Abstract

We analyze the regional tsunami hazard along the Sea of Japan coast associated with 60 active faults beneath the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. We generate stochastic slip distribution using a Monte Carlo approach at each fault, and the total number of required earthquake samples is determined based on convergence analysis of maximum coastal tsunami heights. The earthquake recurrence interval on each fault is estimated from observed seismicity. The variance parameter representing aleatory uncertainty for probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis is determined from comparison with the four historical tsunamis, and a logic-tree is used for the choice of the values. Using nearshore tsunami heights at the 50 m isobath and an amplification factor by the Green’s law, hazard curves are constructed at 154 locations for coastal municipalities along the Sea of Japan coast. The highest maximum coastal tsunamis are expected to be approximately 3.7, 7.7, and 11.5 m for the return periods of 100-, 400-, and 1000-year, respectively. The results indicate that the hazard level generally increases from southwest to northeast, which is consistent with the number and type of the identified fault systems. Furthermore, the deaggregation of hazard suggests that tsunamis in the northeast are predominated by local sources, while the southwest parts are likely affected by several regional sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While our attention is drawn to the Pacific coast of Japan due to the past occurrences of damaging tsunamis in major subduction zones such as the Japan Trench and the Nankai Trough, its counterpart on the Sea of Japan coast poses non-negligible tsunami hazards. The Sea of Japan is known to host large tsunamis generated by submarine earthquakes (M > 7) on several active fault systems along its eastern margin. The most recent damaging tsunami was generated by the 1993 Hokkaido Nansei-oki earthquake of magnitude assigned by Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) (MJMA) 7.8, causing a maximum run-up height of more than 30 m on Okushiri Island in Hokkaido (Shuto and Matsutomi 1995). In 1983, an earthquake of MJMA 7.7 (known as the 1983 Sea of Japan earthquake) occurred off the Sea of Japan coast of Tohoku (Satake 1989). The highest recorded tsunami run-up of this event was approximately 15 m in the northern part of Akita prefecture (Shuto 1983). The 1964 Niigata earthquake (Abe 1978) with magnitude (MJMA) 7.5 induced a tsunami with maximum measured inundation height of ~ 6 m. The 1940 Shakotan-oki earthquake with MJMA of 7.5 (Satake 1986) also generated tsunami with heights of ~ 3 m (Ohsumi and Fujiwara 2017). Additionally, historical studies also reported tsunamis, for example, in 1741 around Oshima-Oshima volcano (Satake 2007) and 1833 off Yamagata prefecture (Hatori 1990). Furthermore, ancient tsunamis dating back to 3000 years ago in the region were revealed from tsunami deposits (e.g., Kawakami et al. 2017; Ioki et al. 2019).

The aforementioned tsunami events in the Sea of Japan were responsible for considerable destructions and casualties. The 1993 tsunami severely hit the southernmost part of Okushiri Island overtopping 4.5-m seawalls (Shuto and Fujima 2009). The number of casualties in consequence of the event was reported to be more than 200 people (Watanabe 1998). Damages in fishing ports due to the 1983 tsunami were assessed by Hata et al. (1995), and more than 100 people were killed in Hokkaido, Aomori, and Akita prefectures, as well as two deaths in Korea (Watanabe 1998). The total loss of life from the earthquake and tsunami of the 1964 event was estimated at 26 people, and 1960 houses were destroyed (Abe 1995). Lastly, the 1940 tsunami struck the northwestern coast of Hokkaido and killed 10 people (Satake 1986). Therefore, it is evident that the Sea of Japan coast is at substantial risk from tsunamis.

A Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Assessment (PTHA) is a consistent approach to estimate long-term hazard in regions that are likely exposed to tsunamis, incorporating uncertainty information into the analysis (Grezio et al. 2017). Although the PTHA can be extended to account for nonseismic causative sources (Pampell-Manis et al. 2016; Salmanidou et al. 2019) or to examine the hazard level in a great detail on local scales through tsunami inundation modeling (e.g., Li et al. 2018; Sepúlveda et al. 2019; Volpe et al. 2019), here we limit the analysis to model the frequency of solely earthquake-generated tsunamis that occur in the Sea of Japan and appraise their regional impacts in coastal municipalities along the Sea of Japan coast. The result is expected to provide a general overview on the characteristic of tsunami hazard around the study area, at 154 coastal locations for municipalities along the Sea of Japan coast, facilitating future regional mitigation efforts, decision-making, or development planning.

Active faults in the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan

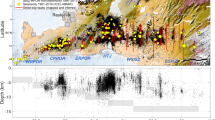

Active fault systems considered in this study consist of relatively moderate- to large-sized (Mw 6.8–7.9) faults scattered in the seismogenic regime of the Sea of Japan (Fig. 1), where a single fault can be formed as an ensemble of smaller segments (see Fig. 2a). A total of 60 faults named F01 to F60 were identified by a government committee (we call it MLIT) jointly supported by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and the Cabinet Office of Japan, based on seismic reflection surveys (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism 2014). The MLIT estimated the fault parameters such as fault length, width, dip, and depth, as well as rake angles based on tectonic stress fields and average slip using a scaling relation (Additional file 2: Table S1). The MLIT model adopts two-levels (average and large slips) of slip distribution to consider the heterogeneity. In our study, to generate realistic heterogeneous slip patterns for earthquake scenarios of the PTHA, we develop a Monte Carlo-type simulation that will be discussed further in the later section.

Tsunami Green’s function

Similar to previous studies (Horspool et al. 2014; Davies et al. 2018), we measure a tsunami intensity in terms of maximum coastal heights calculated from a precomputed tsunami Green’s function. The Green’s function is constructed by discretizing each of the 60 faults into a 10 km × 10 km grid size, resulting in a total 994 subfaults. Then, using a unit slip amount of 1 m and assuming an instantaneous deformation, we calculate initial sea surface displacements by Okada’s model (Okada 1985) including Kajiura’s filter (Kajiura 1963) and coseismic horizontal displacements of ocean bottom (Tanioka and Satake 1996). Subsequently, we run tsunami simulations from each subfault, and record the corresponding tsunami waveforms at 154 locations of interest along the 50-m isobaths, which are the closest points to the coastal municipality offices along the Sea of Japan coast. The list of considered municipalities can be found in Additional file 3: Table S2.

We solve the linear shallow water equations using a tsunami calculation code called JAGURS (Baba et al. 2015, 2017), which has been used in many tsunami studies (e.g., Mulia et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018). We run the tsunami model for 6-h simulation time. The model consists of a two-level nested grid system with grid sizes of 30 and 10 arc-sec (~ 900 m and ~ 300 m in longitude direction) to simulate tsunami propagation at deeper waters and nearshore, respectively. Bathymetry data for the larger grid size is taken from the GEBCO_2014 Grid (Weatherall et al. 2015), while the smaller one is resampled from the M7000 digital bathymetric series issued by the Japan Hydrographic Association. Finally, for the PTHA analysis, we assume that the tsunami height is calculated at a water depth of 1 m with the amplification governed by the Green’s law. Such an empirical amplification law is typically used as a rough estimator of coastal tsunami impacts to substitute the costly detailed numerical modeling. However, Hébert and Schindelé (2015) demonstrated that the approach is dependent on the specific characteristic of coastal response and model resolution, thus leads to inconsistent approximation accuracy at different locations. In the PTHA, the said discrepancy is regarded as aleatory uncertainty, which can be incorporated in the modeled hazard (e.g., Sørensen et al. 2012; Horspool et al. 2014; Davies et al. 2018).

Stochastic slip model

Mai and Beroza (2002) developed a method to characterize complexity of earthquake slip represented by a spatial random field of anisotropic wavenumber spectra according to a von Karman autocorrelation function. The method is implemented in a software package called SlipReal (http://equake-rc.info/cers-software/rupgen/, accessed 1 April 2020). Using a scaling relation established by Wells and Coppersmith (1994), fault length, width, and mean slip are calculated for a given magnitude in the MLIT model. Then, parameters of the von Karman correlation function such as correlation lengths along the strike and downdip, and the Hurst exponent are determined using an empirical formula for the calculated fault length and width (Mai and Beroza 2002). The correlation lengths define the heterogeneity of small wavenumber components, while the Hurst exponent determines the spatial decay in the large wavenumber range. The stochastic nature of the method is attributed to the uniformly distributed random phase angles embedded in the frequency domain, by which spectral characterization of the slip distribution is then transformed into the spatial domain through an inverse Fourier transform.

In our study, the random slip is initially calculated on 1 km × 1 km grid spacing, then the result is interpolated into the specified subfault size to facilitate the tsunami Green’s function computation. We apply a bilinear interpolation without altering the mean slip, hence preserve the moment magnitude of the interpolated sample. We use maximum magnitude values proposed by MLIT, and set a minimum magnitude of Mw 6.5 at all the 60 faults. This results in different number of samples at each fault, as we fix a magnitude bin of 0.1. Besides the random slip distribution, we also randomize the rupture area of small earthquakes occurring on a larger fault dimension. For example, as shown in Fig. 2b, the slip region of relatively small-sized earthquakes take place only on a certain portion of the entire fault. The location of these earthquakes is determined arbitrarily on the predefined subfaults, which is to some extent similar to approaches by Mori et al. (2017) and Mulia et al. (2019).

Analysis of the Monte Carlo convergence

We perform a statistical analysis to estimate the required number of samples at each magnitude bin, reflecting the convergence of Monte Carlo samples in terms of coastal tsunami heights with respect to sources from the identified active faults. We apply a statistical measure that shows the extent of variability of samples around the mean using a coefficient of variation, \(CV = \sigma /\mu\), where \(\sigma\) and \(\mu\) is the standard deviation and mean of maximum coastal tsunami heights at all coastal points, respectively, obtained by applying the stochastically generated slip to the precomputed Green’s function. At each magnitude bin for all the 60 faults, we calculate the coefficient of variation at every increment of samples from 2 to 250. Note that the maximum magnitude varies at each fault (see Additional file 2: Table S1).

As an example, we plot the results from F01, F42, and F60 in Fig. 3, which depicts the level of variability of maximum coastal tsunami heights from the 250 samples. As expected, the variability increases with the decrease of magnitude owing to the randomization of rupture area of smaller earthquakes. Furthermore, each fault results in different level of variability. For instance, the variation of coastal tsunami heights due to Mw 6.5 earthquakes at F60 is quite stable if more than 150 samples are used. At F01 or F42, the stable condition for the same magnitude of Mw 6.5 is actually achieved with less than 150 samples. However, for simplification, we assume that the minimum required number of samples is 150 for magnitude Mw 6.5 at all the 60 faults. By visual inspection, we apply the same approach to all considered magnitude bins, and qualitatively draw a straight line connecting a point at curves of each magnitude bin, beyond which the fluctuation of coefficient of variation is less prominent. This line marks the requisite number of earthquake scenarios at each magnitude bin, which is summarized in Table 1. Based on this analysis, the total number of scenarios considered in our study is 76,685. Such a large number of samples are expected to account for the epistemic uncertainty on the slip distribution of faults in the PTHA analysis. To further confirm the sample size sufficiency, we also analyze the convergence of hazard results that will be discussed in the results and discussion section.

Synthetic scenarios versus historical events

Once synthetic earthquake scenarios for all the 60 faults using the optimum number of samples have been generated, we calculate the corresponding maximum coastal tsunami heights. We then compare the results from samples with similar earthquake locations and magnitudes to four past earthquake tsunami events. The MLIT faults we compare are: F15 (maximum Mw = 7.8) for the 1993 Hokkaido Nansei-oki earthquake (MJMA = 7.8), F24 (maximum Mw = 7.9) for the 1983 Sea of Japan earthquake (MJMA = 7.7), F34 (maximum Mw = 7.7) for the 1964 Niigata earthquake (MJMA = 7.5), and F07 (maximum Mw = 7.4) for the 1940 Shakotan-oki earthquake (MJMA = 7.5). The measured tsunami inundation heights are obtained from the Japan Tsunami Trace database administered by the International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University (Iwabuchi et al. 2012; http://tsunami3.civil.tohoku.ac.jp/tsunami/kiyaku.php, accessed 10 April 2020). The accuracy of the simulated coastal tsunami heights is evaluated based on the geometric mean ratio K and its corresponding standard deviation \(\kappa\) (Aida 1978). The value of \(\kappa\) will later be used in the PTHA to account for the aleatory uncertainty associated with our model resolution and parameterization.

Figure 4 shows the comparison results and quantification of accuracy for the respective events: the 1940 (K = 1.15, \(\kappa\) = 1.85), the 1964 (K = 0.99, \(\kappa\) = 2.04), the 1983 (K = 0.99, \(\kappa\) = 1.85), and the 1993 event (K = 0.99, \(\kappa\) = 2.19). Note that the evaluation is performed only at the closest observation locations to the predefined coastal points of our locations of interest. Therefore, some of the highest measured inundation heights are not represented in our simulation results. For example, the 15.6 m tsunami height from the 1983 event (Fig. 4c) was measured on a riverbank, which is relatively far from the nearest evaluation point (coastal point 112 in Additional file 3: Table S2) compared to other observation locations. Similarly, in the 1993 event (Fig. 4d), the highest measured maximum tsunami of 31.7 m was induced by local effects due to steep valley and reflections, and was located on the opposite side of the Okushiri island from the nearest evaluation point (coastal point 128 in Additional file 3: Table S2). A more detailed tsunami modeling and small-scaled analysis are needed to properly simulate the tsunami and estimate the associated hazard, but it is beyond the scope of this paper. Furthermore, the four historical events are probably still limited to strongly constraint the uncertainty associated with model accuracies, which is one of the main challenges in the PTHA study (Grezio et al. 2017).

Comparison of simulated versus measured coastal tsunami heights of four historical events: (a) 1940, (b) 1964, (c) 1983, and (d) 1993 near the locations of interest. Gray squares on the maps indicate observation points with the nearest points to the locations of interest (pink dots) marked using green dots. The corresponding coastal tsunami heights are color-coded in the respective right panel. The associated faults are annotated, and earthquake epicenters are shown by black stars. Insets in c, d indicate the locations of the highest measured tsunamis. The K and \(\kappa\) are calculated from the measured heights and the simulated heights after applying the Green’s Law

Tsunami hazard analysis

Adopting a probabilistic seismic hazard assessment introduced by Cornell (1968), the PTHA estimates the exceedance rate of a particular tsunami height \(H\) relative to tsunami height levels \(h\), which in a discrete form can be formulated as:

where \(n_{s}\) is the total number of \(i\) source/fault, and \(n_{m}\) is the number of considered magnitude \(m\) with an interval of \(j\). Here we consider the range of magnitude from the smallest magnitude \(m_{ \hbox{min} }\) to the largest magnitude \(m_{ \hbox{max} }\) with a magnitude bin of 0.1. The variable \(\upsilon\) denotes the rate of occurrence of earthquakes with \(M\) that is equal to or greater than \(m_{ \hbox{min} }\) at each fault calculated using the Gutenberg-Richter frequency magnitude distribution (Ishimoto and Iida 1939; Gutenberg and Richter 1944),

where \(a\) and \(b\) values are constants determined from observed seismicity in the study area, which will be discussed further in the next section. The probability associated with all magnitude ranges in Eq. (1) is derived from the bounded Gutenberg–Richter frequency magnitude distribution,

where \(\Delta m\) is the magnitude bin. For example at F01 fault, with the considered minimum magnitude of 6.5 and maximum magnitude of 7.9, \(m_{ \hbox{min} }\) and \(m_{ \hbox{max} }\) for the analyses are 6.45 and 7.95, respectively. The probability of tsunami height \(H\) exceeding any tsunami height level \(h\) given a magnitude \(m\) in Eq. (1) can be expressed as,

where \(\varPhi\) is the cumulative standard-normal distribution function, \(\overline{{{ \ln }\left( H \right)}}\) is the median of logarithmic tsunami height of all models with a given source and magnitude, and \(\beta\) is the standard deviation of \({ \ln }\left( H \right)\) that can be estimated from a logarithmic standard deviation \(\kappa\) of Aida (1978), such that \(\beta = { \ln }\left( \kappa \right)\).

In the PTHA, \(\beta\) is included to account for aleatory uncertainty related to tsunami simulations and source uncertainties. Thio et al. (2012) proposed a combined uncertainty with a total \(\beta\) value of 0.519, which was also adopted by Horspool et al. (2014), whereas Davies et al. (2018) used a larger \(\beta\) of 0.927 based on a root-mean-square of \(\beta\) values obtained from four historical tsunami events. Other studies by Annaka et al. (2007) and Fukutani et al. (2015) treated the value of \(\beta\) as epistemic uncertainty through a logic-tree approach, in which \(\beta\) ranges from 0.223 to 0.438 corresponding to \(\kappa\) of 1.25 to 1.55. Here, we adopt a similar logic-tree, but using \(\beta\) values from the calculated \(\kappa\) in “Synthetic scenarios versus historical events” section. Since there are two similar \(\beta\) values of 0.615 (from the 1940 and 1983 events), we set the corresponding weight of 0.5, while the other two \(\beta\) values of 0.713 (the 1964 event) and 0.784 (the 1993 event) are each weighted 0.25. Figure 5 shows a schematic of the logic-tree with considered values of weights and \(\beta\). Therefore, Eq. (4) is summed over the branches of the logic-tree and multiplied by the respective weight.

Determination of \(\varvec{a}\) and \(\varvec{b}\) values

Values of \(a\) and \(b\) describe the seismicity level and the ratio between large and small earthquake events in the specified region, respectively. In this study, we use the JMA unified hypocenter catalog over a period of 1997–2017 (https://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/eqev/data/bulletin/hypo_e.html, accessed 12 April 2020), and filter out earthquakes of more than 50 km depth. Then, we employ a software package ZMAP (Wiemer 2001) to map \(a\) and \(b\) values (Fig. 6) in conjunction with the magnitude of completeness \(Mc\) (Additional file 1: Figure S1) into a 0.2 × 0.2 degree grid size based on a maximum curvature method (Wiemer and Wyss 2000), with a sampling radius of 35 km following Nanjo and Yoshida (2018). We apply a correction factor of 0.2 for \(Mc\), and a threshold of 50 minimum number of events above \(Mc\). An example that shows the fit of observed seismicity to the Gutenberg–Richter frequency magnitude distribution within the specified sampling radius is also plotted in Fig. 6. The \(a\) and \(b\) values together with the uncertainty levels at the 60 faults are selected from the closest grid location to the faults, and tabulated in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Maps of \(a\) and \(b\) values determined from the JMA unified hypocenter catalog over a period of 1997–2017. Inset in the right panel shows the fit between observed seismicity and the Gutenberg–Richter frequency magnitude distribution within the specified sampling radius (black circle). Faults are drawn in light gray with bold lines mark the top edge of faults

Results and discussion

As depicted in Fig. 1, we apply the PTHA to six regions on the coast of the Sea of Japan: Hokkaido, Tohoku, Chubu, Kinki, Chugoku, and Kyushu. However, before we proceed with the main analysis, we first test the convergence of hazard in addition to the Monte Carlo convergence evaluation described in “Analysis of the Monte Carlo convergence” section. We split the total scenarios into two parts. For instance, the number of scenarios of a magnitude of Mw 7.9 at F01 is 75 samples as shown in Table 1. These samples are randomly split into two nearly equal-sized groups. The same procedure is applied to all considered magnitude ranges and faults, leading to two large groups with a similar magnitude distribution. We then calculate the hazard curves from the respective part. Additional file 1: Figure S2 shows that the mean regional hazard curves, derived from all coastal points at the same region, of both parts are similar. This suggests the convergence of hazard results, and thus samples size sufficiency. Additionally, we also show the variation of mean regional hazard curves with respect to different \(\beta\) values as estimated in “Synthetic scenarios versus historical events” section together with that resulted by the logic-tree (Additional file 1: Figure S3). This explains the sensitivity of hazard to the \(\beta\) value, which is apparent in longer time scales. In the 1000 year return period, the discrepancy of tsunami heights in Hokkaido, Tohoku, and Chubu regions using the smallest \(\beta\) = 0.615 and the largest \(\beta\) = 0.784 can be of approximately 2 m. Hereafter, we will only refer to the modeled hazard by the logic-tree approach that proportionally balances between the smallest and largest estimates.

Hazard level

The number of hazard curves (locations of interest) in Hokkaido, Tohoku, Chubu, Kinki, Chugoku, and Kyushu regions are 31, 21, 56, 8, 23, and 15, respectively. Figure 7 shows the tsunami hazard curves at each region, suggesting the decrease of hazard from northeast regions (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Chubu) to southwest regions (Kinki, Chugoku, and Kyushu). This is related to the less number of identified faults in the vicinity of southwest regions compared to the northeast. Moreover, the dominant earthquake mechanism in the southwest is strike-slip faulting, while the northeast is mostly characterized by dip-slip faults (Additional file 2: Table S1), which would naturally generate larger tsunamis. Based on the mean and median regional curves, we can see that Tohoku exhibits higher annual exceedance rate for all considered range of tsunami heights compared to other regions. However, a few individual curves at coastal points in Chubu and Hokkaido show comparable or even higher hazards than that of Tohoku, especially at longer return periods of more than 1000 years. While Kinki and Chugoku regions share almost similar regional hazard characteristics, Kyushu exhibits a distinct tsunami hazard curve with the lowest hazard level among others at relatively short time scales. The rate of exceedance of a 0.5-m tsunami in Kyushu has a return period of more than 100 years, but the hazard increases on a longer time scales, where the exceedance of more than 2-m tsunami could occur at the return periods of more than 1000 years. Values of annual exceedance rate to generate tsunami hazard curves at each coastal point (municipality) resulted by our PTHA study can be found in Additional file 3: Table S2.

Individual tsunami hazard curves at the specified coastal points (light blue) including mean and median curves over the respective region depicted in Fig. 1

Using a more detailed tsunami simulation method, one can reveal the influence of coastal structures on the characteristic of tsunami at a particular location through the corresponding hazard curve (De Risi and Goda 2017). In our study, the variability of tsunami hazard curves is only attributed to larger oceanic features such as islands or regional coastal topography or bathymetry, as we focus on the broader impact, regionally represented by the mean or median hazard curve. In addition to the main result, here we analyze the sensitivity of such a regional curve to the \(a\) and \(b\) values. First, we divide the 60 faults into three groups according to specified latitude ranges: group 1 (33°–36°N), group 2 (36°–41°N), and group 3 (41°–47°N). Then the \(a\) and \(b\) values are averaged over these groups, defined as group-averaged. Furthermore, the \(a\) and \(b\) values are then averaged over the entire domain, defined as domain-averaged. The mean tsunami hazard curves resulted by the group- and domain-averaged \(a\) and \(b\) values slightly underestimate the hazard from individual values assigned to each fault (Additional file 1: Figure S4). In Kinki, the discrepancy is even less apparent implying that, at a certain region, the use of averaged seismicity rate parameters over specific areas are sufficient for the PTHA study.

Figure 8 shows the tsunami hazard maps derived from the tsunami hazard curves in Fig. 7. For a 100-year return period, the highest maximum coastal tsunami of approximately 3.7 m is expected to occur in Chubu (coastal point 102 in Additional file 3: Table S2). The same location could experience maximum coastal tsunami heights of approximately 7.7 and 11.5 m for 400- and 1000-year return periods, respectively. These are the highest among other regions. Other significant tsunamis of more than 5 m could also occur in Tohoku and Hokkaido regions in 400-year return period, and more than 8 m in 1000-year return period, while the heights are less than 3 m in 100-year return period. This is in line with a probabilistic study derived from geological data by Suzuki et al. (2018) suggesting that in Hokkaido, the tsunami heights are mostly less than 2 m for a return period of 150 years. The low level of hazard in the southwest area (Kinki, Chugoku, and Kyushu) is clearly delineated by the tsunami hazard maps, where the highest maximum coastal tsunamis of 1.8, 3.3, and 4.6 m appears in Chugoku (coastal point 54 in Additional file 3: Table S2) for 100-, 400-, and 1000-year return periods, respectively. A notable maximum coastal tsunami heights of more than 3 m is also visible in Kyushu (coastal points 7–10 in Additional file 3: Table S2 ) for the return period of 1000 years.

Besides the annual rate of exceedance \(\lambda\) formulated in Eq. (1), an alternative representation of the hazard is in terms of the annual probability of exceedance \(p = 1 - e^{\lambda }\), assuming the Poisson process. Figure 9 shows the annual probability in percentage (\(p \times 100\%\)) of experiencing tsunamis with heights of more than 0.5, 1.5, and 3 m at all coastal points. A threshold of 0.5 m is typically used to initiate a tsunami warning, while a 3 m is used for a major tsunami warning (Strunz et al. 2011; Horspool et al. 2014). Most coastal points in Tohoku, several in Chubu, and one in Hokkaido have more than 10% probability of experiencing maximum coastal tsunami of higher than 0.5 m at any given year. A nearly similar distribution in Tohoku and Chubu is also shown by the 1.5-m tsunami height, but with lower probabilities ranging from 0.1 to 4.1%. For the 3-m or greater coastal tsunami heights, the highest annual probability of exceedance of more than 1.2% are located at two coastal points (coastal point 95 and 102 in Additional file 3: Table S2) in Chubu.

The PTHA results reveal the probability and likelihood of where significant tsunamis could occur. Such information is needed to emphasize tsunami mitigation efforts at locations potentially exposed to greater hazard, or to prepare adequate development plans in relation with tsunami disaster risk reduction. For instance, our regional PTHA result would provide an insight at which region deployment of prospective tsunami observing systems should be prioritized. Along the Sea of Japan coast, it is evident that each region exhibits one or more locations with substantial tsunami heights. However, in general, since the overall hazard in Kyushu, Chugoku, and Kinki are considerably low, more attention should be given to Chubu, Tohoku, and Hokkaido in ensuring an efficient and effective regional tsunami disaster mitigation strategy for the Sea of Japan coast.

Deaggregation

The extension of the PTHA can be used to estimate the contribution of causative sources to the tsunami hazard at locations of interest through a deaggregation analysis. Here we apply the deaggregation of hazard to the most populated coastal city in each region: Otaru city in Hokkaido, Akita city in Tohoku, Niigata city in Chubu, Maizuru city in Kinki, Matsue city in Chugoku, and Fukuoka city in Kyushu. Figure 10 shows hazard deaggregation results in all cities for the return period of 100-year, while the results for the 400- and 1000-year return periods are presented in Additional file 1: Figure S5 and S6, respectively. Additionally, the range of uncertainty of the tsunami hazard curve at the respective city is represented based on a 15th and 85th percentile (Sørensen et al. 2012). Hazard deaggregation results (contribution of each fault in percentage) for the specified cities and return periods are provided in Additional file 4: Table S3.

Hazard deaggregation for the 100-year return period at the most populated city in each region. Four largest fault contributions are annotated in the map. Insets show the corresponding tsunami hazard curve with uncertainty ranges between 15th and 85th percentile. Red lines mark region boundaries. We fix the fault width for visual clarity

For the 100-year return period, the largest contributor to the tsunami hazard of 1.07 m in Otaru is F01 closely followed by F02, that of 3.09 m in Akita is F26, and that of 3.48 m in Niigata is F38. The four largest contributors to the tsunami hazard in these cities are considered as local sources (Fig. 10), as the tsunami from these faults can reach the target city within less than 1 h. In the southwest part, particularly at Maizuru city, three out of four faults with the highest contribution to the tsunami hazard of 1.04 m are regional sources (tsunami arrives in 1–3 h): F28 (6.6%), F41 (5.7%), and F34 (5.5%), while a local source F53 contribution is 5.5%. At Matsue city, the four largest contributors to a maximum coastal tsunami height of 1.34 m is all attributed to the regional sources: F34 (13.0%), F28 (10.2%), F30 (5.7%), and F35 (5.5%). This is likely because the evaluated coastal point is not located on the main beam of tsunami energy from the local sources that is typically propagated perpendicular to the fault strike. Furthermore, based on the numerical simulations, a significant portion of the tsunami energy from earthquake sources offshore Tohoku can be refracted toward Kinki and Chugoku on account of the regional bathymetric profile. Lastly, tsunami hazard in Fukuoka city is predominated by a local source of F60 located extremely close to the evaluation point having the contribution of 61.9%, but the intensity is very small with a maximum tsunami height of only 0.52 m. In general, the deaggregation for 400- and 1000-year return periods show similar pattern, in which tsunamis in the northeast regions are mainly caused by local sources, while the southwest parts, particularly Kinki and Chugoku, are clearly affected by regional sources. This is in line with the previous explanation on the dominant fault mechanism, where faults in the northeast could potentially trigger larger tsunamis than those in the southwest.

The deaggregation analyses further indicate that the risks in northeast regions are not only related to the higher tsunami hazard level, but also due to the large contribution of local sources. Moreover, the actual tsunami heights are expected to be higher at certain sites apart from our locations of interest as proven from historical records. However, a particular event like the 1993 tsunami caused an anomalously high run-up, thus caution should be exercised when incorporating such an extreme value in the PTHA analysis. These local sources raise concerns on the appropriate measure for tsunami mitigation, because near-field tsunamis render a timely warning less effective due to the extremely short lead time. Even with the present most advanced tsunami detection technologies, the efficacy of tsunami early warning systems for near-field events is perhaps still limited. To cope with such a challenging task, Okal (2015) advocated that self-evacuation by educated populations remains the most effective approach for such locally generated tsunamis.

Conclusions

We have applied a PTHA method to the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan region to estimate earthquake-generated tsunami hazard by considering 60 active submarine faults as the potential tsunami sources. The study demonstrates that the tsunami hazard along the Sea of Japan coast increases from southwest to northeast. More specifically, the highest maximum coastal tsunamis of more than 3.7, 7.7, and 11.5 m may occur at a single site in the region with return periods of 100-, 400-, and 1000-year, respectively. This long-term forecast of tsunami hazard can be used to facilitate a regional tsunami disaster mitigation strategy, or as a basis for more detailed analyses. Furthermore, hazard deaggregation results reveal that significant tsunamis along the specified coastline in the northeast regions are primarily triggered by local sources. Consequently, a timely warning can be a major challenge due to the limited lead time. Therefore, countermeasure efforts focusing on the aforementioned issue should be highlighted.

Availability of data and materials

Bathymetric data are based on M7000 series bathymetric digital data published by the Japan Hydrographic Association, and GEBCO_2014 Grid available at https://www.gebco.net/data_and_products/gridded_bathymetry_data/gebco_30_second_grid/. The JMA unified hypocenter catalog is available at https://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/eqev/data/bulletin/hypo_e.html. Tsunami trace database is downloaded from http://tsunami3.civil.tohoku.ac.jp/tsunami/kiyaku.php.

Abbreviations

- PTHA:

-

Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Assessment

- MLIT:

-

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport

- JMA:

-

Japan Meteorological Agency

References

Abe K (1978) Determination of the fault model consistent with the tsunami generation of the 1964 Niigata earthquake. Mar Geod 1(4):313–330

Abe K (1995) Recent great earthquakes and tectonics in Japan. J Phys Earth 43(4):395–405

Aida I (1978) Reliability of a tsunami source model derived from fault parameters. J. Physics Earth 26:57–73

Annaka T, Satake K, Sakakiyama T, Yanagisawa K, Shuto N (2007) Logic-tree approach for probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis and its applications to the Japanese coasts. Pure Appl Geophys 164:577–592

Baba T, Takahashi N, Kaneda Y, Ando K, Matsuoka D, Kato T (2015) Parallel implementation of dispersive tsunami wave modeling with a nesting algorithm for the 2011 Tohoku tsunami. Pure Appl Geophys 172(12):3455–3472

Baba T, Allgeyer S, Hossen J, Cummins PR, Tsushima H, Imai K, Yamashita K, Kato T (2017) Accurate numerical simulation of the far-field tsunami caused by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, including the effects of Boussinesq dispersion, seawater density stratification, elastic loading, and gravitational potential change. Ocean Model 111:46–54

Cornell CA (1968) Engineering seismic risk analysis. Bull Seismol Soc Am 58:1583–1606

Davies G, Griffin J, Løvholt F, Glimsdal S, Harbitz C, Thio HK, Lorito S, Basili R, Selva J, Geist E, Baptista MA (2018) A global probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment from earthquake sources. Geol Soc Spec Publ 456(1):219–244

De Risi R, Goda K (2017) Simulation-based probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis: empirical and robust hazard predictions. Pure Appl Geophys 174(8):3083–3106

Fukutani Y, Suppasri A, Imamura F (2015) Stochastic analysis and uncertainty assessment of tsunami wave height using a random source parameter model that targets a Tohoku-type earthquake fault. Stoch Env Res Risk A 29(7):1763–1779

Grezio A, Babeyko A, Baptista MA, Behrens J, Costa A, Davies G, Geist EL, Glimsdal S, González FI, Griffin J, Harbitz CB, LeVeque RJ, Lorito S, Løvholt F, Omira R, Mueller C, Paris R, Parsons T, Polet J, Power W, Selva J, Sørensen MB, Thio HK (2017) Probabilistic Tsunami hazard analysis: multiple sources and global applications. Rev Geophys 55:1158–1198

Gutenberg B, Richter C (1944) Frequency of earthquakes in California. Bull Seismol Soc Am 34:185–188

Hata H, Yamamoto M, Nakayama A, Takeuchi T, Yamamoto J (1995) Hydraulic phenomena and tsunami damages in fishing ports-a case study of the Nihonkai-Chubu earthquake tsunami. In: Tsuchiya Y, Shuto N (eds) Tsunami: progress in prediction, disaster prevention and warning. pp 235–248

Hatori T (1990) Magnitudes of the 1833 Yamagata-Oki Earthquake in the Japan Sea and its Tsunami. Zisin 43:227–232 (In Japanese with English abstract)

Hébert H, Schindelé F (2015) Tsunami impact computed from offshore modeling and coastal amplification laws: insights from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Pure Appl Geophys 172:3385–3407

Horspool N, Pranantyo I, Griffin J, Latief H, Natawidjaja DH, Kongko W, Cipta A, Bustaman B, Anugrah SD, Thio HK (2014) A probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment for Indonesia. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 14:3105–3122

Ioki K, Tanioka Y, Kawakami G, Kase Y, Nishina K, Hirose W, Hayashi KI, Takahashi R (2019) Fault model of the 12th century southwestern Hokkaido earthquake estimated from tsunami deposit distributions. Earth Planets Space 71(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-019-1034-6

Ishimoto M, Iida K (1939) Observations sur les seisms enregistres par le microrsismograph construit dernierement (I). Bull Earthq Res Inst Univ of Tokyo 17:443–478 (in Japanese with French abstract)

Iwabuchi Y, Sugino H, Imamura F, Tsuji Y, Matsuoka Y, Imai K, Shuto N (2012) Development of tsunami trace database with reliability evaluation of Japan coasts. J Japan Soc Civil Eng Ser. 68(2):I_1326–I_1330 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Kajiura K (1963) The leading wave of a tsunami. Bull Earthq Res Inst Univ Tokyo 41:535–571

Kawakami G, Kase Y, Urabe A, Takashimizu Y, Nishina K (2017) Tsunami and possible tsunamigenic deposits along the eastern margin of the Japan Sea. Jour Geol Soc Japan 123(10):857–877 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Li L, Switzer AD, Wang Y, Chan CH, Qiu Q, Weiss R (2018) A modest 0.5-m rise in sea level will double the tsunami hazard in Macau. Sci Adv 4(8):eaat1180

Mai PM, Beroza GC (2002) A spatial random field model to characterize complexity in earthquake slip. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 107(11):ESE-10

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (2014) Investigation for large earthquakes occurring in the Sea of Japan. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. http://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/daikibojishinchousa

Mori N, Muhammad A, Goda K, Yasuda T, Ruiz-Angulo A (2017) Probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis of the pacific coast of Mexico: case study based on the 1995 Colima earthquake tsunami. Front Built Environ 3:34

Mulia IE, Gusman AR, Jakir Hossen M, Satake K (2018) Adaptive tsunami source inversion using optimizations and the reciprocity principle. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 123(12):10–749

Mulia IE, Gusman AR, Williamson AL, Satake K (2019) An optimized array configuration of tsunami observation network off Southern Java, Indonesia. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 124(9):9622–9637

Nanjo KZ, Yoshida A (2018) A b map implying the first eastern rupture of the Nankai Trough earthquakes. Nat Commun 9(1):1–7

Ohsumi T, Fujiwara H (2017) Investigation of offshore fault modeling for a source region related to the Shakotan-Oki Earthquake. J Disaster Res 12(5):891–898

Okada Y (1985) Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space. Bull Seismol Soc Am 75:1135–1154

Okal EA (2015) The quest for wisdom: lessons from 17 tsunamis, 2004–2014. Philos T R Soc A 373(2053):20140370

Pampell-Manis A, Horrillo J, Shigihara Y, Parambath L (2016) Probabilistic assessment of landslide tsunami hazard for the northern Gulf of Mexico. J Geophys Res Oceans 121(1):1009–1027

Salmanidou DM, Heidarzadeh M, Guillas S (2019) Probabilistic Landslide-Generated Tsunamis in the Indus Canyon, NW Indian Ocean, Using Statistical Emulation. Pure Appl Geophys 176(7):3099–3114

Satake K (1986) Re-examination of the 1940 Shakotan-oki earthquake and the fault parameters of the earthquakes along the eastern margin of the Japan Sea. Phys Earth Planet In 43(2):137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9201(86)90081-6

Satake K (1989) Inversion of tsunami waveforms for the estimation of heterogeneous fault motion of large submarine earthquakes: the 1968 Tokachi-oki and 1983 Japan Sea earthquakes. J Geophys Res 94(B5):5627–5636

Satake K (2007) Volcanic origin of the 1741 Oshima-Oshima tsunami in the Japan Sea. Earth Planets Space 59(5):381–390. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352698

Sepúlveda I, Liu PL, Grigoriu M (2019) Probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment in South China Sea with consideration of uncertain earthquake characteristics. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 124(1):658–688

Shuto N (1983) Tsunami caused by the Japan Sea earthquake of 1983. Disasters 7(4):255–258

Shuto N, Fujima K (2009) A short history of tsunami research and countermeasures in Japan. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 85(8):267–275

Shuto N, Matsutomi H (1995) Field survey of the 1993 Hokkaido Nansei-Oki earthquake tsunami. Pure Appl Geophys 144(3–4):649–663

Sørensen MB, Spada M, Babeyko A, Wiemer S, Grünthal G (2012) Probabilistic tsunami hazard in the Mediterranean Sea. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 117:B01305

Strunz G, Post J, Zosseder K, Wegscheider S, Mück M, Riedlinger T, Mehl H, Dech S, Birkmann J, Gebert N, Harjono H, Anwar HZ, Sumaryono G, Khomarudin RM, Muhari A (2011) Tsunami risk assessment in Indonesia. Nat Haz Earth Syst Sci 11:67–82

Suzuki T, Nishioka Y, Murashima Y, Takayama J, Tanioka Y, Yamashita T (2018) Select tsunami considering the cumulative probability of occurrence in coasts of the Japan Sea of Hokkaido. JSCE Proceedings B2(74):439–444. https://doi.org/10.2208/kaigan.74.I_439in Japanese with English abstract

Tanioka Y, Satake K (1996) Tsunami generation by horizontal displacement of ocean bottom. Geophys Res Lett 23(8):861–864

Thio, H (2012) URS Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard System: a user manual. Technical Report URS Corporation, San Francisco, CA, https://www.dropbox.com/s/u7m72dibhn1w7fo/Thio2012-PTHA-Manual-v1.00.pdf?dl=0

Volpe M, Lorito S, Selva J, Tonini R, Romano F, Brizuela B (2019) From regional to local SPTHA: efficient computation of probabilistic tsunami inundation maps addressing near-field sources. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 19:455–469

Wang Y, Satake K, Maeda T, Gusman AR (2018) Data assimilation with dispersive tsunami model: a test for the Nankai Trough. Earth Planets Space 70(1):131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-018-0905-6

Watanabe, H (1998) Comprehensive list of tsunamis to hit the Japanese Islands, University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo pp. 1–236 (in Japanese)

Weatherall P, Marks KM, Jakobsson M, Schmitt T, Tani S, Arndt JE, Rovere M, Chayes D, Ferrini V, Wigley R (2015) A new digital bathymetric model of the world’s oceans. Earth Space Science 2(8):331–345

Wells DL, Coppersmith KJ (1994) New empirical relationships among magnitude, rupture length, rupture width, rupture area, and surface displacement. Bull Seismol Soc Am 84(4):974–1002

Wiemer S (2001) A software package to analyze seismicity: zMAP. Seismol Res Lett 72:373–382

Wiemer S, Wyss M (2000) Minimum magnitude of completeness in earthquake catalogs: Examples from Alaska, the western United States, and Japan. Bull Seismol Soc Am 90(4):859–869

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nobuhito Mori for the discussion and sharing his knowledge on the PTHA.

Funding

The study was supported by the Integrated Research Project on Seismic and Tsunami Hazards Around the Sea of Japan from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IEM performed numerical and statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. TI and ARG involved in the data preprocessing and writing the manuscript. KS and SM led the project and contributed to the result interpretations and writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1–S6. Supplementary figures.

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Fault parameters, a, and b values of the 60 active faults considered in the study.

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Annual rate of exceedance at 154 coastal locations for the municipalities along the Sea of Japan coast.

Additional file 4:

Table S3. Contribution of each fault in percentage to hazard at the specified cities for 100-, 400-, and 1000-year return periods.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mulia, I.E., Ishibe, T., Satake, K. et al. Regional probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment associated with active faults along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth Planets Space 72, 123 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01256-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01256-5