Abstract

Wireless power transmission was conceptualized nearly a century ago. Certain achievements made to date have made power harvesting a reality, capable of providing alternative sources of energy. This review provides a summ ary of radio frequency (RF) power harvesting technologies in order to serve as a guide for the design of RF energy harvesting units. Since energy harvesting circuits are designed to operate with relatively small voltages and currents, they rely on state-of-the-art electrical technology for obtaining high efficiency. Thus, comprehensive analysis and discussions of various designs and their tradeoffs are included. Finally, recent applications of RF power harvesting are outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Motivation for wireless energy harvesting

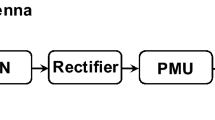

An early definition of a wireless power transmission system portrays a unit that emits electrical power from one place and captures it at another place in the Earth’s atmosphere without the use of wires or any other supporting medium [1]. The history of RF power scavenging in free space originated in the late 1950s with a microwave-powered helicopter system [2]. Later, the concept of power harvesting or energy scavenging was explained as a technique for reaping energy from the external environment using different methods including thermoelectric conversion, vibrational excitation, solar energy conversion, and pressure gradients. This technique promises tremendous scope for the replacement of small batteries in low power electrical devices and systems. Figure 1 introduces the structure of an RF energy harvesting system and factors that contribute to the performance of the whole system.

RF wireless power harvesting (WPH) holds vast potential for replacing batteries or increasing their lifespans. Currently, batteries power a majority of low-power remote sensor devices and embedded equipment. In fact, batteries have finite lifespans and require periodic replacements. By applying power harvesting technologies, devices and equipment can become self-sustaining with respect to the energy required for operation, thereby obtaining an unlimited operating lifespan. Thus, the demand for power maintenance will become negligible.

The sources for WPH are available in many forms, such as solar power [3–5], wind energy [6–8], thermal energy [9–11], electromagnetic energy [12–14], kinetic energy [15–17], etc. Among them, electromagnetic energy is abundant in space and can be retrieved without limit. Electromagnetic waves come from a variety of sources such as satellite stations, wireless internet, radio stations, and digital multimedia broadcasting. A radio frequency power harvesting system can capture and convert electromagnetic energy into a usable direct current (DC) voltage. The key units of an RF power harvesting system are the antenna and rectifier circuit that allows the RF power or alternating current (AC) to be converted into DC energy.

The processing of battery wastes is a critical problem. A majority of batteries end up in landfills, leading to the pollution of the land and water underneath. The most effective solution for reducing battery wastes is to avoid using them. Applying WPH technology will help to reduce the dependency on batteries, which will ultimately have a positive impact on the environment. Moreover, the process of harnessing electromagnetic energy will not generate wastes as it is a clean energy source.

A summary of the present sources of energy available for power harvesting is shown in Table 1. The data in Table 1 was collected from references [18, 19]. In comparison with thermal or kinetic energy, electromagnetic energy is not limited by space or time. The RF wave is available both indoors and outdoors, in rural and urban areas, throughout the day. Despite its low power density in the environment, an intentional source can be added for more efficient power transmission and a boosting circuit can be built to suit the requirements of the load application. This feature promotes research to realize RF WPH technology through applications such as wireless sensor networks (WSNs) and Internet of Things (IoT).

Fundamentals of RF transmission

Understanding electromagnetic waves is important to design an RF WPH system. The behavior of electromagnetic waves varies according to the distance, frequency, and conducting environment. Depending on the requirements of the application, the designer needs to select suitable parameters for electromagnetic waves to obtain best results.

The loss of power in space can be characterized by free space path loss (FSPL), which is the loss of signal power during propagation in free space. Calculating FSPL requires information about the antenna gain, frequency of transmitting wave, and distance between the transmitter and receiver.

The behavior of electromagnetic waves depends upon the distance from the transmitting antenna. These characteristics are categorized into two segments: far-field and near-field [20]. While the electromagnetic wave pattern at the far-field is relatively uniform, in the near-field, the electric and magnetic components are very strong and independent such that one component can dominate the other. The near-field region is considered as the space that lies within the Fraunhofer’s distance and the far-field region lies outside the Fraunhofer’s distance. The distribution of the near and far field regions is illustrated in Fig. 2. The Fraunhofer’s distance is defined as

where d f is the Fraunhofer’s distance, D is the maximum dimension of the radiator (or diameter of the antenna), and λ is the wavelength of the electromagnetic wave. Although the Fraunhofer creates a boundary region, the actual transition between regions is not distinct. Inside the near-field, the space from the antenna to a distance of \(\sqrt[3]{{\frac{D}{2\lambda }}}\) is a non-radiative/reactive near-field region, where E and H fields are not in phase, creating energy distortion. As we propagate forward in this region towards the far-field, we encounter a radiative near-field or Fresnel region, where the reactive behavior of electromagnetic waves is not dominant but the phases of E and H fields still vary with distance.

For a transmitter–receiver antenna in the far-field free space, the power propagation at the receiver antenna can be expressed as

where P R is power at the receiver antenna; G R is receiver antenna gain relative to the isotropic source (dBi); \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the electromagnetic signal, which is equal to the speed of light in vacuum divided by the signal frequency, \(\lambda = \frac{c}{f}\); and k = 2π/λ is the wave number. From the above formula, the FSPL, P L for far-field can be inferred as

or

In case f is measured in MHz, distance R is measured in km, and gain G T and G R are measured in dBi, the above function becomes

By using the path loss equation, it is possible to indicate the signal power at the far field region. However, this equation does not present all the factors that affect the propagation process such as reflection, diffraction, absorption, etc.

In contrast to the uniform far-field wave, the electric and magnetic fields behave unusually in the near-field. The relationship between electric and magnetic waves in the near-field varies unpredictably with time and space and is too complicated to predict. All these factors make estimating the power density at this range problematic.

The FSPL estimation process is critical to design the energy-harvesting unit. Being informed about the amount of power that the system is required to handle helps the designer in choosing the right technology and method.

Since the electromagnetic field (EMF) is widely used for a variety of purposes, there must be a standard to ensure the safe operation of EMF devices. For this purpose, the International Electrotechnical Commission [21] established international standards and frequency limits for EMFs. For safety measures, there must be a separate emission and immunity standard for each class of application including broadcast, communication, military, medical, and household appliances.

On the other hand, radiation exposure must be considered carefully, especially in biomedical applications. EMFs at different spectrums affect the human body differently. Between 1 MHz to 10 GHz frequency, EMF possibly penetrates through tissues and produce heat because of energy absorption. EMFs over 10 GHz are strongly blocked by the skin, and then the heat created causes damage such as eye cataracts or skin burns if the field density is above 1000 W/m2. Hoping to prevent negative health effects when utilizing EMF applications, the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) developed general guidelines for EMF exposure limits recognized under the World Health Organization (WHO). To date, there have been no consistent reports corroborating that lasting exposure to EMF shortens one’s life span or induces adverse health conditions. However, for safety issues, RF emission power and frequency must be considered carefully to avoid unwanted damages.

Wireless power harvesting evaluation metrics

There are various parameters that need to be evaluated, which decide the performance of a WPH design. Evaluation merits change depending on different applications. Nevertheless, critical values such as efficiency, sensitivity, operation distance, output power are defined as standards to make comparisons. However, tradeoffs exist between these values such as operation distance and overall efficiency. Moreover, besides this merit, other manufacturing auxiliary factors like low cost, maturity of fabrication process, and bulk manufacturing availability are also paramount.

Operation range

Operation distance is mostly related to operation frequency. In fact, transmission at high frequencies is attenuated by atmospheric conditions more than at low frequencies while low frequency penetrates deeper through matter. Therefore, if the application of WPH is for implantable devices, then the transmitting frequency should not exceed the megahertz range.

RF-DC power conversion efficiency (PCE)

This is the ratio between the amount of power applied to the load and that retrieved by the antenna. Generally, the RF-DC PCE covers the efficiency of the rectifier, voltage multiplier, and storage elements. PCE can be simply calculated as the ratio of power delivered to the load to the retrieved power. RF transmission loss in space is not considered in this term.

where Pload is power delivered to the load and Pretrieved is harvested power at the antenna. Factors that determine the value of PCE include parasitic effects, leakage in the circuits, design topologies, and nonlinear thresholds of electrical components.

Resonator Q factor

The Q factor is generally defined as a dimensionless value that describes how strong the resonance is and the bandwidth of resonance [22]. In electric circuits, the Q factor represents how much the peak voltage increases when the system resonates at resonant frequency. From this concept, the equation of Q factor can be express as the formula below [23]:

From the equation above, it is inferred that a high Q factor comes with a narrow resonant bandwidth, but high voltage gain is obtained at resonance. Further, this equation also indicates that the Q factor is inversely proportional to the energy dissipated per cycle. The specific Q factor for capacitor C and inductor L at frequency ω is given by

where RC is the series resistance of capacitor and RL is the series resistance of inductor. From the equations of QC and QL, we note that resistive component is the cause of power dissipation. Additionally, in an electrical circuit, energy loss can be reduced by adding reactive components such as capacitors or inductors and minimizing resistive components. Since obtaining a high Q factor is a usual consideration in designing WPH systems, this feature is typically included in the impedance matching network design.

Sensitivity

Sensitivity of a WPH system is defined as the minimum limit of incident power that is required to trigger the operation of the system. Sensitivity is quantified as follows:

where P is the minimum power the system requires to perform a task.

The threshold voltage of CMOS technology affects sensitivity. A lower threshold CMOS is more sensitive but comes with more leakage current, which reduces the overall efficiency.

Output power

Usually, the outcome of a WPH system is DC power, which is characterized by load voltage VDD and current IDD. Measuring open-load voltage demonstrates the performance of WPH in general since VDD and IDD depend on load impedance. If the load is a sensor, VDD is more important than IDD while in applications like electrolysis or LED, current is the dominant parameter.

Recent advances in wireless power harvesting

Antenna/rectenna design

Gain, resonance frequency, bandwidth are parameters that characterize the performance of an antenna. Assuming an unobstructed space and isotropic transmitting source, the spreading of the waves in all directions is uniform. Thus, the power per unit area at a distance from the source is inversely proportional to the square of the distance:

where R is the distance from the source, S is power per unit area at the distance R, and \(P_{T}\) is the transmitted power.

However, it is important to note that antennas do not always transmit power spherically (isotropic antenna), they also transmit energy in some specific directions according to their designs. The ratio between the maximum power density of an antenna at a given distance to the power density of an optimal omnidirectional or isotropic antenna at the same distance, radiating the same power, is known as antenna gain (G). This parameter represents the directivity of an antenna. Since power density (S) is non-directional, the definition of S was developed as a function of direction i.e. S (θ, \(\varphi\)). Consequently, the gain of the antenna is a directional function as well. It is defined as the ratio of the antenna’s power density in a given direction to the power density of an isotropic antenna as formula below

Thus, the power density at a distance R from an antenna in general is given by

where PT is the transmitted power by the antenna and GT is the transmitting antenna gain. It is known that an ideal isotropic antenna has GT = 0 dBi. The aforementioned formula is also applicable to receiving antennas. Specifically, for power harvesting applications, a receiving antenna, which constitutes a rectifier, is called a rectenna.

Preference for a high gain antenna depends on the application requirements. In case of RF transmission, if the positions of source and receiving antennas are known, then a high gain rectenna is advantageous. On the other hand, if the positions of the source and receiving antenna are relatively uncertain, a low gain antenna is preferable in order to collect signals from various directions simultaneously.

Every antenna has its own optimal operation frequency known as resonance frequency (Fig. 3). The resonance frequency is determined by the capacitance and inductance characteristics of the antenna. As frequency increases, inductive behavior becomes dominant and capacitance decreases. The frequency at which the inductance and capacitance nullify each other, minimizing the impedance of the antenna, is called the resonance frequency.

The capacitance and inductance are functions of the frequency and physical size of the antenna. The larger the dimensions of the antenna, the lower the resonance frequency. Therefore, transmitting and receiving low frequency waves requires a large aperture, which is not suitable for small device applications. The antenna designed in [24] has a sensitivity as low as −35 dBm (0.32 µW), but the tradeoff is a large size aperture measuring up to 64.68 cm3 (7 × 7 × 1.32 cm).

The bandwidth of an antenna is the range of frequencies in which the antenna can operate efficiently. A wide bandwidth antenna can collect signals from a wider range of frequencies than a narrow bandwidth antenna. Hence, a wide bandwidth antenna is advantageous in retrieving incident energy but presents a high risk of interference by noise through unwanted frequencies (Table 2).

Communication antennas have been studied for decades. However, power-harvesting antennas are currently in the developmental stage. At first, antenna classification was based on design characteristics and applications. It originally included wire antennas, aperture antennas, printed planar antennas, and reflector antennas. An illustration of some examples of antennas is shown in Fig. 4. To date, the growth in technology has paved the way for a variety of antenna design and fabrication methods for making it more compact and mature.

Types of antennas a 2.45 GHz patch antenna with rectifier [38]. ©2010 IEEE. All rights reserved; b Planar dual-polarized antenna [24]. ©2015 IEEE. All rights reserved; c Microstrip antenna [37]. ©2012 IEEE. All rights reserved; d Array of stacked differential patch antenna [33]. ©2015 IEEE. All rights reserved

The plate antennas are popular and have many applications [27, 34, 38]; on-chip antennas are preferred for small and compact applications. Recently, many publications addressed wide-band and multi-band antennas. It has been proven that narrow-band antennas offer high energy conversion efficiencies but can only retrieve a limited amount of energy. On the other hand, wide-band or multi-band frequency antennas can retrieve more RF energy in space. However, the tradeoffs are low overall efficiency and large aperture. In [32], antennas with a resonance frequency of 4.9 and 5.9 GHz were designed with PCEs of 65.2 and 64.8%, respectively. Further work by Lu et al. [26] on polarization antennas supports the assertion that expanding the bandwidth of an antenna leads to increasing the amount of power harvested. In this work, the demonstration of broadband polarization antennas with three separate modes allows the antenna to operate in a wider range of frequencies. One common mechanism in the aforementioned works is the control of the antenna configuration by switching the diodes on and off, thus altering its resonant frequencies. However, since it uses separate modes for different frequencies, this antenna is not able to simultaneously resonate at two frequencies. On the other hand, the antenna presented in [39] is capable of operating at 2.45 and 5.8 GHz, simultaneously, providing 2.6 V output with a PCE of 65% and power density of 10 mW/cm2.

The main purpose of aligning antennas in arrays is to enhance the antenna gain and obtain high voltage/current. Array antennas are preferred over large aperture antennas because they do not require large breakdown voltage diodes to operate. Antenna arrays can be connected before or after rectification. The first configuration enhances the retrieved power at the main beam while the second configuration expands the ability to retrieve power from various angles away from the main beam [40]. In case the RF waves are combined before rectification, the rectifier requires a large breakdown diode. If RF waves are combined after rectification, combining DC current becomes problematic. Antenna arrays can be connected in series or parallel to obtain high voltage or large current. Nonetheless, expanding the arrays yields better output but this might cause a deduction in conversion efficiency [33].

For demonstrating antenna arrays, Sun et al. [35] invented a T-junction to connect four quasi-Yagi antennas together. The advancement in this work was that the T-junction was flexible in changing from 1 × 4 array to 2 × 2 array topologies. Consequently, the system was able to operate at an ambient power level as low as 455 µW/cm2 while obtaining 40% PCE.

Impedance matching network

In low-power consumption electrical systems, power leakage during transmission may lead to energy insufficiency. In these circumstances, adding an impedance matching network (IMN) ensures that the maximum power transfers between the RF source and load. For WPH applications, the receiving antenna is considered as the source while the rectifier/voltage multiplier is considered as the load. It is acknowledged that in DC, power transfer is optimum when the resistances of the source and load are indistinguishable. In an RF circuit, the impedance is referred to instead of resistance. An impedance mismatch between the source and load creates reflected power flow in the circuit that lowers the efficiency of the system. As its name indicates, the IMN ensures that the impedance of the source and load are identical by adding reactive components in between.

There are three basics matching configurations i.e. L, T and π matching networks (Fig. 5). The L matching is commonly used since it typically has two components, which simplifies the designing and controlling process. Additionally, the L matching networks do not alter the quality factor (Q) of the circuit.

The T and π matching configurations are more complex than the L network. Furthermore, organizing the T and π configurations into multiple stages will retain the final matching results but will change the Q factor. This strategy is useful in improving voltage boost.

There are tradeoffs between the attributes of an IMN, which include frequency, bandwidth, adjustability, and complexity. For instant, in [41], the suboptimal impedance matching and multiport ladder matching methods were introduced to enhance the matching performance and harvested power of antennas, respectively. However, the tradeoff was that implementation of these configurations required more components than traditional matching networks, thus, escalating the circuit’s complexity.

Etor et al. [42] designed an IMN for THz frequencies applications using transmission lines and self-designed metal–insulator-metal diodes instead of lumped components. Moreover, fixed IMN and tunable IMN [43–45] were introduced as a technique for better matching with wide-band and multi-band antennas.

Rectifier/voltage multiplier

RF energy extracted from free space usually possesses low power density since the electric field power density decreases at the rate of 1/d2, where d is the distance from the RF source [46]. Therefore, a power amplifier circuit is required that yields enough DC energy from the electromagnetic waves to drive the loads. This gives rise to two possibilities, if the power consumption of the load is lower than the average power harvesting, the electronic devices at the load may work continuously; otherwise, if the load consumes more energy than the power harvesting circuit can generate, the devices cannot work continuously [47].

Rectifying is the most popular application of diodes, which refers to the conversion of AC current to DC current. In terms of power harvesting application, the RF signal retrieved in the antenna has a sinusoidal waveform. The signal after transformation through IMN would be rectified and boosted to meet the power requirements of the application.

The most fundamental topology of the rectifier is the half-wave rectifier that comprises of a single diode D1 (Fig. 6a). When AC voltage transfers through D1, only the positive cycle remains and the negative cycle is cutoff; thus, it diminishes half of the AC power. Moreover, the output Vout is discontinuous since the negative cycle is cutoff. Despite its simplicity, a half-wave rectifier is usually inadequate for common applications. Hence, a full-wave rectifier is more preferable. The circuit design of the full-wave rectifier is shown in Fig. 6b. During the first negative cycle of AC input, diode D1 is conductive and capacitor C1 is charged to the corresponding energy level of Vpeak of the input. Then, at the next positive cycle, diode D1 is blocked, diode D2 is conductive so that capacitor C2 is also charged. In consequence, the output Vout would see two capacitors in series (each one is storing a voltage of Vpeak). Thus, Vout is twice Vpeak. Therefore, this topology is more stable and efficient than the half-wave rectifier. There is also a bridge rectifier that rectifies both positive and negative cycles of the AC input but retains Vout = Vpeak by alternatively blocking pairs of diodes D1, D4 and D2, D3 (Fig. 6c).

Voltage multiplier is a special type of rectifier circuit that converts and boosts AC input to DC output. In some case where the rectified power is inadequate for the application, there is a need for boosting the output DC by stacking single rectifiers into series, forming the voltage multiplier [48]. Several configurations of the voltage multiplier are shown in Fig. 7. The most fundamental configuration is the Cockcroft–Walton voltage multiplier (Fig. 7a). This circuit’s operational principle is similar to the full-wave rectifier (Fig. 6b) but has more stages for higher voltage gain. The Dickson multiplier in Fig. 7b is a modification of Cockcroft–Walton’s configuration with stage capacitors being shunted to reduce parasitic effects. Thus, the Dickson multiplier is preferable for small voltage applications. However, it is challenging to obtain high PCE due to the high threshold voltage among diodes creating leakage current, thus reducing the overall efficiency. Additionally, for high resistance loads, output voltage drops drastically leading to low current supply to the load. A summary of recent works related to voltage multiplier is shown in Table 3.

The MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor field effect transistor) technology is overcoming the limitations of diodes and becoming an alternate solution for rectifying and boosting. Owing to MOSFET technology, Dickson multiplier can be integrated together in integrate circuits (IC) by replacing diodes with NMOS as shown in Fig. 7c. Relatively low threshold voltages and high PCEs are features of this design. Moreover, differential drive voltage multiplier (Fig. 7d) is widely used because of its low leakage current and potential for further modification for specific applications. A detail explanation and analysis is presented in [49, 50].

There is a strong relationship between the number of stages of a voltage multiplier and its sensitivity and efficiency. As the number of stages increase, there is more loss across each added stage. However, the tradeoff is higher voltage multiplication and small threshold voltage at the first stage. On the other hand, a voltage multiplier with a few stages has less voltage drop between its stages but requires higher threshold voltage for all stages to work simultaneously. For this reason, a voltage multiplier becomes more sensitive when a large number of stages are present and becomes more efficient at fewer stages. This tradeoff feature was analyzed in several researches [53, 58]. Therefore, the optimal number of stages should be considered depending upon the application targets.

Pros and cons of Schottky diode and CMOS technology

Rectifying elements such as diodes or transistors are indispensable components of the rectifier/voltage multiplier block, which determine operation frequency and power-conversion efficiency. Traditionally, a Schottky diode was used because of its low threshold voltage. Moreover, there are also Esaki (tunnel) diodes, metal–insulator–metal (MIM) diodes, and spin diodes with recent technology enhancements that make it more mature. Particularly, the Esaki diode can operate at very high frequency with fast response because of its low parasitic elements. Moreover, the MIM diodes technology makes integration with CMOS process possible, which is a limitation of Schottky diodes. Spin diodes offer lower threshold voltages than Schottky diodes.

There are several parameters that need to be considered when choosing a diode for designing a voltage multiplier. These include RF to DC power conversion efficiency, parasitic efficiency, and matching efficiency. When it comes to microwatt applications, Schottky diodes face some limitation in RF-DC conversion efficiency because of their high zero-bias junction resistance [59]. However, owing to recent developments in technology, if the retrieved power is less than −30 dBm (1 µW), then the low-barrier SMS7630 and VDI W-Band ZBD diodes are recommended due to their low parasitic power losses and low power dissipation in the matching network [60].

Recently, many publications have moved toward CMOS processes, since they not only assist in custom designing in electronics but are also more sensitive to low operation voltages than traditional Schottky diodes. Many researches focus on modifying present rectifier and voltage multiplier topologies to achieve higher gain, sensitivity, efficiency [52, 55–57, 61]. For instance, the voltage multiplier achieved maximum 11% PCE at −24 dBm (4 µW) in [62] and 41% PCE at −20.6 dBm (8.7 µW) input power in [57]. While the majority of publications utilized 0.18 µm CMOS technology in their work, [52] applied commercial 40 nm CMOS process to build a low-voltage operation voltage multiplier that reached 44% PCE at 390 mV input. Hwang et al. [54] applied reducing reverse loss to minimize the reverse leakage loss in the rectifier, thus increasing the overall efficiency.

Similar to Schottky diodes, the number of stages directly dictates the performance efficiency in the task of designing a custom CMOS voltage multiplier. A basic assumption when using transistors is that the retrieved RF signal from the antenna must be high enough to trigger the transistors on and off. Different voltage multiplier topologies possess different features and characteristics. However, as long as transistors are used in the design, there is considerable amount of voltage drop among transistors. It has been observed that the major cause of rectified voltage drop is the threshold loss. If the number of stages increases, the threshold voltage at the transistors also adds up, requiring the higher amplitude RF signal to trigger the transistors [62]. Therefore, the number of stages in the majority of publications usually does not exceed 10.

Designing and optimizing the WPH system

The efficiencies of individual modules and the integration of all modules together constitute the total efficiency of a WPH system. As a consequence, the only way to optimize the total efficiency is to maximize efficiencies of each module and consolidate them in harmony. Commonly, several tests and adjustments need to be done to obtain an optimized WPH system. The work flow of designing a WPH system is described in Fig. 8.

Firstly, choosing the appropriate operation frequency to the application’s requirement critically dictates the efficiency of the WPH system. Secondly, the operation range also need to be specified. Long range (far-field) power harvesting or transmission requires high frequency such as 2.45, 5.24 GHz, whereas short range (near-field) applications requires electromagnetic waves at frequencies in the megahertz range. Additionally, for power harvesting in dense environment different from air, very low frequency (~kHz) is preferable. Besides the operation frequency and distance, the required output power and voltage determines the suitable topology of the voltage multiplier.

Based on the operation and application, the antenna’s design has to match the gain, frequency and size. Choosing the right rectifying element is also critical. For rectifier and voltage multiplier modules in general, the dependence of RF-DC PCE on frequency and output load was discussed in [50]. In addition, it is obligated to have a correct-tuned IMN for maximum power transfer inside the WPH circuit.

Detailed features of individual modules of the WPH system are explained and discussed in the previous sections. The problem of optimizing the WPH system becomes the game of defining the goals and integrating individual modules in harmony to archive the goal.

Applications

RF power harvesting in medical and healthcare

In order to deploy WPH in the real world, power consumption rate of the device should be less than the harvested power. Since retrieved power is unstable and difficult to predict, an energy storage module is highly recommended to enhance its consistency. If the WPH is integrated to the device as a single system on chip, the total size of the system would be reduced significantly.

The first wireless battery-free bio-signal processing system on chip [63] was introduced by [64]. This system was able to monitor various bio-signals via electrocardiogram (ECG), electromyogram (EMG), and electroencephalogram (EEG). The total size of the chip was 8.25 mm2. This chip only consumed 19 µW to measure heart rate. The power module of this system comprised an RF WPH that was supported by a thermoelectric generator, which together supplied a voltage of 1.35 V. Table 4 presents the performance of several health monitoring system on chips (SoCs). The majority of chips have the advantages of small size, low voltage supply and low power consumption which is applicable to be integrated with WPH technology.

It is a fact that a considerable amount of TV broadcast signals never reach the TV. Fortunately, WPH technology can harness this wasted energy without causing any effect on the TV broadcasting quality. In this context, Nishimoto et al. [71] have explored this potential source of energy to remove batteries from temperature monitoring WSNs. Since the power density of TV broadcasts is relatively weak, an array antenna was designed to collect multi-frequency waves. Compared to the antenna array designed in [72], the antenna rectifying efficiency obtained was higher by 50% in the frequencies between 15 and 800 MHz. This design is reported to successfully measure and transmit data every 5 s.

In some research experiments where free movement is unavoidable, stimulation signal and response data has to be delivered and collected wirelessly. In these circumstances, RF WPH is a superior choice in comparison with inductive coupling transmission technology to power the wireless system. Cobo et al. designed an implantable micro-pump that is powered by inductive coupling coils. Even though this work has obtained high efficiency power transmission, the operation range is limited to a few centimeters from the source. On the other hand, in [73], the RF electromagnetic waves were deployed to power optogenetic microneedles to be wirelessly injected into mice. The design of WPH in this work was able to retrieve 4.08 mW power at a distance of 1 m from the 7.9 W source at a frequency of 910 MHz. Another rectenna was built for mounting on the mice’ heads for deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices [31]. In this system, the power-harvesting module retrieves 0.254 mW DC power at a maximum operation distance of 20 cm. With this available power, the DBS device generates 200 µA pulses at 130 Hz. The above results show that RF WPH technology offers a better operation range than traditional inductive coupling power transmission technology. It is now possible to harvest sufficient power to run low-power consumption devices in the range of meters. The noninvasive bio-telemetry system for monitoring and investigating various health indexes is a promising field for WPH technology. Cheng et al. [74] introduced a power harvesting design that included a loop antenna to be attached to the pig eye with 31% PCE and output power up to 2.10 mW. Additionally, in vivo experiments, using WPH technology to supply medical devices for implantation in rapid eyes was demonstrated without recorded side effects [63, 75].

Wireless power harvesting network (IoT/WSN)

Along with the development of the micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) technology, wireless sensor networks have gained widespread popularity in recent years. This field has achieved several milestones and is still developing further. WSNs applications widespread from smart house, healthcare to industry and military. In addition to the issues of sensing reliability, communication protocol, and network services, energy is a critical concern in WSNs [76]. Sensor nodes of WSNs are low power devices, and minimization of energy consumption and application of WPH to replenish power storage elements are two concurrent schemes to maximize the network lifespan. Recently, several researches were done to find optimized approaches to power WSNs including RF power harvesting [77–81].

Energy is the greatest challenge in deploying WSNs [82]. Applying RF energy to recharge the batteries is one approach to enhance the lifespan of WSNs [83, 84]. Lee et al. [85] is an example of an RF charger utilizing WPH technology. The system was able to work with a minimum input power of −10 dBm (0.1 mW) in the frequency range from 1.96 to 1.98 GHz to charge a 5 V super-capacitor. Maximum RF to DC power conversion efficiency is 81% at 6 dBm (3.98 mW). Gudan et al. [86] also designed a WPH system to charge a NiMH battery using either ambient Wi-Fi or Bluetooth signals. With the sensitivity down to −20 dBm, this system was capable of charging a battery to 5.8 µJ after 1 h.

Table 5 lists some low-power consumption sensor applications that can be integrated with a WPH module. The majority of these sensors were powered by battery with limited lifetime. Once WPH technology is implemented with these applications, it could be used in as a wireless sensor node. In particular, the work presented in [81] utilized RF power harvesting into WSNs for building’s structure monitoring. In this work, far-field RF powered wireless sensors were developed with novel data transmission approach to detect humidity, temperature and light inside a building. Results show at a distance of 1 m from 3 W source, the sensor node received 3.14 mW power through air, 1.53 mW of power through 2 inches of brick, 2.88 mW through wood and 0.7 mW through 2 inches of steel. This amount of power is sufficient for the sensors presented in [88–91]. This result indicates the applicability of RF WPH toward WSNs.

Furthermore, placement of power transmitters and sensor nodes in WSNs also play a critical role in the efficiency of the system [94–96]. To enhance directivity of RF transmissions, Shao et al. [97] proposed a beam-steered antenna array to direct its main beam toward energy harvesting units. By controlling the length of transmission line to each antenna unit in an array, the phase radiating difference between units created shift in the main beam. By this way, the harvesting unit remains fed with energy even it was misaligned with the source by 35°. Using the harvesting unit presented in [98] as a demonstration, within 1 min, this system was able to harvest 68.7 µJ at 0° and 13.6 µJ at 35° at a distance of 2 m from the beam-steered source antenna array.

Conclusion

This paper summarized the state-of-the-art of RF power harvesting technology in recent years. This technology will play a key role in replacing batteries in the near future. Some applications of RF power harvesting have been practically realized. A basic RF power-harvesting unit includes three main modules: the antenna, IMN, and voltage multiplier. The total efficiency of the system is dictated by the harmony in the integration of all the modules. The designs and principles of each module were also discussed in the paper.

The RF electromagnetic waves are harmless, abundant in space, and is able to penetrate through soft tissues. Those are properties that make RF electromagnetic waves an alternative source of energy to replace batteries in many applications. Particularly, RF power harvesting supports low-power medical and healthcare devices and facilitates the development of WSNs and IoT by providing mobility of use. Additionally, the progress in integrating RF power harvesting circuits into CMOS technology creates a completely wireless SoC.

Besides progressive accomplishment in recent years, there are still a variety of rooms to further optimize the RF power harvesting technology such as increasing operation range, reducing transmission loss, optimizing PCE, and minimizing system dimensions are the targets of RF power harvesting research. Furthermore, research focusing on harsh working environments for RF WPH such as implantation conditions or underwater zones is attracting much attention to extend the capabilities of this technology. A fine manufacturing and packing process with cost-effective production is necessary to make this technology mature.

In short, the RF WPH technology is gradually becoming a reality. Although this technology still faces many issues, overcoming these challenges can lead the power industry into a new era of clean and sustainable energy.

References

Brown WC (1996) The history of wireless power transmission. Solar Energy 56:3–21

Brown WC (1969) Experiments involving a microwave beam to power and position a helicopter. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst AES-5:692–702

Raghunathan V, Kansal A, Hsu J, Friedman J, Srivastava M (2005) Design considerations for solar energy harvesting wireless embedded systems. In: Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on Information processing in sensor networks, p 64

Brunelli D, Benini L, Moser C, Thiele L (2008) An efficient solar energy harvester for wireless sensor nodes. In: 2008 design, automation and test in europe, pp 104–109

Abdin Z, Alim MA, Saidur R, Islam MR, Rashmi W, Mekhilef S et al (2013) Solar energy harvesting with the application of nanotechnology. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 26:837–852

Ackermann T, Söder L (2000) Wind energy technology and current status: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 4:315–374

GM Joselin Herbert, S. Iniyan, E. Sreevalsan, and S. Rajapandian, “A review of wind energy technologies,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 11, pp. 1117-1145, 8//2007

Şahin AD (2004) Progress and recent trends in wind energy. Prog Energy Combust Sci 30:501–543

Xin L, Shuang-Hua Y (2010) Thermal energy harvesting for WSNs. In: 2010 IEEE international conference on systems man and cybernetics (SMC), pp 3045–3052

Dalola S, Ferrari V, Marioli D (2010) Pyroelectric effect in PZT thick films for thermal energy harvesting in low-power sensors. Procedia Eng 5:685–688

Cuadras A, Gasulla M, Ferrari V (2010) Thermal energy harvesting through pyroelectricity. Sens Actuators A Phys 158:132–139

Cao X, Chiang WJ, King YC, Lee YK (2007) Electromagnetic energy harvesting circuit with feedforward and feedback DC–DC PWM boost converter for vibration power generator system. IEEE Trans Power Electron 22:679–685

Beeby SP, Torah RN, Tudor MJ, Glynne-Jones P, Donnell TO, Saha CR et al (2007) A micro electromagnetic generator for vibration energy harvesting. J Micromech Microeng 17:1257

Yang B, Lee C, Xiang W, Xie J, He JH, Kotlanka RK, Low SP, Feng H (2009) Electromagnetic energy harvesting from vibrations of multiple frequencies. J Micromech Microeng 19:035001

Beeby SP, Tudor MJ, White NM (2006) Energy harvesting vibration sources for microsystems applications. Meas Sci Technol 17:R175

Challa VR, Prasad M, Shi Y, Fisher FT (2008) A vibration energy harvesting device with bidirectional resonance frequency tunability. Smart Mater Struct 17:015035

Khaligh A, Zeng P, Zheng C (2010) Kinetic energy harvesting using piezoelectric and electromagnetic technologies—state of the art. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 57:850–860

Vullers RJM, van Schaijk R, Doms I, Van Hoof C, Mertens R (2009) Micropower energy harvesting. Solid-State Electron 53:684–693

Akhtar F, Rehmani MH (2015) Energy replenishment using renewable and traditional energy resources for sustainable wireless sensor networks: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 45:769–784

Yaghjian A (1986) An overview of near-field antenna measurements. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 34:30–45

Chen G, Ghaed H, Haque RU, Wieckowski M, Kim Y, Kim G et al (2011) A cubic-millimeter energy-autonomous wireless intraocular pressure monitor. In: 2011 IEEE international solid-state circuits conference, 2011, pp 310–312

Harlow JH (2004) Electric power transformer engineering. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Lee TH (2004) The design of cmos radio-frequency integrated circuits. Commun Eng 2:47

Song C, Huang Y, Zhou J, Zhang J, Yuan S, Carter P (2015) A high-efficiency broadband rectenna for ambient wireless energy harvesting. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 63:3486–3495

Momenroodaki P, Fernandes RD, Popovi Z (2016) Air-substrate compact high gain rectennas for low RF power harvesting. In: 2016 10th European conference on antennas and propagation (EuCAP), pp 1–4

Lu P, Yang XS, Li JL, Wang BZ (2016) Polarization reconfigurable broadband rectenna with tunable matching network for microwave power transmission. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 64:1136–1141

Sun H (2016) An enhanced rectenna using differentially-fed rectifier for wireless power transmission. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 15:32–35

Sun H, Geyi W (2016) A new rectenna with all-polarization-receiving capability for wireless power transmission. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 15:814–817

Zhu P, Ma Z, Vandenbosch GAE, Gielen G (2015) 160 GHz harmonic-rejecting antenna with CMOS rectifier for millimeter-wave wireless power transmission. In: 2015 9th European conference on antennas and propagation (EuCAP), pp 1–5

Zhang J, Wu ZP, Liu CG, Zhang BH, Zhang B (2015) A double-sided rectenna design for RF energy harvesting. In: 2015 IEEE international wireless symposium (IWS), pp 1–4

Hosain MK, Kouzani AZ, Samad MF, Tye SJ (2015) A miniature energy harvesting rectenna for operating a head-mountable deep brain stimulation device. IEEE Access 3:223–234

Lu P, Yang XS, Li JL, Wang BZ (2015) A compact frequency reconfigurable rectenna for 5.2- and 5.8-GHz wireless power transmission. IEEE Trans Power Electron 30:6006–6010

Matsunaga T, Nishiyama E, Toyoda I (2015) 5.8-GHz stacked differential rectenna suitable for large-scale rectenna arrays with DC connection. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 63:5944–5949

Chou JH, Lin DB, Weng KL, Li HJ (2014) All polarization receiving rectenna with harmonic rejection property for wireless power transmission. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 62:5242–5249

Sun H, Guo Y, He M, Zhong Z (2013) A dual-band rectenna using broadband yagi antenna array for ambient RF power harvesting. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 12:918–921

Niotaki K, Kim S, Jeong S, Collado A, Georgiadis A, Tentzeris MM (2013) A compact dual-band rectenna using slot-loaded dual band folded dipole antenna. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 12:1634–1637

Hucheng S, Yong-Xin G, Miao H, Zheng Z (2012) Design of a high-efficiency 2.45-GHz rectenna for low-input-power energy harvesting. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 11:929–932

Olgun U, Chen CC, Volakis JL (2010) Wireless power harvesting with planar rectennas for 2.45 GHz RFIDs. In: 2010 URSI international symposium on electromagnetic theory (EMTS), pp 329–331

Ren YJ, Farooqui MF, Chang K (2007) A compact dual-frequency rectifying antenna with high-orders harmonic-rejection. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 55:2110–2113

Olgun U, Chen CC, Volakis JL (2011) Investigation of rectenna array configurations for enhanced RF power harvesting. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 10:262–265

Shen S, Murch RD (2016) Impedance matching for compact multiple antenna systems in random RF fields. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 64:820–825

Etor D, Dodd LE, Wood D, Balocco C (2015) Impedance matching at THz frequencies: optimizing power transfer in rectennas. In: 2015 40th international conference on infrared, millimeter, and terahertz waves (IRMMW-THz), pp 1–2

Hoarau C, Corrao N, Arnould JD, Ferrari P, Xavier P (2008) Complete design and measurement methodology for a tunable RF impedance-matching network. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech 56:2620–2627

Marrocco G (2008) The art of UHF RFID antenna design: impedance-matching and size-reduction techniques. IEEE Antennas Propag Mag 50:66–79

Mingo JD, Valdovinos A, Crespo A, Navarro D, Garcia P (2004) An RF electronically controlled impedance tuning network design and its application to an antenna input impedance automatic matching system. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech 52:489–497

Hatay M (1980) Empirical formula for propagation loss in land mobile radio services. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 29:317–325

Radiom S, Vandenbosch G, Gielen G (2008) Impact of antenna type and scaling on scavenged voltage in passive RFID tags. In: International workshop on antenna technology: small antennas and novel metamaterials, 2008. iWAT 2008, pp 442–445

Gosset G, Flandre D (2011) Fully-automated and portable design methodology for optimal sizing of energy-efficient CMOS voltage rectifiers. IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Circuits Syst 1:141–149

Facen A, Boni A (2007) CMOS power retriever for UHF RFID tags. Electron Lett 43:1424

Kotani K, Sasaki A, Ito T (2009) High-efficiency differential-drive CMOS rectifier for UHF RFIDs. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 44:3011–3018

Chouhan SS, Nurmi M, Halonen K (2016) Efficiency enhanced voltage multiplier circuit for RF energy harvesting. Microelectron J 48:95–102

Wang W, Xiangjie C, Wong H (2015) Analysis and design of CMOS full-wave rectifying charge pump for RF energy harvesting applications. In: 2015 IEEE Region 10 conference TENCON 2015, pp 1–4

Rodriguez AN, Cruz FRG, Ramos RZ (2015) Design of 900 Mhz AC to DC converter using native Cmos device of TSMC 0.18 micron technology for RF energy harvest application. Univers J Electr Electron Eng 3:7

Hwang YS, Lei CC, Yang YW, Chen JJ, Yu CC (2014) A 13.56-MHz low-voltage and low-control-loss RF-DC rectifier utilizing a reducing reverse loss technique. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29:6544–6554

Haddad PA, Gosset G, Raskin JP, Flandre D (2014) Efficient ultra low power rectification at 13.56 MHz for a 10 µA load current. In: 2014 SOI-3D-subthreshold microelectronics technology unified conference (S3S), pp 1–2

Hameed Z, Moez K (2014) Hybird forward and backward threshold-compensated RF-DC power converter for RF energy harvesting. IEEE J Eng Sel Top Circuits Syst 4:9

Karolak D, Taris T, Deval Y, Béguéret JB et al (2012) Design comparison of low-power rectifiers dedicated to RF energy harvesting. In: 2012 19th IEEE international conference on electronics, circuits and systems (ICECS), pp 524–527

Kadupitiya JCS, Abeythunga TN, Ranathunga PDMT, De Silva DS (2015) Optimizing RF energy harvester design for low power applications by integrating multi stage voltage doubler on patch antenna. In: 2015 8th international conference on Ubi-Media computing (UMEDIA), pp 335–338

Hemour S, Zhao Y, Lorenz CHP, Houssameddine D, Gui Y, Hu CM et al (2014) Towards low-power high-efficiency RF and microwave energy harvesting. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech 62:965–976

Lorenz CHP, Hemour S, Wu K (2016) Physical mechanism and theoretical foundation of ambient RF power harvesting using zero-bias diodes. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech 64:2146–2158

Sun H, Xu G (2015) A differentially-driven rectifier for enhanced RF power harvesting. In: 2015 IEEE MTT-S international microwave workshop series on advanced materials and processes for RF and THz applications (IMWS-AMP), pp 1–3

Papotto G, Carrara F, Palmisano G (2011) A 90-nm CMOS threshold-compensated RF energy harvester. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 46:1985–1997

Lingley AR, Ali M, Liao Y, Mirjalili R, Klonner M, Sopanen M et al (2011) A single-pixel wireless contact lens display. J Micromech Microeng 21:125014

Zhang Y, Zhang F, Shakhsheer Y, Silver JD, Klinefelter A, Nagaraju M et al (2013) A batteryless 19 W MICS/ISM-band energy harvesting body sensor node SoC for ExG applications. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 48:199–213

Helleputte NV, Konijnenburg M, Pettine J, Jee DW, Kim H, Morgado A et al (2015) A 345 uW multi-sensor biomedical SoC with bio-impedance, 3-channel ECG, motion artifact reduction, and integrated DSP. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 50:230–244

Kim H, Kim S, Helleputte NV, Artes A, Konijnenburg M, Huisken J et al (2014) A configurable and low-power mixed signal SoC for portable ECG monitoring applications. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 8:257–267

Yan L, Bae J, Lee S, Roh T, Song K, Yoo HJ (2011) A 3.9 mW 25-electrode reconfigured sensor for wearable cardiac monitoring system. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 46:353–364

Verma N, Shoeb A, Bohorquez J, Dawson J, Guttag J, Chandrakasan AP (2010) A micro-power EEG acquisition SoC with integrated feature extraction processor for a chronic seizure detection system. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 45(4):804–816

Chen G, Fojtik M, Kim D, Fick D, Park J, Seok M et al. (2010) Millimeter-scale nearly perpetual sensor system with stacked battery and solar cells. In: 2010 IEEE international solid-state circuits conference—(ISSCC), pp 288–289

Rai S, Holleman J, Pandey JN, Zhang F, Otis B (2009) A 500 µW neural tag with 2 µVrms AFE and frequency-multiplying MICS/ISM FSK transmitter. In: 2009 IEEE international solid-state circuits conference—digest of technical papers, pp 212–213

Nishimoto H, Kawahara Y, Asami T (2010) Prototype implementation of ambient RF energy harvesting wireless sensor networks. In: Sensors, 2010 IEEE, pp 1282–1287

Shinohara N, Kawasaki S (2009) Recent wireless power transmission technologies in Japan for space solar power station/satellite. In: 2009 IEEE radio and wireless symposium, pp 13–15

Kim T-I, McCall JG, Jung YH, Huang X, Siuda ER, Li Y et al (2013) Injectable, cellular-scale optoelectronics with applications for wireless optogenetics. Science 340:211–216

Cheng HW, Yu TC, Huang HY, Ting SH, Huang TH, Chiou JC et al (2014) Design of miniaturized antenna and power harvester circuit on the enucleated porcine eyes. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett 13:1156–1159

Chow EY, Yang CL, Ouyang Y, Chlebowski AL, Irazoqui PP, Chappell WJ (2011) Wireless powering and the study of RF propagation through ocular tissue for development of implantable sensors. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 59:2379–2387

Yick J, Mukherjee B, Ghosal D (2008) Wireless sensor network survey. Comput Netw 52:2292–2330

Correia R, Carvalho NB, Kawasaki S (2016) Continuously power delivering for passive backscatter wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech 64:3723–3731

Praveen MP, Mehta NB (2016) Trade-offs in analog sensing and communication in RF energy harvesting wireless sensor networks. In: 2016 IEEE international conference on communications (ICC), pp 1–6

Collado A, Georgiadis A (2014) Optimal waveforms for efficient wireless power transmission. IEEE Microwave Wirel Compon Lett 24:354–356

Zhao Y, Chen B, Zhang R (2013) Optimal power allocation for an energy harvesting estimation system. In: 2013 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing, pp 4549–4553

Ruisi G, Hong P, Zhibin L, Na G, Jinhui W, Xiaowei C (2016) RF-powered battery-less wireless sensor network in structural monitoring. In: 2016 IEEE international conference on electro information technology (EIT), pp 0547–0552

Seah WKG, Eu ZA, Tan HP (2009) Wireless sensor networks powered by ambient energy harvesting (WSN-HEAP)—survey and challenges. In: 2009 1st international conference on wireless communication, vehicular technology, information theory and aerospace and electronic systems technology, pp 1–5

Jabbar H, Song YS, Jeong TT (2010) RF energy harvesting system and circuits for charging of mobile devices. IEEE Trans Consum Electron 56:247–253

Che W, Chen W, Meng D, Wang X, Tan X, Yan N et al (2010) Power management unit for battery assisted passive RFID tag. Electron Lett 46:589–590

Lee JH, Jung WJ, Jung JW, Jang JE, Park JS (2015) A matched RF charger for wireless RF power harvesting system. Microw Opt Technol Lett 57:1622–1625

Gudan K, Chemishkian S, Hull JJ, Thomas SJ, Ensworth J, Reynolds MS (2014) A 2.4 GHz ambient RF energy harvesting system with −20 dBm minimum input power and NiMH battery storage. In: RFID technology and applications conference (RFID-TA), 2014 IEEE, pp 7–12

Nagaraju MB, Lingley AR, Sridharan S, Gu J, Ruby R, Otis BP (2015) A 0.8 mm3 ± 0.68 psi single-chip wireless pressure sensor for TPMS applications. In: 2015 IEEE international solid-state circuits conference—(ISSCC) digest of technical papers, pp 1–3

Gong S, Schwalb W, Wang Y, Chen Y, Tang Y, Si J et al (2014) A wearable and highly sensitive pressure sensor with ultrathin gold nanowires. Nat Commun 5:3132

Souri K, Chae Y, Makinwa KAA (2013) A CMOS temperature sensor with a voltage-calibrated inaccuracy of ±0.15 °C (3σ) from −55 °C to 125 °C. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 48:292–301

Aita AL, Pertijs MAP, Makinwa KAA, Huijsing JH, Meijer GCM (2013) Low-power CMOS smart temperature sensor with a batch-calibrated inaccuracy of ±0.25 °C (±3σ) from −70 °C to 130 °C. IEEE Sens J 13:1840–1848

Jeong S, Foo Z, Lee Y, Sim JY, Blaauw D, Sylvester D (2014) A fully-integrated 71 nW CMOS temperature sensor for low power wireless sensor nodes. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 49:1682–1693

Moon SE, Lee HK, Choi NJ, Kang HT, Lee J, Ahn SD et al (2015) Low power consumption micro C2H5OH gas sensor based on micro-heater and ink jetting technique. Sens Actuators B Chem 217:146–150

Zhou Q, Sussman A, Chang J, Dong J, Zettl A, Mickelson W (2015) Fast response integrated MEMS microheaters for ultra low power gas detection. Sens Actuators A Phys 223:67–75

Erol-Kantarci M, Mouftah HT (2012) Mission-aware placement of RF-based power transmitters in wireless sensor networks. In: 2012 IEEE symposium on computers and communications (ISCC), pp 000012–000017

He S, Chen J, Jiang F, Yau DKY, Xing G, Sun Y (2013) Energy provisioning in wireless rechargeable sensor networks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput 12:1931–1942

Li Y, Fu L, Chen M, Chi K, Zhu YH (2015) RF-based charger placement for duty cycle guarantee in battery-free sensor networks. IEEE Commun Lett 19:1802–1805

Shao S, Gudan K, Hull JJ (2016) A mechanically beam-steered phased array antenna for power-harvesting applications [Antenna Applications Corner]. IEEE Antennas Propag Mag 58:58–64

Gudan K, Shao S, Hull JJ, Ensworth J, Reynolds MS (2015) Ultra-low power 2.4 GHz RF energy harvesting and storage system with −25 dBm sensitivity. In: 2015 IEEE international conference on RFID (RFID), pp 40–46

Authors’ contributions

LGT carried out literature search and wrote the manuscript. HKC and WTP reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant No. 10060065 from the Industrial Source Technology Development Programs of the MOTIE (Ministry Of Trade, Industry and Energy), Korea. This work was also supported by the Radiation Technology R&D program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2013M2A2A9043274).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, LG., Cha, HK. & Park, WT. RF power harvesting: a review on designing methodologies and applications. Micro and Nano Syst Lett 5, 14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40486-017-0051-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40486-017-0051-0