Abstract

Background

Traffic-related fatalities are a leading cause of premature death worldwide. According to the 2012 report the Global Burden of Disease 2010, traffic injuries ranked 8th as a cause of death in 2010, compared to 10th in 1990. Saudi Arabia is estimated to have an overall traffic fatality rate more than double that of the U.S., but it is unknown whether mortality differences also exist for injured patients seeking medical care. We aim to compare in-hospital mortality between Saudi Arabia and the United States, adjusting for severity and demographic variables.

Methods

The analysis included 485,611 patients from the U.S. National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) and 5,290 patients from a trauma registry at King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. For comparability, we restricted our sample to NTDB data from level-I public trauma centers (≥400 beds) in the U.S. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of setting (KAMC vs. NTDB) on in-hospital mortality after adjusting for age, sex, Triage-Revised Scale (T-RTS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), mechanism of injury, hypotension, surgery and head injuries. Interactions between setting and ISS, and predictors were also evaluated.

Results

Injured patients in the Saudi registry were more likely to be males, and younger than those from the NTDB. Patients at the Saudi hospital were at higher risk of in-hospital death than their U.S. counterparts. In the highest severity group (ISSs, 25–75), the odds ratio of in-hospital death in KAMC versus NTDB was 5.0 (95% CI 4.3-5.8). There were no differences in mortality between KAMC and NTDB among patients from lower ISS groups (ISSs, 1–8, 9–15, and 16–24).

Conclusions

Patients who are severely injured following traffic crash injuries in Saudi Arabia are significantly more likely to die in the hospital than comparable patients admitted to large U.S. trauma centers. Further research is needed to identify reasons for this disparity and strategies for improving the care of patients severely injured in traffic crashes in Saudi Arabia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Traffic-related fatalities are a leading cause of premature death worldwide. An estimated 1.2 million individuals are killed in road crashes globally each year. About 90% of these deaths occur in developing countries, although fewer than half of the world’s vehicles are registered in these countries (Peden et al. [2004]). Like many developing countries, Saudi Arabia has struggled with an excess of traffic deaths for decades (Al Ghamdi [2002a]; Al Ghamdi [2002b]; Al-Naami et al. [2010]; Alghnam et al. [2014]; Ansari et al. [2000]; Barrimah et al. [2012]; Nofal and Saeed [1997]). Despite the fact that official statistics tend to underestimate the burden of traffic fatality in Saudi Arabia, (Barrimah et al. [2012]) they report a traffic fatality rate more than double that of the U.S. (Chan [2013]). Several factors likely contribute to the excess traffic fatality in Saudi Arabia, including a high incidence of traffic crash injuries, higher severity, and deficits in healthcare quality, particularly trauma care. Limited data on the burden of injuries in Saudi Arabia is an additional factor that may contribute to the persistence of Saudi Arabia ’s excess traffic fatality. (Al-Naami et al. [2010]; Mock et al. [2004]; Wisborg et al. [2011]) Lack of information can lead to lack of recognition of traffic fatality as a public health concern, and place traffic crashes as a low priority in governmental agendas.

The United States has been successful in reducing traffic fatalities by both improving trauma care and enacting injury prevention strategies (Guan [2006]; MacKenzie et al. [2006]; Nathens et al. [2000a]; Nathens et al. [2000b]). Comparing in-hospital mortality after injury between these two countries may help quantify the extent to which the excess traffic mortality in Saudi Arabia is due to differences in hospital care, and point to opportunities for quality improvement (Boulanger et al. [1993]; Gómez de Segura Nieva et al. [2009]; Hildebrand et al. [2005]; Jenkinson [1999]; Roudsari et al. [2007]; Tan et al. [2012]). Previous studies of cardiac and high-risk surgery outcomes have suggested that providing healthcare settings with information on their risk-adjusted outcomes is associated with subsequent reductions in mortality and morbidity (Hannan [1994]; Khuri [2002]; O’Connor and The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group [1996]).

Because little is known about differences in in-hospital mortality due to trauma between Saudi Arabia and other countries, this study aims to compare in-hospital mortality between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. adjusting for injury severity and demographic variables. Our retrospective analysis of datasets assembled from a large Saudi and multiple U.S. trauma centers employs a direct approach to compare in-hospital mortality across settings.

Methods

Saudi hospital characteristics

King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) is a hospital located in Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia. Thirty percent of traffic crashes in Saudi Arabia occur in or near Riyadh. (Riyadh [2009]) KAMC is one of the largest hospitals in Riyadh with over 700 beds. KAMC also has a 132-bed Emergency Department (ED). This hospital serves primarily eastern metropolitan Riyadh and its surrounding areas within the province of Riyadh.

KAMC provides free healthcare, including all medical procedures and medications, for National Guard employees and their families. Patients not affiliated with the National Guard System receive free healthcare if they seek medical attention through the ED. As a result, the ED receives a large number of patient visits each year, exceeding 200,000 in 2010 ([2011]). About 35% of all ED visits lead to hospital admission. KAMC is equipped to treat complex trauma cases 24 hours a day, providing care from specialized teams including emergency physicians, and general, and orthopedic surgeons. Based on published guidelines (Nathens et al. [2004]; Tintinalli et al. [2010]), resources at KAMC resemble those at level I trauma centers in the United States. KAMC has accreditation under the Joint Commission International standards with excellent performance since December 2006. In addition, KAMC has been designated by the American College of Surgeons as a provider of training in Advanced Trauma Life Support in Saudi Arabia since 1990 (Alkhatib [2009]).

Datasets

This is a retrospective analysis using two existing datasets: the KAMC Saudi Trauma Registry and the U.S. National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB).

Saudi trauma registry

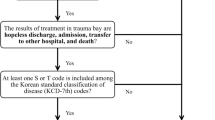

The Saudi Trauma Registry is a prospectively recorded database initiated in 2001. An injured patient must meet at least one of the following criteria to be included: (1) admission to the hospital ward or intensive care unit from the ED; (2) transfer to urgent surgery from the ED; (3) indirect admission (patient discharged from ED and asked to return later); or (4) death after arrival to the ED.

A structured data checklist is used to gather information on patient demographic, physiologic (i.e. Triage-Revised Trauma Scale (Baker and Li [2012]), anatomic (i.e. Injury Severity Score (Schluter [2011a]), and outcome variables. A nurse fills in the checklist and a trained research coordinator ensures that it is complete, tracks missing data, and enters the information into the registry using Microsoft® Access software. Data on post-discharge visits and information about co-morbidities are not included. Some of the variables available in this dataset are the following: Demographics (age, sex), mechanism of injury (motor vehicle crash, fall, motorcycle, violence), severity measures, hospital length of stay, and disposition.

U.S. National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB)

The NTDB, managed by the American College of Surgeons, is the largest trauma dataset ever assembled in the U.S (Haider et al. [2012b]; Haider et al. [2012a]; Haider et al. [2009]). Information in this registry is voluntarily reported by more than 700 trauma centers and hospitals in the United States and its territories. It includes detailed information on type, location, and severity of injuries as well as patient demographics. The NTDB also contains information on procedures performed as well as patient discharge disposition. Observations mostly come from level I or II trauma centers, where more resources are available to meet urgent needs, such as specialized surgery. Therefore, trauma care is expected to be more advanced and well equipped than in other healthcare settings (i.e. a level IV trauma center) (Guan [2006]; Nathens et al. [2004]).

The inclusion criteria (Neal [2013]) for the NTDB are: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnosis 800.00–959.9 and either (1) admission; (2) transfer via EMS transport (including air ambulance) from one hospital to another hospital, or (3) death after receiving any evaluation or treatment; or being dead on arrival (Neal [2013]). Patients with the following ICD-9-CM discharge diagnoses are excluded from this dataset: 905–909 (late effects of injury), 910–924 (blisters, contusions, abrasion, and insect bites), and 930–939 (foreign bodies).

Patient population and selection

This study focuses specifically on patients injured in traffic related crashes. A crash is defined as any traffic-related collision involving a motorized or non-motorized vehicle including: single vehicle (car/bicycle/motorcycle), two vehicles or more, or a pedestrian struck by a vehicle. The KAMC’s registry did not have a separate category for bicyclists and included them with pedestrians because bicycling is rare in Saudi Arabia. However, since the NTDB uses ICD-9 to classify causes of injuries, bicycling can be retained as separate injury mechanism. We chose to keep bicycling as a separate mechanism because grouping them with pedestrians as was done in Saudi Arabia would have reduced comparability of the pedestrian category. Other approaches (e.g. exclusion, inclusion with pedestrians) did not change findings.

Patients in KAMC are included in this analysis if they were seen in the ED between the years 2001 and 2010. The U.S. sample was obtained from the NTDB for the years 2002–2010. In the U.S. dataset, an ICD-9 E code is used to classify injury. We included patients who had ICD-9 external causes of injury in the range of E810-E819, which indicates a traffic-related cause. This approach was based on the recommended framework for injury and mortality data of the Center of Disease and Control (Haider et al. [2009]). No information about patient re-admission was available in either of the datasets.

Because the Saudi registry comes from a large public hospital, we limited the comparison group (U.S.) to 162 public, level I hospitals (≥400 beds). Trauma-center levels in the U.S. were based on designation by states or verification by the American College of Surgeons (MacKenzie et al. [2006]).

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome is death in the emergency department or during the hospital stay. ED deaths are those who arrived alive and had baseline assessment data (i.e. SBP) then died while death on arrival (DOA) were patients who had no baseline vitals and as a result were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

STATA version 12 for Mac (STATA Corp., College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses. To examine differences in health outcome across the two settings, the datasets were combined into a single analysis file. Patients were compared on the following variables: age, sex, mechanism of injury, Triage-Revised Trauma Scale (T-RTS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), presence of head injuries, surgery, and hypotension at admission (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg.). Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables and Chi-square tests to compare categorical variables and proportions between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. Because there are documented differences within the U.S. in trauma outcomes (Shafi et al. [2010]; Shafi et al. [2009]), we divided in-hospital mortality into deciles and plotted how KAMC ranks relative to other hospitals in the overall distribution.

Unadjusted and adjusted mortality were compared between settings using logistic regression with an indicator variable for setting. The following variables were included in the multivariable analysis: age, sex, ISS, T-RTS, mechanism of injury (motor vehicle occupant versus pedestrian, or motorcyclist), an indicator for transfer to surgery from the ED, an indicator for head injury, and an indicator for being hypotensive (Glance et al. [2012]; Haider et al. [2012b]; Kimura et al. [2012]; Schluter [2011a]). Based on prior literature ISS was entered into the model as a categorical variable (1–8, 9–15, 16–24 and 25–75) (Haider et al. [2012b]; Schluter [2011b]). To identify potential subgroups with higher or lower difference between settings, we tested for interaction effects. The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with ninety-five percent confidence intervals. A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding individuals who died in the ED prior to hospital admission. For variables with interaction effects, adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are shown for relevant subgroups.

Missing observations

The Saudi dataset contains very few missing observations (<1%). In the U.S. NTDB, 85% of all patients had complete information and the majority of those with missing information (~12%) were missing either one or two variables. The use of multiple imputation (Galvagno et al. [2012]; Glance et al. [2009]; Haider et al. [2012a]; Moore et al. [2012]; Oyetunji et al. [2011]) did not change our findings, therefore, we chose to present the complete case analysis.

Ethical review

This study was reviewed and approved by both the Institutional Review Board at King Abdulaziz Medical City and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Results

Patient characteristics

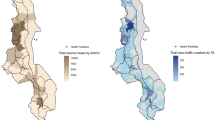

A total of 5,290 patients from KAMC and 485,611 from the NTDB were included in the analysis. There were several differences in patient characteristics between settings (Table 1). The overall population of KAMC was significantly younger than that of the NTDB (60.1% 25 years or younger vs. 34.2%, p < 0.001). In addition, the proportion of males in KAMC was higher than in the U.S. (85.5% vs. 63.4%, p < 0.001). The overall mean of the ISS indicated worse status of patients admitted to KAMC than patients from the NTDB although the difference was small. There were 21 KAMC patients with an ISS = 75 (unsurvivable score), who all died in the hospital. On the other hand, only 44% of those with a similar score died among NTDB patients, and our findings were not very different when patients with ISS = 75 were excluded. In addition, the proportion of hypotensives was significantly higher in KAMC than the NTDB. Four hundred forty-three (8.5%) patients in KAMC and 20,928 (4.3%) in the NTDB died at the hospital (Table 1). Mortalities by hospital in the NTDB ranged from 0% to 12.2% with only 3 hospitals having mortality higher than KAMC (Figure 1). The difference in mortality between KAMC and the NTDB was present across study years, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Regression results

Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses estimated in-hospital mortality to be higher in KAMC than in the NTDB (Tables 2 and 3). Interaction effects indicated that as ISS increased, so did the odds ratio of in-hospital death in KAMC versus the U.S (p < 0.001). Odds ratios were also significantly higher in older age groups (p < 0.001) and for those with versus without head injuries (p < 0.001). (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study shows that even after taking into account demographic and severity differences, injured patients hospitalized following traffic injuries in Saudi Arabia are more likely to die in the hospital than comparable patients admitted to large U.S. trauma centers. This difference was not seen in patients sustaining mild to moderate injuries, with ISSs 1–24.

We are not aware of any previous study that compared trauma mortality between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. The findings from our study are consistent with those of Mock et al., which demonstrated disparity in trauma mortality between developing and developed countries (Mock et al. [1998]). Furthermore, Perel et al. ([2012]) examined differences in trauma mortality in a large multicenter study and found patients treated in low and middle-income countries to be at higher risk of in-hospital death even after taking into account severity and demographic differences. Both of these previous studies used economic indicators as a measure of development. Although Saudi Arabia is a high-income country, it is still considered a developing country (Klugman [2011]) and resembles many low-middle income countries in terms of development indicators and infrastructure for trauma systems.

There are several potential explanations for outcome disparities found in our data for which further research is needed. It is likely that U.S. hospitals are in a better position to adopt new life-saving technologies that improve diagnosis and expedite urgent care for severely injured patients. In addition, trauma care training in the U.S. may be more advanced than programs in Saudi Arabia, which may affect the skill sets of the triage team and potentially lead to better outcomes. Although KAMC meets the criteria of a level I trauma center in the U.S., it has not gone through the formal processes of verification by either the American College of Surgeons or another entity in the United States. Therefore, it is possible that unmeasured differences in trauma resources exist in the two populations, and led to the disparity in outcome.

Higher rates of nosocomial infections (Rosenthal et al. [2012]) or limited access to blood reserves in developing countries may impact trauma mortality regardless of trauma care quality. However, it is unlikely that this is the case in Saudi Arabia because reported rates of nosocomial infection are similar to those in developed countries (Sabra and Abdel fattah [2012]) and because KAMC has a policy in place to maintain sufficient blood supply to keep up with the large patient population they serve.

Another potential explanation concerns differences in driving environments and demographics between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. There were more male patients in the Saudi registry than in the NTDB (85% vs. 63%, p < 0.001). This gender difference is a reflection of the fact that Saudi Arabia does not allow women to drive motor vehicles. In addition to skewing the sex ratio, this can potentially increase the number of occupants at the time of a traffic crash. Additionally, the average size of Saudi Arabian families is larger than U.S. families (Briana [2010]; [2012b]). Consequently, each traffic crash that occurs in Saudi Arabia is likely to injure more individuals than in the U.S. This in turn may lead to more patients requiring urgent interventions at the same time, which adds to the burden the ED has to deal with when patients are treated.

Our findings indicate the presence of effect modification by trauma severity and age. Odds ratios for mortality in KAMC were greater with higher ISS and brain injury. The absence of a mortality gradient among those with mild to moderate injuries indicates that with lower severity injuries, quality of care may not be a major factor affecting risk of mortality. Another way to see this is that, for mild and moderate injuries, KAMC performed well in terms of mortality compared to large U.S. trauma centers but disparity emerged as severity scores became higher. The possibility remains that the effect modification was due to severely injured patients at KAMC being more severe than captured by the scales. However, it seems unlikely that omitted severity components would exist that are strong enough to explain the steep gradient. This mortality difference also was unaffected by categorizing ISS score since using it as a continuous variable yielded similar results.

Unexpectedly, mean ISS values were not substantially higher for trauma patients admitted to KAMC than for those admitted to large U.S. trauma centers (12.9 vs. 12.1). The comparison may be biased if the high number of patients at KAMC led to under-triage (underestimating severity of trauma patients) (Richard Beebe [2011]). One may also speculate that the ISS difference would have been larger if the quality of medical care at the scene and during transport was comparable. If severely injured patients in Saudi Arabia were more likely to die at the scene or on the way to the hospital than in the U.S. due to a relative paucity of rapid emergency transport and skilled paramedics, average ISS among those admitted to the ER would have been lowered. On the other hand, worse pre-admission care could have increased severity in some patients. Paramedics in Saudi Arabia have Basic Life Support (BLS) training but may not be able to perform advanced life saving procedures. In addition, we found that bystanders, who mostly have no medical training, transported 37% of KAMC patients (not shown). Without further detailed study, it is difficult to assess the role of pre-admission care in the severity of admitted patients.

Because our study utilized about 10 years of hospital admissions, it is possible that clinical care has changed over the study period potentially affecting our findings. However, this would be more of a concern if the change in trauma care led to differential change in mortality in either population. When we examined in-hospital mortality in the two populations over the study period, we did not find any major trends in mortality (Figure 2).

It was not clear whether patients who arrived to the ED with CPR in progress and then pronounced dead were included as death upon arrival or as in-hospital deaths in both KAMC and NTDB. This may potentially affect our findings because counting deaths following “CPR in progress” as being in hospital would increase the estimated mortality. If this was done more frequently at KAMC, for example, we would have overestimated mortality disparity. However, it is unlikely that such considerations would have drastically affected our findings because when we excluded patients who died in the ED prior to hospital admission, the results were not very different (Table 2).

Unmeasured confounders that we were not able to address in our analysis may also have affected our findings. For example, unknown differences in the frequency and severity of preexisting conditions among the two patient populations could have contributed to the mortality differences observed. Another unmeasured confounder is population or system wide differences that could have affected patients’ trajectory after injury. Our study examined patients’ outcome after arrival to the ED. However, it is possible that population level differences between the two countries may have had a role in the patient condition prior to admission and led to differential deterioration rate between the two groups. One example of system wide difference is the distance to trauma centers, which have been found to be associated with patient outcomes (Crandall et al. [2013]; Durkin et al. [2005]).

The NTDB has potential to improve trauma care and outcomes in the U.S. (Haider et al. [2012b]; Haider et al. [2012a]) and worldwide. Although missing data, incorrect recording and data entry errors are likely to occur (Neal [2009]), its large size, detailed information and standardized structure allow answering many questions pertaining to trauma outcomes. Inviting other countries to establish similar registries has the potential to enable international collaborations and help improve trauma outcomes globally. In addition, future research utilizing NTDB for international research will contribute to existing knowledge. For example, two recent studies by Haider et al. (Haider et al. [2014]; Haider et al. [2013]) used the NTDB to shed some light on trauma outcome in other countries relative to the U.S.

Despite limitations, the results of our analysis are generalizable to patients treated in KAMC and provide some insights into the difference in trauma outcomes between Saudi Arabia and the U.S.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that patients injured in traffic crashes in Saudi Arabia are more likely to die after admission to the emergency department in one of the best equipped Saudi hospitals than patients admitted to large U.S. trauma centers. This excess in-hospital mortality in Saudi Arabia was present only for patients sustaining relatively severe injuries, and it was higher with increasing severity and higher age. While it is not possible to pinpoint a specific cause of the disparity, this study showed that there is room for further improvement of KAMC’s outcome. Future studies should explore reasons for outcome discrepancies among severely injured patients in order to improve the quality of care and reduce the burden of preventable mortality.

Quality improvement programs in Saudi Arabia can use these findings as a reference when examining mortality outcomes in the future to identify changes in trauma outcomes. In addition, the direct comparison approach we used in this study provides a model for future studies from other developing countries to compare outcomes with a large resource such as the NTDB.

Abbreviations

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- KAMC:

-

King Abdulaziz Medical City

- NTDB:

-

National Trauma Data Bank

- RTS:

-

Revised Trauma Scale

- T-RTS:

-

Triage Revised Trauma Scale

- TRISS:

-

Trauma Injury Severity Scoring

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pressure

Reference

Achievement_Report_2010 [Internet]. Riyadh; 2011. Available from: ., [https://secure.ngha.med.sa/ngha/iaod/nghapub/,DanaInfo=portal.ngha.med+NGHA_Achievement_Report_2010.pdf]

Al Ghamdi AS: Emergency medical service rescue times in Riyadh. Accid Anal Prev [Internet] 2002a,34(4):499–505. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12067112 10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00047-1

Al Ghamdi AS: Pedestrian-vehicle crashes and analytical techniques for stratified contingency tables. Accid Anal Prev [Internet] 2002b,34(2):205–214. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11829290 10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00015-X

Al Naami MY, Arafah MA, Al Ibrahim FS: Trauma care systems in Saudi Arabia: an agenda for action. Ann Saudi Med [Internet] [cited 2010,30(1):50–58. Available from: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2850182&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract] http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2850182&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Alghnam S, Palta M, Hamedani A, Alkelya M, Remington PL, Durkin MS. Predicting in-Hospital Death Among Patients Injured in Traffic Crashes in Saudi Arabia. Injury [Internet]: Elsevier Ltd; 2014. Jun [cited 2014 Jun 17]; Available from: ., [http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S002013831400268X]

Alkhatib J. Advanced Trauma Life Support international [Internet]; 2009. Cited 2013 Feb 6]. p. 2. Available from: ., [http://www.facs.org/trauma/atls/pdf/international-dec09.pdf]

Ansari S, Akhdar F, Mandoorah M, Moutaery K: Causes and effects of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. Public Health [Internet] 2000,114(1):37–39. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10787024 10.1038/sj.ph.1900610

Baker SP, Li G: Injury Research: Theories, Methods, and Approaches. Springer, New York (NY); 2012.

Barrimah I, Midhet F, Sharaf F: Epidemiology of road traffic injuries in qassim region, Saudi Arabia: consistency of police abstract: road traffic injuries (RTI) are a major public health problem worldwide and a major cause of death and disability. Furthermore According W 2012, 6: 1.

Boulanger BR, McLellan BA, Sharkey PW, Rizoli S, Mitchell K, Rodriguez A, Bernard Boulanger BM: A comparison between a Canadian regional trauma unit and an American level I trauma center. J Trauma [Internet] 1993,35(2):261. Available from: [http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Abstract/1993/08000/A_Comparison_Between_A_Canadian_Regional_Trauma.15.aspx] http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Abstract/1993/08000/A_Comparison_Between_A_Canadian_Regional_Trauma.15.aspx 10.1097/00005373-199308000-00015

Briana K. U.S. Census Bureau Report [Internet]; 2010. Available from: ., [http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/families_households/cb10–174.html]

Chan M. The Global status report on road safety 2013 [Internet]. Geneva: 2013: p. 2–10. Available from: ., [http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2013/report/en/index.html]

Crandall M, Sharp D, Unger E, Straus D, Brasel K, Hsia R, Esposito T: Trauma deserts: distance from a trauma center, transport times, and mortality from gunshot wounds in Chicago. Am J Public Health [Internet] 2013,103(6):1103–1109. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23597339 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301223

Durkin M, McElroy J, Guan H, Bigelow W, Brazelton T: Geographic analysis of traffic injury in Wisconsin: impact on case fatality of distance to level I/II trauma care. WMJ [Internet] 2005,104(2):26–31. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15856738

Galvagno SM, Haut ER, Zafar SN, Millin MG, Efron DT, Koenig GJ, Baker SP, Bowman SM, Pronovost PJ, Haider AH: Association between helicopter vs ground emergency medical services and survival for adults with major trauma. JAMA [Internet] 2012,307(15):1602–1610. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22511688 10.1001/jama.2012.467

Glance LG, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Dick AW: Outcomes of adult trauma patients admitted to trauma centers in pennsylvania, 2000–2009. Arch Surg [Internet] 2012,147(8):732–737. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22911068 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1138

Glance LG, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Meredith W, Dick AW: Impact of statistical approaches for handling missing data on trauma center quality. Ann Surg [Internet] 2009,249(1):143–148. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19106690 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e544b

Gómez De Segura Nieva JL, Boncompte MM, Sucunza AE, Louis CLJ, Seguí Gómez M, Otano TB: Comparison of mortality due to severe multiple trauma in two comprehensive models of emergency care: Atlantic Pyrenees (France) and Navarra (Spain). J Emerg Med [Internet] Elsevier Inc 2009,37(2):189–200. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18829202

Guan H. Access to level I or II Trauma Center & Traffic Related Trauma Outcomes. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2006: p. 3.

Haider AH, Chang DC, Haut ER, Cornwell EE, Efron DT: Mechanism of injury predicts patient mortality and impairment after blunt trauma. J Surg Res [Internet] Elsevier Inc 2009,153(1):138–142. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18805554 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.011

Haider AH, David JS, Zafar SN, Gueugniaud PY, Efron DT, Floccard B, MacKenzie EJ, Voiglio E: Comparative effectiveness of inhospital trauma resuscitation at a French trauma center and matched patients treated in the United States. Ann Surg [Internet] 2013,258(1):178–183. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23478519 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828226b6

Haider AH, Hashmi ZG, Gupta S, Zafar SN, David JS, Efron DT, Stevens KA, Zafar H, Schneider EB, Voiglio E, Coimbra R, Haut ER: Benchmarking of Trauma Care Worldwide: The Potential Value of an International Trauma Data Bank (ITDB). World J Surg [Internet] 2014, 38: 1882–1891. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24817407 10.1007/s00268-014-2629-5

Haider AH, Saleem T, Leow JJ, Villegas CV, Kisat M, Schneider EB, Stevens KA, Cornwell EE, MacKenzie EJ, Efron DT: Influence of the National Trauma Data Bank on the study of trauma outcomes: is it time to set research best practices to further enhance its impact? J Am Coll Surg [Internet] Elsevier Inc 2012a,214(5):756–768. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22321521 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.013

Haider AH, Villegas CV, Saleem T, Efron DT, Stevens KA, Oyetunji TA, Cornwell EE, Bowman S, Haack S, Baker SP, Schneider EB: Should the IDC-9 Trauma Mortality Prediction Model become the new paradigm for benchmarking trauma outcomes? J Trauma Acute Care Surg [Internet] 2012b,72(6):1695–1701. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22695443 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256a010

Hannan EL: Improving the outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery in New York State. JAMA J Am Med Assoc [Internet] AMER MED ASSOC 1994,271(10):761–766. 10.1001/jama.1994.03510340051033

Hildebrand F, Giannoudis PV, Van GM, Zelle B, Ulmer B, Krettek C, Bellamy MC, Pape HC: Management of polytraumatized patients with associated blunt chest trauma: a comparison of two European countries. Injury [Internet] 2005,36(2):293–302. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15664594 10.1016/j.injury.2004.08.012

Jenkinson C: Comparison of UK and US methods for weighting and scoring the SF-36 summary measures. J Public Health Med [Internet] 1999,21(4):372–376. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11469357 10.1093/pubmed/21.4.372

Khuri SF: The Comparative Assessment and Improvement of Quality of Surgical Care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Arch Surg [Internet] AMER MED ASSOC 2002,137(1):20–27. Available from: [http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/CitedFullRecord.do?product=WOS&colName=WOS&SID=4C@6odIaK8cPOnlLioD&search_mode=CitedFullRecord&isickref=WOS:000173300200003&cacheurlFromRightClick=no] http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/CitedFullRecord.do?product=WOS&colName=WOS&SID=4C@6odIaK8cPOnlLioD&search_mode=CitedFullRecord&isickref=WOS:000173300200003&cacheurlFromRightClick=no 10.1001/archsurg.137.1.20

Kimura A, Nakahara S, Chadbunchachai W: The development of simple survival prediction models for blunt trauma victims treated at Asian emergency centers. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med [Internet] 2012, 20: 9. Available from: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3471327&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract] http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3471327&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.1186/1757-7241-20-9

Klugman J. Human Development Report. New York; 2011: p. 39.

MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, Salkever DS, Scharfstein DO: A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2006,354(4):366–378. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16436768 10.1056/NEJMsa052049

Mock C, Quansah R, Krishnan R, Arreola-Risa C, Rivara F: Strengthening the prevention and care of injuries worldwide. Lancet [Internet] 2004,363(9427):2172–2179. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15220042 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16510-0

Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ, Nii Amon Kotei D, Arreola Risa C, Maier RV, Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ, Nii Amon Kotei D, Arreola Risa C, Maier RV: Trauma mortality patterns in three nations at different economic levels: implications for global trauma system development. J Trauma [Internet] 1998,44(5):804–812. discussion 812–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9603081 10.1097/00005373-199805000-00011

Moore L, Hanley JA, Turgeon AF, Lavoie A: Comparing regression-adjusted mortality to standardized mortality ratios for trauma center profiling. J Emerg Trauma Shock [Internet] 2012,5(4):333–337. Available from: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3519047&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract] http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3519047&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.4103/0974-2700.102404

Nathens AB, Brunet FP, Maier RV: Development of trauma systems and effect on outcomes after injury. Lancet [Internet] 2004,363(9423):1794–1801. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15172780 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16307-1

Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Cummings P, Rivara FP, Maier RV: The effect of organized systems of trauma care on motor vehicle crash mortality. JAMA [Internet] 2000a,283(15):1990–1994. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10789667 10.1001/jama.283.15.1990

Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Maier RV: Effectiveness of state trauma systems in reducing injury-related mortality: a national evaluation. J Trauma [Internet] 2000b,48(1):25–30. discussion 30–1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10647561 10.1097/00005373-200001000-00005

Neal M. NTDB Research Data Set v. 7.2 [Internet]. Chicago; 2009: p. 2. Available from: ., [http://www.facs.org/trauma/ntdb/]

Neal M. American College of Surgeons [Internet]; 2013. Available from: ., [http://www.facs.org/trauma/ntdb/ntdbapp.html]

Nofal F, Saeed A: Seasonal variation and weather effects on road traffic accidents in Riyadh city. Public Health [Internet] 1997, 111: 51–55. Available from: [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350697000115] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350697000115 10.1038/sj.ph.1900297

O’Connor GT: A regional intervention to improve the hospital mortality associated with coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA J Am Med Assoc [Internet] AMER MED ASSOC 1996,275(11):841–846. Available from: [http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/CitedFullRecord.do?product=WOS&colName=WOS&SID=4C@6odIaK8cPOnlLioD&search_mode=CitedFullRecord&isickref=WOS:A1996TZ97100026] http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/CitedFullRecord.do?product=WOS&colName=WOS&SID=4C@6odIaK8cPOnlLioD&search_mode=CitedFullRecord&isickref=WOS:A1996TZ97100026 10.1001/jama.1996.03530350023029

Oyetunji TA, Crompton JG, Ehanire ID, Stevens KA, Efron DT, Haut ER, Chang DC, Cornwell EE, Crandall ML, Haider AH: Multiple imputation in trauma disparity research. J Surg Res [Internet] 2011,165(1):e37-e41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21067775 10.1016/j.jss.2010.09.025

Peden M, Scurfield R, Hyder A, Jarawan E, Sleet D, Mohan D, Mathers C. The World report on road traffic injury prevention [Internet]. Geneva; 2004. Available from: ., [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241562609.pdf]

Perel P, Prieto-Merino D, Shakur H, Clayton T, Lecky F, Bouamra O, Russell R, Faulkner M, Steyerberg EW, Roberts I: Predicting early death in patients with traumatic bleeding: development and validation of prognostic model. Bmj [Internet] 2012,345(aug15 1):e5166-e5166. Available from: [10.1136/bmj.e5166] http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.e5166 10.1136/bmj.e5166

Richard Beebe M. Professional Paramedic, Volume III: Trauma Care & EMS Operations; 2011: p. 651.

Riyadh. Traffic Injuries Annual report of Saudi Arabia [Internet]. Riyadh; 2009: p. 43. Available from: ., [http://www.moi.gov.sa/wps/wcm/connect/f8e506ce-5224–4ea8–8488–68b7afdc7393/REport?_1430??.pdf?MOD=AJPERES]

Rosenthal VD, Jarvis WR, Jamulitrat S, Silva CPR, Ramachandran B, Duenas L, Gurskis V, Ersoz G, Novales MGM, Khader IA, Ammar K, Guzmán NB, Navoa Ng JA, Seliem ZS, Espinoza TA, Meng CY, Jayatilleke K: Socioeconomic impact on device-associated infections in pediatric intensive care units of 16 limited-resource countries: international nosocomial infection control consortium findings. Pediatr Crit Care Med [Internet] 2012,13(4):399–406. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22596065 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318238b260

Roudsari BS, Nathens AB, Cameron P, Civil I, Gruen RL, Koepsell TD, Lecky FE, Lefering RL, Liberman M, Mock CN, Oestern HJ, Schildhauer TA, Waydhas C, Rivara FP: International comparison of prehospital trauma care systems. Injury [Internet] 2007,38(9):993–1000. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17640641 10.1016/j.injury.2007.03.028

Sabra SM, Abdel fattah MM: Epidemiological and microbiological profile of nosocomial infection in taif hospitals , KSA ( 2010–2011 ). World J Med Sci 2012,7(1):1–9.

Schluter PJ: The trauma and injury severity score (TRISS) revised. Injury [Internet] 2011a,42(1):90–96. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20851394 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.040

Schluter PJ: Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS): is it time for variable re-categorisations and re-characterisations? Injury [Internet] Elsevier Ltd 2011b,42(1):83–89. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20851396

Shafi S, Parks J, Ahn C, Gentilello LM, Nathens AB: More operations, more deaths? Relationship between operative intervention rates and risk-adjusted mortality at trauma centers. J Trauma [Internet] 2010,69(1):70–77. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20622580 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e28168

Shafi S, Stewart RM, Nathens AB, Friese RS, Frankel H, Gentilello LM: Significant variations in mortality occur at similarly designated trauma centers. Arch Surg [Internet] 2009,144(1):64–68. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19153327 10.1001/archsurg.2008.509

Tan XX, Clement ND, Frink M, Hildebrand F, Krettek C, Probst C: Pre-hospital trauma care: a comparison of two healthcare systems. Indian J Crit Care Med [Internet] 2012,16(1):22–27. Available from: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3338234&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract] http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3338234&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.4103/0972-5229.94421

Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma J, Cline D, Cydulka R. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide; 2010: p. 250.

ᅟWant of Affordable Housing Still Besets Saudi Home Ownership. Riyadh: Saudi Gaz. [Internet]; 2012b. Available from: ?., [http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm]

Wisborg T, Montshiwa TR, Mock C: Trauma research in low- and middle-income countries is urgently needed to strengthen the chain of survival. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med [Internet] BioMed Central Ltd 2011,19(1):62. Available from: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi] http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi? 10.1186/1757-7241-19-62

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Saleem Alonezi for his help preparing the dataset for the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

Study conception and design: SA, MP, AH, PR, MA, MD. Acquisition of data: SA, KA, MA. Analysis and interpretation of data: SA, MP, AH, PR, KA, MA, MD. Drafting of manuscript: SA, MP, AH, PR, MD. Critical revision: SA, MP, AH, PR, KA, MA, MD. All authors read and approved the final msanuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alghnam, S., Palta, M., Hamedani, A. et al. In-hospital mortality among patients injured in motor vehicle crashes in a Saudi Arabian hospital relative to large U.S. trauma centers. Inj. Epidemiol. 1, 21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-014-0021-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-014-0021-4