Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify modifiable medical comorbidities, laboratory markers and flaws in perioperative management that increase the risk of acute dislocation in total hip arthroplasty (THA) patients.

Methods

All THA with primary indications of osteoarthritis from 2007 to 2020 were queried from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. Demographic data, preoperative laboratory values, recorded past medical history, operative details as well as outcome and complication information were collected. The study population was divided into two cohorts: non-dislocation and dislocation patients. Statistics were performed to compare the characteristics of both cohorts and to identify risk factors for prosthetic dislocation (α < 0.05).

Results

275,107 patients underwent primary THA in 2007 to 2020, of which 1,258 (0.5%) patients experienced a prosthetic hip dislocation. Demographics between non-dislocation and dislocation cohorts varied significantly in that dislocation patients were more likely to be female, older, with lower body mass index and a more extensive past medical history (all p < 0.05). Moreover, hypoalbuminemia and moderate/severe anemia were associated with increased risk of dislocation in a multivariate model (all p < 0.05). Finally, use of general anesthesia, longer operative time, and longer length of hospital stay correlated with greater risk of prosthetic dislocation (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Elderly female patients and patients with certain abnormal preoperative laboratory values are at risk for sustaining acute dislocations after index THA. Careful interdisciplinary planning and medical optimization should be considered in high-risk patients as dislocations significantly increase the risk of sepsis, cerebral vascular accident, and blood transfusions on readmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a common surgical procedure that has been considered one of the most cost-effective treatments for hip osteoarthritis by decreasing pain, improving mobility and function as measured by multiple patient-reported outcome scores. THA has provided long term improvement in patient quality of life with more than 95% survival rate of hip arthroplasties after 10 years [1]. While rare, one of the most common complications of THA is prosthetic hip dislocation which is the primary cause of readmission within 90 days after the surgery [2, 3].

Prosthetic hip dislocation is typically an early post-operative period complication with first-year dislocation rates ranging from 0.5 to 1.5% with some variation reported with different surgical approaches [4,5,6]. Several mechanisms have been proposed and are believed to contribute to the dislocating event which include the following: 1) mispositioning or loosening of the prosthesis, 2) contact between the neck of the prosthesis with the articular component, 3) contact between the bony femur and bony pelvis, and lastly, 4) hyperlaxity of the surrounding musculature or tissue [4,5,6].

Due to the unfavorable effect that hip dislocations have on patient satisfaction and surgical outcome, a strong effort has been dedicated to identifying risk factors which predispose patients to dislocations. Of note, this effort has resulted in the identification of several patient-associated factors including previous hip surgery, patient non-compliance, neuromuscular and cognitive disorders, smoking/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ASA class of 3 to 5, fracture, elevated creatinine (Cr), age ≥ 80 years, chronic steroid use, longer operative duration, and general anesthesia [7]. Additionally, several patient-associated risk factors have been shown to affect overall patient outcomes in THA, including frailty, age, malnourishment, and medical comorbidities (e.g., anemia, chronic kidney disease [CKD]) but a direct relationship with post-operative hip dislocation rate has either not been investigated or has not been consistently demonstrated across studies [8, 9]. For example, a previous study has concluded an increased risk of mortality and perioperative complications in primary and revision hip arthroplasty patients [10]. Similarly, a previous study by Eminovic et al. determined an increased hospital stay and post-operative complications in malnourished patients undergoing elective THA [11]. In both studies, no specific relationship was characterized with post-operative hip dislocations.

Understanding the several risk factors that increases a patient’s propensity for post-operative hip dislocation is crucial for patient candidacy, pre-operative planning, intra operative implementation, and post-operative precautions. For this reason, our investigation aims to utilize the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) which provides an extensive database with a large sample size to further identify other patient-related risk factors associated with prosthetic hip dislocation such as dehydration, malnourishment, frailty index, severity of anemia, and other patient-associated risk factors.

Methods

The NSQIP database was queried for all primary THA performed from 2007 to 2020. As the database was de-identified, this study was exempt from approval by the Institutional Review Board and thus informed consent was not obtained. The NSQIP database is a well-known and well-utilized resource. It has been used for many research studies related to general orthopedics, including hip arthroplasty [12,13,14,15]. The database contains patient information from greater than 600 hospitals across the United States (US). Data is obtained and uploaded by certified health care professionals using outpatient visits, direct interviews and reviews of postoperative medical record notes [16]. The inter-reliability disagreement for this data has been estimated to be < 2% [17]. Additionally, the database is audited at regular intervals helping to ensure its accuracy [18].

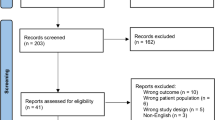

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27,130 was used to identify patients who underwent THA from 2007 to 2020. Patients aged ≥ 18 years with documented past medical history, preoperative laboratory values as well as reported outcomes and complications were included in this study. Patients younger than 18 years of age and those without outcome and complication data were excluded. 275,107 subjects met the inclusion criteria for the study and thus were included in statistical analysis. Demographic data, preoperative laboratory values, recorded past medical history, THA operative details as well as outcome and complication information were collected. As this study sought to evaluate the risk factors for prosthetic hip dislocation, the study population was divided into two cohorts: non-dislocation and dislocation patients. This was done using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth (996.4, 996.5, 996.6, 996.7) and Tenth Revisions (M24 and T84), Clinical Modification codes for prosthetic hip dislocation.

Laboratory values included sodium (normal 135 to 147 mmol/l), eGFR (normal ≥ 90 ml/min/1.73m2, mild/moderate 30 to 89 ml/min/1.73m2, severe < 30 ml/min/1.73m2), WBC (low/normal 0 to 11 × 109/l, high 12 + × 109/l), and platelets (low 0 to 139 × 10.9/l). Levels of anemia were stratified by hematocrit levels with nonanemia (hematocrit > 36% for women, > 39% for men), mild anemia (hematocrit 33%-36% for women, 33%-39% for men), and moderate to severe anemia (hematocrit < 33% for both women and men). The BUN/Cr ratio has been validated as a sensitive marker for predicting dehydration, and severity of dehydration was defined as Bun/Cr < 20 (non-dehydrated), 20 ≤ Bun/C ≤ 25 (moderately-dehydrated), 25 < Bun/Cr (severely-dehydrated). Hypoalbuminemia has been validated in the literature as a marker for malnutrition and is defined as levels < 35 g/l [13]. The 5-factor modified frailty index (mFI-5) has been previously validated in joint arthroplasty to correlate with increased morbidity and mortality [19]. The frailty score is a summation of presence of five comorbid variables, including congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or current pneumonia, hypertension requiring medication, and non-independent functional status [19].

Bivariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for prosthetic dislocation were performed. Comparative analyses were conducted using Chi-squared or Fischer’s exact test for categorical variables and student’s t-test for continuous variables. To evaluate the correlation between laboratory values and prosthetic dislocation, bivariate logistic regression analyses were performed. Multivariate analyses were then completed using stepwise logistic regression as well as clinical judgment to identify the best fit model for all demographic, preoperative laboratory values, past medical history and operative detail variables. Furthermore, additional multivariate stepwise logistic regression analyses were performed for medical complications to identify possible confounding variables for prosthetic dislocation. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05. Statistics were performed on IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Subject characteristics

This study included 275,107 patients who underwent primary THA between the years 2007 and 2020. Of these subjects, 1,258 (0.5%) experienced a postoperative prosthetic hip dislocation. A greater proportion of the dislocation patients were female (all patients: 55.0% female, dislocation patients: 59.7% female, p = 0.004) and Hispanic (all patients: 3.8% Hispanic, dislocation patients: 5.7% Hispanic, p = 0.001). The distribution of races and body mass index (BMI) categories varied significantly between non-dislocation and dislocation groups (all p < 0.05). On average, dislocation patients were older (all patients: 65.4 ± 11.4 years, dislocation patients: 68.1 ± 13.3 years, p < 0.001) with lower BMI (all patients: 30.2 ± 6.3 BMI, dislocation patients: 28.9 ± 6.8 BMI, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

With regards to preoperative laboratory values, the non-dislocation and dislocation groups had many differences. A greater percentage of dislocation patients had severe estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) levels (all patients: 0.8% severe eGFR, dislocation patients: 2.3% severe eGFR, p < 0.001) as well as low sodium levels (all patients: 4.8% hyponatremic, dislocation patients: 9.2% hyponatremic, p < 0.001). Moreover, dislocation patients had higher average blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (all patients: 17.9 ± 7.3 BUN, dislocation patients: 18.5 ± 8.6 BUN, p = 0.011), serum Cr (all patients: 0.9 ± 0.4 Cr, dislocation patients: 1.0 ± 0.6 Cr, p = 0.002) as well as international normalized ratio (INR) (all patients: 1.0 ± 0.3 INR, dislocation patients: 1.1 ± 0.3 INR, p < 0.001). A larger proportion of dislocation patients had a < 20 BUN/Cr level (all patients: 52.7%, dislocation patients: 51.1%) as well as a 25 + BUN/Cr level (all patients: 21.0%, dislocation patients: 24.0%) (p = 0.039). Similarly, subjects who experienced a prosthetic dislocation after primary THA had a greater distribution of patients who were hypoalbuminemic (all patients: 5.3% hypoalbuminemic, dislocation patients: 21.0% hypoalbuminemic, p < 0.001), with alkaline phosphatase levels 148 + (all patients: 2.6%, dislocation patients: 7.9%, p < 0.001), high white blood cell (WBC) count (all patients: 2.7% with leukocytosis, dislocation patients: 4.6% with leukocytosis, p < 0.001) and mild to severe anemia (all patients: 14.2% anemic, dislocation patients: 37.1% anemic, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

For subject past medical history, dislocation patients were more likely to be insulin dependent (all patients: 2.9% insulin dependent, dislocation patients: 5.6% insulin dependent) as well as non-insulin dependent diabetics (all patients: 9.1% non-insulin dependent, dislocation patients: 10.0% non-insulin dependent) (p < 0.001). Dislocation subjects had larger proportions of smokers (all patients: 12.5% smokers, dislocation patients: 15.0% smokers, p = 0.006), patients reporting dyspnea on moderate exertion (all patients: 4.5% with dyspnea, dislocation patients: 6.2% with dyspnea, p = 0.011) as well as patients with severe COPD, congestive heart failure (CHF), hypertension requiring medication and, finally, patients currently on dialysis (all p < 0.05). Additionally, a greater percentage of dislocation patients had lost > 10% of their body weight in the last 6 months (all patients: 0.2% with weight loss, dislocation patients: 0.9% with weight loss, p < 0.001), had a history of a bleeding disorder (all patients: 2.3% with a bleeding disorder, dislocation patients: 4.1% with a bleeding disorder, p < 0.001) and who required a transfusion of > 4 units of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) in the 72 h before surgery (all patients: 0.2% transfused, dislocation patients: 1.4% transfused). A significantly larger proportion of dislocation patients experienced some form of preoperative systemic sepsis (i.e., systemic inflammatory response syndrome [SIRS], sepsis, septic shock) prior to primary THA (all patients: 0.6% septic, 2.0% septic, p < 0.001). Using the mFI-5 clinical frailty scale, which is a validated measure used to quantify the degree of disability from geriatric frailty, more dislocation patients had a score of ≥ 2 (all patients: 13.7% frail, dislocation patients: 22.3% frail, p < 0.001), which indicates greater disability (Table 1).

With regards to operative details, a greater proportion of dislocation patients had inpatient surgery (all patients: 93.5% inpatient, dislocation patients: 97.3% inpatient, p < 0.001) under general anesthesia (all patients: 47.4% general anesthesia, dislocation patients: 69.2% general anesthesia, p < 0.001). More dislocation patients had an ASA class of > 2 (all patients: 44.6%, dislocation patients: 63.3%, p < 0.001) and had a longer average operative time (all patients: 91.9 ± 39.1 min, dislocation patients: 137.4 ± 71.1 min, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Postoperative outcomes and complications

On average, dislocation patients had a significantly longer length of stay (LOS) in the hospital (all patients: 2.4 ± 3.1 days, dislocation patients: 4.3 ± 4.5 days, p < 0.001). Much fewer dislocation patients were able to be discharged to home (all patients: 83.3% discharged home, dislocation patients: 60.5% discharged home, p < 0.001). With regards to complications, a greater proportion of dislocation patients experienced deep incision wound surgical site infections (SSI) (all patients: 0.2% SSI, dislocation patients: 0.6% SSI, p = 0.019) as well as organ/space SSI (all patients: 0.3% SSI, dislocation patients: 1.4% SSI, p < 0.001). Dislocation patients also had higher rates of requiring a ventilator for > 48 h postoperatively (all patients: 0.1%, dislocation patients: 0.3%, p = 0.008) in addition to acute renal failure, urinary tract infection, stroke/cerebral vascular accident (CVA), postoperative coma for > 24 h, transfusion, deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/thrombophlebitis and sepsis and septic shock complications (all p < 0.05). Dislocation patients were almost 3 times as likely to be readmitted and require reoperation (all patients: 3.8%, dislocation patients: 10.5%, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Multivariate and bivariate regression results

In a bivariate logistic model, severe eGFR (OR: 2.814, 95% CI: 1.902–4.161), low sodium (OR: 2.036, 95% CI: 1.671–2.482), higher preoperative BUN (OR: 1.010, 95% CI: 1.004–1.017), higher preoperative serum Cr (OR: 1.139, 95% CI: 1.049–1.235), a BUN/Cr ratio of 25 + (OR: 1.180, 95% CI: 1.022–1.363), hypoalbuminemia (OR: 4.847, 95% CI: 4.038–5.819), an alkaline phosphatase > 148 (OR: 3.261, 95% CI: 2.444–4.351), higher WBC count (OR: 1.769, 95% CI: 1.348–2.321), mild (OR: 2.761, 95% CI: 2.400–3.178) and moderate/severe anemia (OR: 6.400, 95% CI: 5.436–7.535) and higher preoperative INR (OR: 1.271, 95% CI: 1.118–1.445) were all individually associated with a greater risk of prosthetic hip dislocation following primary THA (all p < 0.05) (Table 3).

In a multivariate logistic model for BMI levels and prosthetic dislocation risk, the underweight patients were more at risk for dislocation (OR: 2.699, 95% CI: 1.953–3.729, p < 0.001) whereas the overweight (OR: 0.629, 95% CI: 0.543–0.730, p < 0.001), obese class I & 2 (OR:0.599, 95% CI: 0.519–0.692, p < 0.001) and obese class III (OR: 0.554, 95% CI: 0.428–0.717, p < 0.001) were less at risk compared to healthy BMI patients [14] (Table 4).

Furthermore, in a multivariate logistic model examining the effects of demographic data, preoperative laboratory values, recorded past medical history, THA operative details and select outcomes on risk for prosthetic hip dislocation, multiple variables were associated with greater risk. For instance, hypoalbuminemia (OR: 2.174, 95% CI: 1.650–2.864), moderate/severe anemia (OR: 2.098, 95% CI: 1.554–2.832), general anesthesia (OR: 2.092, 95% CI: 1.640–2.668), longer operative time (OR: 1.007, 95% CI: 1.006–1.008) and longer length of hospital stay (OR: 1.012, 95% CI: 1.003–1.021) all correlated with increased risk for prosthetic hip dislocation (all p < 0.05). Additionally, American Indian race was associated with greater risk for dislocation (OR: 2.459, 95% CI:0.998,6.055), p = 0.050). Contrarily, discharge to home was associated with decreased risk of dislocation (OR: 0.582, 95% CI: 0.469–0.722, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Lastly, in a multivariate model for risk of postoperative complications associated with prosthetic dislocation, stroke/CVA (OR: 2.894, 95% CI: 1.181–7.093), bleeding requiring transfusion (OR: 5.092, 95% CI: 4.475–5.794) and sepsis (OR: 3.232, 95% CI: 1.887–5.536) were significant (all p < 0.05) (Table 6).

Discussion

Early identification and recognition of preoperative risk factors for THA dislocations is an important component of interdisciplinary surgical planning and physician–patient communication on expected outcomes [3, 20, 21]. With the recent emphasis on value-based healthcare models, it is essential for surgeons to adequately optimize patients prior to surgery to reduce inpatient costs, facilitate speedy functional rehabilitation, reduce hospital readmissions, and decrease LOS [22]. While the surgical techniques and implants have advanced to decrease dislocation rates in susceptible elderly patients, there is still a component of pre-operative lab values, medical history, and perioperative care that needs to be further explored and standardized. Elderly patients undergoing arthroplasty are susceptible to dislocation complications due to relative medical frailty and are prone to underlying disabilities and fatigue limiting their quality of life and ability to return to functional independence [23]. This study found American Indian ethnicity, hypoalbuminemia, moderate to severe anemia, general anesthesia, increased operative time, and longer inpatient hospital stay to be independent risk factors for postoperative dislocation within 30 days. Risk stratification and medical clearance are essential components of surgical planning and optimization surgeons can take to prevent acute dislocations and reduce overall healthcare costs.

When baseline demographics were compared against non-dislocated patients, patients with 30-day postoperative hip dislocations were more likely to be females, older age, higher ASA classification, lower BMI, diabetics, smokers, and have a history of hypertension, bleeding disorders, and COPD. Similar to prior studies, older age, higher ASA, and COPD predict overall frailty among these patients which may contribute to underlying poor muscular resistance and tension needed to prevent dislocation events [24]. Smokers, diabetics, and patients with COPD have previously been shown to have increased prosthesis-related complications, including aseptic loosening, infections, and revisions which may stem from poor circulatory function and bone-implant integration leading to dislocation [25]. While some studies found a higher BMI to be a risk factor for dislocation possibly due to extra-articular impingement from thigh-on-thigh soft tissue contact during head adduction and flexion, our study suggested a lower BMI may instead be more susceptible to future dislocations [26]. A low BMI, especially < 18.5 is more likely to predict muscle weakness leading to ligamentous laxity, while obesity is associated with limited mobility and hence less risk of dislocations due to generalized immobility and disuse [27].

On multivariate analysis, American Indian ethnicity was an independent risk factor for sustaining a postoperative hip dislocation. Although prior studies have suggested White ethnicity to increase the risk of dislocation, there are limited studies on ethnic disparities, and disparities in THA are still relatively unknown with a lack of robust data. While a prior study has shown minorities to have an increased LOS and American Indians specifically with increased THA reoperation rates, our study suggests the inherent risk of dislocation in American Indians may be the cause for the higher return to the operating room [28]. American Indian patients have some of the highest adverse health outcomes after total knee arthroplasty, and future studies are needed to address ethnic disparities in THA causing postoperative dislocations that may be prevented by understanding underlying social determinants of health [29]. Socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, cultural beliefs, and neighborhood are currently discussed topics that are starting to become integrated into the perioperative optimization and comprehensive value-based approach to healthcare [30].

Hypoalbuminemia has been regularly used in the orthopedic literature to suggest malnutrition and frailty. While severely low GFR, history of renal complications, and recent weight loss > 10% predicted high rates of dislocation, only hypoalbuminemia was an independent risk factor for dislocation on multivariate linear regression. Hypoalbuminemia is considered to represent inadequate nutritional status and chronic inflammation leading to poor muscle mass and strength [31]. The decreased strength and muscle weakness likely contribute to increased dislocation risk due to imbalance, inability to comply with activity restrictions, and poor lower chain mobility with dynamic sit to stand maneuvers [32]. Our patients with hypoalbuminemia and malnutrition likely required increased hospitalization stay and discharge to acute rehabilitation for dependent gait assistance, strengthening, and safety precaution. In fact, increased LOS and a non-home discharge destination were also independent risk factors for sustaining a postoperative dislocation on multivariate analysis. A decreased LOS and discharge home not only help reduce health care utilization costs but also improve recovery in the comfort of the patient’s home by decreasing iatrogenic complications and infections. Although our study investigated the utility of a 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index on predicting dislocation risk, there was no significant correlation between the mFI-5 and prediction of 30-day dislocation [19]. Implementation of a postoperative protein-based diet after hip fracture surgery has previously been associated with lower complication rates, and surgeons should consider nutrition consultation, vitamin supplementation, and emphasis on a high-protein diet to decrease dislocation rate, decrease frailty, improve muscular strength, and reduce overall medical complications [33].

Preoperative lab markers are routinely ordered to stratify at risk patients for medical complications, but there are few studies examining risk factors and values that predict propensity for dislocations [34]. In this study, a low eGFR, hyponatremia, BUN/Cr > 25, high alkaline phosphatase levels, leukocytosis, anemia, and a high INR level were associated with postoperative dislocation events (Table 4). However, it is important to note that the INR was statistically significant, a difference of 0.1 is likely not clinically significant. GFR and hyponatremia are preoperative risk factors that reflect underlying fluid balance and circulatory deficiencies that increase the risk of postoperative falls, delirium, cognitive impairment, and medical complications that increase the risk for dislocation [35]. A high BUN/Cr > 25 is a sensitive marker for dehydration, and dehydrated patients in the post-surgical period are prone to underlying disabilities and fatigue, which may preclude safe, proper adherence to postoperative posterior hip precautions for preventing dislocation [36]. In addition, high alkaline phosphatase levels may reflect an underlying abnormality in bone quality and density that may not be able to withstand stresses from prosthetic impaction, reaming, broaching, and early weight bearing [37]. Perhaps due to poor bone healing and underlying malnourishment, our high alkaline phosphatase, hyponatremic, dehydrated, and coagulopathic patients had an increased risk of postoperative dislocations from overall frailty and poor soft tissue integrity. In fact, among our preoperative lab values, multivariate analysis revealed anemia to be an independent risk factor for postoperative dislocations. Anemic patients are susceptible to post anesthetic and stresses of surgery, and they are prone to sustaining falls and orthostatic hypotensive episodes leading to dislocation [38]. Proper preoperative treatment of anemia may reduce postoperative weakness and fatigue that may lead to improved balance, rehabilitation, and gait training needed to decrease dislocation rates.

In addition to the preoperative risk stratification of patients who may be susceptible to complications, it is important for surgeons to identify perioperative factors, such as type of anesthesia and operative time, as independent risk factors for dislocation. In our multivariate logistic regression, general anesthesia and increased operative time were significantly associated with dislocation events. General compared to spinal anesthesia for hip surgery has previously been shown to decrease mortality, thromboembolic events, blood loss, pulmonary complications, and transfusion requirements [39]. Decreased postoperative complications may allow for early functional rehabilitation and decreased length of inpatient stay, further decreasing the rate of dislocation events. A prior study has examined the possible benefits of a motor blockade and resultant soft tissue laxity seen intraoperatively during THA on spinal anesthesia patients that lead to perceived vertical offset and further soft tissue tensioning leading to overall decreased dislocation rates [40]. Furthermore, increased operative time was also an independent risk factor for dislocation in this study, possibly due to overall increased anesthesia combined with difficulty of the case leading to higher dislocation rates [41].

Not only are readmissions and reoperation rates for THA dislocations costly and increase morbidity, but patients presenting with dislocated THA are also at increased risk for sustaining further cerebrovascular accidents, bleeding requiring transfusion requirements, and sepsis. Periprosthetic dislocations cause increased tension on neurovascular structures and soft tissue disruption, leading to hemorrhage and deep hematoma formation [41]. The deep hematoma and underlying bleeding may cause acute blood loss anemia requiring postoperative transfusions, which are known to increase overall morbidity, outcomes, and infections in THA [42]. Stasis of the hematoma in combination with allogenic transfusions may lead to infections of the hip and further sepsis if not addressed immediately and carefully monitored. Perioperative immobilization and venous disruption caused by traumatic dislocation events may possibly also lead to higher risk of undiagnosed thromboembolism causing increased cerebrovascular accident rates as seen in this study.

Despite the large number of patients included, there are limitations to consider when using the NSQIP database, including selection bias. Although we were able to analyze all primary THA using CPT codes, there was unfortunately no ability to assess anterior versus posterior approach, conventional versus navigation assisted techniques, and the type of implants, such as dual mobility cups, constrained liners, or high offset stems. The anterior approach has gained increasing popularity for high-risk patients, and this national database was unable to differentiate concurrent spine pathology, which has been shown to be an independent risk factor for dislocation [43, 44]. While the data consists of a heterogeneous population nationwide at different ambulatory settings, the wide variety of in-patient hospitals and surgeon expertise may confound outcomes. Although various institutions may implement different preoperative pathways for joint arthroplasty, patients from both academic and private practice settings in rural and urban centers reflect the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, it is possible that we were not able to record all cases of postoperative periprosthetic dislocations as the database is limited to short 30-day complication rates. Lastly, the database does not include variables involving mental status or mental health, which is increasing important in modern healthcare.

Risk stratification and medical clearance are essential components of surgical planning to reduce dislocation events and decrease healthcare costs. Patients with preoperative hypoalbuminemia, moderate to severe anemia, American Indian ethnicity, and non-home discharge are at risk for sustaining acute dislocations after index THA. Perioperative risk factors, such as general anesthesia, increased operative time, and increased length of inpatient hospital stay are modifiable factors that further increase risk for dislocation in susceptible patients. Careful interdisciplinary planning and medical optimization should be considered in high-risk frail patients as postoperative dislocations significantly increase the risk of sepsis, CVA, and blood transfusions on readmission.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database at https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip.

Abbreviations

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- NSQIP:

-

National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

- CPT:

-

Current Procedural Terminology

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- US:

-

United States

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- PRBCs:

-

Packed red blood cells

- SIRS:

-

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- SSI:

-

Surgical site infection

- CVA:

-

Cerebral vascular accident

- DVT:

-

Deep vein thrombosis

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

References

Bayliss LE, Culliford D, Monk AP et al (2017) The effect of patient age at intervention on risk of implant revision after total replacement of the hip or knee: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 389(10077):1424–1430. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30059-4

Paxton EW, Inacio MC, Singh JA, Love R, Bini SA, Namba RS (2015) Are There Modifiable Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission After Total Hip Arthroplasty in a US Healthcare System? Clin Orthop Relat Res 473(11):3446–3455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4278-x

Schairer WW, Sing DC, Vail TP, Bozic KJ (2014) Causes and frequency of unplanned hospital readmission after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(2):464–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3121-5

De Martino I, D’Apolito R, Soranoglou VG, Poultsides LA, Sculco PK (2017) Dislocation following total hip arthroplasty using dual mobility acetabular components: a systematic review. Bone Joint J 99-B(ASuppl1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0398.R1

Miller LE, Gondusky JS, Kamath AF, Boettner F, Wright J, Bhattacharyya S (2018) Influence of surgical approach on complication risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 89(3):289–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2018.1438694

Neri T, Philippot R, Farizon F, Boyer B (2017) Results of primary total hip replacement with first generation Bousquet dual mobility socket with more than twenty five years follow up. About a series of two hundred and twelve hips. Int Orthop 41(3):557–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3373-2

Soong M, Rubash HE, Macaulay W (2004) Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 12(5):314–321. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200409000-00006

Duarte GC, Catanoce AP, Zabeu JL et al (2021) Association of preoperative anemia and increased risk of blood transfusion and length of hospital stay in adults undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty: An observational study in a single tertiary center. Health Sci Rep 4(4):e448. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.448

Fessy MH, Putman S, Viste A et al (2017) Erratum to “What are the risk factors for dislocation in primary total hip arthroplasty? A multicenter case-control study of 128 unstable and 438 stable hips” [Orthop. Traumatol. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 103(7):1137

Johnson RL, Abdel MP, Frank RD, Chamberlain AM, Habermann EB, Mantilla CB (2019) Impact of Frailty on Outcomes After Primary and Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 34(1):56-64.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.09.078

Eminovic S, Vincze G, Eglseer D et al (2021) Malnutrition as predictor of poor outcome after total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop 45(1):51–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04892-4

Arnold NR, Samuel LT, Karnuta JM, Acuña AJ, Kamath AF (2020) The international normalised ratio predicts perioperative complications in revision total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int 32(5):661–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120700020973972

Khoshbin A, Hoit G, Nowak LL, Daud A, Steiner M, Juni P et al (2021) The association of preoperative blood markers with postoperative readmissions following arthroplasty. Bone Jt Open 2(6):388–396. https://doi.org/10.1302/2633-1462.26.Bjo-2021-0020

Lung BE, Kanjiya S, Bisogno M, Komatsu DE, Wang ED (2019) Preoperative indications for total shoulder arthroplasty predict adverse postoperative complications. JSES Open Access 3(2):99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jses.2019.03.003

Lung BE, Kanjiya S, Bisogno M, Komatsu DE, Wang ED (2019) Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in total shoulder arthroplasty. JSES Open Access 3(3):183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jses.2019.07.003

Fu MC, Boddapati V, Dines DM, Warren RF, Dines JS, Gulotta LV (2017) The impact of insulin dependence on short-term postoperative complications in diabetic patients undergoing total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 26(12):2091–2096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2017.05.027

Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, Rowell KS, Bartzokis K, Tomeh MG et al (2010) Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 210(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031

Sebastian AS, Polites SF, Glasgow AE, Habermann EB, Cima RR, Kakar S (2017) Current Quality Measurement Tools Are Insufficient to Assess Complications in Orthopedic Surgery. J Hand Surg Am 42(1):10–5.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.09.014

Traven S, Reeves RA, Sekar M, Slone HS, Walton ZJ (2018) New 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index Predicts Morbidity and Mortality in Primary Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 34(1):140–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.09.040

Saucedo JM, Marecek GS, Wanke TR, Lee J, Stulberg SD, Puri L (2013) Understanding readmission after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: who’s at risk? J Arthroplasty 29:256–260

Soohoo NF, Farng E, Lieberman JR, Chambers L, Zingmond DS (2010) Factors that predict short-term complication rates after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468:2363–2371

Mukand JA, Cai C, Zielinski A, Danish M, Berman J (2003) The effects of dehydra- tion on rehabilitation outcomes of elderly orthopedic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 84(1):58–61

Kumar VN, Redford JB (1984) Rehabilitation of hip fractures in the elderly. Am Fam Physician 29:173–180

Decramer M, Lacquet LM, Fagard R, Rogiers P (1994) Corticosteroids contribute to muscle weakness in chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150(01):11–16

Teng S, Yi C, Krettek C, Jagodzinski M (2015) Smoking and risk of prosthesis-related complications after total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. PLoS ONE 10(04):e0125294

Kim Y, Morshed S, Joseph T, Bozic K, Ries MD (2006) Clinical impact of obesity on stability following revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 453:142–146

McClung CD, Zahiri CA, Higa JK, Amstutz HC, Schmalzried TP (2000) Relationship between body mass index and activity in hip or knee arthroplasty patients. J Orthop Res 18(1):35–39

Ezomo OT, Sun D, Gronbeck C, Harrington MA, Halawi MJ (2020) Where Do We Stand Today on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities? An Analysis of Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty From a 2011–2017 National Database. Arthroplast Today 6(4):872–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2020.10.002

Braveman P, Gottlieb L (2014) The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 129(Suppl 2):19–31

Okike K, Chan PH, Prentice HA, Navarro RA, Hinman AD, Paxton EW (2019) Associ- ation of race and ethnicity with total hip arthroplasty outcomes in a univer- sally insured population. J Bone Joint Surg Am 101(13):1160

Snyder CK, Lapidus JA, Cawthon PM, Dam TT, Sakai LY, Marshall LM (2012) Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Research Group. Serum albumin in relation to change in muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle power in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(9):1663–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04115.x

Woolson ST, Rahimtoola ZO (1999) Risk factors for dislocation during the first 3 months after primary total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty 14(6):662–668

Botella-Carretero JI, Iglesias B, Balsa JA, Arrieta F, Zamarrón I, Vázquez C (2010) Perioperative oral nutritional supplements in normally or mildly undernourished geriatric patients submitted to surgery for hip fracture: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr 29(5):574–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.012

Kunutsor SK, Barrett MC, Beswick AD, Judge A, Blom AW, Wylde V, Whitehouse MR (2019) Risk factors for dislocation after primary total hip replacement: meta-analysis of 125 studies involving approximately five million hip replacements. Lancet Rheumatol 1(2):e111–e121. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2665-9913(19)30045-1

Cunningham E, Gallagher N, Hamilton P, Bryce L, Beverland D (2021) Prevalence, risk factors, and complications associated with hyponatraemia following elective primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Perioper Med (Lond) 10(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-021-00197-1

Statz JM, Odum SM, Johnson NR, Otero JE (2021) Failure to Medically Optimize Before Total Hip Arthroplasty: Which Modifiable Risk Factor Is the Most Dangerous? Arthroplast Today 10:18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2021.05.021

Park JC, Kovesdy CP, Duong U et al (2010) Association of serum alkaline phos- phatase and bone mineral density in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int 14:182–192

Adey D, Kumar R, McCarthy JT, Nair KS (2000) Reduced synthesis of muscle proteins in chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 278(2):E219–E225

Opperer M, Danninger T, Stundner O, Memtsoudis SG (2014) Perioperative outcomes and type of anesthesia in hip surgical patients: An evidence based review. World J Orthop 5(3):336–343. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.336

Sathappan SS, Ginat D, Patel V, Walsh M, Jaffe WL, Di Cesare PE (2008) Effect of anesthesia type on limb length discrepancy after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 23(02):203–209

Durand WM, Long WJ, Schwarzkopf R (2020) Readmission for Early Prosthetic Dislocation after Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Hip Surg 4:23–32

Saleh A, Small T, Chandran Pillai AL, Schiltz NK, Klika AK, Barsoum WK (2014) Allogenic blood transfusion following total hip arthroplasty: results from the nationwide inpatient sample, 2000 to 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96(18):e155. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.M.00825

Murphy MP, Schneider AM, LeDuc RC, Killen CJ, Adams WH, Brown NM (2022) A Multivariate Analysis to Predict THA Dislocation with Preoperative Diagnosis, Surgical Approach, Spinal Pathology, Cup Orientation, and Head Size. J Arthroplasty 37(1):168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.08.031

Weir CB, Jan A. BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points. [Updated 2021 Jun 29]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541070/

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There was no funding provided or utilized for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BL, MD, SY, DS, and WM analyzed and interpreted the data. BL, MD, and TT were involved in drafting the manuscript. MD was involved in statistical analysis. RS, DS, WM, SY were involved in revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As this is a retrospective database study, it was considered exempt by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board. Thus, no informed consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

No individual data is presented in this manuscript in any form and thus consent for publication was not obtained.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lung, B.E., Donnelly, M.R., Callan, K. et al. Preoperative demographics and laboratory markers may be associated with early dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. J EXP ORTOP 10, 100 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-023-00659-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-023-00659-z