Abstract

Background

A central aim in ecological research is to improve understanding of the interactions between species and their environments; these improvements will prove crucial in predicting the ecological consequences of climate change for isolated montane species, such as Royle's pika. We studied the influence of habitat microclimatic conditions on the activity patterns of Royle's pika in the period May to August (2008 to 2011) within six permanently marked plots deployed along an attitudinal gradient (2,900 to 3,680 m) within the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, India. Pika activity was recorded through direct observation during the period from 0600 to 1900 on each observation day and normalised as the percentage of individuals observed in an hourly interval relative to the maximum number of individuals sighted in a particular plot during the observation day. Microclimatic data in pika habitat were recorded across the altitudinal zones using automatic data loggers, a soil thermometer and a hygrometer deployed within the site during each observation interval.

Results

Using linear mixed effect models, we simulated pika activity as the number of active versus inactive individuals with logical alternate combinations of habitat microclimatic parameters, altitudinal zone and daily time interval. The pika had a bimodal activity pattern with high activity in the morning and evening hours and low activity during midday hours. The best fit candidate model demonstrated that pika activity increased with ambient humidity and decreased with increasing temperature.

Conclusions

The reduction of activity due to an increase in temperature was significantly higher in the subalpine zone (2,900 to 3,200 m) than in the alpine zone (3,400 to 3,680 m). Thus, Royle's pika avoids heat stress by reducing activity during warm midday hours and taking shelter in microclimatically favourable cooler talus habitat. We showed that changes in habitat microclimatic conditions (specifically, increases in temperature) might significantly restrict Royle's pika daytime activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Knowledge of the interactions between an organism and its environment is often considered crucial for improved understanding of species traits (Parmesan and Yohe [2003]). Species adapted to cold regions (high-altitude or high latitude) experience marked seasonality; the growing period for vegetation is short and winters are long (often with a thick snow cover). Thus, the occurrence and distribution of species in mountain ecosystems are strongly influenced by ambient temperature and precipitation (Grinnel [1917]; Heatwole and Taylor [1987]; Körner [2007]). Cold-adapted alpine species are more vulnerable to climate change than those in tropical or temperate environments. Furthermore, climate warming may occur more rapidly at high altitudes than at lower elevations (Naftz et al. [2002]; Mortiz et al. [2008]). Although the general trends are becoming clearer, the details of species-specific responses to climate change have not been documented for many alpine areas around the planet. Detailed quantitative baseline ecological studies are needed for improved understanding of direct and indirect effects of climate change on alpine species and for the design of effective conservation measures.

The distribution ranges of several species (including at least one high-altitude, small mammal) fluctuated both regionally and globally during the climate changes that occurred in previous glacial-interglacial periods. (Grayson [2006]; Mortiz et al. [2008]; Galbreath et al. [2009]; but also see Millar et al. [2013]). Walther et al. ([2002]) postulated that many montane species will migrate to higher altitudes if ambient temperatures increase during periods of climate change. However, some high-altitude lagomorphs, such as the talus-dwelling pikas (Ochotona spp.) are confined to small, isolated and fragmented pockets of the talus habitat throughout their lifespans and have limited capability for long-distance migration (Smith and Weston [1990]; Peacock [1997]). Moreover, pikas are already confined to high elevations and have little opportunity for dispersion to higher slopes. Rapid changes in climate during the latter part of the 20th century resulted in the local extinction of the American pika (Ochotona princeps), a high-altitude lagomorph, in many parts of the western USA (Beever et al. [2003], [2010], [2011], [2013]; Wilkening et al. [2011]). Pikas play an important ecological role in alpine-subalpine ecosystems (Lai and Smith [2003]). They serve as a prey base for several carnivores, such as marten, stoat, weasel, and red fox, especially during winter when other rodents hibernate (Roberts, [1977]; Aryal et al. [2010]). They also influence plant community composition in alpine meadows (Bagchi et al. [2006]; Smith and Foggin [1999]). Therefore, extirpation of pikas by climate change may have significant impacts on alpine ecosystems.

The relationship between climate and pika persistence is better documented in North America than in the Himalaya (MacArthur and Wang [1973], MacArthur and Wang [1974]; Smith [1974];Beever et al. [2003], [2010], [2011]; Wilkening et al. [2011]). Ray et al. ([2012]) showed that the persistence of American pikas is affected by microclimatic condition as well as by the availability of appropriate habitats at higher elevations, which may function as thermal refugia. Such studies of species-environment interactions contribute greatly to understanding of the impact of global climate change on specific ecosystems (Elith and Leathwick [2009]) because they aid in the prediction of species' responses to changes in temperature, precipitation, or other factors that alter their habitat conditions (Millar and Westfall [2010]; Beever et al. [2011]; Millar et al. [2013]). These predictions are especially useful when there are no baseline or historical data (which are essential for the detection of change) for a species that is highly vulnerable to climate shifts.

North American talus-dwelling pikas have a bimodal activity pattern (high activity during early morning and late evening) and take shelter in the cool, moist talus to avoid midday heat (MacArthur and Wang [1973], MacArthur and Wang [1974]; Smith [1974]; Beever et al. [2003], [2010], [2011]; Wilkening et al. [2011]). There is no equivalent information for any Himalayan pika species. Although seven species of pika occur in the Himalayas (Smith et al. [1990]), only a few short-term ecological studies (each a few weeks in duration) have been conducted (Kawamichi [1968], [1971]). An improved knowledge based on the relations between habitat microclimate and animal activity across different talus-dwelling pikas will contribute to better prediction of the possible impacts of climate change on the species.

We selected Royle's pika (Ochotona roylei Ogilby, 1839; 100 to 150 g of body mass; Alfred et al. [2006]) as a model species and explored the ways in which habitat microclimate influences the activity of these small alpine mammals. High animal detection probability, accessible habitats, simple movement patterns, high sensitivity towards climatic variation and sub-surface habitat usage make pikas excellent models for examining the influences of habitat microclimate on alpine mammals in general (MacArthur and Wang [1973], [1974]; Smith [1974]). Royle's pika inhabits open rocky ground and rock talus in Rhododendron forests at elevations from 2400 m through 5000 m in the Himalayan region extending from northwestern Pakistan through India, Nepal and the adjacent Tibetan plateau (Hoffmann and Smith [2005]; Chakraborty et al. [2005]). Unlike, North American species, Royle's pika does not have a prominent winter food hoarding behaviour (Kawamichi [1968]). Earlier studies have focused on the distribution pattern, winter behaviour, social organisation, abundance and foraging behaviour of Royle's pika (Kawamichi [1968], [1969], [1971]; Bhattacharyya et al. [2009]; Bhattacharyya et al. [2013]), but the influence of microclimatic conditions on the species’ behavioural responses has not yet been documented.

The major objective of this study was to describe the daily activity pattern of Royle's pika at different altitudes and then determine how habitat microclimate conditions affect these patterns. Other talus-dwelling pikas, such as American pikas, have behavioural thermoregulation to help cope with microclimatic variations, especially in temperature (Smith [1974]). Our postulates were as follows: i) the activity rate of Royle's pika is mainly influenced by habitat microclimate factors, such as ambient temperature and moisture and ii) the talus habitat is thermally favourable and provides appropriate temperature refuges for pikas. To test these postulates, we constructed a set of competing regression models in an information theoretic framework based on available ecological knowledge that incorporates diverse logical combinations of activity, ambient and inside-talus temperature, moisture, elevation and time of day.

Methods

Study area

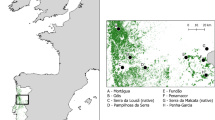

The study was performed in the Chopta-Tungnath sector (30°30′ to 31°29′N and 78°12′ to 79°13′E) of the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (ca. 975 km2) in Uttarakhand, India. The elevation in the study area ranges from 2,900 to 3,680 m (subalpine to alpine). The vegetation in the subalpine region comprised trees (Quercus semecarpifolia, Rhododendron arboreum, Abies pindrow, A. spectabilis and Sorbus sp) and shrubs (R. campanulatum), while diverse grasses (e.g. Danthonia cachemyriana, Carex setigera) and herbaceous plants (e.g. Trachydium roylei, Geum elatum, Plantago brachyphylla) dominated the alpine meadow vegetation (Sundriyal et al. [1987]). Pika habitats in the study area were rock talus and fractured boulder slope in the alpine meadows, forest edges and various anthropogenic constructs (Bhattacharyya et al. [2009]). Although the study area was located in the upper catchment of the Alaknanda River in the Chamoli District, Uttarakhand, India, it contained no glaciers or large streams. Hence, the rock taluses were highly fragmented and generally devoid of typical rock ice features (Millar and Westfall [2010]). The majority of pika habitats had medium to steep slopes and west or southwest aspects. Diverse carnivores, such as jackals (Canis aureus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), yellow-throated martens (Martes flavigula), Himalayan weasels (Mustela sibirica) and raptors such as Himalayan golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos daphanea) and common kestrels (Falco tinnunculus), were potential predators of pikas in the study area (Green [1985]; Aryal et al. [2010]). The local climate is influenced by southwest monsoons in the summer and westerly disturbances in the winter (Mani [1981]). There were five prominent seasons in the study area (Table 1; Adhikari et al. [2012]). The area received high precipitation (average annual precipitation: 2,410.5 ± 432.2 mm, mean ± SE) from the end of June until mid-September (Adhikari et al.[2012]).

Behavioural observations and microclimate data collection

This study was conducted during peak pika activity periods in 4 years (May to August 2008 and 2009; May to June 2010; June to July 2011). The study area was divided into three altitudinal zones based on vegetation: subalpine (2,900 to 3,200 m), timberline (3,200 to 3,400 m) and alpine (3,400 to 3,680 m). In each zone, we marked out two 50 × 50 m permanent plots in which we recorded the activity of Royle's pika and the microclimatic features of the habitat. Each permanent study plot was a little bigger than the pika home range size (27.5 × 40.5 m2, Kawamichi [1968]) and located a minimum distance of 100 m from any neighbouring plot; each plots had similar aspects and slopes. Pikas were scanned through 10 × 40 mm Nikon binoculars from a high vantage point from which the entire study plot was visible (Altmann [1974]). Individual animals were identified by size, moulting signs on the body and scar marks on their ears (Bhattacharyya et al. [2009]). Pika activity patterns were directly observed from 0600 to 1900 in each day and analysed on an hourly interval basis, giving a total of 13 h of observations per session per plot. The proportion of active individuals (hereafter, ‘activity’) was indexed as percentage of individuals observed in one interval (1 h) relative to the maximum number of individuals sighted on that particular day in a given plot.

The habitat microclimate parameters recorded during this study were inside-talus temperature and humidity, open-area surface temperature and humidity and ambient temperature. Pikas live within the talus slopes or slide rocks in natural crevices formed between the rocks. Atmospheric temperature was recorded with automatic HOBO™ data loggers (Onset Computer Inc., Bourne, MA, USA) every 10 min. The loggers were placed in secure locations (e.g. tree hollows) at 2 m high and away from direct sunlight. Temperature data were downloaded and averaged to yield hourly average values. Inside-talus temperature and humidity were recorded every 30 min with a soil thermometer (Reotemp Inst. Crop. San Diego, CA, USA) and a hygrometer (Huger, Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany), respectively; the devices were inserted about 80 to 100 cm into the crevices during each observation interval, and values were averaged to obtain hourly values. Open-ground surface temperature and humidity were measured similarly at a random location within the site.

Data analysis

We used a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test to detect significant differences in activity rate during different time intervals. The multicolinearity between different microclimatic variables (ambient temperature, open-area surface temperature, inside-talus temperature, inside-talus humidity and ambient humidity) was examined through Pearson's correlation analysis using SPSS 16 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Temperature- and humidity-related variables were correlated (r > 0.4). Therefore, generalised linear regression was used to model activity as a function of predictor variables (temperature-related: ambient temperature, inside-talus temperature, open-area surface temperature; humidity-related: ambient humidity, inside-talus humidity) in an information-theoretic (I-T) framework. Relative support for each model and each predictor was compared (Akaike information criterion (AIC), Burnham and Anderson [2002]) and the most important temperature- and humidity-related variables (ambient temperature and humidity, see the ‘Results’ section below) were used in further analyses to predict their relationships with pika activity. Diurnal ambient temperature and humidity might be influenced by altitudinal zone as well as by time of day; therefore, ambient temperature was first regressed against altitudinal zone, and the unstandardised residuals were saved. These un-standardised residuals were regressed against time of day to obtain residuals of ambient temperature that were influenced by altitudinal zone or time. The same procedure was followed for ambient humidity. Correlated variables were not included in the same candidate model other than as specified interaction terms.

Pika activity was modelled as the number of individuals that were active versus those that were inactive, with logical alternate combinations of ambient temperature, ambient humidity residual values, altitudinal zone and time group. Although pika observations were separated by different sites and time interval to ensure independence of observations, the nesting of pika observations within sites might have been interdependent, thereby violating assumptions relating to independence of the regression technique (Zar [1999]). To eliminate this problem, generalised linear mixed-effect models (logit link and binomial errors) were used with different sites as random intercepts and years as slopes. This method helps identify the natural grouping of observations and also explicitly account for random variations in the odds of activity between sites and years that might arise from intra-site or year correlations, while other factors remained constant (Zuur et al. [2009]). Following Zuur et al. ([2009]), candidate models were designed by Laplace approximation and maximum likelihood parameter estimation using the ‘lmer’ function of the ‘lme4’ package in R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org/).

Each candidate model was formulated on the basis of one or more predictor variables. We predicted that the pika activity rate i) would be influenced by additive as well as interactive effects of ambient temperature and humidity and ii) depends on interactive as well as additive effects of altitudinal zone, time of day, ambient temperature and humidity. In total, seven models for pika activity and microclimate were compared for support of various hypotheses including a null (intercept-only) model. An information theoretic approach (AIC) was used to select the best fit model (lowest AIC), and we obtained final parameter estimates by the restricted maximum likelihood method. We used paired t tests to determine whether the microclimate conditions (temperature and humidity) within the talus habitat were significantly different from the outside environment during midday hours. This would help determine whether or not the talus acts as a thermal refuge for pikas.

Results

In the subalpine zone, the pika habitat included forest gaps with large rocks (at 2,900 m) and rock talus (at 3,150 m) with large and medium-sized rocks. A pika habitat in the timberline zone was found in rock talus (at 3,280 m) with rolling boulders and embedded rocks interspersed with mixed herbaceous meadows (at 3,300 m). The pika habitat in the alpine zone was mostly confined to areas with medium-sized rocks in the rock talus (at 3,444 m) and anthropogenic constructs such as stone walls, historic foundations and rockwork dams (at 3,520 m). The maximum number of individuals detected during an observation interval at any site across all visits in a year ranged from 0 to 7; thus, our assumption that the maximum number of individuals observed during each session may be considered as a reasonable surrogate of population size in a particular plot was supported.

Pikas had a bimodal activity pattern during 936 h of observations in different altitudinal zones (Figure 1). Our post hoc ANOVA test detected three groups of activity: morning, day and evening (Table 2). Maximum activity was observed in early morning and during the evening, while activity dipped to its lowest level in midday hours. The year 2009 was the warmest and driest over the whole study period. During May to June 2009, pika activity completely ceased from 1200 to 1400 in the alpine zone and from 1100 to 1400 in the subalpine zone. In the timberline zone, activity was reduced in the midday hours but did not stop altogether in 2008, 2010 or 2011. Pika activity was highest in the timberline zone during morning (73.73% ± 2.61%, mean ± SE) and evening (80.00% ± 2.46%); in the alpine zone, activity was highest (34.98% ± 2.04%) during the day. Low pika activity was recorded in the subalpine zone in all time periods, with lowest values around midday (19.22% ± 1.69%). No significant seasonal variation (Mann-Whitney U test: W = 10, p = 0.68) was observed in pika activity during midday hours (1100 to 1600).

Measurements of microclimatic conditions indicate that the talus habitat was generally cooler and moister than the outer environment (Figure 2). During the warm midday hours when the outside environment was hot and dry, the talus habitat was significantly cooler (inside-talus temperature: 10.0°C ± 0.01°C; ambient temperature: 12.40°C ± 0.14°C; paired t test: t = −18.22; df = 359; p < 0.001) and moister (inside-talus humidity: 62.62% ± 0.08%; ambient humidity: 60.43% ± 0.96%; paired t test: t = 3.11; df = 359; p < 0.01). But in the early morning (0600 to 0800) and late evening (1800 to 1900), talus values were significantly warmer (early morning hours inside the talus: 8.59°C ± 0.25°C; ambient: 7.32°C ± 0.27°C; paired t test: t = 12.12; df = 143; p < 0.001; late evening hours inside the talus: 9.66°C ± 0.20°C; ambient: 8.40°C ± 0.21°C; paired t test: t = 9.39; df = 73; p < 0.001) than the outside environment.

Royle's pika habitat microclimatic parameters. The parameters (ambient temperature is shown by a black solid line, inside-talus temperature is shown by black dashed lines, ambient humidity is shown by a grey line) in different altitudinal zones (a, b, c) and time intervals throughout the entire study period (2008 to 2011).

Ambient temperature and humidity, other temperature-related variables (inside-talus temperature and open-area surface temperature) and humidity-related variables (inside-talus humidity) received more support (∆AIC >2) than the null model as explanatory predictors of any relationship between pika activity and microclimate. Therefore, ambient temperature and humidity were used in further analyses of the way in which pika activity was governed by direct and interactive influences of habitat microclimatic conditions, altitude and time of day.

The best candidate model explaining the relationship between pika activity and habitat microclimate received more support than the null model (∆AIC = 1,263.83), and no other model received similar support (all ∆AIC values >2, Table 3). The standard deviation of site random effects was negligible (SD = 10−13), but the year standard deviation across sites was large (Year 2009, SD = 0.034; Year 2010, SD = 0.052; Year 2011, SD = 0.076) indicating that much of the variability in activity was random variation between site-year combinations. In the best fit model, a proportion of pika activity was found to be explained by the additive effects of ambient humidity, time of day and the interactive effects of ambient air temperature and altitudinal zone. The best fit model β-coefficient estimates suggested a negative influence of ambient temperature (β = −0.14 ± 0.01, p < 0.001) and a positive influence of ambient humidity (β = 0.01 ± 0.001, p < 0.001) on pika activity (Table 4). The model also suggested that pika activity was significantly lower in the subalpine zone (β = −0.43 ± 0.08, p < 0.001) compared to that in the alpine zone. Pika activity was significantly lower (β = −1.48 ± 0.074, p < 0.001) during daytime hours than in the early morning or evening hours. The interactive effect of ambient temperature and altitudinal zone suggests that when ambient temperature increases, pika activity will significantly reduce (β = −0.06 ± 0.02, p < 0.05) more in the subalpine zone than in the alpine or timberline zones. The random effect of the best fit candidate model indicated a very low site effect.

Discussion

Activity is considered to be the most significant factor contributing to variability in physiological states (especially body temperature) among small mammals (McNab and Morrison [1963]; Hart [1971]). Pika populations generally avoid midday heat during summer. The American pika (O. princeps) becomes inactive during the early daytime hours at low altitude but remains active throughout the day at high altitude (Hall [1946]; Smith [1974]). The Collared pika (O. collaris) remains active throughout the day in Canada, whereas the Japanese pika (O. hyperborea) is active during early morning and late evening for parts of the year other than monsoonal periods, when it remains active throughout the day (Broadbooks [1965]; Kawamichi [1969]). In winter, the large-eared pika (Ochotona macrotis) remains active all day, presumably because it lives at higher altitudes than Royle's pika in Nepal (O. roylei), which remains active only during dawn and dusk hours in winter (Kawamichi [1971]). Similarly, Alpine pika (Ochotona alpina), Northern or Siberian pika (Ochotona hyperborea) and Turkestan red pika (Ochotona rutila) are also diurnal, but Ili pika in China is reported to have a nocturnal activity pattern (Kawamichi [1969]; Smith et al. [1990]; Sokolov et al. [2009]).

Royle's pika tended to avoid the daytime warm temperatures by restricting high levels of activity to early morning and late evening. Activity increased with increasing altitude. The data support the hypothesis that Royle's pika, like other talus-dwelling pikas (O. princeps), has behavioural thermoregulation in addition to physiological mechanisms of temperature control. When stressed by high temperatures, the animals at low altitudes seem to restrict their diurnal activity (Smith [1974]). Results of our best fit regression model which fits our first prediction, temperature and humidity, are key controlling elements in pika behaviour. We found that the impact of habitat microclimate on pika activity was strongest at low altitude. Royle's pika lives in very deep crevices in rock talus, and due to logistical constrains, we were able to record the temperature and humidity only at 80 to 100 cm inside the talus. Hence, the temperature and humidity difference between the talus inside and outside environments (approximately 2%) reported may be comparatively lower than what pikas might experience in reality further deep inside the talus.

Pikas spend 25% to 55% of their surface active time foraging (Smith and Ivins [1983]). Pikas were less active (<40% of animals active) in the subalpine zone (than in the alpine zone) for longer periods of time (5 h of inactivity in the subalpine zone versus 2 h in the alpine). Differences in ambient temperatures between the zones accounted for these differences in activity patterns. Royle's pika does not hoard a winter hay pile (Kawamichi [1968]); after a long winter with very limited food availability, the summer-monsoon season is the only period of the year in which adequate energy reserves can be accumulated through the consumption of food. However, daytime high temperatures reduce pika activity, and hence food intake, during some of the daylight hours. High midday temperatures may impose crepuscular foraging on the animals, which in turn might lead to increased predation risk. These trends have been observed in other temperature-sensitive species, such as Mexican lizards, which face high local extinction risk due to temperature-induced activity restriction during the reproductive season (Sinervo et al. [2010]). These activity restrictions prevent the acquisition of adequate resources through foraging, and the impact on resources required for reproduction has negative effects on the population growth rate.

Diverse physiological constraints may be important determinants of the distributional limits of species and populations (Gaston and Spicer [1998]; Chown and Gaston [2000]). Generally, pikas have a higher (2°C to 3°C higher) body temperature than other small mammals living in talus areas. The elevated body temperatures of pikas are attributable to their thick fur layer and to the presence of microorganisms such as bacteria, which aid in digestion (MacArthur and Wang [1973]). Early studies on the behaviour and physiology of the American pika, which has ecological requirements similar to those of Royle's pika, demonstrated that the animals become hyperthermic and die after even a brief exposure to moderate ambient temperatures (25.5°C to 29.4°C) and intense solar radiation, a combination that prevented thermoregulation (MacArthur and Wang [1973], [1974]; Smith [1974]). American pikas have a relatively narrow differential between their resting (40.1°C) and lethal (43.1°C) body temperatures, which is a reflection of a limited capability for handling heat stress (MacArthur and Wang [1973]). Grinnel ([1917]) suggested that temperature is a key factor that governs American pika distribution. Temperature is also among the primary environmental factors controlling juvenile pika dispersal (Smith [1974]; Hafner [1994]) and is a plausible predictor in many American pika extirpation and distribution change models (Wilkening et al. [2011]). A winter snow cover provides thermal insulation for pikas exposed to extreme temperature fluctuations; an adequate snow cover reduces cold stress and increases survival (Marchand [1996]; Franken and Hik [2004]; Morrison and Hik [2007]; Beever et al. [2010]). The American pika uses talus for thermoregulation because the habitats it provides are cool, moist refuges in the summer months and provide insulation from cold in the winter (Beever et al. [2010]). Our measurements of Royle's pika talus habitat microclimatic conditions support our prediction that talus provides a thermal refuge: the talus microclimate was significantly cooler and more stable than the outer environment, especially during midday hours. Pikas reduced their surface activity and remained in their talus habitat during the warmest time of the day, thereby avoiding heat stress. Similar to pikas, other montane small mammals such as yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota marmota) were also found to avoid midday high temperature and take refuge inside their cooler burrows (Türk and Arnold [1988]). They were found to reduce above-ground activities and take short foraging bouts when ambient temperature exceeds 25°C (Türk and Arnold [1988]). Piute ground squirrels (Spermophilus mollis) were also found to be active throughout the day in cooler microclimate at the sagebrush habitat and showed restricted bimodal activity in warm grassland habitat (Sharpe and Horne [1999]). White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) activity was found to be high when ambient temperature ranges between 6°C to 16°C and further fluctuations in ambient temperature reported to decrease their activity rate significantly (Beier and McCullough [1990]). High environmental temperature were also found to decrease foraging activity, increase grooming and resting activity in primates such as chacma baboons (Papio hamadryas ursinus; Hill [2006]). Furthermore, behavioural thermoregulation was also found to affect their habitat choice and day journey routes (Hill [2006]).

Earlier research demonstrated a significant influence of the unique characteristics of talus habitats and of climatic drivers on American pika populations (Ray et al. [2012]; Jeffress et al. [2013]). Millar and Westfall ([2010]) found that periglacial rock ice features in pika habitat creates unique microclimatic conditions that make these rock taluses significantly cooler in summer and warmer in winter, creating a desirable thermal refuge. Beever et al. ([2008]), Simpson ([2009]); Rodhouse et al. ([2010]) and Millar et al. ([2013]) recently reported the existence of low-elevation pika populations that persist beyond the limits of their previously described bioclimatic niche. Erb et al. ([2011]) determined that of 69 locations historically occupied by pikas in the southern Rocky Mountains (USA), only four have been extirpated over recent decades. Moreover, Jeffress et al. ([2013]) found that the relationship between climate and American pika distributions was complex and locality-specific, suggesting multiple mechanisms through which climate may affect the focal species. Thus pika responses towards climate change are not simple and can vary significantly among locations. However, with the exception of North American pikas, information on the influence of habitat microclimate, thermal biology and the potential impact of climate change on population ecology is extremely limited for these small mammals (Table 5). Our study provides new data on the thermal biology of an Asian, talus-dwelling pika that occurs at relatively low latitudes and experiences climatic conditions (e.g. warmer summer and high monsoon precipitation) different from those of American pikas. We provide critical baseline ecological information for future climate change research on small mammals in the Himalaya. This is only a first step, for the mechanisms through which climate stress acts need to be studied comprehensively in order to better understand how climate change affects biotas and to enable a wider application of information for monitoring, management and conservation strategies (Hallett et al. [2004]; Ray et al. [2012]).

Conclusions

An understanding of factors influencing Royle's pika activity is fundamental for evaluating the long-term viability of the species in the Himalaya. The alpine region of the Himalayas is extremely vulnerable to global warming (Singh and Bengtsson [2004]). During the last two decades, seasonal mean temperatures in western Himalaya have increased by approximately 2°C and maximum temperatures have increased by approximately 2.8°C (Shekhar et al. [2010]). If climate at lower altitudes were to become inhospitable for Royle's pikas because of changes in temperature, the animals are likely to move upslope, like other alpine mammalian species (Guralnick [2007]). Though this upslope range shift might help them cope with the warming climate, it may not improve connectivity between habitats, which in the long run will reduce the resilience of pika populations in the face of any threat, including climate change (Gilpin and Soulé [1986]; Sekercioglu et al. [2008]) and may finally lead to local extinction of the species. Alternatively, as we demonstrated in this study, Royle's pikas might also be able to cope and survive in changing environments through behavioural adaptation to avoid heat stress, i.e. occupying thermal refuges (habitat with cool and moist microclimate).

Authors’ information

SB is currently a postdoctoral research associate at Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, member of IUCN/SSC lagomorphs specialist group and formerly senior research fellow of the Wildlife Institute of India. BSA is Scientist-F at the Department of Habitat Ecology in Wildlife Institute of India and GSR is Scientist-G at the Department of Habitat Ecology in Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.

References

Adhikari BS, Rawat GS, Bhattacharyya S, Rai ID, Bharati RR: Ecological assessment of timberline ecotone in Western Himalaya with special reference to climate change and anthropogenic pressures. Final Report. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India; 2012.

Alfred JRB, Das AK, Sanyal AK: Animals of India: mammals. Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata, India; 2006.

Altmann J: Observational study of behaviour: sampling methods. Behaviour 1974, 69: 227–263. 10.1163/156853974X00534

Aryal A, Sathyakumar S, Kreigenhofer B: Opportunistic animal’s diet depend on prey availability: spring dietary composition of the red fox ( Vulpes vulpes ) in the Dhorpatan hunting reserve, Nepal. J Ecotoxicol Environ Monit 2010, 2: 59–63.

Bagchi S, Namgail T, Ritchie ME: Small mammalian herbivores as mediators of plant community dynamics in the high-altitude arid rangelands of Trans-Himalaya. Biol Conserve 2006, 127: 438–442. 10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.003

Beever EA, Brussard PF, Berger J: Patterns of apparent extirpation among isolated populations of pikas ( Ochotona princeps ) in the Great Basin. J Mammal 2003, 84: 37–54. 10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0037:POAEAI>2.0.CO;2

Beever EA, Wilkening JL, Mcivor DE, Weber SS, Brussard PE: American pikas ( Ochotona princeps ) in north western Nevada: a newly discovered population at a low-elevation site. West N Am Nat 2008, 68: 8–14. 10.3398/1527-0904(2008)68[8:APOPIN]2.0.CO;2

Beever EA, Ray C, Mote PW, Wilkening JL: Testing alternative models of climate mediated extirpations. Ecol Appl 2010, 20: 164–178. 10.1890/08-1011.1

Beever EA, Ray C, Wilkening JL, Brussard PE, Mote PW: Contemporary climate change alters the pace and drivers of extinction. Global Change Biol 2011, 17: 2054–2070. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02389.x

Beever EA, Dobrowski SZ, Long J, Mynsberge AR, Piekielek NB: Understanding relationships among abundance, extirpation, and climate at eco regional scales. Ecology 2013, 94: 1563–1571. 10.1890/12-2174.1

Beier P, McCullough DR: Factors influencing white-tailed deer activity patterns and habitat use. Wildlife Monogr 1990, 190: 3–51.

Bhattacharyya S, Adhikari BS, Rawat GS: Abundance of Royle's pika ( Ochotona roylei ) along an altitudinal gradient in Uttarakhand, Western Himalaya. Ital J Mammal 2009, 20: 111–119.

Bhattacharyya S, Adhikari BS, Rawat GS: Forage selection by Royle's pika ( Ochotona roylei ) in the western Himalaya, India. Zoology 2013, 116: 300–306. 10.1016/j.zool.2013.05.003

Broadbooks HE: Ecology and distribution of pikas of Washington and Alaska. Am Midl Nat 1965, 73: 299–335. 10.2307/2423457

Burnham KP, Anderson DR: Model selection and multimodal inference. Springer-Verlag, New York; 2002.

Chakraborty S, Bhattacharyya TP, Srinvasulu C, Venkataraman M, Goonatilake WLDPTS De A, Sechrest W, Daniel BA (2005) Ochotona roylei (Ogilby, 1839). In: Molur S, Srinivasulu C, Srinivasulu B, Walker S, Nameer PO, Ravikumar L (ed) Status of South Asian Non-volant Small Mammals: Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (C.A.M.P.). Workshop Report, Coimbatore, India

Chown SL, Gaston KL: Areas, cradles and museums: the latitudinal gradient in species richness. Trends Ecol Evol 2000, 8: 310–315.

COSEWIC (2011) COSEWIC assessment and status report on the collared pika Ochotona collaris in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, p 50

Elith J, Leathwick J: Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annu. Rev Ecol Syst 2009, 40: 677–697. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159

Erb LP, Ray C, Guralnick R: On the generality of a climate-mediated shift in the distribution of the American pika ( Ochotona princeps ). Ecology 2011, 92: 1730–1735. 10.1890/11-0175.1

Franken RJ, Hik DS: Influence of habitat quality, patch size and connectivity on colonization and extinction dynamics of collared pikas ( Ochotona collaris ). J Anim Ecol 2004, 73: 889–896. 10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00865.x

Galbreath KE, Hafner DJ, Zamudio KR: When cold is better: climate-driven elevation shifts yield complex patterns of diversification and demography in an alpine specialist (American pika, Ochotona princeps). Evolution 2009, 63: 2848–2863. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00803.x

Gaston KJ, Spicer JL: Do upper thermal tolerances differ in geographically separated populations of the beach flea Orchestia gammarellus (Crustacea: Amphipoda). J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 1998, 229: 265–276. 10.1016/S0022-0981(98)00057-4

Gilpin ME, Soulé ME: Minimum viable populations: the processes of species extinctions. In Conservation biology: The science of scarcity and diversity. Edited by: Soulé M. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA; 1986:13–24.

Grayson DK: The late quaternary biogeographic histories of some Great Basin mammals (western USA). Quat Sci Rev 2006, 25: 2964–2991. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.03.004

Green MJB: Aspects of the ecology of the Himalayan musk deer. Ph.D. dissertation, Cambridge University, UK; 1985.

Grinnel J: Field tests of theories concerning distributional control. Am Nat 1917, 51: 115–128. 10.1086/279591

Guralnick RP: Differential effects of past climate warming on mountain and flat land species‘ distributions: a multispecies North American mammal assessment. Global Ecol Biogeogr 2007, 16: 14–23. 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00260.x

Hafner DJ: Pikas and permafrost: post-Wisconsin historical zoogeography of Ochotona in the Southern Rocky Mountains, USA. Arct Antarc Alp Res 1994, 26: 375–382. 10.2307/1551799

Hall ER: Mammals of Nevada. University of California Press, Berkeley; 1946.

Hallett TB, Coulson T, Pilkington JG, Clutton-Brock TH, Pemberton JM, Grenfell BT: Why large-scale climate indices seem to predict ecological processes better than local weather. Nature 2004, 430: 71–75. 10.1038/nature02708

Hart JS: Rodents. In Comparative Physiology of Thermoregulation. Edited by: Whittow GC. II. Mammals. Academic Press, New York; 1971:2–130.

Heatwole H, Taylor J: Ecology of reptiles. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping Norton, New South Wales; 1987.

Hill RA: Thermal constraints on activity scheduling and habitat choice in baboons. Am J Phys Anthropl 2006, 129: 242–249. 10.1002/ajpa.20264

Hoffmann RS, Smith AT: Lagomorphs. In Mammal Species of the World. 3rd edition. Edited by: Wilson DE, Reeder DM. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland; 2005:185–211.

Irving L, Krog J: Body temperatures of arctic and subarctic birds and mammals. J Appl Physiol 1954, 6: 667–680.

Jeffress MR, Rodhouse TJ, Ray C, Wolff S, Epps CW: The idiosyncrasies of place: geographic variation in the climate-distribution relationships of the American pika. Ecol Appl 2013, 23: 864–878. 10.1890/12-0979.1

Kawamichi T: Winter behaviour of the Himalayan pika, ochotona roylei . Journal of faculty of science, Hokkaido university. VI Zool 1968, 16: 582–594.

Kawamichi T: Behaviour and daily activities of Japanese pika, Ochotona hyperborea yseoensis . Journal of faculty of science, Hokkaido University Ser. VI Zool 1969, 17: 127–151.

Kawamichi T: Daily activities and social pattern of two Himalayan pikas, Ochotona macrotis and O. roylei , observed at Mt. Everest. Journal of faculty of science, Hokkaido University Ser. VI Zool 1971, 17: 587–609.

Kawamichi T: Behavior and social organization of five species of pikas and their evolution. In Contemporary mammalogy in China and Japan. Edited by: Kawamichi T. Mammal Soci, Japan; 1985:43–50.

Körner C: The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends Ecol Evol 2007, 22: 569–574. 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.006

Lai CH, Smith AT: Keystone status of plateau pikas ( Ochotona curzoniae ): effect of control on biodiversity of native birds. Biodiv Conserv 2003, 12: 1901–1912. 10.1023/A:1024161409110

Li W, Li H, Hamit X, Ma J, Zhao W: Preliminary research on the daily activity rhythm of the Ili pika. Arid Zone Res 1993, 1: 54–57. [in Chinese]

MacArthur A, Wang LCH: Physiology of thermoregulation in the pika, Ochotona princeps . Can J Zool 1973, 51: 11–16. 10.1139/z73-002

MacArthur A, Wang LCH: Behavioural thermoregulation in the pika Ochotona princeps: a field study using radio telemetry. Can J Zool 1974, 52: 353–358. 10.1139/z74-042

MacDonald SO, Jones C: Ochotona collaris . Mamm Species 1987, 281: 1–4. 10.2307/3503971

Mani A: The climate of Himalaya. In The Himalaya. Edited by: Lall JS. Aspects of Change Oxford University Press, New Delhi; 1981:3–15.

Marchand PJ: The changing snowpack. In Life in the Cold. 3rd edition. University Press of New England, Hanover; 1996:11–39.

McNab BK, Morrison P: Body temperature and metabolism in subspecies of Peromyscus from arid and mesic environments. Ecol Monogr 1963, 33: 63–82. 10.2307/1948477

Millar CI, WestfalL RD: Distribution and climatic relationships of the American pika ( Ochotona princeps ) in the Sierra Nevada and western Great Basin, U.S.A.: periglacial landforms as refugia in warming climates. Arct Antarc Alp Res 2010, 42: 76–88. 10.1657/1938-4246-42.1.76

Millar CI, Westfall RD, Delany DL: New records of marginal locations for American pika ( Ochotona princeps ) in the western Great Basin. West N Am Nat 2013, 73: 457–476. 10.3398/064.073.0412

Morrison FS, Hik DS: Demographic analysis of a declining pika Ochotona collaris population: linking survival to broad-scale climate patterns via spring snowmelt patterns. J Anim Ecol 2007, 76: 899–907. 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01276.x

Mortiz C, Patton JL, Conroy CJ, Parra JL, White GC, Beissinger SR: Impact of a century of climate change on small-mammal communities in Yosemite national park, USA. Science 2008, 322: 261–264. 10.1126/science.1163428

Naftz DL, Susong DD, Schuster PF, Cecil LD, Dettinger MD, Michel RL, Kendall C: Ice core evidence of rapid air temperature increases since 1960 in alpine areas of the Wind River Range, Wyoming, United States. J Geophys Res 2002, 107: 10–29.

Parmesan C, Yohe G: A globally coherent fingerprint of climate changeimpacts across natural systems. Nature 2003, 421: 37–42. 10.1038/nature01286

Peacock MM: Determining natal dispersal patterns in a population of North American pikas ( Ochotona princeps ) using direct mark-resight and indirect genetic methods. Behav Ecol 1997, 8: 340–350. 10.1093/beheco/8.3.340

Ray C, Beever E, Loarie S: Retreat of the American pika: up the mountain or into the void? In Conserving Wildlife Populations in a Changing Climate. Edited by: Brodie JF, Post E, Doak D. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL; 2012:245–270.

Roberts TJ: The mammals of Pakistan. Ernest Benn Ltd, London; 1977.

Rodhouse TJ, Beever EA, Garrett LK, Irvine KM, Jeffress MR, Munts M, Ray C: Distribution of American pikas in a low-elevation lava landscape: conservation implications from the range periphery. J Mammal 2010, 91: 1287–1299. 10.1644/09-MAMM-A-334.1

Sekercioglu CH, Schneider SH, Fay JP, Loarie SR: Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions. Conserv Biol 2008, 22: 140–150. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00852.x

Sharpe PB, Horne VB: Relationships between the thermal environment and activity of Piute ground squirrels (Spermophilus mollis). J Therm Biol 1999, 24: 265–278. 10.1016/S0306-4565(99)00021-2

Shekhar S, Chad H, Kumar K, Srinivasan K, Ganju A: Climate-change studies in the western Himalaya. Ann Glaciol 2010, 51: 105–112. 10.3189/172756410791386508

Simpson WG: American pikas inhabit low-elevation sites outside the species' previously described bioclimatic envelope. West N Am Nat 2009, 69: 243–250. 10.3398/064.069.0213

Sinervo B, Mendez-De-La-Cruz F, Miles DB, Heulin B, Bastiaans E, Villagrán-Santa Cruz M, Sites JW: Erosion of lizard diversity by climate change and altered thermal niches. Science 2010, 328: 894–899. 10.1126/science.1184695

Singh P, Bengtsson L: Hydrological sensitivity of a large Himalayan basin to climate change. Hydrol Process 2004, 18: 2363–2385. 10.1002/hyp.1468

Smith AT: The distribution and dispersal of pikas: influences of behaviour and climate. Ecology 1974, 55: 368–376.

Smith AT, Foggin JM: The plateau pika ( Ochotona curzoniae ) is a keystone species for biodiversity on the Tibetan plateau. Anim Conserv 1999, 2: 235–240. 10.1111/j.1469-1795.1999.tb00069.x

Smith AT, Ivins BL: Colonization in a pika population: dispersal vs. philopatry. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 1983, 13: 37–47. 10.1007/BF00295074

Smith AT, Weston ML: Ochotona princeps. Mamm Species 1990, 352: 1–8. 10.2307/3504319

Smith AT, Formozov NA, Hoffmann RS, Changlin Z, Erbajeva MA: The pikas. In Rabbits, Hares and Pikas: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Edited by: Chapman JA, Flux JC. The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland; 1990:14–60.

Sokolov VE, Ivanitskaya EY, Gruzdev VV, Heptner VG: Lagomorphs: mammals of Russia and adjacent regions. Science Publishers, New Hampshire; 2009.

Sundriyal RC, Joshi AP, Dhasmana R: Phenology of high altitude plants at Tungnath in Central Himalaya. Trop Ecol 1987, 28: 289–299.

Türk A, Arnold W: Thermoregulation as a limit to habitat use in alpine marmots ( Marmota marmota ). Oecologia 1988, 76: 544–548.

Walther GR, Post E, Convey P, Menzel A, Parmesan C, Beebee TJC, Fromentin JM, Guldberg OH, Bairlein F: Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 2002, 416: 389–395. 10.1038/416389a

Wilkening JL, Ray C, Beever EA, Brussard PF: Modelling contemporary range retraction in Great Basin pikas ( Ochotona princeps ) using data on microclimate and microhabitat. Quatern Int 2011, 235: 77–88. 10.1016/j.quaint.2010.05.004

Zar JH: Biostatistical analysis. 4th edition. Prentice Hall, New Jersey; 1999.

Zuur AF, Leno EN, Walker N, Saveliev AA, Smith GM: Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer, New York; 2009.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Director and Dean of the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) for providing the funds, necessary facilities and support for smooth execution of this project and to Uttarakhand State Forest Department for permission to do the field work. Thanks are also due to Mr. Pankaj Singh Bisth, Mr. Gabbar Singh Bisth, who helped in the field work, and Mr. Sutirtha Dutta, Dr. Chris Ray for helping in data analysis, A.A. Lissovsky for helping to obtain information from pika literatures published in Russian language and Alex Arreola, Prof. A. Chapman (AuthorAids mentors) for helping in manuscript editing. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments to the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SB, BSA and GSR actively participated in study design. SB did the data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhattacharyya, S., Adhikari, B.S. & Rawat, G.S. Influence of microclimate on the activity of Royle's pika in the western Himalaya, India. Zool. Stud. 53, 73 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40555-014-0073-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40555-014-0073-8