Abstract

This study aims to provide a better understanding of why and how entrepreneurial education increases the inclination to start-up. The study investigates the moderating role of team cooperation on the effect of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion. Survey results from 221 undergraduate students from entrepreneurship programs were used for correlation, regression, and mediation analysis. By integrating social cognitive theory and self-regulation theory, this study proposes a dual-process model and investigates the mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion on the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention. Moreover, this study enhances our knowledge of why and how entrepreneurial education improves business students’ entrepreneurial intention. It also contributed to the entrepreneurial education literature by testing the role of team cooperation as the boundary condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship as a planned and purposeful act (Bird, 1988; Curran & Stanworth, 1989; Katz & Gartner, 1988) is popular with many stakeholders including policymakers, academician, and students (Mwasalwiba, 2010). Entrepreneurial education is defined as a whole education and training activity (whether it is an educational system or a non-educational system) that try to develop participants’ entrepreneurial intention or some factors that affect the intention, such as knowledge, desirability, and feasibility of the entrepreneurial activity (Liñán, 2004). Since Harvard Business School opened its first education program in 1945, entrepreneurial education has been spreading over the few decades at a fairly rapid pace (Liñán, 2004), attracting intensive research interest among entrepreneurship scholars (Mwasalwiba, 2010). Researchers have found that entrepreneurial education is related to career choice and personal skills. For example, research finds that entrepreneurial education is positively related to entrepreneurial attitudes and skills (Fiet, 2014). Audia, Locke, and Smith (2000) indicate that entrepreneurship is an important factor for the development of an economy. Hindle and Rushworth (2002) established that entrepreneurship is a driver of economic growth and national prosperity.

Colleges and universities have realized the value of entrepreneurship education and attempt to promote students’ personal development through an entrepreneurship education program. The basic function of entrepreneurship education is to apply for a job and to create new jobs. However, the great investment in entrepreneurship education in colleges and universities does not significantly improve the entrepreneurial rate of college students (Shen, Chen, & Chen, 2010). Mycos’ research group released the “China employment report” and pointed out that the 2007 and 2008 university graduates’ entrepreneurship ratio were only about 1%, 2011 university graduates’ entrepreneurship ratio was 1.6%, and 2017 university graduates’ entrepreneurship ratio was 3%. The high investment in entrepreneurship education cannot improve students’ entrepreneurial rate in a short period of time; it stems from the time delay effect of entrepreneurship education, which means that students have a lag period of 10 years from accepting entrepreneurship education to actual business (Shen et al., 2010). Due to the time lag of entrepreneurial education, researchers tend to use entrepreneurial intentions rather than real entrepreneurial behaviors to judge the effectiveness of entrepreneurial education; the research perspective of entrepreneurship education has also begun to change from “establishing enterprises” to “entrepreneurial attitudes” (Mwasalwiba, 2010). Hattab (2014) has demonstrated that entrepreneurship education can improve entrepreneurial intentions through individual attitudes and cognition. However, despite these benefits, limited research investigates the underlying mechanism of how and why entrepreneurial education works for increasing students’ entrepreneurial intentions, which can help us to better understand the entrepreneurial process.

In the literature of entrepreneurship education on the impact of entrepreneurial intentions, the original researchers focused on individual personality traits, proposing that personality traits influence their decision to start a business (Nelson, 1977). Later, researchers began to pay attention to demographic variables including gender, age, education level, and so on (Barnir, Watson, & Hutchins, 2011; Martin, Mcnally, & Kay, 2013). Due to the relatively low level of personality traits, researchers gradually turned to cognitive theory to study the impact of entrepreneurial individual differences on entrepreneurial activity (Donnellon, Ollila, & Middleton, 2014; Nanda & Sørensen, 2010; Sivarajah & Achchuthan, 2013). More and more researchers begin to explore the mystery of the entrepreneur’s cognitive model from the cognitive theory perspective. Entrepreneurial education is a practical course. In China, many entrepreneurial education courses are not like traditional courses; students only need to sit in the classroom and listen to the teacher’s lectures. Instead, they can be divided into different entrepreneurial groups to discuss entrepreneurial programs; students need teamwork to promote the formation and execution of business plan in the curriculum. Therefore, team variables will have an important impact in the entrepreneurial education mechanism. Although some researches mentioned the impact of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intentions, to our knowledge, few empirical research studies the impact of team variables on entrepreneurship education in the classroom, and few researchers have studied the role of emotions in this mechanism.

Young and Sexton (1997) point out that in entrepreneurship education, researchers should focus on the areas of social cognition, psychological cognition, and spiritualist or ethics. The social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986) focuses on the reinforcement and observation that is given across parents, educators, and friends (Martin et al., 2013). Entrepreneurial education including the observation of former entrepreneurs will intervene upon the cognitive factors (self-efficacy) of the students and can help them to decide their own intentions and behavior (Ajzen, 1985). Based on self-regulation theory, Cardon, Wincent, Singh, and Drnovsek (2009) analyze the mechanism of entrepreneurial passion and establish the Entrepreneurial Passion Model, which proposes that entrepreneurial passion as a kind of emotion, when motivated, will culminate the outcome of entrepreneurship. Although in the past point of view, emotions and cognition are essentially inconsistent, scholars now recognize that cognition and emotion can act as a coherent, interrelated system that works together toward the desired goal of regulating behavior (Pham & Avnet, 2004). Therefore, we have reason to assume that entrepreneurship education can influence entrepreneurial intention through both cognitive and emotional pathways, and we also consider the influence of team-level variables in entrepreneurship education.

Meta-analysis reveals that several factors will affect the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention such as contextual factors (national policy, social environment, culture), an individual’s background (personality, family environment, family and friends support), and the operation of entrepreneurial education (teaching method, course setting) (Fiet, 2014). In terms of personal background, most researches focus on the individual’s gender (Chen, Greene, & Crick, 1998; Hao, Seibert, & Hills, 2005; Haus, Steinmetz, Isidor, & Kabst, 2013) and entrepreneurial family background (Hout & Rosen, 1999; Tierney & Farmer, 2002; Zellweger, Sieger, & Halter, 2011). Some studies based on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1985; Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen, 1991) focus on the cognitive aspects of individuals (Solesvik, Westhead, Matlay, & Parsyak, 2013; Zampetakis, Gotsi, Andriopoulos, & Moustakis, 2011). However, recent entrepreneurial education researchers indicate that the factor of individuals’ emotion also plays an important part in the research (Donnellon et al., 2014; Fellnhofer, 2017). Nowadays, entrepreneurship courses are taught in a group manner; the climate of the whole team may indeed affect the outcome of the entrepreneurial education, so support from peers (Falck, 2012) as an important team variable should also be considered. Lack of the empirical studies in emotional context and almost no empirical research at the team level call into question the generality of findings in entrepreneurial education; more research should focus on the emotional and team-level factors to increase the generality of the findings.

In view of the above research gap, the first purpose of this paper is to provide a better understanding of why and how entrepreneurial education increases the inclination to start-up. By integrating social cognitive theory and self-regulation theory, we propose that entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion work as the underlying mechanisms to explain the effect of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intention. The second purpose of this paper is to test the moderating role of team cooperation on the relationship between entrepreneurial education and two individual motivational constructs. Specifically, we assert that when the level of team cooperation is high, entrepreneurial education will be more likely to improve individuals’ entrepreneurial cognition and emotion. The third purpose is to increase the generality of the entrepreneurial education research and responses to the call for more entrepreneurial education research in team level.

This paper makes three distinctive contributions to the literature. First, this paper explores the role of team cooperation in the process of entrepreneurial education. The theory of social cognitive and self-regulation emphasize the effects of the external environment on the internal mechanism of the individual; the team in the entrepreneurship education course as an external variable closest to the individual in this environment should be considered in literature. The results of the study show that when the team’s level of cooperation is high, students will obtain a higher level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and have higher entrepreneurial passion. In other words, the relationship between entrepreneurial education and two types of entrepreneurial motivational factors will be strengthened. This finding contributes to the entrepreneurial education literature by providing an alternative insight on the role of team cooperation.

Second, a dual-process model is proposed in this paper. Specifically, this study analyzes the influence mechanism of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intention from two paths of cognition and emotion; it generalized the social cognitive theory and self-regulation theory to illustrate why entrepreneurial education elevates students’ entrepreneurial intention. According to social cognitive theory and self-regulation theory, as an external intervention, entrepreneurial education will have a certain impact on individual cognition and emotion, which in turn will produce the corresponding entrepreneurial outcome. Therefore, when students perceive a high level of entrepreneurial education, they tend to have a high level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and passion, which further improve the entrepreneurial intention. This study contributes to the entrepreneurial education literature by presenting an integrated insight of the corresponding research.

Third, this study extends our understanding of how entrepreneurial intention influenced by teamwork and individuals’ motivational factors during the process of entrepreneurial education. The results of this study increase to generality of entrepreneurship education research and responses to the call for more entrepreneurial education research in different aspects.

This paper also has a certain impact on the practice of entrepreneurial education in the Chinese context. The influence mechanism of entrepreneurial education proposed in this paper affirms the importance of teamwork in the curriculum. At the same time, teachers should cultivate students’ self-confidence and entrepreneurial passion during the teaching process.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Self-efficacy refers to a task-specific self-confidence or a person’s perception of their own abilities to acquire certain high-performance outcomes (Audia et al., 2000); Shane, Locke, and Collins (2004) describe that self-efficacy encourages one to persevere in many of the setbacks and challenges encountered in the entrepreneurial process. According to the social cognitive theory (SCT) developed by Bandura (1986), a person’s sense of self-efficacy can be affected by several processes including enactive mastery, role modeling, and vicarious, social persuasive. Individuals tend to choose high personal control situations that they expect, but avoid their expected low control situations (Wood & Bandura, 1989). Bandura (1986) concluded that through knowledge transfer and acquisition of related skills, education can improve self-efficacy and play a preparatory role in new venture start-up. Furthermore, researches find that entrepreneurship education is associated with a sense of self-efficacy, which may improve entrepreneurial intention (Hao et al., 2005).

H1a: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention.

Cardon, Zietsma, Saparito, Matherne, and Davis (2005) compared the process of establishing a business to the well-known process of raising children and proposed that the process of entrepreneurship should be discussed from an emotional point of view. Donnellon et al. (2014) followed up on a college start-up course found that entrepreneurial education can help build students’ entrepreneur identity; entrepreneurial passion is generated when entrepreneurs experience a strong identity (Murnieks & Mosakowski, 2006). Further, Wright, Carver, and Scheier (1998) put forward the self-regulation theory, the core of the self-regulatory process is that the human agency and the human response are consistent with the thinking of entrepreneur that recognizes opportunities lie between the individual and the environment. Based on the theory, Cardon et al. (2009) theorized a conceptual framework to elaborate how and why entrepreneurial passion might coordinate the outcome of the entrepreneurship. In the model of entrepreneurial passion, Cardon expounded that the entrepreneurial passion affects the entrepreneur’s effectiveness in identifying opportunities.

H1b: Entrepreneurial passion mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention.

Martin et al. (2013) argue that the advantages of entrepreneurial education are conditional and suggest that future researches focus more on the regulatory variables related to entrepreneurial education. Frese, Bausch, Schmidt, Strauch, and Kabst (2012) also suggest that variables should be considered when research at the individual level is different. A deep analysis of the two theories mentioned above can be found that social cognitive theory and self-regulation theory not only emphasize the intrinsic cognitive and emotional mechanisms of individuals, but also emphasize the support and influence of external environment such as peers on individuals (Bandura, 1986; Cardon et al., 2009; Wright et al., 1998).

The role of peers in the formation of entrepreneurial tendencies is considerably less prominent in the literature (Falck, Örtengren, & Rosenqvist, 2012). A rare correlation study focuses on education after starting a business or after labor market entry. For instance, Nanda and Sørensen (2010) research in the workplace and peer effect shows that having a former colleague’s experience in entrepreneurship would increase the possibility of becoming an entrepreneur. This opinion also applies to the entrepreneurial education; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, and Turner (2007) consider teamwork as a strategic competencies associated with enterprising. Further, in knowledge-intensive teamwork, the members’ cognitive abilities and their cooperation determine the efficiency and quality of their performing the team task (Hai, 2003). Gompers, Lerner, and Scharfstein (2005) proposed that individuals who work for a start-up company are more likely to become entrepreneurs; it can only be attributed in part to the spread of entrepreneurial identity (Frese et al., 2012). When a particular identity is activated, entrepreneurial passion mobilizes the self-regulation process of entrepreneurs that is directed toward effectiveness in the pursuit of the corresponding entrepreneurial goal; the pursuit of this goal will also involve the cognition of entrepreneurial identity (Cardon et al., 2009). In this case, team cooperation may affect the relationship between entrepreneurial education and individual cognition and emotion.

H2a: Team cooperation moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy, such that the relationship is stronger when team cooperation is high than low.

H2b: Team cooperation moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial passion, such that the relationship is stronger when team cooperation is high than low.

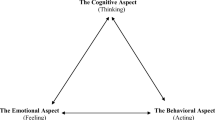

Based on the above elaboration, this paper explains the impact mechanism of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention from two aspects of cognition and emotion, integrating the above moderating effects in the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention; we posit the following moderated mediation model in this study. Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical model of the paper.

H3a: Team cooperation moderates the indirect effect between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

H3b: Team cooperation moderates the indirect effect between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurial passion.

Method

Sample and procedure

The data for this study were collected from undergraduate students who have taken the entrepreneurial course for business students at Shanghai University. The entrepreneurial course lasted for 10 weeks, and we collect our data at different times of the same year respectively in order to avoid the common method biases: There are totally 326 students in the entrepreneurial course; we make full use of resource to invite all the students to participate in our survey. With the help of teachers and students, we distributed paper questionnaires to all students participating in the course. After deleting the incomplete and irregular questionnaires, 221 questionnaires were used in the analysis, representing the response rates of 67.8%. The items of questionnaire is present in Additional file 1.

The demographic information of the respondents is presented in Table 1. Of these respondents, 83 were male (37.6%) and 138 were female (62.4%). Seventy-seven (34.8%) participants’ GPA was below 3, and 144 (65.2%) students’ GPA was higher than 3, but none of the students had got more than 4. According to the survey, 34 (15.4%) of the respondents had experience in entrepreneurship. In addition, 35.3% of the respondents’ immediate family members and 39.4% of the respondents’ friends have either successful or unsuccessful entrepreneurial experiences.

Measures

All the measures used in the current study were employed from the established scale. Unless otherwise stated, respondents answered all the measures based on 5-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” Research data were collected in China, and all the measurement scales in the current study were originally developed and validated in English; back-translation procedure was applied to translate the measures from English to Chinese (Brislin, 1980). Different authors separately translated the scales into Chinese, then translated it into English, and made detailed comparisons to ensure the accuracy of the measurement.

Entrepreneurial education was measured by Walter and Block’s (2016) four-item scale. Sample item includes “My school education helped me develop my sense of initiative a sort of entrepreneurial attitude” and “My school education made me interested to become an entrepreneur”. Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from extremely disagree (= 1) to extremely agree (= 5). Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.81.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy was measured by Tierney and Farmer’s (2002) four-item scale. Sample item includes “I have confidence in my ability to solve problems creatively” and “I am very good at developing another set of ideas from other people’s ideas”. Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.85.

Entrepreneurial passion was measured by Cardon et al.’s (2009) 12-item scale. Sample item includes “It is exciting to figure out new ways to solve unmet market needs that can be commercialized” and “Being the founder of a business is an important part of who I am”. Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.93.

Entrepreneurial intention was measured by Hu, Jiang, and Luo’s (2016) four-item scale which was tested in a Chinese environment. Sample item includes “I will actively learn about entrepreneurial knowledge and learn about the detailed process of entrepreneurship”. Participants described how they generally feel on a 5-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.90.

Team cooperation was measured by Shen and Benson’s (2016) three-item scale. Sample item includes “Students are willing to sacrifice their self-interest for the benefit of the team”. Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.89.

Table 2 presents information about measured variables, including source, sample item, and reliability.

Prior studies on entrepreneurial intention have identified several potential confounders that should be considered in the study (Ronstadt, 1985). Following their research, we controlled respondents’ gender, GPA, and the initial value of entrepreneurial intention as potential control variables.

Results

Before examining the hypotheses, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity by using LISREL 8.80. Table 3 describes the results of confirmatory factor analysis. Our baseline model included entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion, and team cooperation. The five-factor model had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 486.46, df = 125, p ≤ .000; RMSEA = 0.11, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95). Additionally, all factor loadings were significant, indicating convergent validity (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). We also compared different alternative four-factor models by randomly combining two variables (see Table 1). The five-factor model fit the data considerably better than all of the alternative four-factor models. Therefore, the discriminant validity of the constructs was confirmed, and all five constructs were applied in further analyses.

Descriptive statistics

Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, and zero-order Pearson correlations of all the key variables. Results found that entrepreneurial education was positively related to entrepreneurial self-efficacy (r = 0.351, p < 0.010), entrepreneurial passion (r = 0.668, p < 0.010), and entrepreneurial intention (r = 0.557, p < 0.010). In addition, both self-efficacy (r = 0.502, p < 0.010) and passion (r = 0.720, p < 0.01) were positively related to entrepreneurial intention. These results initially support our hypothesis.

Hypothesis test

We conducted hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test our hypotheses. In hypothesis 1a and hypothesis 1b, we predicted that entrepreneurial self-efficacy (H1a) and passion (H1b) mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention. We test these hypotheses according to the following procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986): (1) the criteria (entrepreneurial intention) must relate to the predictor (entrepreneurial education); (2) the predictor must relate to the mediator (self-efficacy and passion); (3) the mediator must relate to the criteria; and (4) the effect of the predictor on the criteria must be reduced after controlling for the mediator. As shown in Table 2, entrepreneur education was positively related to entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.355, p ≤ 0.001, M7) and was positively related to self-efficacy (β = 0.269, p ≤ 0.001, M1) and passion (β = 0.536, p ≤ 0.001, M4). Self-efficacy (β = 0.133, p ≤ 0.050) and passion (β = 0.450, p ≤ 0.001) were positively related to entrepreneurial intention. After controlling the two mediators, entrepreneur education was not significantly related to entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.077, n.s.). Consequently, self-efficacy and passion partially and fully mediated the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention. Thus, H1a and H1b were supported.

Hypothesis 2a and hypothesis 2b proposed that team cooperation moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial education with entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion, respectively. As shown in Table 5 (model 1 and model 4), entrepreneurial education was positively related to self-efficacy (β = 0.269, p ≤ 0.001) and passion (β = 0.536, p ≤ 0.001). After controlling the role of moderator, the interaction term (model 3 and model 6) between entrepreneurial education and team cooperation was positively related to self-efficacy (β = 0.193, p ≤ 0.050, M3) and passion (β = 0.162, p ≤ 0.001, M6), supporting hypotheses 2a and 2b.

Hypotheses 3a and 3b propose that team cooperation moderates the indirect effect between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention via self-efficacy and passion. Therefore, we used PROCESS macro to test the conditional indirect effects. By bootstrapping 1000 samples, the indirect effect between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention via self-efficacy was significant when team cooperation was high (bias-corrected confidence intervals 0.077, 0.256), but was non-significant when team cooperation was low (bias-corrected confidence intervals − 0.081, 0.098). The index of moderated mediation showed that the difference between these two indirect effects was significant (bias-corrected confidence intervals 0.431, 0.193). Besides, the indirect effect between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention via passion was significant when team cooperation both was high (bias-corrected confidence intervals 0.325, 0.675) and low (bias-corrected confidence intervals 0.154, 0.397). The index of moderated mediation showed that the difference between these two indirect effects was significant (bias-corrected confidence intervals 0.687, 0.244). Therefore, hypotheses 3a and 3b got supported.

Discussion

The results supported all the hypotheses. Specifically, first, entrepreneurial education positively affected the entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion of individuals. Team cooperation significantly moderated the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial passion. In particular, when students perceive a high level of team cooperation, they are more likely to strengthen the effect of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion. Besides, we obtained that entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion severs as underlying mechanisms by mediating the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention. In addition to this, we found significant moderated mediation effect by team cooperation on the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention through both emotional and cognitive pathways.

Limitations and future research suggestions

Despite the advantages mentioned above, there are some limitations needed to be highlighted in this study. First, this study only collected data from one business school. Therefore, the generality of the findings may be a question. In addition, it is probably too short to explore the changes of entrepreneurial intention in the process of entrepreneurial education in 10 weeks lag. Subject to the Chinese academic system, a single entrepreneurial course is only maintained for about 10 weeks. Future research may consider longitudinal research design to analyze the causal relationship among entrepreneurial education, the motivational factors of individual, teamwork variables, and entrepreneurial intentions.

Second, this study did not consider other types of support in the entrepreneurial education process. In addition to the variables of team cooperation, other group dynamics has not been discussed; their friends’ support as another type of peer support may also help them make sense of the process of entrepreneurial education. Therefore, future research should control these factors and see whether entrepreneurial education can provide addition variance in explaining the effect on entrepreneurial outcomes.

Third, in addition to entrepreneurship education, other antecedents may also have an impact on entrepreneurial intentions. For example, the personal role model or the personal traits may affect the mechanisms of individual’s cognitive and emotional and then influence their entrepreneurial intention (Pruett, Shinnar, Toney, Llopis, & Fox, 2009; Sánchez, 2011). Future research can try to explore other factors that may affect entrepreneurial intentions.

Conclusion

Building on the social cognitive theory and self-regulation theory, our studies tested the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion, the moderating role of team cooperation, and moderated mediation effect by team cooperation on the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention through both emotional and cognitive pathways. This study extends our knowledge of how entrepreneurial education helps to increase individuals’ entrepreneurial education. Furthermore, the finds of this study provide evidence that individuals who perceive high team cooperation may focus more on self-motivational factors (self-efficacy and passion) and in turn affect their entrepreneurial intention in the process of entrepreneurial education.

References

Anderson J C, Gerbing D W. Structural equation modeling in practice : A review and recommended two-step approach[J]. Psychological Bulletin, 1988, 103(3):411–423.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Ajzen, I. (1988). “Attitudes, personality and behavior. Milton Keynes.” Open University Press. Ajzen, I.(1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Audia, P. G., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2000). The paradox of success: An archival and a laboratory study of strategic persistence following radical environmental change. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 837–853.

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373.

Barnir, A., Watson, W. E., & Hutchins, H. M. (2011). Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(2), 270–297.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Introduction to social psychology. In Handbook of cross-cultural psychology, 5 (pp. 1–23).

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532.

Cardon, M. S., Zietsma, C., Saparito, P., Matherne, B. P., & Davis, C. (2005). A tale of passion: New insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 23–45.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? ☆. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

Curran, J., & Stanworth, J. (1989). Education and training for enterprise: Problems of classification, evaluation, policy and research. International Small Business Journal, 7(2), 11–22.

Donnellon, A., Ollila, S., & Middleton, K. W. (2014). Constructing entrepreneurial identity in entrepreneurship education. International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 490–499.

Falck, A. C., Örtengren, R., & Rosenqvist, M. (2012). Relationship between complexity in manual assembly work, ergonomics and assembly quality.

Falck, O. (2012). Identity and entrepreneurship: Do school peers shape entrepreneurial intentions? Small Business Economics, 39(1), 39–59.

Fellnhofer, K. (2017). The power of passion in entrepreneurship education: Entrepreneurial role models encourage passion? Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 20(1), 58–87.

Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 38(2), 217–254.

Frese, M., Bausch, A., Schmidt, P., Strauch, A., & Kabst, R. (2012). Evidence-based entrepreneurship: Cumulative science, action principles, and bridging the gap between science and practice. Foundations & Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 1–62.

Gompers, P., Lerner, J., & Scharfstein, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial spawning: Public corporations and the genesis of new ventures, 1986-1999. Journal of Finance, 60(2), 577–614.

Hai, Z. (2003). Workflow- and agent-based cognitive flow management for distributed team cooperation. Information & Management, 40(5), 419–429.

Hao, Z., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1–1), 267–296.

Hattab, H. W. (2014). Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Egypt. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 23(1), 1–18.

Haus, I., Steinmetz, H., Isidor, R., & Kabst, R. (2013). Gender effects on entrepreneurial intention: A meta-analytical structural equation model. International Journal of Gender & Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 130–156.

Hindle, K., & Rushworth, S. (2002). Sensis GEM Australia, 2002. Swinburne University, p. 58.

Hout, M., & Rosen, H. S. (1999). Self-employment, family background, and race. Social ScienceElectronic Publishing, 35(4), 670–692.

Hu, W., Jiang, Y., & Luo, J. (2016). Under the new normal university students' social network relation with entrepreneurial intention: Entrepreneurship psychological elastic explanation. Science and Technology Progress and Countermeasures, 33(19), 125–131.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133.

Katz, J., & Gartner, W. B. (1988). Properties of emerging organizations. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 429–441.

Liñán, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccolla Impresa/Small Business, 3(1), 11–35.

Martin, B. C., Mcnally, J. J., & Kay, M. J. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 211–224.

Murnieks, C., & Mosakowski, E. (2006). Entrepreneurial passion: An identity theory perspective. Atlanta: Presented at annual meeting of the Academy of Management.

Mwasalwiba, E. S. (2010). Entrepreneurship education: A review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 40(1), 72–94.

Nanda, R., & Sørensen, J. B. (2010). Workplace peers and entrepreneurship. Social ScienceElectronic Publishing, 56(7), 1116–1126.

Nelson, R. E. (1977). Entrepreneurship education in developing countries. Asian Survey, 17(9), 880–885.

Pham, M. T., & Avnet, T. (2004). Ideals and oughts and the reliance on affect versus substance in persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(4), 503–518.

Pruett, M., Shinnar, R., Toney, B., Llopis, F., & Fox, J. (2009). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 15(6), 571–594.

Ronstadt. (1985). The educated entrepreneurs: A new era of entrepreneurial education is beginning. American Journal of Small Business, 10(1), 7–23.

Sánchez, J. C. (2011). University training for entrepreneurial competencies: Its impact on intention of venture creation. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 7(2), 239–254.

Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2004). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279.

Shen, C., Chen, B., & Chen, H. (2010). “Time lag effect” and evaluation of entrepreneurial education effect in entrepreneurship education. Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education, 1(4), 3–7.

Shen, J., & Benson, J. (2016). When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. Journal of Management Studies, 42(10), 1723–1746.

Sivarajah, K., & Achchuthan, S. (2013). Entrepreneurial intention among undergraduates: Review of literature. Social ScienceElectronic Publishing, 5(2), 65–71.

Solesvik, M. Z., Westhead, P., Matlay, H., & Parsyak, V. N. (2013). Entrepreneurial assets and mindsets: Benefit from university entrepreneurship education investment. Education + Training, 55(8/9), 748–762.

Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148.

Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216–233.

Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361–384.

Wright, B. R. E., Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of behavior. Contemporary Sociology, 29(2), 386.

Young, J. E., & Sexton, D. L. (1997). Entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 5(03), 223–248.

Zampetakis, L. A., Gotsi, M., Andriopoulos, C., & Moustakis, V. (2011). Creativity and entrepreneurial intention in young people: Empirical insights from business school students. International Journal of Entrepreneurship & Innovation, 12(3), 189–199.

Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Halter, F. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 521–536.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to teachers and students at the Entrepreneurial class who cooperated with the researchers by filling out the questionnaires and providing information on entrepreneurs.

Availability of data and materials

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Declarations

We declare that the manuscript is original, not previously published, and not under concurrent consideration elsewhere. No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by authors for publication.

There is no funding support for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL carried out the entrepreneurial education studies and was responsible for the literature review and theoretical part of the manuscript. DW participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the data part of the manuscript. The design and collection of the questionnaire was completed by the two authors. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1

The items of questionnaire. (DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Wu, D. Entrepreneurial education and students' entrepreneurial intention: does team cooperation matter?. J Glob Entrepr Res 9, 35 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0157-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0157-3