Abstract

Although Ficus-associated wasp fauna have been extensively researched in Australasia, information on these fauna in Taiwan is not well accessible to scientists worldwide. In this study, we compiled records on the Ficus flora of Taiwan and its associated wasp fauna. Initial agronomic research reports on Ficus were published in Japanese in 1917, followed by reports on applied biochemistry, taxonomy, and phenology in Chinese. On the basis of the phenological knowledge of 15 species of the Ficus flora of Taiwan, recent research has examined the pollinating and nonpollinating agaonid and chalcid wasps (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). Updating records according to the current nomenclature revealed that there are 30 taxa (27 species) of native or naturalized Ficus with an unusually high proportion of dioecious species (78%). Four species were observed to exhibit mutualism with more than one pollinating wasp species, and 18 of the 27 Ficus species were reported with nonpollinating wasp species. The number of nonpollinating wasp species associated with specific Ficus species ranges from zero (F. pumila) to 24 (F. microcarpa). Approximately half of the Taiwanese fig tree species have been studied with basic information on phenology and biology described in peer-reviewed journals or theses. This review provides a solid basis for future in-depth comparative studies. This summary of knowledge will encourage and facilitate continuing research on the pollination dynamics of Ficus and the associated insect fauna in Taiwan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Introduction

The pantropical genus Ficus (Moraceae) is the most speciose genus of woody plants, comprising 735 species known worldwide (Berg and Corner [2005]). Ficus is characterized by their unique inflorescences, called figs, or syconia. Due to their essential role in tropical landscapes and their rich ecological relationships with numerous invertebrates and vertebrates, fig trees may be considered as keystone resources of tropical forests (Shanahan et al. [2001]; Harrison [2005]). Asia contains a wide diversity of Ficus flora, with 130 known species from Borneo (Berg and Corner [2005]), 99 from China (Wu et al. [2003]) and only 25 species common to the two areas.

The genus has attracted considerable attention among ecologists because of its obligate mutualism with pollinating wasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae: Agaoninae, Kradibiinae, Tetrapusiinae) (Cruaud et al. [2010]; Heraty et al. [2013]). Fig trees have become an essential model for studies on mutualism (Janzen [1979]; Frank [1985]), sex ratio theory (Herre [1985]; Weiblen [2002]), and coevolution processes (Anstett et al. [1997]; Cook and Rasplus [2003]).

Fig trees and their pollinators have long been used as an example of obligate mutualism. The pollinating wasps are the only organism pollinating the figs and these wasps can only lay eggs in fig ovules. The pollinators enter into the fig by a tight ostiole. Once inside the fig, wasps pollinate the flowers and lay eggs inside the fig ovules (Kjellberg et al. [2005]). Then the larvae feed on gall tissue induced during the oviposition and mature along with the seeds and pollen grains of the fig. At maturity, fertilized female pollinating wasps leave the natal fig and transport pollen to another receptive fig on another tree (Kjellberg et al. [2005]). Some pollinating fig wasps genera actively pollinate the styles of the ovules before oviposition. After mating, they open the anthers of their natal fig and collect pollen grains that are stored in pollen pockets located on the ventral side of the mesosoma (Kjellberg et al. [2001]). In contrast, passive pollination requires no specific behavior: The pollen grains simply stick to the wasp body and fertilize ovules when the pollinating wasps enter a fig. Though one Ficus species is associated with only one pollinating wasp species in most of the cases (Janzen [1979]), some Ficus species have long been known to host additional pollinating wasp species (Galil and Eisikowitch [1967]; Ramírez [1970]; Molbo et al. [2003]).

In addition to the pollinating wasp species, most of the Ficus species also host nonpollinating wasp species (Kjellberg et al. [2005]). These wasps oviposit from the outside of the figs. The number of nonpollinating wasps (NPFW) species varies greatly between Ficus species (Kerdelhué et al. [2000]). Their feeding regimes also vary: Some NPFW species gall the ovules similarly to the pollinating species, and some are parasitoids (Compton and van Noort [1992]).

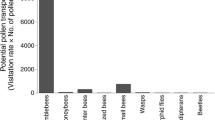

Over the past century, extensive research on various characteristics of the fig flora in Taiwan and its associated fauna has been conducted (Figure 1). Taiwan and its offshore islands are tropical and subtropical. Recently, 26 native and one introduced Ficus species have been reported (Tzeng [2004], in Chinese with English abstract). The first report on the Ficus genus in Taiwan was written in Japanese and focused on the cultivation of Ficus pumila var. awkeotsang (Takao [1917]). The first taxonomic monograph was published in 1934 (Sata [1934]), followed 10 years later, by a comparison of the fig flora in Taiwan and in the Philippines (Sata [1944]). Later on, several studies addressing the biochemistry of an edible jelly produced from the dried seeds of F. pumila var. awkeotsang (Huang and Chen [1979]; Huang et al. [1980]; Lin et al. [1989]; Liu et al. [1989], [1990]) were published. This jelly, locally called “aiyu”, is a common ingredient of summer beverages in Taiwan.

Taiwanese publications on fig and fig wasps since 1979. Each Taiwanese article has been classified under a discipline in which the journal they have been published in. The categories are the ones used in the ISI Web of KnowledgeSM. Nevertheless 18 of the 24 cited journals were not referenced by ISI Web of KnowledgeSM then they have been categorized according to the journal description. For the journals having more than one category, value has been divided in equal parts. For example, a journal categorized in Forestry and Ecology would have counted as 0.5 in the two categories for this graph.

Taxonomic research on the Ficus genus in Taiwan resumed 45 years after Sata’s final publication (Liao [1989]), which has been recently updated by Tzeng ([2004]). The research performed by Tzeng ([2004]) is exhaustive and provides a clear understanding of the Ficus flora and its distribution around Taiwan.

The phenology of Ficus has been extensively studied (Hu et al. [1986]; Ho [1987]). Phenological research introduced a physiological point of view to the study of fig ecology. However, common fig-wasp interactions have rarely been reported in Taiwan. We here establish a framework for future work on Taiwan Ficus and its associated wasp fauna by providing an updated list of Ficus species and the associated wasp species in Taiwan. These wasp species include specific pollinators or groups of pollinator species (in a few cases) as well as nonpollinating fig wasps.

As part of a previous field study (Bain [2012]), we collected figs from various sites throughout a lowland forest habitat on Taiwan as well as on Orchid and Green Islands off the southeast coast of Taiwan.

Notes on the taxonomy of Ficus(Moraceae)

In this present review, historical records were updated according to the current taxonomy and nomenclature guidelines to list 27 fig species (one species more than previously recorded) and 30 distinct taxa associated with the six subgenera present in Taiwan: Urostigma (5 taxa), Pharmacosycea (2), Ficus (8), Synoecia (6), Sycidium (6), and Sycomorus (3) (Table 1).

Several species names from the studies of Liao ([1989], [1995]) and Tzeng ([2004]) were updated according to the recent taxonomic and nomenclatural knowledge. In the subgenus Urostigma, F. subpisocarpa has been subject to two recent revisions. Berg and Corner ([2005]) reinstated the species from F. superba var. japonica. Subsequently, by incorporating new observations from Thailand, Berg further divided the species into two subspecies: F. subpisocarpa subsp. pubipoda and F. subpisocarpa subsp. subpisocarpa (Berg [2007]). Based on this knowledge, the Taiwanese taxon is F. subpisocarpa subsp. subpisocarpa (hereafter called F. subpisocarpa). Several taxonomic questions for this subgenus group remain unanswered. For example, the taxonomic position of F. benjamina var. bracteata is unclear. In 1983, Yamazaki described F. benjamina var. bracteata from Taiwan for the first time; subsequently, Berg and Corner ([2005]) assigned it a synonym: F. benjamina. In the studies conducted by Berg and Corner ([2005]) and Corner ([1965]), the analyzed F. benjamina var. bracteata samples were not obtained from Taiwan. Our observations from southern Taiwan reveal differences between F. benjamina var. benjamina and F. benjamina var. bracteata (Bain and Tzeng, pers. obs.). Despite these differences, until further research provides a new basis for a decision, we continue to list F. benjamina var. bracteata as a variety according to descriptions provided by Tzeng ([2004]). In addition, F. religiosa was not listed as a native species in the report of Sata ([1934]), but as introduced to Taiwan. Nevertheless, because the pollinating wasp species of F. religiosa, Platyscapa quadraticeps, has been observed in Taiwan, we consider F. religiosa a naturalized species (Chen and Chou [1997]).

Two previously reported species of the subgenus Pharmacosycea from Taiwan have been reported (F. nervosa subsp. nervosa and F. nervosa subsp. pubinervis) have a debatable taxonomic status. Tzeng ([2004]) considered the aforementioned species as two distinct species whereas Berg and Corner ([2005]) listed them as subspecies. Both species are allopatric: F. nervosa subsp. nervosa is distributed in southern Taiwan and F. nervosa subsp. pubinervis is distributed only in Orchid Island (the island, located offshore on the Southeast of Taiwan Island, is also called Lanyu, 22°03’N; 121°32’E) (Tzeng [2004]). The fact that they are pollinated by different agaonid wasp species (Table 1) provides additional evidence for distinguishing them as different species. According to pollen, pyrena and leaf morphology evidence (Chuang [2000]; Tzeng [2004]; Tzeng et al. [2009]), F. nervosa subsp. nervosa and F. nervosa subsp. pubinervis are phylogenetically close, yet distinct species. Thus, in this study, we refer to F. nervosa subsp. nervosa and F. nervosa subsp. pubinervis as F. nervosa and F. pubinervis, respectively.

In the subgenus Sycidium, F. tinctoria subsp. swinhoei has been synonymized under F. tinctoria subsp. tinctoria (Berg and Corner [2005]). The distribution of the former taxon is limited to southern Taiwan and Orchid Island, whereas F. tinctoria is widely distributed throughout Australasia (Berg and Corner [2005]). Moreover, these two subspecies have different pollinators (J-Y Rasplus, pers. obs.). Therefore, on the basis of the study by Tzeng ([2004]), we continue to list F. tinctoria subsp. swinhoei as separated from F. tinctoria subsp. tinctoria. Ficus tinctoria and F. virgata are two species that require further taxonomic investigation. After solely studying herbarium samples, Berg and Corner ([2005]) could not clearly distinguish between Taiwanese F. tinctoria and F. virgata. However, according to local field observations, F. virgata can be clearly and unambiguously distinguished from other Ficus species (Liao [1989], [1995]; Tzeng [2004]). Thus, Taiwanese F. virgata and F. tinctoria subsp. swinhoei are here considered distinct species.

Furthermore, in the subgenus Ficus, F. esquiroliana has been synonymized under F. triloba subsp. triloba (Berg [2007]). We support this decision because we found morphologically similar trees in Yunnan, China, and Taiwan (Bain and Tzeng, pers. obs.).

In addition, F. benguetensis (subgenus Sycomorus) has been reinstated as a full species (Tzeng [2004]; Berg and Corner [2005]). Previously, F. benguetensis was considered a variety, F. fistulosa var. benguetensis (Liao [1989], [1995]); in addition, Berg ([2011]) amended its description.

Finally, F. aurantiacea var. parvifolia (subgenus Synoecia) has been synonymized under F. punctata (Berg and Corner [2005]). Two forms of F. aurantiacea var. parvifolia have been described. The taxon distributed in Taiwan is listed under the “aurantiacea form” (i.e., F. punctata f. aurantiacea) (Chou and Yeh [1995]).

Morphological studies have facilitated the confirmation of the classification of Taiwanese Ficus (Shieh [1964]; Chuang [2000]; Tseng et al. [2000]; Bai [2002]; Chuang et al. [2005]; Chang et al. [2009]; Tzeng et al. [2001], Tzeng et al. [2005b], Tzeng et al. [2006a], Tzeng et al. [2009]). Among these studies, pollen (Tzeng et al. [2009]) and pyrena (Chuang [2000]; Chuang et al. [2005]; Tzeng et al. [2006a]) morphologies were interpreted systematically. For example, the morphology of pyrena (fig seed) is different for each Ficus subgenus. Moreover, the rough surface of the Ficus from the subgenus Sycomorus can be linked with their dispersers: Fruit bats (Lee et al. [2009]). Pollen shape lends insight into pollination patterns. Emarginate-ellipse and truncate-ellipse pollen types indicate passive pollination, whereas the truncate-rhombus pollen type indicates active pollination (Kjellberg et al. [2001]).

Phenology, ecology, and biology of figs and fig wasps

Ficus ecology, particularly the interspecific mutualism between Ficus and fig wasps, began to receive attention in the early 1990s. Since then, several studies on this interspecific mutualism have been conducted (see Kjellberg et al. [2005] for review).

Prior knowledge of phenology is essential for studies on mutualism. Ficus trees differ from most of other tree species: the figs they produced host their mutualistic pollinators. Thus the Ficus reproductive phenology is not constant as other tree species (Bain et al. [2014a]) that are, for example, bound to seasons (spring bloom). Numerous phenological studies of Ficus trees have been conducted in Taiwan. The subgenus Urostigma includes monoecious taxa, whereas all other subgenera in Taiwan are dioecious, having separate male and female trees. The latter produce only seeds whereas the figs of the former produce both pollen and pollen dispersers (pollinating fig wasp). Among the six subgenera in Taiwan, phenological data on all subgenera, except for the subgenus Pharmacosycea, have been collected. Finally, among the 30 Ficus taxa, only half of them have seen their phenology examined. The most studied taxon is F. erecta var. beecheyana, which has been described in six reports. In Taiwan, most phenological research has been undertaken as a part of graduate thesis work, and, therefore, is found mainly in Chinese language theses and remains unpublished in peer-reviewed journals. Nevertheless, data from this phenological research provides a strong basis for further study.

The monoecious F. microcarpa has been a study subject of four theses in Taiwan (Hsieh [1992]; Chen [1994]; Chen [2001]; Yang [2011]). Ficus microcarpa is the most studied species worldwide because of its common occurrence in cities and campuses, and its invasive status in several continents (Beardsley [1998]; Farache et al [2009]; Doğanlar [2012]). Reports on fig production are in agreement with the aforementioned studies. Each of these three studies surveyed the F. microcarpa population on the National Taiwan University campus in different years. Fig trees were found to bear figs almost constantly throughout the year, with a decrease in fig yield observed from the beginning of autumn (Hsieh [1992]; Yang et al. [2013]) and some years, no figs were observed on the trees (Chen et al. [2004]). In all of the aforementioned studies, the fig yield was the lowest in the winter season. Moreover, the number of crops per year varied greatly from zero to four. In addition, fig bearing in the F. microcarpa population was highly asynchronous as no distinct seasonal or annual pattern was identified in any of the studies. However, the genetic diversity seems to determinate the phenological diversity of the F. microcarpa trees (Yang et al. [2014]).

In addition to F. erecta, numerous dioecious species have been surveyed to determine fig production patterns (Tzeng et al. [2003], [2005a]; [2006b]; Bain et al. [2014a]). In northern Taiwan, dioecious species were found to have similar phenological patterns across the genus. First, male trees consistently began bearing figs at the beginning of spring every year; female trees began their fig productiona few weeks later. Second, a noticeable second production peak occurred in September and October. Third, rarer winter figs have a longer maturation period. Similar to the F. microcarpa population, other fig tree populations produced figs asynchronously. Although there was a peak production period, the production of figs was not simultaneous. The production of some trees can be delayed for a few weeks (Yao [1998]; Bain et al. [2014a]). After the spring crop, the populations bore a low number of figs until autumn, when the male trees again preceded the female trees with a production few weeks earlier. Finally, in winter, the trees were barest throughout Taiwan (Ho [1991]; Chen [1998]; Yao [1998]; Chang [2003]; Huang [2007]; Ho et al. [2011]; Chen [2012]; Chiu [2012]; Bain et al. [2014a]).

Nevertheless, some inter- and intraspecific variations were observed. The duration of the spring crop and the proportion of male trees producing figs between the two crop peaks differed between species. Also the synchrony between male and female tree peaks of fig production varied greatly. Throughout most of the island of Taiwan, Ficus tree populations were found to crop during a long period in spring. A considerable proportion of male trees produce figs throughout the year (Ho [1991]; Chen [1998]; Yao [1998]; Chang [2003]; Huang [2007]; Ho et al. [2011]; Chen [2012]; Chiu [2012]; Bain et al. [2014a]). At low altitudes in the extreme north, male trees have shorter spring crops than those in the south. The percentage of male trees producing figs between the two peak seasons is lower in the north than that in the south of Taiwan (Bain et al. [2014a]). Finally, at higher altitudes, the production peaks of male trees during spring are extremely short and are synchronous within a population, with few male trees bearing figs between the two seasonal peaks (Wu [1996]; Tzeng et al. [2003], [2006b]; Bain et al. [2014a]). The general island-wide pattern suggests that phenology has been shaped by environmental factors but constrained by mutualism: the short lifespan of the pollinating fig wasps requires the fig tree population to produce figs regularly (Bain et al. [2014a]). Under harsh environmental conditions, male trees can produce figs only during a short period as soon as spring conditions permit, whereas under mild environmental conditions, the fig production period is extended.

In Taiwan, biochemical studies on Ficus have centered on F. pumila var. awkeotsang, which produces an edible jelly, and the two varieties (var. pumila and var. awkeotsang) with morphological features have drawn research attention. The two varieties are morphologically close (Lin et al. [1990]; Tzeng [2004]). Because of the economic interest in the edible jelly produced from the dried seeds of F. pumila var. awkeotsang, the biochemical and nutritional composition of the jelly has been established (Huang and Chen [1979]). Later, the compounds responsible for the jelly have been identified (Liu et al. [1990]). The vegetative reproduction characteristics of this species have also been reported (Liu et al. [1989]).

Pollinating fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae)

According to the phylogenetic nomenclature of Cruaud et al. ([2010]), we have noticed two changes in the former Taiwanese fig wasp nomenclature. First, the wasps belonging to the genus Blastophaga subgenus Valisia have been listed under the new genus Valisia. Therefore, pollinators of F. triloba and F. ruficaulis are now known as Valisia esquirolianae and V. filippina. Second, the genus Liporrhopalum has been synonymized under the genus Krabidia. Thus, all Agaonidae wasps pollinating the Ficus species from the subgenus Sycidium have been moved to the genus Krabidia (Table 1).

The study by Chen and Chou ([1997]) was one of the few studies that attempted to describe all pollinating wasp species from Taiwan. In their study, 24 species (seven newly described species) from eight genera were observed in Taiwan (Chen and Chou [1997]). Their study still observed the 1:1 species specificity rule between fig trees and pollinating wasps. However, recently, a genetic study on the pollinating wasp species of Ficus septica concluded that it has three pollinator species with different distributions in Taiwan (Lin et al. [2011]). One species was strictly limited to Orchid Island and the extreme south of Taiwan. The second species was limited only to Orchid Island and was considered rare. The third species was widely observed throughout Taiwan. Furthermore, genetic results showed weak differentiation among the fig wasp populations on the island, suggesting that the gene flow is high within the F. septica population in Taiwan (Lin et al. [2008]). This trend was previously observed in other Ficus species, fig wasps, and other locations (Compton et al. [2000]; Harrison and Rasplus [2006]; Ahmed et al. [2009]; Kobmoo et al. [2010]). In addition, Wiebesia pumilae and Wiebesia sp., the pollinators of F. pumila var. pumila and F. pumila var. awkeotsang, were morphologically and genetically distinct (Lee [2009]; Jiang [2011]). These two wasp species have been observed in the figs of both varieties of F. pumila (Lu et al. [1987]; Jiang [2011]).

In addition to taxonomic studies, since the late 1990s, studies on the population dynamics of pollinators associated with Ficus phenology have been conducted (Chen et al. [2004]). The most recent phenological study on F. microcarpa in Taipei City provided data on the size of the pollinating wasp population (Yang et al. [2013]). The population size varied greatly during a year. During winter, the pollination rate of figs was low whereas in summer the size of the pollinating wasp population was great and the number of foundresses could reach 19 in one single fig. These data have been used to estimate the total population of female wasps living around the studied group of F. microcarpa trees in Taipei (Yang et al. [2013]). Yang et al. ([2013]) showed marked variation in the dynamics of the foundress population size from 0 to 40,000 within one season for the 29 studied trees. Although there was a winter trough in the number of pollinators, the pollinator population could exhibit a high recovery rate in the spring season and still reach the peak during the summer-fall season.

Nonpollinating fig wasps (Hymenoptera)

Nonpollinating fig wasps (NPFWs) are categorized in three trophic categories: the gallers that induce a gall from the plant tissue, their larva feeds on the growing gall tissue; the parasitoids that lay their eggs on other larvae which feed on the host larva; and the kleptoparasites that kill galler larvae to feed on the induced gall tissues.

The NPFWs belong to three families (Eurytomidae, Ormyridae, and Torymidae) and seven subfamilies (Colotrechninae, Epichrysomallinae, Otitesellinae, Pteromalinae, Sycoecinae, Sycophaginae, and Sycoryctinae). The recent molecular phylogeny of the superfamily Chalcidoidea (Munro et al. [2011]), which includes all of the aforementioned groups, has shown that four groups are monophyletic (Agaonidae, Epichrysomallinae, Pteromalinae, and Sycophaginae), whereas the other groups are paraphyletic. In addition, phylogenies of the subfamilies Sycophaginae (Cruaud et al. [2011]) and Sycoryctinae (Segar et al. [2012]) have been established. As we previously modified the names of pollinating wasp species, we here display the names of the Taiwanese species on the basis of the recent updates (Cruaud et al. [2011]; Segar et al. [2012]). First, the genus Apocryptophagus forms a single taxon with the genus Sycophaga, and consequently, it has been considered a junior synonym of Sycophaga and then synonymized under the genus Sycophaga (Cruaud et al. [2011]). Therefore, the former Apocryptophagus wasps are currently named Sycophaga. Second, the Sycoscapter wasps once formed a group that was synonymized by Bouček ([1988]), all of the former names were reinstated by Segar et al. ([2012]): Sycoscapter, Sycoryctes, Arachonia, Sycoscapteridea, and Sycorycteridea. Nevertheless, some Sycoscapter wasps listed in Table 1 and cited from other studies may be still grouped under Sycoscapter sensu Bouček ([1988]).

The first and only taxonomic publication on Taiwanese NPFW addressed the F. microcarpa wasp community (Chen et al. [1999]). Studies examining NPFWs have been ecological studies, such as a study of the feeding regime (galler or parasitoid) of some Sycoscapter larvae (Tzeng et al. [2008]). Conversely, the ecology of Taiwanese NPFW has been thoroughly studied. First, regarding F. microcarpa, to determine whether some NPFW are galler species (gallers produce plant galls that contain a growth of tissue to feed their larvae), the fig ostiole (i.e., the only entry of the fig) was sealed to avoid the entry of the pollinating wasps (Chen et al. [2001]). Without the agaonid wasps, two NPFW species laid eggs inside the fig ovules from the outside: Odontofroggatia sp. (Epichrysomallinae) and Walkerella kurandensis (Otitesellinae). Chen et al. ([2001]) showed that these two species were undoubtedly gallers. Second, regarding F. formosana, the exclusion of the two Sycoscapter species showed that they had a negative effect on the pollinating wasp population (Tzeng et al. [2008]). In another study, Tzeng et al. ([2014]) showed that the fig wall thickness is a factor affecting the NPFW oviposition. Moreover, the timing of oviposition of these NPFW clearly indicated that the wasps were parasitoids.

Recent observations have shown that the NPFW species occurring on F. pedunculosa var. mearnsii belong to the genus Apocrypta (Bain, unpublished data). This genus was reported to feed on the larvae of pollinating wasps from the genus Ceratosolen (Ulenberg [1985]), all pollinators of the fig subgenus Sycomorus (Rønsted et al. [2005]). However, F. pedunculosa var. mearnsii belongs to the subgenus Ficus and is pollinated by Blastophaga wasps, but not by Ceratosolen wasps. Therefore, this observation is unexpected and should be further confirmed by studying more trees and by covering a larger area.

Finally, NPFWs are the prey of numerous ant species (Formicidae). Such ant species have been observed foraging inside figs of F. tinctoria subsp. swinhoei, F. septica, F. benguetensis, and F. subpisocarpa (Bain et al. [2014b]). Ants enlarged the wasp exit hole and entered inside the figs to prey on the remaining fig wasps. On F. subpisocarpa, ants live more closely on the tree nesting inside the living branches of the tree (Bain et al. [2012]). In these nests, numerous bodies of nonpollinating and pollinating wasps have been collected. Nevertheless, the foraging and hunting behaviors of the ants seem to be species dependent as wasp bodies have not been found in the nests of every ant species (Bain et al. [2012]).

Conclusion

This paper presents and organizes the abundant and previously difficult-to-access research data on Ficus species and fig wasps in Taiwan. This paper compiles data from internationally accessible English language journal articles as well as local theses and dissertations, mostly in Chinese. In addition, this paper includes data from recent research conducted by the authors of this paper and presents an elaborate picture of the insect communities living on fig trees. The number and diversity of fig wasp fauna as well as the wide taxonomical range of Ficus warrant further comparative studies on the insect communities. Moreover, the high proportion of dioecious species enables investigating the sexual differences and adaptations of the two sexes. In summary, this paper provides comprehensive information on Ficus flora and wasp fauna in Taiwan, establishing a basis for understanding fig wasp survival and interspecific interaction in community ecology. Compared with other regions in the world, Taiwan provides an excellent foundation for continued ecological investigations of Ficus species and their associated communities.

References

Ahmed S, Compton SG, Butlin RK, Gilmartin PM: Wind-borne insects mediate directional pollen transfer between desert fig trees 160 kilometers apart. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2009,106(48):20342–20347.

Anstett M-C, Hossaert-McKey M, Kjellberg F: Figs and fig pollinators: evolutionary conflicts in a coevolved mutualism. Trends Ecol Evol 1997, 12: 94–99.

Bai J-T: The systematic wood anatomy of the Ficus (Moraceae) in Taiwan. Master Thesis. National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan; 2002.

Bain A: Colonization and adaptations of Ficus in Taiwan. Dual-Degree PhD Dissertation. National Taiwan University & Université Montpellier 2, Taipei, Taiwan & Montpellier, France; 2012.

Bain A, Chantarasuwan B, Hossaert-McKey M, Schatz B, Kjellberg F, Chou L-S: A new case of ants nesting within branches of a fig tree: the case of Ficus subpisocarpa in Taiwan. Sociobiology 2012,59(1):415–434.

Bain A, Chou L-S, Tzeng H-Y, Ho Y-C, Chiang Y-P, Chen W-H, et al.: Plasticity and diversity of the phenology of dioecious Ficus species in Taiwan. Acta Oecologica 2014, 57: 124–134.

Bain A, Harrison RD, Schatz B: How to be an ant on figs. Acta Oecologica 2014, 57: 97–108.

Beardsley JW: Chalcid wasps (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) associated with fruit of Ficus microcarpa in Hawai'i. P Hawaii Entomol Soc 1998, 33: 19–34.

Berg CC (2007) Precursory taxonomic studies on Ficus (Moraceae) for theCruaud A, Jabbour-Zahab Flora of Thailand. Thai Forest Bull Bot 35:4–28 Berg CC (2007) Precursory taxonomic studies on Ficus (Moraceae) for theCruaud A, Jabbour-Zahab Flora of Thailand. Thai Forest Bull Bot 35:4–28

Berg CC: Corrective notes on the Malesian members of the genus Ficus (Moraceae). Blumea 2011, 56: 161–164.

Berg CC, Corner EJH: Moraceae ( Ficus ). In Flora Malesiana. Edited by: Nooteboom HP. National Herbarium Nederland, Leiden; 2005.

Bouček Z: Australasian Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera): a biosystematic revision of genera of fourteen families, with a reclassification of species. C.A.B, International, Wallingford, UK; 1988.

Bouček Z: The genera of chalcidoid wasps from Ficus fruit in the New World. J Nat Hist 1993, 27: 173–217.

Chang W-C: Floral phenology and pollination ecology of Ficus ampelas Burm. at Chiayi. Master Thesis. National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan; 2003.

Chang W-C, Lu F-Y, Ho K-Y, Tzeng H-Y: Morphology of syconium of Ficus ampelas Bunn. f. Q J Forest Res 2009,31(3):1–16.

Chen Y-R: Phenology and interaction of fig wasps and Ficus microcarpa L. Master Thesis. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 1994.

Chen Y-L: Studies of phenology and interactions between Ficus irisana and its fig wasps. Master Thesis. National Chung Hsing University, Taichung; 1998.

Chen Y-R: Population fluctuation and community ecology of Ficus microcarpa L. and its fig wasps. PhD Dissertation. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 2001.

Chen H-C: Seasonal changes on fig production and volatiles compounds of Ficus septica Burm. f. Master Thesis. National Chung Hsing University, Taichung; 2012.

Chen C-H, Chou L-Y: The Blastophagini of Taiwan (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae: Agaoninae). J Taiwan Mus 1997,50(2):113–154.

Chen Y-R, Chuang W-C, Wu W-J: Chalcid wasps on Ficus microcarpa L. in Taiwan (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). J Taiwan Mus 1999,52(1):39–79.

Chen Y-R, Chou L-S, Wu W-J: Regulation of fig wasps entry and egress: the role of ostiole of Ficus microcarpa L. Formos Entomol 2001, 21: 171–182.

Chen Y-R, Wu W-J, Chou L-S: Synchronization of fig ( Ficus microcarpa L. f.) abundance and pollinator ( Eupristina verticillata : Agaoninae) population dynamics in northern Taiwan. J Natl Taiwan Mus 2004,57(2):23–36.

Chiu Y-T: Phenology and population genetic variation of Ficus pedunculosa var. mearnsii. Master Thesis. National Chung Hsing University, Taichung; 2012.

Chou L-Y, Wong C-Y: New records of three Philotrypesis species from Taiwan (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae: Sycoryctinae). Chinese J Entomol 1997, 17: 182–186.

Chou L-S, Yeh H-M: The pollination ecology of Ficus aurantiaca var. parvifolia . Acta Zool Taiwan 1995,6(1):1–12.

Chuang J-C: Studies on the morphology of pyrenes of the fig species in Taiwan. Master Thesis, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung; 2000.

Chuang J-C, Tzeng H-Y, Lu F-Y, Ou C-H: Study on the morphology of pyrene of Ficus in Taiwan - Subgenus Eriosycea , Ficus and Synoecia . Q J Chinese Forest 2005, 38: 1–18.

Compton SG, van Noort S: Southern African fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea): resource utilization and host relationships. P K Ned Akad C Biol 1992,95(4):423–435.

Compton SG, Ellwood MDF, Davis AJ, Welch K: The flight heights of chalcid wasps (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea) in a lowland Bornean rain forest: fig wasps are the high fliers. Biotropica 2000,32(3):515–522.

Cook JM, Rasplus J-Y: Mutualists with attitude: coevolving fig wasps and figs. Trends Ecol Evol 2003, 18: 241–248.

Corner EJH: Check-list of Ficus in Asia and Australasia with keys to identification. Gard B Sing 1965, 21: 1–186.

Cruaud A, Jabbour-Zahab R, Genson G, Cruaud C, Couloux A, Kjellberg F, et al.: Laying the foundations for a new classification of Agaonidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea), a multilocus phylogenetic approach. Cladistics 2010,26(4):359–387.

Cruaud A, Jabbour-Zahab R, Genson G, Kjellberg F, Kobmoo N, van Noort S, et al.: Phylogeny and evolution of life-history strategies in the Sycophaginae non-pollinating fig wasps (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea). Evol Biol 2011, 11: 178–192.

Doğanlar M: Occurrence of fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) in Ficus carica and F. microcarpa in Hatay, Turkey. Turk J Zool 2012,36(5):721–724.

Farache FHA, VT O, Pereira RA: New occurrence of non-pollinating fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) in Ficus microcarpa in Brazil. Neotrop Entomol 2009,38(5):683–685.

Feng G, Huang D-W: Description of a new species of Odontofroggatia (Chalcidoidea, Epichrysomallinae) associated with Ficus microcarpa (Moraceae) with a key to species of the genus. Zootaxa 2010, 2335: 40–48.

Frank SA: Hierarchical selection theory and sex ratios. II. On applying the theory, and a test with fig wasps. Evolution 1985,39(5):949–964.

Galil J, Eisikowitch D: On the pollination ecology of Ficus sycomorus in East Africa. Ecology 1967,49(2):259–269.

Grandi G: Contributo alla conoscenza degli Agaonini (Hymenoptera, Chalcididae) di Ceylon e dell'India. B Lab Zool Portici 1916, 11: 183–234.

Grandi G: Diagnosi preliminari di Imenotteri dei fichi. Ann Mus Civ Stor Nat Genova 1921, 49: 304–316.

Grandi G: Imenotteri dei fichi dell fauna olarctica e Indo-malese. Ann Mus Civ Stor Nat Genova 1923, 51: 101–108.

Grandi G: Hyménoptères sycophiles récoltés à Sumatra et à Java par E. Jacobson. Descriptions préliminaires. Treubia 1926, 8: 352–364.

Grandi G: Hyménoptères sycophiles récoltés aux iles Philippines par C.F. Baker, i. Agaonini. Philipp J Sci 1927,33(3):309–329.

Grandi G: Una nuova specie di Blastophaga del Giappone. B Soc Entomol Ital 1927, 59: 18–24.

Harrison RD: Figs and the diversity of tropical rainforests. BioScience 2005,55(12):1053–1064.

Harrison RD, Rasplus J-Y: Dispersal of fig pollinators in Asian tropical rain forests. J Trop Ecol 2006, 22: 631–639.

Heraty JM, Burks RA, Cruaud A, Gibson GAP, Liljeblad J, Munro J, et al.: A phylogenetic analysis of the megadiverse Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). Cladistics 2013,29(5):466–542.

Herre EA: Sex ratio adjustment in fig wasps. Science 1985, 228: 896–898.

Hill DS: Fig-wasps (Chalcidoidea) of Hong Kong i. Agaonidae. Zool Verh 1967, 89: 1–55.

Hill DS: Revision of the genus Liporrhopalum Waterston, 1920 (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae). Zool Verh 1969, 100: 3–36.

Ho K-Y: Ecology of the pollinator, jelly fig wasp, Blastophaga pumilae Hill, with emphasis on the possibility of population establishment at low elevation. Chinese J Entomol 1987, 7: 37–44.

Ho K-Y: Pollination ecology of Ficus pumila L. var. awkeotsang (Makino) Corner and Ficus pumila L. var. pumila. Master Thesis. National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan; 1991.

Ho Y-C: Phenology of Ficus septica in Taichung. National Chung Hsing University, Taichung; 2009.

Ho Y-C, Tseng Y-H, Tzeng H-Y: The phenology of Ficus septica Burm. f. at Dakeng, Taichung. Q J Forest Res 2011,33(4):21–32.

Hsieh M-C: The symbiosis between fig wasps and Ficus microcarpa L. Master Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 1992.

Hu T-W, Liu C-C, Ho C-K: Natural variation of receptacle fruits of female jelly fig ( Ficus awkeotsang Makino). B Taiwan Forest Res Inst 1986, 1: 139–153.

Huang J-Q: The relationships between phenology and fig wasps of a dioecious Ficus tinctoria. Master Thesis. National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; 2007.

Huang Y-C, Chen W-P: On the material plant of awkeo-jelly: Ficus awkeotsang Makino its historical review and future prospects. J Chinese Soc Hort Sci 1979,25(4):103–111.

Huang YC, Chen WP, Shao YP: A study on the mechanism of gelatinization of awkeo-jelly. China Hort 1980, 4: 117–126.

Ishii T: Fig Chacidoids of Japan. Kontyu 1934,8(2):84–100.

Janzen DH: How to be a fig. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 1979, 10: 13–51.

Jiang S-H: Morphological differences between pollinating fig wasps of Ficus pumila L. var. pumila and var. awkeotsang (Makino) Corner and their asymmetric host specificity. Master Thesis. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 2011.

Kerdelhué C, Rossi J-P, Rasplus J-Y: Comparative community ecology studies on Old World figs and fig wasps. Ecology 2000,81(10):2832–2849.

Kjellberg F, Jousselin E, Bronstein JL, Patel A, Yokoyama J, Rasplus J-Y: Pollination mode in fig wasps: the predictable power of correlated traits. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 2001, 268: 1113–1121.

Kjellberg F, Jousselin E, Hossaert-McKey M, Rasplus J-Y: Biology, ecology, and evolution of fig-pollinating wasps (Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae). In Biology, ecology and evolution of gall-inducing arthropods. Edited by: Raman A, Schaefer W, Withers TM. Science Publishers, Inc., Enfield (NH) USA, Plymouth (UK); 2005:539–572.

Kobmoo N, Hossaert-McKey M, Rasplus J-Y, Kjellberg F: Ficus racemosa is pollinated by a single population of a single agaonid wasp species in continental South-East Asia. Mol Ecol 2010, 19: 2700–2712.

Lee H-H: Genetic differentiation between Ficus pumila var. pumila and Ficus pumila var. awkeotsang and their pollinators. Master Thesis. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 2009.

Lee Y-F, Takaso T, Chiang T-Y, Kuo Y-M, Nakanishi N, Tzeng H-Y, et al.: Variation in the nocturnal foraging distribution of and resource use by endangered Ryukyu flying foxes ( Pteropus dasymallus ) on Iriomotejima Island, Japan. Contrib Zool 2009,78(2):51–64.

Liao J-C: A taxonomic revision of the family Moraceae in Taiwan (2): Genus Ficus . Q J Chinese Forest 1989,22(1):117–142.

Liao J-C: The taxonomic revisions of the family Moraceae in Taiwan (II). Department of Forestry, College of Agriculture, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC; 1995.

Lin T-P, Liu C-C, Chen S-W, Wang W-Y: Purification and characterization of pectinmethylesterase from Ficus awkeotsang Makino achenes. Plant Physiol 1989, 91: 1445–1453.

Lin T-P, Liu C-C, Yang C-Y, Huang R-S, Lee Y-S, Chang S-Y: Morphological and biochemical comparison of syconium of Ficus awkeotsang and Ficus pumila . B Taiwan Forest Res Inst 1990,5(1):37–43.

Lin R-C, Yeung CK-L, Li S-H: Drastic post-LGM expansion and lack of historical genetic structure of a subtropical fig-pollinating wasp ( Ceratosolen sp. 1) of Ficus septica in Taiwan. Mol Ecol 2008, 17: 5008–5022.

Lin R-C, Yeung CK-L, Fong JJ, Tzeng H-Y, Li S-H: The lack of pollinator specificity in a dioecious fig tree: sympatric fig-pollinating wasps of Ficus septica in southern Taiwan. Biotropica 2011,43(2):200–207.

Liu C-C, Huang R-S, Hu T-W: Vegetative propagation of carrying-leaf-cutting from Ficus awkeotsang Makino. B Taiwan Forest Res Inst 1989,4(2):71–76.

Liu C-C, Lin T-P, Huang R-S, Lee M-S: Developmental biology of female syconium of Ficus awkeotsang Makino: changes in the quantities of pectinmethylesterase, pectin, methoxyl group and achene. B Taiwan Forest Res Inst 1990,5(3):209–216.

Lu F-Y, Ou C-H, Liao C-C, Chen M-A: Study of pollination ecology of climbing fig ( Ficus pumila L.). B Exp Forest Natl Chung Hsing Univ 1987, 8: 31–42.

Mayr G: Feigeninsecten. Ver Zool-Bot Gesell 1885, 35: 147–250.

Molbo D, Machado CA, Sevenster JG, Herre EA: Cryptic species of fig-pollinating wasps: implications for the evolution of the fig-wasp mutualism, sex allocation, and precision of adaptation. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100: 5867–5872.

Munro JB, Heraty JM, Burks RA, Hawks D, Mottern J, Cruaud A, et al.: A molecular phylogeny of the Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). PloS One 2011,6(11):e27023.

Ramírez WB: Host specificity of fig wasps (Agaonidae). Evolution 1970,24(4):680–691.

Rønsted N, Weiblen GD, Cook JM, Salamin N, Machado CA, Savolainen V: 60 million years of co-divergence in the fig–wasp symbiosis. P Roy Soc B 2005, 272: 2593–2599.

Sata T: An enumeration of Formosan Ficus . I J Trop Agr Soc Formos 1934, 6: 17–28.

Sata T: Classification of the species of Philippine island plants. 1: on Ficus (Moraceae), a comparative study of Ficus of the Philippine and Formosa. Res. Survey 143 and 144. Bureau of Foreign Affairs, Govt. Gen. Formosa; 1944.

Segar ST, Lopez-Vaamonde C, Rasplus J-Y, Cook JM: The global phylogeny of the subfamily Sycoryctinae (Pteromalidae): parasites of an obligate mutualism. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2012,65(1):116–125.

Shanahan M, So S, Compton SG, Corlett RT: Fig-eating by vertebrate frugivores: a global review. Biol Rev 2001, 76: 529–572.

Shieh W-C: Studies on the pollen grain morphology in the genus Ficus in Taiwan. J Sci & Eng 1964, 1: 67–73.

Takao Y: On the characteristics of pectate of Ficus pumila var. awkeotsang achenes. Res Rep Taiwan Gov-Gen Off 1917, 49: 1–6.

Tseng L-J, Ou CH, Lu FY, Tzeng H-Y: Study of the development and morphology of syconium of Ficus formosana . Q J Taiwan Mus 2000,22(3):55–68.

Tzeng H-Y: Taxonomic study of the genus Ficus in Taiwan. PhD Dissertation. National Chung-Hsin University, Taichung, Taiwan; 2004.

Tzeng H-Y, Ou C-H, Lu F-Y: Morphological study on the syconia of Ficus erecta var. beecheyana . Taiwan J Forest Sci 2001,16(4):295–306.

Tzeng H-Y, Ou CH, Lu FY: Syconium phenology of Ficus erecta var. beecheyana at Hue-Sun Forest Station. Taiwan J Forest Sci 2003,18(4):273–282.

Tzeng H-Y, Lu FY, Ou CH, Lu K-C, Tseng L-J: Phenology of Ficus formosana Maxim. at Guandaushi Forest Ecosystem. J Chinese Forest 2005, 38: 377–395.

Tzeng H-Y, Lu FY, Ou CH, Lu K-C, Tseng L-J: Syconia production of Ficus formosana Maxim. at Hue-Sun Forest Station. J Forest Sci 2005, 27: 45–60.

Tzeng H-Y, Chuang J-C, Ou CH, Lu FY: Study of the morphology of pyrenes of Ficus in Taiwan in the subgenera of Sycidium and Sycomorus . Taiwan J Forest Sci 2006, 18: 273–282.

Tzeng H-Y, Lu F-Y, Ou C-H, Lu K-C, Tseng L-J: Pollinational-mutualism strategy of Ficus erecta var. beecheyana and Blastophaga nipponica in seasonal Guandaushi Forest Ecosystem, Taiwan. Bot Stud 2006, 47: 307–318.

Tzeng H-Y, Tseng L-J, Ou C-H, Lu K-C, Lu F-Y, Chou L-S: Confirmation of the parasitoid feeding habit in Sycoscapter , and their impact on pollinator abundance in Ficus formosana . Symbiosis 2008, 45: 129–134.

Tzeng H-Y, Ou CH, Lu FY, Wang CC: Pollen morphology of Ficus L. (Moraceae) in Taiwan. Q J Forest Res 2009, 31: 33–46.

Tzeng H-Y, Ou C-H, Lu F-Y, Bain A, Chou L-S, Kjellberg F: The effect of fig wall thickness in Ficus erecta var. beecheyana on parasitism. Acta Oecologica 2014, 57: 38–43.

Ulenberg SA: The phylogeny of the genus Apocrypta Coquerel in relation to its hosts Ceratosolen Mayr (Agaonidae) and Ficus L. V K Ned Akad W, A Nat, Tweed Reeks 1985, 83: 149–176.

Wang H-Y, Hsieh C-H, Huang C-G, Kong S-W, Chang H-C, Lee H-H, et al.: Genetic and physiological data suggest demographic and adaptive responses in complex interactions between populations of figs ( Ficus pumila ) and their pollinating wasps ( Wiebesia pumilae ). Mol Ecol 2013, 22: 3814–3832.

Waterston J: On some Bornean fig-insects (Agaonidae - Hymenoptera Chalcidoidea). B Entomol Res 1921, 12: 35–40.

Weiblen G: How to be a fig wasp. Annu Rev Entomol 2002, 47: 299–330.

Weiblen GD, Flick B, Spencer H: Seed set and wasp predation in dioecious Ficus variegata from an Australian wet tropical forest. Biotropica 1995,27(3):391–394.

Westwood JO: Further descriptions of insects infesting figs. T Roy Entomol Soc London 1883,31(1):29–47.

Wiebes JT: Provisional host catalogue of fig wasps (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea). Zool Verh 1966, 83: 3–44.

Wiebes JT: Agaonid fig wasp from Ficus salicifolia Vahl and some related species of the genus Platyscapa Motschoulsky (Hym., Chalc.). Neth J Zool 1977, 27: 209–223.

Wiebes JT: The genus Odontofroggatia Ishii (Hymenoptera Chalcidoidea, Pteromalidae Epichrysomallinae). Zool Meded, Leiden 1980, 56: 1–6.

Wiebes JT: Agaonidae (Hymenoptera Chalcidoidea) and Ficus (Moraceae): fig wasps and their figs, X ( Wiebesia ). P K Ned Akad C Biol 1993, 96: 91–114.

Wiebes JT: The Indo-Australian Agaoninae (pollinators of figs). North-Holland, Amsterdam; 1994.

Wu H-F: The symbiosis between Ficus erecta Thumb var. beecheyana and Blastophaga nipponica at Yang-Ming Shan. Master Thesis. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 1996.

Wu Z, Raven PH, Hong D: Flora of China. Volume 5: Ulmaceae through Basellaceae. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, Beijing and St. Louis; 2003.

Yang H-W: Variation in the phenology and population interactions between Ficus microcarpa L. f. and its pollinating wasp, Eupristina verticillata. Master Thesis. National Taiwan University, Taipei; 2011.

Yang H-W, Tzeng H-Y, Chou L-S: Phenology and pollinating wasp dynamics of Ficus microcarpa L. f.: adaptation to seasonality. Bot Stud 2013,54(1):e11.

Yang H-W, Bain A, Garcia M, Chou L-S, Kjellberg F: Genetic influence on flowering pattern of Ficus microcarpa . Acta Oecologica 2014, 57: 117–123.

Yao J-C: Mutualism between Wiebesia pumilae (Hill) and Ficus pumila var. pumila L. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 1998.

Yokoyama J, Iwatsuki K: A faunal survey of fig-wasps (Chalcidoidea: Hymenoptera) distributed in Japan and their associations with figs ( Ficus : Moraceae). Entomol Sci 1998,1(1):37–46.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to Professor Cornelis C. Berg, who passed away in August, 2012. His research provided the deep foundations of the Ficus taxonomy. We acknowledge the ANR-NSC grant (ANR-09-BLAN-0392-CSD 7, NSC 99-2923-B-002-001-MY3) for providing funding for this work. We are very grateful to the permission on collecting fig samples issued by the Hengchun Research Center of Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, the National Parks in Kenting and Yangmingshan. For assistance with identifying and naming fig wasps, we are deeply grateful to J-Y Rasplus and F Kjellberg. We also thank H-W Yang, M Peng and Y-P Chiang for help uncovering the rich Taiwan fig literature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AB carried the writing of the early draft and the gathering of the fig wasp bibliography. THY, WWJ and CLS verified all the data and conceived the final version of the review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bain, A., Tzeng, HY., Wu, WJ. et al. Ficus (Moraceae) and fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) in Taiwan. Bot Stud 56, 11 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-015-0090-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-015-0090-x