and modeling of the currents are required if we are to improve our understanding of how these modern oceanographic features of the northwest Pacific will respond to future climate change.

References

Amano K, Hamuro M, Sato T (2008) Influx of warm-water current to Japan Sea during the Pliocene-based on analyses of molluscan fauna from the Mita Formation in Yatsuo-machi of Toyama City. J Geol Soc Jpn 114:516–531 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Amano K, Ichikawa A, Koganezawa S (1988) Molluscan fauna from the Nadachi Formation around Osuga Bridge in Nadachi Town, Nishikubiki-gun. Studies on the molluscan fossils from the western part of Joetsu district, Niigata Prefecture (Part 3). Bulletin of Joetsu University of Education 7:63–75 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Amano K, Kanno S (1991) Composition and structure of Pliocene molluscan associations in the western part of Joetsu City, Niigata Prefecture. Fossils 51:1–14

Amano K, Kanno S, Ichikawa A, Yanagisawa Y (1987) Molluscan fauna from the Tanihama Formation in the western part of Joetsu City. Studies on the molluscan fossils from the western part of Joetsu district, Niigata Prefecture (Part 2). Bulletin of Joetsu University of Education 6:157–170 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Amano K, Kanno S, Nagai H, Sasabe N, Ban H (1990) Molluscan fauna from the Kawazume Formation in the western part of Joetsu City. Studies on the molluscan fossils from the western part of Joetsu district, Niigata Prefecture (Part 5). Bulletin of Joetsu University of Education 9:67–75 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Amano K, Sato T, Koike T (2000) Paleoceanographic conditions during the middle Pliocene in the central part of Japan Sea Borderland. Molluscan fauna from the Kuwae Formation in Shibata City, Niigata Prefecture, central Japan. J Geol Soc Jpn 106:883–894 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Arai K, Konishi K, Sakai H (1991) Sedimentary cyclicities and their implications of the Junicho Formation (late Pliocene-early Pleistocene), Central Honshu, Japan. Scientific Reports of Kanazawa University 36:49–82

Arai K, Sakai H, Konishi K (1997) High-resolution rock-magnetic variability in shallow marine sediment: a sensitive paleoclimate metronome. Sediment Geol 110:7–23

Barkley RA (1970) The Kuroshio Current. Sci J 6:54–60

Barron JA (1992) Pliocene paleoclimatic interpretation of DSDP Site 580 (NW Pacific) using diatoms. Mar Micropaleontol 20(1):23–44

Berger AL (1978) Long-term variations of caloric insolation resulting from the earth’s orbital elements. Quatern Res 9:139–167

Berger AL (1992) Orbital variations and insolation database. IGBP PAGES/World Data Center-A for Paleoclimatology Data Contribution Series # 92–007. NOAA/NGDC Paleoclimatology Program, Boulder CO, USA, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data/datasets, edited

Bintanja R, van de Wal RSW, Oerlemans J (2005) Modelled atmospheric temperatures and global sea levels over the past million years. Nature 437:125–128

Chang F, Li T, Zhuang L, Li T, Yan J, Cao Q, Cang S (2003) Radiolarian fauna in surface sediments of the northeastern East China Sea. Mar Micropaleontol 48:169–204

Chiba T, Sato S (2014) Recognizing cryptic environmental changes by using paleoecology and taphonomy of Pleistocene bivalve assemblages in the Oga Peninsula, northern Japan. Quatern Res 81:21–34

Chiji M, Okamoto K, Yamauchi S, Konda I, Ishii H, Inokuchi H, Hayashida A, Tshigaki T (1981) Preliminary report of the Tansei Maru cruise KT-79-8 (the Southwestern Japan Sea). Bulletin of the Japan Sea Research Institute Kanazawa University 13:167–169 (in Japanese)

Chinzei K (1986) Faunal succession and geographic distribution of the Neogene molluscan faunas in Japan. Palaeontolgical Society Japan Special Papers 29:17–32

Chinzei K, Fujioka K, Kitazato H, Koizumi I, Oba T, Oda M, Okada H, Sakai T, Tanimura Y (1987) Postglacial environmental change of the Pacific Ocean off the coasts of central Japan. Mar Micropaleontol 11(4):273–291

Cronin TM, Kitamura A, Ikeya N, Watanabe M, Kamiya T (1994) Late Pliocene climate change 3.4–2.3 Ma: paleoceanographic record from the Yabuta Formation, Sea of Japan. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 108:437–455

Diekmann B, Hofmann J, Henrich R, Fütterer DK, Röhl U, Wei K-Y (2008) Detrital sediment supply in the southern Okinawa trough and its relation to sea-level and Kuroshio dynamics during the late quaternary. Mar Geol 255(1):83–95

Domitsu H, Oda M (2006) Linkages between surface and deep circulations in the southern Japan Sea during the last 27,000 years: evidence from planktic foraminiferal assemblages and stable isotope records. Mar Micropalaeontol 61:155–170

Dwyer GS, Cronin TM, Baker PA, Raymo ME, Buzas JS, Correge T (1995) North Atlantic deepwater temperature change during late Pliocene and late quaternary climatic cycles. Science 270:1347–1351

Elderfield H, Ferretti P, Greaves M, Crowhurst S, McCave IN, Hodell D, Piotrowski AM (2012) Evolution of ocean temperature and ice volume through the mid-Pleistocene climate transition. Science 337:704–709

Emery KO, Niino H, Sullivan B (1971) Post-Pleistocene levels of the East China Sea. In: Turekian KK (ed) The late Cenozoic glacial age. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 381–390

Fairbanks RC, Sverdlove M, Free R, Wiebe PH, Bé AWH (1982) Vertical distribution and isotopic fractionation of living planktonic foraminifer from the Panama Basin. Nature 298:841–844

Gallagher SJ, Wallace MW, Hoiles PW, Southwood JM (2014) Seismic and stratigraphic evidence for reef expansion and onset of aridity on the Northwest Shelf of Australia during the Pleistocene. Mar Pet Geol 57:470–481

Gallagher SJ, Wallace MW, Li CL, Kinna B, Bye JT, Akimoto K, Torii M (2009) Neogene history of the West Pacific warm pool, Kuroshio and Leeuwin currents. Paleoceanography 24(1):PA1206

Gamo T, Horibe Y (1983) Abyssal circulation in the Japan Sea. J Oceanogr Soc Jpn 39:220–230

Gungor A, Lee GH, Kim H-G, Han H-C, Kang M-H, Kim J, Sunwoo D (2012) Structural characteristics of the northern Okinawa Trough and adjacent areas from regional seismic reflection data: geologic and tectonic implications. Tectonophysics 522–523:198–207

Heinrich H (1988) Origin and consequences of cyclic ice rafting in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean during the past 130,000 years. Quatern Res 29:142–152

Hemleben C, Spindler M, Anderson OR (1989) Modern planktonic foraminifera. Springer, New York

Hoiles PW, Gallagher SJ, Kitamura A, Southwood JM (2012) The evolution of the Tsushima Current during the early Pleistocene in the Japan Sea: an example from Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 47. Global Planet Change 92–93:162–178

Horikoshi M (1962) Warm temperate region and coastal-water area in the marine biogeography of the shallow sea system around the Japanese islands. Quatern Res (Daiyonki-Kenkyu) 2:117–124 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Hsin Y-C, Wu CR and Shaw PT (2008) Spatial and temporal variations of the Kuroshio east of Taiwan, 1982–2005: a numerical study. J Geophys Res 113(C04002). doi:10.1029/2007JC004485

Iguchi A, Takai S, Ueno M, Maeda T, Minami T, Hayashi I (2007) Comparative analysis on the genetic population structures of the deep-sea whelks Buccinum tsubai and Neptunea constricta in the Japan Sea. Mar Biol 151:31–39

Ikehara K (1989) The Kuroshio-generated bedform system in the Osumi Strait, southern Kyushu, Japan. In: Taira A, Masuda F (eds) Sedimentary facies in the active plate margin. Terra Scientific Pub. Co, Tokyo, pp 261–273

Ikehara K, Kinoshita Y (1994) Distribution and origin of subaqueous dunes on the shelf of Japan. Mar Geol 120(1):75–87

Ikeya N and Cronin TM (1993) Quantitative Analysis of Ostracoda and Water Masses around Japan: Application to Pliocene and Pleistocene Paleoceanography. Micropaleontology 399(3):263–281.

Imai R, Sato T, Iryu Y (2013) Chronological and paleoceanographic constraints of Miocene to Pliocene “mud sea” in the Ryukyu Islands (southwestern Japan) based on calcareous nannofossil assemblages. Island Arc 22(4):522–537

Inoue Y (1989) Northwest Pacific foraminifera as paleoenvironmental indicators. Science Reports of the Institute of Geoscience, University of Tsukuba, Section B: Geological Sciences 10:57–162

Iryu Y, Matsuda H, Machiyama H, Piller WE, Quinn TM, Mutti M (2006) Introductory perspective on the COREF Project. Island Arc 15(4):393–406

Ishitani Y, Takahashi K (2007) The vertical distribution of Radiolaria in the waters surrounding Japan. Mar Micropaleontol 65:113–136

Itaki T (2001) Radiolarian faunal changes in the eastern Japan Sea during the last 30 kyr. News of Osaka Micropaleontologists Special Volume 12:359–374, in Japanese with English abstract

Itaki T (2003) Depth-related radiolarian assemblage in the water-column and surface sediments of the Japan Sea. Mar Micropaleontol 47:253–270

Itaki T (2007) Historical changes of deep-sea radiolarians in the Japan Sea during the last 640 kyrs. Fossils 82:43–51 (in Japanese)

Itaki T, Komatsu N, Motoyama I (2007) Orbital- and millennial-scale changes of radiolarian assemblages during the last 220 kyrs in the Japan Sea. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 247:115–130

Itaki T, Minoshima K, Kawahata H (2008) Radiolarian flux at an IMAGES site at the western margin of the subarctic Pacific and its seasonal relationship to the Oyashio Cold and Tsugaru Warm currents. Mar Geol 255:131–148

Itaki T, Kimoto K, Hasegawa S (2010) Polycystine radiolarians in the Tsushima Strait in 2006 autumn. Paleontological Research 14:19–32

Ito M, Horikawa K (2000) Millennial-to decadal-scale fluctuation in the paleo-Kuroshio Current documented in the Middle Pleistocene shelf succession on the Boso Peninsula, Japan. Sediment Geol 137(1):1–8

Iwatani H, Irizuki T, Hayashi H (2012) Global cooling in marine climates and local tectonic events in Southwest Japan at the Plio–Pleistocene boundary. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 350:1–18

Jian Z, Wang P, Saito Y, Wang J, Pflaumann U, Oba T, Cheng X (2000) Holocene variability of the Kuroshio current in the Okinawa Trough, northwestern Pacific Ocean. Earth Planet Sci Lett 184(1):305–319

Kamata H, Kodama K (1999) Volcanic history and tectonics of the Southwest Japan Arc. Island Arc 8:393–403

Kamikuri S, Motoyama I (2007) Radiolarian assemblage and environmental changes in the Japan Sea since the Late Miocene. Fossils (The Palaeontological Society of Japan) 82:35–42 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Kamikuri S, Motoyama I, Nishimura N (2008) Radiolarian assemblages in surface sediments along longitude 175°E in the Pacific Ocean. Mar Micropaleontol 69:151–172

Kanaya T, Koizumi I (1966) Interpretation of diatom thanatocoenoses from the North Pacific applied to a study of core, V20-130. Tohoku Univ, Sci Rep, 2nd Ser (Geol) 37(2):89–130

Kanazawa K (1990) Early Pleistocene glacio-eustatic sea-level fluctuations as deduced from periodic changes in cold- and warm-water molluscan associations in the Shimokita Peninsula, Northeast Japan. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 79:263–273

Kang S, Lim D, Kim S-Y (2010) Benthic foraminiferal assemblage of Seogwipo Formation in Jeju Island, South Sea of Korea: implication for late Pliocene to early Pleistocene cold episode in the northwestern Pacific margin. Quat Int 225(1):138–146

Kao SJ, Wu C-R, Hsin Y-C and Dai M (2006) Effects of sea level change on the upstream Kuroshio Current through the Okinawa Trough. Geophys Res Lett 33(L16604). doi:10.1029/2006GL026822

Kaseno Y, Matsuura N (1965) Pliocene shells from the Omma Formation around Kanazawa City, Japan. Scientific Reports of Kanazawa University 10:27–62

Katoh O, Morinaga K, Miyaji K, Teshima K (1996) Branching and joining of the Tsushima Current around the Oki Islands. J Oceanogr 52:747–761

Kawahata H, Ohshima H (2002) Small latitudinal shift in the Kuroshio Extension (Central Pacific) during glacial times: evidence from pollen transport. Quat Sci Rev 21(14):1705–1717

Kawahata H, Ohshima H (2004) Vegetation and environmental record in the northern East China Sea during the late Pleistocene. Global Planet Change 41(3):251–273

Kawai H (1972) Hydrography of the Kuroshio extension. In: Stommel H, Yoshida K (eds) Kuroshio-its physical aspects. University of Tokyo, Tokyo, pp 235–352

Kawai H (1991) The existing conditions of research on the relationship current and biology. In: Kawai H (ed) Existing conditions of researches into currents and biology–fisheries oceanography. Kyoto University Press, Kyoto, pp 2–4

Kheradyar T (1992) Pleistocene planktonic foraminiferal assemblages and paleotemperature fluctuations in Japan Sea, Site 798. In: Pisciotto KA, Ingle JC, von Breymann MT, Barron J (eds) Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, scientific results. Ocean Drilling Program, College Station, pp 457–470

Kido Y, Koshikawa T, Tada R (2006) Rapid and quantitative major element analysis method for wet fine-grained sediments using an XRF mixroscanner. Mar Geol 229:209–225

Kitamura A (1991) Paleoenvironmental transition at 1.2 Ma in the Omma Formation. Central Japan Transactions and Proceedings of the Palaeontological Society of Japan 162:767–780

Kitamura A (1994) Depositional sequences caused by glacio-eustatic sea-level changes in the upper part of the early Pleistocene Omma Formation. J Geol Soc Jpn 100:463–476, Japanese with English abstract

Kitamura A (1998) Glaucony and carbonate grains as indicators of the condensed section: Omma Formation, Japan. Sediment Geol 122:151–163

Kitamura A (2004) Effects of seasonality, forced by orbital-insolation cycles, on offshore molluscan faunal change during rapid warming in the Japan Sea. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 203:169–178