Abstract

Background

The understanding of high mortality associated with intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC) remains limited. While Candida is considered a harmless colonizer in the digestive tract, its role as a true pathogen in IAC is still debated. Evidence regarding Candida virulence in the human peritoneal fluid are lacking. We hypothesized that during IAC, Candida albicans develops virulence factors to survive to new environmental conditions. The objective of this observational exploratory monocentric study is to investigate the influence of peritoneal fluid (PF) on the expression of C. albicans virulence using a multimodal approach.

Materials and methods

A standardized inoculum of a C. albicans (3.106 UFC/mL) reference strain (SC5314) was introduced in vitro into various PF samples obtained from critically ill patients with intra-abdominal infection. Ascitic fluids (AFs) and Sabouraud medium (SBD) were used as control groups. Optical microscopy and conventional culture techniques were employed to assess the morphological changes and growth of C. albicans. Reverse transcriptase qPCR was utilized to quantify the expression levels of five virulence genes. The metabolic production of C. albicans was measured using the calScreener™ technology.

Results

A total of 26 PF samples from patients with secondary peritonitis were included in the study. Critically ill patients were mostly male (73%) with a median age of 58 years admitted for urgent surgery (78%). Peritonitis was mostly hospital-acquired (81%), including 13 post-operative peritonitis (50%). The infected PF samples predominantly exhibited polymicrobial composition. The findings revealed substantial variability in C. albicans growth and morphological changes in the PF compared to ascitic fluid. Virulence gene expression and metabolic production were dependent on the specific PF sample and the presence of bacterial coinfection.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence of C. albicans virulence expression in the peritoneal fluid. The observed variability in virulence expression suggests that it is influenced by the composition of PF and the presence of bacterial coinfection. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the complex dynamics of intra-abdominal candidiasis and advocate for personalized approach for IAC patients.

Trial registration https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (NCT05264571; February 22, 2022)

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

This study is the first to demonstrate the expression of Candida albicans virulence in human peritoneal fluid.

-

The expression of Candida albicans virulence in peritoneal fluid shows significant variability among critically ill patients with intra-abdominal infection.

-

The composition of peritoneal fluid and bacterial coinfection may influence the expression of Candida albicans virulence.

-

These findings emphasize the imperative to reevaluate the delineation of intra-abdominal candidiasis, with due consideration to the virulence expression exhibited by isolated Candida.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intra-abdominal infections are the second cause of sepsis and septic shock in the critically ill patients [1]. These infections encompass a range of types, with generalized peritonitis associated with the highest mortality rates [2]. In addition to bacterial pathogens, Candida species can also be involved in intra-abdominal infections. Currently, the diagnosis of intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC) is based on the presence of Candida in abdominal samples obtained during surgery [3, 4]. IAC accounts for a substantial proportion of invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients [5], occurring in both hospital- and community-acquired in 13–33% and 7–32% of cases, respectively [6]. Candida albicans is the primary causative agent of IAC [7, 8]. The mortality rate associated with IAC ranges from 20 to 50% [2, 9]. However, the reasons behind the high mortality in IAC remain unclear, especially in the absence of candidemia.

While Candida is considered a harmless colonizer in the digestive tract, its role as a true pathogen in IAC is still debated [10]. Isolating Candida from the peritoneal fluid (PF) without candidemia poses challenges in determining its pathogenicity and its association with mortality [11, 12]. Antifungal treatment studies in IAC have yielded inconsistent results regarding patient survival [13,14,15,16,17]. Some researchers consider the presence of Candida as a marker of disease severity [18]. Despite this, there is a lack of studies investigating Candida virulence in human PF.

C. albicans possesses various virulence mechanisms that enable tissue invasion, evasion of host defenses, and biofilm formation [19, 20]. However, most of these mechanisms have been studied in the context of candidemia, where Candida must overcome natural barriers to reach the bloodstream [21]. The course of infection in IAC differs, as the breach in the intestinal wall is caused by anastomosis leakage, necrosis, or perforation. Notably, candidemia is only associated with a minority of IAC cases [7], suggesting alternative triggers for C. albicans virulence.

In this study, our hypothesis was that in the context of secondary peritonitis, C. albicans develops virulence factors as a means of adapting to the new environmental conditions presented by the peritoneal fluid. In addition, we explored whether this adaptation was influenced by interactions with other microorganisms. Using a step-by-step and multimodal approach, this experimental study aims to evaluate the influence of PF issued from critically ill patients with intra-abdominal infections on C. albicans virulence.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was an observational exploratory monocentric study conducted at the Université de Lorraine, in the laboratory “Stress, Immunité et Pathogènes” (SIMPA, UR 7300), and at the University Hospital of Nancy from January 2021 to December 2022. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov under the number NCT05264571 (retrospectively registered 22 February 2022). This study was an ancillary study of a non-interventional prospective cohort study (the pBDG2 study, prospective evaluation of 1.3 β-d-glucan in the PF for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal candidiasis in the critically ill patients NCT03997929). The pBDG2 study included critically ill patients with intra-abdominal infections requiring abdominal surgery and allowed the constitution of a biological collection of peritoneal fluid samples.

Abdominal samples

The samples used in this study consisted of PF obtained from critically ill patients with intra-abdominal infections, and ascitic fluid (AF) obtained from critically ill patients with decompensated cirrhosis of non-infectious origin. AF has the advantage to be the accessible sterile, biological fluid with the closest composition to PF. These samples were obtained after routine analysis, and the remaining samples were selected for use in this study. All selected samples underwent microbiological analysis to detect the presence of bacteria and fungi.

To be eligible for selection, PF samples had to meet the following criteria: absence of Candida infection, derived from the initial abdominal surgery (excluding relaparotomy), obtained from the University Hospital of Nancy, and having a minimum volume of 5 mL.

Strains and media

The SC5314 reference C. albicans strain was used for all experiments, as its growth and genome are well-described in the literature [22]. For the evaluation of metabolic production, clinical strains of various bacteria were utilized.

For all experiments (phenotype, molecular, metabolic) three different media were employed: two as controls (Sabouraud and AF) and the PF. Sabouraud medium (SBD) served as a control medium for assessing growth, morphology, and metabolic profile. AF was obtained as a non-infected clinical sample from humans, and its lack of infection was confirmed through microbiological analysis (direct examination, conventional culture) and cytology (neutrophil count < 250/mm3). PF, on the other hand, could exhibit different characteristics and might be infected with various bacteria, both positive and negative gram. Since AF and PF were collected consecutively, they were stored at − 20 °C until each experiment period. All analyses were conducted in duplicate or triplicate.

Phenotypic approach

Inoculation of C. albicans in the different media

C. albicans SC5314 strain was inoculated in triplicate into one mL of the three different types of media (SBD, AF, PF) at an optical density (OD) of 0.3 nm, corresponding to approximately 3.106 colonies of C. albicans per millilitre (C. albicans/mL) of media. Control wells containing only the media without C. albicans were also included on the same 24-well plate to confirm the absence of contamination. All OD measurements were performed at 600 nm with a UV/Visible spectrophotometer P4 from VWR® (Radnor, Pennsylvania, United States).

Observation of C. albicans in each media

The 24-well plate was inoculated and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 300 RPM for 24 h. First, the morphology of C. albicans was observed under a light microscope at hourly intervals for the initial 8 h, followed by observations at H16 and H24. The analysis of morphology was conducted by ME, in collaboration with the members of the SIMPA laboratory. The results were subsequently validated by MM, an expert in mycology, who was blinded to the sample types. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus or consultation with a third independent researcher. Second, C. albicans growth was assessed by inoculating 10 μL from each well onto SBD dextrose agar, and the colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. To facilitate counting, 1000-fold dilutions of each inoculated well were prepared beforehand.

Composition of ascitic and peritoneal fluid

Each liquid received biochemical measurements (protein, glucose, pH) and cell counts using flow cytometry.

Molecular approach

C. albicans inoculation in the different media followed the same protocol as for phenotypic evaluation, with an overnight culture of 24 h before gene expression analysis.

Genes of interest

The primers utilized for reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RTq-PCR) analysis can be found in supplementary material (Additional file 1: Table S1). The five virulence genes of interest are UME6, ALS3, SFL2, HWP1 and ECE1. Basically, UME6 and SFL2 have a role in Candida filamentation. ALS3, HWP1, and ECE1, have a role in adhesion and epithelial cells damage. Please refer to supplementary material for the precise role of each gene.

RNA extraction

After the 24-h overnight culture, the samples were centrifuged to retain only the cell pellet. The cell pellet was then washed twice with 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, the PBS was removed, leaving behind only the cell pellet.

RNA extraction was performed using the FASTPREP® lysis technology (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, California, United States), following the manufacturer’s program specifically designed for Candida cells. To assess the quality and measure the RNA concentration, each sample was analyzed using a Nanodrop 2000 system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Total RNA extraction was carried out using the Monarch Genomic RNA Purification Kit (New England Biolabs® Inc., Ipswich, MA, United States) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse transcription

Reverse transcription was performed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit from Qiagen® (Germantown, Maryland, United States) following the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were prepared in two steps: genomic DNA removal and reverse transcription. The reverse transcription process was carried out using a thermocycler, following the specified protocol. The steps involved were as follows: annealing at 25 °C for 3 min, reverse transcription at 45 °C for 10 min, and inactivation at 85 °C for 5 min.

Amplification by PCR

The qPCR was performed in MicroAmp Optical 96-Well Reaction Plates (Applied Biosystems) using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la Coquette, France). Please refer to supplementary material S1 for the details regarding the primers and cycling protocol. Relative transcript levels and the fold change of SFL2, UME6, ALS3, HWP1 and ECE1 were determined following the ΔΔCT method [23]. All analyses were performed in duplicate with negative control samples. The level of expression was compared among the PF against AF level expression, to ensure the comparability in a clinical sample.

Metabolic approach using the calscreener™ technology

The calscreener™ technology

The metabolic evaluation was conducted using the calScreener™ technology (Symcel AB, Solna, Sweden) (Fig. 1) [24]. This technology utilizes isothermal calorimetry to measure the heat flow generated by living cells in real time. It can be applied to various microorganisms and media types. The calScreener™ device provides continuous real-time data over an extended duration. Different parameters can be evaluated directly from the curve, such as time to activity, time to peak or decay time. Analysis of the heat production is carried out using the dedicated software, calView® (Symcel AB, Solna, Sweden). Each specific pathogen generates a distinct growth pattern in the kinetic data, enabling identification of the pathogen type [25]. This technology utilizes 48-well microtiter cell culture plates, accommodating 32 biological samples and 16 thermodynamic internal reference positions.

Metabolic analysis

For the inoculation of C. albicans in the different media, the same protocol was followed as for the phenotypic and molecular evaluation. The overnight culture of C. albicans for 24 h was used before transferring the samples into the calScreener™. It should be noted that all AF and PF samples used were confirmed to be free of pathogens to serve as controls for the added inoculum. Each culture was then appropriately diluted, either 1/100 or 1/1000, in each medium as per the recommendations provided by Symcel. Subsequently, 200 µL of each medium, in duplicate, were transferred to the calScreener™ sample handling system. Real-time measurement of the heat produced from each calWells was carried out at 37 ± 0.001 °C in the calScreener™ up to 48 h. The presence of an active pathogen is associated with a metabolic activity > 5 microW, according to the manufacturer. The remaining samples in the microtitre plate were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to ensure the presence of expected pathogens.

Statistical analysis

Due to the exploratory and observational nature of this study, a predetermined calculation of the required sample size was not performed. The sample size was based on the availability of PF samples during the study period. Descriptive statistics were computed using GraphPad Prism version 9 (Boston, Massachusetts, United States). The statistics included counts, means, standard deviation, medians, quartiles, and interquartile ranges (IQR), as deemed appropriate for the analysis.

To compare the heat production between samples during the metabolic evaluation, ordinary one-way ANOVA and Mann–Whitney test were employed. This statistical analysis was used to assess any significant differences in heat production among the samples. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

During the designated study period, a total of 129 critically ill patients who underwent intra-abdominal surgery were enrolled as participants. Among these patients, 26 PF samples met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study. Details regarding patient characteristics are provided in Table 1. PF characteristics’ (macroscopic aspect and bacterial culture) are provided in Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S2. Overall, patients with intra-abdominal infections were mostly male [n = 19 (73%)] with a median age of 58 years admitted for urgent surgery [n = 20 (78%)]. All the PF samples were associated with cases of secondary peritonitis, including 13 post-operative peritonitis (50%). The infected PF samples predominantly exhibited polymicrobial composition. The majority of patients from whom AF samples were collected were post-operative decompensated cirrhosis [n = 6 (60%)].

Different PF samples were utilized for the three distinct approaches due to the step-by-step nature of the study, limited volume of collected samples per patient, and availability of the calScreener™.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the sample selection and allocation process for the three different analyses conducted in the study.

Phenotypic approach

Figure 2A illustrates the morphology of C. albicans in the different media used in the study. The SBD medium served as the control for each plate layout. No contamination was observed. The microscopic examination of C. albicans after growth in SBD (n = 10) revealed a consistent presence of unicellular ovoid yeast forms without any hyphae. This morphology remained unchanged throughout the various manipulations.

Phenotypic approach: morphology and growth of C. albicans according to the media. A morphology of C. albicans depending on the media, after 24 h. B Growth of C. albicans depending on the media, after 24 h (Box plot showing median, interquartile range and min–max value). More images are available in the supplementary materials (Additional file 1: Figure S1)

After inoculating C. albicans from the SBD wells onto SBD dextrose agar, the colony count results demonstrated a consistent increase in the number of C. albicans colonies from H0 to H24, as shown in Fig. 2B. At H0, the median number of colonies of C. albicans per mL at H0 was 3,010,000 (n = 10, IQR = 2.5), which then increased to 32,150,000 (n = 10, IQR = 173.2) at H24. This indicates a 10.7-fold median increase in the number of C. albicans colonies from H0 to H24 (IQR = 0.44).

In AF, no contamination was observed. The microscopic examination of C. albicans after growth in AF revealed a transition from oval yeast forms to filamentous hyphae forms. The hyphae tended to form conglomerates. After inoculating C. albicans from AF wells onto SBD dextrose agar, the colony count results showed a consistent increase in the number of C. albicans colonies from H0 to H24, as depicted in Fig. 2B. The median number of C. albicans colonies per mL at H0 was 2,770,000 (n = 5, IQR = 25.0), which then increased to 7,500,000 (n = 10, IQR = 94.0) at H24. This represents a 2.37-fold median increase in the number of C. albicans colonies from H0 to H24 (IQR = 0.28).

In PF, no contamination was observed. Table 2 provides an overview of the phenotypes of C. albicans observed in PF samples 1 to 10. The microscopic examination of C. albicans after growth in PF exhibited variability, with observations of yeasts alone, hyphae, and both with and without conglomerates (Fig. 2A). After inoculating C. albicans from PF wells onto SBD dextrose agar, the colony count results demonstrated variable changes in the number of C. albicans colonies from H0 to H24 (Fig. 2B). For instance, the number of C. albicans colonies per mL could be up to 21 times higher at H24 compared to H0 in PF2, while in PF7, the number decreased between H0 and H24. The median number of C. albicans colonies per mL at H0 was 2,557,000 (n = 10, IQR = 155), and at H24, it was 2,325,000 (n = 10, IQR = 309.87). In summary, there was a 1.48-fold median increase (n = 10, IQR = 3.11) in the number of C. albicans colonies per mL from H0.

Composition of fluid used for the phenotypic approach

In case of PF (n = 10/10), we noted a median/IQR count of leucocytes of 42.9 [13.2–72.8] G/L mostly consisting of neutrophils (median 39.0 [13.0–72.9] G/L), a median protein of 38.0 [29.7–44.7] g/l, a median glucose of 0.30 [0.22–0.47] mmol/L, and a median pH of 8.50 [8.25–8.67]. As for AF (n = 5/10), the median count of leucocytes was 0.12 [0.08–0.16] G/L, the median protein was 12.0 [12.0–17.0] g/l, the median glucose was 6.50 [5.9–7.9] mmol/L, and the median pH was 7.50 [7.50–7.70]. For a comprehensive breakdown of these measurements, refer to the Additional file 1: Table S3.

Molecular approach

The expression of C. albicans genes was analysed and log-transformed in 13 different PFs. Figure 3 depicts the heatmap of ECE1 HWP1, UME6, ALS3, and SFL2 expression in the different PFs compared to those in AF. The heat map showed the highly variable expression of these five genes, reflecting the different impacts of each PF on C. albicans gene expression.

Heat map of virulence expression gene in PF 11 to 23. Legend: heat map showing log-transformed quantitative genes expression of C. albicans grown in different peritoneal fluids. Gene expression of C. albicans in peritoneal fluids is compared with ascitic fluid. Relative gene expression was measured by RTqPCR using the ΔΔCT method. PF: peritoneal fluid

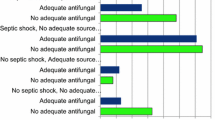

Metabolic approach

In Fig. 4A, the total heat production was compared between different media when the same amount of C. albicans was inoculated alone. It was observed that SBD medium produced the highest amount of heat, with a mean of 18.03 J, which was statistically significant compared to other media (p < 0.0001). The heat production in AF was lower than in PF, and there was a statistically significant difference between AF and PF25 as well as PF26 (p < 0.001). Among the three different PFs evaluated, there was also a statistically significant difference in heat production: PF24 had a mean of 3.83 J, PF25 had a mean of 6.62 J, and PF26 had a mean of 15.37 J (p = 0.0261, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001).

Heat production of C. albicans alone and combined with different bacteria, according to the media. Heat production is expressed as mean and standard deviation. A Total heat production after 48 h of C. albicans depending on the type of media (Sabouraud, ascitic fluid, peritoneal fluid number 24–26). B–D Total heat production after 48 h of C. albicans with different bacteria (B Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus in PF24; C Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter cloacae in PF25; D Bacteroides fragilis, in PF26). PF: peritoneal fluid

In Fig. 4B–D, the heat production was analysed for samples combining C. albicans and bacteria. Apart from one combination (PF25, C. albicans with E. cloacae), the differences in metabolic production between C. albicans alone and in conjunction with bacteria were statistically significant across all other combinations. These associations yielded both increased metabolic rates (notably with E. coli, S. aureus, and B. fragilis) and decreased metabolic rates (particularly with P. aeruginosa and E. cloacae).

In terms of comparing pathogen associations within the same PF (Additional file 1: Figure S2), the combination of C. albicans with S. aureus generated a higher heat production than the combination of C. albicans with E. coli (p < 0.01) in PF24. Similarly, in PF25, the combination of C. albicans with E. cloacae resulted in higher heat production than the combination of C. albicans with P. aeruginosa (p < 0.05).

The difference between samples heat production, time to activity, time to peak, time to decay, metabolic activity between samples and pathogen combination are described in supplementary materials (Additional file 1: Table S4, Figure S3). No contamination and survival of all involved yeast and bacterial strains were confirmed after inoculation of the remaining sample on culture plates.

Discussion

This study represents the first reported investigation into the expression of C. albicans virulence in human peritoneal fluid using three distinct approaches that consistently yielded similar results. The findings of this study could challenge the notion that C. albicans should be solely regarded as a harmless colonizer in PF and highlight its potential pathogenic role. Moreover, the study demonstrates that the expression of C. albicans virulence factors in PF seems to be highly variable and influenced by the specific characteristics of the fluid as well as the presence of bacteria.

The phenotype approach confirmed the presence of hyphae forms of C. albicans in the PF. The ability of C. albicans to transition from yeast to hyphal forms is considered a crucial virulence attribute [20]. This transition confers C. albicans with the potential to penetrate epithelial and intestinal barriers and evade the immune system [19] which are well-established mechanisms in candidemia [26]. However, in the present study, the presence of hyphal forms was observed in the PF without the requirement of barrier crossing. The switch to hyphal forms is known to be triggered by various factors, including interactions with bacteria, immune cells, and environmental conditions, such as temperature and pH [27,28,29]. The variability in the composition of PF may explain the observed variation in C. albicans forms.

In this context, it remains challenging to pinpoint specific parameters within the PF that are accountable for the observed variability. The composition of the PF in secondary peritonitis predominantly featured a significant presence of immune cells, primarily neutrophils, alongside relatively elevated protein levels and diminished glucose concentrations. Despite our efforts, we were unable to detect a discernible pattern in the PF composition that correlated with a higher occurrence of virulence expression. This could be attributed to the limitations imposed by the sample size. Consequently, the need for further investigations becomes apparent, necessitating a larger sample pool and a more comprehensive analysis that encompasses factors, such as the specific types of proteins (such as immunoglobulins), sources of carbon (for instance, lactate), and the immune components (comprising cell types and cytokines) at play. In addition, some PF samples exhibited a mixture of hyphal and yeast forms, a phenomenon previously reported. The yeast form is believed to facilitate dissemination, while the hyphal form is associated with tissue damage [30].

The evaluation of different genes involved in the mechanisms of virulence in C. albicans revealed that the hyphal switch is not the sole mechanism contributing to its virulence [31]. For instance, HWP1, an adhesin gene, is essential for mucosal epithelial cell adhesion and biofilm formation [32]. ECE1 is essential for the synthesis of candidalysin, a cytolytic peptide toxin that directly damages host epithelial membranes [33]. Molecular analyses confirmed the observations made during the phenotypic experiments, indicating that the expression of these five C. albicans virulence genes was highly variable depending on the composition of the PF. The PF components appear to influence both the phenotype of C. albicans and the expression of its virulence genes.

The metabolic analyses conducted in the study revealed significant variability in heat production depending on the composition of the PF and the presence of bacteria. Heat production is known to be associated with microbial growth and activities, and it is considered to be more accurate and sensitive compared to standard culture methods [34, 35]. Interactions between Candida and bacteria have been previously demonstrated [36]. In animal model, the intra-peritoneal co-injection of C. albicans and Staphylococcus aureus led to higher mortality in mice compared to single infections [37]. Co-infection with E. coli and C. albicans resulted in higher mortality in mice compared to mono-infection [38]. Regarding heat production, the presence of bacteria yielded diverse outcomes in terms of metabolic rates. Combinations with E. coli, S. aureus, and B. fragilis led to heightened metabolic rates, while pairings with P. aeruginosa and E. cloacae resulted in reduced metabolic rates. Analysing the area under the curve of metabolic production (refer to Additional file 1: Figure S3), only the association with B. fragilis demonstrated a sustained signal at 24 h, indicating a potential synergistic activity that might be attributed to biofilm formation. Previous experimental studies have demonstrated that C. albicans contributes to the survival of B. fragilis through biofilm formation, creating an anaerobic microenvironment that promotes the growth and persistence of B. fragilis [39].

The findings of this study are consistent with two recent animal studies conducted in mice, which also explored the influence of PF on the virulence of C. albicans [40, 41]. Lima et al. reported that the presence of fecal material in the peritoneal cavity reduced the invasiveness of C. albicans [40]. Cheng et al. demonstrated that the PF composition, including local pH and molecular signatures, influenced the expression of virulence genes, indicating a role in modulating C. albicans virulence during abscess formation [41].

Major strength of this study is its unique approach in assessing the pathogenicity of C. albicans using PF obtained from human intra-abdominal infections, which provides more relevant insights compared to animal models, which have certain limitations. For instance, these models often involve immunosuppressed mice, which may not fully represent the immune status of human patients with intra-abdominal infections. In addition, the administration of C. albicans through intra-peritoneal injection in animal models does not replicate the complete spectrum of pathogenesis observed in human cases, including the interactions between the gut microbiota and the host before the breach of the intestinal barrier. Finally, the immune, inflammatory, and metabolic responses to infection in mice differ significantly from the human phenotype of sepsis [42].

Limitations

We acknowledge limitations in our study. First, the sample size was relatively small, and we were unable to perform combined analyses using the triple approach on the same sample. This limitation arose due to the stepwise approach of the study, limited sample volume, and restricted access to the calScreener™ equipment. Second, the extraction of RNA from human PF was particularly challenging and had not been previously attempted. Overcoming these technical difficulties was a notable achievement of our study. Finally, the use of the calScreener™ for PF and Candida species was a novel application. Indeed, previous studies have been conducted using the calScreener™ equipment with bacteria [25], but its application to PF or Candida species has not been explored before. We had to dedicate some PF samples to test its feasibility and reliability, as well as to configure the inoculum accurately for ensuring comparability between samples.

This study was observational, and it revealed a high variability in the expression of C. albicans virulence and metabolic profiles. Additional investigations are necessary to uncover the precise factors contributing to the variation in C. albicans virulence expression. While bacteria were introduced as a modifiable element, it remains challenging to pinpoint the exact constituents of the peritoneal fluid responsible for driving this virulence expression.

It is important to note that this study focused specifically on C. albicans, and the results may not be applicable to other Candida species with different virulence mechanisms, such as C. glabrata. In addition, the study only examined samples from secondary peritonitis, limiting conclusions regarding primary and tertiary peritonitis. Spontaneous fungal peritonitis is a primary peritonitis which shares commonalities with IAC. Of note, the treatment necessity, especially in cirrhotic patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure is debated [43, 44]. Spontaneous fungal peritonitis necessitates a translocation of Candida across the gastrointestinal tract mucosa into the peritoneal cavity, a process exacerbated by factors, such as immunosuppression or malnutrition. The evaluation of virulence expression of Candida during spontaneous fungal peritonitis may help to address the question regarding treatment.

Certainly, the next step would involve assessing the virulence of clinical strains of Candida obtained from critically ill patients with IAC and correlating the expression of virulence factors with clinical outcomes. However, before conducting these analyses, further optimization is necessary for the molecular and metabolic evaluations. RNA extraction from PF proved to be challenging, as did ensuring an adequate quantity of inoculum for metabolic assessment. One advantage of this experimental study was the ability to control both the inoculum and the experimental conditions.

Conclusion

This study provides the first evidence of C. albicans virulence in human peritoneal fluid. The expression of C. albicans virulence was found to be highly variable in PF samples from critically ill patients with intra-abdominal infection. These findings could challenge the current understanding of IAC, which primarily relies on clinical signs of infection and positive Candida cultures. Further research is needed to identify the specific components of PF that promote C. albicans virulence. The next important step is to determine the factors that trigger the transition of Candida from a harmless colonizer to a life-threatening pathogen, allowing for targeted treatment in critically ill patients with invasive candidiasis. In addition, there is a need for studies investigating the immune response in the context of IAC involving the human population. Indeed, the ability of the immune system to clear the peritoneum from pathogen including Candida is of high interest to understand clinical outcomes, such as mortality. Besides, Candida can escape the immune system among other with hyphae transformation and biofilm formation. Thus, to better understand changes in Candida virulence, all components (media, bacteria, immunity) must be evaluated. These studies will contribute to the development of personalized medicine approaches for managing invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, but some restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study (calScreener™), and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of all authors.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Actin

- ALS:

-

Agglutinin-like sequence

- AF:

-

Ascitic fluid

- ECE:

-

Extent of cell elongation

- HWP:

-

Hyphal wall protein

- IAC:

-

Intra-abdominal candidiasis

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interval quartile range

- OD:

-

Optical density

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PF:

-

Peritoneal fluid

- RTqPCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SBD:

-

Sabouraud medium

- SIMPA:

-

Stress, Immunité, Pathogènes

- TEF:

-

Translation elongation factor

References

Vincent J-L, Sakr Y, Singer M et al (2020) Prevalence and outcomes of infection among patients in intensive care units in 2017. JAMA 323:1478–1487. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2717

Blot S, Antonelli M, Arvaniti K et al (2019) Epidemiology of intra-abdominal infection and sepsis in critically ill patients: “AbSeS”, a multinational observational cohort study and ESICM Trials Group Project. Intensive Care Med 45:1703–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05819-3

Montravers P, Dupont H, Eggimann P (2013) Intra-abdominal candidiasis: the guidelines—forgotten non-candidemic invasive candidiasis. Intensive Care Med 39:2226–2230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3134-2

Bassetti M, Azoulay E, Kullberg B-J et al (2021) EORTC/MSGERC definitions of invasive fungal diseases: summary of activities of the intensive care unit working group. Clin Infect Dis 72:S121–S127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1751

Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, Vena A et al (2019) Incidence and outcome of invasive candidiasis in intensive care units (ICUs) in Europe: results of the EUCANDICU project. Crit Care 23:219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2497-3

Nourry É, Wallet F, Darien M et al (2023) Use of 1,3-beta-d-glucan concentration in peritoneal fluid for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal candidiasis in critically ill patients. Med Mycol 61:myad029. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myad029

Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR et al (2022) Risk factors for intra-abdominal candidiasis in intensive care units: results from EUCANDICU study. Infect Dis Ther 11:827–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00585-6

Leroy O, Bailly S, Gangneux J-P et al (2016) Systemic antifungal therapy for proven or suspected invasive candidiasis: the AmarCAND 2 study. Ann Intensive Care 6:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-015-0103-7

De Waele J, Lipman J, Sakr Y et al (2014) Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome. BMC Infect Dis 14:420. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-420

Sandven P, Qvist H, Skovlund E et al (2002) Significance of Candida recovered from intraoperative specimens in patients with intra-abdominal perforations. Crit Care Med 30:541–547. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200203000-00008

Garnacho-Montero J, Díaz-Martín A, Cantón-Bulnes L et al (2018) Initial antifungal strategy reduces mortality in critically ill patients with candidemia: a propensity score-adjusted analysis of a multicenter study. Crit Care Med 46:384–393. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002867

Bassetti M, Vena A, Meroi M et al (2020) Factors associated with the development of septic shock in patients with candidemia: a post hoc analysis from two prospective cohorts. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2793-y

Sartelli M, Coccolini F, Kluger Y et al (2021) WSES/GAIS/SIS-E/WSIS/AAST global clinical pathways for patients with intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg 16:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-021-00387-8

de Ruiter J, Weel J, Manusama E et al (2009) The epidemiology of intra-abdominal flora in critically ill patients with secondary and tertiary abdominal sepsis. Infection 37:522–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-009-8249-6

Dupont H, Paugam-Burtz C, Muller-Serieys C et al (2002) Predictive factors of mortality due to polymicrobial peritonitis with Candida isolation in peritoneal fluid in critically ill patients. Arch Surg 137:1341–1346

Lagunes L, Rey-Pérez A, Martín-Gómez MT et al (2017) Association between source control and mortality in 258 patients with intra-abdominal candidiasis: a retrospective multi-centric analysis comparing intensive care versus surgical wards in Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-016-2775-9

Vergidis P, Clancy CJ, Shields RK et al (2016) Intra-abdominal candidiasis: the importance of early source control and antifungal treatment. PLoS ONE 11:e0153247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153247

Montravers P, Dupont H, Gauzit R et al (2006) Candida as a risk factor for mortality in peritonitis. Crit Care Med 34:646–652. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000201889.39443.D2

Galocha M, Pais P, Cavalheiro M et al (2019) Divergent approaches to virulence in C. albicans and C. glabrata: two sides of the same coin. Int J Mol Sci 20:2345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20092345

Calderone RA, Fonzi WA (2001) Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol 9:327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7

Hoyer LL, Cota E (2016) Candida albicans agglutinin-like sequence (Als) family vignettes: a review of als protein structure and function. Front Microbiol 7:280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00280

Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H et al (2004) The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:7329–7334. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0401648101

dMIQE Group, Huggett JF (2020) The digital MIQE guidelines update: minimum information for publication of quantitative digital PCR experiments for 2020. Clin Chem 66:1012–1029. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa125

Wadsö I, Hallén D, Jansson M et al (2017) A well-plate format isothermal multi-channel microcalorimeter for monitoring the activity of living cells and tissues. Thermochim Acta 652:141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2017.03.010

Beilharz K, Kragh KN, Fritz B et al (2023) Protocol to assess metabolic activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by measuring heat flow using isothermal calorimetry. STAR Protoc 4:102269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102269

Goyer M, Loiselet A, Bon F et al (2016) Intestinal cell tight junctions limit invasion of Candida albicans through active penetration and endocytosis in the early stages of the interaction of the fungus with the intestinal barrier. PLoS ONE 11:e0149159. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149159

Höfs S, Mogavero S, Hube B (2016) Interaction of Candida albicans with host cells: virulence factors, host defense, escape strategies, and the microbiota. J Microbiol 54:149–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-016-5514-0

Paroli M, Caccavale R, Fiorillo MT et al (2022) The double game played by Th17 cells in infection: host defense and immunopathology. Pathogens 11:1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11121547

Ballou ER, Avelar GM, Childers DS et al (2016) Lactate signalling regulates fungal β-glucan masking and immune evasion. Nat Microbiol 2:16238. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.238

Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL (2003) Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot Cell 2:1053–1060. https://doi.org/10.1128/EC.2.5.1053-1060.2003

Naglik J, Albrecht A, Bader O, Hube B (2004) Candida albicans proteinases and host/pathogen interactions. Cell Microbiol 6:915–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00439.x

Fan Y, He H, Dong Y, Pan H (2013) Hyphae-specific genes HGC1, ALS3, HWP1, and ECE1 and relevant signaling pathways in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia 176:329–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-013-9684-6

Allert S, Förster TM, Svensson C-M et al (2018) Candida albicans-induced epithelial damage mediates translocation through intestinal barriers. MBio 9:e00915-e918. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00915-18

Maskow T, Paufler S (2015) What does calorimetry and thermodynamics of living cells tell us? Methods 76:3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.10.035

Braissant O, Wirz D, Göpfert B, Daniels AU (2010) Use of isothermal microcalorimetry to monitor microbial activities. FEMS Microbiol Lett 303:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01819.x

Krüger W, Vielreicher S, Kapitan M et al (2019) Fungal-bacterial interactions in health and disease. Pathogens 8:70. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8020070

Peters BM, Noverr MC (2013) Candida albicans-Staphylococcus aureus polymicrobial peritonitis modulates host innate immunity. Infect Immun 81:2178–2189. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00265-13

Klaerner HG, Uknis ME, Acton RD et al (1997) Candida albicans and Escherichia coli are synergistic pathogens during experimental microbial peritonitis. J Surg Res 70:161–165. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsre.1997.5110

Valentine M, Benadé E, Mouton M et al (2019) Binary interactions between the yeast Candida albicans and two gut-associated Bacteroides species. Microb Pathog 135:103619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103619

Lima WG, Campos ABC, Brito JCM et al (2022) Study of the influence of fecal material on the prognosis of intra-abdominal candidiasis using a murine model of technetium-99 m (99 mTc)-Candida albicans. Microbiol Res 263:127132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2022.127132

Cheng S, Clancy CJ, Xu W et al (2013) Profiling of Candida albicans gene expression during intra-abdominal candidiasis identifies biologic processes involved in pathogenesis. J Infect Dis 208:1529–1537. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit335

Vintrych P, Al-Obeidallah M, Horák J et al (2022) Modeling sepsis, with a special focus on large animal models of porcine peritonitis and bacteremia. Front Physiol 13:1094199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.1094199

Tariq T, Irfan FB, Farishta M et al (2019) Spontaneous fungal peritonitis: micro-organisms, management and mortality in liver cirrhosis-a systematic review. World J Hepatol 11:596–606. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i7.596

Maraolo AE, Buonomo AR, Zappulo E et al (2019) Unsolved issues in the treatment of spontaneous peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: nosocomial versus community-acquired infections and the role of fungi. Rev Recent Clin Trials 14:129–135. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574887114666181204102516

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Pr Dalle Frederic, from Dijon University Hospital, and Dr Znaidi Sadri, from Paris Institut Pasteur, for their technical advice, and helping establish the method of the molecular experiments. The authors thank Ganna Oliynyck, from Symcel AB (Solna, Sweden), for her technical support during the calscreenerTM installation and help for setup and analysis. The authors thank all the staff of the laboratory “Stress, Immunité, Pathogènes”, for their advice and help regarding laboratory experiments.

Funding

No specific grant was used. This work was supported by the department of Anaesthesiology, critical care and peri-operative medicine of the University Hospital of Nancy which allows the rental coast of the calScreener™ for a 6-month period. The experiments performed at the laboratory “Stress, Immunité, Pathogènes” were made by EN (PhD graduant) and ME (Master 2) and required no additional specific material or equipment than those already available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. ME: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. JB: investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing. AG: investigation, data curation. MRL: formal analysis, writing—review and editing. MM: conceptualization, methodology, supervision. PG: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was classified as non-interventional, hence only patient or substitute decision-makers’ “decline to participate” was requested. The study received approval from the local ethics committee of Nancy (Number 234).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests regarding the present work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Provides the qPCR protocol for the expression of C. albicans virulence gene with details regarding each genes (TableS1), the bacterial composition and macroscopic examination of the peritoneal fluids 11 to 26 (Table S2), the cytology, protein and glucose concentrations of included PF 1 to 10 and AF 1 to 5 (Table S3), additional metabolic parameters depending on the peritoneal fluid (24 to 26) and the presence of bacteria (Table S4), enlarged photo from the phenotypic approach (Figure S1), and the heat production profile of C. albicans combined with different bacteria in different peritoneal fluids (Figure S2).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Novy, E., Esposito, M., Birckener, J. et al. Reappraisal of intra-abdominal candidiasis: insights from peritoneal fluid analysis. ICMx 11, 67 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-023-00552-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-023-00552-0