Abstract

Over the last few years, the Federal Institute for material research (BAM, Berlin) together with the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC, University of Hamburg) have initiated a systematic material investigation of black inks produced from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages (ca. fourth century CE–fourteenth/fifteenth centuries CE), aimed primarily at extending and complementing findings from previous sporadic studies. Part of this systematic investigation has focused on Egyptian Coptic manuscripts, and the present preliminary study is one of its outputs. It centres on a corpus of 45 Coptic manuscripts—43 papyri and 2 ostraca—preserved at the Palau-Ribes and Roca-Puig collections in Barcelona. The manuscripts come from the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit, one of the largest monastic settlements in Egypt between the Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic Period (sixth–eighth centuries CE). The composition of their black inks was investigated in situ using near-infrared reflectography (NIRR) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF). The analyses determined that the manuscripts were written using different types of ink: pure carbon ink; carbon ink containing iron; mixed inks containing carbon, polyphenols and metallic elements; and iron-gall ink. The variety of inks used for the documentary texts seems to reflect the articulate administrative system of the monastery of Bawit. This study reveals that, in contrast to the documents, written mostly with carbon-based inks, literary biblical texts were written with iron-gall ink. The frequent reuse of papyrus paper for certain categories of documents may suggest that carbon-based inks were used for ephemeral manuscripts, since they were easy to erase by abrasion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although black inks have been used extensively across time and space to record information, the material investigation of their composition has often remained restricted to specific periods and geographical areas. However, in recent decades scholars in the humanities have shown an increasing interest in the materiality of inks as an inherent part of a physical manuscript. In response to this interest, in their modern editions of ancient texts, papyrologists have often included comments on the writing media used in the original codices, papyri and ostraca (fragments of pottery or limestone used to write on), relying only on visual observation to describe the colour, texture and state of preservation of the ink, along with codicological and bibliological aspects of the manuscripts (e.g. [1, 2]).

Over the last few decades, the Federal Institute for material research (BAM, Berlin), together with the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC, University of Hamburg), has embarked on a systematic archaeometric investigation aimed at collecting information on the material composition of black writing media produced before the Late Middle Age (ca. fourteenth/fifteenth century CE). This research has aimed to extend and complement findings from a handful of other material studies, which focused mostly on the composition of black Egyptian inks produced between Pharaonic times and the first centuries of the Common Era [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. One focus of this systematic investigation has been the analysis of inks from Egyptian Coptic manuscripts produced between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages (ca. fourth–eleventh centuries CE), which started in 2017 as a cooperation with the PAThs Project, based at La Sapienza University of Rome. Other publications resulting from this collaboration can be found in the list of references [14,15,16,17,18]. In parallel to this research, the BAM and CSMC developed further studies on Egyptian inks produced during the Hellenistic and Roman periods (e.g. [19, 20]). The present contribution is a direct output of the research on Coptic manuscripts, and focuses on the material analysis of writing media used towards the end of Late Antiquity (ca. seventh/eighth century CE) in the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit, one of the largest monastic complexes ever to have existed in Egypt.

The monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit: archaeological and historical contexts

The Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit is considered the most important monastery in Egypt in Late Antiquity (sixth–eighth centuries CE). It is located on the left bank of the Nile next to the modern village of Bawit—from which the site takes its name—25 km south of el-Ashmunein, in Middle Egypt, in the ancient nome of the Hermopolites [21, 22, p. 105 n. 1]. Scholars share the opinion that the monastery was founded by a monk named Apollo, who lived in the fourth century CE (Historia Monachorum in Aegypto 8) [2, p. 31–33, 36–41, 23, 24, p. 10–12]. However, so far the oldest archaeological levels excavated have been dated to the late sixth century CE [2, p. 46, 23, 25]. This date is confirmed by the oldest texts from the site [26, p. 133–175]. The monastery remained active into the Islamic Period (tenth–eleventh centuries CE): more recent texts (P.Mich. Copt. 21; P.Bawit Inv. 2003/1-EGN) and some architectural structures [25, p. 185] date from this time.

The archaeological site was discovered in 1900 and excavated first by the French Egyptologist Jean Clédat (1901–1905) [27] and later by Jean Maspero (1913). After that, the systematic excavation ceased and was restarted only in 2002 [28, 29]. The archaeological works brought to light a large monastic complex with three churches [30, p. 364–365, 31] and buildings from a male and a female community including monastic cells, urban architecture, industrial areas and two necropolises [2, p. 47–54, 25, p. 183–187]. These structures suggest that in Bawit there was a monastic village of considerable size [2, p. 45]. It is estimated that the monastery could have occupied some 40 ha of land [25]. If so, this would be one of the largest monastic sites in Egypt in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic Period (sixth–eighth centuries CE) [2, p. 55 n. 139, 32]. Literary and documentary texts seem to indicate that it may have hosted some 1000 inhabitants at some time between the seventh and eighth centuries [2, p. 54 n. 136].

The monastery of Apa Apollo seems to have been characterised by a system of self-efficiency. Its economy was very productive, consisting mainly of agriculture, farming and manufacturing activities [2, p. 74–108]. Goods for daily consumption and clothes were produced inside the village, therefore it is likely that writing materials (papyrus paper and/or ink) were also produced locally. Moreover, the monastery and monks also had currency [2, p. 241–259, 33, p. 23–27], meaning that anything the monastery was lacking could have been bought outside.

The papyrological texts from Bawit and those investigated at the Palau-Ribes and Roca-Puig collections

An enormous corpus of manuscripts has emerged from this monastic site. There are more than 700 published papyrological texts [26, p. 133–175], and the digital database Trismegistos has incorporated 1342 documents—including epigraphic texts—from the monastery [34]. The texts are written mostly on papyri and ostraca—pieces of pottery or limestone—in Greek, Coptic and Arabic, since the monastery was active from Byzantine times into the Islamic period. However, most of the manuscripts discovered so far are written in Coptic and can be dated to the seventh/eighth centuries CE.

Most of the known manuscripts from Bawit are documentary texts. The information they provide makes it possible to reconstruct the internal organisation and daily life of the monastery between the late Byzantine and early Islamic period (seventh/eighth centuries CE), when the site probably reached its peak. We have evidence of different types of documents, such as orders to supply goods, payments of salaries, accounts and lists, or even legal texts comprising loans, leases, sales and guarantees. These types of documents often show the use of well-established formulae, and reveal a structured and articulated internal administration [35, p. 104–105], which consisted probably of households hierarchically coordinated by a central institution [2, p. 65–74]. Finally, private relationships and networks are attested by letters. This rich production of documents indicates that the internal organisation system sought to record all the economic activities and business concerning the monastery. Therefore, it is likely that there existed a place, functioning as an archive, where these documents were stored [2, p. 70]. However, some types of documents such as invoices, receipts, accounts, lists or letters may have been kept only for as long as these activities were in effect. This would explain why the verso of existing documents was often reused; papyrus was very commonly recycled in Bawit [2, p. 76, 126, 165–166, 36, p. 10].

So far, the archaeological excavations have uncovered no evidence of a library preserving literary texts or a scriptorium dedicated to their production. However, it is very unlikely that this vast monastic complex was not equipped with such spaces [37, 38], as monastic settlements generally invested a great deal of effort in producing, preserving and transmitting literary religious texts. For the time being, the archaeological excavation at Bawit has brought to light only a few rather small literary fragments. Such is the case of a group of literary fragments, forming part of the same codex, found in 2017 [38]. It is plausible that some literary texts from Bawit were uncovered during illegal excavations and sold on the antiquities market, thus making it challenging to recognise their provenance. This seems to be the case of a miscellaneous codex (P.Cotsen-Princeton 1) whose place of discovery is unknown. Its linguistic features, together with an invocation to “Our Father Apa Apollo” written in the colophon, suggest that this codex may come from the monastery at Bawit [37, 39,40,41].

Historical inks: types and ingredients

Three primary types of ink are known to have been extensively used in historical manuscripts. Carbon ink is a suspension of soot or charcoal particles, derived from a variety of animal or vegetal precursors, in a water-soluble binder. Plant ink is a solution of vegetable extracts obtained after cooking bark, gall nuts or other vegetal matter, producing a mixture of polyphenols. Iron-gall ink has been historically prepared mixing three main ingredients: vitriol (a mixture of metallic sulphates in different proportions, containing mainly iron, copper and, in some cases, zinc [42]), gall nut extracts, and gum arabic [43]. It is worth pointing out that in the last 20 years, the conservation community has been considering iron-gall ink as a suspension of iron-gallate pigment, obtained from the reaction of bivalent iron from vitriol with gallic acid from gall nuts [44,45,46]. However, a recent study showed that the composition of gall nut extracts is more complex than previously assumed. Depending on the extraction method used, gallic acid can be a minor compound compared to its derivatives (in the form of polygalloyl esters of glucose), suggesting that iron might bind with other polyphenols as well [47,48,49]. Ink mixtures deriving from different combinations of these three primary types of ink, or obtained by adding metallic salts to soot and charcoal, are also documented, and have recently received increasing scientific attention. The difficulties encountered in analytically identifying mixed inks are the subject of a recent article [50].

Material investigations of historical inks revealed the use of carbon-based inks as far back as the Pharaonic period [4, 7, 13, 51]. A recipe for this type of ink appears in a papyrus with the Book of the Dead (the Yuya papyrus: pKairo CG 51189) [52], and several recipes are found in the corpus of Papyri Grecae Magicae, dated from the Roman period onwards [53]. Outside of Egypt, carbon ink is mentioned in Vitruvius and Pliny’s treatises [54, p. 290–293, 55, p. 33–34]. By contrast, the material investigation of Egyptian manuscripts has yet to yield any evidence of plant ink. A recipe mentioning this type of ink is recorded in a treatise by Martianus Capella, a Latin prose writer from the fifth century CE [56, p. 225], and other recipes are found in medieval Arabic treatises [57, p. 122–125]. At a certain point in time, iron-gall ink was introduced. To our best knowledge, the earliest recipe of this type of ink is probably reported in a papyrus from the third century CE [58, p. 83]. However, terminological issues regarding the ingredients mentioned hamper the unequivocal interpretation of this text. Material analysis of Egyptian inks has found evidence of iron-gall ink from the fourth century onwards [14, 16, 17]. Therefore, this type of ink was already in use in Egypt during the period of prosperity of the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit, when the manuscripts presented in this study were written.

Mixed inks frequently appear in Arabic recipes. Interestingly, a mixed ink of the type carbon plus iron-gall is described under the name “Egyptian ink” in two copies of the treatise on the arts of the book, Umdat al-kuttāb, by ibn Bādīs (d. 454 AH/1062 CE) [57, n. 101, 59, formula 174]. The original treatise dates from the eighth century CE, being coeval with the manuscripts from Bawit, and is based on earlier sources. However, it was not uncommon for the compiler of a treatise’s copy to change the existing text or add new recipes, thus making it difficult to date them. Furthermore, an ink containing carbon and the copper-based compound chalkanthon (χάλκανθον, whose composition in Antiquity evades identification) is described in the treatise by Dioscorides [60: book 5, p. 114, 183]. Recent archaeometric analyses performed on different collections of Egyptian papyri have revealed inks containing carbon particles and metallic elements (Cu, Fe, Pb) [3,4,5,6, 10, 19, 20, 51]. For the most part, the origin of these metals remains an open question since the metal-containing compounds could not be identified, and their presence in inks could have resulted from several processes. However, synchrotron-based microanalysis recently suggested that lead-based compounds might have been intentionally added as a drying agent to the ink of a corpus of manuscripts from the Roman period [5]. On the other hand, a similar investigation of some Greco-Roman papyrus fragments seems to indicate that copper was present as a by-product in the soot used to prepare the ink [10]. In a different scenario, metallic tools and vessels used during manufacturing, storage and writing may have contaminated the ink. However, scarce information is available on tools explicitly used during these processes. Interestingly, the Morgan Library and Museum preserves a wooden box with a sliding cover and a shallow cavity for a removable metal inkwell dated to the Coptic period [61, p. 601].

Materials and methods

Description of the manuscripts and analytical protocol

During this preliminary study, we analysed a group of 45 Coptic texts. The texts date from between the seventh and eighth centuries CE, and correspond mainly to fragmentary texts written mostly on papyrus, although two ostraca were investigated as well. Thirty-seven texts are preserved at the Palau-Ribes Collection and eight at the Roca-Puig Collection. These two collections house Greek and Coptic texts from the monastery of Apa Apollo. They were purchased on the antiquities market by the priest Ramon Roca-Puig (1906–2001), who acquired the Roca-Puig Collection in the 1950s, and the Jesuit José O’Callaghan (1922–2001), who acquired the Palau-Ribes Collection in the 1960s. Unfortunately, little information is available about the provenance and acquisition process of the manuscripts they purchased. Of the 45 manuscripts investigated, 42–40 papyri and 2 ostraca—are documentary texts of different typologies. They include economic documents such as accounts, lists, orders and receipts of payment, legal texts, and private letters. Some of these documents have been reused one or more times. They were identified as proceeding from Bawit by comparing their formats, scripts and recurring textual formulas with those of the documents found during the archaeological excavations at the beginning of the 1900s. Furthermore, this investigation includes three literary fragments with New Testament texts (P.PalauRibes Inv. 90, Inv. 134 and Inv. 427). Recently, Anne Boud’hors compared the palaeographical and codicological features of these fragments with those of the literary codex found during the excavation at Bawit in 2017, concluding that they are very similar. This similarity may indicate that the New Testament fragments come from Bawit [38]. However, further investigation is needed to confirm this attribution.

The manuscripts were analysed on-site at the two collections using a two-step analytical protocol for ink analysis introduced by Rabin et al. [62]. A first screening was carried out using near infrared reflectography (NIRR)—and occasionally ultraviolet reflected photography (UVR)—to observe the visual appearance of the inks under different lighting conditions. Then, the elemental composition of the inks and supports was investigated using X-ray fluorescence (XRF). The manuscripts were initially preserved in folders made of blotting paper and stored in organised drawers. Before proceeding to the analysis, the texts were positioned on a clean glass used as a support to handle them, to reduce their physical stress while moving them around. The supporting glass did not contain any consistent amounts of iron, copper or lead that could have significantly interfered with qualitative XRF analysis (Additional file 1).

Not all the manuscripts were available to be investigated both with NIRR and XRF. Table 1 reports the list of the texts studied along with the methods applied to each. NIRR was used to observe the ink exclusively, as it does not provide any insight into the composition of the supports investigated. Instead, XRF was applied both to inked and non-inked spots (ink and support). The support was measured close to the inked spot analysed in an attempt to compensate for the heterogeneity of the papyrus paper, particularly in the spatial distribution of iron [16], which can represent a challenge when evaluating the results.

Near-infrared and ultraviolet reflected photography (NIRR and UVR)

A DinoLite AD4113T-I2V USB microscope was used to observe the manuscripts under different lighting conditions. This small portable device is equipped with three light sources: near-infrared (940 nm), UV (395 nm), and an external white LED light to increase the illumination of visible photographs. The micro-photographs were captured at 50× magnification.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF)

An Elio Bruker Nano GmbH (formerly XG Lab) was used for XRF analysis. This X-ray spectrometer features a 4-W low-power Rhodium tube, adjustable excitation parameters and a 25-mm2 SDD detector with energy resolution < 140 eV for Mn Kα. The beam size is ca. 1 mm and the analytical lower limit is Z ≥ 11. The measurements were acquired in ambient atmosphere on single spots, setting excitation parameters at 40 kV and 80 μA, with an acquisition time of 2 min per spot. Peak-fitting and data evaluation were conducted using Bruker’s SPEKTRA software.

Preparation of a mock-up sample of plant ink

Plant ink was obtained from gall nuts that were crushed and boiled in water for approximately one hour to extract the polyphenols. The liquid obtained was filtered, and gum arabic was added. The mixture was left to cool and then used to prepare the samples.

Results

Documentary texts

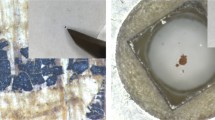

Twenty texts were investigated solely using NIRR (O.PalauRib. Inv. 25 and 26; P.PalauRib. Inv. 37, 41, 87, 352, 360, 384r, 390, 392, 393, 404, 409, 411, 433v, 434, 438r, 438v, 439 and 443). In all cases, this method showed that the inks are carbon-based. Figure 1 shows the comparison of visible and near-infrared (940 nm) images of inked areas of P.PalauRib. Inv. 41 and 360. In both cases, the ink shows no change in opacity between visible and near-infrared light, as is typical for carbon particles [63, 64]. By contrast, at this infrared wavelength iron-gall ink would change its opacity but remain partly visible [63, 64, 65, Figure 3], and plant ink would disappear completely [63, 64].

The remaining 22 documents were analysed both with XRF and NIRR. The combination of these methods allowed a more thorough investigation and showed the use of different inks. A group of 8 texts (P.PalauRib. Inv. 367, 376v, 406r, 454 and 460; P.Monts.Roca Inv. 521, 570 and 715) had been written with pure carbon ink. Figure 2 shows the ink of P.PalauRib. 460. No change in opacity is observed when comparing the visible and near-infrared micro-photograph, revealing carbon particles [63, 64]. The XRF spectra were acquired on two regions of the document. Per each region, an inked spot and a papyrus spot were measured. The comparison of XRF spectra obtained on ink and papyrus in region 1 shows that their profiles match, indicating that no element is associated with the ink exclusively. Similarly, no element is correlated with the ink measured in region 2. In this case, the intensity of iron in the support is higher than in the inked spot and much higher than the intensity of iron measured in the support in region 1. This heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of iron was previously observed while applying XRF to ancient papyrus, and the limitations it imposes on the application of the in-situ analytical protocol used in this study were discussed in a different work [16]. Furthermore, a recent investigation using synchrotron-based techniques produced two-dimensional and three-dimensional chemical maps showing that iron is present in micrometre-sized clusters at the surface of the papyrus [4]. Whether this results from manufacturing processes or later environmental pollution remains presently unclear.

Inks containing carbon and iron were found on 6 documents (P.PalauRib. Inv. 39, 40 and 354; P.Monts.Roca Inv. 557, 636 and 670). As already mentioned, the presence of iron and other metals in carbon inks could be the result of several processes. Aside from an intentional addition of ingredients containing metals, metallic tools and vessels used during manufacturing, storage and writing may have contaminated the ink. Alternatively, metals could be present as a by-product of the carbon particles used to prepare the writing medium. The analysis performed during this preliminary study offered little help to determine whether ingredients containing iron were added intentionally to the ink of these 6 papyri. Since no molecular analysis was performed, the chemical compound(s) containing iron could not be identified. Therefore, the comparison of XRF intensities of the metals measured in inked and non-inked spots was the only tool that could provide some insight: the presence of substantial amounts of iron in the ink would suggest it was added intentionally, rather than deriving from contamination. However, since the spatial distribution of iron in the papyrus support of these documents is very heterogeneous, it becomes challenging to establish the XRF intensity of iron correlated with the ink, particularly because only a limited number of spots per manuscript were investigated.

For instance, Fig. 3 shows the case of P.Monts.Roca Inv. 636. Once again, the comparison of visible and near-infrared micro-photographs does not show a change in opacity, indicating the presence of carbon [63, 64]. Moreover, the comparison of XRF spectra of inked and non-inked spots in region 1 shows that a higher intensity of iron is measured in the ink. Finally, the bar graph reports the net peak areas for iron measured in the support and inked spots on three different regions of the document. In all cases, the contribution of iron measured in the inked spot is higher than in the support. However, in region 1 the net peak area for iron in the ink is roughly double than in the support, in region 2 it is only about 20% greater and in region 3 about 30% greater. Therefore, no conclusion will be forced on the nature of these inks until further studies on a higher number of spots will be carried out, or the application of other analytical methods will provide a deeper understanding of the nature of the iron-containing compounds.

P.Monts.Roca 636. Top left: the white frames highlight the three regions investigated (R1, R2 and R3). Top right: visible and NIR micro-photographs (magnification: ×50) of R1. Bottom right: XRF spectra of inked and non-inked spots from R1. Bottom right: XRF raw net peak areas of Fe measured on inked and non-inked spots in R1, R2 and R3

In four cases, the combination of NIRR and XRF revealed the use of mixed inks (P.PalauRib. Inv. 371 and 402; P.Monts.Roca Inv. 227 and 345). Figure 4 shows P.Monts.Roca Inv. 227 and Inv. 345, together with a mock-up sample of plant ink. In these cases, not just NIR but also UV light provides valuable insight into the composition of these inks. Figure 4 shows that the mock-up sample of plant ink becomes transparent at 940 nm and appears dark under UV light (395 nm) since the phenolic rings of polyphenols absorb UV light [66]. The image acquired in visible light on P.Monts.Roca Inv. 227 and Inv. 345 shows a black trace of ink surrounded by a brownish halo. The black trace of ink does not change its opacity in the near-infrared light, revealing carbon [63, 64]. Besides, the brownish halo around the ink disappears at 940 nm and becomes dark under UV light, as is typical of plant ink. This suggests that the ink of these four papyri was prepared by mixing carbon and polyphenols. In a previous publication, we addressed mixed inks explaining that NIRR is, in some cases, insufficient to identify them as it might reveal only the main component in a mixture [50]. However, the visual appearance of the inks on these four papyri allows discriminating the black trace of ink from the brownish halo. Therefore, both these regions can be observed under NIR and UV light to characterise the different components of the inks.

Furthermore, XRF analysis detected the consistent presence of metals, confirming that these four papyri had been inscribed using mixed inks. Figure 5 shows the net peak areas measured for iron (blue), copper (green) and lead (red) on three different inked spots for each one of the four manuscripts. The grey bars represent the intensity of the elements in the support measured close to each inked spot; so the intensity of the element associated with the ink can be seen by looking at the height by which the coloured column extends beyond its associated grey column.

XRF raw net peak intensities of Fe, Cu and Pb measured in three different regions (1, 2, 3) on each manuscript: P.Monts.Roca Inv. 227 and Inv. 345; P.PalauRib. Inv. 371 and Inv. 402. This graph reports qualitative results only since the cross-section of the interaction between the element and the X-rays grows with the atomic number

The presence of both iron and copper in the inks from these four papyri suggests the use of vitriol. This ingredient was historically mixed with polyphenols extracted from gall nuts to make iron-gall ink. Therefore, it is likely that these inks were originally prepared by mixing carbon and iron-gall ink. However, to our best knowledge, lead has never been reported as a component of vitriol. Thus, its presence in the inks has probably a different origin. As previously discussed, lead was sometimes detected during the analysis of carbon inks [5, 6, 67], and a recent study suggested lead-based compounds might have been used as drying agents in the preparation of inks [5].

Finally, NIRR did not lead to conclusive results in the case of P.PalauRib. Inv. 357, Inv. 399, Inv. 401 and Inv. 451v. Figure 6 shows P.PalauRib. Inv. 357 and 451v. In both cases, the ink shows a heterogeneous change in opacity when illuminated with near-infrared light. For Inv. 357, this is particularly visible on the letter “K”, which appears darker and more substantial on its right and lighter and more meagre on the left. In contrast, the letter on the right maintains its opacity. Similarly, the ink on Inv. 451v remains more opaque on the left and top of the letter “a” and fades in correspondence with the letter “y”.

On these four documents, XRF detected iron, copper and, in the case of P.PalauRib. Inv. 357, lead (Fig. 7). These metals recall those found on the papyri from the previous group and may hint at the original material composition of these inks, suggesting that they were initially similar to the mixed inks presented above. If that were the case, the handling of the manuscripts over centuries together with the ageing process of the ink might have caused the loss of carbon particles originally sitting on the surface. This loss of material would prevent NIRR from detecting it. In these cases, Raman spectroscopy could be applied to gain further insight into the inks on these four papyri. Because carbon presents a strong Raman fingerprint, this technique has been frequently applied to the study of inks [68,69,70,71].

XRF raw net peak intensities of Fe, Cu and Pb measured in three different regions (1, 2, 3) on each manuscript: P.PalauRib. Inv. 357, Inv. 399, Inv. 401 and Inv. 451v. This graph reports qualitative results only since the cross-section of the interaction between the element and the X-rays grows with the atomic number

Literary fragments

The literary fragments were investigated solely using near-infrared reflectography. Although it was not possible to collect information on their elemental composition, the results from NIRR are rather interesting. Figure 8 shows the visible and near-infrared micro-photographs of one inked area on each of the fragments. The ink’s opacity changes considerably in the infrared region, which is typical of iron-gall ink [63, 64, 65, Figure 3]. This type of ink was never observed on the documentary texts analysed.

Discussion

The results obtained on the documentary texts indicate that at least two types of ink—pure carbon ink and mixed ink containing carbon, polyphenols and metals—were used to write the documentary papyri at the monastery of Bawit. Considering that lead was not found in all of the mixed inks analysed, and that a group of inks containing carbon and iron still awaits a detailed material characterisation, it is likely that the scribes working in the offices of the monastery used further types of inks. This variety of writing media seems to reflect the articulate administrative system of the large monastic settlement of Bawit: it is plausible that different offices, or different scribes, used distinct types of ink.

In contrast to the inks used for the documents, the three literary fragments investigated were written using iron-gall ink. In our past studies, we observed a tendency to use mostly inks containing carbon for documentary texts and iron-gall ink for literary texts in manuscripts produced in various areas of Egypt dating between the second and eighth century CE [16]. If we accept the attribution of these three New Testament literary fragments to the monastery of Bawit, the manuscripts investigated show that this tradition of different inks for different genres holds even within a single institution. Since only three literary fragments were investigated versus more than 40 documents, further evidence is needed to support this finding. However, these results invite further reflection on the reasons behind this tradition.

Economic factors must have influenced the choice of writing materials. However, any discussion of the price of the various inks is unfortunately precluded by the lack of available information. A document from Tebtunis from the 45 CE (P.Mich. 2 123v) [72] and the Edict of Diocletian dated to the 301 CE report the price tags for inks and writing materials [73, p. 388, 74, p. 151]. In both texts, the term ink (Greek μέλαν, Latin atramentum) is used without any specification on its material composition. Therefore, without further information from historical sources, it is difficult to guess whether iron-gall ink was more or less expensive than carbon ink. In fact, Pliny mentions the existence of different qualities of carbon ink: soot was obtained by burning different precursors such as pine logs or ivory, so the resulting inks most likely came with different price tags [54, p. 290–293]. We already suggested that the material characteristics of carbon and iron-gall may have affected the choice of ink as well [16]. In fact, abrasion and water sensitivity tests showed that carbon ink is very easy to erase, while iron-gall ink is more enduring and requires a specific acidic treatment [75]. On this matter, it is interesting to note that the reuse of documentary papyri in the monastery of Bawit is well attested; in many cases the papyrus support was used to write a second text. In her study on orders of payment from the Monastery of Bawit, Sarah Clackson points out that many showed signs of reuse [36, p. 10]. Similarly, Alain Delattre points out that two-thirds of the documentary texts classified as orders of payment from Bawit and preserved at the Musées royaux d’art et d’histoire in Brussels were reused. Sometimes the papyrus was reused multiple times, as in the case of P.Brux. Inv. E 9445v (=P.Brux.Bawit 11), an order of payment for oil. Here, the papyrus paper was used on both sides to write two texts at different times. Then, one side was cleared before writing a third text, although traces of the second text are still visible (palimpsest) [2, p. 126, 165–166]. Delattre thinks that the administrative office in charge of the orders of payment was equipped to “wash” the papyri to reuse the writing support: “The administrative office which issued the orders of payment cut up used papyrus leaves, sometimes washed them and reused them to note the orders of payment.” [2, p. 165–166]. The orders of payment preserved at the Palau-Ribes collection confirm this trend. For instance, P.PalauRib. Inv. 433v and Inv. 451v were reused multiple times: traces of ink from a previous washed text are visible, and an even older text is preserved on the other side. P.PalauRib. Inv. 401 presents some traces of ink unconnected to the text, probably belonging to an earlier text that was washed away. Similarly, P.PalauRib. Inv. 40 and Inv. 352 both reveal traces of a previously erased text, as shown in Fig. 9. Furthermore, the writing surface of Inv. 352 was reinforced in several areas with additional papyrus strips, probably to offset damage due to washing.

The extensive reuse of the support suggests that the orders of payment were perceived as ephemeral manuscripts, whose content could be erased once their purpose had been fulfilled. A future systematic study of the inks used on ephemeral and enduring documentary texts could provide further insight into whether carbon-based inks may have been chosen for ephemeral documentary manuscripts in order to easily erase the text once it had lost its value, much like the modern choice to use a pencil instead of a pen.

Conclusions

The systematic investigation of 45 manuscripts from the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit revealed that the texts were written using a variety of inks, namely: carbon ink, mixed inks with different elemental compositions, carbon inks containing iron whose material composition should be further investigated, and iron-gall ink. The variety of inks found is not surprising, since this monastic settlement was one of the largest in Egypt, and its administrative system was very articulate.

This study points to a tendency to use carbon-based inks for documentary texts and iron-gall inks for literary biblical works, although further historical studies are needed in order to confirm that the literary fragments investigated were indeed produced at Bawit. This same trend had been previously observed on documentary and literary manuscripts produced in various areas of Egypt between the second and eighth century CE [16]. At present we can only speculate as to the reasons behind these material differences, but further analysis of the Bawit manuscripts will hopefully shed light on the matter. The fact that at the Monastery of Apa Apollo the papyrus support of certain categories of documents was often reused—with particular reference to the orders of payment—may suggest that within this institution ephemeral texts were written using carbon-based inks because they were easier to erase. To confirm this hypothesis, a systematic material investigation should address, on the one hand, ephemeral and enduring documentary texts and, on the other, literary biblical works.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FTIR:

-

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- NIRR:

-

Near-infrared reflectography

- NIR:

-

Near-infrared

- UV:

-

Ultraviolet

- VIS:

-

Visible

- XRF:

-

X-ray fluorescence

References

Albarrán Martínez MJ, Boud’hors A, Delattre A, editors. Coptica Barcinonensia. Textes et documents de la 5e université d’été de papyrologie copte. Leuven: Peeters. J Copt Stud; 2017.

Delattre A. Papyrus coptes et grecs du monastère d’Apa Apollô de Baouît conservés aux Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire de Bruxelles. Brussels: Académie Royale de Belgique; 2007. (Mémoires de la Classe des Lettres).

Pereira FJ, Lopez R, Brasas M, Alvarez R, Aller AJ. Synergism between SEM/EDX microanalysis and multivariate analysis for a suitable classification of Roman and Byzantine papyri. Microchem J. 2021;160:105688.

Autran P-O, Dejoie C, Hodeau J-L, Dugand C, Gervason M, Anne M, et al. Revealing the nature of black pigments used on ancient Egyptian papyri from Champollion collection. Anal Chem. 2021;93:1135–42.

Christiansen T, Cotte M, de Nolf W, Mouro E, Reyes-Herrera J, de Meyer S, et al. Insights into the composition of ancient Egyptian red and black inks on papyri achieved by synchrotron-based microanalyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(45):27825–35.

Chiappe C, Pomelli CS, Sartini S. Combined use of scanning electron microscopy–energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and Fourier transform infrared imaging coupled with principal component analysis in the study of ancient Egyptian papyri. ACS Omega. 2019;4(26):22041–7.

Festa G, Christiansen T, Turina V, Borla M, Kelleher J, Arcidiacono L, et al. Egyptian metallic inks on textiles from the 15th century BCE unravelled by non-invasive techniques and chemometric analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7310.

Arlt T, Mahnke H-E, Siopi T, Menei E, Aibéo C, Pausewein R-R, et al. Absorption edge sensitive radiography and tomography of Egyptian papyri. J Cult Herit. 2019;39:13–20.

Rabin I, Krutzsch M. The writing surface papyrus and its materials 1. Can the writing material papyrus tell us where it was produced? 2. Material study of the inks. In: Proceedings of the 28th congress of papyrology, 2016 August 1–6; Barcelona Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, Universitat Pompeu Fabra; 2019 p 773–781. Publicacions Abadia de Montserrat; 2019. p. 773–81.

Christiansen T, Cotte M, Loredo-Portales R, Lindelof PE, Mortensen K, Ryholt K, et al. The nature of ancient Egyptian copper-containing carbon inks is revealed by synchrotron radiation based X-ray microscopy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15346.

Macarthur D. AGLAE et l’étude des encres et des colorants de manuscrits. Techne. 1995;2:68–75.

Delange E, Grange M, Kusko B, Menei E. Apparition de l’encre métallogallique en Égypte à partir de la collection de papyrus du Louvre. Rev DÉgyptologie. 1990;41:213–7.

Lucas A. The inks of ancient and modern Egypt. Analyst. 1922;47(550):9–15.

Ghigo T, Bonnerot O, Buzi P, Krutzsch M, Hahn O, Rabin I. An attempt at a systematic study of inks from Coptic manuscripts. Manuscr Cult. 2018;11:157–64.

Ghigo T, Rabin I. Archaeometric study of inks from Coptic manuscripts in the collection of the Apostolic Vatican Library. In: Buzi P, editor. Detecting early Mediaeval Coptic literature in Dayr al-Anbā Maqār, between textual conservation and literary rearrangement: the case of Vat Copt 57. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana; 2019. p. 77–83. (Studi e Testi).

Ghigo T, Rabin I, Buzi P. Black Egyptian inks in late antiquity: new insights on their manufacture and use. J Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2020;12:70.

Ghigo T, Torallas Tovar S. Between literary and documentary practices: the Montserrat Codex Miscellaneus (Inv. Nos. 126–178, 292, 338) and the material investigation of its inks. In: Buzi P, editor. Coptic literature in context the contexts of Coptic literature. Rome: Quasar; 2020. p. 101–14.

Ghigo T, Rabin I. Gaining perspective into the materiality of manuscripts: the contribution of archaeometry to the study of the inks from the White Monastery codices. In: Buzi P, editor. Coptic literature in context the contexts of Coptic literature. Rome: Quasar; 2020. p. 273–81.

Rabin I, Wintermann C, Hahn O. Ink characterisation performed in Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (September 2018). Analecta Papyrol. 2019;31:301–13.

Nehring G, Bonnerot O, Gerhardt M, Krutzsch M, Rabin I. Looking for the missing link in the evolution of black inks. Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2021;13(4):71.

TM Geo 10454. https://www.trismegistos.org/place/10454. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Clédat J. Le monastère et la nécropole de Baouît. Tome I. Le Caire: IFAO (MIFAO); 1904.

La TH. date de la fondation du monastère d’Apa Apollô de Baouît et de son abandon. Mélanges D’archéologie D’histoire. 1965;77:153–77.

Torp H. The laura of Apa Apollo at Bawit. Considerations on the founder’s monastic ideals and the South Church. Arte Mediev. 2006;2:9–46.

Herbich T, Bénazeth D. Le kôm de Baouît: étapes d’une cartographie. Bull Inst Fr Archéologie Orient. 2008;108:165–204.

Clackson S, Delattre A. Papyrus grecs et coptes de Baouît conservés au musée du Louvre. Le Caire: IFAO; 2014. (Bibliothèque d’Études coptes 22).

Clédat J. Notes archéologiques et philologiques. Bull L’Institut Fr D’Archéologie Orient. 1901;1:87–97.

Bénazeth D. Histoire des fouilles de Baouît. In: Rosenstiehl JM, editor. Études coptes IV. Strasbourg: Éditions Peeters; 1995. p. 53–62. (Cahiers de la Bibliotheque Copte 8).

Bénazeth D. Recherches archéologiques à Baouit: un nouveau départ. Bull Société Archéologie Copte. 2004;43:9–24.

Coquin RG, Martin M, Severin HG, Du Burguet P, Bawit. Archaeology, architecture, and sculpture; and paintings. In: Atiya AS, editor. The Coptic encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan; 1999.

Hadji-Minaglou G. Le site monastique de Baouît et son église principale: état des lieux à l’issue de la dernière campagne de fouilles. In: Boud’hors A, Louis C, editors. Études coptes XIV Seizième journée d’études, Genève, 19–21 juin 2013. Paris: Brepols; 2016. p. 47–62.

Grossmann P. Ruinen des Klosters Dair al-Balaiza in Oberägypten: eine Surveyaufnahme. Jahrb Für Antike Christ. 1993;36:173–205.

Clackson S. Coptic and Greek texts relating to the Hermopolite monastery of Apa Apollo. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum; 2000.

Trismegistos. https://www.trismegistos.org/tm/. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Albarrán Martínez MJ, Boud’hors A. À la découverte des papyrus coptes de la Sorbonne. In: Boud’hors A, Louis C, editors. Etudes coptes XIV. Geneva: Brepols Publishers; 2016. p. 101–14. (Études d’archéologie et d’histoire ancienne).

Clackson SJ. It is our Father who writes: orders from the Monastery of Apollo at Bawit. Cincinnatti: American Society of Papyrologists; 2008.

Delattre A. Intellectual life in Middle Egypt: the case of the Monastery of Bawit. In: Gabra G, Takla H, editors. Christianity and Monasticism in Middle Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press; 2015.

Boud’hors A. Réflexions sur les Conditions d’Existence d’une Bibliothèque à Baouit. In: Calament F, Hadji-Minaglou G, editors. Baouit. Le Caire: IFAO (in press).

Bucking S. A Sahidic Coptic manuscript in the private collection of Lloyd E. Cotsen (P. Cotsen 1) and the limits of papyrological interpretation. J Copt Stud. 2006;8:55–78.

Bucking S. Practice makes perfect: P. Cotsen-Princeton 1 and the training of scribes in Byzantine Egypt. Los Angeles: Cotsen Occasional Press; 2011.

TM Texts 105708. https://www.trismegistos.org/text/105708. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Karpenko V, Norris JA. Vitriol in the history of chemistry. Chem Listy. 2002;96:997–1005.

Stijnman A. Iron gall inks in history: ingredients and production. Iron Gall Inks Manuf Characterisation Degrad Stab Natl Univ Libr Ljubl. 2006;25–68.

Wunderlich C-H. Geschichte und Chemie der Eisengallustinte: Rezepte. Reaktionen und Schadwirkungen Restauro. 1994;100(6):414–21.

Krekel C. The chemistry of historical iron gall inks: understanding the chemistry of writing inks used to prepare historical documents. Int J Forensic Doc Exam. 1999;5:54–8.

Ponce A, Brostoff LB, Gibbons SK, Zavalij P, Viragh C, Hooper J, et al. Elucidation of the Fe(III) Gallate structure in historical iron gall ink. Anal Chem. 2016;88(10):5152–8.

Wagner FE, Lerf A. Mössbauer spectroscopic investigation of FeII and FeIII 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoates (Gallates)—proposed model compounds for iron-gall inks. Z Für Anorg Allg Chem. 2015;641(14):2384–91.

Lerf A, Wagner FE. Model compounds of iron gall inks—a Mössbauer study. Hyperfine Interact. 2016;237(1):36.

Díaz Hidalgo RJ, Córdoba R, Nabais P, Silva V, Melo MJ, Pina F, et al. New insights into iron-gall inks through the use of historically accurate reconstructions. Herit Sci. 2018;6:63.

Colini C, Hahn O, Bonnerot O, Steger S, Cohen Z, Ghigo T, et al. The quest for the mixed inks. Manuscr Cult. 2018;11:41–9.

Christiansen T, Buti D, Dalby KN, Lindelof PE, Ryholt K, Vila A. Chemical characterization of black and red inks inscribed on ancient Egyptian papyri: the Tebtunis temple library. J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2017;14:208–19.

Tatomir R. To cause “to make divine” through smoke: ancient Egyptian incense and perfume. An inter- and transdisciplinary re-evaluation of aromatic biotic materials used by the ancient Egyptians. In: Panaite A, Cîrjan R, Cǎpiţǎ C, editors. Moesica et Christiana— Studies in honor of Professor Alexandru Barnea. Editura Istros. Braila; 2016. p. 665–78.

Christiansen T. Manufacture of black ink in the ancient Mediterranean. Bull Am Soc Papyrol. 2017;54:167–95.

Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia, XXXV.25. Rackham H, editor. Natural history, volume IX: Books 33–35. Loeb classical library, 394. Cambridge: Massachusetts Harvard University Press; 1961.

Vitruvius. De Architectura, VII.10. Cam M-Th, Liou B, Zuinghedau M, editors. De l’Architecture. Livre VII. Paris: Les Belles Lettres; 1995.

Capellae M. De nuptiis philologiae et mercurii. Vol. III. https://ia802708.us.archive.org/1/items/denuptiisphilolo00martuoft/denuptiisphilolo00martuoft.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Schopen A. Tinten und Tuschen des arabisch-islamischen Mittelalters: Dokumentation, Analyse, Rekonstruktion: ein Beitrag zur materiellen Kultur des vorderen Orients. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2006.

Preisendanz K. Papyri Graecae magicae. Die Griechischen Zauberpapyri, herausgegeben und übersetzt von Karl Preisendanz, vol. 2. Berlin: Teubner; 1931.

Colini C. From recipes to material analysis the Arabic tradition of black inks and paper coatings (9th–20th century), Ph.D. Thesis. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg; 2018.

Dioscorides Pedanius. De materia medica. Being an herbal with many other medicinal materials, written in Greek in the first century of the common era: a new indexed version in modern English, vol. V. Johannesburg: IBIDIS; 2000.

Depuydt L, Loggie DA. Catalogue of Coptic manuscripts in the Pierpont Morgan library, vol. 2. Louvain: Peeters; 1993.

Rabin I, Schütz R, Kohl A, Wolff T, Tagle R, Simone P, et al. Identification and classification of historical writing inks in spectroscopy: a methodological overview. Comp Orient Manuscr Stud Newsl. 2012;3:26–30.

Mrusek R, Fuchs R, Oltrogge D. Spektrale Fenster zur Vergangenheit: Ein neues Reflektographieverfahren zur Untersuchung von Buchmalerei und historischem Schriftgut. Naturwissenschaften. 1995;82(2):68–79.

Rabin I, Binetti M. NIR reflectography reveals ink type: pilot study of 12 Armenian manuscripts of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Banber Matenad. 2014;21:465–70.

Aceto M, Agostino A, Fenoglio G, Idone A, Gulmini M, Picollo M, et al. Characterisation of colourants on illuminated manuscripts by portable fibre optic UV–visible–NIR reflectance spectrophotometry. Anal Methods. 2014;6(5):1488–500.

Aleixandre-Tudo JL, du Toit W. The role of UV–visible spectroscopy for phenolic compounds quantification in winemaking. Front New Trends Sci Fermented Food Beverages. IntechOpen; 2018. https://www.intechopen.com/books/frontiers-and-new-trends-in-the-science-of-fermented-food-and-beverages/the-role-of-uv-visible-spectroscopy-for-phenolic-compounds-quantification-in-winemaking. Accessed 12 May 2021.

Brun E, Cotte M, Wright J, Ruat M, Tack P, Vincze L, et al. Revealing metallic ink in Herculaneum papyri. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(14):3751–4.

Edwards HGM. Analytical Raman spectroscopy of inks. In: Raman spectroscopy in archaeology and art history. 2018. p. 1–15. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/chapterhtml/2018/bk9781788011389-00001?isbn=978-1-78801-138-9.

Goler S, Hagadorn A, Ratzan DM, Bagnall R, Cacciola A, McInerney J, et al. Using Raman spectroscopy to estimate the dates of carbon-based inks from ancient Egypt. J Cult Herit. 2018;38:106–17.

Goler S, Yardley JT, Cacciola A, Hagadorn A, Ratzan D, Bagnall R. Characterizing the age of ancient Egyptian manuscripts through micro-Raman spectroscopy. J Raman Spectrosc. 2016;47(10):1185–93.

Chaplin TD, Clark RJH, Jacobs D, Jensen K, Smith GD. The Gutenberg Bibles: analysis of the illuminations and inks using Raman spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 2005;77(11):3611–22.

TM Texts 11968. https://www.trismegistos.org/text/11968. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Drexhage H-J. Preise, Mieten/Pachten, Kosten und Löhne im römischen Ägypten bis zum Regierungsantritt Diokletians, vol. 1. Scripta Mercaturae; 1991.

Diocletianus. Diokletians Preisedikt. Lauffer S, editor. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter & Co; 1971.

Zekrgoo SS. Methods of creating, testing and identifying traditional Black Persian inks. Restaurator. 2014;35(2):133–58.

Acknowledgements

This paper is the result of the collaboration of the DVCTVS Team, the PAThs project (La Sapienza, Rome) and the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und prüfung (Berlin). Our warm thanks go to all our colleagues from these institutions, and in particular to Paola Buzi and Ira Rabin for their constant support, and Olivier Bonnerot for his help with the XRF analysis of the papyri. We are deeply thankful to Claudia Colini for providing us with the mock-up samples of ink. Thanks to Alberto Nodar, curator of the Palau-Ribes Collection and Sofía Torallas Tovar, curator of the Roca-Puig Collection, for granting access to the manuscripts and for making the premises of their institutions available during the on-site analysis. Last but not least, warm thanks to David Howell for revising this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research has been funded by the European Research Council, Horizon 2020 Programme, with a 2015 ERC Advanced Grant designated to support the project “Tracking Papyrus and Parchment Paths: An Archaeological Atlas of Coptic Literature. Literary Texts in their Geographical Context: Production, Copying, Usage, Dissemination and Storage”, project no. 687567, P.I. Paola Buzi (http://paths.uniroma1.it/), and the Project “Reading Matter: Chartae, Inks and the Texts. Studies in Spanish Papyrus Collections” PGC2018-096572-B-C21, financed by MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE. The archaeometric analysis was supported by the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und-prüfung in Berlin, and by the Cluster of Excellence “Understanding written Artefacts” funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemainschaft, DFG) within the scope of the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures at the University of Hamburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TG performed the archaeometric analysis and interpretation of the data presented in this contribution and wrote the “Materials and methods” and “Results” sections. MJAM suggested which objects to analyse, and provided their historical and archaeological context. The interpretation of data within the historical context was carried out as a cooperation between the two authors and resulted in “Introduction”, “Discussion” and “Conclusions” sections. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

XRF spectrum of the supporting glass used to handle the papyri.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghigo, T., Albarrán Martínez, M.J. The practice of writing inside an Egyptian monastic settlement: preliminary material characterisation of the inks used on Coptic manuscripts from the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit. Herit Sci 9, 62 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00541-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00541-0