Abstract

In critically ill patients, organ dysfunctions are routinely assessed, monitored, and treated. Mounting data show that substantial critical illness-induced changes in the immune system can be observed in most ICU patients and that not only “hyper-inflammation” but also persistence of an anti-inflammatory phenotype (as in sepsis-associated immunosuppression) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Despite common perception, changes in functional immunity cannot be adequately assessed by routine inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, or numerical analysis of leukocyte (sub)-counts. Cytokines appear also not suited due to their short half-life and pleiotropy, their unexclusive origin from immune cells, and their potential to undergo antagonization by circulating inactivating molecules. Thus, beyond leukocyte quantification and use of routine biomarkers, direct assessment of immune cell function seems required to characterize the immune systems’ status. This may include determination of, e.g., ex vivo cellular cytokine release, phagocytosis activity, and/or antigen-presenting capacity. In this regard, standardized flow-cytometric assessment of the major histocompatibility-II complex human leukocyte antigen (-D related) (HLA-DR) has gained particular interest. Monocytic HLA-DR (mHLA-DR) controls the interplay between innate and adaptive immunity and may serve as a “global” biomarker of injury-associated immunosuppression, and its decreased expression is associated with adverse clinical outcomes (e.g., secondary infection risk, mortality). Importantly, recent data demonstrate that injury-associated immunosuppression can be reversed—opening up new therapeutic avenues in affected patients. Here we discuss the potential scientific and clinical value of assessment of functional immunity with a focus on monocytes/macrophages and review the current state of knowledge and potential perspectives for affected critically ill patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

The immune system is an essential organ in higher life forms, and its dysfunction or “failure” may be life-threatening. In humans, the immune system is ubiquitously distributed within all organs and consists of humoral and cellular components organized in highly complex dynamic social network architecture-like structures [1]. Key functions of the immune system embrace injury control in inflammation/infection and tumor recognition/surveillance [1]. Despite its paramount importance, however, the immune system or “immune organ” is mostly overlooked on intensive care units (ICU) today [2,3,4,5,6,7]. This may at least partly be due to the fact that its functional status cannot be adequately assessed by use of routine biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, or numerical distribution of leukocyte (sub)-sets. Nevertheless, numerical assessment of leukocyte (sub-)populations may provide important additional information, e.g., when considerably deranged [8,9,10].

The typical initial immune system response to critical illness consists of systemic and local release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines and activation of specific immune and other cells. This may lead to distinct phenotype changes in immune cells [4, 6, 11, 12]. The traditional understanding was that uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., interleukin (IL)-1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α) would determine adverse clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock [4, 11]. Consequently, anti-inflammatory such as anti-TNF-α or anti-lipopolysaccharide (LPS) strategies were then tested in large-scale clinical trials. However, respective trial results returned negative or indicated increased intervention-related mortality. This highlighted that an anti-inflammatory approach would not provide general benefits for larger populations of patients with sepsis/septic shock [2,3,4,5, 7, 12]. Thereafter, immune status characterization in larger patient cohorts using novel biomarkers allowed for a more profound understanding. When looking at an individuals’ immune response, a high inter-individual variance and highly dynamic changes can be observed over time (Figs. 1 and 2) [4]. Today, it is well established that many critically ill patients either show signs of co-existing inflammatory and counter-regulatory anti-inflammatory response early in critical illness [13, 14] or will undergo transition from early pro- to later anti-inflammatory phenotypes (Fig. 2) [2, 4, 7, 11, 12]. The “net effect” (i.e., the resulting phenotype) of such profound anti-inflammation was referred to as “sepsis- (or injury-) associated immunosuppression (SAI/IAI)” and embraces diminished release of pro-inflammatory mediators, reduced phagocytosis, and reduced expression of cellular surface receptors involved in antigen-presenting activity (e.g., major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II) (Fig. 3) [4, 7, 11, 12]. This may be associated with enhanced immunological tolerance, increased immune cell apoptosis, and altered gene expression profiles [6, 11]. Interestingly, recent data show that respective changes are not exclusive to circulating immune cells and that comparable anti-inflammatory phenotypes can be found, e.g., in splenic or lung tissue and other solid organs [11].

Injury-associated immunosuppression in critically ill patients. Injury-associated immunosuppression (IAI) may develop in critical illness. IAI was shown to be of importance in cases of persistence for ≥ 2 days. Key future potential therapeutical options are listed. Monocytic HLA-DR expression (mHLA-DR, given in bound antibodies per cell) may serve as a global marker of IAI

Inter-individual injury-associated response patterns in critically ill patients. Patients with critical illness respond differently to injury (e.g., sepsis). Whereas patient “A” undergoes a pronounced inflammatory phase (net effects are shown) with regain of immunological homeostasis and subsequent survival, patient “B” enters a persisting phase of injury-associated immunosuppression (IAI). In IAI, viral reactivation rates, secondary (re-) infection rates, and mortality is increased. This underlines the importance of inter-individual response patterns and need for individual patient characterization before application of interventional therapeutic approaches (adapted from Hotchkiss et al., 2013 [4])

Infection-induced activation of key immune cells. In sepsis, bacterial infections trigger numerous pathways resulting in activation of key antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (i.e., monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells). Activated APCs predominantly express pro-inflammatory cytokines and present antigens bound to major histocompatibility (MHC) class II complexes (such as HLA-DR). Antigen-bound HLA-DR triggers T-cell-receptor (TCR) and co-stimulatory molecule (e.g. CD 40-CD40L) binding. Adaptive immune responses are initiated resulting in clearance of infection. In, e.g., cases of overwhelming infection, deactivation of monocytes, as in sepsis-associated immunosuppression (SAI), may occur. SAI is characterized by a shift towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype with predominant expression of IL-10 and diminished HLA-DR expression, resulting in impaired clearance of infection and increased mortality. In IAI, the deactivated phenotype can be observed immediately after injury

From a clinical perspective, it seems pivotal to distinguish temporary from persisting immunosuppression (Figs. 2 and 3). Data show that patients failing to recover from injury- (or sepsis-) associated immunosuppression are at increased risk for (secondary) infections or non-survival [4, 6, 11, 15] (Fig. 2). This affects patients with post cardio-surgical conditions [16], trauma [17], burns [18], pancreatitis [19, 20], solid organ transplantation [21], hepatic [22] or renal injury [23], stroke [24], myocardial infarction/heart failure, and cardiac arrest [25,26,27,28], as well as sepsis [15]. Recent technological advances now allow for better recognition/monitoring of SAI/IAI—thus opening up new avenues for the recognition, monitoring, and treatment of such functional immune “organ failure” [7].

Immunological markers in critical illness

For identification of patients at risk for SAI/IAI and associated complications, it seems important to briefly summarize key immunologic responses to injury (Fig. 3). The first response to injury or infection typically consists in local activation of humoral factors (e.g., complement factors) followed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are at the innate-adaptive interface (i.e., monocytes/macrophages or dendritic cells) [6, 29]. When activated, APCs release cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6) and other mediators that attract and activate even more APCs and neutrophils, enhance phagocytosis, and stimulate adaptive immune cells after migration to draining lymph nodes (e.g., antigen-loaded dendritic cells) [6, 29]. Following phagocytosis, APC-derived antigen presentation occurs via upregulation of class II transactivator (CIITA) and re-localization of MHC class II molecules from intracellular storages [29, 30]. Enhanced surface expression of antigen-loaded human leukocyte antigen (-D related) (HLA-DR; a key MHC class II molecule) on monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells then induces a T cell response via binding to T cell receptors (TCR) and co-stimulatory molecules (e.g., CD86-CD28 and CD40-CD40L) (Fig. 3). Over time, a “counter-regulatory” response may occur in monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells with increased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) [31, 32]. As a consequence, monocyte and dendritic cell deactivation with diminished expression of both HLA-DR and co-stimulatory molecules can be observed as an indicator of reduced phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and diminished induction of adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), an immature population of myeloid cells with immunosuppressive functions first described in cancer, was also demonstrated in patients with sepsis [33, 34]. Very recently, MDSC were shown associated with prolonged immunosuppression, in particular with diminished T cell functions and development of nosocomial infections in patients with sepsis [35, 36]. In addition, critically ill patients commonly show marked apoptosis-induced lymphopenia and impaired lymphocyte function which contribute to sepsis- and injury-associated immunosuppression as recently reviewed elsewhere [37].

Key cytokines: serum levels of IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α

Serum cytokine levels are routinely assessed in some institutions for earlier recognition, estimation of prognosis, and (intra-individual) follow-up of critically ill patients. However, it should be noted that they do not reflect immune cell functionality as cytokines are mostly pleiotropic, derived from different cells including non-immune cells, may be counteracted by natural inhibitors (e.g., gp130 for IL-6), and have variable clearance rates [4, 6, 11, 12]. In the following, we discuss three cytokines with pathophysiologic and/or diagnostic relevance in critical illness:

IL-6 is a potent pleiotropic cytokine with mainly pro-inflammatory effector function. IL-6 is expressed by monocytes/macrophages, endothelial lineage cells, and fibroblasts and augments immune responses via induction of T cell activation, B cell proliferation and differentiation, and stimulates acute phase protein release (e.g. C-reactive protein) [38]. Systemic IL-6 is detected rapidly with peak serum levels observed after about 2 h after an inflammatory insult [38]. IL-6 is usually assessed via automated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in specialized laboratories or via point-of-care tests (blood, liquor) [39, 40]. Owing to its fast induction and short half-life, serial IL-6 assessment may provide timely monitoring of an inflammatory burden when, e.g., compared to serial C-reactive protein measurements. Although increased IL-6 levels indicate adverse clinical outcomes in adults with sepsis/septic shock [38], implementing of IL-6 measurement in routine diagnostic work up was not shown to improve patient-centered clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, IL-6 was shown useful for sepsis diagnostics in neonatal/pediatric critically ill patients [41].

IL-10 is regarded the most prominent and exemplary anti-inflammatory cytokine. Comparable to IL-6, IL-10 is mainly expressed by monocytes/macrophages, has a short half-life, and can be assessed by ELISA. IL-10 was evaluated in several studies and functionally linked to the “classical” biphasic response model to severe injury [42, 43]. In contrast to IL-6, increased IL-10 expression induces antigen tolerance, enhances SAI, and increases susceptibility to infection, and IL-10 blockade reverses endotoxin tolerance in several preclinical studies, and some reports show a predictive value of IL-10 for mortality and/or (secondary) infection [42, 43].

TNF-α is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine predominantly released by monocytes/macrophages in early sepsis. It auto-stimulates effector functions and enhances the initiation of adaptive immune responses [44]. Several studies showed that elevated TNF-α levels are associated with increased mortality. When compared to other systemic inflammatory markers, it appears that TNF-α has lower discriminatory power with respect to outcome prediction [43, 45].

Functional markers: ex vivo TNF-α release

Ex vivo LPS-induced TNF-α production (e.g., after 4 h of stimulation) in whole blood allows for quantification of production/release of monocytes and dendritic cell-derived TNF-α. Diminished ex vivo TNF-α release is a key feature of immunosuppression in critically ill patients [4, 12, 46]. Nevertheless, ex vivo TNF-α release may not be a suitable diagnostic marker for cellular immune function as it requires standardized protocols for sample handling and specific stimulation conditions [46]. Today, no generally accepted standardized protocol for assessment of ex vivo TNF-α release exists, hindering multicenter studies [46]. Recently, whole-blood monocytic intracellular TNF-α assessment by flow cytometry was tested and showed promising results with regard to improved test feasibility [47].

Functional markers: phagocytosis assays

Phagocytosis involves recognition and engulfment with subsequent clearance of pathogens [48]. Numerous predominantly innate immune cells perform phagocytosis (e.g., neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells) [48]. Diminished phagocytic capability was linked to increased susceptibility for (secondary) infection in rodent models whereas in humans, the direct influence of critical illness on phagocytosis is incompletely understood [49]. Phagocytosis of neutrophils may be conserved in patients with sepsis, while in parallel, other neutrophil functions including chemotaxis and/or generation of oxidative burst may be impaired [49]. In general, phagocytosis assays are heterogeneous with varying specificity. Standardized laboratory protocols are missing, resulting in high intra- and inter-lab variation. Thus, phagocytosis assays may be of limited use for assessment of immune function in both clinical routine and multicenter clinical trials testing immunological interventions.

Functional markers: mHLA-DR expression

HLA-DR is a MHC class II molecule and predominantly expressed on monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells [29]. Its surface expression is indispensable for antigen presentation [29]. While increased HLA-DR expression reflects activation of immune cells, diminished expression thereof exhibits a phenotype with downregulation of antigen-presenting capacity and a shift from pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokine production [4, 12]. Surface expression of HLA-DR on monocytes/macrophages is crucial for initiation of adaptive immune responses [11, 29]. This signal is paralleled and/or augmented by activation of co-stimulatory molecules (e.g., CD40- CD40-ligand binding) (Fig. 3). Given the importance of monocytic HLA-DR (mHLA-DR) expression in respect to induction of adaptive immune responses, the key interplay of monocytes and dendritic cells with T cells was colloquially referred to as “immunological synapsis.” Assessment of mHLA-DR expression was thus proposed to serve as a “global” functional marker of immune function [4, 5, 7, 12]. In fact, the significance of mHLA-DR expression was first described about 30 years ago in patients undergoing organ transplantation when patients with low HLA-DR expression could be weaned from iatrogenic immunosuppression without transplant rejection [50].

Flow-cytometric assessment of mHLA-DR expression

Monocytic HLA-DR expression is performed via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from EDTA samples [51, 52]. FACS allows for simultaneous enumeration and assessment of several surface and intracellular antigens on specific immune cell subsets following staining with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies (Fig. 4). In 2005, the Quantibrite™ HLA-DR assay was demonstrated as the first standardized method for flow-cytometric mHLA-DR assessment with low inter-laboratory variability (coefficient of variation (CV) 15%, inter-laboratory CV < 4%) enabling comparison of data sets collected in multicenter studies [51]. Previous methods reporting percentages of HLA-DR positive cells (%HLA-DR) or mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) lacked an internationally accepted analytical standard and precluded between-center comparison of results [51]. In contrast, the Quantibrite™-HLA-DR assay harnesses calibration beads and a specifically formulated antibody-fluorochrome conjugate which allows the measurement of bound HLA-DR antibodies per cell (mAb/cell) independently from the combination of flow cytometer or instrument settings used in different laboratories [51]. Despite recent progress in standardization, flow cytometry still requires specialized lab equipment and staff, standardized analytical protocols, and timely handling of samples (maximum of 4–6 h in standard EDTA-tubes at room temperature for mHLA-DR) [51]. Delayed assessment of samples may induce activation of monocytes resulting in artificially increased mHLA-DR expression. Storage of EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood on ice or in a refrigerator or use of cell preservative containing tubes such as Cyto-Chex®-BCT increase analytic stability for mHLA-DR ([51] and Meisel et al., unpublished data). However, Cyto-Chex®-BCT tubes are expensive and not commonly available. Stained and fixed samples can be stored for at least 52 h before analysis [51]. Thus, mHLA-DR assessment as a biomarker for immune function usually requires establishing of the method in nearby hospital laboratories [7, 52]. In addition, blood samples are usually processed during standard laboratory opening hours and not 24/7 [51, 52]. Recently, an automated table cytometer was investigated as potential point-of-care tool for bedside mHLA-DR assessment which may be an important step to improve the availability of immune monitoring tools for ICU clinicians [53]. Further, quantification of HLA-DR expression and of other markers of innate and adaptive immune (dys)-regulation by real-time or digital PCR may help to overcome some of the above mentioned limitations of flow-cytometric mHLA-DR analysis and thus improve identification of patients with SAI/IAI [54,55,56,57]. However, the utility of theses assays needs further investigation.

Flow-cytometric assessment of monocytic HLA-DR expression. Upper row: after staining of EDTA samples with specific antibodies, HLA-DR expression is assessed on CD14+ monocytes by flow cytometry. Lower row: (left) Quantibrite™-PE beads are used to calculate a calibration curve (middle) for HLA-DR assessment on CD14+ monocytes. (Right) mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for HLA-DR on monocytes are converted in a given sample to molecules per cell using the calibration curve

Threshold levels

Using the earlier non-standardized method for mHLA-DR assessment as percent positive monocytes, most investigators (including our group) have established a cut-off at 30% HLA-DR-positive monocytes for severe injury-associated immunosuppression (earlier referred to as “immunoparalysis”) [51]. A recent comparison of the conventional method with the standardized quantitative assay for mHLA-DR (given in mAb/cell) performed by us revealed that the (earlier) cut-off value of 30% HLA-DR positive monocytes corresponds to about 5000 mAb/cell and 45% mHLA-DR to about 8000 mAb/cell [51]. The range between 30 and 45% HLA-DR positive monocytes was termed “borderline immunosuppression.” Thus, a cut-off value of 8000 mAb/cell may be used to indicate SAI/IAI and was used in subsequent interventional clinical trials [58]. Importantly, not single diminished values of mHLA-DR should be regarded as clinically relevant but rather the persistence of low mHLA-DR levels indicating failure for recovery [4, 7, 12, 15].

Monocytic HLA-DR expression in specific diseases

Sepsis/septic shock

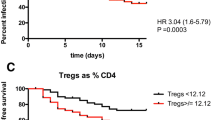

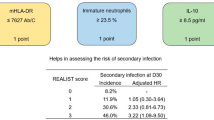

Sepsis is the clinical condition in which the mHLA-DR expression is best evaluated. Reduced mHLA-DR expression on admission [59, 60], days 1–3 [15, 45, 60] and days 6–8, [45, 59, 61] was significantly associated with increased mortality. Some studies show that the outcome-relevant difference in mHLA-DR expression is apparent only on days 3–4 (or later) with mHLA-DR returning to normal levels in survivors but not in non-survivors [15, 62]. Two further studies showed that the dynamic change (or recovery slope) in mHLA-DR expression between days 3 and 7 post injury is associated with mortality [15, 61, 62]. In one of these studies, it was shown that despite non-significant predictive value for single mHLA-DR values at time points 0, 3, and 7, the delta value between measurements days 0–3, 0–7, and 3–7 were highly predictive for mortality [62]. These results were confirmed in both adult [45] and pediatric patients [61]. One explanation for the better predictive value of relative changes in mHLA-DR expression than absolute values may be the high inter-individual variability of HLA-DR levels on monocytes. Monocytic HLA-DR expression on days 3–5 and 6–8 also independently predicts development of secondary infections [63]. Recovery of mHLA-DR may also reflect normalization of key metabolic pathways in sepsis [64,65,66], but further large-scale clinical data is needed.

Major surgery

Several studies assessed whether reduced mHLA-DR expression predicts adverse outcome following major surgical procedures. Culprits for post-surgical immune suppression may be surgical trauma, related intraoperative hypotension [67], and increased perioperative release of corticosteroids or catecholamines [68]. Moreover, anesthetic drugs such as fentanyl [69] may contribute to injury-associated immunosuppression (IAI). In patients with cardiovascular surgery, use of extracorporeal circuits is typically associated with a substantial pro-inflammatory response [16]. Cardiopulmonary bypass may be followed by IAI reflected by impaired monocytic ex vivo LPS-induced cytokine release and decreased mHLA-DR [16, 70, 71]. The nadir of mHLA-DR was typically observed on postoperative days 1–3, but diminished mHLA-DR expression was shown to persist up to postoperative day 10 in a considerable number of patients [70, 71]. In two larger studies investigating the predictive power of mHLA-DR on outcome in pediatric and adult patients post-cardiac surgery, reduced mHLA-DR expression on postoperative day 3 was associated with increased length of ICU stay/mechanical ventilation and development of postoperative sepsis [71, 72] after adjustment for bypass time, cross clamp time, complexity of surgical procedure, and a pediatric mortality risk score [72]. In adults, mHLA-DR expression on postoperative days 1–5 was significantly different between patients who later developed sepsis vs. with an uncomplicated course and was a factor with a high discriminatory power to identify patients with infection post cardiac surgery [16]. In patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, mHLA-DR expression after surgery was significantly associated with mortality although this was not related to increased postoperative infection rates [73].

Multiple trauma

Diminished mHLA-DR expression was observed in many patients with multiple trauma [17, 74]. In a prospective observational trial in 105 severely injured patients (injury severity score, ISS > 25), rise in mHLA-DR until days 3–4 following trauma, and not at any earlier day, was associated with non-development of severe infection/sepsis after adjusting for confounders [17]. The dynamic effect of mHLA-DR recovery was also shown in patients with multiple trauma and ISS > 9 [75]. Further studies report an association between mHLA-DR expression and occurrence of post-trauma sepsis as early as day 2 [75]. Monocytic HLA-DR expression was also associated with increased intrapulmonary shunting after severe trauma which is associated with increased incidence of pulmonary sepsis and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [75].

Central nervous system (CNS) injury

Infection is a common complication in patients after acute CNS injury. In particular, pneumonia is associated with worse neurological outcome and remains a leading cause of death. Experimental studies demonstrate that CNS injury-induced suppression of cellular and humoral immune functions contribute to the high incidence of infections [24]. Several clinical studies demonstrated reduced mHLA-DR expression in patients after cerebral ischemia, subarachnoid hemorrhage, spinal cord injury, or neurosurgery [76,77,78]. Importantly, CNS-injured patients with subsequent infectious complications showed lower mHLA-DR levels than those with an uncomplicated clinical course as early as day 1 after the insult and well before onset of infection [76,77,78] indicating that impaired host responses contribute to an increased infection risk after CNS injury. Very recently, we confirmed in a large prospective multicenter study stroke-induced immunosuppression (as indicated by low mHLA-DR expression) as an independent risk factor for the development of pneumonia besides the known neurological risk factors leading, e.g., to dysphagia and higher risk of aspiration [77].

Burn injury

Only few data are available in burn patients. One study in patients with severe burn injury (> 30% of body surface) indicates that days 2–3 mHLA-DR expression is significantly associated with increased mortality [18]. Patients who later developed sepsis had significantly lower mHLA-DR expression in the two ensuing days [18].

Pancreatitis

Reduced mHLA-DR expression is associated with increased disease severity in patients with severe pancreatitis [19, 20]. Suppression of mHLA-DR or decreased mHLA-DR is associated with development of sepsis [19, 20]. After day 3, failure to recover in mHLA-DR expression was associated with decreased survival [19].

Transplantation

The utility of mHLA-DR assessment in patients post (e.g., renal) transplantation was investigated more than 25 years ago. Increased mHLA-DR expression was observed to be associated with an increased rate of transplant rejection [21, 79] and may serve to monitor iatrogenic immunosuppression [50]. Failure to recover to normal mHLA-DR levels after transplantation is associated with increased rates of late post-transplant pneumonia in pediatric populations [80]. In adults after liver transplantation, reduced mHLA-DR expression levels are associated with pneumonia [81] and cytomegaly virus (CMV) reactivation [82].

Cardiopulmonary arrest

Monocytic HLA-DR expression predicts outcome in patients after cardiac arrest (CA) [25]. In 55 patients after out-of-hospital CA from non-shockable rhythm, mHLA-DR levels were significantly decreased when compared to healthy controls [25]. In this study, non-survivors showed different mHLA-DR dynamics between days 0 to 1 and 1 to 3 when compared to survivors. Whereas the slope between days 0 and 1 was steeper in non-survivors, mHLA-DR expression continued to decrease from days 1 to 3 in non-survivors (increased after day 1 in survivors) [25].

Other clinical conditions incl acute kidney injury and acute hepatic failure

The predictive value of mHLA-DR on outcome of patients with acute kidney injury (AKI) was assessed in one study [23]. Despite decreased mHLA-DR expression in AKI patients when compared to controls, the study did not identify a predictive value for mortality [23]. Few studies investigated mHLA-DR expression in patients with acute or decompensated chronic liver disease [22, 83]. Respective studies found a significant association between mHLA-DR expression and mortality at admission with an increase in predictive value when dynamic changes over time were investigated [83]. The discriminatory power of mHLA-DR for prediction of mortality was either similar [83] or lower than for the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score [22].

Injury-associated immunosuppression: reversal by therapeutic interventions

In the light of the potential of mHLA-DR for immune monitoring, several interventional biomarker-guided therapeutic strategies were tested in clinical trials. Respective approaches included extracorporeal removal of inhibiting factors via selective immunoadsorption [84], immunostimulation using interferon gamma (IFN-γ) [32] or stimulation with granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [58, 85, 86]. Potential additional approaches embrace interleukin 7 (IL-7) or anti-PD ligand 1 molecules (anti PD-L1). Future potential immunomodulatory approaches in sepsis are given in Fig. 5.

Potential future immunomodulatory approaches in sepsis. Key approaches to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression include cytokine-induced stimulation of monocyte/macrophage function (GM-CSF, IFN-γ), administration of survival factors for T cells (IL-7), blockade of anti-inflammatory mechanisms (anti-IL-10 antibody/antagonization of regulatory T-cell function), approaches to target immune cell exhaustion/apoptosis (anti-programmed death (PD) receptor 1 or PD-ligand1 (PD-L1)), and blockade of negative co-stimulators (e.g., cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 [CTLA-4] or B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA))

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ)

Stimulation of IFN-γ receptors, which are ubiquitously expressed, results in activation of numerous pro-inflammatory pathways. In a landmark trial, Doecke et al. showed that IFN-γ immunostimulation restores mHLA-DR expression in patients with sepsis-associated immunosuppression (SAI) [32]. Clearance of infection may be enhanced by IFN-γ use in adult patients with invasive fungal sepsis [87], and in a randomized double-blind clinical trial in trauma, a decreased incidence for ventilator-associated pneumonia was observed in patients with mHLA-DR < 30% receiving inhaled IFN-γ [74]. IFN-γ treatment was shown to reverse SAI resulting in higher TNF-α-, decreased IL-10, and increased mHLA-DR levels indicating reversal of the SAI phenotype [44]. Whether administration of IFN-γ in IAI results in lower mortality of affected patients remains unclear and larger investigations are needed but, importantly, major side effects of IFN-γ-induced immunostimulation were not observed [32, 74].

Granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)

In a randomized controlled double-blind placebo-controlled trial in 38 patients with sepsis, we could demonstrate reversal of persisting SAI following one treatment of subcutaneous GM-CSF [58]. In addition to reversal of SAI (as defined by mHLA-DR expression > 15,000 mAb/cell), we observed improvements in relevant patient-centered outcomes such as shortened time of mechanical ventilation [58]. The finding that GM-CSF reverses SAI is supported by other groups [86]. Whether clinical endpoints such as secondary infection rates are affected by therapeutical application of GM-CSF is under research (NCT02361528).However, smaller studies showed promising results with lower infection rates [88] or shorter duration of infection in immunosuppressed critically ill patients treated with GM-CSF. In another randomized-controlled trial in patients with sepsis and severe respiratory dysfunction, oxygenation significantly improved in patients receiving GM-CSF [89]. In newborns, we could recently demonstrate that reduced mHLA-DR expression may reflect immunological immaturity in very early newborns [90] and a meta-analysis on GM-CSF therapy indicated increased survival rates in very-low pre-term infants (< 2000 g) and infants with neutropenia when treated with GM-CSF [91]. Importantly, none of the clinical studies reported relevant side effects of GM-CSF treatment.

Conclusions

Critical illness may often induce persisting injury-associated immunosuppression with adverse effects on relevant patient-centered outcomes. However, despite the key task of ICU physicians to detect, monitor, and follow up on organ dysfunctions, functional failure of the “immune organ” seems currently mostly overlooked as it cannot be adequately assessed via use of routine biomarkers such as numerical distribution of leukocyte (sub)counts or systemic levels of soluble markers such as cytokines, procalcitonin, or acute phase proteins. Importantly, quantitative assessment of a given cell population does not per se allow to conclude on its functional status.

Today, flow-cytometric assessment of the mHLA-DR expression may serve as a standardized “global” biomarker to evaluate immune function. Persisting reduced mHLA-DR expression reflects a distinct immunological phenotype that is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, mHLA-DR assessment currently requires specialized laboratories that may not be available in all institutions. Following demonstration of immunological efficiency, biomarker-guided immunological interventions for injury-associated immunosuppression should now be performed in adequately characterized populations using relevant patient-centered clinical outcomes (e.g., mortality). We postulate that in the future of intensive care, personalized medicine that considers the individual immune functionality will be needed to significantly improve the outcome of affected patients.

Abbreviations

- APC:

-

Antigen-presenting cell

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- CIITA:

-

Class II transcriptor activator

- CMV:

-

Cytomegaly virus

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- EDTA:

-

Ethylene-diamin-tetra-acetat

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HLA(-DR):

-

Human leukocyte antigen (-D related)

- IAI:

-

Injury-associated immunosuppression

- IFN(-γ):

-

Interferon (gamma)

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MHC:

-

Major histocompatibility complex

- mHLA-DR:

-

Monocytic HLA-DR

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PD:

-

Programmed death

- SAI:

-

Sepsis-associated immunosuppression

- TNF (-α):

-

Tumor necrosis factor (alpha)

References

Rieckmann JC, Geiger R, Hornburg D, Wolf T, Kveler K, Jarrossay D, Sallusto F, Shen-Orr SS, Lanzavecchia A, Mann M et al (2017) Social network architecture of human immune cells unveiled by quantitative proteomics. Nat Immunol 18(5):583–593

Schefold JC, Hasper D, Reinke P, Monneret G, Volk HD (2008) Consider delayed immunosuppression into the concept of sepsis. Crit Care Med 36(11):3118

Carlet J, Cohen J, Calandra T, Opal SM, Masur H (2008) Sepsis: time to reconsider the concept. Crit Care Med 36(3):964–966

Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D (2013) Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis 13(3):260–268

Schefold JC, Hasper D, Volk HD, Reinke P (2008) Sepsis: time has come to focus on the later stages. Med Hypotheses 71(2):203–208

Venet F, Lukaszewicz AC, Payen D, Hotchkiss R, Monneret G (2013) Monitoring the immune response in sepsis: a rational approach to administration of immunoadjuvant therapies. Curr Opin Immunol 25(4):477–483

Schefold JC (2010) Measurement of monocytic HLA-DR (mHLA-DR) expression in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: assessment of immune organ failure. Intensive Care Med 36(11):1810–1812

Bermejo-Martin JF, Tamayo E, Ruiz G, Andaluz-Ojeda D, Herran-Monge R, Muriel-Bombin A, Fe Munoz M, Heredia-Rodriguez M, Citores R, Gomez-Herreras J et al (2014) Circulating neutrophil counts and mortality in septic shock. Crit Care 18(1):407

Hwang SY, Shin TG, Jo IJ, Jeon K, Suh GY, Lee TR, Yoon H, Cha WC, Sim MS (2017) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in critically-ill septic patients. Am J Emerg Med 35(2):234–239

Kim JW, Park JH, Kim DJ, Choi WH, Cheong JC, Kim JY (2017) The delta neutrophil index is a prognostic factor for postoperative mortality in patients with sepsis caused by peritonitis. PLoS One 12(8):e0182325

Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS et al (2011) Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA 306(23):2594–2605

Monneret G, Venet F, Pachot A, Lepape A (2008) Monitoring immune dysfunctions in the septic patient: a new skin for the old ceremony. Mol Med 14(1–2):64–78

Tamayo E, Fernandez A, Almansa R, Carrasco E, Heredia M, Lajo C, Goncalves L, Gomez-Herreras JI, de Lejarazu RO, Bermejo-Martin JF (2011) Pro- and anti-inflammatory responses are regulated simultaneously from the first moments of septic shock. Eur Cytokine Netw 22(2):82–87

Xiao W, Mindrinos MN, Seok J, Cuschieri J, Cuenca AG, Gao H, Hayden DL, Hennessy L, Moore EE, Minei JP et al (2011) A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med 208(13):2581–2590

Monneret G, Lepape A, Voirin N, Bohe J, Venet F, Debard AL, Thizy H, Bienvenu J, Gueyffier F, Vanhems P (2006) Persisting low monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression predicts mortality in septic shock. Intensive Care Med 32(8):1175–1183

Strohmeyer JC, Blume C, Meisel C, Doecke WD, Hummel M, Hoeflich C, Thiele K, Unbehaun A, Hetzer R, Volk HD (2003) Standardized immune monitoring for the prediction of infections after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in risk patients. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 53(1):54–62

Cheron A, Floccard B, Allaouchiche B, Guignant C, Poitevin F, Malcus C, Crozon J, Faure A, Guillaume C, Marcotte G et al (2010) Lack of recovery in monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression is independently associated with the development of sepsis after major trauma. Crit Care 14(6):R208

Venet F, Tissot S, Debard AL, Faudot C, Crampe C, Pachot A, Ayala A, Monneret G (2007) Decreased monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression after severe burn injury: correlation with severity and secondary septic shock. Crit Care Med 35(8):1910–1917

Ho YP, Sheen IS, Chiu CT, Wu CS, Lin CY (2006) A strong association between down-regulation of HLA-DR expression and the late mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 101(5):1117–1124

Satoh A, Miura T, Satoh K, Masamune A, Yamagiwa T, Sakai Y, Shibuya K, Takeda K, Kaku M, Shimosegawa T (2002) Human leukocyte antigen-DR expression on peripheral monocytes as a predictive marker of sepsis during acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 25(3):245–250

Reinke P, Fietze E, Docke WD, Kern F, Ewert R, Volk HD (1994) Late acute rejection in long-term renal allograft recipients. Diagnostic and predictive value of circulating activated T cells. Transplantation 58(1):35–41

Antoniades CG, Berry PA, Davies ET, Hussain M, Bernal W, Vergani D, Wendon J (2006) Reduced monocyte HLA-DR expression: a novel biomarker of disease severity and outcome in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology 44(1):34–43

Ahlstrom A, Hynninen M, Tallgren M, Kuusela P, Valtonen M, Orko R, Siitonen S, Takkunen O, Pettila V (2004) Predictive value of interleukins 6, 8 and 10, and low HLA-DR expression in acute renal failure. Clin Nephrol 61(2):103–110

Meisel A, Meisel C, Harms H, Hartmann O, Ulm L (2012) Predicting post-stroke infections and outcome with blood-based immune and stress markers. Cerebrovasc Dis 33(6):580–588

Venet F, Cour M, Demaret J, Monneret G, Argaud L (2016) Decreased monocyte HLA-DR expression in patients after non-shockable out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Shock 46(1):33–36

Haeusler KG, Schmidt WU, Foehring F, Meisel C, Guenther C, Brunecker P, Kunze C, Helms T, Dirnagl U, Volk HD et al (2012) Immune responses after acute ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 155(3):372–377

Schefold JC, Filippatos G, Hasenfuss G, Anker SD, von Haehling S (2016) Heart failure and kidney dysfunction: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Nephrol 12(10):610–623

von Haehling S, Schefold JC, Jankowska E, Doehner W, Springer J, Strohschein K, Genth-Zotz S, Volk HD, Poole-Wilson P, Anker SD (2009) Leukocyte redistribution: effects of beta blockers in patients with chronic heart failure. PLoS One. 29;4(7):e6411.

Roche PA, Furuta K (2015) The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nat Rev Immunol 15(4):203–216

Le Tulzo Y, Pangault C, Amiot L, Guilloux V, Tribut O, Arvieux C, Camus C, Fauchet R, Thomas R, Drenou B (2004) Monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR transcriptional downregulation by cortisol during septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169(10):1144–1151

Poehlmann H, Schefold JC, Zuckermann-Becker H, Volk HD, Meisel C (2009) Phenotype changes and impaired function of dendritic cell subsets in patients with sepsis: a prospective observational analysis. Crit Care 13(4):R119

Docke WD, Randow F, Syrbe U, Krausch D, Asadullah K, Reinke P, Volk HD, Kox W (1997) Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med 3(6):678–681

Darcy CJ, Minigo G, Piera KA, Davis JS, McNeil YR, Chen Y, Volkheimer AD, Weinberg JB, Anstey NM, Woodberry T (2014) Neutrophils with myeloid derived suppressor function deplete arginine and constrain T cell function in septic shock patients. Crit Care 18(4):R163

Janols H, Bergenfelz C, Allaoui R, Larsson AM, Ryden L, Bjornsson S, Janciauskiene S, Wullt M, Bredberg A, Leandersson K (2014) A high frequency of MDSCs in sepsis patients, with the granulocytic subtype dominating in gram-positive cases. J Leukoc Biol 96(5):685–693

Uhel F, Azzaoui I, Gregoire M, Pangault C, Dulong J, Tadie JM, Gacouin A, Camus C, Cynober L, Fest T et al (2017) Early expansion of circulating granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells predicts development of nosocomial infections in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196(3):315–327

Mathias B, Delmas AL, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Vanzant EL, Szpila BE, Mohr AM, Moore FA, Brakenridge SC, Brumback BA, Moldawer LL et al (2017) Human myeloid-derived suppressor cells are associated with chronic immune suppression after severe sepsis/septic shock. Ann Surg 265(4):827–834

Girardot T, Rimmele T, Venet F, Monneret G (2017) Apoptosis-induced lymphopenia in sepsis and other severe injuries. Apoptosis 22(2):295–305

Van Snick J (1990) Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol 8:253–278

Dengler J, Schefold JC, Graetz D, Meisel C, Splettstosser G, Volk HD, Schlosser HG (2008) Point-of-care testing for interleukin-6 in cerebro spinal fluid (CSF) after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Med Sci Monit 14(12):BR265–BR268

Schefold JC, Hasper D, von Haehling S, Meisel C, Reinke P, Schlosser HG (2008) Interleukin-6 serum level assessment using a new qualitative point-of-care test in sepsis: a comparison with ELISA measurements. Clin Biochem 41(10–11):893–898

Shahkar L, Keshtkar A, Mirfazeli A, Ahani A, Roshandel G (2011) The role of IL-6 for predicting neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Pediatr 21(4):411–417

Frencken JF, van Vught LA, Peelen LM, Ong DSY, Klein Klouwenberg PMC, Horn J, Bonten MJM, van der Poll T, Cremer OL (2017) An unbalanced inflammatory cytokine response is not associated with mortality following sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med 45(5):e493–e499

Monneret G, Finck ME, Venet F, Debard AL, Bohe J, Bienvenu J, Lepape A (2004) The anti-inflammatory response dominates after septic shock: association of low monocyte HLA-DR expression and high interleukin-10 concentration. Immunol Lett 95(2):193–198

Leentjens J, Kox M, Koch RM, Preijers F, Joosten LA, van der Hoeven JG, Netea MG, Pickkers P (2012) Reversal of immunoparalysis in humans in vivo: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186(9):838–845

Drewry AM, Ablordeppey EA, Murray ET, Beiter ER, Walton AH, Hall MW, Hotchkiss RS (2016) Comparison of monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression and stimulated tumor necrosis factor alpha production as outcome predictors in severe sepsis: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 20(1):334

Segre E, Fullerton JN (2016) Stimulated whole blood cytokine release as a biomarker of immunosuppression in the critically ill: the need for a standardized methodology. Shock 45(5):490–494

Monneret G, Demaret J, Gossez M, Reverdiau E, Malergue F, Rimmele T, Venet F (2017) Novel approach in monocyte intracellular TNF measurement: application to sepsis-induced immune alterations. Shock 47(3):318–322

Pauwels AM, Trost M, Beyaert R, Hoffmann E (2017) Patterns, receptors, and signals: regulation of Phagosome maturation. Trends Immunol

Demaret J, Venet F, Friggeri A, Cazalis MA, Plassais J, Jallades L, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, Textoris J, Lepape A et al (2015) Marked alterations of neutrophil functions during sepsis-induced immunosuppression. J Leukoc Biol 98(6):1081–1090

Reinke P, Volk HD (1992) Diagnostic and predictive value of an immune monitoring program for complications after kidney transplantation. Urol Int 49(2):69–75

Docke WD, Hoflich C, Davis KA, Rottgers K, Meisel C, Kiefer P, Weber SU, Hedwig-Geissing M, Kreuzfelder E, Tschentscher P et al (2005) Monitoring temporary immunodepression by flow cytometric measurement of monocytic HLA-DR expression: a multicenter standardized study. Clin Chem 51(12):2341–2347

Monneret G, Venet F, Meisel C, Schefold JC (2010) Assessment of monocytic HLA-DR expression in ICU patients: analytical issues for multicentric flow cytometry studies. Crit Care 14(4):432

Zouiouich M, Gossez M, Venet F, Rimmele T, Monneret G (2017) Automated bedside flow cytometer for mHLA-DR expression measurement: a comparison study with reference protocol. Intensive Care Med Exp 5(1):39

Cajander S, Backman A, Tina E, Stralin K, Soderquist B, Kallman J (2013) Preliminary results in quantitation of HLA-DRA by real-time PCR: a promising approach to identify immunosuppression in sepsis. Crit Care 17(5):R223

Almansa R, Ortega A, Avila-Alonso A, Heredia-Rodriguez M, Martin S, Benavides D, Martin-Fernandez M, Rico L, Aldecoa C, Rico J et al (2017) Quantification of immune dysregulation by next-generation polymerase chain reaction to improve sepsis diagnosis in surgical patients. Ann Surg

Cajander S, Tina E, Backman A, Magnuson A, Stralin K, Soderquist B, Kallman J (2016) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction measurement of HLA-DRA gene expression in whole blood is highly reproducible and shows changes that reflect dynamic shifts in monocyte surface HLA-DR expression during the course of sepsis. PLoS One 11(5):e0154690

Winkler MS, Rissiek A, Priefler M, Schwedhelm E, Robbe L, Bauer A, Zahrte C, Zoellner C, Kluge S, Nierhaus A (2017) Human leucocyte antigen (HLA-DR) gene expression is reduced in sepsis and correlates with impaired TNFalpha response: a diagnostic tool for immunosuppression? PLoS One 12(8):e0182427

Meisel C, Schefold JC, Pschowski R, Baumann T, Hetzger K, Gregor J, Weber-Carstens S, Hasper D, Keh D, Zuckermann H et al (2009) Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180(7):640–648

Lekkou A, Karakantza M, Mouzaki A, Kalfarentzos F, Gogos CA (2004) Cytokine production and monocyte HLA-DR expression as predictors of outcome for patients with community-acquired severe infections. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11(1):161–167

Lukaszewicz AC, Grienay M, Resche-Rigon M, Pirracchio R, Faivre V, Boval B, Payen D (2009) Monocytic HLA-DR expression in intensive care patients: interest for prognosis and secondary infection prediction. Crit Care Med 37(10):2746–2752

Manzoli TF, Troster EJ, Ferranti JF, Sales MM (2016) Prolonged suppression of monocytic human leukocyte antigen-DR expression correlates with mortality in pediatric septic patients in a pediatric tertiary intensive care unit. J Crit Care 33:84–89

Wu JF, Ma J, Chen J, Ou-Yang B, Chen MY, Li LF, Liu YJ, Lin AH, Guan XD (2011) Changes of monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression as a reliable predictor of mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care 15(5):R220

Landelle C, Lepape A, Voirin N, Tognet E, Venet F, Bohe J, Vanhems P, Monneret G (2010) Low monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR is independently associated with nosocomial infections after septic shock. Intensive Care Med 36(11):1859–1866

Schefold JC, Zeden JP, Pschowski R, Hammoud B, Fotopoulou C, Hasper D, Fusch G, Von Haehling S, Volk HD, Meisel C et al (2010) Treatment with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is associated with reduced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity and kynurenine pathway catabolites in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Scand J Infect Dis 42(3):164–171

Zeden JP, Fusch G, Holtfreter B, Schefold JC, Reinke P, Domanska G, Haas JP, Gruendling M, Westerholt A, Schuett C (2010) Excessive tryptophan catabolism along the kynurenine pathway precedes ongoing sepsis in critically ill patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 38(2):307–316

Groebner AE, Schulke K, Schefold JC, Fusch G, Sinowatz F, Reichenbach HD, Wolf E, Meyer HH, Ulbrich SE (2011) Immunological mechanisms to establish embryo tolerance in early bovine pregnancy. Reprod Fertil Dev 23(5):619–632

Ayala A, Perrin MM, Chaudry IH (1990) Defective macrophage antigen presentation following haemorrhage is associated with the loss of MHC class II (Ia) antigens. Immunology 70(1):33–39

Asadullah K, Woiciechowsky C, Docke WD, Liebenthal C, Wauer H, Kox W, Volk HD, Vogel S, Von Baehr R (1995) Immunodepression following neurosurgical procedures. Crit Care Med 23(12):1976–1983

Carrera J, Catala JC, Monedero P, Carrascosa F, Arroyo JL, Subira ML (1992) Depression of the mononuclear phagocyte system caused by high doses of narcotics. Rev Med Univ Navarra 37(3):119–125

Borgermann J, Friedrich I, Scheubel R, Kuss O, Lendemans S, Silber RE, Kreuzfelder E, Flohe S (2007) Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) restores decreased monocyte HLA-DR expression after cardiopulmonary bypass. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 55(1):24–31

Franke A, Lante W, Zoeller LG, Kurig E, Weinhold C, Markewitz A (2008) Delayed recovery of human leukocyte antigen-DR expression after cardiac surgery with early non-lethal postoperative complications: only an epiphenomenon? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 7(2):207–211

Allen ML, Peters MJ, Goldman A, Elliott M, James I, Callard R, Klein NJ (2002) Early postoperative monocyte deactivation predicts systemic inflammation and prolonged stay in pediatric cardiac intensive care. Crit Care Med 30(5):1140–1145

Haveman JW, van den Berg AP, Verhoeven EL, Nijsten MW, van den Dungen JJ, The HT, Zwaveling JH (2006) HLA-DR expression on monocytes and systemic inflammation in patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Crit Care 10(4):R119

Nakos G, Malamou-Mitsi VD, Lachana A, Karassavoglou A, Kitsiouli E, Agnandi N, Lekka ME (2002) Immunoparalysis in patients with severe trauma and the effect of inhaled interferon-gamma. Crit Care Med 30(7):1488–1494

Ditschkowski M, Kreuzfelder E, Rebmann V, Ferencik S, Majetschak M, Schmid EN, Obertacke U, Hirche H, Schade UF, Grosse-Wilde H (1999) HLA-DR expression and soluble HLA-DR levels in septic patients after trauma. Ann Surg 229(2):246–254

Harms H, Prass K, Meisel C, Klehmet J, Rogge W, Drenckhahn C, Gohler J, Bereswill S, Gobel U, Wernecke KD et al (2008) Preventive antibacterial therapy in acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 3(5):e2158

Hoffmann S, Harms H, Ulm L, Nabavi DG, Mackert BM, Schmehl I, Jungehulsing GJ, Montaner J, Bustamante A, Hermans M et al (2016) Stroke-induced immunodepression and dysphagia independently predict stroke-associated pneumonia—the PREDICT study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab:271678x16671964. doi:10.1177/0271678X16671964

Sarrafzadeh A, Schlenk F, Meisel A, Dreier J, Vajkoczy P, Meisel C (2011) Immunodepression after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 42(1):53–58

Henny FC, Weening JJ, Baldwin WM, Oljans PJ, Tanke HJ, van Es LA, Paul LC (1986) Expression of HLA-DR antigens on peripheral blood T lymphocytes and renal graft tubular epithelial cells in association with rejection. Transplantation 42(5):479–483

Hoffman JA, Weinberg KI, Azen CG, Horn MV, Dukes L, Starnes VA, Woo MS (2004) Human leukocyte antigen-DR expression on peripheral blood monocytes and the risk of pneumonia in pediatric lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 6(4):147–155

van den Berk JM, Oldenburger RH, van den Berg AP, Klompmaker IJ, Mesander G, van Son WJ, van der Bij W, Sloof MJ, The TH (1997) Low HLA-DR expression on monocytes as a prognostic marker for bacterial sepsis after liver transplantation. Transplantation 63(12):1846–1848

Besancon-Watelet C, De March AK, Renoult E, Kessler M, Bene MC, Faure GC, Sarda MN (2000) Early increase of peripheral B cell levels in kidney transplant recipients with CMV infection or reactivation. Transplantation 69(3):366–371

Berres ML, Schnyder B, Yagmur E, Inglis B, Stanzel S, Tischendorf JJ, Koch A, Winograd R, Trautwein C, Wasmuth HE (2009) Longitudinal monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression is a prognostic marker in critically ill patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Liver Int 29(4):536–543

Schefold JC, von Haehling S, Corsepius M, Pohle C, Kruschke P, Zuckermann H, Volk HD, Reinke P (2007) A novel selective extracorporeal intervention in sepsis: immunoadsorption of endotoxin, interleukin 6, and complement-activating product 5a. Shock 28(4):418–425

Schefold JC (2011) Immunostimulation using granulocyte- and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care 15(2):136

Nierhaus A, Montag B, Timmler N, Frings DP, Gutensohn K, Jung R, Schneider CG, Pothmann W, Brassel AK, Schulte Am Esch J (2003) Reversal of immunoparalysis by recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med 29(4):646–651

Delsing CE, Gresnigt MS, Leentjens J, Preijers F, Frager FA, Kox M, Monneret G, Venet F, Bleeker-Rovers CP, van de Veerdonk FL et al (2014) Interferon-gamma as adjunctive immunotherapy for invasive fungal infections: a case series. BMC Infect Dis 14:166

Hall MW, Knatz NL, Vetterly C, Tomarello S, Wewers MD, Volk HD, Carcillo JA (2011) Immunoparalysis and nosocomial infection in children with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med 37(3):525–532

Presneill JJ, Harris T, Stewart AG, Cade JF, Wilson JW (2002) A randomized phase II trial of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor therapy in severe sepsis with respiratory dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(2):138–143

Schefold JC, Porz L, Uebe B, Poehlmann H, von Haehling S, Jung A, Unterwalder N, Meisel C (2015) Diminished HLA-DR expression on monocyte and dendritic cell subsets indicating impairment of cellular immunity in pre-term neonates: a prospective observational analysis. J Perinat Med 43(5):609–618

Bernstein HM, Pollock BH, Calhoun DA, Christensen RD (2001) Administration of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to neonates with septicemia: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr 138(6):917–920

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (CAP, CM, MF, JCS) wrote the article and revised it for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pfortmueller, C.A., Meisel, C., Fux, M. et al. Assessment of immune organ dysfunction in critical illness: utility of innate immune response markers. ICMx 5, 49 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-017-0163-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-017-0163-0