Abstract

We developed a humidity control system in a biaxial friction testing machine to investigate the effect of relative humidity and interlayer cations on the frictional strength of montmorillonite. We carried out the frictional experiments on Na- and Ca-montmorillonite under controlled relative humidities (ca. 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90%) and at a constant temperature (95 °C). Our experimental results show that frictional strengths of both Na- and Ca-montmorillonite decrease systematically with increasing relative humidity. The friction coefficients of Na-montmorillonite decrease from 0.33 (at relative humidity of 10%) to 0.06 (at relative humidity of 93%) and those of Ca-montmorillonite decrease from 0.22 (at relative humidity of 11%) to 0.04 (at relative humidity of 91%). Our results also show that the frictional strength of Na-montmorillonite is higher than that of Ca-montmorillonite at a given relative humidity. These results reveal that the frictional strength of montmorillonite is sensitive to hydration state and interlayer cation species, suggesting that the strength of faults containing these clay minerals depends on the physical and chemical environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smectite occurs ubiquitously in natural fault gouges (Wu 1978; Vrolijk and Van Der Pluijm 1999; Underwood 2007). For example, smectite has been identified from the Nojima Fault in Japan (Ohtani et al. 2000), the San Andreas Fault in the USA (Schleicher et al. 2006; Solum et al. 2006), the Chelungpu Fault in Taiwan (Kuo et al. 2009), and the Japan Trench (Kameda et al. 2015). In addition, the fault gouges often contain smectite at large proportion (Deng and Underwood 2001). Previous studies have indicated that montmorillonite (a common type of smectite) is important in controlling fault strength, due to its extremely low friction coefficient (Summers and Byerlee 1977a; Byerlee 1978; Shimamoto and Logan 1981). However, laboratory experiments on montmorillonite have yielded highly scattered friction coefficient data depending on the physical and chemical conditions, including hydration state (Summers and Byerlee 1977b; Bird 1984; Morrow et al. 1992, 2000, 2017; Brown et al. 2003; Ikari et al. 2007; Faulkner et al. 2011; Behnsen and Faulkner 2012; Bullock et al. 2015), shearing velocity (Logan and Rauenzahn 1987; Saffer et al. 2001; Brown et al. 2003; Saffer and Marone 2003; Moore and Lockner 2007; Tembe et al. 2010; Faulkner et al. 2011; Behnsen and Faulkner 2013; Kubo and Katayama 2015; Oohashi et al. 2015; Bullock et al. 2015; Morrow et al. 2017), clay content (Lupini et al. 1981; Shimamoto and Logan 1981; Logan and Rauenzahn 1987; Brown et al. 2003; Ikari et al. 2007; Takahashi et al. 2007; Tembe et al. 2010; Oohashi et al. 2015), interlayer cations (Müller-Vonmoos and Løken 1989; Behnsen and Faulkner 2013), and temperature (Kubo and Katayama 2015).

Montmorillonites are known to absorb large amounts of water into their crystal structure, and the number of water molecular layer (hydration state) varies with relative humidity (e.g., Mooney et al. 1952). The hydration state of montmorillonite changes also with effective pressure and temperature (Bird 1984; Colten-Bradley 1987), meaning it is important to understand how hydration state influences the frictional strength of montmorillonite with depth. In addition, the interlayer cation species also affects the frictional strength of montmorillonite (Behnsen and Faulkner 2013). Müller-Vonmoos and Løken (1989) studied various cation-exchanged montmorillonites at relatively low normal stress (< 1 MPa). Behnsen and Faulkner (2013) systematically investigated the influence of interlayer cations on frictional strength using cation-exchanged Na-, K-, Ca-, and Mg-montmorillonite saturated with deionized water, and found that K-montmorillonite has a much stronger frictional resistance than Na-, Ca-, or Mg-montmorillonite.

To understand the main controls on fault dynamics, it is necessary to study the effect of hydration state on the frictional strength of montmorillonites with various interlayer cation species. Ikari et al. (2007) conducted systematic frictional experiments to test the effect of hydration state through preparing Ca-montmorillonite with different water content. However, hydration state of montmorillonite is sensitive to relative humidity, which might modify initial water content during experiments, and chemical impurities might influence the layer charge of montmorillonite. In this study, we developed a humidity control system in a biaxial frictional testing machine and investigated the effect of relative humidity and interlayer cations on the frictional strength of montmorillonite.

Methods

Preparation of cation-exchanged montmorillonite

The starting material used in this study was Na-montmorillonite (Kunipia-F, commercially obtained from Kunimine Industry, Japan), which is from the Tsukinuno Mine, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. The grain size of the montmorillonite is < 2 µm, and its chemical composition is Na0.42Ca0.068K0.008(Al1.56Mg0.31Fe(III)0.09Fe(II)0.01)(Si3.91Al0.09)O10(OH)2 (Ito et al. 1993). The material contains small amounts of quartz and calcite (1–2%), and also some soluble impurities (Ito et al. 1993). In addition to Na-montmorillonite, we prepared cation-exchanged Ca-montmorillonite for the frictional experiments. Cation-exchanged montmorillonite was obtained by dispersing montmorillonite in 1 eq/L aqueous solution of CaCl2. The montmorillonite suspension was stirred overnight, and montmorillonite was separated from the suspension by centrifugation. This process was repeated three times. After exchanging the interlayer cations, the montmorillonite was washed two times with distilled water to remove chloride ions. Again, montmorillonite was separated from the suspension by centrifugation. The absence of chloride ions in the montmorillonite was confirmed by using a AgNO3 solution.

The interlayer distances of the Na-montmorillonite and cation-exchanged Ca-montmorillonite were obtained by X-ray diffraction (XRD) at room temperature and relative humidity (Fig. 1). XRD data for oriented specimens showed different interlayer distances between Na-montmorillonite and cation-exchanged Ca-montmorillonite. The basal spacings of Na- and Ca-montmorillonite were 12.96 and 15.72 Å, respectively, meaning that the basal spacing for cation-exchanged Ca-montmorillonite is larger than Na-montmorillonite, which is consistent with previous studies (Morodome and Kawamura 2009; Behnsen and Faulkner 2013). Note that these data were obtained at room humidity, and the basal spacing changes corresponding to the controlled relative humidity during experiments. We also determined the chemical compositions of the Na-montmorillonite and cation-exchanged Ca-montmorillonite by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, and confirmed that the interlayer cations were completely exchanged.

Frictional experiments

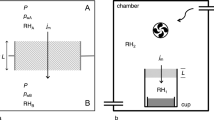

The humidity control system was developed in a biaxial frictional testing machine at Hiroshima University, Japan (see Noda and Shimamoto (2009) for details of the biaxial frictional testing machine). The humidity control system consists of two units: (1) a sample holder (pressure vessel) unit and (2) a steam generating unit (Fig. 2). Using this system, it is possible to independently control the temperatures of the sample holder and steam generator. The relative humidity around the sample is calculated from the difference in vapor pressure between the sample holder and steam generator using Tetens’ equation (Tetens 1930) as follows,

where RH is the relative humidity [%], Tv is the steam temperature [°C], and Tc is the sample holder temperature [°C]. The steam temperature was measured with a thermocouple at the outlet of the steam generating vessel, which was covered by heat insulating materials, and the sample holder temperature was monitored by two thermocouples installed close to the central part of the frictional surfaces (Fig. 2). The error on relative humidity in the experiments was estimated from the temperature variations for each thermocouple in the steam generator and sample holder.

a Schematic representation of the humidity control system. The relative humidity was controlled by the temperature at the sample holder and steam generator. b Schematic representation of the sample setting in the frictional testing machine. The sample holder was heated with an oil and rubber heater, and the temperature of the sample holder was held constant. The horizontal ram applied a constant normal force and the vertical ram applied a shear force at a constant loading velocity. The thermocouple was placed central to the frictional surfaces

The frictional experiments were performed at five values of relative humidity (ca. 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90%), which were calculated from a constant temperature for the sample holder (95 °C) and variable temperature for the steam generator (ca. 44, 64, 77, 85, and 92 °C). Uncertainty of relative humidity comes from variation of temperature during experiments, which was usually less than 7%. Two layers of Na- or Ca-montmorillonite powders (initially 2 g on each side) were sheared within three rough gabbro block surfaces (polished with SiC #80) in a double-direct-shear configuration. The prepared gouge was dried in a vacuum oven for at least 24 h at 100 °C before sample setting. After the sample was set in the machine and heated to 95 °C, the steam was injected into the sample holder at a flow rate of 0.2 L/min. Once the temperature of the sample holder stabilized, the steam temperature was raised to the target value and normal stress was applied. Figure 3 shows an example of benchmark experiments to examine the time equilibrated to vapor pressure at a constant relative humidity of 70%. The frictional strength decrease with increasing time after the steam temperature was raised, and we confirmed that there is a negligible difference in the frictional strengths between 26 and 50 h (Fig. 4), suggesting that the vapor pressure of the gouge layers was nearly equilibrated to that of the sample chamber; consequently, we held for 26 h in each experiments before the samples were sheared. In all experiments, the applied normal stress was 10 ± 0.1 MPa during sliding, and sample were sheared up to 10 mm displacement at a constant velocity of 3 µm/s. The shear displacement was corrected with machine stiffness (4.4 × 108 N/m). The digital sampling data were mostly recorded at 1 Hz before shearing and 10 Hz after shearing using a data logger (EDX-100A Universal Recorder, KYOWA).

Results

Figure 5 shows the results of the frictional experiments for Na- and Ca-montmorillonite. The friction coefficient (µ) was calculated by dividing the shear stress by the normal stress assuming zero cohesion. At low relative humidity, Na-montmorillonite samples developed peak strength at ~ 2 mm shear displacement and exhibited subsequent residual shear strength, whereas the samples did not show a clear peak at high relative humidity. In contrast, Ca-montmorillonite did not show a clear peak in strength at any humidity. Friction coefficients for Na- and Ca-montmorillonite reached a near-steady state at a shear displacement of > 4 mm. All the experimental results are summarized in Table 1. These results indicate a systematic change in friction coefficient with relative humidity. It is noteworthy that the friction coefficients decrease markedly at low to moderate relative humidity but decrease less at moderate to high relative humidity. For example, the friction coefficient of Na-montmorillonite decreases from 0.33 to 0.15 with increasing relative humidity from 10 to 50%, but only changes from 0.15 to 0.06 with increasing relative humidity from 50 to 90%.

The correlation between friction coefficients and relative humidity is shown in Fig. 6. The frictional strength of both Na- and Ca-montmorillonite decreases systematically with increasing relative humidity. At the lowest relative humidity (10%), the friction coefficient is 0.33 for Na-montmorillonite and 0.22 for Ca-montmorillonite, and at the highest relative humidity (90%), the friction coefficient is 0.06 for Na-montmorillonite and 0.04 for Ca-montmorillonite. The friction coefficient of Na-montmorillonite tends to be slightly higher than that of Ca-montmorillonite at a given relative humidity. The difference in friction coefficients between Na- and Ca-montmorillonite is large at low relative humidity (∆µ = 0.11) and smaller at high relative humidity (∆µ = 0.02).

Discussion

Comparison with previous studies

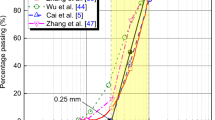

Previously published friction coefficient data for montmorillonite are highly scattered, which may reflect differences in the degree of saturation, impurity, interlayer cation species, and testing conditions (e.g., pressure, temperature, slip velocity and relative humidity). Figure 7 shows our experimental results for Ca-montmorillonite compared with data from previous studies under similar conditions (effective normal stress of 5–25 MPa, temperature up to 100 °C, and maximum loading velocity of 10 µm/s).

Comparison of our experimental data with previous experimental studies of Ca-montmorillonite at effective normal stresses of 5–25 MPa, temperatures up to 100 °C, and loading velocities up to 10 µm/s. The note near the symbols show each water content or experimental condition. The sample of Saffer et al. (2001) has ~ 11 wt% water. Behnsen and Faulkner (2013) carried out experiments under water-saturated condition, and Haines et al. (2013) conducted at room temperature and humidity

The friction coefficients for Ca-smectite (µ = 0.59 at 100 °C and 0.46 at room temperature) determined by Kubo and Katayama (2015) at a normal stress of 15 MPa are higher than our coefficients for cation-exchanged Ca-montmorillonite at a low relative humidity. These relatively high friction coefficients are due to differences in sample impurities, because the frictional strength of fault materials is sensitive to montmorillonite content (e.g., Tembe et al. 2010), and the samples of Kubo and Katayama (2015) contained up to 20% quartz, chalcedony, and cristobalite (Fujita et al. 2011). Carpenter et al. (2016) carried out frictional experiments on Ca-montmorillonite at relative humidity of 100% by placing samples in a sealed chamber with a solution of sodium carbonate and water. They obtained a friction coefficient of 0.215 at normal stress of 20 MPa, which is markedly higher than our result at the highest relative humidity of 90% (µ = 0.04). Their high strength can be caused by impurities in the sample of the experiment (10% impurity). The friction coefficients of Ca-smectite determined at room humidity (water content is ~ 11 wt%) by Saffer et al. (2001) at a normal stress of 10 MPa (µ = 0.3) is higher than our results. These results also might be affected by the impurity of sample, however, they did not describe sample information in detail. The high friction strengths of Ca-montmorillonite have also been reported by Haines et al. (2013) at room humidity, a normal stress of 8 MPa (µ = 0.3) and 20 MPa (µ = 0.27, 0.29). However, it cannot be explained by impurities, because these studies used samples of > 97% purity. The differences might be attributed to interlayer cation compositions, since the non-cation-exchanged sample of their studies contained other cations such as sodium and potassium than our completely cation-exchanged sample. The effect of hydration state on the frictional properties of montmorillonite was systematically investigated by Ikari et al. (2007), who reported that the friction coefficient of Ca-montmorillonite changes with water contents. Their friction coefficient for fully hydrated montmorillonite is close but slightly higher than our data at the highest relative humidity of ~ 90%. Behnsen and Faulkner (2013) carried out frictional experiments on Ca-exchanged montmorillonite under water-saturated conditions at effective normal stress of 10–100 MPa, yielding 0.11 values by a liner fitting curve; however, because of the jacket strength, the frictional coefficient might be overestimated at low effective normal stress.

We found that Na-montmorillonite has a higher friction coefficient than Ca-montmorillonite at a given relative humidity. This result is consistent with the findings for cation-exchanged montmorillonite obtained by Behnsen and Faulkner (2013) under deionized-water-saturated conditions. Although Shimamoto and Logan (1981) observed that the frictional strength of Na-montmorillonite is higher than that of Ca-montmorillonite, their Na- and Ca-montmorillonite samples had different origins and were not cation-exchanged. Bird (1984) studied the frictional strength of both cation-exchanged Na- and Ca-montmorillonite and showed that Na-montmorillonite is stronger than Ca-montmorillonite at two water layer, but is similar or weaker at other hydration state.

Effect of humidity and interlayer cations on the frictional strength of montmorillonite

The planar shape of montmorillonite means that frictional sliding is mainly accommodated via shear resistance on the (001) basal plane. Moore and Lockner (2004) suggested that the (001) bonding strength is a primary factor controlling frictional coefficient of the sheet silicates; however, recent experiments by Behnsen and Faulkner (2012) found the friction coefficient of various clay minerals were deviated significantly from the value predicted from the electrostatic separation energy. Sakuma and Suehara (2015) calculated interlayer bonding energy using the first-principles based density functional theory without using the empirical approximation of charge distributions in minerals, and they showed that there is no clear correlation with the frictional strength for layered minerals. Experiments using a single crystal of muscovite showed a markedly lower shear resistance than those using powder sample, suggested that the sliding does not necessarily occur only on the basal plane in the clay-bearing gouges (Kawai et al. 2015). These data indicate that the friction coefficient of layered silicate are not simply controlled by interlayer bonding energy of the (001) basal plane.

The type of interlayer cation influences the strength of montmorillonite, and using cation-exchanged samples is the best method for evaluating such effect. Our experimental results for cation-exchanged montmorillonite reveal that the frictional strength of Na-montmorillonite is higher than that of Ca-montmorillonite at a given relative humidity (Fig. 6). These characteristics are consistent with water-saturated experiments reported by Behnsen and Faulkner (2013), where Na-montmorillonite showed a slightly higher frictional strength at normal stress ranging from 10 to 100 MPa. This could be explained by the different swelling behavior of Ca- and Na-montmorillonites, where Na-montmorillonite has a smaller basal spacing at low to moderate relative humidity (e.g., Mooney et al. 1952). A molecular dynamics simulation has also suggested that interlayer spacing and water content of Na-montmorillonite are significantly lower than those of Ca-montmorillonite at relative humidity ranging from 20 to 80% (Teich-McGoldrick et al. 2015). Because Na-montmorillonite swells more than Ca-montmorillonite at high relative humidity, the difference in frictional strength between Na-montmorillonite and Ca-montmorillonite becomes small, µ = 0.04–0.06 at relative humidity of ~ 90% (Fig. 6). The interlayer cation species also affect the swelling behavior of not only the interlayer space, but also inter-particle space. Salles et al. (2010) calculated the amount of interlayer and inter-particle water for cation-exchanged montmorillonites, suggesting that the amount of inter-particle (mesopore) water in Ca-montmorillonite is smaller than that in Na-montmorillonite at a given relative humidity. Although the study of Salles et al. (2010) was based on experimental data obtained under ambient conditions, it implies that the interlayer cation species affect frictional strength through changing the inter-particle water content.

We showed that friction coefficient of both Ca- and Na-montmorillonite decreases systematically with increasing relative humidity (Fig. 3). A large difference in wet and dry frictional strength has been reported by previous experiments using various types of montmorillonite (Summers and Byerlee 1977b; Bird 1984; Morrow et al. 1992, 2000, 2017; Brown et al. 2003; Faulkner et al. 2011; Behnsen and Faulkner 2012; Bullock et al. 2015). Since the basal plane spacing change with relative humidity (e.g., Mooney et al. 1952), these changes attribute to the variation of friction coefficient of montmorillonites through reducing the interlayer bonding energy. Although the friction coefficient of montmorillonite decreases systematically with increasing relative humidity, the change in the friction coefficient of Ca-montmorillonite is relatively small. This may be due to a smaller increasing rate of swelling in Ca-montmorillonite at high relative humidity than low to moderate relative humidity (Morodome and Kawamura 2009). Another explanation of water weakening of montmorillonite is that water films on montmorillonite crystal surface (e.g., Moore and Lockner 2007). Renard and Ortoleva (1997) calculated the thickness of a water film adsorbed on a mineral surface and showed that the thickness of the water film decreases with increasing effective normal stress. However, our experiments were conducted at a constant normal stress (10 MPa); consequently, the water weakening found in this study is most likely due to the absorbed interlayer water.

These results combined with previous experiments indicate that frictional strength of montmorillonite is largely influenced by the hydration state. Although the natural fault zones can be nearly saturated by aqueous fluids, burial cementation and/or excess pore fluid pressure results in changing effective pressure, hence different hydration state (e.g., Bird 1984). So that the frictional behaviors of montmorillonite-bearing fault zones are sensitive to these physicochemical environments.

Conclusions

We have investigated the effects of humidity and interlayer cations on the frictional strength of montmorillonite using cation-exchanged samples and frictional experiments under controlled humidity conditions. Our results indicate that the friction coefficients for both Na- and Ca-montmorillonite decrease systematically with increasing relative humidity and that Na-montmorillonite is stronger than Ca-montmorillonite at a given relative humidity, suggesting that hydration state and interlayer cations influence frictional strength. Future research should investigate other frictional properties (e.g., velocity dependence of friction and frictional healing) of various types of cation-exchanged montmorillonite under different humidity conditions, to better understand natural fault behavior.

Abbreviations

- RH:

-

relative humidity

- T:

-

temperature

References

Behnsen J, Faulkner DR (2012) The effect of mineralogy and effective normal stress on frictional strength of sheet silicates. J Struct Geol 42:49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2012.06.015

Behnsen J, Faulkner DR (2013) Permeability and frictional strength of cation-exchanged montmorillonite. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 118:2788–2798. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50226

Bird P (1984) Hydration-phase diagrams and friction of montmorillonite under laboratory and geologic conditions, with implications for shale compaction, slope stability, and strength of fault gouge. Tectonophysics 107:235–260

Brown KM, Kopf A, Underwood MB, Weinberger JL (2003) Compositional and fluid pressure controls on the state of stress on the Nankai subduction thrust: a weak plate boundary. Earth Planet Sci Lett 214:589–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00388-1

Bullock RJ, De Paola N, Holdsworth RE (2015) An experimental investigation into the role of phyllosilicate content on earthquake propagation during seismic slip in carbonate faults. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120:3187–3207. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB011914

Byerlee J (1978) Friction of rocks. Pure Appl Geophys 116:615–626

Carpenter BM, Ikari MJ, Marone C (2016) Laboratory observations of time-dependent frictional strengthening and stress relaxation in natural and synthetic fault gouges. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 121:1183–1201. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB012136

Colten-Bradley VA (1987) Role of pressure in smectite dehydration—effects on geopressure and smectite-to-illite transformation. Am Assoc Pet Geol Bull 71:1414–1427

Deng X, Underwood MB (2001) Abundance of smectite and the location of a plate-boundary fault, Barbados accretionary prism. Bull Geol Soc Am 113:495–507

Faulkner DR, Mitchell TM, Behnsen J, Hirose T, Shimamoto T (2011) Stuck in the mud? Earthquake nucleation and propagation through accretionary forearcs. Geophys Res Lett 38:L18303. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL048552

Fujita T, Sugita Y, Toida M (2011) Experimental studies on penetration of pulverized clay-based grout. J Energy Power Eng 5:419–427

Haines SH, Kaproth B, Marone C, Saffer D, van der Pluijm B (2013) Shear zones in clay-rich fault gouge: a laboratory study of fabric development and evolution. J Struct Geol 51:206–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2013.01.002

Ikari MJ, Saffer DM, Marone C (2007) Effect of hydration state on the frictional properties of montmorillonite-based fault gouge. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 112:B06423. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004748

Ito M, Okamoto M, Shibata M, Sasaki Y, Danbara T, Suzuki K, Watanabe T (1993) Mineral composition analysis of bentonite. PNC TN8430, Japan Atomic Energy Agency (in Japanese)

Kameda J, Shimizu M, Ujiie K, Hirose T, Ikari M, Mori J, Oohashi K, Kimura G (2015) Pelagic smectite as an important factor in tsunamigenic slip along the Japan Trench. Geology 43:155–158. https://doi.org/10.1130/G35948.1

Kawai K, Sakuma H, Katayama I, Tamura K (2015) Frictional characteristics of single and polycrystalline muscovite and influence of fluid chemistry. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120:6209–6218. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB012286

Kubo T, Katayama I (2015) Effect of temperature on the frictional behavior of smectite and illite. J Mineral Petrol Sci 110:293–299. https://doi.org/10.2465/jmps.150421

Kuo LW, Song SR, Yeh EC, Chen HF (2009) Clay mineral anomalies in the fault zone of the Chelungpu fault, Taiwan, and their implications. Geophys Res Lett 36:L18306. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL039269

Logan JM, Rauenzahn KA (1987) Frictional dependence of gouge mixtures of quartz and montmorillonite on velocity, composition and fabric. Tectonophysics 144:87–108

Lupini JF, Skinner AE, Vaughan PR (1981) The drained residual strength of cohesive soils. Géotechnique 31:181–213

Mooney RW, Keenan AG, Wood LA (1952) Adsorption of water vapor by montmorillonite. II. Effect of exchangeable ions and lattice swelling as measured by X-ray diffraction. J Am Chem Soc 74:1371–1374

Moore DE, Lockner DA (2004) Crystallographic controls on the frictional behavior of dry and water-saturated sheet structure minerals. J Geophys Res 109:B03401. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JB002582

Moore DE, Lockner DA (2007) Friction of the smectite clay montmorillonite. In: Dixon T, Moore C (eds) The seismogenic zone of subduction thrust faults. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 317–345

Morodome S, Kawamura K (2009) Swelling behavior of Na- and Ca-montmorillonite up to 150 °C by in situ X-ray diffraction experiments. Clays Clay Miner 57:150–160. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.2009.0570202

Morrow C, Radney B, Byerlee J (1992) Frictional strength and the effective pressure law of montmorillonite and illite clays. In: Evans B, Wong T-F (eds) Fault mechanics and transport properties of rocks. Academic Press, New York, pp 69–88

Morrow CA, Moore DE, Lockner DA (2000) The effect of mineral bond strength and adsorbed water on fault gouge frictional strength. Geophys Res Lett 27:815–818. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GL008401

Morrow CA, Moore DE, Lockner DA (2017) Frictional strength of wet and dry montmorillonite. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JB013658

Müller-Vonmoos M, Løken T (1989) The shearing behaviour of clays. Appl Clay Sci 4:125–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-1317(89)90004-5

Noda H, Shimamoto T (2009) Constitutive properties of clayey fault gouge from the Hanaore fault zone, southwest Japan. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 114:B04409. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB005683

Ohtani T, Fujimoto K, Ito H, Tanaka H, Tomida N, Higuchi T (2000) Fault rocks and past to recent fluid characteristics from the borehole survey of the Nojima fault ruptured in the 1995 Kobe earthquake, southwest Japan. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 105:16161–16171. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JB900086

Oohashi K, Hirose T, Takahashi M, Tanikawa W (2015) Dynamic weakening of smectite-bearing faults at intermediate velocities: implications for subduction zone earthquakes. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120:1572–1586. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB011881

Renard F, Ortoleva P (1997) Water films at grain-grain contacts: Debye–Hückel, osmotic model of stress, salinity, and mineralogy dependence. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:1963–1970

Saffer DM, Marone C (2003) Comparison of smectite- and illite-rich gouge frictional properties: application to the updip limit of the seismogenic zone along subduction megathrusts. Earth Planet Sci Lett 215:219–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00424-2

Saffer DM, Frye KM, Marone C, Mair K (2001) Laboratory results indicating complex and potentially unstable frictional behavior of smectite clay. Geophys Res Lett 28:2297–2300

Sakuma H, Suehara S (2015) Interlayer bonding energy of layered minerals: implication for the relationship with friction coefficient. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120:2212–2219. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB011900

Salles F, Bildstein O, Douillard JM, Jullien M, Raynal J, Van Damme H (2010) On the cation dependence of interlamellar and interparticular water and swelling in smectite clays. Langmuir 26:5028–5037. https://doi.org/10.1021/la1002868

Schleicher AM, Van Der Pluijm BA, Solum JG, Warr LN (2006) Origin and significance of clay-coated fractures in mudrock fragments of the SAFOD borehole (Parkfield, California). Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl026505

Shimamoto T, Logan JM (1981) Effects of simulated clay gouges on the sliding behavior of Tennessee sandston. Tectonophysics 75:243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(81)90276-6

Solum JG, Hickman SH, Lockner DA, Moore DE, Van Der Pluijm BA, Schleicher AM, Evans JP (2006) Mineralogical characterization of protolith and fault rocks from the SAFOD main hole. Geophys Res Lett 33:L21314. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027285

Summers R, Byerlee J (1977a) A note on the effect of fault gouge composition on the stability of frictional sliding. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 14:155–160

Summers R, Byerlee J (1977b) Summary of results of frictional sliding studies, at confining pressures up to 6.98 kb, in selected materials. In: U.S. Geological Survey Open File Rep

Takahashi M, Mizoguchi K, Kitamura K, Masuda K (2007) Effects of clay content on the frictional strength and fluid transport property of faults. J Geophys Res 112:B08206. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004678

Teich-McGoldrick SL, Greathouse JA, Jové-Colón CF, Cygan RT (2015) Swelling properties of montmorillonite and beidellite clay minerals from molecular simulation: comparison of temperature, interlayer cation, and charge location effects. J Phys Chem C 119:20880–20891

Tembe S, Lockner DA, Wong T-F (2010) Effect of clay content and mineralogy on frictional sliding behavior of simulated gouges: binary and ternary mixtures of quartz, illite, and montmorillonite. J Geophys Res 115:B03416. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JB006383

Tetens O (1930) Über einige meteorologische Begriffe. Z Geophys 6:297–309 (in German)

Underwood MB (2007) Sediment inputs to subduction zones why lithostratigraphy and clay mineralogy matter. In: Dixon T, Moore C (eds) The seismogenic zone of subduction thrust faults. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 42–85

Vrolijk P, Van Der Pluijm BA (1999) Clay gouge. J Struct Geol 21:1039–1048. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8141(99)00103-0

Wu FT (1978) Mineralogy and physical nature of clay gouge. Pure appl Geophys 116:655–689

Authors’ contributions

HT carried out experiments under technical and scientific advice on sample preparation by KT and HS, and on frictional experiments by IK. HT analyzed the experimental data and wrote the draft manuscript. HT and IK revised the draft through discussion with HS and KT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Katsuyuki Kawamura, Kenji Kawai and Tatsuro Kubo for discussions and technical advice for the experiments. We also thank Yasutaka Hayasaka, Kosuke Kimura, and Takuya Furuhashi for technical assistance with XRF analyses, and Shoji Morodome for sample information. Comments from Matt Ikari and three anonymous reviewers largely improved the manuscript. We appreciate Toyo Koatsu Co. Ltd. who helped to develop the humidity control system in our friction testing machine. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15H02147 and JP16H06476 in Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Science of Slow Earthquakes”.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data presented in this study are available by contacting the corresponding author.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15H02147 and JP16H06476 in Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Science of Slow Earthquakes”.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tetsuka, H., Katayama, I., Sakuma, H. et al. Effects of humidity and interlayer cations on the frictional strength of montmorillonite. Earth Planets Space 70, 56 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-018-0829-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-018-0829-1