Abstract

Spatial and temporal variations in inland crustal stress prior to the 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku earthquake are investigated using focal mechanism solutions for shallow seismicity in Iwaki City, Japan. The multiple inverse method of stress tensor inversion detected two normal-faulting stress states that dominate in different regions. The stress field around Iwaki City changed from a NNW–SSE-trending triaxial extensional stress (stress regime A) to a NW–SE-trending axial tension (stress regime B) between 2005 and 2008. These stress changes may be the result of accumulated extensional stress associated with co- and post-seismic deformation due to the M7 class earthquakes. In this study we suggest that the stress state around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake may have been extensional with a low differential stress. High pore pressure is required to cause earthquakes under such small differential stresses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

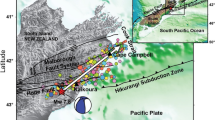

After the Mw 9.0 earthquake that occurred on March 11, 2011, offshore Tohoku, Japan (hereafter, the 2011 Tohoku earthquake; e.g., Ozawa et al. 2011; Simons et al. 2011), many crustal earthquakes were induced in inland regions of northeastern Japan (e.g., Hirose et al. 2011; Yoshida et al. 2012). A remarkable phenomenon of the induced seismicity was a sudden increase in shallow normal faulting along the Pacific coast of northeastern Japan, most notably in the Fukushima and Ibaraki prefectures (Fig. 1). A Mw 6.6 earthquake occurred on April 11, 2011, in Iwaki City, Fukushima Prefecture (hereafter, the 2011 Iwaki earthquake; Fig. 1), just 1 month after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. The focal mechanism of this earthquake is believed to correspond to normal faulting with a NE–SW-oriented T axis (Fig. 1, adapted from Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) catalog data; see e.g., Lin et al. 2013; Otsubo et al. 2013; Toda and Tsutsumi 2013), despite the fact that crustal normal faulting in response to a trench-type earthquake is very rare (e.g., Farías et al. 2011).

Lower-hemisphere, equal-area stereographic focal mechanism solutions of earthquakes prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (from Imanishi et al. 2012). Colors of focal spheres indicate depths of hypocenters. Numbered focal mechanisms corresponding to solid circles are those used in this study; seismic events plotted with open circles were not used. The focal mechanism for the 2011 Iwaki earthquake is from the JMA catalog. Orange circles show seismic events shallower than 15 km based on JMA catalog depths from March 11, 2011, to December 31, 2011. The epicenters of events 4 and 11 are deeper than 15 km. The dashed circle indicates the approximate boundaries of the low-velocity zone resolved by Kato et al. (2013). Blue lines show the active faults (Research Group for Active Faults in Japan 1991)

Earthquake focal mechanisms are thought to be the most effective means of identifying crustal stress (e.g., Michael 1984), because they constrain the stress field at depths where earthquakes occur. Imanishi et al. (2012) reported a normal-faulting stress regime around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake by applying the stress tensor inversion method of Michael (1984) to small-magnitude earthquakes. They concluded that the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, in combination with a preexisting normal-faulting stress regime, triggered a normal-faulting earthquake sequence. However, the estimated stress tensor did not account for all focal mechanisms, suggesting the existence of stress heterogeneity.

The aim of this study is to explore spatial and temporal variations in crustal stress around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. We apply the multiple inverse method (Otsubo et al. 2008) to the earthquake focal mechanisms of Imanishi et al. (2012) and show that two normal-faulting stress states prevailed in different regions. We examine the tectonic background of the spatial and temporal variations in stress and discuss the stress level in the background of the region of the study area.

Methods

Imanishi et al. (2012) computed the focal mechanisms of 26 small shallow earthquakes (Mj ≤ 3.2, depth < 20 km) around Iwaki City that occurred between 2003 and 2010. We applied the stress tensor inversion to 12 earthquakes (Imanishi et al. 2012; Additional file 1: Table S1) with normal-faulting and strike-slip faulting mechanisms located within the source region of the normal-faulting earthquake sequence. Following Imanishi et al. (2011), we evaluated focal mechanism uncertainties for each event from the average of their Kagan angles (Kagan 1991), where uncertainties are measured between the best fitting solution and each solution whose residual is less than 1.1 × the minimum residual. Most events show normal faulting with T axes that trend WNW–ESE to NNW–SSE (Fig. 1). Imanishi et al. (2012) applied the method of Michael (1984) to these 12 focal mechanisms and obtained a normal-faulting stress regime with a minimum principal stress axis trending NW–SE and a stress ratio Φ = (σ2 − σ3)/(σ1 − σ3) = 0.6–0.7, where σ1, σ2, and σ3 are the maximum, intermediate, and minimum principal stress axes, respectively. However, some focal mechanisms yielded different stress regimes, which may suggest that the assumption of a homogeneous stress state is inappropriate for these data.

In contrast to conventional stress tensor inversion methods (e.g., Gephart and Forsyth 1984; Michael 1984), the multiple inverse method (MIM; Otsubo et al. 2008) is able to separate and isolate stresses from complex focal mechanism data based on a resampling technique without prior information. Significant stresses were categorized into clusters of stress tensors using the resampling technique of Otsubo et al. (2008), which employs k-means clustering, similar to Otsubo et al. (2006), to recognize clusters of stress tensors. For the ith cluster, the 95% confidence interval (CI (i)95 ) is calculated using CI (i)95 = σ(i) mean ± 1.96 × SE(i), where σ(i) mean is the mean of the contributing stresses (i.e., the cluster center) and SE(i) is the standard error about the mean. SE(i) itself is defined by the equation SE(i) = S(i)/(N(i))1/2, where S(i) is the standard deviation of the ith cluster and N(i) is the number of stress observations contributing to S(i). The standard deviation is calculated from the distance between the cluster center and each stress tensor assigned to the same cluster. We employed the angular stress distance described by Yamaji and Sato (2006) to calculate distances in this study.

When we applied MIM to the 12 focal mechanisms derived by Imanishi et al. (2012), we employed the combination number kf = 5 and the enhance factor e = 8, following Otsubo et al. (2008, 2013). A value of 4 or 5 is usually assigned to kf because the stress tensor inversion is an even-determined problem for four observations and is overdetermined for five (Yamaji 2000; Otsubo et al. 2008). The enhance factor e is a parameter used to attenuate the effects of noisy data in the solution space (Yamaji 2000). The default value of e is 8; MIM nominally accepts values in the range 0 ≤ e ≤ 99.

Results

We applied MIM to the data set of Imanishi et al. (2012) and detected two normal-faulting stress regimes, labeled A and B in Fig. 2. For stress regime A, σ1 and σ3 are orientated at 331°/75° and 140°/15°, respectively, and the stress ratio Φ = 0.54 ± 0.18 (Fig. 2b, c). Thus, regime A corresponds to a NNW–SSE-trending triaxial extensional stress. The second solution, regime B, shows σ1 and σ3 orientations of 147°/87° and 299°/3°, respectively, with a stress ratio Φ = 0.84 ± 0.10 (Fig. 2b, c), which corresponds to NW–SE-trending axial tension (σ1 = σv ≈ σ2 >> σ3). The angular stress distance between A and B, defined as the dissimilarity between two stresses (Yamaji and Sato 2006), is ~ 39°, suggesting that the stresses are significantly different from each other (Nemcok and Lisle 1995). The σ3 orientations of the stresses do not overlap at the 95% confidence level for the means and standard deviations of the k-means clusters (Fig. 2). The solution of Imanishi et al. (2012), using the method of Michael (1984) and shown by crosses in Fig. 2b, diverges from regime B by ~ 27° and from A by ~ 31°, suggesting a slightly better match to B.

Crustal stresses around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. a Lower-hemisphere, equal-area stereographic projections showing the results of the multiple inverse method (MIM; Otsubo et al. 2008) applied to selected events in Fig. 1 (solid circles). The multiple inverse method was applied with the combination number k f = 5 and the enhance factor e = 8 (see Yamaji (2000) for explanations of these parameters). The left and right stereograms show the results for the σ1 and σ3 axes, respectively. The colors of the symbols correspond to stress ratios. b Results of k-means clustering (after Otsubo et al. 2006) applied to the data in a. Black diamonds indicate the axes of the optimal stresses. White diamonds indicate the axes of the stress detected from the focal mechanism data earthquakes that occurred between March 12, 2011, and April 11, 2011 (Otsubo et al. 2013). Crosses (+) indicate the axes of the normal faulting stress around Iwaki City, as calculated by Imanishi et al. (2012) using the method of Michael (1984). Dashed circles show 95% confidence intervals. Triangles outside stereograms indicate the orientations of co- and post-seismic displacements of the M7 class earthquakes around Iwaki City (Suito et al. 2011). c Histogram of stress ratios of stress tensors calculated by the MIM technique. Diamond symbols indicate calculated mean stress ratios

The Wallace–Bott hypothesis (Wallace 1951; Bott 1959) states that an earthquake’s slip vector is parallel to the resolved shear stress on the fault. Based on this hypothesis, we assume that a stress is compatible with a fault slip direction if the misfit angle between the slip direction predicted by the stress and the observed slip direction on the same fault plane is sufficiently small. In this study, we adopt the approach of Otsubo et al. (2008, 2013) for the analysis of stress and associated focal mechanisms in the Iwaki City region. The spatial and temporal changes in stress can be identified by relating observed slip directions from focal mechanisms to a single stress solution (Otsubo et al. 2008, 2013). The threshold of the misfit angle was determined here based on the uncertainties of the strike, dip, and rake (Gephart and Forsyth 1984; Michael 1991). When the misfit angles are smaller than the uncertainties of the stress and focal mechanism solutions, the observed slip directions agree with theoretical values to within the estimated uncertainties.

Figure 3 shows the computed misfit angle for each focal mechanism with respect to A and B, with only the smaller angle for each pair of nodal planes shown. If we assume that a stress with a misfit angle of less than 30° is compatible with a datum (e.g., Gephart and Forsyth 1984; Michael 1991), either or both stresses are able to explain the source of 10 of the 12 events (Fig. 3). The stress for the two earthquakes with larger misfit angles (nos. 4 and 11) is unclear because the stress tensor inversion is underdetermined for a value of two earthquakes (Yamaji 2000; Otsubo et al. 2008). These earthquakes are located deeper than 15 km, which is below both the focal depth of the 2011 Iwaki earthquake (~ 6 km) and the floor of the inland seismicity that was experienced after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (~ 10 km) (Fig. 1; see also Imanishi et al. 2012); thus, we do not discuss them further.

Misfit angles of the 12 highlighted earthquakes in Fig. 1 for crustal stresses around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Red and blue bars indicate the misfit angles for stresses A and B, respectively. A stress with a misfit angle less than 30° (shaded region) is considered compatible with a focal mechanism determination (Gephart and Forsyth 1984; Michael 1991). Triangles indicate earthquakes compatible with either stress regime A (red triangles) or stress regime B (blue triangles) based on the approach of Otsubo et al. (2008, 2013). This approach ensures a robust result when based on the misfits of only four earthquakes

Discussion

Using the focal mechanisms of Imanishi et al. (2012), MIM reveals two normal-faulting stress states around Iwaki City before the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (Fig. 2). In this study, we discuss the temporal and spatial stress changes around Iwaki City to explain the stress heterogeneity.

Temporal and spatial stress changes around Iwaki City

We attribute the variations in the stress field to temporal variations. Stress regime A can be seen to account for all the focal mechanisms derived from earthquakes that occurred before 2005. This implies that only stress regime A should be used as an appropriate solution before 2005 (Fig. 3). In contrast, stress regime B can be seen to account for all the focal mechanisms, except for no. 11, derived from earthquakes occurring after 2008 (Fig. 3). In the intervening period between 2005 and 2008, derived focal mechanisms can be related to both stress regimes A and B. Hence, one possible explanation of the stress heterogeneity is that the stress field around Iwaki City temporally changed from a NNW–SSE-trending triaxial extensional stress (regime A) to a NW–SE-trending axial tension (regime B), with the transition between the two occurring from 2005 to 2008. Hence, we define stress period I from 2003 to 2005 and stress period II from 2008 to 2010 (Fig. 3).

Next, we consider the dynamics for the stress changes around Iwaki City. The σ3 orientation of stress regime B is subparallel to the orientations of the co- and post-seismic displacements of large earthquakes (Mw ~ 7) that occurred during the period 2005–2010 (Fig. 2b; Suito et al. 2011). The post-seismic deformation determined from continuous GNSS monitoring reveals that the seismic moments released by transient slip following the M7 class earthquakes are much larger than the seismic moment estimates for the earthquakes themselves (Suito et al. 2011). Stress regime B may therefore be the result of accumulated extensional stress associated with co- and post-seismic deformation due to the M7 class earthquakes, which occur more frequently than M9 class earthquakes.

We focus on the location of the epicenter of the earthquakes to explain the stress heterogeneity around Iwaki City. Stress regime A accommodates all focal mechanisms derived from earthquakes in the western part of the study area around 140.8°E, except for no. 11. This implies that stress regime A is the most appropriate solution for this region (Fig. 4). On the other hand, stress regime B encompasses all focal mechanisms in the region around 141.0°E (Fig. 4). In the area between the two regions, the computed focal mechanisms could be related to either regime (Fig. 4). Hence, we infer that a series of M7 class earthquakes altered the stress regime only in the east of the study area.

Spatial variations in crustal stresses around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Numbered circles are earthquakes used in this study. The star indicates the epicenter of the 2011 Iwaki earthquake. The two earthquakes (nos. 4 and 11) located deeper than 15 km are not discussed further in this study, as we focus on shallow crustal stress

Estimation of differential stress around Iwaki City

Figure 5 shows the GNSS time series of the NW–SE component at sites near Iwaki City together with the occurrence times of five M7 interplate earthquakes. The time series show a deviation from a steady westward movement after the 2008 Mj 7.0 Ibaraki-ken Oki earthquake (label B). The timing of the transition toward eastward motion appears to correlate with the period during which stress regime B was dominant. The observation supports the hypothesis that the inferred change in stress field over time was due to extension associated with the co- and post-seismic deformation from the M7 class earthquakes.

Relationship between the two stress periods prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and co- and post-seismic deformation of the M7 class earthquakes around Iwaki City. The relative difference between the NW–SE components of the GNSS time series at the two sites among the eight sites (a–h) near Iwaki City is plotted for the period from January 1, 2002, to March 1, 2011. Positive increases correspond to eastward movement. The eight stations for which we analyzed time series of GNSS data are: (a) 950,205; (b) 950,208; (c) 020,944; (d) 940,041; (e) 950,211; (f) 970,800; (g) 020,945; (h) 020,946; (i) 950,212; (j) 950,214. Five M7 class trench-type earthquakes with large post-seismic slips that occurred along the Japan Trench (Suito et al. 2011) are also marked: (A) August 16, 2005, Miyagi-ken Oki earthquake (Mj 7.2); (B) May 8, 2008, Ibaraki-ken Oki earthquake (Mj 7.0); (C) July 19, 2008, Fukushima-ken Oki earthquake (Mj 6.9); (D) March 14, 2010, Fukushima-ken Oki earthquake (Mj 6.7); and (E) March 9, 2011, Sanriku-Oki earthquake (Mj 7.3). Diamonds and stars on the inset map show the stations for the time series used in this study and epicenters of the five M7 class trench-type earthquakes, respectively. The rapid change in a–b (point *) is due to the maintenance of site 940,041. We do not discuss the rapid change in c–d (point †) in this study

We compared the stress changes caused by the co- and post-seismic deformation with the extensional stresses in stress periods I and II. The direction of extensional stresses induced by the co- and post-seismic deformation is almost parallel to the orientation of the σ3 axes, while it is perpendicular to the orientations of the σ1 and σ2 axes (Fig. 2b). Because σ1 is the overburden pressure, σ1 is almost constant during the co- and post-seismic deformation. Hence, the extensional stress induced by the co- and post-seismic deformation should only affect the magnitude of σ3 rather than those of σ1 and σ2, and in order for the stress ratio to change from 0.54 (± 0.18) to 0.84 (± 0.10), σ3 must decrease. Here, the reduction in the magnitude of σ3 corresponds to a build-up of extensional stress.

The magnitude of the differential stress in the study area is estimated based on the temporal change in the stress field (Fig. 6). For convenience, in the following discussion, we define σ A1 (σ B1 ), σ A2 (σ B2 ), and σ A3 (σ B3 ) as the maximum, intermediate, and minimum compressive principal stresses for stress A (and B), respectively. The differential stress for stress A (B) can be expressed by ΔσA = σ A 1 − σ A3 (ΔσB = σ B 1 − σ B3 ). From the change in the stress ratio from 0.54 (± 0.18) to 0.84 (± 0.10), we obtain the following relationships: σ B3 − σ A 3 ~ 0.09 − 9.03ΔσA and ΔσB ~ 1.08 – 10.03ΔσA (Fig. 6). The former relationship indicates that the extensional stress induced by the co- and post-seismic deformation is approximately 0.1 to 9 times as large as the differential stress for stress A. The latter relationship signifies that the extensional differential stress increases by a factor of almost 1.1 to 10 from stress A to stress B. Based on the amount of displacement from the co- and post-seismic deformation (~ 1–3 cm; Fig. 5), the resulting strain is estimated to be ~ 3 × 10−7 to 2 × 10−6 for the NW–SE component between the two sites near Iwaki City. Assuming that the crust is elastic with a Young’s modulus of 32 GPa, the induced stress, σ B3 − σ A3 , is estimated between 0.9 × 10−2 and 6.4 × 10−2 MPa. Inserting this estimated value into the relationships derived above, we obtain differential stresses for stress A, ΔσA, and stress B, ΔσB, of approximately 1.00 × 10−3 to 7.11 × 10−1 and 1.10 × 10−3 to 7.13 MPa, respectively. Hence, we propose that the differential stress is less than the order of 1 MPa around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

Mohr circle representations of the state of stress for stress A (upper plot) and stress B (lower plot) for the extension associated with the co- and post-seismic deformations of the M7 class earthquakes. ρ is density, g is gravitational acceleration, z is depth, and ΔσA and ΔσB show the differential stress for stresses A and B, respectively

Background of the low differential stress around Iwaki City

We consider the generation of the 2011 Iwaki earthquake in the context of the low differential stress in the study area. We showed the stress heterogeneity around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake as the spatial or temporal stress changes. In this study, we could not identify a possible explanation of the stress heterogeneity. In both cases, we suggest that the stress state around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake might have been extensional with a low differential stress. A low differential stress prior to the 2011 Iwaki earthquake was reported by Yoshida et al. (2015), who estimated differential stress magnitudes ~100–101 MPa by comparing the stress orientations in the post-Iwaki earthquake period with static stress changes due to the Iwaki earthquake and three nearby M5 class earthquakes. Tomographic studies have imaged low-velocity anomalies beneath the hypocenter of the 2011 Iwaki earthquake (Fig. 1; see also Kato et al. 2013), which may correspond to zones of high pore-fluid pressure. Zhao (2015) showed that a low-velocity zone is visible in the lower crust and mantle wedge, and that it extends beneath the hypocenter of the 2011 Iwaki earthquake, down to the subducting Pacific slab. The discharge of a large amount of thermal water after the 2011 Iwaki earthquake (Sato et al. 2011; Kazahaya et al. 2013) indicates that earthquakes in this region promote the upwelling of deep groundwater. The earthquakes themselves may be triggered by a decrease in effective normal stress and fault strength due to the increased pore-fluid pressure (e.g., Sibson 1990; Micklethwaite and Cox 2006; Terakawa et al. 2013). By examining the fault failure of the 2011 Iwaki earthquake with respect to the change in the state of stress in the Iwaki area produced by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, Miyakawa and Otsubo (2015) showed that excess fluid pressure is required to explain the 2011 Iwaki earthquake. Therefore, we infer that high pore-fluid pressure could enable the generation of earthquakes under conditions of low differential stress (Sibson 1992).

Conclusions

An investigation of spatial and temporal changes in extensional stress in the inter-seismic period before the 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku earthquake revealed that the pre-Tohoku stress state around Iwaki City was significantly heterogeneous. Our findings support the inference that the stress state around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake was extensional with a low differential stress. The differential stress of the normal-faulting stress regime increased after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

The multiple inverse method (MIM) of stress inversion resolves statistically significant stress heterogeneities in the study area. The MIM is capable of detecting stress heterogeneities that cannot be detected using more conventional stress tensor inversion methods. The application of the MIM to other study areas in the future may provide an important monitoring tool for evaluating stress change.

Abbreviations

- JMA:

-

Japan Meteorological Agency

- GNSS:

-

global navigation satellite system

- MIM:

-

multiple inverse method

References

Bott MHP (1959) The mechanics of oblique slip faulting. Geol Mag 96(2):109–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800059987

Farías M, Comte D, Roecker S, Carrizo D, Pardo M (2011) Crustal extensional faulting triggered by the 2010 Chilean earthquake: The Pichilemu Seismic Sequence. Tectonics 30:6010. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011tc002888

Gephart JW, Forsyth DW (1984) An improved method for determining the regional stress tensor using earthquake focal mechanism data: application to the San Fernando Earthquake Sequence. J Geophys Res 89(B11):9305–9320. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB089iB11p09305

Hirose F, Miyaoka K, Hashimoto N, Yamazaki T, Nakamura M (2011) Outline of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake (Mw9.0) Seismicity: foreshocks, mainshock, aftershocks, and induced activity. Earth Planet Space 63:513–518. https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.05.019

Imanishi K, Kuwahara Y, Takeda T, Mizuno T, Ito H, Ito K, Wada H, Haryu Y (2011) Depth-dependent stress field in and around the Atotsugawa fault, central Japan, deduced from microearthquake focal mechanisms: evidence for localized aseismic deformation in the downward extension of the fault. J Geophys Res 116:B01305. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JB007900

Imanishi K, Ando R, Kuwahara Y (2012) Unusual shallow normal-faulting earthquake sequence in compressional northeast Japan activated after the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake. Geophys Res Lett 39(9):L09306. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051491

Kagan Y (1991) 3-D rotation of double-couple earthquake sources. Geophys J Int 106(3):709–716

Kato A, Igarashi T, Obara K, Sakai S, Takeda T, Saiga A, Iidaka T, Iwasaki T, Hirata N, Goto K, Miyamachi H, Matsushima T, Kubo A, Katao H, Yamanaka Y, Terakawa T, Nakamichi H, Okuda T, Horikawa S, Tsumura N, Umino N, Okada T, Kosuga M, Takahashi H, Yamada T (2013) Imaging the source regions of normal faulting sequences induced by the 2011 M9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophys Res Lett 40(2):273–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50104

Kazahaya K, Sato T, Takahashi M, Tosaki Y, Morikawa N, Takahashi H, Horiguchi K (2013) Genesis of thermal water related to Iwaki-Nairiku earthquake. In: Japan Geoscience Union Meeting, Makuhari Messe, Chiba, 19–24 May 2013. (in Japanese with English abstract)

Lin A, Toda S, Rao G, Tsuchihashi S, Yan B (2013) Structural analysis of coseismic normal fault zones of the 2011 Mw 6.6 Fukushima earthquake, northeast Japan. Bull Seismol Soc Am 103:1603–1613. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120120111

Michael A (1984) Determination of stress from slip data: Faults and folds. J Geophys Res 89(B13):11517–11526. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB089iB13p11517

Michael A (1991) Spatial variations in stress within the 1987 Whittier Narrows, California, aftershock sequence: new technique and results. J Geophys Res 96:6303–6319

Micklethwaite S, Cox S (2006) Progressive fault triggering and fluid flow in aftershock domains: Examples from mineralized Archaean fault systems. Earth Planet Sci Lett 250:318–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.07.050

Miyakawa A, Otsubo M (2015) Effect of a change in the state of stress on inland fault activity during the Mw 6.6 Iwaki earthquake resulting from the Mw 9.0 2011 Tohoku earthquake, Japan. Tectonophysics 661:112–120

Nemcok M, Lisle R (1995) A stress inversion procedure for polyphase fault/slip data sets. J Struct Geol 17(10):1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8141(95)00040-K

Otsubo M, Sato K, Yamaji A (2006) Computerized identification of stress tensors determined from heterogeneous fault-slip data by combining the multiple inverse method and k-means clustering. J Struct Geol 28(6):991–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2006.03.008

Otsubo M, Yamaji A, Kubo A (2008) Determination of stresses from heterogeneous focal mechanism data: an adaptation of the multiple inverse method. Tectonophysics 457(3–4):150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2008.06.012

Otsubo M, Shigematsu N, Imanishi K, Ando R, Takahashi M, Azuma T (2013) Temporal slip change based on curved slickenlines on fault scarps along Itozawa fault caused by 2011 Iwaki earthquake, northeast Japan. Tectonophysics 608:970–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2013.07.022

Ozawa S, Nishimura T, Suito H, Kobayashi T, Tobita M, Imakiire T (2011) Coseismic and postseismic slip of the 2011 magnitude-9 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Nature 475:373–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10227

Research Group for Active Faults in Japan (1991) Active faults in Japan, sheet maps and inventories, revised edn. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, p 437

Sato T, Kazahaya K, Yasuhara M, Itoh J, Takahashi HA, Morikawa N, Takahashi M, Inamura A, Handa H, Matsumoto N (2011) Hydrological changes due to the M7.0 earthquake at Iwaki, Fukushima induced by the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake, Japan. In: American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting. The Moscone Center, San Francisco, 5–9 December 2011

Sibson R (1990) Rupture nucleation on unfavorably oriented faults. Bull Seismol Soc Am 80:1580–1604

Sibson R (1992) Implications of fault-valve behavior for rupture nucleation and recurrence. Tectonophysics 211(1–4):283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(92)90065-E

Simons M, Minson SE, Sladen A, Ortega F, Jiang J, Owen SE, Meng L, Ampuero J-P, Wei S, Chu R, Helmberger DV, Kanamori H, Hetland E, Moore AW, Webb FH (2011) The 2011 magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake: mosaicking the megathrust from seconds to centuries. Science 332(6036):1421–1425. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1206731

Suito H, Nishimura T, Tobita M, Imakiire T, Ozawa S (2011) Interplate fault slip along the Japan Trench before the occurrence of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake as inferred from GPS data. Earth Planet Space 63:615–619. https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.06.053

Terakawa T, Hashimoto C, Matsu’ura M (2013) Changes in seismic activity following the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake: effects of pore fluid pressure. Earth Planet Sci Lett 365:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.01.017

Toda S, Tsutsumi H (2013) Simultaneous reactivation of two subparallel, inland normal faults during the Mw 6.6 11 April 2011 Iwaki Earthquake triggered by the Mw 9.0 Tohoku-oki, Japan, Earthquake. Bull Seismol Soc Am 103:1584–1602

Wallace R (1951) Geometry of shearing stress and relation to faulting. J Geol 59(2):118–130

Wessel P, Smith W (1998) New, improved version of the Generic Mapping Tools released. EOS Trans AGU 79(47):579. https://doi.org/10.1029/98EO00426

Yamaji A (2000) The multiple inverse method applied to meso-scale faults in mid-Quaternary fore-arc sediments near the triple junction off central Japan. J Struct Geol 22(4):429–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8141(99)00162-5

Yamaji A, Sato K (2006) Distances for the solutions of stress tensor inversion in relation to misfit angles that accompany the solutions. Geophys J Int 167(2):933–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.03188.x

Yoshida K, Hasegawa A, Okada T, Iinuma T, Ito Y, Asano Y (2012) Stress before and after the 2011 Great Tohoku-Oki earthquake and induced earthquakes in inland areas of eastern Japan. Geophys Res Lett 39:L03302. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049729

Yoshida K, Hasegawa A, Okada T (2015) Spatially heterogeneous stress field in the source area of the 2011 Mw 6.6 Fukushima-Hamadori earthquake, NE Japan, probably caused by static stress change. Geophys J Int 201(2):1062–1071. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggv068

Zhao D (2015) The 2011 Tohoku earthquake (Mw 9.0) sequence and subduction dynamics in Western Pacific and East Asia. J Asian Earth Sci 98:26–49

Authors’ contributions

MO led and designed the research and drafted the manuscript. MO carried out the stress tensor inversion analysis, drafted the figures, and contributed to assessing the results. AM and KI contributed to the discussion of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for suggestions that led to improvements in the manuscript. We thank Dr. T. Nishimura for discussions on GNSS data, and Dr. J. Hardebeck for fruitful discussions. This study was supported by MEXT KAKENHI (number 26109003). Some of the figures were generated using Generic Mapping Tools (GMT; Wessel and Smith Wessel and Smith 1998).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Seismic data are available from the authors upon request.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Fault slip data set obtained from focal mechanisms of earthquakes determined by Imanishi et al. (2012) around Iwaki City prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Otsubo, M., Miyakawa, A. & Imanishi, K. Normal-faulting stress state associated with low differential stress in an overriding plate in northeast Japan prior to the 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku earthquake. Earth Planets Space 70, 51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-018-0813-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-018-0813-9