Abstract

Background

Aeromagnetic data of the Ikogosi warm spring region was used to calculate the basal depth of the magnetic layer (Curie point depth) in the region. The warm spring issues from a crossing of fractures from a metasedimentary suite of Effon Psammite formation which form part of the Precambrian basement complex in Nigeria.

Method

The adopted computational method transforms the spatial data into the frequency domain and provides a relationship between radially average power spectrum of the magnetic anomalies and the depths to the respective sources. Heat flow density and equivalent depth extent of heat production from radioactive isotopes in the area were also evaluated.

Results

The average Curie point depth for the Ikogosi warm spring area is 15.1 ± 0.6 km and centres on the host quartzite rock unit. The computed equivalent depth extent of heat production provides a depth value (14.5 km) which falls within the Curie point depth margin and could indicate change in mineralogy. The low Curie point depth observed at the warm spring source is attributed to magmatic intrusions at depth. This is also evident from the visible older granite intrusion at Ikere - Ado-Ekiti area, with shallow Curie depths (12.37 ± 0.73 km).

Conclusions

Results indicate that the area is promising for further geothermal explorations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

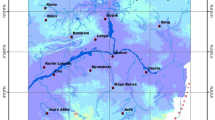

The Ikogosi Warm Spring is located in the southwestern part of Ekiti State of Nigeria. It is situated between lofty steep-sided and heavily wooded, north-south trending hills about 17 miles (approximately 27.4 km) east of Ilesha, and about 6.5 miles (approximately 10.4 km) southeast of Effon Alaye (Rogers et al. [1969]). It lies on the geographic latitude of 7°35′N and longitude 5°00′E (Figure 1) within the central region of the area covered by this study. Located within the Precambrian basement complex of southwestern Nigeria, it is at an altitude of 450 to 500 m (Adegbuyi and Abimbola [1997]).

Location of Ikogosi Warm Spring in the basement complex of Nigeria (after Adegbuyi and Abimbola[1997]). The dominant geology of Nigeria made mainly by crystalline (Precambrian basement complex) and sedimentary rocks (Cretaceous recent sediments) are also represented. The map also shows the locations of seismicity (modified from Eze et al. [2011]). The Ibadan and Ijebu Ode locations of seismicity appear closest to the study area.

The area covered by this study lies approximately between geographic latitudes 7°00′N and 8°00′N and geographic longitude 4°30′E and 5°30′E within the Precambrian of southwestern Nigeria. The area is covered by the aeromagnetic map sheet 243 (Ilesha), 244 (Ado-Ekiti), 263 (Ondo) and 264 (Akure) spanning an area of approximately 12,400 km2. Adegbuyi and Abimbola ([1997]) performed an extensive research on the energy resource potential of the Ikogosi Warm Spring area using the technique of Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA). They investigated the radiochemical contents of uranium (U), thorium (Th) and potassium (K) in a surface rock collection from the area and predicted the source of the warm spring’s heat to be radioactive probably acquired by meteoric water at depth from thorium-bearing zones of the quartzite host rock of the spring. Samples of the warm spring water and host quartzite rock collected from Ikogosi area were analysed for the fluid physio-chemical characteristics and rock radioactivity in a bid to predict the source of water and the associated heat content (Rogers et al. [1969]; Loehnert [1985]; Adegbuyi et al. [1996]). The results were almost similar with predictions made about radioactivity and high geothermal gradient responsible for the heat of the Ikogosi Warm Spring. Joshua and Alabi ([2012]) investigated the pattern of radiogenic heat production in rock samples of southwestern Nigeria while Oladipo et al. ([2005]) carried out hydrochemical analysis on water samples from the Ikogosi Warm Spring in southwestern Nigeria. Earlier studies of the warm spring have been restricted to geological and geochemical investigations (Rogers et al. [1969]; Loehnert [1985], Adegbuyi et al. [1996]; Ajayi et al. [1996]). Ojo et al. ([2011]) carried out an investigation of the geological structure beneath the Ikogosi Warm Spring in southwestern Nigeria using integrated surface geophysical methods. They integrated vertical electrical sounding (VES) and magnetic methods in the immediate vicinity of the Ikogosi Warm Spring with a view to delineate its subsurface geological sequence and evaluate the structural setting beneath the warm spring. They used inverse magnetic models and geoelectrical sections to delineate fractured quartzite/faulted areas within fresh massive quartzite at varying depths. It was deduced that the fractured/faulted quartzite may have acted as conduit for the movement of warm groundwater from profound depths to the surface while the spring outlet was located on a geological interface (lineament).

The present study attempts to determine the depths to the top and bottom of the magnetized crust and to characterize the heat flow within the Ikogosi Warm Spring area using Curie point depth (CPD) estimates from spectral analysis of aeromagnetic data. Results will be invaluable to electricity generation companies in Nigeria, especially now that alternative sources of power generation in Nigeria are being explored. The CPD is known as the depth at which the dominant magnetic mineral in the crust passes from a ferromagnetic state to a paramagnetic state under the effect of increasing temperature (Nagata [1961]). For this purpose, the basal depth (depth to the bottom) of a magnetic source from aeromagnetic data is considered to be the CPD (Dolmaz et al. [2005]).

Geological setting

About two thirds of Nigeria’s landmass is underlain by the Precambrian basement complex (Figure 1). The crystalline rocks in Nigeria are made up of the Precambrian basement complex and the Phanerozoic rocks. These crystalline basement rocks have been subjected to deformation of different intensities throughout the geological period. Consequently, NS, NE-SW, NW-SE, NNE-SSW, NNW-SSE and to a less extent, E-W fractures have developed (Olujide and Udoh [1989]; Eze et al. [2011]). The Precambrian basement rocks consist of the migmatite-gneissic-quartzite complex dated Archean to early Proterozoic (2,700 to 2,000 Ma). Other units include the NE-SW trending schist belts mostly developed in the western half of the country and the granitoid plutons of the Older Granite suite dated Late Proterozoic to early Phanerozoic (750 to 450 Ma). The main lithologies of the southwestern (SW) Nigeria basement complex includes the amphibolites, migmatite gneisses, granites and pegmatites. Others are the schist made up of biotite, quartzite, talk-tremolite and the muscovite. Crystalline rocks intruded into these schistose rocks (Oyinloye [2011]). The basement complex is in places intruded and interspersed also by the older granites which originated in the Pan-African orogeny. Basement complex rocks in Nigeria have been subjected to deformation of different intensities throughout the geological period. Consequently, fractures have developed.

The warm spring issues with a temperature of 38°C near the foot of the eastern slope of the north-south trending ridge from a thin quartzite unit within a belt of quartzite which includes quartz-mica schist and granulitic migmatite east of Ilesha (Figure 2). The Okemesi quartzite member is characterized by a North-South trending ridge called the Effon ridge (Elueze [1988]; Oyinloye [1992]). The quartzitic rocks are composed of dominant quartz with muscovite, chlorite and sericite occurring in minor proportions (Adegbuyi and Abimbola [1997]). Rogers et al. ([1969]) suggested that the source of springs in the Effon Psammite formation is associated with a faulted and fractured quartzite band sandwiched between schists. Chemical data show that quartzite is largely metamorphosed sandstones containing minor arkosic intercalations (Olade and Elueze [1979]; Elueze [1988]). On the basis of petrology, a medium pressure Barrovian and low medium pressure types of metamorphism had been suggested for the Precambrian basement rocks in southwestern Nigeria (Oyinloye [2011]). Chuku-Ike and Norman ([1977]) and Mbonu ([1990]) believe that the intersections of the NNE-SSW epeirogenic belts with the NW-SE fracture trends in Nigeria coincide with the centres of warm springs like the Wikki (Bauchi State) and Ikogosi (Ekiti State) springs. The issue of the springs is controlled by permeability developed within the quartzite as a result of intergranular pore spaces coupled with fracturing of the relatively competent quartzite (Rogers et al. [1969]).

Nigeria is not situated on any known seismic belt, yet between 1933 and 2000, Nigeria experienced fifteen seismic events, three of which occurred in 1 year (Figure 1). The intensities of these events ranged from III to VI based on the modified Mercalli Intensity Scale. Three of the events, the 1984 seismicity at Ijebu Ode, the 1990 at Ibadan and 2000 at Jushi-Kwari were instrumentally recorded. They had body wave magnitudes ranging from 4.3 to 4.5, local magnitudes between 3.7 and 4.2, and surface wave magnitudes of 3.7 to 3.9 (Ajakaiye et al. [1987]; Akpan and Yakubu [2010]; Eze et al. [2011]). Two of them (Ibadan and Ijebu Ode measurements) are located close to our study area (the Ikogosi Warm Spring area). Some of the important fault systems in Nigeria are the Ifewara, Zungeru, Anka and Kalangai fault systems. They are interpreted to have resulted from transcurrent movements (Garba [2003]; Eze et al. [2011]). Of these, only the Ifewara fault is located in the region of this study. Adepelumia et al. ([2008]) confirmed the existence of Ifewara shear zone formed by sharing activities during Late Precambrian times using multi-spectral scanner (MSS) and side-looking airborne radar (SLAR) images. They identified a NNE-SSW trending Ifewara fault system in the area and showed that the 250 km-long NE-SW trending Ifewara fault zone could be linked with Atlantic fracture system. Burke et al. ([1977]) and Hubbard ([1975]) believed that the pronounced age difference on both sides of the fault zone suggests that the zone may indeed be a suture of Kibaran age. Burke ([1969]) suggested possible relationship between the epicentres of some of the West African earthquakes and continentward extensions of oceanic fractures into the landmass. Stresses built up around plate boundaries could travel toward the centre of the plate triggering intraplate seismicity especially in pre-existing faults. The coastal area of Nigeria lies in close proximity to the boundary between the African plate and South American plate. Some of the seismic activities that occurred in the coastal areas of Nigeria have been possibly initiated by this process (Eze et al. [2011]).

Methods

Regional magnetic feature and geology

A high-resolution aeromagnetic survey over the Ikogosi Warm Spring and its surroundings was conducted between 2004 and 2008 and published by the Geological Survey of Nigeria (GSN) on a map scale of 1:100,000 series. The various map sheets obtained were processed and merged together to a common dataset. They were transformed to a total field anomaly dataset and gridded at 0.5 km. The analysis of magnetic field used reduced to the pole data (RTP). The RTP correction applied assumed a declination of −3° and an inclination of −10° for this region utilizing the method of Silva ([1986]). Figure 3 shows the geomagnetic anomaly field map of the study area. The map had the regional geomagnetic field and the effects of diurnal magnetic variations removed.

Geomagnetic anomaly field map of the study area. The data was reduced to the pole assuming a declination of −3° and an inclination of −10° for this region. Notable (positive) anomalies are observed at the Oshogbo, Okemesi and Ilesha locations reaching values of 60 to 112 nT. Positive anomalies of 50 to 70 nT are also observed at the Ijero-Ekiti and within the towns of Ado-Ekiti. Negative magnetic anomalies ranging from −30 to −156 nT have been noted in the towns of Erinmo, Ifewara, Oriade, Ikogosi and Okeigbo.

The magnetic map and geologic map shows a good correlation between exposed geologic units and magnetic signatures. The strong variations in magnetic intensity suggest a wide variety of different magnetic properties. Notable (positive) anomalies are observed at the Oshogbo, Okemesi and Ilesha locations (Figure 3) reaching values of 60 to 112 nT. This tends to correspond with the exposed undifferentiated metasediments noted in these locations (Figure 2). Positive anomalies of 50 to 70 nT are also observed at the Ijero-Ekiti location whose probable source could be traced to the undifferentiated metasediments in this region. Within the towns of Ado-Ekiti and Ikere, positive magnetic anomalies of 80 to 110 nT were obtained. We traced this observation to the Older Granites domiciled in this region. In other regions of the map encompassing the towns of Erinmo, Ifewara, Oriade, Ikogosi and Okeigbo, negative magnetic anomalies ranging from −30 to −156 nT have been noted. The belt of quartzite, quartz-mica schist and granulitic migmatite encapsulated by the quartzite belt in the region is identified with this observation. This quartzite is part of the Okemesi quartzite member of the Effon Psammite formation (east of Ilesha) belonging to the Ife-Ilesha schist belt of the Precambrian basement complex of Nigeria (Loehnert [1985]; Adegbuyi et al. [1996]). The Ikogosi town (study location) has magnetic lows of −0.46 to −35 nT, extending westwards. This location is also part of the fractured quartzite unit in the formation.

One of the methods of examining thermal structure of the crust is the estimation of the CPD, using aeromagnetic data (Dolmaz et al. [2005]). Various studies have shown correlations between Curie temperature depths and average crustal temperatures, leading to viable conclusions regarding lithospheric thermal conditions in a number of regions around the world (Ross et al. [2006]). The mathematical model on which our analysis is based is a collection of random samples from a uniform distribution of rectangular prisms, each prism having a constant magnetization. Two fundamental methods serve as a basis of all subsequent analysis, first provided by Spector and Grant ([1970]), estimating the average depths to the top of the magnetized bodies from the slope of the log power spectrum and second by Bhattacharyya and Leu ([1975]) for obtaining the depth to the centroid of the causative body. The method can provide valuable information about the regional temperature distribution at depths not easily examined using other methods (Okubo et al. [1985]). The Curie temperature isotherm corresponds to the temperature at which magnetic minerals lose their ferromagnetism (approximately 580°C for magnetite at atmospheric pressure). Magnetic minerals warmer than their Curie temperature are paramagnetic and from the perspective of the earth’s surface are essentially nonmagnetic (Ross et al. [2006]). Thus the Curie temperature isotherm corresponds to the basal surface of magnetic crust and can be calculated from the lowest wavenumbers of magnetic anomalies, after removing the approximate regional field from the aeromagnetic data (e.g. Bhattacharyya and Morley [1965]; Spector and Grant [1970]; Mishra and Naidu [1974]; Byerly and Stolt [1977]; Connard et al. [1983]; Hamdy et al. [1984]; Blakely [1988]; Tanaka et al. [1999]; Salem et al. [2000]; Ross et al. [2006]).

We applied the methods of Spector and Grant ([1970]), Okubo et al. ([1985]) and Trifonova et al. ([2006]), which examined the spectral knowledge included in subregions of magnetic data for our analysis.

Spectral analysis

The earliest papers on Curie point depth determination based on spectral analysis of geomagnetic data are those of Byerly and Stolt ([1977]) where analyses for different areas of USA have been published. More recently, investigations have been made for parts of the territory of Japan (by Okubo [1985, 1989, 1994]), USA (by Mayhew [1985]; Blakely [1988]), Greece (Tsokas et al. [1998]; Stampolidis and Tsokas [2002]), Portugal (Okubo et al. [2003]), Bulgaria (Trifonova et al. [2006, 2009]) and Turkey (Dolmaz et al. [2005]; Maden [2009]). Authors consider the power spectrum of the total geomagnetic field intensity anomaly over a single rectangular block using the expression, which was first given by Bhattacharyya ([1965]). The equation was transformed into polar wavenumber coordinates (S,ψ), and the average depths to the top of magnetized bodies from the slope of the log power spectrum were calculated. The model has proven successful in estimating average depths to the tops of magnetized bodies (Trifonova et al. [2006]).

One principal result of Spector and Grant’s analysis is that the expectation value of the spectrum for the model is the same as that of a single body with the average parameters for the collection (Okubo et al. [1985]).

In polar coordinates (S,ψ) in frequency space, this spectrum has the form

where J = magnetization per unit volume; A = average cross-sectional areas of the bodies; L, M, N = direction cosines of the geomagnetic field; l, m, n = direction cosines of the average magnetization vector; a and b = average body x- and y-directions, xo and yo = average body x- and y-centre locations and zt and zb = average depths to the top and bottom of the bodies, and where

Following Bhattacharyya and Leu ([1975, 1977]), estimation of the bottom depths could be approached in two steps: first, find the centroid depth zo and second, determine the depth to the top zt. The depth to the bottom (inferred CPD) is calculated from these values:

The terms involving zt and zb can be recast into a hyperbolic sine function of zt and zb plus a centroid term. At very long wavelengths, the hyperbolic sine tends to unity, leaving a single term containing zo, the centroid. At somewhat shorter wavelengths, the signal from the top dominates the spectrum and an estimate of the depth to the top can be obtained (Okubo et al. [1985]). If we begin with the centroid, at very long wavelengths (compared to the body dimensions), the terms involving the body parameters (a, b, and zb-zt) may be approximated by their leading terms, to yield

where V is the average body volume.

Equation 3 can be recognized as the spectrum of a dipole.

In effect, the ensemble average at these very low frequencies is that of a random distribution of point dipoles. What follows, therefore, is independent of the details of the body parameters (prisms, cylinders or whatever), provided that the dimensions in all directions are comparable. The method of Okubo et al. ([1985]) was used in estimating zo from Equation 3:

If

First, average the square amplitude of G over an angle in the frequency plane

Then H(s) has the form

if F satisfies Equation 3, where A is a constant. Hence,

holds. The centroid depth zo can now be estimated by least-squares fitting ln H(s) with a constant and a term linear in s.

The second step is the process of estimating the depth to the top. For this purpose, we return to Equation (1) and assume that a range of wavelengths can be found for which the following approximations hold:

and

For these approximations to make sense, the bodies must in general be large in depth compared to their horizontal dimensions. However, if the distribution of horizontal body dimension is very broad, a similar effect will be produced by variability in terms corresponding to the horizontal body dimensions.

If the above approximation holds, the spectrum reduces to the form

which is very similar to Equation 3, except for a factor of s. Equation 6 is in fact the spectrum of a monopole.

Estimation of zt is therefore done using

from which

follows, where B is a sum of constants independent of s,

then from

and fit ln K (s) with a constant and a term linear in s.

The reliability of this method has been proven in many cases (e.g. Okubo [1994]; Tsokas et al. [1998]; Trifonova et al. [2006]). Fast Fourier transform (FFT) estimates Fourier components between zero frequency and the Nyquist limit imposed by the grid cell size. The Nyquist frequency is the highest frequency (short wavelength) that is possible to measure given a fixed sample interval (Yawsangratt [2002]). It is defined by the expression (Clement [1972]; Billing and Rechards [2000]),

where ∆x is the sampling interval.

The sampling interval used during the analysis of data in this work, 500 m (0.50 km), directly imposes a Nyquist frequency of 1 km on the data.

Conductive heat flow

The basic relation for conductive heat transport is Fourier’s law (Tanaka et al. [1999]). In one-dimensional case under the assumptions that the direction of the temperature variation is vertical and the temperature gradient is constant, Fourier’s law takes the form

where q is the heat flux and k is the coefficient of thermal conductivity.

According to Tanaka et al. ([1999]), the Curie temperature (θ) can be obtained from the Curie point depth zb and the thermal gradient using the following equation:

In this equation, it is assumed that the is constant.

Tanaka et al. ([1999]) showed that any given depth to a thermal isotherm is inversely proportional to heat flow, where q is the heat flow. This equation implies that regions of high heat flow are associated with shallower isotherms, whereas regions of lower heat flow are associated with deeper isotherms (Ross et al. [2006]). An average surface heat flow value was computed using Equations 10 and 11 and was based on possible Curie point temperature of 580°C using a thermal conductivity of 2.5 Wm−1°C−1, given by Stacey ([1977]) as the average for igneous rocks.

Radiogenic heat generation

The presence of thorium-rich accessory minerals, such as monazite, zircon and rutile is usually linked to micaceous zones in radio-active porphyritic and coarse granite (Ragland and Roger [1961]; Gerard and Kappelymeyer [1987]). Such granitic rock bodies are found to be suitable nuclear resources including the uraniferous sandstone and marginal marine sediments. Using the scanning electron microscope to determine the spot chemical composition and empirical formulae of nearly all rock-forming minerals in the rocks of the basement complex of southwestern Nigeria, Oyinloye ([2011]) discovered the mineral, monazite. He concluded that this mineral was present as a notable accessory mineral in all the crystalline rocks of the basement complex in Ilesha area even in the amphibolites which is supposed to be igneous. Monazite is a phosphate of the rare earth elements, especially the light ones. The petrogenetic implication of the presence of monazite in the crystalline rocks of southwestern Nigeria is that the initial magma from which the precursor rocks were formed contains some input from the crustal or sedimentary source. There is therefore the possibility of a uranium/thorium bearing unit at a vertical depth in the micaceous-quartzite rock unit of the Ikogosi Warm Spring area (Adegbuyi and Abimbola [1997]). The majority of the continental heat flow originates from the decay of radioactive isotopes in the crust, thus finding areas with high isotope concentration can be equal to finding areas with high heat flow (Holmberg et al. [2012]).

Radiogenic heat production (RHP), H (μW/m3) is related to the decay of primarily, the radioactive isotopes 232Th, 238U and 40K and can be estimated based on the concentration (C) of the respective elements (Rybach [1988]; Holmberg et al. [2012]) through Equation 13:

where ρ is the density of the rock and its concentrations in uranium (Cu), thorium (CTh) are given in weight/parts per million and weight percent for potassium (CK).

Heat flow depends critically on radioactive heat production in the crust. The two primary effects are thus that continental heat flow is proportional to the surface crustal radioactivity in a given region and decreases with time since last major tectonic event (Stein [1995]). Heat flow must be a continuous function inside the earth; in particular, it will be the same on both sides of the boundary separating the crust from the mantle (Masters and Constable [2013]). A plot of heat flow and heat production rate from radioactivity of rocks revealed a linear distribution which can be fitted with a linear equation of the form:

where qs is the surface heat flow and qm is the mantle heat flow (heat flow into the base of the crust). The total contribution of heat production in the crust to the surface heat flow qr is therefore,

where ρ is density of the crust, Hs is the heat production measured in rocks collected at the surface, zr could be interpreted as the ‘equivalent depth extent of heat production’, that is, the extent to which the heat production measured at the surface (Hs) extends to depth if we consider distribution models for radioactivity in the crust and extent of heat production (Stuwe [2008]). Masters and Constable ([2013]) had assumed that zr is much less than the thickness of the continental crust. Clearly, in nature, radioactivity is not constant in the crust down to zr and zero below that, but this model gives us a fair indication of the proportion of surface heat flow that is due to radioactivity (Stuwe [2008]).

Results

Map division into overlapping subregions

In the estimation of depths to the Curie temperature in Oregon, for example, Connard et al. ([1983]) divided a magnetic survey into overlapping cells (77 × 77 km) and calculated for each cell a radially average power spectrum. However, the spectrum of the map only contains depth information to a depth of length (L)/2π (Shuey et al. [1977]). If the source bodies have bases deeper than L/2π, the spectral peak occurs at frequency lower than the fundamental frequency for the map and cannot be resolved by spectral analysis (Salem et al. [2000]).

Our method has evolved from published methods. Rather than dividing the aeromagnetic data into overlapping subregions of equal dimension on a uniform grid, we selected subregions of dimension 55 × 55 km across the entire magnetic map and additional random blocks at prominent magnetic anomaly regions. We ensured at least 50% overlap of the blocks and our choice of 55 × 55 km dimension was adopted from the size of each of the four map sheets incorporated for the total field intensity map. The number of overlapping blocks of 22 was discretionary, guided by the concentration of prominent magnetic anomalies on the map. The coordinates at the centre of each block, representing the sampled point, were noted for the CPD location. We adopted the current method to enable sampling of more data points. Given the location of the Ikogosi Warm Spring (7°35′N, 5°00′E) at the centre of the aeromagnetic map investigated, our method enabled adequate probing of the warm spring area. Figure 4 shows the sampled points for the CPD analysis realized from our method.

For simplification of the approach used in our CPD analysis (Bhatacharyya and Leu [1975, 1977]; Okubo et al. [1985]), we resolve these steps to Equation 16 for deriving the depth to the centroid (zo) and Equation 17 for estimation of the depth to the top boundary (zt) of that distribution:

where P(s) is the radially averaged power spectrum of the anomaly, |s| is the wavenumber, A is a constant and B is a sum of constants independent of |s|. Then the basal depth (zb) of the magnetic source is calculated from Equation 2. The obtained basal depth of a magnetic source is assumed to be the CPD. FFT was used to convert the space domain grid data to the Fourier domain. The radially average log power spectrum of each block was computed using MAGMAP filtering program (GEOSOFT MAGMAP [2007]). The radially averaged energy represents the spectral density (energy) averaged for all grid elements at the wavenumber. Figure 5 shows the example of the radially averaged power spectrum plot for block 5 of the 22 blocks. From the centroid depth of 7.60 ± 0.06 km and depth to the top of 0.78 ± 0.02 km, CPD is calculated as 14.42 ± 0.53 km with percentage uncertainty at 3.7 for this block. The 22 estimated CPD values of the study area range from 11.5 to 21.9 km. Table 1 and Figure 6 shows the CPD values and CPD map of the study area, respectively.

Example of radially average power spectrum for estimation of the CPD using the two-dimensional magnetic anomaly data of Block 5. Depths of 7.60 and 0.78 km are obtained as the centroid and top bound using the gradient of spectra defined as ln (P1/2/|s|) and ln (P1/2), where |s| is the wavenumber and P(s) is the radially average power spectrum.

Considering Equation 14 and supposing we take a uniform distribution of heat-producing elements and use a value for H typical of granite (H = 9.6 × 10− 10Wkg− 1) (Fowler [2005]; Masters and Constable [2013]), the contribution to qs from heat-producing elements in the crust is qm = ρ Hz = 91 mWm− 2, using ρ = 2, 700 kg m− 3 and z = 35 km (assumed depth of crust):

The negative sign indicates that z is pointing in the opposite direction of q (Masters and Constable [2013]). From Equations 14 and 15, we have

In the terrestrial continental crust, the average heat flow is between 65 mW/m2 and 48 mW/m2. For our calculations, we assumed a surface heat flow value of 65 mW/m2 for continental lithosphere (Pollack et al. [1993]). We adopted the concentrations of U, Th and K in surface rocks collected from the Ikogosi Warm Spring region, given in average concentration values of 6.68 ppm U, 27.19 ppm Th and 5.77% K for both quartzite and schistose rock types (Adegbuyi and Abimbola [1997]). Equation 13 was applied in Equation 19 with the average density of quartzite taken as 2650 kgm− 3 (Marciniszyn et al. [2013]).

Discussion

According to Ross et al. ([2006]), in places where heat flow information is inadequate, the depth to the Curie temperature isotherm may provide a proxy for temperature-at-depth. The map in Figure 6 shows the CPD for the Ikogosi Warm Spring area, determined by applying a minimum curvature algorithm to the CPD values in Table 1. To quantify the error in the estimated CPD, we evaluated the standard and statistical errors of the power density spectrum from the linear fit using the definition of the error adopted from Trifonova et al. ([2009]) and Okubo and Matsunaga ([1994]). The results of the spectral analysis of aeromagnetic anomalies over the Ikogosi Warm Spring area show Curie point depth minimum estimates range between 11.5 ± 1.6 and maximum estimates 21.9 ± 1.7 km (Table 1) with an average value of 15.1 ± 0.6 km. Studies have shown that the Curie point depth is linked to the geological context. Tanaka et al. ([1999]) pointed out that the Curie point depths are shallower than about 10 km at volcanic and geothermal areas, 15 to 25 km at island arcs and ridges, deeper than 20 km at plateaus and deeper than 30 km at trenches. The warm spring presence in the study area qualifies the area for the second description. Loehnert ([1985]) and Adegbuyi et al. ([1996]) had submitted that the warm spring issues with temperature range of 37°C to 38.5°C near the foot of the eastern slope of a north-south trending ridge from a thin quartzite unit within a belt of quartzite.

In particular, depths to the base of magnetic crust determined from subregions centred over the Ikogosi Warm Spring area are generally shallower than those determined for areas farther from the warm spring source. Shallow CPD values are also noted farther from the spring source and within the Ikere, Ado-Ekiti and east of Akure. These regions do not fall within the highly fractured quartzite belt stretching in the NNE-SSW direction (Figure 2), considered an aquifer system with relatively high storage capacity (Loehnert [1985]); hence, the lack of physical heat signatures as compared with the Ikogosi Warm Spring area where the aquifer system along with faults and shallow CPDs results in the warm spring. In addition to this observation, the shallow Curie depth observed could be a result of the intruded Older Granite unit spotted in that region. This peculiar observation led us to assert that the low CPD at the spring source location could also be due to magmatic intrusion at depth in the highly fractured quartzite unit. Olujide and Udoh ([1989]) had asserted that the basement complex of Nigeria is in places intruded and interspersed by older granites which originated in the Pan-African orogeny. Generally, at depths of 100 to 200 m, normal increase in temperature with depth (geothermal gradient of 35°C km−1 for crystalline non-seismic terrains of the world) cannot sufficiently explain the rather small temperature difference (about 12°C) between the adjacent warm and cold springs of the Ikogosi area (Adegbuyi and Abimbola [1997]). The sharp increase of CPD away from the warm spring source location (Figure 6) provides a fair satisfactory explanation. We conclude that the source of the warm spring sits on a very shallow CPD in sharp contrast to the cold spring (a tributary of the Owena River, Rogers et al. [1969]) source which confluences with the warm spring.

Curie temperature depends on magnetic mineralogy (Tanaka et al. [1999]). We agree with the conclusions of Schlinger ([1985]) and Frost and Shive ([1986]) that magnetite is the dominant magnetic mineral contributing to the long wavelength magnetic anomalies in the continental crust; hence, 580°C is a reasonable Curie temperature for deep crustal rocks (Ross et al. [2006]). We have been constrained by lack of data on temperature measurements at depth in the region of study and indeed the entire crystalline basement complex of Nigeria. The closest temperature gradient measurement was done by Verheijen and Ajakaiye ([1979]). This was conducted in available boreholes located in the centre of the Nigerian Ririwai complex (being one of the granitic ring structures of younger granites province of northern Nigeria, located within the Precambrian shield) which gave a heat flow of 0.92 ± 0.04 hfu (38.5 ± 1.7 mW/m2). The result is of the same order of magnitude as what should be expected in the surrounding Precambrian basement complex at about 0.9 ± 1.2 hfu (37.6 ± 50.2 mW/m2) if the worldwide averages given by Lee and Uyeda ([1965]) and Kappelmeyer and Haenl ([1974]) are assumed to be correct (Verheijen and Ajakaiye [1979]). Obviously, no far-reaching conclusions can be drawn from a few measurements, and there is need to have measurements made in a series of boreholes located at adequate intervals within the basement complex. On the basis of insufficient temperature measurements in depth, we calculated the average heat flow from our study assuming a constant Curie temperature of 580°C and compare with the measured heat flow value from Verheijen and Ajakaiye ([1979]) and the worldwide averages for Precambrian basement complex. While our average heat flow of 91.2 ± 2.1 mW/m2 shows significant departure from Verheijen and Ajakaiye ([1979]) value for the northern Nigeria crystalline complex, it however tends to agree with the worldwide averages’ value for Precambrian basement complex. The average heat flow in thermally ‘normal’ continental region is about 65 mW/m2 (Pollack et al. [1993]). Values in excess of about 80 to 100 mW/m2 indicate anomalous geothermal condition in the subsurface (Sharma [2004]). The presence of the Ikogosi Warm Spring in the region of study and the estimated average heat flow value obtained under our assumptions indicates anomalous geothermal condition in the subsurface.

The combined determinations of heat flow density and of radioactive heat production rate yield basic information about the temperature field and the structure of the earth’s crust and are indispensable to understand the interrelations between heat flow density and geology (Abbady et al. [2004]). Due to the absence of deep boreholes data for heat flow measurements within the study area, surface measurements have been used as the information source. Our calculations of RHP in the study area shows an average value of 4.06 μWm− 2. This value appears to be relatively higher when compared to the average heat production of the Precambrian shield, 0.77 ± 0.08 μWm− 3 given by Jaupart and Mareschal ([2003]), although they also stress that on a local scale, the variation from their value could be significant. We attribute the significant increase in our radiogenic heat flow value to the high radioelement contents (Adegbuyi and Abimbola [1997]) obtained for the dominant quartzite rocks in the region. Regardless how the heat flux data are selected, there is absolutely no correlation between heat flux and crustal thickness. If the heat flux and the total crustal heat production do not increase with crustal thickness, the concentration in heat-producing elements must decrease as the thickness of the crust increases (Mareschal and Jaupart [2013]). Recall that radioactivity is not constant in the crust down to the equivalent depth extent of heat production and zero below that (Stuwe [2008]). We calculate our equivalent depth extent of heat production (Equation 19) to obtain a value of 14.5 km and compare with the average CPD value of 15.1 ± 0.6 km obtained for the region. We observed that our equivalent depth extent of heat production lies within the CPD margin. Pollack and Chapman ([1977]) showed that RHP contributes about 45% of the surface heat flow observed over the continents, while Lachenbruch ([1970]), Swanberg ([1972]) and Lowrie ([1997]) showed that its magnitude exponentially decreases with depth. This decay indicates that RHP comes from a superficial layer of the crust, 4 to 16 km (Okeyode [2012]). Therefore, our calculated CPD could as well be a representation of the depth of total decrease of heat-producing elements or change in mineralogy in the crust.

The sources of seismicity in Nigeria include inhomogeneities and zones of weakness in the crust created by the various episodes of magmatic intrusions and other tectonic activities (Eze et al. [2011]). The possible mechanism for Nigeria’s seismicity have been attributed to the locations of earth movements associated with NE-SW trending fracture and zones of weakness extending from the Atlantic Ocean into the country (Ajakaiye et al. [1986], Ajakaiye et al. [1987], Eze et al. [2011]). We observe a concentration of seismic activity points close to the study region in the Ijebu ode and Ibadan locations (Figure 1). Adepelumia et al. ([2008]) identified a NNE-SSW trending Ifewara fault system (Figure 2) in the area and showed that the 250-km-long NE-SW trending Ifewara fault zone could be linked with Atlantic fracture system. Considering that in volcanically active regions around the world earthquake swarms associated with contemporaneous crustal deformation are often inferred to be the result of subsurface magma movements (Wright et al. [1976]), we propose that the seismic activities could be as a result of movement of, or within, magmatic intrusions in this zone which could also contribute to the low CPD obtained at the Ikogosi Warm Spring region. A thick magnetic crust suggests stable continental regions while thin magnetic crust accounts for tectonically active regions also associated with higher heat flow (Rajaram et al. [2009]).

Conclusions

We have applied spectral analysis to aeromagnetic anomalies in order to estimate the basal depth herein assumed Curie point depth, beneath the Ikogosi Warm Spring region - Ekiti State, Nigeria. We found out that the region is characterized by shallow Curie depths and high heat flow. The Ikogosi Warm Spring area is underlined by an average Curie point depth of 15.1 ± 0.6 km. This shallow CPD implies a heat flow of 91.2 ± 2.1 mW/m2. We were however constrained by the lack of additional information about temperature measurements at depth so we compare our calculated heat flow result with the value expected in Precambrian basement complex. We observed that our value lies within the margins of the expected value of 37.6 ± 50.2 mW/m2 (Verheijen and Ajakaiye [1979]) and conclude that our calculations seem satisfactory. We also consider the relationship between heat flow density and radioactive heat production rate to further confirm our CPD results. Our estimated equivalent depth extent of heat flow density and radioactive heat production also falls within the margins of the CPD values for the region, despite that they were computed independent of each other. We conclude that the equivalent depth extent in this respect could represent the depth of change in mineralogy in the crust. Generally, we conclude that the shallow CPD observed is due to magmatic intrusion at depth. The seismic activities recorded close to this region, a major fault presence (Ifewara fault), multiple fractures in the rock units and low CPDs could be results of movement of, or within, thin magmatic intrusions. We therefore recommend detailed temperature measurement at various depths through a series of boreholes to be located at adequate intervals within the crystalline basement complex of Nigeria. This would provide the much needed data for further studies of the origin, emplacement, geophysical and geological characteristics of the basement complex. The results obtained in this work have provided important geophysical/geological inputs which are useful to further geothermal energy exploration in the region.

References

Abbady AGE, Arabi AME, Abbady A (2004) Heat production rate from radioactive elements in igneous and metamorphic rocks in eastern desert, Egypt. In: Proceedings of the Seventh Radiation Physics and Protection Conference (RPC-2004), Ismaila, Egypt, pp 287–294

Adegbuyi O, Abimbola AF: Energy resource potential of Ikogosi Warm Spring Area, Ekiti State, Southwestern Nigeria. African J Sc. 1997, 1(2):111–117.

Adegbuyi O, Ajayi OS, Odeyemi IB: Prospect of a Hot Dry Rock (HDR) geothermal energy resource around the Ikogosi-Ekiti Warm Spring in Ondo State. Nigeria. N. J. Renewable Energy 1996, 4(1):58–64.

Adepelumia AA, Akoa BD, Ajayi TR, Olorunfemi AO, Falebitaa DE: Integrated geophysical mapping of the Ifewara transcurrent fault system. Nigeria. J. African Earth Sc. 2008, 52(4–5):161–166. 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2008.07.002

Ajakaiye DE, Hall DH, Millar TW, Veheijen PJ, Awad MB, Ojo SB: Aeromagnetic anomalies and tectonic trends in and around the Benue Trough, Nigeria. Nature 1986, 319: 582–584. 10.1038/319582a0

Ajakaiye DE, Daniyan MA, Ojo SB, Onuoha KM: Southwestern Nigeria earthquake and its implications for tectonics and evolution of Nigeria. J. Geodynamics 1987, 7: 205–214. 10.1016/0264-3707(87)90005-6

Ajayi OS, Adegbuyi O, Farai P, Ajayi IR: Determination of natural radionuclides in rocks of the Ikogosi Ekiti warm spring area, Ekiti State. Nigeria. Nigerian J. Sc. 1996, 30(2):15–21.

Akpan OU, Yakubu AY: Earthquake Science. 2010, 23: 289–294. 10.1007/s11589-010-0725-7

Bhattacharyya BK, Leu LK: Spectral analysis of gravity and magnetic anomalies due to two-dimensional structures. Geophysics. 1975, 40: 993–1013. 10.1190/1.1440593

Bhattacharyya BK, Leu LK: Spectral analysis of gravity and magnetic anomalies due to rectangular prismatic bodies. Geophysics 1977, 42: 41–50. 10.1190/1.1440712

Bhattacharyya BK, Morley LW: The delineation of deep crustal magnetic bodies from total field aeromagnetic anomalies. J Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity 1965, 17: 237–252. 10.5636/jgg.17.237

Billings S, Richards D: Quality control of gridded aeromagnetic data. Exploration Geophysics 2000, 31: 611–616. 10.1071/EG00611

Blakely RJ: Curie temperature analysis and tectonic implications of aeromagnetic data from Nevada. J. Geophys. Res. 1988, 93(B10):11817–11832. 10.1029/JB093iB10p11817

Burke K: Seismic areas of the Guinea Coast where the Atlantic fracture zones reach Africa. Nature 1969, 222(5194):655–657. 10.1038/222655b0

Burke K, Dewey J, Kidd WSF: World distribution of sutures - the sites of former oceans. Tectonophysics 1977, 40: 66–99. 10.1016/0040-1951(77)90030-0

Byerly PE, Stolt RH: An attempt to define the Curie-temperature isotherm in Northern and Central Arizona. Geophysics. 1977, 42: 1394–1400. 10.1190/1.1440800

Chuku-Ike IM, Norman JW: Mineral crustal show on satellite imagery of Nigeria. Trans. Int. Min. Met. 1977, 86: 855–857.

Clement WG (1972) Basic principles of two-dimensional digital filtering. Geophysical Prospecting: 125–145

Connard G, Couch R, Gemperle M: Analysis of aeromagnetic measurements from the Cascade Range in the Central Oregon. Geophysics 1983, 48: 376–390. 10.1190/1.1441476

Dolmaz MN, Ustaomer T, Hisarli ZM, Orbay N: Curie point depth variations to infer thermal structure of the crust at the African-Eurasian convergence zone, SW Turkey. Earth Planets Space 2005, 57: 373–383.

Elueze AA: Geology of the Precambrian schist belt in IIesha area, southwestern Nigeria. Precambrian geology of Nigeria. GSN 1988, 77–89.

Eze CL, Sunday VN, Ugwu SA, Uko ED, Ngah SA (2011) Mechanical model for Nigerian intraplate earth tremors., Earthzine. , [http://www.earthzine.org/2011/05/17/mechanical-model-for-nigerian-intraplate-earth-tremors/]

Fowler CMR: The solid earth: an introduction to global geophysics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 2005.

Frost BR, Shive PN: Magnetic mineralogy of lower magnetic crust. J. Geophys. Res. 1986, 91: 6513–6521. 10.1029/JB091iB06p06513

Garba I: Geochemical characteristics of mesothermal gold mineralisation in the Pan-African (600± 150 Ma) basement of Nigeria. Applied Earth Sc: IMM transactions section B 2003, 112(3):319–325. 10.1179/037174503225003143

Geosoft MAGMAP (2007) Oasis MontajTM 6.4.2 (HJ). Geosoft Inc, Toronto, Canada

Gerard A, Kappelmeyer O: The Soultz-Sous-Forest project. Geothermics 1987, 16(4):393–399. 10.1016/0375-6505(87)90018-6

Hamdy SS, Rashad SM, Blank HR: Spectral analysis of aeromagnetic profiles for depth estimation principles, software, and practical application. U. S. Geol. Sur, Open-File Report; 1984.

Holmberg H, Naess E, Evensen JE: Thermal Modeling in the Oslo rift. In Norway. Proceedings, 37th workshop on geothermal reservoir engineering, Stanford University; 2012.

Hubbard FA: Precambrian crustal development in western Nigeria: indications from the Iwo region. Bulletin of geological society of America. 1975, 86: 548–554. 10.1130/0016-7606(1975)86<548:PCDIWN>2.0.CO;2

Jaupart C, Mareschal JC: Constraints on crustal heat production from heat flow data. In Treatise of geochemistry (3): the crust. Rudnick, Elsevier; 2003:65–84. 10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/03017-6

Joshua EO, Alabi OO: Patterns of radiogenic heat production in rock samples of southwestern Nigeria. J Earth Sc. Geotech. Eng. 2012, 2(2):25–38.

Kappelmeyer O, Haenl R: Geothermics. Borntraeger, Berlin; 1974.

Lachenbruch AH: Crustal temperature and heat production: implications of the linear heat flow relation. J. Geophy. Res. 1970, 75: 3291–3330. 10.1029/JB075i017p03291

Lee WHK, Uyeda S (1965) Review of heat-flow data. W.H.K. Lee, Terrestrial Heat-Flow. Geophys. Monogr. Am. Geophys. Union, pp 87–190. ISBN 8

Loehnert EP: Hydrochemical and isotope data on Ikogosi Warm Spring southwestern Nigeria. Geothermics. Thermal-Mineral Waters and Hydrology. Theophratus,, Athens; 1985.

Lowrie W: Fundamentals of geophysics. Cambridge University Press, UK; 1997.

Maden N: Crustal thermal properties of the Central Pontides (Northern Turkey) deduced from spectral analysis of magnetic data. Turkish J Earth Sc. 2009, 18: 1–10.

Marciniszyn T, Sieradzki A, Poprawski R: Resonance phenomenon in the quartzite from Jeglowa (Poland). AGH J. Mining Geoengineering. 2013, 37(1):51–58. 10.7494/mining.2013.37.1.51

Mareschal JC, Jaupart C (2013) Radiogenic heat production, thermal regime and evolution of continental crust. Tectonophysics, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2012.12.001

Masters G, Constable S: SIO103. Introduction to geophysics (4), Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics; 2013.

Mayhew MA: Curie isotherm surfaces inferred from high altitude magnetic anomaly data. J Geophys. Res. 1985, 90(B3):2647–2654. 10.1029/JB090iB03p02647

Mbonu WO: The trends and geologic consequences of belts of epeirogeny in Nigeria. Book of Abstracts, Nigerian, Mining and Geosciences Conference, Kaduna; 1990.

Mishra DC, Naidu PS: Two-dimensional power spectral analysis of aeromagnetic fields. Geophysical Prospecting 1974, 22: 345–353. 10.1111/j.1365-2478.1974.tb00090.x

Nagata T: Rock magnetism. Maruzen, Tokyo; 1961.

Ojo JS, Olorunfemi MO, Falebita DE: An appraisal of the geologic structure beneath the Ikogosi Warm Spring in south-western Nigeria using integrated surface geophysical methods. Earth Sciences Research Journal 2011, 15(1):27–34.

Okeyode IC: Determination of activity concentrations of natural radionuclides and radiation hazard indices in the sediments of Ogun river. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Ibadan; 2012.

Okubo Y, Matsunaga T: Curie point depth in northeast Japan and its correlation with regional thermal structure and seismicity. J. Geophysical Research 1994, 99(B11):22363–22371. 10.1029/94JB01336

Okubo Y, Graf RJ, Hansen RO, Ogawa K, Tsu H: Curie point depths of the Island of Kyushu and surrounding areas, Japan. Geophysics 1985, 53(3):481–494. 10.1190/1.1441926

Okubo Y, Tsu H, Ogawa K: Estimation of Curie point temperature and geothermal structure of Island arc of Japan. Tectonophysics. 1989, 159: 279–290. 10.1016/0040-1951(89)90134-0

Okubo Y, Matsushima J, Correia A: Magnetic spectral analysis in Portugal and its adjacent seas. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 2003, 28: 511–519. 10.1016/S1474-7065(03)00070-6

Olade MA, Elueze AA (1979) Petrochemistry of Ilesha amphibolites and Precambrian crustal evolution in the Pan-African domain of SW Nigeria. Precambrian Resources:303–318

Oladipo AA, Oluyemi EA, Tubosun IA, Fasisi MK, Ibitoye FI: Chemical examination of Ikogosi warm spring in south western Nigeria. J. Appl. Sc. 2005, 5: 75–79. 10.3923/jas.2005.75.79

Olujide PO, Udoh AN (1989) Preliminary comments on the fracture systems of Nigeria. In: Proceedings of the national seminar on earthquakes in Nigeria. Ajakaiye, D. E.; Ojo, S. B. and Daniyan MA, pp 97–109

Oyinloye AO: Genesis of the Iperindo gold deposit, Ilesha schist belt, southwestern Nigeria. Unpublished thesis of University of Wales, UK; 1992.

Oyinloye AO (2011) Geology and geotectonic setting of the basement complex rocks in southwestern Nigeria, Implications on provenance and evolution, earth and environmental sciences. Dr Imran Ahmad Dar, Tech, . ISBN ISBN: 978-953-307-468-9, [http://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs-wm/24552.pdf]

Pollack HN, Chapman DS: Mantle heat-flow. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1977, 34: 174–184. 10.1016/0012-821X(77)90002-4

Pollack HN, Hurter SJ, Johnson JR: Heat flow from the earth’s interior: analysis of global data set: Reviews of Geophysics. 1993, 31: 267–280.

Ragland PC, Rogers JJW: Variation of thorium and uranium in selected granite rocks. Geochim and Cosmochim. Acta 1961, 25: 99–109. 10.1016/0016-7037(61)90127-2

Rajaram M, Anand SP, Hemant K, Purucker ME: Curie isotherm map of Indian subcontinent from satellite and aeromagnetic data. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2009, 281: 147–158. 10.1016/j.epsl.2009.02.013

Rogers AS, Imevbore AMA, Adegoke OS: Physical and chemical properties of Ikogosi Warm Spring, western Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Mining Geology 1969, 4: 1–2.

Ross HE, Blakely RJ, Zoback MD: Testing the use of aeromagnetic data for the determination of Curie depth in California. Geophysics. 2006, 71(5):L51-L59. 10.1190/1.2335572

Rybach K: equation for Radiogenic heat production. In An introduction to geophysical exploration. Philip AO, McGraw Hill, New York; 1988.

Salem A, Ushijima K, Elsiraft A, Mizunaga H (2000) Spectral analysis of aeromagnetic data for geothermal reconnaissance of Quseir area, northern Red Sea, Egypt. Proceedings of the world geothermal congress:1669–1674

Schlinger CM: Magnetization of lower crust and interpretation of regional crustal anomalies: example form Lofoten and Vasteralen. Norway J. Geophys. Res. 1985, 90(11):484–11504.

Sharma PV: Environmental and engineering geophysics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 2004.

Shuey RT, Schellinger DK, Tripp AC, Alley LB: Curie depth determination from aeromagnetic spectra. Geophys. J. Roy. Astr. Soc. vol. 1977, 50: 75–101.

Silva JBC: Reduction to the pole as an inverse problem and its application to low-latitude anomalies. Geophysics 1986, 51(2):369–382. 10.1190/1.1442096

Spector A, Grant FS: Statistical models for interpreting aeromagnetic data. Geophysics 1970, 35: 293–302. 10.1190/1.1440092

Stacey FD: Physics of the earth. Wiley, 2nd ed, New York; 1977.

Stampolidis A, Tsokas G: Curie point depths of Macedonia and Thrace, N. Greece. Pure and Applied Geophysics 2002, 159: 1–13. 10.1007/s00024-002-8752-5

Stein CA (1995) Heat flow of the earth. Global earth physics. American Geophysical Union AGU Reference shelf 11

Stuwe K (2008) Principles of heat flow modelling., [http://www.geomodeller.com/co/papers_presentations/papers/w_pap_geothermal/principles_of_heat_flow_modelling_stuwe08.pdf]

Swanberg CA: Vertical distribution of heat generation in the Idaho batholiths. J. Geophy. Res 1972, 77: 2508–2513. 10.1029/JB077i014p02508

Tanaka A, Okubo Y, Matsubayashi O: Curie-temperature isotherm depth based on spectrum analysis of the magnetic anomaly data in east and southwestern Asia. Tectonophysics 1999, 306: 461–470. 10.1016/S0040-1951(99)00072-4

Trifonova P, Zheler Z, Petrova T: Curie point depths of the Bulgarian territory inferred from geomagnetic observations. Bulgarian Geophysical Journal 2006, 32: 12–23.

Trifonova P, Zheler Z, Petrova T, Bojadgieva K: Curie point depths of the Bulgarian territory inferred from geomagnetic observations and its correlation with regional thermal structure and seismicity. Tectonophysics 2009, 473: 362–374. 10.1016/j.tecto.2009.03.014

Tsokas G, Hansen RO, Fyticas M: Curie point depth of the Island of Crete (Greece). Pure and Appl. Geophys. 1998, 159: 1–13.

Verheijen PJT, Ajakaiye DE: Heat-flow measurements in the Ririwai ring complex, Nigeria. Tectonophysics 1979, 54: T27-T32. 10.1016/0040-1951(79)90108-2

Wright JB: Fracture systems in Nigeria and initiation of fracture zones in South Atlantic. Tectonophysics 1976, 34: 43–47. 10.1016/0040-1951(76)90093-7

Yawsangratt S: A gravity study of northern Botswana: a new perspective and its implications for regional geology. Thesis, International Institute for Aerospace Survey and Earth sciences, The Netherlands; 2002.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the anonymous reviewers and editors whose thorough, critical and constructive comments greatly contributed to improve this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EMA carried out the data acquisition and processing, participated in research analysis, drafting of the manuscript and interpretation of results. KML participated in supervision of processing, review of technical processing steps, assessment and analysis of results and approval of the version to be published. ACE participated in review and analysis of results. OA participated in data assessment and revision of manuscript. KAM participated in data processing and analysis, revising the draft manuscript and interpretation of results. AAL participated in data assessment and revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abraham, E.M., Lawal, K.M., Ekwe, A.C. et al. Spectral analysis of aeromagnetic data for geothermal energy investigation of Ikogosi Warm Spring - Ekiti State, southwestern Nigeria. Geotherm Energy 2, 6 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40517-014-0006-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40517-014-0006-0