Abstract

This study adopts a resource-based view to model how location specific-factors among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in coastal environments in developing economies enable them to sustain clusters and contribute to economic growth. Locations of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a crucial role in determining their survival. SMEs agglomerations are often due to natural resource endowments and types of business climate in their environment. The amoebic nature and economic roles they play have made them the bedrock of the micro economy in most economies. This study contributes to the literature on cross-country comparison of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Zhenjiang (China) and in Lagos State (Nigeria).

The methodology used was mainly literature review and secondary research data from World Bank and data sets from China and Nigeria. The findings highlight an upsurge in research on SMEs in developing countries and how these enterprises have used location-specific endowments to mitigate their resource limitation predicament. The learning points are envisaged to contribute to strategic growth in international business and foreign investments, knowledge for policy makers and to generate further comparative location studies in developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Developing economies are prone to weak institutions, fragile business environments, complex economic and social problems such as poverty, unemployment, low per-capita income and unstable economic growth and development. Faced with these complex problems in their weak environments, business activities spring up to escape the poverty trap and maximize opportunities in different locations (Deng, Hofman, & Newman, 2013). SMEs are common in developing countries and are described as nucleus of economic activities, a major source of employment, key contributors to economic growth and are engaged in poverty eradication initiatives globally (Aga, Francis, & Rodríguez-Meza, 2015; Bauchet & Morduch, 2013). However, they are also confronted with diverse problems like financing, low capabilities, fragile structures, lack of technological know-how, capital issues, institutional deficiencies that hinder their survival and business climate when compared with developed economies (Sorasalmi & Tuovinen, 2016).

Based on the strategic roles SMEs perform in the global economy, scholars have investigated SME dynamics in different contexts using different variables and perspectives. However, there is a dearth of studies on SMEs location–specific endowments in coastal locations in Asia and Africa. The question then arises on how they are able to mitigate the adverse effects of their weak institutional environments. We attempt to address this through resource-based view theory (RBV) using location as an independent variable. In the RBV model factors that influence SMEs locations, resource geography and adaptive capabilities are represented in Fig. 1. Extant literature confirms the agglomeration of SMEs clusters in urban cities (Boisot & Child, 1999). This study makes novel contribution to the literature on SME cross-country studies in Asia and Africa by investigating location specific factors in China and Nigeria.

Firstly, we draw our theoretical framework based on resource-based view (RBV) to enrich our understanding of SMEs complex dilemma in developing economies. Secondly, prior SME studies focused on diversity, business complexities, financing and other issues that affect SMEs mostly in developed countries, but this study adopts location-based perspective for SMEs in Zhenjiang, China and in Lagos, Nigeria. Thirdly, this will be the first study on SME Location –Specific study between China and Nigeria. SME environment-enterprise continuum globally has distinct contextual factors influencing performance with business processes often modeled without a holistic examination of context (Novakovic & Huemer, 2014). Finally, our study confirms cross-country complementary synergies, vertical and horizontal networks in both environments.

Conceptual framework

Location offers mixed advantages to enterprises and resource availability enhances growth and survival advantage depending on the size and type of business (See Fig 1). Location specific resources could serve as pull or push factor for SMEs in developing economies. We draw on resource-based view (RBV) theory mainly for its relevance to SMEs in developing economies. Firstly, RBV remains relevant in SMEs studies due to the adaptive and informal structures in most contexts. Thus researchers have engaged in diverse perspectives to investigate this construct through market imperfections, firm sizes, age type, specialization level and resources (H. Lee, Kelley, Lee, & Lee, 2012; Ogunyomi & Bruning, 2015).

Barney (2001) resource based-view suggests the ability of firms to use their resources as a tool for competitive advantage. Most enterprises are small with minimal internal resources at their disposal and are left with the only option of leveraging on synergy of complementary resources in urban locations and environments. This possibility favors the development of clusters with easy access to infrastructural facilities and supply chain opportunities arising from presence of big companies and organizations. The level of availability and access to resources by enterprises in locations could bestow relative competitive advantages that can help them maximize market share and benefit from economies of scale as well as internationalization (Fujita & Thisse, 2013; Porter & Clark, 2000). Small firms in a cluster location are able to benefit from synergy in their business environment and do not necessarily have to own all the resources they need before they have access to them (Lechner & Leyronas, 2012).

However, resultant agglomeration and survival of firms in specific locations has many ties to the enterprise’s ability to maximize its resources at internal and external levels as well as boundary spanning capabilities (Delgado, Porter, & Stern, 2015; Mesquita, 2016). Similarly, resource advantages of enterprises, uneven resource endowment and absorptive capacity contribute to location of clusters in urban and semi-urban areas. Presence of government organizations, agencies, institutions, incubation centers, financial industry and ports provides opportunities for SMEs to lock into the supply chain and business needs in such locations.

Businesses in urban locations enjoy location-specific factors such as infrastructural amenities, value chains, and labor supply with different skill sets. Conversely, in rural locations there are unique resource advantages that are missing in urban locations, such as lower cost of living and doing business, strong cultural and institutional frameworks. Thus, SMEs serve as conduits in the value chain for businesses. Therefore, enterprises engage in boundary spanning activities in their locations to enhance their chances of survival, competitive advantage and internal evaluation of its resources helps shapes its business dynamics, culture, spatial relationships and skill levels (Lindgren, Andersson, & Henfridsson, 2008).

RBV provides a robust perspective and theoretical basis for investigating small businesses positioning, strategic choice and adaptive capacity in their domains and suggests that collaborative, backward and forward integration can help SMEs overcome their resource limitation. Mesquita and Lazzarini (2009) found three core benefits SMEs derive in their location; complementary competencies, shared knowledge and collaboration with other enterprises in utilizing common resources. Several empirical studies affirm the availability and unavailability of tangible and intangible resources as pivotal in shaping SME clusters, infrastructure (Laosirihongthong, Prajogo, & Adebanjo, 2014), Human capital (Miller, Xu, & Mehrotra, 2015; Shaw, Park, & Kim, 2013), capital, finance (Lonial & Carter, 2015), cost of doing business, and accessibility.

Environment of business

Emery and Trist (1965) classification of business environments as existing on a continuum with shades of placid, disturbed-reactive, turbulent and dynamic environments supports existence of agglomeration and clusters in different business spheres and location (Sonobe & Otsuka, 2016). The majority of SMEs in African countries operate in highly volatile and turbulent domains compared to their counterparts in stable and well regulated domains in China, USA and Europe (Child, 1972; Emery & Trist, 1965; Hatch & Cunliffe, 2012).

This study adopts the environment of business analogy rather than business environment and posits the environment of a business contextually depends on interplay of human behavior and group dynamics. Thus, a working definition of environment of business signifies “the totality of transient web of forces, interplay of resultant group dynamics related to business enterprises.”. SME’s environment of business has some similar features and differences in their domains and at the core is a complex network of market, physical and institutional environments. Therefore, several factors influence and hinder SMEs location decisions and location based pull factors draws most enterprises to urban areas while some push factors make large enterprises relocate to industrial sites. The transient structures of these enterprises enable them to thrive in urban centers and engage in commercial and service activities.

Multifaceted nature of SMEs definition in China

The multifaceted nature of China’s economy is reflected in broad SME classifications when compared with yardsticks used in Africa and Europe. This seeming complexity arises from its history, transitions, culture and Government policies. While most governments provide regulatory support and incentives for SMEs, a regulator-operator role of the Chinese government is based on peculiarities of each sector with classification based on operating income, number of employees and total assets (Cunningham, 2011). This multi-layered SME model is tailored to suit the context of their differentiated economic provinces and resources. This model differs sharply from the general classification model applied mostly in Nigeria and developing economies (See Table 1) which does not take cognizance of the peculiarities of each sectors and locations, but revolves around a class band of employees and assets.

Previous studies suggest that SME definition in China has changed more than four times since 1949 (Xue Cunningham & Rowley, 2007) in response to changing realities of the economy and environment of business. For example, what is classified as a small enterprise in some SME sectors in China can be a big organization and blue-chip manufacturing organization in Nigeria due to their size and financial outlay. This is supported by Li, Yang, and Xu (2006) view that historical reasons, gap in regional economic development, creates sharp disparity in distribution and development of SMEs. Nigeria’s National Policy on SMEs adopts a classification based on dual criteria, employment and assets (excluding land and buildings).

China’s multifaceted SME environment is synonymous with peeling an onion the more layers peeled off, the more you realize contextual elements vary across provinces and are mystified by the Law of People’s Republic of China on promotion of small and medium-sized enterprises. This study focuses on the soft variables by examining the strategic roles of these locations in the growth and development of their countries. Li et al. (2006) argues that history and time are fundamental in understanding Chinese SMEs and categorizes the evolution of Chinese SMEs in four phases: “early stage” (1949–1957)“,growth and fluctuation” (1958–1963), “innovative transformation” (1978–1996) and “rapid growth” (1997 - onward). The evolution of Chinese SMEs was initially characterized by the presence of government owned, centrally controlled, provincial SMEs. Market-oriented reforms initiated in the 1980’s by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, resulted in the emergence of private ownership of SMEs. This foundation premise provides a distinct evolutionary exposition on China’s SME transitions from government owned enterprises to private sector enterprises. In essence, business environments are complex systems and the level of complexity varies from location to location and institutional theory suggests that, like onions, organizations exist in layered form with internal and external environment, formal, informal groups and employees (Fuenfschilling & Truffer, 2014).

Research locations

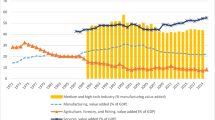

Nigeria’s 2014 and 2015 rebased GDP of $569billion, $481billion and 182 million population makes her the most populous economy in Africa and accounts for 47% of West-Africa population(Bank, 2015). Conversely, China is Asia’s largest country and most populous nation in the world. According to China’s ministry of commerce, SMEs in China exceed 4 million and contributes more than 58% of GDP and taxes; they also spearhead exports and job creation yearly, accounting for about 68% and 75% respectively.

Nigeria’s huge population and economy creates a strategic hotbed for investment with increasing business relationship with China even though they are in distinct continents (Guengant & May, 2013). Nigeria’s coastal location and ports creates a strategic economic hub for global business flows, while proximity of states to the coastal locations offers location–specific benefits with constant supply-chain business activities. Coastal states like Lagos, Port-Harcourt and Cross-River benefit from the inherent economic resources of their coastal locations. The 2010 Lagos State Government Gross Domestic Product (GDP) survey shows that Lagos is the smallest state with only 356,861 ha of land, of which 75,755 ha are wetlands. Its GDP of $80.6billion represents 35.6% of national GDP, larger than the GDP of some African countries, Kenya($66bn), Ghana($62bn) and Tanzania($58bn), (Government, 2010). Similarly, Zhenjiang lies at the intersection of the Yangtze River and the Grand Canal which contains six sub cities, covering an area of 3847 km2 with a population of 3.019 m. In 2003, Zhenjiang’s GDP reached 64.36 billion Yuan. In 2007, it grew to 121.3 billion Yuan and in 2012 it grew 12.8% from the previous year to 263.01 billion Yuan, ranking it 10th among all the cities in Jiangsu (Knowledge, China, 2016a, b; Office, 2016).

Zhenjiang and Lagos offer unique contexts with similar coastal location. The two domains have a small land area compared to other locations in their environment, these seem to exert a positive pull on their economic performance, and SMEs clusters (see Tables 2 and 3). Coastal locations in China offer immense economic benefits, good environment for business opportunities, value chains and outward investments in Africa (Brautigam, 2015).

The mass of SMEs in Zhenjiang and Lagos State is attributable to myriad elements in their locations and though they share similar coastal traits, their nature varies. Lagos is the nucleus and main economic hub of Nigeria with the largest cluster of SMEs, multinationals and corporations. Nigeria’s 2010 National MSME collaborative survey depicts that MSME contributed 46.54% of Nigeria’s s GDP in nominal terms and 55% of GDP in China (National Bureau Of Statistics) (Chinese Cities and Provinces - http://www.chinatoday.com/city/a.htm, National Bureau Of Statistics, Nigeria 2010). In addition, the coastal location of Zhenjiang places it in the economic triadic hub with Shanghai and Beijing (see Fig. 2) and the closer the province, region to any point in this economic triangle the bigger their economic activity. In addition, the Yangtze River or Changjiang River is the longest river in China with a total length of 6300 km (see Table 3). The Yangtze River Delta, flows across 14 cities, offering immense economic advantages to coastal locations and accounts for 42% of rivers in China, this makes coastal locations along its path a channel of import- export harbor (today, 2016).

The majority of OECD enterprises are SMEs; most nations have them in varying proportions at the bottom of the pyramid shaped by the interplay of pressures from local and foreign markets (Library, 2012). On the contrary, North and Smallbone (2000) posits that SMEs in poorly developed locations have a lower inclination to export and innovation doesn’t fully apply to developing nations like Nigeria, where the bulk of agricultural and allied exports is initiated by SMEs in the rural areas due to readily accessible resources. Adopting the resource based view; location is portrayed as an “enabler of resource acquisition and capability development” (Freeman, Styles, & Lawley, 2012). Despite, the divergence in views of classical, neo classical and behavioral location theories and focus on industrial locations, their spatial concentration often spins off the presence of many small business, positioning them to leverage on the economic geography, presence of bigger firms and ancillary elements (Yang, Luo, & Law, 2014).

The strategic positions of Zhenjiang and Lagos seems to offer a “location-specific” edge, attraction and pull across all frontiers of international business with resultant upsurge in population growth, investment climates and attendant problems. Likewise, Porter and Porter (1998) studies on “location, clusters and the new micro economics of competition” offers insights on unraveling and understanding behavioral and location factors that influence firms and small businesses locations. The presence and concentration of large organizations in a location attracts ancillary enterprises, infrastructural amenities and clusters aimed at leveraging on the synergy and economies of scale to sustain their continued existence, innovation and growth.

Physical environment, contextual dynamics models their strategy, forms of innovation, survival rate, competition and behaviors in their entrepreneurial activities (Stearns, Carter, Reynolds, & Williams, 1995) and this substantiates the current density of firms in Lagos and Zhenjiang. Rivalry among firms breeds imitation and innovativeness in the long run though this is moderated by available factors and local demand conditions (Porter & Porter, 1998). This often dictates the possibility of firms moving from imitative, low quality products and services to competition based on differentiation and product innovation (Cockburn, Henderson, & Stern, 2000).

Nigeria’s weak institutional framework has effects on product innovation among firms leading to growing spate of process innovation used mainly as a strategic tool to undercut competition (Mesquita & Lazzarini, 2010). We posit that the resoluteness of these firms is evident in their outward alliances with Chinese firms for executing their product innovation invariably as a cost saving mechanism and comparative cost advantage (Hessels & Parker, 2013).

The level of support enjoyed by Zhenjiang SMEs transcend superficial regulatory support to massive financial and institutional incentives targeted at nurturing and protecting infant industries by government with resultant strategic formation. Growth of clusters in different provinces promote outsourcing, vertical integration, innovation, eliminating barriers to new business formation and location related competitive advantage (Ceglie & Dini, 1999).

Methods

Data

A literature search in Google scholar electronic database was done in November, 2015 and April, 2016 for articles published between 1980 and 2016 using 12 keywords, problems, finance, location, GDP, employment, sub-Sahara, job creation, Nigeria, China, Africa, Europe, Cross-culture (see Fig. 3). We also used datasets from China and Nigeria’s World Bank Enterprise survey 2012, 2014 conducted from April 2014 to February 2015 and November 2011 to March 2013.The datasets sample size comprised of 2676 firm in 19 states of Nigeria and samples from China taken from November 2011 through March 2013 consisted of 2700 privately owned and 148 state-owned firms. World Bank enterprise surveys provide objective data on firms in more than 124 countries and focus on dynamics of factors that shapes the business environment. The Surveys also enjoy wide usage by scholars in cross-country studies and World Bank policy papers due to the standard methodology.

The samples were derived using stratified random sampling, industry, enterprise size, and location (urban). Enterprise size parameters was defined using unified size bands: small (5 to 19 employees), medium (20 to 99 employees), and large (more than 99 employees) see Table 4. These parameters did not account for micro and informal enterprises, which are predominant in developing countries.

The Literature review and secondary data obtained from World Bank Enterprise Surveys, Nigeria and China Bureau of Statisics enhanced representation of our conceptual framework as depicted by the tables and figures in this study.

Results

The evidence from the literature search in Fig. 3 is representative of most databases and a signpost to the dearth of cross-country SME research in Nigeria and sub-Saharan Africa. The literature was skewed mainly towards contextual locations in developed countries of Europe and America. The literature on China SMEs seem to have increased sharply from 2010 to 2016 compared to the preceding 29 year period (1980–2009), this may be attributable to subprime crises. Globally, SMEs were used to jumpstart most economies after the subprime crises, resulting in attentions shifting to emerging economies in Asia and Africa. SMEs witnessed sustained pressure by their governments and economies to create jobs and jump start the process of economic growth and development (Ardic, Mylenko, & Saltane, 2011). This evidence provides justification for studies and increasing focus on developing and emerging economies described as the last frontiers of the globe due to the influx of foreign direct investment.

Evidences from the sample population in Table 4 confirms the structure of SMEs in both contexts, micro and small enterprises form the bulk of enterprises in Nigeria and business climate in China is a major factor for the large size of medium and large enterprises. A major reason for the sharp differences in the SME composition lies in the nature of institutional opportunities and problems in each context. Fig. 4 shows that lack of basic infrastructure facilities for example, electricity poses a major problem for SMEs growth. In Lagos, SMEs account for majority of businesses in the private sector and major commercial cities in China and Nigeria confirms the presence of large clusters. Less than 10% of the literature search was on finance issues, location, GDP, employment, Sub-Sahara, job creation, Nigeria, China, Africa, Europe, Cross-country studies relating to SMEs. Financing problems and practices of informal sector constitute major hindrances to SME growth and location in China (see Fig. 4) and this suggests that most of these enterprises may not be within the scope of regulatory authorities due to their informal and transient business lifespan. Energy problems seems to be a major predicament limiting SMEs growth in Nigeria and this has continually hindered the existence of virile business environment and led to increasing high cost of production and doing business in Nigeria. The unavailability of constant electricity makes most firms to depend on generators to run their businesses, this poses environmental problems .Thus, availability of financing, and energy has continued to influence the location of these enterprises in their domains. The level of corruption in Nigeria is significantly higher when compared to China. Corruption is an endemic problem facing most developing countries and is a reflection of the lax in regulatory and business environment. High poverty level, the cost of doing business, the cost of living in urban area, family commitments, loopholes in regulatory and business environment are some of the factors that promotes corruption.

Discussions

Contribution to development

The clustered nature of SMEs gives room for economies of scale, ideally it is expected to facilitate synergy, specialization, cost reduction via the use of infrastructural facilities available and supply chain processes (S. Lee, Park, Yoon, & Park, 2010). The realities present a sharp disparity while most clusters in Zhenjiang have a well-structured supply chain with robust e-commerce platform that facilitates international businesses, clusters in Lagos are mostly trade, service and import dependent oriented with strategic alliances in Asian Countries.

In addition, apparent infrastructure deficiencies contribute to the high cost of doing business in urban locations, where they are majorly clustered. However, similar findings confirm the resilience of SMEs and outward strategic alliances in different contexts (Brouthers, Nakos, & Dimitratos, 2015). Their development plays decisive role in enhancing economic growth and development. Clustering offers unique benefits and a common feature in China and Nigeria with different growth stage in their life cycles (Rauch, Doorn, & Hulsink, 2014; Tambunan, 2005).

Lagos state economy makes up a significant proportion of the Gross Domestic product(GDP) of Nigeria, despite the small land size, other states with larger land size do not contribute as much as Lagos State. In 2010, Lagos economy GDP stood at = N = 12.091 trillion ($80.61 billion) and accounted for 35.6% of the national GDP and 62.3% of national Non - Oil GDP for the same year (Government, 2010). Lagos GDP and over-stretched population also makes it the most overcrowded state and haven for informal economy.

Migration to Lagos is continuous from all locations in search of greener economic fortunes; this has resulted in a thriving and resilient informal sector and economy. Zhenjiang scenario is a pointer to the importance of economic activities in a location, being one of the smallest cities in China in terms of land area. It occupies the bottom ranking position of 315 out of 319 cities. Zhenjiang’s economy is ranked among the top 58 cities in China out of a total ranking of 319 cities in terms of GDP (Knowledge).

Cost of doing business

Clusters are perceived to lower cost of production, this is location dependent (Ho, Lenny Koh, Karaev, Lenny Koh, & Szamosi, 2007). Lagos and Zhenjiang SMEs have similarities owing to presence of clusters; their location has continued to witness an influx of local and international business, human migration, infrastructure pressures, and higher cost of doing business. Business (2013) business report on Nigeria shows that SME businesses are plagued by high cost of doing business due to poor, unstable energy supply, multiple taxation by strata’s of government, labor cost and poor infrastructural facilities.

SME’s cost of doing business portrays contextual problems that hinder growth. Evidence from World Bank enterprise surveys shows that enterprises in Nigeria have a lack of electricity as their major obstacle. SMEs in China have access to finance, tax rates and activities of the informal sector as major obstacles (see Fig. 4). Nigeria’s government effort in improving cost of doing business is yielding some positive results in some frontiers with Lagos and Ogun states pioneering the streamlining and simplifying processes in registering an enterprise. This has led to a reduction in the number of days it takes to register an enterprise with the corporate affairs commission though the tax burden in the state is still very high. In the past 5 years, medium sized enterprises and large organizations have begun to move out of Lagos due to an increasing tax burden and land space to neighboring states like Ogun state, where the tax rate is much lower and land is readily available.

Though corruption increases cost of doing business, the efforts of regulatory authorities has resulted in increase in ease of business ranking of Nigeria from 170 to 169 in the Bank’s Doing Business 2017 ranking reporting (Bank, World, 2016a, b). Though the change seem insignificant, it is envisaged that this renewed change and on-going anti-corruption drive will trickle down to all sectors in the micro economy.

Capital

The regulator-participator model of Chinese government in promoting and protecting majority of sectors in the economy still leaves small and micro enterprises with capital problems. Thus, resultant use of traditional sets of personal savings, friends and private credits have helped nurture and sustain SME economy (Ayyagari, Demirgüç-Kunt, & Maksimovic, 2010; Lu, Guo, Kao, & Fung, 2015).

Enterprises in Zhenjiang operate in a stable task environment with continuous exchanges within a geographical space (Bourgeois, 1980). Conversely, the volatile business environment prevailing in Nigeria makes enterprises grapple with capital issues making most of them start on trial and error basis. This poor foundation exposes them to high business risks, difficulty in securing financial support from formal institutions and patronage by informal moneylenders at a higher interest rate. Result from the 2010 National MSME Collaborative survey; indicate that SMEs contributed 72% of the nominal GDP in Nigeria. The environment and resilience of these enterprises in surviving despite huge financial shortcomings and problems confronting them favors the apprenticeship model.

Accessing finance

SMEs globally face difficulty in accessing finance from conventional financial institution. However, International Finance Corporation and World Bank efforts at improving their financial problems reveal contextual finance problems requiring homegrown strategies to manage and overcome this predicament. Most SMEs have difficulty accessing loans from banks; most credit officers lack an in-depth understanding of SMEs business cycles, and are averse to lending to them (Du & Banwo, 2015). The Central Bank of Nigeria has continually encouraged banks to design special product lines aimed at meeting their financing needs, yet most commercial banks favor big-ticket loan transactions. However, Diamond Bank of Nigeria Plc has a dedicated SME team and product line designed to help SME loan applicants determine their qualification for a loan facility by simply completing a simplified self-assessment online module. The Bank’s innovative processes favor SMEs banking through reduction of charges on their account. The resultant benefits have spurred up competition from big banks like First Bank, GTbank and Access Bank for SME market share. Though these enterprises are still subjected to double digit interest rates, due to the huge risk exposure of this segment and prevailing macro-economic policies (Berg & Fuchs, 2013). Micro finance banks in Lagos and micro-credit companies in China have non-technical stringent conditions and a better understanding of SME business and financing dynamics and charge interest rates as high as 5% flat monthly (Ehigiamusoe, 2008; Kitching & Woldie, 2004). The timeliness and availability of their loans remain a main attraction regardless of the high interest rates, but their risk appetite and exposures often lack effective risk management structures. Inability of conventional banks to avail soft loans to majority of SMEs creates a huge financial gap; private investors and companies have seized this opportunity not borne out of a desire to provide relief for them but mainly to make a profit.

Wang (2004) asserts that SMEs in China are forced to patronize private loan sharks and informal financing channels primarily due to availability of loans and flexibility in the collateral provision to meet urgent business commitments. SMEs in China enjoy single digit interest rates on deposits and loans from Banks, those in Lagos that have access to bank facilities are exposed to two digit interest rates ranging from as low as 15% to 30% per annum.

This un-level playing field has resulted in an outward strategic alliance by some SMEs with counterparts in Asia to reduce cost of doing business, while those that do not have outward strategic alliances often grapple with high cost of doing business for enterprises with only local alliances and network.

Human capital management

Porter (2000) proposition that a locations prosperity and productivity does not only depend on the competition in industries, but more on “how”. This brings to forefront the strategic role of human capital and group dynamics prevalent in such locations. The organizational behavior framework bears positive or negative effect on the totality of business enterprises in the locations. SMEs face a rather peculiar human capital management, which are usually not well structured in most enterprises. These enterprises attract the type of labor they can afford and the fact that most SMEs business are owned and managed by family members poses grave hindrances to professional management. Hence, SMEs are prone to mistakes in decision-making, fluid participation, human capital management issues. Renaissance capital thematic research report (2013) shows that Lagos is the smallest state in Nigeria (Aliu & Ajala, 2014) and “its population density is equivalent to that of the fifth most densely populated country in the world, and half that of Hong Kong (6800 people per km2) (capital, 2013)”. Population size has a corresponding correlation with the level of informality, economic productivity and growth. We note that Lagos state population is 18% higher than that of Zhenjiang but Zhenjiang’s GDP is 58% that of Lagos state with a much lower population. One major reason for the low productivity of Lagos populations (17.5million) may be traced to high unemployment rate and huge presence of informal sector participants of 2,307,281 persons representing 13% of the population, national unemployment rate was 21.1% of labor force in 2010 (National household and informal sector survey, 2010). Harnessing the latent economic capability of the informal sector in Lagos remains a task for policy makers and Lagos State’s current resident registration scheme will help capture the true size of its inhabitants and economic planning. The Government collaborative partnership and recognition of informal trade associations and groups is yielding positive economic benefits with various grassroots capacity training and skill development opportunities aimed at fusing the informal-formal economy continuum (Meagher, 2013; Onokala & Banwo, 2015).

Infrastructural facilities

The presence and availability of infrastructural facilities correlates with the volume and nature of economic activity in most developing countries. Lagos has the highest concentration of SMEs and basic amenities yet it is still plagued by enterprises performing below optimum level (Du & Banwo, 2015). In unleashing the economic capabilities of SMEs, it is pertinent that stakeholders and Government provide basic amenities necessary for the survival of these enterprises and fast-track the de-regulation and commercialization of the power sector (Usman, Abbasoglu, Ersoy, & Fahrioglu, 2015). A drastic improvement and stability in the energy and electricity supply will have several positive effects on the cost of doing business in Nigeria and standard of living (Ikeme & Ebohon, 2005).

It is a paradox that though Nigeria’s rebased GDP places it as the largest economy in Africa, its neighbor’s in sub-Sahara Africa enjoy better and more stable electricity (Jerven, 2013). Nevertheless, the opportunities in Nigeria’s Energy sector provide latent benefits to investors and the economy, the government has not been transparent in allowing foreign direct investment in this area. It is envisaged that recent commercialization exercise in the power sector, in the long run should result in an improvement in power supply and a sharp upsurge in entrepreneurial and economic activity (Okwuosa & Amaeshi, 2015). SMEs in Zhenjiang are not plagued with energy problems rather the Doing Business Report 2014 suggests other contextual issues like access to finance as a major constraint small enterprises encounter (Business, 2013). The 13 prefectures levels in Jiangsu province are hotbeds for export and import businesses, stable energy and power has given SMEs in China a leveraged advantage with resultant foreign business orders from enterprises and ventures in Africa seeking to take advantage of their low cost and comparative advantage (Hendrischke & Feng, 1999). The establishment of free trade zones in several strategic locations in Nigeria is designed to replicate economic havens in Zhenjiang and Silicon Valley in the USA with independent power generation needed to boost and sustain economic activity (Pigato & Tang, 2015).

The Chinese Government and Chinese enterprises have demonstrated commitment to these special trade zones and the benefits will be immense to both parties and ultimately lead to transfer of technology and massive foreign direct investment (Renard, 2011; Shen, 2013). Africa remains a strategic business partner for China and Chinese government’s involvement in building infrastructural facilities across Nigeria is expected to provide a well-coordinated supply chain network and logistics network to boost economic activity (Bräutigam & Xiaoyang, 2011; Ozawa, 2015). For instance, several Chinese firms are engaged in on-going reconstruction and overhauling of the railway network, building of roads in strategic locations all over Nigeria.

Conclusions

The comparative study of Lagos and Zhenjiang coastal location reveals a myriad of contextual issues and location derived benefits arising from the nature of economic activity. Their strategic coastal domains revealed different levels of economic productivity, contextual issues and regulator-operator environment. Policy makers and stakeholders in Nigeria should intensify efforts to leverage on emerging opportunities in the power sector. Licensing of new private banks in China requires a homegrown Guanxi based approach if they are to be successful in providing capital to SMEs. In the long run SMEs may find it easier to access financing needs from the bank. Investors and investments in Lagos will continue and the completion of the Lekki free trade zone will further bolster the economic ties between China and Nigeria (Ozawa, 2015). Similarly, the early completion of other industrial parks and special economic zones in Ogun state and other locations in Egypt, Ethiopia, Mauritius and Zambia are critical for industrialization drive in Africa and integration into the global value chain (Davies, 2010). Replicating the remodeling and redevelopment model of Chinese cities and provinces is imperative for Lagos State and major cities if they are to maximize their limited land resources and transform their domains into megacities.

Current efforts between the two regional powers in fostering industrial co-operation should be nurtured and Nigeria needs to learn from China’s industrialization strategy of dedication, pragmatism and long-term planning (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015).

Limitations

The findings of this study cannot be generalized due to the limited research location context. Another limitation is the reliance on secondary data, though the sources are reliable, timelines of the data differs and realities change. Data on small and medium enterprises in developing countries are limited due to their transitory nature and short life cycle. Future research should include more study locations and contextual variables.

References

Aga, Gemechu A, Francis, David, & Rodríguez-Meza, Jorge. (2015). SMEs, age, and jobs: A review of the literature, metrics, and evidence. World Bank policy research working paper (7493).

Aliu, I. R., & Ajala, A. O. (2014). Intra-city polarization, residential type and attribute importance: A discrete choice study of Lagos. Habitat International, 42, 11–20.

Ardic, Oya Pinar, Mylenko, Nataliya, & Saltane, Valentina. (2011). Small and medium enterprises: A cross-country analysis with a new data set. World Bank policy research working paper series.

Ayyagari, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2010). Formal versus informal finance: Evidence from China. Review of Financial Studies, 23(8), 3048–3097.

Bank, World. (2015). Nigeria data. From the world bank http://data.worldbank.org/country/nigeria

Bank, World. 30th september, 2015). Nigeria: World Bank. 2016a, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/overview

Bank, World. (2016b). Ease of doing business in Nigeria. Retrieved 27/10/2016, 2016, from http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/nigeria/

Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41–56.

Bauchet, J., & Morduch, J. (2013). Is micro too small? Microcredit vs. SME finance. World Development, 43, 288–297.

Berg, Gunhild, & Fuchs, Michael J. (2013). Bank financing of SMEs in five sub-Saharan African countries: The role of competition, innovation, and the government. World Bank policy research working paper (6563).

Boisot, M., & Child, J. (1999). Organizations as adaptive systems in complex environments: The case of China. Organization Science, 10(3), 237–252.

Bourgeois, L. J. (1980). Strategy and environment: A conceptual integration. Academy of Management Review, 5(1), 25–39.

Brautigam, Deborah. (2015). China-Africa economic cooperation: Dimensions, changes, expectations. AFRICA at a fork in the road, 331.

Bräutigam, D., & Xiaoyang, T. (2011). African Shenzhen: China’s special economic zones in Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 49(01), 27–54.

Brouthers, K. D., Nakos, G., & Dimitratos, P. (2015). SME entrepreneurial orientation, international performance, and the moderating role of strategic alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1161–1187.

Business, Doing. (2013). Doing business 2014: Understanding regulations for small and medium-size enterprises: World Bank publications.

Capital, Renaissance. (2013). Thematic research report: Nigeria unveiled; the thirty shades of Nigeria, from www.rencap.com/eng/download.asp?id=16485

Ceglie, G., & Dini, M. (1999). SME cluster and network development in developing countries: The experience of UNIDO. Geneva: UNIDO Geneva.

Child, J. (1972). Organizational structure, environment and performance. The role of strategic choice. sociology, 6(1), 1–22.

Cockburn, Iain, Henderson, Rebecca, & Stern, Scott. (2000). Untangling the origins of competitive advantage.

Cunningham, Li Xue. (2011). SMEs as motor of growth: A review of China's SMEs development in thirty years (1978-2008. Human Systems Management, 30(1), 39-54.

Davies, M. (2010). How China is influencing Africa’s development (pp. 187–207). South-Africa: China and the European Union in Africa: partners or competitors.

Delgado, M., Porter, M. E., & Stern, S. (2015). Defining clusters of related industries. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(1), 1–38.

Deng, Z., Hofman, P. S., & Newman, A. (2013). Ownership concentration and product innovation in Chinese private SMEs. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(3), 717–734.

Du, Jianguo, & Banwo, Adeleke. (2015). Promoting SME Competitiveness: Lessons from China and Nigeria.

Ehigiamusoe, G. (2008). The role of microfinance institutions in the economic development of Nigeria. PUBLICATION OF THE CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, 32(1), 17.

Emery, F. E., & Trist, E. (1965). The causal texture of organizational environments. Human Relations; Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 18(1), 12–32.

Freeman, J., Styles, C., & Lawley, M. (2012). Does firm location make a difference to the export performance of SMEs? International Marketing Review, 29(1), 88–113.

Fuenfschilling, L., & Truffer, B. (2014). The structuration of socio-technical regimes—Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Research Policy, 43(4), 772–791.

Fujita, Masahisa, & Thisse, Jacques-François. (2013). Economics of agglomeration: Cities, industrial location, and globalization: Cambridge university press.

Government, Lagos State. (2010). Lagos state government gross domestic product (GDP) survey from http://www.lagosstate.gov.ng/GDP2010.pdf

Guengant, J.-P., & May, J. F. (2013). African demography. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 5(3), 215–267.

Hatch, Mary Jo, & Cunliffe, Ann L. (2012). Organization theory: Modern, symbolic and postmodern perspectives: Oxford university press.

Hendrischke, Hans J, & Feng, Chongyi. (1999). The political economy of China’s provinces: Comparative and competitive advantage: Psychology press.

Hessels, J., & Parker, S. C. (2013). Constraints, internationalization and growth: A cross-country analysis of European SMEs. Journal of World Business, 48(1), 137–148.

Ho, C.-T. B., Lenny Koh, S. C., Karaev, A., Lenny Koh, S. C., & Szamosi, L. T. (2007). The cluster approach and SME competitiveness: A review. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 18(7), 818–835.

Ikeme, J., & Ebohon, O. J. (2005). Nigeria's electric power sector reform: What should form the key objectives? Energy Policy, 33(9), 1213–1221.

Jerven, M. (2013). Comparability of GDP estimates in sub-Saharan Africa: The effect of revisions in sources and methods since structural adjustment. Review of Income and Wealth, 59(S1), S16–S36.

Kitching, Beverley, & Woldie, Atsese. (2004). Female entrepreneurs in transitional economies: A comparative study of businesswomen in Nigeria and China.

Knowledge, China). China cities economic data. Retrieved 25/05/2016, 2016a, from http://www.chinaknowledge.com/CityInfo/ranking.aspx?opt=gdp

Knowledge, China. (2016b). Major economic indicators, from http://www.chinaknowledge.com/CityInfo/City.aspx?Region=Coastal&City=Zhenjiang.

Laosirihongthong, T., Prajogo, D. I., & Adebanjo, D. (2014). The relationships between firm’s strategy, resources and innovation performance: Resources-based view perspective. Production Planning and Control, 25(15), 1231–1246.

Lechner, C., & Leyronas, C. (2012). The competitive advantage of cluster firms: The priority of regional network position over extra-regional networks–a study of a French high-tech cluster. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 24(5–6), 457–473.

Lee, S., Park, G., Yoon, B., & Park, J. (2010). Open innovation in SMEs-an intermediated network model. Research Policy, 39(2), 290–300.

Lee, H., Kelley, D., Lee, J., & Lee, S. (2012). SME survival: The impact of internationalization, technology resources, and alliances. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(1), 1–19.

Li, J., Yang, K., & Xu, Y. (2006). Regional differences in the development of Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(2), 174–184.

Library, O. E. C. D. (2012). Financing SMEs and Enterpreneurs., 2012 from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services/financing-smes-and-entrepreneurship_9789264166769-en.

Lindgren, R., Andersson, M., & Henfridsson, O. (2008). Multi-contextuality in boundary-spanning practices. Information Systems Journal, 18(6), 641–661.

Lonial, S. C., & Carter, R. E. (2015). The impact of organizational orientations on medium and small firm performance: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 94–113.

Lu, Y., Guo, H., Kao, E. H., & Fung, H.-G. (2015). Shadow banking and firm financing in China. International Review of Economics and Finance, 36, 40–53.

Meagher, Kate. (2013). Unlocking the informal economy: A literature review on linkages between formal and informal economies in developing countries. Work. ePap, 27.

Mesquita, L. F. (2016). Location and the global advantage of firms. Global Strategy Journal, 6(1), 3–12.

Mesquita, L. F., & Lazzarini, S. G. (2009). Horizontal and vertical relationships in developing economies: Implications for SMEs’ access to global markets new Frontiers in entrepreneurship (pp. 31–66). Berlin: Springer.

Mesquita, L. F., & Lazzarini, S. G. (2010). Horizontal and vertical relationships in developing economies: Implications for SMEs’ access to global markets new Frontiers in entrepreneurship (pp. 31–66). Berlin: Springer.

Miller, D., Xu, X., & Mehrotra, V. (2015). When is human capital a valuable resource? The performance effects of ivy league selection among celebrated CEOs. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 930–944.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People’s Republic of China (2015). China, Africa to strengthen industrial cooperation, from http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/zflt/eng/jlydh/t1277443.htm

National Bureau Of Statistics, Nigeria. (2010). National MSME collaboration survey. Nigeria: National Bureau Of Statistics from http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/pdfuploads/MSMES.pdf.

National household and informal sector survey. (2010). National household and informal sector survey, from www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/report/41.

North, D., & Smallbone, D. (2000). The innovativeness and growth of rural SMEs during the 1990s. Regional Studies, 34(2), 145–157.

Novakovic, D., & Huemer, C. (2014). A survey on business context intelligent computing, networking, and informatics (pp. 199–211). Berlin: Springer.

Office, Jiangsu Provincial Foreign Affairs. (2016). Jiangsu Cities. from http://www.jsfao.gov.cn/.

Ogunyomi, P., & Bruning, N. S. (2015). Human resource management and organizational performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Nigeria. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2015, 1–23.

Okwuosa, I., & Amaeshi, K. (2015). Responsible investment in Nigeria. The Routledge Handbook of Responsible Investment, 115.

Onokala, Uchechi, & Banwo, Adeleke. (2015). Informal sector in Nigeria through the lens of apprenticeship, education and unemployment.

Ozawa, Terutomo. (2015). Next great industrial transmigration: Relocating China’s factories to sub-Saharan Africa, flying-geese style?

Pigato, Miria, & Tang, Wenxia. (2015). China and Africa: Expanding economic ties in an evolving global context.

Porter, M. E. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: Local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14(1), 15–34.

Porter, M. E., & Clark, G. L. (2000). Locations, clusters, and company strategy. The Oxford handbook of economic geography, 2000, 253–274.

Porter, M. E., & Porter, M. P. (1998). Location, clusters, and the" new" microeconomics of competition. Business Economics, 1, 7–13.

Rauch, A., Doorn, R., & Hulsink, W. (2014). A qualitative approach to evidence-based entrepreneurship: Theoretical considerations and an example involving business clusters. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 333–368.

Renard, Mary-Françoise. (2011). China’s trade and FDI in Africa. African Development Bank Group working paper series, 126.

Shaw, J. D., Park, T.-Y., & Kim, E. (2013). A resource-based perspective on human capital losses, HRM investments, and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 34(5), 572–589.

Shen, Xiaofang. (2013). Private Chinese investment in Africa: Myths and realities. World Bank policy research working paper (6311).

Sonobe, Tetsushi, & Otsuka, Keijiro. (2016). Cluster-based industrial development: A comparative study of Asia and Africa: Springer.

Sorasalmi, T., & Tuovinen, J. (2016). Entering emerging markets: A dynamic framework dynamics in logistics (pp. 675–683). Berlin: Springer.

Stearns, T. M., Carter, N. M., Reynolds, P. D., & Williams, M. L. (1995). New firm survival: Industry, strategy, and location. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1), 23–42.

Tambunan, T. (2005). Promoting small and medium enterprises with a clustering approach: A policy experience from Indonesia. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(2), 138–154.

Today, China. (2016). China information and sources.

Usman, Z. G., Abbasoglu, S., Ersoy, N. T., & Fahrioglu, M. (2015). Transforming the Nigerian power sector for sustainable development. Energy Policy, 87, 429–437.

Wang, Y. (2004). Financing difficulties and structural characteristics of SMEs in China. China & World Economy, 12(2), 34–49.

Xue, C. L., & Rowley, C. (2007). Human resource management in Chinese small and medium enterprises: A review and research agenda. Personnel Review, 36(3), 415–439.

Yang, Y., Luo, H., & Law, R. (2014). Theoretical, empirical, and operational models in hotel location research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 209–220.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to anonymous reviewers and colleagues for their insightful comments, proofreading and constructive suggestions. This work supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2014S1A2A2027622), and supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants 71471076, 71171099, and 71201071, and by the Joint Research of The NSFC-NRF Scientific Cooperation Program under grant 71411170250. This work was also sponsored by Qing Lan Project and 333 Project of Jiangsu Province, and Jiangsu University Top Talents Training Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB designed the conceptual framework and carried some sections of the Literature studies, discussions as well as collating inputs of JU and UC. JU helped with literature, methods and data for China, UC provided the secondary data for Nigeria and conclusions. JU and UC reviewed the papers. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Banwo, A.O., Du, J. & Onokala, U. The determinants of location specific choice: small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries. J Glob Entrepr Res 7, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0074-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0074-2