Abstract

Background

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have among the highest prevalence of adult obesity and type 2 diabetes in the world. This study aimed to estimate the recent prevalence of obesity among school-age children and adolescents in the GCC States.

Methods

The literature search for obesity prevalence data was carried out in July 2017 in Google Scholar, Physical education index, Medline, SCOPUS, WHO, 2007–2017, and updated in November 2018.In addition, 22 experts from the GCC were contacted to check the search results, and to suggest studies or grey literature which had been missed. Eligible studies were assessed for quality by using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for prevalence studies. Conduct of the systematic review followed the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews Tool (AMSTAR) guidance. A narrative synthesis was conducted.

Results

Out of 392 studies identified, 41 full-text reports were screened for eligibility; 11 of which were eligible and so were included, from 3 of the 6 GCC countries (United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia). Surveillance seems good in Kuwait in compared to other countries, with one recent national survey of prevalence. Quality of the eligible studies was generally low-moderate according to the JNBI tool: representative samples were rare; participation rates low; power calculations were mentioned by only 3/11 studies and confidence intervals around prevalence estimates provided by only 3/11 eligible studies; none of the studies acknowledged that prevalence estimates were conservative (being based on BMI-for-age). There was generally a very high prevalence of obesity (at least one quarter-one third of study or survey participants obese according to BMI-for-age), prevalence increased with age, and was consistently higher in boys than girls.

Conclusions

The prevalence of obesity among school-age children and adolescents appears to have reached alarming levels in the GCC, but there are a number of major gaps and limitations in obesity surveillance in the GCC states. More national surveys of child and adolescent obesity prevalence are required for the GCC states.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration number CRD42017073692.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Gulf Cooperation council countries include Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Bahrain, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), and Oman. The GCC countries have among the highest adult obesity and type 2 diabetes prevalence in the world [1,2,3,4] with rapidly increasing prevalence of adult obesity and diabetes in the past two decades [1]. Several factors have contributed to the high prevalence of obesity in the GCC countries [2], notably the very large and rapid increases in household income, with associated lifestyle changes that include reduced physical activity and increased consumption of obesogenic foods and drinks [5, 6].

Surveillance of childhood obesity is considered central to tackling the obesity epidemic [7], but there may be a number of important limitations in surveillance of child and adolescent obesity prevalence in the GCC at present. Specifically, we were unable to find a recent systematic review of obesity prevalence of children and adolescents in the GCC, so prevalence of the problem is unclear. Our initial scoping review also suggested that many previous studies combined the prevalence of overweight and obesity, and so the prevalence of obesity could not be determined. In addition, many previous studies in the GCC collected data over 10 years ago and these studies may now be out of date given the rapid increases in prevalence in the region [8, 9]. The recently published global estimates of obesity prevalence [10, 11] used data from the GCC countries which were also over 10 years old for example, so there is a need for prevalence data from more recent studies and surveys. An additional problem with older evidence is the fact that definitions of child and adolescent obesity have evolved over the past decade. Specifically, the WHO definition of child and adolescent obesity based on BMI-for-age was not published until 2007, and was not in widespread use until some time after that. A further problem with existing obesity prevalence data is that systematic reviews demonstrating limitations of BMI-for-age as a surveillance tool (high specificity for excessive fatness, but only low-moderate sensitivity) have become available only relatively recently [12, 13] and recent obesity prevalence studies or surveys from the GCC countries may not have made allowances for this important source of bias in prevalence estimates.

The primary aim of the present study was therefore to establish the recent (last 11 years) prevalence of obesity among school-age children and adolescents in the GCC states. Secondary aims were: to identify differences in prevalence between countries and between groups (e.g. by gender, age); to identify major gaps and weaknesses in the evidence base on obesity prevalence in the GCC. The study was intended to help improve child and adolescent obesity surveillance in the GCC in future, so that public health action aimed at tackling the obesity epidemic in the GCC can be better informed [7].

Methods

Registration and reporting of the systematic review

This systematic literature review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines [14]. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO on the 10th September 2017 (registration number CRD42017073692), the international prospective register for systematic reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=73692). The search strategy followed the PECO (population, exposure, comparator and outcome) format: population = school-age children and adolescents in the GCC countries; exposure = obesity as defined using BMI-for-age; comparator = any appropriate BMI-for-age reference data; outcome = prevalence of obesity among the general population since 2007.

Literature search

The literature search was originally conducted on 17 July 2017. The manuscript was submitted to this journal on 28th February 2018 and reviews were not received until October 2018, so the original searches were repeated on 2nd November 2018. Searches used the five most relevant electronic databases: Medline, Google Scholar, Physical education Index, SCOPUS and WHO. The search terms used in Medline are provided in Additional file 1: Table S1, as required by the PRISMA checklist; terms were very similar in the other databases, though with small differences in syntax between databases. The electronic database searching was complemented by reference citation tracking (forward and backward) of the included studies and of previous reviews, consultation with GCC-based experts in the field, and a search for ‘grey literature’ among the GCC experts (summarised in Additional file 2: Table S2).

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they satisfied all of the following inclusion criteria: Prevalence data were collected in the last 11 years, i.e. from Jan 2007 to end October 2018; from a GCC country (Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, KSA, UAE); they provided prevalence of obesity rather than overweight prevalence, or prevalence of overweight/obesity combined; they must have defined obesity using an accepted method for children and adolescents based on BMI-for-age; BMI must have been based on measured height and weight (rather than self-report or parental report); age of study participants between 5 and 19 years; study participants from the general population (e.g. not from clinical samples).

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they addressed prevalence of obesity in middle Eastern countries that are not members of the GCC, with study participants outside the range 5–19; if prevalence data were collected earlier than 2007; if prevalence estimates from BMI-for-age were based on self-reported height or weight, or which combined prevalence of obesity and overweight so that obesity prevalence could not be ascertained. Studies that sampled from specific populations (e.g. clinical populations) were also excluded.

All literature search hits, and all potentially eligible studies identified by forward and backward citation searching, were examined for eligibility independently by both authors. The two authors resolved differences of opinion over eligibility by discussion, and in a few cases, by asking for clarification of methods from the authors of the original studies (e.g. over the precise data collection period where this was unclear in a few cases). A list of studies excluded at the full-text screening stage, with reason(s) for exclusion is providing in the supplementary material (Additional file 3: Table S3).

Data extraction

A data extraction form was devised in advance of the process of data extraction and used to populate the evidence tables given in the Results section below, with summary data on prevalence of obesity (with 95% CI where possible) overall, and by subgroup as reported (e.g. by age, gender, definition of obesity). Both authors independently populated the data extraction forms, and they resolved any differences of opinion by discussion.

Quality assessment-appraisal of eligible studies

The quality of individual eligible studies was assessed by both authors independently using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for assessment of the quality of prevalence studies [15]. Two additional aspects of prevalence study quality which are specific to obesity were also considered and added to the data extraction forms: the timing of data collection-given recent rapid increases in obesity prevalence in the GCC; [8, 9]; whether biases arising from use of the BMI-for-age to estimate obesity prevalence [12, 13] had been considered by the authors (e.g. reported in the Discussion and/or used to adjust prevalence estimates in the Results).

Guidance on maintaining the quality of the systematic review

In an attempt to ensure high quality of the present review process the authors planned and conducted the review by addressing each of the items in the Assessment of multiple systematic reviews tool (AMSTAR [16]) checklist -the process is summarised in Table 1.

Synthesis of study findings

A meta-analysis of review findings was considered desirable if practical, but it was recognised that marked gaps in the evidence and /or differences between studies, e.g. differences in age or sex, ethnicity or socio-economic status of the samples, differences in time period [17], differences arising from differences in the definition of obesity used -which would be expected to be marked [12]-might preclude meta-analysis. Publication bias assessment was also considered desirable if possible.

Results

Eligible studies and study selection process

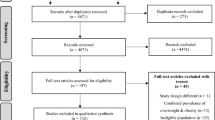

The PRISMA flow diagram is provided in Fig. 1. In the original search twenty-two potentially eligible papers were identified for full-text eligibility screening by both authors by the conventional literature searching and a further 17 papers/surveys from the grey literature were suggested by expert contacts in the GCC and all of those were full-text screened by both authors. The search update in November 2018 identified further studies for full-text screening but no additional eligible studies, so only 11 eligible papers/survey reports were identified, reporting 13 separate prevalence estimates, from 3 of the 6 GCC countries (UAE, Kuwait, KSA): there were no eligible studies from Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar. In summary, the number of eligible studies in the GCC countries was limited and the studies/surveys themselves differed substantially by time, sample age and sex, ethnicity, and by definitions of obesity used. No formal assessment of publication bias was possible given the small number of eligible studies, and so a narrative synthesis, by nation, is provided below.

PRISMA Study Flow Diagram. Footnote: search updates in November 2018 identified 10 additional potentially eligible studies, of which 6 were excluded from Abstract screening and four were deemed ineligible after full-text screening (see Additional file 3)

Study quality appraisal

The formal appraisal of study quality for the 11 eligible studies/surveys is summarised in Table 2. A number of the quality assessment items were not reported or not carried out, in particular the use of nationally representative samples was rare (1/11 eligible studies), and few studies reported power calculations or confidence intervals for their prevalence estimates (only 3/11 provided confidence intervals). In addition, few of the eligible studies/surveys were recent: 9 out of 11 studies collected data over 7 years ago. Finally, consideration of biases arising from use of BMI-for-age was not carried out (0/11 eligible studies referred to this major source of bias).

Narrative synthesis by GCC nation

UAE

Table 3 summarises the three eligible studies from the UAE [18,19,20]. None of the three studies used representative samples, though one study [18] was very large (n = 44,942), relatively recent (data collection 2013–2015), included both nationals and non-nationals, and included a wide age range (3–18 years). In this study [18] by prevalence of obesity according to the WHO definition exceeded one third of the sample in the secondary school-age participants, and there was clear evidence of increasing prevalence with increasing age. The highest prevalence was recorded for age 11–14 years. In two of the three studies from the UAE [19, 20] obesity prevalence estimates were provided using more than one definition of obesity, and in both cases prevalence was substantially lower using the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) compared to the alternative definitions (from the US Centers for Disease Control and WHO respectively). In the one study which considered differences in obesity prevalence between the sexes, prevalence was much lower among girls than boys [19] .

KSA

Table 4 summarises the evidence from the two eligible studies in the KSA [21, 22]. Neither of these studies was based on nationally representative samples. Both studies included adolescents only, and in both studies prevalence of obesity was much higher in boys than girls.

Kuwait

Table 5 summarises the 8 eligible studies from Kuwait. A number of the eligible studies were not based on representative samples, were not very recent, and had relatively small samples. The most informative of the data sources from Kuwait was the large and recent nationally representative survey from 2016 [23]. In this survey there was clear evidence of increasing prevalence of obesity with increasing age, and by adolescence one-quarter to one third of participants were obese according to the WHO definition. Among the other 7 eligible studies from Kuwait (Table 5), 3 reported comparisons between prevalence estimates according to the definition of obesity used. Prevalence estimates were generally lower with the IOTF definition than the CDC and WHO BMI-for-age definitions (Table 5). Four studies compared prevalence between the sexes, and in all cases found that prevalence was lower among girls than boys, though prevalence was still high among the girls (typically ranging between 20 and 45% of girls in the samples studied).

Discussion

This systematic review showed that evidence on the prevalence of obesity among school age children and adolescents in the GCC states is limited. Only one nationally representative survey was identified, and only 3/6 GCC states had any eligible data from the past 11 years, with multiple gaps in the evidence (e.g. for certain age groups) and weaknesses in the evidence (e.g. reliance on non-representative samples, lack of national surveys). More extensive and higher quality surveillance of obesity among school age children and adolescents in the GCC is required in future if the GCC states are to address the obesity epidemic effectively [7]. Regular high quality surveillance is essential to assess the scale of the obesity problem, to identify trends and inequalities, to drive obesity prevention and control measures, and to assess the impact of policy measures aimed at obesity prevention and control [7].

Despite limitations in the evidence base on obesity prevalence in the GCC nations noted above, some trends were apparent from the 11 eligible studies. First, the prevalence of obesity according to BMI-for-age was very high. For example, prevalence of obesity in UAE according to the WHO definition exceeded one third of the sample in the secondary school-age participants, and increased with increasing age. One-quarter to one third of participants were obese according to the WHO definition in the Kuwaiti national survey. Moreover, BMI-for-age substantially underestimates the prevalence of obesity (excessive fatness) in children [12, 13] so ‘true’ prevalence of obesity in these studies in the GCC would have been even higher if this bias arising from use of the BMI had been accounted for. None of the eligible studies or surveys acknowledged that their prevalence estimates were subject to this source of bias, or attempted to adjust for it. A large recent study [24] across Africa found that the WHO-BMI-for-age definition of obesity only identified around one third of children with excessive body fatness measured by a reference method (Total Body Water). Second, in most of the eligible studies the prevalence of obesity was higher in boys than girls, suggesting that this is a real difference in susceptibility to paediatric obesity in the GCC states. It should be noted that prevalence of obesity among the girls would also be regarded as very high relative to other nations [10, 11]. Third, the eligible studies and surveys which compared prevalence estimates by the different definitions based on BMI-for-age found consistently that prevalence was substantially lower when the IOTF definition of obesity was used compared to definitions based on the CDC or WHO, consistent with previous evidence [12].

There are no previous systematic reviews of the prevalence of child or adolescent obesity from the GCC, and so the results of the present study cannot be compared easily with other evidence. Comparisons of prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in the GCC with those living in other countries is also difficult because of differences in the timing of the studies, differences in the definitions of obesity used, and whether or not obesity prevalence estimates (as distinct from overweight prevalence estimates, or prevalence of overweight and obesity combined) can be found in published studies.

The present review found major limitations of obesity surveillance in the GCC, notably the apparent lack of any recent surveillance data from 3 of the 6 GCC countries, the availability of nationally representative sample data from only 1/6 GCC countries, the small sample sizes and scarcity of power calculations (and confidence intervals around prevalence estimates), and the fact that bias in the use of BMI-for-age to generate prevalence estimates was not considered by any of the 11 eligible studies/surveys. In addition, eligible study and survey response rates were often very low (under 50%), and not reported in all of the eligible studies and surveys. It should be noted that many of the studies did not set out to obtain nationally representative samples, and estimating obesity prevalence was not a primary aim of all of the eligible studies. In addition, a checklist for guiding/assessing the quality of prevalence studies [15] only became available after many of the eligible studies were conducted. Future studies and surveys of child and adolescent obesity prevalence in the GCC states and elsewhere may find it useful to refer to the checklist for assessment of prevalence study quality used in the present study [15].

This review had a number of strengths. First, it focused on obesity-rather than overweight and obesity. While obesity and overweight are often combined somewhat casually in paediatric prevalence studies they are not equivalent clinically or biologically in children, as in adults: there is currently a very large body of consistent evidence of adverse health effects of obesity in childhood and adolescence [23, 25], but the adverse health impact of overweight in childhood and adolescence is much less clear at present. Second, the present review attempted to provide evidence of most relevance and highest quality, by including only relatively recent studies, and only those which used acceptable objective measures of obesity (rather than self-or parent reports), and by formal appraisal of study quality. The conduct of the present systematic review was also intended to follow best practice, by using the AMSTAR tool as a guide to the process, and reporting of the review followed PRISMA guidance. Finally, by making use of extensive expert contacts in all of the 6 GCC states, the probability that eligible studies and surveys (including grey literature) were not identified by the conventional literature search was reduced.

The present review also had a number of limitations. The number of eligible studies was relatively small due in part to our decision to exclude studies which collected data prior to 2007. The rationale for this is that we included only recent studies to provide up to date information, especially important given likely recent rapid increases in obesity prevalence in the GCC [1,2,3,4, 8, 9]. Including older studies would have increased the size of the evidence base, but also made it much less generalisable to contemporary GCC populations. The literature search was limited to English language for practical reasons, but any grey literature or other studies suggested by expert contacts in the GCC published in Arabic would also have been considered if identified. The first author is from Kuwait, which may have biased the grey literature searching towards Kuwaiti sources of evidence. However, author connections in relevant institutions in the rest of the GCC are good, and responses from those contacts were generally informative (Additional file 2). It therefore seems unlikely that useful sources of evidence from the other GCC states, such as recent nationally representative surveys, were missed.

Conclusions

There is a major gap in the literature on the childhood and adolescent obesity prevalence in the GCC states, with the exception of Kuwait. New research/surveys are needed for those countries in the GCC apparently not doing surveillance of child and adolescent obesity prevalence. For those countries where studies and surveys have been carried out, greater attention could be paid to the quality appraisal issues identified by the present review.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

Assessment of systematic reviews tool

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- GCC:

-

the Gulf Cooperation Council

- IOTF:

-

International Obesity Task Force

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- KSA:

-

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- UAE:

-

United Arab Emirates

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Abdul-Rasoul MM. Obesity in children and adolescents in gulf countries: facts and solutions. Advances en Diabetología. 2012;28(3):64–9.

Al-Awadhi N, Al-Kandari N, Al-Hasan T, AlMurjan D, Ali S, Al-Taiar A. Age at menarche and its relationship to body mass index among adolescent girls in Kuwait. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):29.

Hammad SS, Berry DC. The child obesity epidemic in Saudi Arabia: a review of the literature. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;28:505–15.

Boodai SA, Reilly JJ. Health related quality of life of obese adolescents in Kuwait. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:105.

Al-Haifi AR, Al-Fayez MA, Al-Athari BI, Al-Ajmi FA, Allafi AR, Al-Hazzaa HM, Musaiger AO. Relative contribution of physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and dietary habits to the prevalence of obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(1):6–13.

Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Ali HI, Harrison G, Popkin BM. The prevalence and trends of overweight, obesity and nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the Arabian Gulf States. Obes Rev. 2011;12(1):1–13.

Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity Implementation Plan. WHO/NMH/PND/ECHO/17.1, WHO 2017]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259349/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-17.1-eng.pdf;jsessionid=69FE14197C363C78E5E9C969AE9A576D?sequence=1.

Alshaikh MK, Filippidis FT, Al-Omar HA, Rawaf S, Majeed A, Salmasi A-M. The ticking time bomb in lifestyle-related diseases among women in the Gulf cooperation council countries; review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):536.

Al-Refaee FA, Al-Qattan SA, Jaber SM, Al-Mutairi AA, Al-Dhafiri SS, Nassar MF. The rising tide of overweight among Kuwaiti children: study from Al-Adan hospital, Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(6):600–2.

Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Acosta-Cazares B, Acuin C, Adams RJ, Aekplakorn W, Afsana K, Aguilar-Salinas CA. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42.

The Global Burden of Disease Collaborators. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27.

Reilly JJ, Kelly J, Wilson DC. Accuracy of simple clinical and epidemiological definitions of childhood obesity: systematic review and evidence appraisal. Obes Rev. 2010;11(9):645–55.

Javed A, Jumean M, Murad MH, Okorodudu D, Kumar S, Somers VK, Sochor O, Lopez-Jimenez F. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10(3):234–44.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PG: preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Quality appraisal tools. Checklist for prevalence studies.joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html. Accessed 4 Jan 2019.

Assessing the quality of systematic reviews AMSTAR checklist. https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j4008. Accessed 4 Jan 2019.

Reilly JJ. Descriptive epidemiology and health consequences of childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19(3):327–41.

AlBlooshi A, Shaban S, AlTunaiji M, Fares N, AlShehhi L, AlShehhi H, AlMazrouei A, Souid AK. Increasing obesity rates in school children in United Arab Emirates. Obes Sci Pract. 2016;2(2):196–202.

Musaiger AO, Al-Mannai M, Tayyem R, Al-Lalla O, Ali EY, Kalam F, Benhamed MM, Saghir S, Halahleh I, Djoudi Z, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents in seven Arab countries: cross-cultural study. J Obes. 2012;2012:981390.

Al Junaibi A, Abdulle A, Sabri S, Hag-Ali M, Nagelkerke N. The prevalence and potential determinants of obesity among school children and adolescents in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Int J Obes. 2013;37(1):68–74.

Al-Hazzaa HM, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM, Alsulaiman NA, Musaiger AO. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity among urban Saudi adolescents: gender and regional variations. J Health Pop Nutr. 2014;32(4):634–45.

Musaiger AO, Al-Mannai M, Al-Haifi AR, Nabag F, Elati J, Abahussain N, Tayyem R, Jalambo M, Benhamad M, Al-Mufty B. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents in eight Arab countries: comparison between two international standards (ARABEAT-2). Nutr Hosp. 2016;33(5):567.

Reilly JJ, Kelnar CJ, DW Alexander B, Hacking ZCMD, Stewart ML, Methven E. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:748–52.

Diouf A, Adom T, Aouidet A, El Hamdouchi A, Joonas NI, Loechl CU, Leyna GH, Mbithe D, Moleah T, Monyeki A, Nashandi H, Somda S, Reilly JJ. Body mass index versus deuterium dilution for establishing childhood obesity prevalence across 8 African countries. Bull WHO. 2018;96:772-81.

Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of childhood obesity on adult morbidity and premature mortality: systematic review. Int J Obes. 2011;35:891–8.

Al Rashidi M, Shahwan-Akl L, James J, Jones L. Contributing factors to childhood overweight and obesity in Kuwait. Int J Health Sci. 2015;3(1):133–55.

El-Ghaziri M, Boodai S, Young D, Reilly JJ. Impact of using national v. international definitions of underweight, overweight and obesity: an example from Kuwait. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(11):2074–8.

Elkum N, Al-Arouj M, Sharifi M, Shaltout A, Bennakhi A. Prevalence of childhood obesity in the state of Kuwait. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(6):e30–4.

Kuwait Nutrition Survey: Ministry of Health (Kuwait). Annual Report 2016. https://www.moh.gov.kw/Renderers/ShowPdf.ashx?Id=62b5708c-d2fa-45a5-b677-c02632ac76a7.

Acknowledgments

The authors would to like to acknowledge the support of the Ms. Sarah Kevill, specialist librarian, for help with the literature searching; Dr. Anne Martin for providing the prevalence study critical appraisal tool; all the academics who responded to emails requesting comments on the literature search, and requests for grey literature in the GCC states.

Funding

Public Authority for Applied Education and Training, Kuwait; Kuwait Cultural Office; Scottish Funding council.

Availability of data and materials

Available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Initial study concept: JJR; Study design: both authors. Searching: HA. Eligibilty checking, Data extraction, Study quality assessment, both authors. Drafting of manuscript HA; Critical revisions of manuscript JJR. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Literature search terms in Medline. Search terms and syntax in Medline. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. GCC experts consulted on search findings and missing studies. Summary of experts contacted to check on search results, their affiliations, and their responses. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S3. List of excluded studies. Summary of full-text screened studies excluded, with reasons for exclusion. (DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Hammadi, H., Reilly, J. Prevalence of obesity among school-age children and adolescents in the Gulf cooperation council (GCC) states: a systematic review. BMC Obes 6, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-018-0221-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-018-0221-5