Abstract

Background

There is little effective psychopharmacological treatment for individuals with eating disorders who struggle with pervasive, severe affective and behavioral dysregulation.

Methods

This pilot open series evaluated lamotrigine, a mood stabilizer, in the treatment of patients with eating disorders who did not respond adequately to antidepressant medications. Nine women with anorexia nervosa- or bulimia nervosa-spectrum eating disorders in partial hospital or intensive outpatient dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)-based eating disorder treatment took lamotrigine for 147 ± 79 days (mean final dose = 161.1 ± 48.6 mg/day). Participants completed standardized self-report measures of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity after lamotrigine initiation and approximately biweekly thereafter. Mood and eating disorder symptomatology were measured at lamotrigine initiation and at time of final assessment.

Results

Lamotrigine and concurrent DBT were associated with large reductions in self-reported affective and behavioral dysregulation (ps < 0.01). Eating disorder and mood symptoms decreased moderately.

Conclusions

Although our findings are limited by the confounds inherent in an open series, lamotrigine showed initial promise in reducing emotional instability and behavioral impulsivity in severely dysregulated eating-disordered patients. These preliminary results support further investigation of lamotrigine for eating disorders in rigorous controlled trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bulimia nervosa (BN) and the binge-eating/purging subtype of anorexia nervosa (AN-BP) are characterized by loss-of-control eating and compensatory behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting) and are associated with significant medical morbidity and chronicity [1, 2]. Other impulsive behaviors, including non-suicidal self-injury, shoplifting, and drug and alcohol abuse, often are comorbid with these eating disorders [3,4,5]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been the mainstay of psychopharmacological treatment of BN since FDA approval of fluoxetine more than 20 years ago [6]. Although no medications are approved for AN-BP, SSRIs frequently are tried in these patients as well [7]. Still, first-line interventions, including both SSRIs and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), are ineffective for a large proportion of patients with BN and AN-BP who have been described as “multi-impulsive,” and struggle with a range of dysregulated behaviors [8,9,10,11,12].

A growing body of evidence suggests that these dysregulated behaviors may be linked to emotional instability, and that pervasive deficits in cognitive and behavioural self-regulatory control may contribute to eating disorder behaviors and inadequate response to existing eating disorder treatments [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Self-reported emotion regulation problems have been associated with eating disorder cognitions and compensatory behaviors in BN [13]. Further, increasing negative affect and decreasing positive affect often precede binge eating and purging [20,21,22,23], and affective instability is associated with more frequent weight loss behaviors in AN [24] and more frequent bulimic behaviors in BN [25]. Extreme increases in negative affect are less likely after bulimic behaviors, but average affective instability is worse after bulimic episodes in BN [26]. As such, the powerful but only temporary relief of dysregulated and impulsive behaviors may ultimately reinforce maladaptive cycles [27], and affect dysregulation may contribute to AN-BP, BN, and bulimic symptoms more broadly. These data suggest that directly targeting regulatory deficits may be key to more effective treatment.

Mood-stabilizing medications have been shown to reduce affective and behavioral dysregulation in other psychiatric populations. One such medication is lamotrigine, an antiepileptic drug. It has received FDA indication [28] for maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder to delay the time to occurrence of mood episodes, and it is used widely for bipolar II disorder and unspecified bipolar and related disorders [29]. Lamotrigine also has shown promise in the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD) [30, 31]. Data from two small randomized-controlled trials in BPD indicated that lamotrigine was superior to placebo in reducing anger [32], affective instability, and impulsivity (including symptoms of BN) [33]. A much larger multi-center RCT of lamotrigine for long-term treatment of BPD is in progress [34].

Consistent with the literature, our clinical experience is that severely dysregulated eating-disordered patients often show little or no response to antidepressant monotherapy, and in some cases, they appear to become more agitated with this treatment. This led us to speculate that medications with mood-stabilizing properties [32,33,34] may be a better alternative for some. We previously reported a positive response to lamotrigine in five patients with eating disorders characterized by bulimic symptoms and significant affective and behavioral dysregulation [35]. Though encouraging, these case reports were based on personal observation. To support a potential future controlled trial of lamotrigine, the current study aimed to confirm our observations in a larger series of patients, utilizing standardized instruments [36, 37] designed to assess changes in affective and behavioral dysregulation in response to treatment, as well as mood and eating disorder symptomatology.

Methods

Participants

Participants enrolled in this open trial were female patients in the UCSD Eating Disorders Program deemed appropriate for lamotrigine initiation (n = 14) based on presence of pervasive emotion dysregulation, poor impulse control, and endorsed binge eating and/or purging, as clinically assessed by the program psychiatrists. All enrolled patients had a prior history of inadequate response to treatment with antidepressants. Upon entering the study, patients were continued on other current medications where considered appropriate by the psychiatrist (for example, if there had been a partial response, or for treatment of co-morbid conditions). Participants included in this report took lamotrigine for a minimum of 60 days. This is because lamotrigine requires a very gradual titration for safety reasons (see Discussion), so significant results may take longer to realize than in most medication trials.

Procedure

Lamotrigine titration

Participants started at a dose of 25 mg/day for two weeks, then increased to 50 mg/day for the next two weeks. Subsequent rate of titration was variable, with a maximum increase of 50 mg/day every two weeks until reaching a therapeutic dose (expected range from 100 mg/day to 300 mg/day). Increases and maximum dose were determined by the psychiatrist based on tolerability and therapeutic response.

Additional treatment as usual

All participants entered treatment at the partial hospital program (PHP) level (10 h per day, six days per week). With clinical improvement, patients stepped down to 6 h per day at the PHP level, and ultimately to 4 h per day, three days per week in the intensive outpatient program (IOP). All patients received Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [38], adapted for the PHP/IOP setting, throughout their course of treatment at UCSD. This included weekly individual DBT sessions, twice weekly skills training groups using the DBT Skills manual [39], other groups based on DBT principles (e.g., behavioral chain analysis), and skills coaching via phone or text messaging outside of program hours. All therapists participated in a weekly DBT consultation team [38].

The Human Research Protections Program at the University of California, San Diego approved of the collection of data for this study. All participants provided written informed consent before completing assessments and consented to treatment including psychotropic medication.

Measures

Participants completed assessments of emotional and behavioral dysregulation at baseline and approximately every two weeks thereafter (mean time between assessments = 20.5 days, SD = 12.9 days) for up to seven additional time points after lamotrigine initiation. Our primary outcome measures were well-validated assessments of weekly changes in cognitive, affective, and behavioral dysregulation, which originally were designed to track symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD):

Borderline evaluation of severity over time (BEST) [36]

The BEST was developed to rate the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors typical of BPD The scale includes 15 items and three subscales. Eight items assess cognitive and affective dysregulation, four items assess behavioral dysregulation, and three items assess skillful behavioral regulation. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5. The BEST has been shown to have good to excellent internal consistency, both in individuals with BPD and a comparison sample, and moderate test-retest reliability [36].

Zanarini rating scale for borderline personality disorder (ZAN-BPD) [40]

The ZAN-BPD is a clinician-administered scale for the assessment of change in borderline psychopathology over a 2-week time period. Each of the nine criteria for BPD is rated on a 5-point anchored rating scale of 0 to 4, yielding a total score of 0 to 36. The ZAN-BPD includes three items assessing affective dysregulation, two items assessing cognitive dysregulation, two items assessing impulsive [41] behaviors, and two items assessing unstable interpersonal relationships. For feasibility reasons, the ZAN-BPD was administered as a self-report questionnaire; however, the clinician-administered version of the ZAN-BPD has shown good internal consistency, with test-retest reliability in the good to excellent range [40].

Secondary outcome measures, administered at treatment initiation and at the time of final assessment, included ratings of eating disorder symptom severity, anxiety, and depression:

Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) [41]

The EDE-Q is a 36-item self-report questionnaire adapted from the investigator-based Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) [42]. The EDE-Q consists of four subscales, including Restraint, Shape Concern, Weight Concern, and Eating Concern, and assesses eating disorder symptomatology during the past 28 days. Items of all four subscales were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 6. The EDE-Q subscales have demonstrated acceptable internal consistency and good test-retest reliability and convergent and discriminant validity [43, 44].

State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) [45]

The STAI is a 40-item self-report measure, including 20 items assessing trait anxiety and 20 assessing state anxiety. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. The STAI has been shown to have excellent internal consistency in large samples [46].

Beck depression inventory (BDI-II) [47]

The BDI-II is a self-report questionnaire that measures severity and symptoms of depression. The questionnaire includes 21 items, and items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depression. The BDI-II has demonstrated excellent internal consistency and high convergent validity [48], as well as excellent test-retest reliability [49].

Statistical analysis

Related-samples Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to examine changes from baseline to end of treatment in BEST and ZAN-BPD scores. Average BEST and ZAN-BPD scores did not differ across diagnoses; therefore, diagnosis was not included in the final models. Cohen’s d [50] was calculated to measure effect size and estimate the magnitude of lamotrigine effectiveness in this sample. Additionally, a reliable change index (RCI) [51] was used to determine whether the symptom reductions measured by the BEST and the ZAN-BPD were clinically significant and statistically reliable (RCI cut-off: ≥ 1.96). RCI was calculated for each patient (the difference between baseline and final assessment score divided by the standard error of difference between the two scores) on the BEST and the ZAN-BPD. In exploratory analyses, related-samples Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to examine changes from baseline to end of treatment in eating disorder, depression, and anxiety scores.

Results

Participants

Of the 14 participants initially enrolled in this open trial, five were excluded from analyses because they did not complete 60 days of lamotrigine treatment and self-report assessments (Fig. 1). The nine participants who were treated for 60 or more days (Table 1) were women ranging in age from 18 to 42 years (M = 30.1 years, SD = 7.8), with a mean intake BMI of 22.6 kg/m2 (SD = 3.3). Average length of time on lamotrigine was 147.4 days (SD = 78.9). Mean dose at time of final assessment was 161.1 mg/day (SD = 48.6), with a range of 100 mg/day to 200 mg/day. Baseline characteristics and medication information for each individual are presented in Table 1. In most instances, titrations of concurrent medications were complete before initiation of lamotrigine. In three cases, other medications were changed over the course of lamotrigine treatment. One patient changed antidepressants (duloxetine was replaced with sertraline and subsequently discontinued; see Table 1 footnote), and two patients discontinued other medications (one patient discontinued naltrexone, bupropion XL, and trazodone during her first 2–3 months in the program; one patient discontinued trazodone during her first 1–2 months in the program).

CONSORT Flow Diagram for Lamotrigine Open Trial. Out of 14 enrolled patients, five were discontinued from the trial: one patient stopped lamotrigine after she developed a possible rash, one non-adherent participant reported to psychiatrists several months into the trial that she never started taking lamotrigine, and three were lost to follow up after discharging prematurely from our program. As none of the five discontinued patients completed 60 days of lamotrigine titration, they were excluded from the analysis. The final sample included nine patients who started lamotrigine at UCSD and took the medication for at least 60 days

Average length of stay in the eating disorders program (including both PHP and subsequent IOP) was 186 calendar days (SD = 39.72). During admission, the patients spent an average of 82.30 days (SD = 34.12) attending treatment groups at our facility (as noted previously, patients attended for 3–6 days during each calendar week, depending upon level of care). Four of the nine patients included in the analyses completed follow-up assessments after discharge. These patients were discharged from the treatment program on lamotrigine day 124, 162, 69, and 56. Three of these four participants completed 3-month follow-up assessments, and one completed a 6-month follow-up assessment.

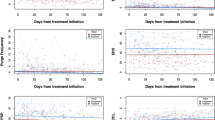

Changes in affective and behavioral dysregulation

BEST and ZAN-BPD scores over time are plotted in Fig. 2. Pre- to post-treatment reductions in dysregulation as measured by the BEST (z = 2.670, p = 0.008) and ZAN-BPD (z = 2.666, p = 0.008) were statistically significant (Table 2). At one month of lamotrigine treatment, BEST score reduction was very large (d = 2.41) and ZAN-BPD score reduction was moderate to large (d = 0.78). As depicted by the graphs in Fig. 2, patients appeared to continue improving several months into lamotrigine treatment with further dose titration. Effect sizes for baseline to end-of-assessment reductions on the ZAN-BPD (Cohen’s d = 1.53) and on the BEST (Cohen’s d = 2.29) were very large.

BEST and ZAN-BPD Score Change Over Time. The Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST) score change over time is presented in panel a and the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) score change is shown in panel b. Days on lamotrigine at each assessment point are shown on the x axis and scores are shown on the y axis

Most of the patients (77.8%) showed a clinically significant and reliable treatment response (RCI > 1.96) as measured by the ZAN-BPD (mean RCI = 4.46, SD = 3.34), and roughly half (55.6%) of the patients showed a clinically significant and reliable treatment response as measured by BEST scores (mean RCI = 2.26, SD = 0.96).

Changes in mood, anxiety, and eating disorder symptoms

Results of exploratory analyses examining changes in other symptoms are presented in Table 2. Despite medium to large reductions in EDE-Q Restraint (d = 1.21), Eating Concern (d = 0.45), Shape Concern (d = 0.99), and EDE-Q Global (d = 0.82) scores, these pre- to post-treatment differences did not reach statistical significance. Reductions in depression scores were small to medium (0.46), but changes in anxiety scores were negligible.

Discussion

This is the first study to use standardized measures of affective and behavioral dysregulation to document lamotrigine response in eating-disordered patients over a substantial time period. Lamotrigine and concurrent DBT were associated with significant and medium to large self-reported reductions in dysregulated emotions and problems with impulse control. Further, in our small sample, we found preliminary evidence of reduced eating disorder symptoms and depression, but little change in anxiety symptoms. Because patients received multimodal eating disorder treatment during lamotrigine titration, these data cannot isolate the effects of the medication. However, our preliminary findings suggest that the targeted effects of lamotrigine in eating disorder populations warrant further investigation.

Our results are consistent with prior reports of lamotrigine treatment benefit for some patients with BN- and AN-BP-spectrum disorders [35, 52, 53] and for some patients with binge-eating behaviors [54]. As noted previously, lamotrigine is utilized in other conditions characterized by dysregulated mood and poor impulse control, including bipolar disorder and BPD. When used in bipolar disorder, it is most notably effective in reducing depressive symptoms [29]. This ability to stabilize mood with potentially greater impact on depression [55,56,57] may account for our exploratory and very preliminary findings of moderate reductions in depressive symptoms for some eating-disordered patients.

The literature on affective instability suggests some blurring of categorical lines between these diagnoses. While it is known that bipolar disorder and BPD can co-exist, and that patients with bipolar disorder alone may display affective dysregulation not unlike that in BPD [58, 59], more recent real-time data collection suggests a similar type of affective instability in patients with BN, supporting the possibility of a transdiagnostic rather than disorder-specific mechanism [60]. Although determining a specific DSM diagnosis for the dysregulated characteristics of eating-disordered patients can be difficult, previous reports have suggested that up to 68% of those with eating disorders may have bipolar disorder if the so-called “soft spectrum” is included [61,62,63]. Additionally, 14% to 35% of patients with BN are believed to have BPD [64,65,66,67]. Finally, up to 50% of individuals across the range of eating disorders are estimated to abuse alcohol or other illicit substances [4, 5]. Not uncommonly, patients with AN-BP and BN-spectrum disorders struggle with a combination of these problems. Clinical evaluation by our psychiatrists (MET, UFB) suggested that although participants reported significant difficulties with mood regulation and impulse control, most did not meet full criteria for BPD diagnosis. Self-report measures assessed changes in affect regulation and impulse control in response to treatment, but diagnostic category was not included in study entry criteria nor was it a measure of treatment response. Administration of structured research interviews to assess for personality disorders was not feasible in our clinical setting. Future studies should include structured diagnostic interviews to determine the impact of lamotrigine on dysregulation in eating-disordered individuals with and without comorbid BPD.

Lamotrigine appears to be acceptable to many patients because of its typically low side effect burden [68] and reported weight neutrality (the latter of which may be extremely important for medication adherence in those with eating disorders). Although lamotrigine usually is well-tolerated, as was the case in our trial, there are precautions to be followed and occasional drawbacks with its use. The most common potential side effects include benign rash (up to 10%), headache, nausea, insomnia, somnolence, fatigue, dizziness, blurred vision, ataxia, tremor, rhinitis, and abdominal pain. One of our 14 participants discontinued because of a possible benign rash, which is the most frequent cause of discontinuation of lamotrigine in general [69]. This is because if any skin eruption is suspected of being a drug-induced rash, the medication should be stopped, with the usual recommendation that it not be retried in the future. Such precautions are taken because a rare but very serious adverse effect of lamotrigine is the rash of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and epidermal necrolysis [70]. In studies with epilepsy patients, incidence of Stevens-Johnson syndrome varied between 0.08% and 0.3% in adults [69]. A slow titration is necessary to minimize the risk of rash, which may substantially delay optimal effects for some patients. As an additional dosing consideration, the patients in our trial were not taking oral contraceptives, but it is important to keep in mind that these medications can decrease concentrations of lamotrigine [71].

Lamotrigine is a glutamate antagonist, believed to stabilize mood by inhibiting release of this excitatory neurotransmitter [57]. Our findings raise the question as to whether glutamatergic abnormalities play a role in affective and behavioral dysregulation in individuals with eating disorders as they may in bipolar disorder and BPD [72, 73]. This could help explain why traditionally-used serotonergic antidepressant monotherapy has limited impact for many patients with AN-BP- and BN-spectrum disorders.

Lamotrigine may specifically target corticolimbic circuit alterations that contribute to affective dysregulation. Several functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have suggested that relative to healthy controls, individuals with bipolar disorder, BPD and BN all show increased amygdala activation and decreased activation in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in response to negative emotional stimuli [74,75,76]. Successful modulation of emotional responses is partially dependent on adequate DLPFC and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) signalling [77]. In healthy individuals, lamotrigine, in combination with prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation, increases prefrontal circuit connectivity [78]. Functional imaging studies in bipolar disorder similarly suggest lamotrigine response is associated with increased PFC activation and decreased amygdala activation to negatively-valenced emotional stimuli [79, 80]. These corticolimbic changes are believed to be mediated by a reduction in glutamate [57, 81]. Research integrating fMRI with positron emission tomography is needed to test this hypothesis in eating disorders.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, almost all of the patients concurrently were taking other medication, most notably antidepressants. Therefore, it is not possible to isolate the effects of lamotrigine relative to other medications. Second, and perhaps the greatest confounding factor, was the comprehensive concurrent DBT treatment and/or the structure provided by a PHP/IOP. The design of this pilot study cannot parse the relative impact of these other aspects of treatment from those of lamotrigine. Third, all of our patients were female, and future study in male patients is needed. Fourth, we did not assess plasma levels of lamotrigine. Finally, effect size for changes in depression and anxiety also may have been impacted by the second and final assessment time point for these measures occurring near the date of program discharge for the majority of patients. These final assessment scores may reflect 1) temporarily worsened depression and anxiety, as the uncertainties and insecurities associated with treatment termination may be particularly pronounced in patients who struggle with emotion regulation [82], or 2) increased emotional awareness with DBT, which can elevate depression and anxiety scores despite reduction in behavioral symptoms [83, 84].

Despite these limitations, our pilot open series has important strengths. Many of the participants had a history of multiple unsuccessful medication trials, all had been poorly responsive to antidepressant monotherapy before entering the trial, and, anecdotally, they often described an improved ability to utilize DBT and other emotion regulation strategies during and following titration of lamotrigine specifically. Furthermore, 7 of the 9 patients (77.8%) had prior exposure to DBT and all had prior exposure to structured treatment either in our program or at other locations prior to lamotrigine initiation. Although this included high levels of care for most (residential or inpatient treatment for 8 out of 9 patients), none had shown significant improvement from those factors alone.

The treatment effect as measured by the ZAN-BPD was comparable to that observed in a prior trial of lamotrigine (d = 1.40; [33]) and the treatment effect as measured by the BEST was superior to that reported in a trial of Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (d = 0.50; [36]). In addition, aspects of our data very preliminarily suggest a potential added benefit of lamotrigine: Four patients included in our sample continued to show symptom improvement after discharge (i.e., after completing concurrent intensive DBT).

Conclusion and future directions

In summary, our initial data support further study of lamotrigine for the treatment of dysregulation in eating-disordered patients. Results from our small sample must be interpreted with caution. It is premature to propose that lamotrigine is a treatment for dysregulated mood and impulse control in eating disorders. Nevertheless, our findings preliminarily suggest that directly targeting regulatory deficits may be key to more effective treatment and support the feasibility of studying lamotrigine efficacy in eating-disordered populations. Our pilot findings are perhaps most important in supporting the need for large-scale, rigorously controlled investigations of lamotrigine, used with or without concurrent DBT or other therapies, to elucidate how these factors might interact to treat dysregulated behavior in eating disorders.

Abbreviations

- AN:

-

Anorexia nervosa

- AN-BP:

-

Anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging type

- BDI-II:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- BEST:

-

Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

- BPD:

-

Borderline personality disorder

- DBT:

-

Dialectical behavior therapy

- DLPFC:

-

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- EDE:

-

Eating Disorder Examination

- EDE-Q:

-

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire

- EDNOS:

-

Eating disorder not otherwise specified

- fMRI:

-

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

- IOP:

-

Intensive outpatient program

- PHP:

-

Partial hospital program

- RCI:

-

Reliable change index

- SSRI:

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- STAI:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- VMPFC:

-

Ventromedial prefrontal cortex

- ZAN-BPD:

-

Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fourth Edition - Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). 2000.

Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. Eating disorders and comorbidity: empirical, conceptual, and clinical implications. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(3):381–90.

Rosval L, Steiger H, Bruce K, Israel M, Richardson J, Aubut M. Impulsivity in women with eating disorders: problem of response inhibition, planning, or attention? Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(7):590–3.

Gregorowski C, Seedat S, Jordaan G. A clinical approach to the assessment and management of co-morbid eating disorders and substance use disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:289. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-289.

Harrop E, Marlatt G. The comorbidity of substance use disorders and eating disorders in women: prevalence, etiology, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):392–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.016.

Prozac Prescribing Information. on ww.fda.gov.

Yager J, Devlin M, Halmi K, Herzog D, Mitchell J, Powers P, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, Third Editionj. American Psychiatryc Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders Compendium, Arlington VA. 2006:1097–222.

Halmi K. Perplexities of treatment resistance in eating disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:292. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-292.

Mitchell J, Agras S, Wonderlich S. Treatment of bulimia nervosa: Where are we and where are we going? Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(2):95–101.

Rossiter EM, Agras WS, Telch CF, Schneider JA. Cluster B personality disorder characteristics predict outcome in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13(4):349–57.

Wilson G, Grilo C, Vitousek K. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychologist. 2007;62(3):199–216.

Racine S, Wildes J. Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of anorexia nervosa: the unique roles of lack of emotional awareness and impulse control difficulties when upset. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(7)

Lavender J, Wonderlich SA, Peterson C, Crosby R, Engel S, Mitchell J, et al. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22(3):212–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2288.

Lavender J, Wonderlich S, Engel S, Gordon K, Kaye W, Mitchell J. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;40:111–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.010.

Brockmeyer T, Skunde M, Wu M, Bresslein E, Rudofsky G, Herzog W, et al. Difficulties in emotion regulation across the spectrum of eating disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):565–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.001.

Svaldi J, Griepenstroh J, Tuschen-Caffier B, Ehring T. Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: a marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Res. 2012;15(197):103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.009.

Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J. Emotional functioning in eating disorders: attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1887–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000036.

Berner L, Marsh R. Frontostriatal circuits and the development of bulimia nervosa. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;17(8):395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00395. eCollection 2014

Marsh R, Steinglass J, Gerber A, Graziano O'Leary K, Wang Z, Murphy D, et al. Deficient activity in the neural systems that mediate self-regulatory control in bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):51–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.504.

Alpers G, Tuschen-Caffier B. Negative feelings and the desire to eat in bulimia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2001;2(4):339–52.

Berg K, Crosby R, Cao L, Peterson C, Engel SM, Jewonderlich S. Facets of negative affect prior to and following binge-only, purge-only, and binge/purge events in women with bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(1):111–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029703.

Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B. Maintenance of binge eating through negative mood: a naturalistic comparison of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(6):521–30.

Smyth J, Wonderlich S, Heron K, Sliwinski M, Crosby R, Mitchell J, et al. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. J Cons Clin Psychol. 2007;75(4):629–38.

Selby E, Cornelius T, Fehling K, Kranzler A, Panza E, Lavender J, et al. A perfect storm: examining the synergistic effects of negative and positive emotional instability on promoting weight loss activities in anorexia nervosa. Front Psychol. 2015;31(6):1260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01260.

Anestis M, Selby E, Crosby R, Wonderlich S, Engel S, Joiner T. A comparison of retrospective self-report versus ecological momentary assessment measures of affective lability in the examination of its relationship with bulimic symptomatology. Behav Res & Ther. 2010;48(7):607–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.012.

Berner L, Crosby R, Cao L, Engel S, Lavender J, Mitchell J, et al. Temporal associations between affective instability and dysregulated eating behavior in bulimia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. In Press

Cyders M, Smith G. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(6):807–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013341.

Lamictal Prescribing Information. on www.fda.gov.

Watanabe Y, Hongo S. Long-term efficacy and safety of lamotrigine for all types of bipolar disorder. Neuropschiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:843–54. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S128653.

Silk K. Management and effectiveness of psychopharmacology in emotionally unstable and borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(4):e524–e5. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14com09534.

Abraham P, Calabrese J. Evidenced-based pharmacologic treatment of borderline personality disorder: a shift from SSRIs to anticonvulsants and atypical antipsychotics? J Affect Disord. 2008;11(1):21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.024.

Tritt K, Nickel C, Lahmann C, Leiberich P, Rother W, Loew T, et al. Lamotrigine treatment of aggression in female borderline-patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(3):287–91.

Reich DB, Zanarini MC, Bieri K. A preliminary study of lamotrigine in the treatment of affective instability in borderline personality disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(5):270–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832d6c2f.

Crawford M, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, Byford S, Cunningham G, Gakhal K, et al. Lamotrigine versus inert placebo in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation. Trials. 2015;16:308. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0823-x.

Trunko M, Schwartz T, Marzola E, Klein A, Kaye W. Lamotrigine use in patients with binge eating and purging, significant affect dysregulation, and poor impulse control. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(3):329–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22234.

Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, McCormick B, Allen J, Black D. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord. 2009;23(3):281–93. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.281.

Zanarini M, Weingeroff J, Frankenburg F, Fitzmaurice G. Development of the self-report version of the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder. Personal Ment Health. 2015;9(4):243–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1302.

Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

Linehan M. DBT Skills Training Manual, Second Edition. Guilford Press, New York. 2015.

Zanarini M. Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Personal Disord. 2003;17(3):233–42.

Fairburn C, Beglin S. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0) C.G. Fairburn (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders, Guilford Press, New York (2008), pp. 309–313. 2008.

Fairburn C, Cooper Z, O'Connor M. Eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. 16th ed. New York: Guilford Press. p. 265–308, 2008.

Luce K, Crowther JH. The reliability of the eating disorder examination-self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:349–51.

Berg K, Peterson C, Frazier P, Crow S. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination-questionnaire: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(3):428–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20931.

Spielberger C, Luschene P, Vagg P, Jacobs A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.; 1983.

Ramanaiah N, Franzen M, Schill T. A psychometric study of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. J Pers Assess. 1983;47(5):531–5. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4705_14.

Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition. Manual: The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX; 1996.

Dozois D, Dobson K, Ahnberg J. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychol Assess. 1998;10(2):83–9. 1040–3590/9843.00.

Sprinkle SD, Lurie D, Insko S, Atkinson G, Jones G, Logan A, et al. Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. J Counseling Psychology. 2002;49(3):381. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.381.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc: Hillsdale, NJ, US; 1988. p. 474.

Jacobson N, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(1):12–9.

Rybakowski F, Kaminska K. Lamotrigine in the treatment of comorbid bipolar spectrum and bulimic disorders: case series. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):2004–5.

Marilov V, Sologub M. Comparative effectiveness of mood stabilizers in the complex therapy of bulimia nervosa. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2010;110(1):59–61.

Guerdjikova A, McElroy S, Welge J, Nelson E, Keck P, Hudson J. Lamotrigine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled monotherapy trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(3):150–8.

Amann B, Born C, Crespo J, Pomarol-Clotet E, McKenna P. Lamotrigine: when and where does it act in affective disorders? A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;10:1289–94.

Prabhavalkar K, Poovanpallil N, Bhatt L. Management of bipolar depression with lamotrigine: an antiepileptic mood stabilizer. Front Phramacol. 2015;6:242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00242.

Ketter T, Manji K, Post R. Potential mechanisms of action of lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(5):484–95.

Antoniadis D, Samakouri M, Livaditis M. The association of bipolar spectrum disorders and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Q. 2012;83(4):449–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-012-9214-6.

Renaud S, Corbalan F, Beaulieu S. Differential diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder type II and borderline personality disorder: analysis of the affective dimension. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(7):952–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.03.004.

Santangelo P, Reinhard I, Mussgay L, Steil R, Sawitzki G, Klein C, et al. Specificity of affective instability in patients with borderline personality disorder compared to posttraumatic stress disorder, bulimia nervosa, and healthy controls. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123(1):258–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035619.

Campos R, Dos Santos D, Cordas T, Angst J, Moreno R. Occurrence of bipolar spectrum disorder and comorbidities in women with eating disorders. Int J Bipiolar Disord. 2013;13(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/2194-7511-1-25.

McElroy S, Frye M, Hellemann G, Altshuler L, Leverich G, Suppes T, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in 875 patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(3):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.037.

McElroy S, Kotwal R, Keck P, Akiskal H. Comorbidity of bipolar and eating disorders: distinct or related disorders with shared dysregulations? J Affect Disord. 2005;86(2–3):107–27.

Inceoglu I, Franzen U, Backmund H, Gerlinghoff M. Personality disorders in patients in a day-treatment programme for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2000;8(67–72) https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0968(200002)8:1<67::AID-ERV326>3.0.CO;2-U.

Marañon I, Echeburúa E, Grijalvo J. Prevalence of personality disorders in patients with eating disorders: a pilot study using the IPDE. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2004;12:217–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.578.

Sansone R, Levitt J, Sansone L. The prevalence of personality disorders among those with eating disorders. Eating Disorders: The Journal of NeuroscienceTreatment & Prevention. 2005;13(1):7–21.

Zeeck A, Birindelli E, Sandhlz A, Joos A, Herzog T, Hartman A. Symptom severity and treatment course of bulimic patients with and without a borderline personality disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(6):430–8.

Stefan H, Feuerstein T. Novel anticonvulsant drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113(1):165–83.

Seo H, Chiesa A, Lee S, Patkr A, Han C, Masand P, et al. Safety and tolerability of lamotrigine: results from 12 placebo-controlled clinical trials and clinical implications. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(1):39–47.

Calabrese J, Sullivan J, Bowden C, Suppes T, Goldberg J, Sachs G, et al. Rash in multicenter trials of lamotrigine in mood disorders: clinical relevance and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(11):1012–9.

Patsalos P. Drug interactions with the newer antiepileptic drugs (AEDs)--Part 2: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between AEDs and drugs used to treat non-epilepsy disorders. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52(12):1045–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-013-0088-z.

Ehrlich A, Schubert F, Pehrs C, Gallinat J. Alterations of cerebral glutamate in the euthymic state of patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;233(2):73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.05.010.

Krause-Utz A, Winter D, Niedtfeld I, Schmahl C. The latest neuroimaging findings in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(3):438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0438-z.

Passarotti A, Sweeney J, Pavuluri M. Fronto-limbic dysfunction in mania pre-treatment and persistent amygdala over-activity post-treatment in pediatric bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2011;216(4):485–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2243-2.

Schulze LS, C Niedfeld I. Neural correlates of disturbed emotion processing in borderline personality disorder: A multimodal meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(2):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.027.

Townseld J, Torrisi S, Lieberman M, Sugar C, Bookheimer S, Altshuler L. Frontal-amygdala connectivity alterations during emotion downregulation in bipolar I disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):127–35.

Ochsner K, Silvers J, Buhle J. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1251:E1–E24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x.

Li X, Large C, Ricci R, Taylor JJ, Nahas Z, Bohning D, et al. Using interleaved transcranial magnetic stimulation/functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and dynamic causal modeling to understand the discrete circuit specific changes of medications: Lamotrigine and valproic acid changes in motor or prefrontal effective connectivity. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging. 2011;194(2):141–148. org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.04.012.

Jogia J, Haldane M, Cobb A, Kumari V, Frangou S. Pilot investigation of the changes in cortical activation during facial affect recognition with lamotrigine monotherapy in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(3):197–201. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037960.

Chang K, Wagner C, Garrett A, Howe M, Reiss A. A preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study of prefrontal-amygdalar activation changes in adolescents with bipolar depression treated with lamotrigine. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(3):426–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00576.x.

Frye M, Watzl J, Banakar S, O'Neill J, Mintz J, Davanzo P, et al. Increased anterior cingulate/medial prefrontal cortical glutamate and creatine in bipolar depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(12):2490–9.

McMain S, Korman L, Dimeff L. Dialectical behavior therapy and the treatment of emotion dysregulation. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(2):183–96.

Bardeen J, Fergus T. An examination of the incremental contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to health anxiety beyond specific emotion regulation strategies. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(4):394–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.002.

Carpenter R, Trull T. Components of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0335-2.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Karen Putnam (Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for her statistical consultation on this manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding, but preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIMH grant F32-MH108311 to Laura A. Berner.

Availability of data and materials

De-identified data available on reasonable request form the corresponding author.

Declarations

We also thank the staff at the UC San Diego Eating Disorders Center for Treatment and Research and the patients who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MET, TAS, and AC initially conceptualized and designed the study, with oversight from WHK and UFB. AC oversaw data collection, with the help of TN. LAB oversaw data cleaning, with the help of AC, TN, and JYC, and drafted the methods and results sections. MET wrote the initial draft and along with LAB, TAS, AC, UFB, JYC, and WHK revised the manuscript. All of the authors approved the manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Research Protections Program at the University of California, San Diego approved of the collection of data for this study. All participants provided written informed consent before completing assessments and consented to treatment including psychotropic medication.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Trunko, M.E., Schwartz, T.A., Berner, L.A. et al. A pilot open series of lamotrigine in DBT-treated eating disorders characterized by significant affective dysregulation and poor impulse control. bord personal disord emot dysregul 4, 21 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-017-0072-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-017-0072-6