Abstract

The suitability of Hansen solubility parameters as descriptors for modelling analyte retention during reversed-phase chromatographic experiments was investigated. A novel theoretical model using Hansen solubility parameters as the basis for a complete mathematical derivation of the model was developed. The theoretical model also includes the cavitation volumes of the analytes, which were calculated using ab initio density functional theory methods. A set of three homologous phthalates was used for experimental data collection and subsequent model construction. The training error and the generalization error of the model were additionally evaluated using a range of chemically diverse analytes. Statistical evaluation of the results revealed that the model is suitable for analyte retention prediction but is limited to the analytes used in the model construction. Therefore, the resulting theoretical model cannot be easily generalized. A retention anomaly attributed to the column temperature and mobile phase composition was experimentally observed and mathematically investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Considerable research interest has been devoted to understanding the principal mechanism of reversed-phase (RP) chromatographic separations, which has not been fully elucidated due to its complexity and a multitude of parameters that greatly affect the chromatographic experiment (Poole 2019). Poole (2015) described a qualitative interphase model which aimed at simplifying the complexity of the retention mechanism. He described the active chromatographic separatory area inside the analytical column and segmented it into three main domains: the silica particle surface, the stationary phase (SP), and the bulk mobile phase (MP). At a constant composition of the MP, the SP becomes solvated. Analytes approaching from the bulk MP can interact with the SP in a combination of two retention mechanisms: a partition and an adsorption mechanism (Poole 2019, 2015). The predominant mechanism, by which retention of the analyte occurs, is a function of MP composition, column temperature, condition and age of the SP, and the flow rate (Vailaya 2005). From a modelling perspective, this complexity presents the greatest challenge, as certain simplifications are unavoidable.

Retention prediction and modelling in chromatography

Haddad et al. (2021) recently published an overview of modern approaches to modelling chromatographic retention data. They can be divided into two main classes: statistical and physicochemical modelling. Statistical approaches include quantitative structure-retention relationships (QSRR) (Amos et al. 2018) and design of experiments (DoE) (Sahu et al. 2018), while, physicochemical models encompass solvatophobic models (Horváth et al. 1976; Moldoveanu and David 2015), solvent strength models (Neue and Kuss 2010; Tyteca and Desmet 2015), and linear free-energy relationships (LFER) (Vailaya 2005), which can be further divided into exothermodynamic relations (Ovčačíková et al. 2016), hydrophobic subtraction models (Snyder et al. 2004) and solvation parameter models (Abraham et al. 2004).

Gilar et al. (2020) previously compared the nonlinear and linear solvent strength models and found that the linear model can serve as an estimate for the prediction of analyte retention. The nonlinear model was implemented to try to correct the experimentally observed nonlinear concave behaviour in the \(\ln k_{i}\) versus solvent strength plots. The origin of this nonlinear behaviour in RP liquid chromatography is still not fully understood.

The analytes used in modelling are usually divided into two sets: a training set containing analytes that are directly integrated into the model, and a test set with analytes that are not used to construct the model. The latter serve as data, used to evaluate the generalization error of a model. The training error is determined using the training set. Together, these two metrics provide evaluation about the performance of the model. An ideal theoretical model has a low training error for analytes used in training the model and a low degree of generalization error for analytes added to the model for testing (Spears et al. 2018).

Solubility parameters

Hansen solubility parameters (HSP) are empirical thermodynamic parameters that aim to quantify the notion of “like dissolves like” (Hansen 1967). The core idea of HSP is summarized in Eq. 1, where a clear distinction of three basic molecular interaction types can be seen: dispersion interactions (d), polar interactions (p), and hydrogen bonding interactions (h).

The sum of the three partial solubility parameters represents the total solubility parameter \(\delta\), which is defined as the square root of the cohesion energy density i.e. the energy originating from intermolecular interactions divided by the molar volume, Eq. 2, (Hildebrand 1949).

Hansen distance is a numerical value that quantifies the thermodynamic similarity of two analytes based on the strength of the constituent interaction types. A Hansen distance for two analytes can be calculated from their respective HSP, Eq. 3.

HSP’s were developed mainly for predicting the solubility of paints, resins, and polymer components (Hansen 1967). They can be used in the development and study of the mechanical properties of thermoplastic-lignin composites (Zhao et al. 2018b, a). Their use in the pharmaceutical industry includes predicting the solubility of pharmaceutical excipients (Adamska et al. 2007) and the compatibility of biopolymers (Adamska et al. 2016). Sánchez-Camargo et al. have reviewed the use of HPS to predict solubilities for the selection of more environmentally acceptable extraction solvents (Sánchez-Camargo et al. 2019). The work of Schoenmakers et al. (1982), Schoenmakers and de Galan (1981) shows that there is a mathematical relationship between the solubility parameter and the chromatographic activity coefficients that allows a theoretical derivation of retention as a function of solubility parameters for all analytes and phases in chromatographic separations.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study is twofold. First, to formally derive and investigate a novel LFER physicochemical model for modelling and predicting RP chromatographic separations based on Hansen solubility parameters using the experimental retention data obtained with a series of three homologous phthalates. Secondly, to investigate the training error and generalization error of the model using a retention information dataset of chemically different analytes that have a similar aromatic structural component with different functional groups, in order to evaluate the model as a tool for routine retention prediction of analytes.

Results and discussion

Derivation of the model equation

The primary objective of the study is to develop and provide a detailed mathematical and theoretical derivation of the model. The model derivation begins with the mathematical treatment of retention equilibria occurring during RP chromatographic separations. After the analyte, denoted by the index \(i\), is introduced into the MP, the dynamic equilibrium between the activities of the analyte, corresponding to both phases, denoted by \({\mathcal{S}}\) for the SP and \({\mathcal{M}}\) for the MP, is formed, Eq. 4.

The dynamic equilibrium can be described by its equilibrium constant, Eq. 5.

The retention factor is a function of the chromatographic equilibrium constant, Eq. 6.

Combining Eqs. 5 and 6, with the formal definition for activity being the product of the molar concentration and the activity coefficient, results in Eq. 7.

Schoenmakers et al. (1982), Schoenmakers and de Galan (1981) have previously related the chromatographic activity coefficient \(\gamma_{i}\) with solubility parameters \(\delta\), Eq. 8, with the subscript f indicating the phase.

Combination of Eqs. 7 and 8 and replacement of the molar volume and the universal gas constant with the cavitation volume and Boltzmann constant, due to the theoretical treatment of single molecules during the DFT cavitation volume calculations, results in

and after simplification

The natural logarithm of ki is presented in Eq. 9.

Then Hansen solubility parameters as Hansen distances are introduced

each encompassing the thermodynamic similarity between the analyte and the chromatographic phase. The Hansen distance for the analyte and SP is trivial to calculate, using the formal definition, Eq. 10.

As the mobile phase is composed of a mixture of water and ACN, the corresponding MP-analyte Hansen distance is more complicated to calculate. It was assumed that HSP of mixtures are equal to the weighted sums of all HSP of pure substances. The molar fraction is used as a weight. Using this, the Hansen distance for the combination of analyte and the MP becomes Eq. 11.

The molar fraction of a bicomponent mixture adds up to unity, thus enabling the transformation of Eq. 11 into Eq. 12, where x denotes the molar fraction of ACN.

Expanding the equation and factoring out the molar fraction, with further algebraical manipulation described in detail in the Additional file 1: section S1, leads to Eq. 13.

By combining the Hansen distances and Eq. 9, we arrive at Eq. 14.

Then the thermodynamic descriptor as Eq. 15 can be defined.

With the assumption that the second logarithm in Eq. 14 is constant and by implementing the thermodynamic descriptor, the central theoretical model Eq. 16 is derived.

The model is based on Eq. 16—a simple linear regression, with regression coefficients denoted as \(\beta\). The Hansen distances are calculated for each combination of SP, MP composition and analyte type, to obtain unique values of the thermodynamic descriptor. The analyte cavitation volume is calculated using theoretical DFT calculations, as described in the Materials and methods section. The model relates the theoretical thermodynamic descriptor \({\Xi }_{i}\), which encompasses the variables of column temperature, Hansen distances and analyte cavitation volumes, with the experimentally determined retention factor \(\ln k_{i}\).

Statistical analysis and general observations of the model

Plotting the theoretical thermodynamic descriptor \({\Xi }_{i}\) against the experimental \(\ln k_{i}\) reveals a pattern, which is presented in Fig. 1. Each point represents an average of three experimentally determined retention factors.

A clear distinction of the retention data of individual analytes (DMP, DEP and DBP) is observed including the formation of two groups corresponding to the two studied SP (C8 and C18). Furthermore, differently oriented bands of individual analyte within the SP groups are observed. The results indicate the lack of generality of the thermodynamic descriptor \({\Xi }_{i}\) for the complete description of structural variability as different retention behaviours for the investigated analytes are observed. A cumulative model, which includes all the data points, is therefore not theoretically justified. Hence six separate linear regression models were created, one for each analyte and the corresponding SP (singular models) and two cumulative models for all three analytes within the training set, but for separate SP.

Statistical data processing of the results is presented in Table 1 and complemented with regression coefficients presented in the Additional file 1: Table S1.

Residual analysis was performed to investigate their possible correlations, the results of which are presented in Fig. 2. The correlation between the residual values could be observed as a trend indicated by the yellow line, deviating from the horizontal zero line. The trends have the minima at data points corresponding to the experiments at the MP composition of 60 vol. % of ACN. The cumulative model (Fig. 2d) reveals even more pronounced residual correlations. Thus, according to these observations, the models are not linear, even though a positive p-value test suggests a linear relationship. The same trend was observed in the experiments with C18 SP.

Evaluation of the training error and generalization error

Regardless of the observed nonlinearity, the model’s training error was investigated. The predicted \(\ln k_{i}\) values were compared with experimentally gained values for DMP, DEP and DBP. Relative error and root mean squared error of prediction (RMSEP) of the retention time were calculated (Table 2).

The singular models that included only one analyte underestimated retention times, whereas the cumulative model for all three analytes at selected SP overestimated the retention times with larger deviations.

The evaluation of the generalization error with analytes from the test set revealed even greater differences (Table 3), which minimized the ability to predict retention times for analytes not used in the construction of the model.

The model can therefore hardly be generalized for retention prediction for chemically diverse analytes that are not intrinsically included in the model.

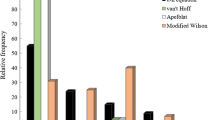

Comparison with solvent strength models

Unlike conventional retention modelling approaches that use isothermal experiments (Haddad et al. 2021), the HSP-based model includes column temperature as an independent variable used to calculate the thermodynamic descriptor. The residual standard error (RSE) value was calculated for each model (Fig. 3) to compare the novel theoretical model with conventional linear and nonlinear solvent strength models. All metrics of model quality and regression coefficients are presented in Additional file 1: Tables S2–S4. Data obtained at 25 °C were used, except for the model that included all three column temperatures. The solvent strength models achieve a lower RSE value for singular analyte models. Their RSE values for cumulative models are much higher than the values of the HSP model. The HSP model is therefore more suitable compared to the conventional solvent strength model when several analytes are modelled simultaneously. The low values of RSE for singular solvent strength models and their higher values for the cumulative models could indicate a greater degree of overfitting of the retention data.

Exploring beyond the theoretical model

Nonlinearity was further investigated with multiple linear regression. In addition to the thermodynamic descriptor, the column temperature and the total adsorption of ACN on the C18 SP, based on data from Buntz et al. (Buntz et al. 2012), were used as independent variables. The nonlinear model is described by Eq. 17.

where A denotes the total molar adsorption of ACN on the SP. Since data for the total adsorption of ACN was only available for the C18 and not for the C8 SP, the models were built only for data collected with the corresponding C18 column.

The results of the statistical analysis of the multiple regression model, presented in Table 4, reveal an improvement in the statistical regression measure of quality, mainly as a decrease in the RSE values compared to values presented in Table 1. Regression coefficients are reported in the Additional file 1: Table S5. A consecutive statistical residual analysis (reported in the Additional file 1: Figure S1) revealed a nonlinear correlation of the residuals, indicating that the independent variables used in this model do not fully describe the chromatographic separation model, analogous to the theoretical model equation using a simple linear regression.

A statistical investigation of the experimental-only retention data provided insight into the observed nonlinear anomaly. The differences in retention between the three temperatures at a fixed MP composition are presented in Fig. 4. First, a general trend is observed in the effect of temperature and MP composition on retention. Increasing the ACN content in MP decreases the extent to which a change in temperature affects the \(\ln k_{i}\) for all three analytes in the training set, which is evident from the interpolated trends. Second, an anomalous retention is observed at 60 vol. % of ACN. The anomaly coincides with the minima observed in simple linear and multiple linear regression models. The trends for DMP and DEP are similar, while DBP shows a slightly different pattern with increasing ACN content. The general trend is observed for both investigated SP.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a novel theoretical model for predicting the retention of analytes in RP chromatographic separations, together with a complete mathematical derivation of the central model equation. To date, this is the first study to use Hansen solubility parameters as possible thermodynamic descriptors for predicting retention behaviour in RP HPLC. We have found that Hansen solubility parameters cannot satisfactorily describe multiple chemical interactions that occur in RP chromatographic separations. The theoretical model combining HSP with theoretically derived solute cavitation volumes is not applicable for the routine prediction of analyte retention times, due to an unfavourable training and generalization error. Moreover, the assumed linear relationship proves to be statistically unjustifiable. Incorporating the thermodynamics of dissolution and mixing, as suggested by Louwerse et al. (Louwerse et al. 2017), could lead to the development of a more accurate HSP based theoretical model. Although, a comparison with conventional solvent strength models reveals that the HSP model is better at simultaneously predicting the retention of multiple analytes with only one regression model. This represents a shift from various model development methods in which multiple regression equations corresponding to each analyte under study are created to describe retention behaviour (McEachran et al. 2018). A multiple linear regression model was also performed, including additional independent variables such as column temperature and total adsorption of ACN to the SP, to investigate the origin of the nonlinear behaviour deviating from the theory. The nonlinearity was still observed. To verify that the observed anomaly is not an artefact of the model, the numerical differences in the experimental retention data were calculated. A correlation was found between change in MP composition and temperature on retention. The anomaly at the MP composition of 60 vol. % ACN is again observed, raising an open research question about the origin of the surveyed nonlinear anomaly.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Diethyl phthalate (DEP) (99.5%), dimethyl phthalate (DMP) (≥ 99%), dibutyl phthalate (DBP) (99%), 3-methylbenzoic acid (99%), 2,4,6-triiodophenol (97%), uracil (99%) and benzaldehyde (≥ 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany) and vanillin (99%) from Merck (Germany). Acetonitrile (ACN) (Fischer Scientific, UK, ≥ 99.9%) and deionised water, purified with the Mill-Q® system, were used as chromatographic solvents.

1 mg mL−1 stock solutions of DMP, DEP, DBP, benzaldehyde, 2,4,6-triiodophenol, 3-methylbenzoic acid and vanillin were prepared in ACN. A 1 mg mL−1 stock solution of uracil was prepared in deionised water. 10 mg L−1 solutions of investigated analytes were prepared by dilution with ACN. To each solution, uracil was added at a concentration of 10 mg L−1, which was used as a marker for the void time. Its determination using uracil was previously described as an acceptable estimation technique (Bidlingmeyer et al. 1991; Rimmer et al. 2002).

Instrumental conditions

The HPLC experiments were carried out on an Agilent Technologies system 1100 with degasser, quaternary pump, auto-sampler, column thermostat and a diode array detector. Two RP columns were used; YMC Triart C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, pore size of 12 nm) and YMC Triart C8 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, pore size of 12 nm). All chromatographic separations were isocratic, with a constant flow of 1 mL min−1. Absorption spectra were recorded with a diode array detector in the spectral range from 210 to 400 nm at a collection frequency of 5 Hz.

Experimental design for data acquisition

Retention data for uracil, DMP, DEP and DBP using the solution in ACN were collected using a full factorial experimental design by varying the column temperature (25, 35 and 45 °C), MP composition (40, 50, 60, 70, 80 vol. % ACN) and the SP (C8 and C18). Each data point was collected three times, by repeating the full factorial experimental sequence.

The solutions of analytes in the training and test sets were used in HPLC experiments at 25 °C on the C8 SP at 65, 75 and 85 vol. % of ACN in the MP for the collection of data, used in the investigation of the training error and the generalization error of the model. All retention data are presented in the Additional file 1: Tables S6–S12.

Ab initio density functional theory calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were implemented using GAMESS (version R2 September 30, 2020 for Microsoft Windows) (Barca et al. 2020) and the graphical interface software Winmostar (Winmostar—Student V10.1.3 for 64bit Windows). The B3LYP hybrid functional was used. The geometry was preliminarily optimized using a smaller 3-21G* basis set, followed by an aug-cc-pVTZ basis set for the final optimization. Water was simulated using the polarizable continuum model (Mennucci 2012) for the determination of solute cavitation volumes. The calculated analyte cavitation volumes are listed in the Additional file 1: Table S13.

HSP calculation

Analyte HSP were calculated according to the group contribution method described by Stefanis and Panayiotou (2012, 2008). Utilizing this technique, each analyte molecule is broken down into discrete first-order molecular fragments i.e. aromatic ArC-H, methyl -CH3 and ester COO fragments. After identifying all first-order molecular fragments, second-order fragments can be identified. These include resonance stabilized functional groups i.e. aromatic ester ArCCOO fragments. Once a molecule is described by first- and second-order fragments, the dispersion, polar and hydrogen bond contributions for each fragment are summed. These sums are consecutively modified by adding terms, derived by regression of a large set of experimentally determined HSP parameters. n-octane and n-octadecane were used as SP approximations and their HSP were calculated using the same method. The calculated HSP are presented in the Additional file 1: Table S14. HSP for deionised water and ACN, Additional file 1: Table S15, were collected from tabulated experimental data, provided by Hansen (2007).

Statistical analysis and model construction

All statistical analyses were implemented using R (ver. 4.0.2) within Rstudio (ver. 1.3.1056). R was also used in the production of the figures. The retention prediction model was implemented using Python (ver. 3.6.1) within PyCharm (2019.3.5 Professional Edition).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analysed in this study have been provided in the manuscript and the supporting information.

Abbreviations

- RP:

-

Reversed-phase

- SP:

-

Stationary phase

- MP:

-

Mobile phase

- LFER:

-

Linear free-energy relationship

- HSP:

-

Hansen solubility parameters

- DEP:

-

Diethyl phthalate

- DMP:

-

Dimethyl phthalate

- DBP:

-

Dibutyl phthalate

- ACN:

-

Acetonitrile

- DFT:

-

Density functional theory

- RMSEP:

-

Root mean square error of prediction

- RSE:

-

Residual standard error

- \({\mathcal{S}}\) :

-

Index representing the SP

- \({\mathcal{M}}\) :

-

Index representing the MP

- \(i\) :

-

Index representing a general analyte

- \(j\) :

-

Index representing a general component of the MP

- \(d\) :

-

Index representing dispersion partial solubility parameters

- \(p\) :

-

Index representing polar partial solubility parameters

- \(h\) :

-

Index representing hydrogen bonding partial solubility parameters

References

Abraham MH, Ibrahim A, Zissimos AM. Determination of sets of solute descriptors from chromatographic measurements. J Chromatog a. 2004;1037:29–47.

Adamska K, Voelkel A, Héberger K. Selection of solubility parameters for characterization of pharmaceutical excipients. J Chromatog a. 2007;1171:90–7.

Adamska K, Voelkel A, Berlińska A. The solubility parameter for biomedical polymers—application of inverse gas chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;127:202–6.

Amos RIJ, Haddad PR, Szucs R, Dolan JW, Pohl CA. Molecular modeling and prediction accuracy in Quantitative Structure-Retention Relationship calculations for chromatography. Trends Anal Chem. 2018;105:352–9.

Barca GMJ, Bertoni C, Carrington L, Datta D, De Silva N, Deustua JE, et al. Recent developments in the general atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J Chem Phys. 2020;152:154102.

Bidlingmeyer BA, Warren FV, Weston A, Nugent C, Froehlich PM. Some practical considerations when determining the void volume in high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr Sci. 1991;29:275–9.

Buntz S, Figus M, Liu Z, Kazakevich YV. Excess adsorption of binary aqueous organic mixtures on various reversed-phase packing materials. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1240:104–12.

Gilar M, Hill J, McDonald TS, Gritti F. Utility of linear and nonlinear models for retention prediction in liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2020;1613:460690.

Haddad PR, Taraji M, Szucs R. Prediction of analyte retention time in liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 2021;93:228–56.

Hansen CM. The three dimensional solubility parameter—key to paint component affinities I.—Solvents, plasticizers, polymers, and resins. J Paint Technol. 1967;39:104–17.

Hansen CM. Hansen solubility parameters: a user’s handbook. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007.

Hildebrand JH. A critique of the theory of solubility of non-electrolytes. Chem Rev. 1949;44:37–45.

Horváth C, Melander W, Molnár I. Solvophobic interactions in liquid chromatography with nonpolar stationary phases. J Chromatog a. 1976;125:129–56.

Louwerse MJ, Maldonado A, Rousseau S, Moreau-Masselon C, Roux B, Rothenberg G. Revisiting Hansen solubility parameters by including thermodynamics. ChemPhysChem. 2017;18:2999–3006.

McEachran AD, Mansouri K, Newton SR, Beverly BEJ, Sobus JR, Williams AJ. A comparison of three liquid chromatography (LC) retention time prediction models. Talanta. 2018;182:371–9.

Mennucci B. Polarizable continuum model. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2012;2:386–404.

Moldoveanu S, David V. Estimation of the phase ratio in reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatog a. 2015;1381:194–201.

Neue UD, Kuss H-J. Improved reversed-phase gradient retention modeling. J Chromatog a. 2010;1217:3794–803.

Ovčačíková M, Lísa M, Cífková E, Holčapek M. Retention behavior of lipids in reversed-phase ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1450:76–85.

Poole CF. An interphase model for retention in liquid chromatography. J Planar Chromatogr Mod TLC. 2015;28:98–105.

Poole CF. Influence of solvent effects on retention of small molecules in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 2019;82:49–64.

Rimmer CA, Simmons CR, Dorsey JG. The measurement and meaning of void volumes in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2002;965:219–32.

Sahu PK, Ramisetti NR, Cecchi T, Swain S, Patro CS, Panda J. An overview of experimental designs in HPLC method development and validation. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;147:590–611.

Sánchez-Camargo AP, Bueno M, Parada-Alfonso F, Cifuentes A, Ibáñez E. Hansen solubility parameters for selection of green extraction solvents. Trends Anal Chem. 2019;118:227–37.

Schoenmakers PJ, de Galan L. Systematic study of ternary solvent behaviour in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 1981;218:261–84.

Schoenmakers PJ, Billiet HAH, de Galan L. The solubility parameter as a tool in understanding liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 1982;15:205–14.

Snyder LR, Dolan JW, Carr PW. The hydrophobic-subtraction model of reversed-phase column selectivity. J Chromatog a. 2004;1060:77–116.

Spears BK, Brase J, Bremer P-T, Chen B, Field J, Gaffney J, et al. Deep learning: a guide for practitioners in the physical sciences. Phys Plasmas. 2018;25:080901.

Stefanis E, Panayiotou C. Prediction of hansen solubility parameters with a new group-contribution method. Int J Thermophys. 2008;29:568–85.

Stefanis E, Panayiotou C. A new expanded solubility parameter approach. Int J Pharm. 2012;426:29–43.

Tyteca E, Desmet G. On the inherent data fitting problems encountered in modeling retention behavior of analytes with dual retention mechanism. J Chromatog a. 2015;1403:81–95.

Vailaya A. Fundamentals of reversed phase chromatography: thermodynamic and exothermodynamic treatment. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2005;28:965–1054.

Zhao G, Ni H, Jia L, Ren S, Fang G. Quantitative analysis of relationship between Hansen solubility parameters and properties of alkali lignin/acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene blends. ACS Omega. 2018a;3:9722–8.

Zhao G, Ni H, Ren S, Fang G. Correlation between solubility parameters and properties of alkali lignin/PVA composites. Polymers. 2018b;10:290.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from EU Horizon 2020 APACHE project and the Slovenian Research Agency.

Funding

European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program: APACHE project Grant Agreement No. 814496. Slovenian Research Agency: research core funding No. P1-0153.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DR designed and conducted the experiments, derived the theoretical model, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. TR assisted with the experiments and revised the manuscript. IKC supervised the research and provided a critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Supporting information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ribar, D., Rijavec, T. & Kralj Cigić, I. An exploration into the use of Hansen solubility parameters for modelling reversed-phase chromatographic separations. J Anal Sci Technol 13, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-022-00322-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-022-00322-9