Abstract

This systematic review identifies factors that prior studies have identified as supporting the academic success of Latinx transfer students, who matriculate at 2-year institutions with respect to earning a 4-year baccalaureate degree in a STEM field. Since the students matriculate at a 2-year institution, they must, at some point in their academic career, transfer to a 4-year institution to earn the baccalaureate degree. Search and screening procedures identified 59 qualifying studies describing factors supporting persistence, transfer, or graduation of Latinx students matriculating at 2-year institutions. To synthesize findings, we coded the 31 quantitative, 22 qualitative, and six mixed methods studies according to unified themes. Nearly half the quantitative studies explored student characteristics alone, while some qualitative studies explicitly sought to identify assets Latinx students bring to higher education. None of the quantitative students utilized assets-based frameworks such as Yosso (Race Ethn Educ 8:69–91, 2005) to guide their analysis. All types of studies contributed to the conclusion that quality interactions with peers and staff support success of Latinx STEM transfer students. Specific details and strategies for institutions and their staff to support these interactions are described.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Projected science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workforce shortages are a concern in many countries (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, 2008; OECD, 2015) and global backlash against immigration is causing focus to shift toward developing STEM talent among citizens (e.g., National Academies, 2016). In the USA, one focus of efforts to develop STEM talent is students who trace their origin to Spanish-speaking countries including, but not limited to, Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Central and South American countries. This group, which we refer to as Latinx students, is underrepresented in the US STEM workforce but is rapidly growing in both the general population and in education. While the dynamics of diversity and inclusion are specific to each national or regional setting, efforts to develop STEM talent among STEM students are part of a larger worldwide movement for education to be more inclusive of cultural, linguistic, and intellectual diversity (e.g., Florian, 2012; Ferguson, 2008). This systematic review explores factors that influence Latinx students’ STEM bachelor’s degree attainment, through a particularly promising pathway where students matriculate at 2-year community colleges and transfer to 4-year institutions of higher education.

According to the US Census, the Latinx population in the USA is substantial and growing. By 2016, at 17.9% of the total population, Latinx persons became the largest racial or ethnic minority in the USA (Bauman, 2017). Similarly, in 2016, Latinx students made up almost a quarter of all people enrolled in K-16 institutions (Bauman, 2017), and Latinx students were the largest minority group enrolled in the nation’s 4-year institutions in 2012 (Fry & Lopez, 2012).

Evidence from the literature suggests that 2-year to 4-year transfer pathways are important to increasing the number of US Latinx students graduating with STEM baccalaureate degrees. Latinx STEM students enroll in public, 2-year colleges in higher proportions than any other group (National Science Foundation, 2015) and Latinx students account for 25.2% of traditionally aged students enrolled in 2-year colleges (Fry & Lopez, 2012). These students are more likely than other groups of students to enroll in programs that lead to transfer compared to technical or vocational programs (National Academies, 2016). Additionally, 2- to 4-year transfer pathways are particularly effective in increasing participation of Latinx students in STEM (Gándara et al., 2012). A study of thirty 4-year and fifteen 2-year US institutions confirmed higher proportions of Latinx students in engineering and pre-engineering programs in 2-year institutions than in 4-year institutions. It also suggested proportions of Latinx students among transfer student populations were higher than in student populations at 4-year institutions (Knight, Bergom, Burt, & Lattuca, 2014). In the MIDFIELD multi-institutional data set, 40% of all Latinx students who earned engineering bachelor’s degrees were transfer students, compared to 30% of white students (Camacho & Lord, 2013). Better understanding of these pathways for Latinx students could lead to increased student attainment of baccalaureate degrees for this underrepresented group. As described below, we argue that a systematic review is needed to analyze prior work, as well as to focus on the success of Latinx students matriculating at 2-year institutions and transferring to 4-year institutions to earn their baccalaureate.

Prior reviews focused on Latinx students in higher education informed this review. One emphasized the need for an empirical body of evidence to inform variable selection in longitudinal national data sets (Nora & Crisp, 2009). Others also considered only one success outcome (e.g., retention or graduation) which limited their scope (Oseguera et al., 2009; Padilla, 2007). Therefore, we have focused this review on factors influencing success of Latinx students and considered multiple outcomes that indicate their success. The most comprehensive review we identified used inclusion criteria that encompassed multiple academic success outcomes, and the authors synthesized research from several disciplines to explore the success of Latinx undergraduates (Crisp et al., 2015). Given the importance of the 2- to 4-year pathway, we have focused our study on Latinx students matriculating at 2-year institutions and included studies that examined students transferring to 4-year institutions.

Three concerns emerged from studying existing literature that guided our development of the research questions and framing of the discussion for this study. First, we found prior reviews, as well as studies identified in these reviews, tended to highlight factors hindering student success that were characteristics of individual students (e.g., students of lower socioeconomic status succeed at lower rates in higher education). This emphasis on characteristics of individual students depicts, often unintentionally, Latinx students as the primary agents of their academic failure or success and ignores broad societal and educational contexts. Latinx students are often placed into less rigorous educational tracks because of implicit biases (Meier & Stewart, 1991). Overreliance on the dominant culture in the construction of classroom environments and curriculum development (Ladson-Billings, 1995) and stereotype threat (Walton & Spencer, 2009) impede the academic success of pre-college Latinx students (Crisp et al., 2015). When these contextual factors are ignored and individual student factors that negatively influence success are emphasized in the quantitative analysis of large data sets, student traits can be perceived as deficits. Then, patterns of structural racism and other forms of oppression are ignored and suppressed (Camacho & Lord, 2013). Identifying individual challenges, absent institutional and cultural context, tends to promote a fix-the-students perspective that perpetuates inequities (Bensimon, 2005; Harper, 2010) or ignores possibilities for systemic institutional change. Instead, addressing historical inequities sustained by societal structures and educational systems requires institutions of higher education to transform to support increasingly diverse student populations (Bensimon, 2005; Harper, 2010). In response to what we perceived as an emphasis in the existing literature on characteristics of individual students, we focused our research questions, findings, and discussion on factors that institutions of higher education and their staff could influence as a precursor to transforming educational systems.

The second concern is that in reported findings, factors identified as hindering student success are often framed in terms of what students lack or deficits that need to be attended to, as mentioned in the previous paragraph. In contrast, Yosso (2005) called for approaches that focus on students’ cultural capital, or assets, to promote student success. An assets-based perspective, as used in this manuscript, focuses on attributes of students, their resources, and their contexts, on which initiatives to promote their success can build, as opposed to deficits that must be “fixed.” As an example of aspirational capital, Latinx students often have dreams “developed within societal and familial contexts, often through linguistic storytelling and advice (consejos) that offer specific navigational goals to challenge (resist) oppressive conditions” (Yosso, 2005, p. 77). Initiatives could build on dreams and specific student motivations instead of emphasizing efforts to “fix” students’ lack of preparation. Such assets-based perspectives offer compelling alternatives to deficit perspectives (Harper, 2010), which often recharacterize educational inequities as stereotypical traits based on race, ethnicity, a culture of poverty, and related factors (Bensimon, 2005). Interventions based on a deficit perspective typically identify a group of students with a specific deficit (e.g., low mathematics ability) and develop an intervention for this group. As a result, these interventions, based on our systematic review of interventions intended to support success of Latinx students (Martin et al., 2017), tend to be supplemental interventions designed to fix students. On the other hand, assets-based interventions build on dreams, specific student motivations, and students’ cultural capital. Since all students have dreams, motivations to succeed in higher education, and cultural capital, assets-based interventions tend to address all students, thus requiring institutional action (e.g., Brown & Kurzweil, 2017; Holloway, Reed, Imbrie, & Reid, 2014) and necessitating accountability among administrators, instructors and staff to produce equitable educational outcomes for all students. To address our second concern, we attempt to deemphasize deficit-based perspectives in reporting our findings by focusing on student experiences and factors institutions of higher education can influence.

The third concern is an overreliance on the Tinto (1993) model of student attrition, as well as similar models that have built on Tinto’s work (Crisp et al., 2015). A review of Tinto’s work and associated models is beyond the scope of this paper. Oversimplified, Tinto’s model and associated models focus on characteristics of individual students (e.g., goal commitments) and what individual students can do to improve success (e.g., assimilate to existing campus communities). Critiques of Tinto’s theory and other models based on his work focus on several points. First, these models emphasize individual characteristics and decisions influencing student success and deemphasize contextual factors that influence the academic success of students. This point has the same consequence of our first concern above, namely the choice of characteristics of individual students as factors to be studied, but the reasoning underlying the choice of factors to be studied is different. Second, although Tinto’s model has changed over the course of the 35 years from which it was originally introduced (Demetriou & Schmitz-Sciborski, 2011), critiques of the theory point out how Tinto defines students traditionally (e.g., full-time, 18–22-year-old students living on campus) and describes cultural assimilation to the dominant Eurocentric culture as the norm rather than promoting the evolution of campuses to value the distinct and diverse assets Latinx students bring from their cultural values and experiences (Crisp et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2018; Oseguera et al., 2009). Lastly, critics point out that the model separates necessarily entangled social and academic integration constructs (Lee et al., 2018).

In addition to these critiques, variations in how multiple studies have operationalized the theoretical constructs (i.e., social integration and academic integration) are problematic (Crisp et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2018). The operationalization is inconsistent from study to study and often defined one-dimensionally so that studies are unable to fully capture complex phenomena. Crisp et al. (2015) concluded that the absence of a cohesive theoretical framework throughout the literature makes it difficult for results to inform policy and practice. They therefore called for integration of Latinx students’ cultural values and experiences into theoretical frameworks focused on the assets within this population. Ultimately, the Tinto model depicts students as the primary agents determining their success and as such does not provide a framework for generating institutional actions (e.g., programs and policies) for improving academic success of Latinx students. To facilitate the development of such a framework, there is a need for literature that shifts the focus from individual students to institutions and their staff.

A systematic review could have multiple benefits in the development of this framework (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). First, a rigorously and transparently conducted review gives the reader an opportunity to assess the approach and conclusions. Second, systematic reviews provide a clear overview of a topic, presenting what is known and what is not known. Such clarity informs decisions when designing or funding future research, interventions, and programs. These reviews can clarify which factors evidence suggests have influence, which whose influence it does not support, and which require further study to guide future work. Finally, systematic review methods identify, capture, and synthesize the collective wisdom in primary studies with the populations and outcomes of interest (Borrego et al., 2014). To promote an assets-based perspective we will emphasize factors that institutions and their staff can influence to support bachelor’s degree attainment among Latinx students who enter higher education at 2-year institutions.

These questions guided this systematic review:

-

What factors, including factors that institutions of higher education can influence, factors related to influences of interactions with instructors and/or other staff, and factors over which an institution has little or no direct control (e.g., student characteristics), have prior studies identified as supporting the success of Latinx transfer students?

-

What are factors that institutions and their staff can influence? (Note: We included this research question since our study of existing literature suggested an overemphasis on student characteristics and the research question serves to highlight our emphasis on highlight other factors in our systematic review.)

-

What, if any, are the special considerations for STEM majors?

Method

Our systematic review relied on methods detailed by Borrego et al. (2014); Gough et al. (2012); and Petticrew and Roberts (2006) as described below. Systematic reviews are research syntheses that can vary in the types of studies combined, either only qualitative or quantitative studies, or they can integrate results from both types of studies. In the studies identified in this review, the success outcomes varied widely, and consideration of all types of empirical approaches were used to inform the review.

Our emphasis on Latinx students matriculating at 2-year institutions contrasts with prior reviews that focused on student success at 4-year institutions. Since there are few studies that addressed Latinx STEM transfer students, we included studies of transfer students of all race/ethnicities, Latinx students at 2-year institutions, and students at Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs). We defined success broadly, but traditionally, as persistence for at least one semester, transfer to a 4-year institution, or graduation from a bachelor’s degree program. We did not limit the type of study to those with quantitative evidence of student success. Many of the quantitative studies we reviewed follow the US Census terminology of Hispanic. For consistency, we use a single term (Latinx), while acknowledging that Latinx students are a heterogeneous group and that individuals may prefer other terms based on their geographic and political backgrounds (Camacho & Lord, 2013).

Search procedures

Foster searched several databases with agreed-upon search terms to retrieve relevant studies. These databases included ERIC (Ebsco), Academic Search Complete (Ebsco), and Compendex (Engineering Village). The search included the concepts (STEM or engineering or Latinx) and (transfer) and (two-year college) as well as synonyms and thesaurus terms for each concept. Foster constructed the ERIC search syntax before translating it for following database searches. The search spanned January 1, 1980, to June 24, 2016, the date it took place. All records were exported to RefWorks (Refworks, n.d.) and duplicates were removed. Scopus was used to locate references to highly related studies and included studies.

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion in this review, studies must have included the following characteristics:

-

Student population: Latinx students enrolled in 2-year institutions, students in 2-year Hispanic-serving institutions, or 2- to 4-year transfer students; US institutions only

-

Success outcome: Transfer, retention, graduation, satisfaction, financial aid/knowledge, and success in one course or one semester

-

Format: Report, journal article, conference paper, or dissertation in English published since 1980, when US Census procedures changed how they reported Latinx respondents (Cohn, 2010)

-

Evidence: Quantitative and/or qualitative, empirical evidence connecting a factor to its influence on one or more of the identified student outcomes

To determine the selection of studies from the search results, Foster randomly assigned two authors to read each study and answer a series of questions using Qualtrics web-based survey software. The questions addressed both eligibility criteria and characteristics of the study. We resolved disagreements through discussion and then divided the studies based on their methods.

Coding and quality assessment

Two researchers independently coded each of the quantitative studies using the online Qualtrics form. After coding a subset of quantitative studies, the two authors met to review how they coded each study. If they disagreed on coding an aspect of a study, they reviewed the study and reached consensus on how to code the aspect of the study. They repeated this process until they reached consensus on coding each aspect of the study. Since there were many aspects of each study, they did not track disagreements on an aspect-by-aspect basis, so the frequency of disagreements was not recorded. The following characteristics were coded:

-

Type of resource: Report, journal article, conference paper, or dissertation

-

Population: Latinx or students at HSI, Black or other minority, women, STEM majors, transfer students, 2-year institution, and single or multi-institution

-

Results: Factors considered and success outcomes

After initial coding, Froyd and Winterer collected more detailed information by organizing all significant factors from each quantitative study and the specific data sources used in the study into a comprehensive spreadsheet. All authors collaborated to produce a quality score rubric (Table 1) for quantitative studies. The rubric produced an overall quality score between 0 and 7 points by evaluating aspects of the study design including number of institutions, sample size, longitudinal or cohort data, and sophistication of statistical analyses.

The selection of the criteria was based, in part, on recommendations for educational research (Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy, 2007; Towne & Shavelson, 2002; Turner et al., 2013). We considered these recommendations and the context of our sample to develop a scoring system that, in general, awarded higher scores to studies that were more generalizable, as generalizability is an expectation of quantitative research. For example, we awarded points to studies that included multiple institutions and larger sample sizes as these factors would likely lead to more generalizability. The specific sample size in criterion 2 was chosen because a review of the sample sizes in the identified studies showed the number chosen was a demarcation between smaller and larger sample sizes. Studying the same participants over time (e.g., a longitudinal study) would also more likely yield generalizable results compared to studies that only consider participants at a single point in time. Further, studies that considered multiple factors simultaneously (e.g., regression, correlation) would likely yield more generalizable results than studies that only considered one factor at a time (ANOVA or t test). Although criterion 4 does not list all possible quantitative analysis approaches, the authors thought it provided sufficient distinction between the approaches found in the identified quantitative studies. Finally, as it is an accepted practice, we believed studies that explicitly acknowledged limitations would be more likely to yield generalizable results compared to studies that did not. Based on these considerations, the authors generated the quality appraisal scheme in Table 1.

Martin coded the qualifying qualitative studies for the following characteristics: study population, one or multiple institutions, research purpose, and major findings. Martin evaluated these studies to produce a quality score of “low,” “medium,” or “high” by assessing their adherence to Guba and Lincoln’s (1989) authenticity criteria: fairness, ontological authenticity, educative authenticity, catalytic authenticity, and tactical authenticity.

The screening and selection process identified six mixed methods studies. Borrego coded these studies for study population, one or multiple institutions, research purpose, and major results. The quality assessment of these studies was based on criteria for mixed methods studies (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007), which included (a) distinctive quantitative and qualitative approaches; (b) mixed methods, designs, visualizations, and citations; and (c) mixing quantitative and qualitative data. Scores were generated by giving two points for each of the three items, for a maximum score of six points.

To synthesize results across studies and make meaning of the factors, we created categories. We started with categories based on findings we synthesized from the qualitative studies. Then, we identified common statistically significant factors from the quantitative studies. We aligned the quantitative and qualitative categories where possible and created new categories as needed. We repeated this process for the mixed methods studies. Then, we grouped the categories of factors into Tables 3, 4, and 5 using the rationale described below.

Limitations

Several limitations of this approach should be noted. Our list of qualifying studies may not be complete. Omitted studies may be unpublished, not indexed in the databases we used, or otherwise not captured by our search parameters. Additionally, we excluded many studies about the success of Latinx students in 4-year institutions if we could not readily identify that they included transfer students. We may have omitted some studies that included transfer students, albeit not prominently enough. Our procedure of separating intervention studies for a different analysis and publication may have deemphasized certain factors, such as teaching, which can be framed either as a specific intervention or more generally as a factor. Additionally, the broad scope of this review does not address aspects of intersectionality that may influence the success of students. For example, the experiences of Black or Latina women in engineering may diverge from these findings. We also do not include student populations that begin their postsecondary education at 4-year institutions.

Results

Sample

Figure 1, modeled after Knobloch et al. (2011), illustrates the number of studies flowing through the initial search, selection, and coding process. After an initial search yielded 2732 results, we included 170 studies for analysis. Of these, 74 studies examined interventions related to specified success outcomes and were included in a previous paper (Martin et al., 2017). From the 96 remaining studies that did not examine interventions, we identified 59 studies that met all inclusion criteria and addressed factors related to student success outcomes.

We excluded studies as irrelevant that the original keyword search had identified for varying reasons. The search string necessarily included some general terms to identify studies of transfer students. As a result, the search returned many papers that used these terms in other ways (e.g., heat/mass transfer, transition state, knowledge transfer). We also excluded many state and institutional reports of student enrollment disaggregated by ethnicity because they did not address any outcomes of interest. Other common reasons for excluding studies included examination of the wrong population, no documented methods, and lack of evidence supporting assertions in the study.

Table 2 summarizes the study populations across quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. In the results sections that follow, quantitative studies labeled “high” earned a score of 6 or 7, “medium” earned 4 or 5, and “low” earned 1–3 points.

One notable and somewhat surprising result reported in Table 2 is that only two of the studies were specifically about Latinx STEM transfer students. However, an effective synthesis of all 59 studies can provide a foundation for current action and future research for this specific population. Relevant insight can be gleaned from considering studies that investigate Latinx student success, more generally, as well as ones that investigate STEM transfer success specifically. First, a key to studying success of Latinx STEM transfer success is that students must be successful in 2-year institutions before transfer. Many of the studies identified in Table 2 focused on experiences of Latinx students in 2-year institutions and contribute useful insights. Further, in many studies of Latinx students in 2-year institutions, students are not specifically identified as STEM majors or not. If all participants in a study were all in non-STEM majors, we excluded the study. However, we did not exclude studies in which we were unable to discern if the study participants were STEM or non-STEM majors. Therefore, we included studies shown in the second, third, and sixth rows in Table 2. Further, studies of transfer students that included Latinx students, but did not focus on solely on Latinx students, offered valuable findings, as well. Therefore, we included studies shown in the fourth and fifth rows in Table 2. Although we identified only two studies of factors influencing success of Latinx STEM transfer students specifically, findings from all 59 studies shown in Table 2 offer valuable insights for synthesis.

As discussed previously, student experiences (e.g., peer relationships and quality of advising) that are likely to be independent of academic major often influence student success outcomes. Therefore, our systematic review includes factors influencing academic success common to the majority of Latinx students regardless of their major. In addition, we included studies that considered factors influencing students’ matriculation at 2-year institutions (e.g., success in writing, mathematics, and science courses as well as developmental courses in these subject areas) that are important to success of all students in the 2-year institutions. The findings from these studies are important to our consideration of factors influencing success of students that matriculate at 2-year institutions because students must be successful at 2-year institutions, successfully transfer, and successfully complete curricula at 4-year institutions to earn a baccalaureate STEM degree.

Therefore, our review synthesizes findings from the 59 studies in Table 2 to facilitate translation, synthesis, abstraction, and application of these results for Latinx STEM transfer students. Our discussion calls for structural changes to be made in higher education institutions to benefit all Latinx students matriculating at 2-year institutions, including those majoring in STEM disciplines. Some of these changes can be implemented at 2-year institutions, some can be implemented by partnerships between 2-year and 4-year institutions, and some can be implemented by 4-year institutions. All of the changes will, we argue, contribute to the success of Latinx students matriculating at 2-year institutions who will need to transfer and be successful at 4-year institutions to earn baccalaureate degrees in STEM majors.

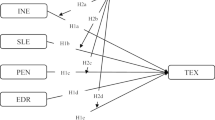

Tables 3, 4, and 5 present synthesized results across all 59 studies, separated by the entity that influences student success—institutions (Table 3), instructors and other staff (Table 4), and students and their families (Table 5)—and the factors identified using qualitative or quantitative data. Results from mixed methods studies were separated into qualitative and quantitative results. A blank cell in a table shows that we did not identify any studies using data of that type that supported the influence of a particular factor. As noted, an asterisk indicates a mixed methods study and a dagger indicates studies focused on STEM students.

Institutions

Table 3 focuses on factors that institutions of higher education can influence to support the success of Latinx students who matriculate at 2-year institutions. It shows eight factors in order of decreasing number of studies: peer interactions, cultural climate, advising, coursework articulation, academic integration, support services, assets-based factors, and outreach. Fifteen of the 31 quantitative studies, 20 of the 22 qualitative studies, and one of the six mixed methods studies presented findings in one or more of the eight factors related to institutions. All but two of the 20 qualitative studies were published after 2010, suggesting that qualitative inquiries focusing on factors that institutions influence to support the success of Latinx students is a recent trend.

Peer interactions

The success factor that the largest number of studies (8 qualitative and 6 quantitative) supported was peer interactions, which quantitative studies sometimes included as part of the “social integration” variable (Crisp et al., 2015). Peer interactions included participation in school organizations, social integration, and supportive peer relationships. Quality of the studies supporting peer interactions ranged across our quality scale, with approximately half of the studies scoring high. Fourteen studies overall, including six high-quality studies, provide strong evidence that improving peer interactions at an institution would likely improve success of Latinx students.

Quantitative studies can identify the significance of factors but not processes through which these relationships influence student success. The qualitative studies help to develop a deeper understanding of the nature of the processes. Participants in qualitative studies acknowledged peer relationships as a vital component to both their academic success and emotional well-being (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Dorame, 2012; Patterson, 2011; Wade, 2012). They commonly expressed gratitude for deep friendships that developed from time spent in study groups or working with other students in a class. However, students found that they needed to be strategic in choosing peers with whom to collaborate. Some cited the importance of choosing friends who are supportive of them pursuing an education (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Prado, 2012), while others were drawn to students with similar backgrounds and experiences (Allen & Zhang, 2016; Wade, 2012). Students reported peers can influence important decisions such as choice of major, degree aspirations, and persistence in their course work (Dorame, 2012; Martin et al., 2013). Peer relationships can validate students’ STEM identity and provide them with a sense of community to support their academic performance and motivation to persist (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Martin et al., 2013). Overall, these studies suggest that forming resilient peer relationships could positively impact students’ trajectories as these relationships play such a significant role in their success.

Studies also identified barriers that could make it difficult for students to develop relationships and have productive peer interactions. For example, if there are few students with a similar background in a course or at the institution, it may be difficult for underrepresented minority students to form a project group (Wade, 2012). Transfer students also reported having a difficult time finding and/or maintain a study group because established groups were difficult to enter and connections dissolved due to inconsistent enrollment (Prado, 2012; Patterson, 2011; Wade, 2012).

Cultural climate

Cultural climate included factors such as diverse student population (i.e., racial representation of the student body, in three high-quality quantitative studies), accessible instructors, affordable tuition, engagement with institutional agents, students’ cultural affinity (perception they belong at institution), acculturative stress (one mixed methods study), and the number of Latinx instructors at 2-year institutions. Among the quantitative studies supporting cultural climate, four of the seven were high quality and the rest were medium, indicating the support from quantitative studies was strong. All five qualitative studies were low to medium quality. In summary, 13 studies support the strength of the influence of cultural climate, but the quality of the studies varied.

In multiple qualitative studies, students reported an expectation at their institution that they should know all rules and policies for navigating the system (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Jackson, 2013a). Students met this expectation by leaning on peers, administrators, or a previously acquired basic understanding of procedures of the 2-year college (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011). Smaller class sizes supported student success. Students reported feeling less pressure and greater comfort practicing conversation and academic speaking skills in small rather than larger classes (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011). Students reported feeling comfortable at 2-year colleges and universities where their race/ethnicity is well-represented. In Alexander et al. (2007), Latinx students expressed apprehension about transferring to predominantly white institutions. Because these students had spent little time in predominantly white communities, they worried they would struggle to fit in on a mostly white campus. They saw their 2-year college with a large Latinx population as an extension of their community. Jackson (2013a) reported a similar finding for African American STEM students transferring to a historically black institution, which they described as a safe space to develop their STEM identity.

A few studies described aspects of campus or classroom climates that can be difficult for transfer students to navigate. One transfer student who had positive experiences with 2-year college instructors described a “chilly climate” in a 4-year university STEM course. She explained that when she asked questions, her peers ignored her, and the instructor did not intervene or make her feel supported. This led her to participate less. A second student also felt like some of her university professors did not like to answer questions and did not consider teaching a priority (Jackson, 2013b). In Coley and Vallas (2015), a student recounted an experience in class where non-transfer students drew upon previous knowledge to complete a task. As a transfer student, he lacked this knowledge and had trouble with the assignment. It emphasized how much he had missed in comparison to the non-transfer students and his feelings of disconnection from his cohort. Other transfer students in the same study described that if they came in during their third year, all the non-transfer students are already connected. This leads the transfer students to form their own study groups when they have the same course. Transfer students also expressed that starting over with a 0.00 GPA after transfer, in their third year when classes are the most difficult, creates a climate of extreme pressure in the transfer student community.

Advising

Influence of advising/counseling on success of Latinx students was supported by 11 studies (eight qualitative and three quantitative). Qualitative studies (all high or medium quality) focused on how students perceived and/or experienced advising, which quantitative studies could not provide. Among these, six support a finding that students perceive advising support as important to their outcomes. While advising can support student success, three qualitative studies report that variability in how students experience the quality of advising services can negatively impact their aspirations or delay transfer or matriculation. Quantitative studies (two of the three were high quality) showed that the quality and frequency of advising were positively correlated with perceived success with respect to outcomes. The number of studies and the overall quality of both the qualitative and quantitative studies supporting influences of advising indicates that improving advising experiences for Latinx students would likely yield improvements in student outcomes.

Multiple qualitative studies showed students recognized the importance of academic advisors in navigating higher education (Arteaga, 2015; Jackson, 2013b; Sayasenh, 2012). This was especially true for first-generation students, who may not be able to rely on their families for guidance (Arteaga, 2015). All of the 26 first-generation, low-income, Latinx 2-year college students who participated in the Arteaga (2015) study reported relying on counselors for guidance in many areas beyond course selection, including when to register for classes; preferred instructors; developing a plan to reach their educational goals; referrals to campus resources such as financial aid, child care services, and tutoring; help with both personal and college applications (e.g., financial aid, housing, and unemployment); advice regarding personal issues; and validation or encouragement. Advisors can provide students with invaluable resources and offer needed guidance. Students credited advisors for their persistence in their degree aspirations (Dorame, 2012; Jackson, 2013b; Sayasenh, 2012). Students reported that the support of advisors can remove a significant amount of pressure, enabling them to focus on their coursework (Dorame, 2012; Jackson, 2013b; Sayasenh, 2012).

Qualitative studies also described detailed accounts of negative advising experiences (Packard et al., 2012; Patterson, 2011; Ramirez, 2011; Wade, 2012). Students described being disappointed with advisors who read directly from course catalogs, could not answer their questions, referred students to multiple advisors, or gave students standardized and confusing guides to direct their course selection (Patterson, 2011; Wade, 2012). Packard et al. (2012) organized negative advisor actions into two categories: poor advising and passive advising. Poor advising includes advising students to retake courses they already passed, counseling them to take courses that would not transfer, and encouraging students to complete an associate degree before transfer even though the degree is not required. Passive advising practices included not informing students they could retake math placement tests to improve their scores, omitting important information about how similar courses would transfer differently, and failing to refer students to an appropriate resource when they were unable to answer the question. Low-quality advising left students to problem solve on their own. They self-advised by using the internet, relied on peer advising, or sought advising from department instructors or other staff, who may not be familiar with the intricacies of transfer credit policies (Patterson, 2011; Wade, 2012). In Wade’s (2012) study of eight STEM majors, students who had negative advising experiences and could not access a network of information generally did not complete STEM degrees.

Academic integration

Several models of retention and/or persistence connect academic integration with student success (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1980; Spady, 1970; Tinto, 1993). As noted in the “Introduction” section, many conceptualizations of academic integration that stem from Tinto’s (1993) work can be conceptually and practically problematic, especially for non-traditional students (i.e., not full-time, 18–22-year-old students living on campus) (Crisp et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2018). Academic integration considers the degree to which a student engages with the academic elements of the institution, including study groups, learning communities, social contact with instructors, meeting with academic advisors, and academic conversations with instructors. For these studies, academic integration meant student engagement in tutoring, study groups, or learning communities; engagement with instructors inside or outside of class; students’ perception or frequency of interactions with instructors; or meeting with an academic advisor.

Academic integration was a factor in four quantitative studies and three qualitative studies. The quality score of the seven studies supporting influences of academic integration varied considerably, with one of the quantitative studies being low quality, two of the quantitative studies and two the qualitative studies being medium quality, and the remaining studies, one qualitative and one quantitative, being high quality. Based on this, academic integration has moderate support for influence on success of Latinx students, though the way it is operationalized that may not consider the personal circumstances and cultural contexts of Latinx students.

In qualitative studies, academic integration overlapped with other factors, such as peer interactions, instructor-student interactions, and advising/counseling, revealing the intertwined nature of these factors. Qualitative studies identified resources and relationships that supported students’ academic integration, including tutoring centers, student organizations, on-campus jobs, study groups, counseling, interaction with instructors, and learning communities (Patterson, 2011; Sayasenh, 2012; Wade, 2012). In all three studies, students mentioned tutors or study groups as a positive influence. Wade (2012) found that students who did not have a peer mentor often relied on study groups for integration into the STEM community. Patterson (2011) found women transfer students considered the lack of tutoring centers at their 4-year colleges to be a problem for multiple reasons. First, they had relied on such centers at their 2-year colleges not only for tutoring but also as a gathering place to find peer support. Second, they found networking with non-transfer students difficult. Patterson (2011) explained transfer students wanted to join study groups but found networking with non-transfer students difficult, since these students had already established peer networks, which were difficult for transfer students to enter.

One theme that was only articulated in Wade (2012) was that study participants felt like they needed to “earn their place” in the STEM community. All minority students “described experiences in which the lack of recognition, embodied by feeling excluded, the inability to find study partners, or the discomfort they experienced in class or in teacher’s offices, impacted their STEM experience” (p. 69). Relationships with peer mentors helped students navigate these difficult social and/or academic experiences. Students who did not have a peer mentor integrated into the STEM community through student organizations, on-campus jobs, or study groups.

Support services

In addition to the 11 studies on advising/counseling, seven studies included a broader definition of support services. Qualitative studies mentioned tutoring centers, computer labs, and even student health services. Students who were unaware of these services or who had difficulties in accessing them had a higher likelihood of negative outcomes. Two quantitative studies included support services along with student perceptions of belonging to the institution and campus climate as factors correlated with positive student outcomes. However, all but one of the five qualitative studies were medium or low quality, and the two quantitative studies were of medium quality. As a result, we conclude the evidence for support services influencing student success as defined in this review is not compelling.

Coursework articulation

Seven studies, a moderate number in the context of this review, suggest coursework articulation and/or statewide transfer guides support the success of Latinx students. Of these, two were high-quality qualitative studies, four were medium quality, and one was a high-quality quantitative study. Five of the qualitative studies and the quantitative study focused on STEM-specific populations. In general, articulation agreements and transfer guides document which courses at 2-year institutions transfer to which courses at 4-year institutions. Sometimes they indicate whether credits that transfer to a 4-year institution also count toward completion of a degree program at a particular 4-year institution. We find the literature support for articulation agreements and transfer guides encouraging, but not compelling, because of the relatively small number of studies.

Although the overall evidence for articulation agreements and transfer guides is not compelling, the authors wanted to highlight institutional practices that could help students feel supported and successful at their 4-year institutions after transfer. These practices were identified in one qualitative study (Jackson, 2013a). This study described how instructors and advisors from both 2-year and 4-year institutions worked together to suggest students retake particular courses when key concepts were missing from the previous course. STEM students credited consistent information from various institutional agents at both the 2-year and 4-year institutions with supporting their success in transferring because it relieved anxiety and facilitated transition to the university culture. Consistent messaging combined with smooth transfer of credits signaled to students that their institutions were communicating with each other and working as a team to support their success.

Assets-based frameworks

Three qualitative studies specifically focused on assets that Latinx 2-year college students bring to higher education, guided by the Yosso (2005) community cultural wealth framework of forms of capital that students of color draw upon to achieve academic success. The studies show how these forms of capital, on which an institution could choose to design its overall student support program, support success of Latinx students. All the qualitative studies were published after 2011, and there was one each of high, medium, and low quality. We did not find any quantitative studies as clearly focused on assets. Thus, we would describe the evidence for influence of forms of capital in the community cultural wealth framework on Latinx student success as underdeveloped. The authors think that more research is needed on this topic.

Outreach

Two qualitative studies (Dorame, 2012; Matos, 2015) addressed the effectiveness of outreach efforts to increase student knowledge of the opportunities higher education affords. They show that such efforts benefit transfer students if they (a) occur by middle school and (b) involve students’ families and their communities. Given the small number of studies, evidence for effectiveness of outreach efforts is inconclusive. There is a substantial literature base focused specifically on outreach, which is beyond the scope of this review because it does not involve transfer students.

Higher education instructors and other staff

Table 4 summarizes factors extract from the 24 studies that examined influences of interactions with instructors and/or other staff at either 2- or 4-year institutions. These factors fell into two categories: (a) interactions with instructors and/or other staff, the broader category, and (b) teaching, a more restricted category of interactions. All 24 studies, the largest number supporting any factor in this review, suggested these factors support student success. There are 14 qualitative studies, all published after 2001 and all but three of high or medium quality; eight quantitative studies, six of which were published after 2010, and all but one of high or medium quality; and two mixed methods studies.

Staff interactions with students

Relationships with instructors were important to students and qualitative studies showed they positively or negatively influenced students’ academic performance and degree aspirations. Fourteen qualitative studies indicated students benefitted from instructors who were invested in their learning, caring, engaging, and personable. Interactions that communicated these characteristics often occurred outside the classroom, as well as within. For example, a student working full-time remembered an instructor who went out of his way to offer tutoring sessions after noticing a dip in her grades (Ramirez, 2011). Students were motivated by instructors they perceived to be invested in their learning and cited this instructor support as a major contributor to their academic success (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Sayasenh, 2012). From qualitative studies describing positive influences of instructor interactions, many students received individual attention while enrolled in 2-year institutions and perceived these instructors as more available and approachable than 4-year instructors (Coley & Vallas, 2015; Jackson, 2013b; Patterson, 2011; Zhang & Ozuna, 2015). Reasons may include smaller class sizes at 2-year institutions and demands on instructors at 4-year institutions beyond their teaching commitments (Coley & Vallas, 2015; Zhang & Ozuna, 2015).

Student appreciation for “caring” instructors appeared in several studies; however, ways in which students perceived instructors as caring varied (Arteaga, 2015; Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Dorame, 2012; Dowd et al., 2013). Some students described instructors who demonstrate they are invested in their students’ learning and make extra efforts to support their success as caring. This extra effort included making themselves available to students or being sensitive to an individual student’s needs or situation (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011). Other instructors had high expectations for students, encouraged students’ academic interests, and nurtured their confidence. Students reported high expectations coupled with support encouraged their degree aspirations (Dowd et al., 2013). Demonstrating caring does not always require significant effort. Students reported instructors were caring if they simply asked, “how are you?” and listened to the response (Patterson, 2011).

Students emphasized that instructors can help them build self-confidence and positively influence their ambition to earn a degree (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Dorame, 2012; Dowd et al., 2013; Jackson, 2013b; Zhang & Ozuna, 2015). While peer interactions and advising support students, instructors are exceptionally situated to help students overcome a sense of inadequacy (Dowd et al., 2013). As little as a single, encouraging conversation with an instructor can make students feel capable and affirmed that they could succeed in college (Dorame, 2012). Just having a helpful, knowledgeable instructor who is enthusiastic about his or her field can increase students’ interest in a subject and motivate them to raise their degree aspirations (Dorame, 2012; Ramirez, 2011). When professors take the time to ask students about their degree aspirations and advise or encourage them, students perceive recognition of their potential (Dorame, 2012; Dowd et al., 2013). Validation and/or encouragement from an outside, authoritative source builds student confidence and positively influences students’ degree aspirations (Dorame, 2012; Dowd et al., 2013; Jackson, 2013b; Zhang & Ozuna, 2015). Studies also indicated that instructors explicitly advising students on the process of transfer can positively influence their degree trajectory (Dowd et al., 2013; Ramirez, 2011). Additionally, providing students access to education information/resources or insights into how to navigate through a specific field (e.g., engineering) can influence their motivation to persist or raise their degree aspirations (Dowd et al., 2013; Jackson, 2013b; Zhang & Ozuna, 2015).

Unfortunately, instructor-student interactions have also been described as demotivating or uncomfortable experiences. For example, professors’ actions can make students feel like they are wasting instructor time or that instructors do not feel students are smart enough to be in the class (Wade, 2012). Students also said they were intimidated by some instructors. A combination of expert knowledge and a “professional and serious” demeanor of some instructors made them seem less approachable (Prado, 2012, p. 97). This lack of approachability made students less likely to ask questions during lectures and more likely to seek out help from peers rather than these instructors.

Cejda and Hoover (2011) provide useful strategies from instructors to help avoid these negative interactions with students. They conducted roughly 40 instructor interviews at three 2-year colleges focused on serving Latinx students. These instructors noticed their students often relied on each other for help to avoid approaching the instructor. They concluded they needed to establish trust with students, so they would ask for assistance. Instructors also engaged with students outside class by initiating casual conversations or attending social or cultural events. This approach helped establish a sense of trust that often extended into the classroom. Instructors also acknowledged the importance of learning about Latinx culture and publicizing information about academic support programs, financial aid, and other programs (e.g., child care, transportation) to support student success.

Teaching

Influences of teaching were supported by significantly fewer studies than staff interactions; just five qualitative studies supported this factor. Three studies found that instructional strategies positively influenced student outcomes if they promoted peer interactions, for example, through group work, student-led instruction, and student-centered instruction. In one study, students credited instructors who clearly spent a lot of time preparing for class and creating materials with supporting them (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011). Students also described needing an organized classroom where the instructor had a clear plan, shared class goals with their students, and worked to make sure students understood the material being presented (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011). Instructors also described actions they took in class to help students form learning communities. These included instructors facilitating explicit class discussions emphasizing standards and expectations, expressing their willingness to work with students outside of class, and dedicating time in class for students to organize their study groups (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011).

First-generation, English language learners reported having difficulty communicating with their instructors. Instructors confronted with this communication issue implemented several strategies, including using an interpreter, searching for texts in students’ native language, and allowing them to speak or write in their native language (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011Students who needed to learn English also noticed that professors in courses other than English seemed to be bound by a time-sensitive curriculum and did not always thoroughly explain concepts before moving on to the next (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011).

Two qualitative studies, one in which students were interviewed (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011) and one in which instructors were interviewed (Cejda & Hoover, 2011), showed culturally responsive teaching and/or relevant curricula that echoed students’ own experiences increased student interest in the course and positively influenced Latinx student engagement and outcomes. Participants in both studies noted that instructor practices focused on encouraging students positively impacted student experiences. For example, frequent feedback that is formative and constructive helped students prepare for summative assessments, and instructors also reported allowing students to revise and resubmit formative assessments multiple times (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Cejda & Hoover, 2011). Instructors tried to focus their feedback on suggesting areas for improvement rather than any shortcomings in student work.

Calling on students in class before they were comfortable could be demotivating for students (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011; Cejda & Hoover, 2011). To help students feel prepared to participate in class, instructors reviewed previous concepts before presenting new content and gave students time to reflect on or discuss concepts before asking for questions (Barbosa and Seton Hall University, 2011). In describing instructional practices that they found effective, instructors also remarked on the wide variation among Latinx students’ experiences and preferences (Cejda & Hoover, 2011).

Students, their families, and their communities

Table 5 presents 14 factors that are fundamentally different from the factors presented above. Tables 3 and 4 summarized factors over which institutions have some control, for example, advising and teaching. In contrast, Table 5 lists factors over which an institution has little or no direct control, or which might be at odds with their mission to serve specific communities.

Ten quantitative studies and one mixed methods study showed that one or more of these factors were, but should not be, predictive of student success: race/ethnicity, gender, age, starting at a 2-year institution, and citizenship status. This suggests the education system is not serving all students equally. We will not elaborate on these factors.

From a deficit-based perspective, the eight other factors in Table 5 can be interpreted as student deficits that must be addressed or ways in which students must be “fixed” to improve their success. These factors include the following:

-

Preparation, the lack of which can be construed as a characteristic of students who do not belong in higher education

-

Characteristics of the region or institution, which can be construed as characteristics of students coming from economically disadvantaged communities and institutions who do not belong in higher education

-

English competency, the lack of which can be construed as a characteristic of students who do not belong in higher education

-

First-generation and family support, which can be construed as characteristics of students without sufficient social capital to understand the relevance of higher education or the knowledge to navigate the pathways to success in higher education

-

Finances, the lack of which can be construed as a characteristic of students without necessary financial resources to attend college

-

Work/family obligations, which can be construed as a characteristic of students who must attend to needs other than focusing on work necessary to succeed in higher education; and

-

Goals, which can be construed as a characteristic of students without sufficient aspirations and focus to succeed in higher education

Conversely, these factors can be interpreted as evidence that higher education institutions are currently not designed to serve these students who are entering the higher education system. From our assets-based perspective, we feel the factors that appear in Table 5 can result in student strengths that higher education structures sometimes fail to utilize. For example, the experience of balancing work, family obligations, and course work could help students’ build skills around time management and organizing priorities, skills that would undoubtedly benefit them throughout their lives. However, the inflexibility of many structures within higher education makes it difficult for students whose circumstances require them to work. Therefore, we have chosen to focus our discussion on Tables 3 and 4 to develop conversations centered on actionable change and shifting institutional structures.

Finally, there are two factors in Table 5 that are different from many of the other factors in Table 5 as well as being different from the factors in Tables 3 and 4. So, in some ways they do not fit into any of the three tables. The first of these two factors is labeled “Credits.” This factor summarizes findings that the more credits that a student has completed, the greater the likelihood of student success. The second factor is labeled “STEM.” Since this is a study of factors influencing the success of Latinx transfer students in STEM fields, some elaboration may be justified. As shown in the table, the finding collects three results from quantitative studies. First, completing STEM courses correlates positively with student outcomes (Chen and Soldner, 2013; Kruse et al., 2015; Myers, 2015; Wang, 2015). This is consistent with the previous finding (“Credits”) that the more courses a student completes and or transfers, the higher the likelihood that students will achieve positive outcomes. The second and third results are very specific results, each from a single quantitative study and the text in Table 5 is sufficient to explain the results.

Discussion

We reviewed the multiple factors that influenced success of Latinx students who matriculate at 2-year institutions. Although we found some quantitative studies focused on student characteristics traditionally framed as deficits, we identified 11 factors (Tables 3 and 4) that institutions, their instructors, and their other staff can influence to support Latinx students and build on the assets they bring to 2-year institutions and to 4-year institutions as transfer students. Specifically, the interactions that students have with peers, advisors and other academic staff, and their instructors are critical to their success. Students benefited from instructors and advisors who cared about them as individuals, engaged them, motivated them, helped them increase their self-confidence, helped them improve their emotional well-being, believed in them, supported them in dealing with difficult issues, and conveyed that they could be successful. The ability to form study groups (or join existing study groups in the case of transfer students) was an important mechanism for peer support. The importance of study groups identified in this study echoes findings from prior studies (Dennis et al., 2005; Llopart & Esteban-Guitart, 2018; Ovink & Veazey, 2011). These findings are consistent with prior reviews, especially those that critique Tinto’s model. Given the importance of interaction with peers, instructors, and staff to the success of Latinx and transfer students, we found evidence that researchers need to develop more sophisticated conceptualizations of academic and social integration to guide future research and influence practice (e.g., Lee et al., 2018).

This review comes to many of the same conclusions of prior reviews (Crisp et al., 2015). In addition to overreliance on Tinto’s conceptualization of academic and social integration, we identified many of the same categories of factors. Additionally, we contribute to the literature by showing that these same factors are indeed relevant to Latinx students enrolled at 2-year institutions, Latinx transfer students, and Latinx STEM majors, as well as critiquing the quality and theory in prior studies. We also show that Latinx STEM transfer students are still an understudied population. Further, we advance scholarship in this area by framing the results to highlight an assets-based perspective on supporting Latinx STEM transfer student success. We found evidence of greater emphasis on assets, including community cultural wealth theory in particular, in the qualitative studies.

Including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies in our systematic review enabled multiple benefits of triangulation (Greene et al., 1989). We were able to clarify which factors are supported by both quantitative and qualitative results, as well as a few gaps (Tables 3, 4 and 5). We further validated many of the findings of individual studies. While the quantitative studies highlight the extent to which these factors influence student success, the qualitative studies illustrate how these factors operate. Several patterns emerged from the qualitative studies that illuminate the ways these interactions influenced student experiences. One very important gap identified here is in moving from a deficit to an assets-based perspective, especially when quantitative methods are employed.

A large proportion of studies focused on student characteristics. A sizeable minority, 34% (20 of 59) of all studies, including a slight majority, 52% (16 of 31), of quantitative studies appeared only in Table 5 (student, family, and community characteristics). This suggests quantitative studies tend to neglect factors related to institutional structures or faculty and staff. The Beginning Postsecondary Survey (BPS) used in several studies comprises detailed transcript, financial aid, institution type, and student and family characteristics data (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.). While these longitudinal data are invaluable for tracking transfer students through multiple institutions, the nature of the items tends to reproduce a deficit approach to studying students from underrepresented backgrounds. Specifically, they do not include psychosocial measures and detailed questions about academic experiences or interactions (Crisp et al., 2015) that would further validate our main findings. The Science Study (Schultz, Woodcock, Estrada, Hernandez, Quartucci, Rodriguez, et al., n.d.) is a step in the right direction; this US national, longitudinal study of 1400 minority science students, asks questions about stereotype threat, ethnic identity (Irizarry & Hunt, 2016), and mentorship (Estrada et al., 2018). Similarly, Hurtado’s work was excluded from Crisp et al.’s (2015) prior review because it did not focus on “traditional” outcomes but instead on sense of belonging (Hurtado & Carter, 1997), pluralistic thinking, and perception of racial climate (Hurtado & Ponjuan, 2005). These items, which are so important to understanding underrepresented students’ experiences in STEM higher education, have not been included in datasets that include majority students, such as BPS. Taking an assets-based approach to studying the experiences of underrepresented students will require broader datasets to integrate scales that have been shown to be particularly influential in Latinx and underrepresented students’ experiences, such as belonging, perceptions of unwelcoming climates, and pluralistic thinking. If they were included, this might increase awareness, access, and statistical power in ways that would lead to research that would prompt effective interventions to broaden participation of Latinx and Black students in STEM. Additionally, more work is needed for data sets and analyses to link specific questions about interactions with peers, staff, and intervention programs with outcomes such as sense of belonging (e.g., Hurtado & Carter, 1997; Hurtado & Ponjuan, 2005) and to link sense of belonging and acculturative stress to more traditional outcomes such as GPA (e.g., Chun et al., 2016) or persistence to graduation.

As shown in Table 2, just two studies, both qualitative, focused on Latinx STEM transfer students. We had to synthesize findings from often separate studies of 2-year, transfer, Latinx and STEM students to understand the factors that support academic success of Latinx students that matriculate at 2-year institutions and transfer to 4-year institutions to complete their STEM degrees. Studies that considered STEM majors as a variable or population are indicated in Tables 3, 4, and 5. Readers can see that these STEM studies are reasonably well-represented among the main categories of findings with a few notable exceptions. In Table 3, there are no STEM studies that explicitly referenced an assets-based framework in the analysis of their findings. Certainly, we can identify examples that use an assets-based perspective in studying STEM student success (e.g., Harper, 2010; Samuelson & Litzler, 2016; Wilson-Lopez et al., 2016); however, we did not find evidence that this perspective is being applied to Latinx STEM transfer students specifically. In Table 3, there are also no STEM-specific studies on outreach related to higher education. Outreach may well be important in STEM recruitment, but research we found has not focused specifically on outreach to support Latinx STEM students in 2-year institutions. In Table 4, there are no pedagogy/teaching studies on STEM students; most of these were focused broadly on Latinx students’ experiences with all instructors and were not conducted in a specific course. Our “Implications for Practice” section below expands on specific strategies that all instructors can follow to support Latinx students. Overall, however, we can conclude that many of the findings for non-STEM student populations are also relevant for STEM student populations. Additionally, there do not appear to be factors that are being investigated or found relevant only to STEM student populations.

Implications for practice

Table 4 summarizes our findings on how instructors influence the success of students that participated in the various studies, including Latinx students. Results in the table show positive instructor attitudes, approachability, accessibility, and encouragement contribute to constructive interactions with students while cultural disconnects between students and instructors can negatively affect student outcomes. Results in the table also show that instructional strategies that promote peer-to-peer interactions as well as culturally responsive teaching practices promote positive student outcomes. While constructive faculty-student interactions and instructional practices that support peer-to-peer interactions are well documented across multiple studies, our findings suggest that knowledge and understanding of culturally responsive teaching practices may be less widely known. Therefore, adopting a culturally relevant education framework, which we will present in this section, may act as a lever to improve both teaching practices as well as interactions between instructors and their students. We also examine how engaging in these assets-based pedagogies can shift instructors away from deficit mindsets and improve their interactions with students. Finally, we briefly discuss how institutions can support culturally relevant teaching practices as well as common misconceptions surrounding culturally relevant education.

Aronson and Laughter (2016) synthesized research from two seminal strands of literature, culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995) and culturally responsive teaching (Gay, 2010), to create a framework for culturally relevant education (CRE). Although both bodies of research are founded in social justice principles and seek to create social change through classrooms, the two strands emphasize slightly different foci. While Ladson-Billings’ work on culturally relevant pedagogy intends to influence instructors’ attitudes and perspectives that translate into every aspect of their teaching, Gloria Gay’s work on culturally responsive teaching focuses on teaching methods and practices instructors may use in their classrooms (Aronson & Laughter, 2016). The integrated, inclusive CRE framework synthesizes a broader range of related works (Aronson & Laughter, 2016; Dover, 2013).

Several reviews provide evidence that CRE practices benefit students in various ways. Aronson and Laughter (2016) have shown CRE practices have had direct, positive impact on student outcomes, specifically within STEM disciplines. They describe 13 studies that reported positive student outcomes in math and science courses implementing practices from the CRE framework. In another review of 45 classroom-based research studies, authors showed how explicit instructor actions, which could be related to CRE practices, benefitted students (Morrison et al., 2008). For example, Morrison et al. (2008) reported instructors using “student strengths as instructional starting points” and investing and taking “personal responsibility for students’ success” (p. 436). Both sets of instructor actions provide examples of CRE practices. A third review offers students’ perspectives of culturally relevant teaching. Byrd (2016) conducted a nationwide survey of 315 sixth through 12th grade students about their experiences with culturally relevant practices. Her findings showed CRE practices were significantly linked to both academic outcomes and racial identity development. In addition to supporting student outcomes, we propose that CRE practices promote positive interactions between instructors and their students by working against deficit-oriented perspectives.

The problem of deficit discourse framing diverse and low-income student populations in higher education is global. From the USA, to South Africa and Australia, researchers are working to problematize deficit thinking and move instructors and institutions away from viewing students and their families as the unit to be “fixed” (McKay & Devlin, 2016; O’Shea et al., 2016; Smit, 2012). Many well-intentioned instructors are aware of different cultures, while simultaneously holding deficit-oriented mindsets. These deficit mindsets may lead to lower expectations of students, reify deficit stereo types, and undermine reform efforts (Nelson & Guerra, 2014). Unfortunately, it can be difficult to shift deficit mindsets in individuals as these ideas are pervasive and often derived from larger beliefs about nondominant communities that permeate through society (García & Guerra, 2004; Valencia, 2010). Achieving this radical shift seems to necessitate sustained, systematic efforts organized around specific frameworks.

Evidence suggests that professional development promoting use of CRE practices has the potential to shift participants’ mindsets toward a more assets-based orientation and in turn, improve instructor-student interactions. For example, García and Guerra (2004) demonstrated that after completing development activities that created cognitive dissonance between ideas within culturally responsive pedagogy and previously held deficit beliefs, participants resolved those conflicts. Resolution prompted participants to examine and modify instructional practices in order to be more culturally responsive. Similarly, Warren (2018) argues for teaching perspective taking—“adopting the social perspectives of others as an act and process of knowing”—to instructors to help them develop CRE practices. Perspective taking increases instructors’ personal knowledge of students and the sociocultural context in which they are teaching. Acquiring personal knowledge of students and their communities can then work against assumptions on which deficit mindsets have been constructed. The knowledge gained from perspective taking supports instructors in how they respond to students within any given interaction. Instructors’ critical awareness and expectations of students have been shown to be directly related to their behavior within classrooms that can impact students’ ethnic and achievement identities (López, 2017). Thus, shifting instructors’ mindsets and increasing their critical awareness through professional development designed around CRE practices is critical for improving instructor-student interactions.

While the CRE framework supports initiatives to improve instruction and interactions with students, implementation of such initiatives requires thorough understanding and thoughtful consideration. Hurried applications of these frameworks may create misconceptions that can lead to misuse. Twenty years after the initial development of culturally relevant pedagogy, Ladson-Billings (2014) reflected on the evolution of the theory and its misuses. She cautioned against a shallow interpretation of culturally relevant pedagogy, one that sometimes results in well-intentioned instructors integrating course materials reflective of their students’ culture while ignoring critical aspects of the pedagogy. For example, instructors might choose a text that reflects common experiences of their students but fail to discuss or acknowledge policies that directly impact those students and their families (e.g., school choice, mass incarceration, school funding). To avoid such misinterpretations, we recommend that institutions both create teaching development programs on culturally relevant education and build infrastructure that supports their implementation. For example, the Center for Urban Education at the University of Southern California has developed self-assessment inventories to facilitate inquiry practices examining racial inequities within higher education. One of these self-assessment tools is based on the literature surrounding culturally relevant pedagogy; it guides instructors through a protocol to promote culturally inclusive practices (Dowd et al., 2012a, b).