Abstract

A subset of glioblastomas (GBMs) harbors potentially druggable oncogenic FGFR3-TACC3 (F3T3) fusions. However, their associated molecular and clinical features are poorly understood. Here we analyze the frequency of F3T3-fusion positivity, its associated genetic and methylation profiles, and its impact on survival in 906 IDH-wildtype GBM patients. We establish an F3T3 prevalence of 4.1% and delineate its associations with cancer signaling pathway alterations. F3T3-positive GBMs had lower tumor mutational and copy-number alteration burdens than F3T3-wildtype GBMs. Although F3T3 fusions were predominantly mutually exclusive with other oncogenic RTK pathway alterations, they did rarely co-occur with EGFR amplification. They were less likely to harbor TP53 alterations. By methylation profiling, they were more likely to be assigned the mesenchymal or RTK II subclass. Despite being older at diagnosis and having similar frequencies of MGMT promoter hypermethylation, patients with F3T3-positive GBMs lived about 8 months longer than those with F3T3-wildtype tumors. While consistent with IDH-wildtype GBM, F3T3-positive GBMs exhibit distinct biological features, underscoring the importance of pursuing molecular studies prior to clinical trial enrollment and targeted treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The molecular landscape of IDH-wildtype glioblastoma (GBM) has been extensively characterized, yet it remains a disease with a dismal prognosis [8, 9, 21]. Oncogenic fusions have recently been recognized as molecular drivers in a subset of IDH-wildtype GBMs. Approximately 3% of IDH-wildtype GBMs have been reported to harbor activating fusions involving the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene and the coiled-coil domain of the transforming acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 3 (TACC3) gene [39]. The FGFR3-TACC3 (F3T3) fusion protein is thought to promote malignant transformation by increasing downstream signaling through the MAPK pathway, activating mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism, and recruiting endogenous TACC3 away from the mitotic spindle, leading to delayed mitotic progression and aneuploidy [20, 37].

The relative rarity of F3T3-positive, IDH-wildtype GBM has hampered a full characterization of this molecular subset of GBM. While prior reports have suggested that these tumors may have recurrent histologic features and molecular profiles, including the absence of EGFR amplification and an increased frequency of CDK4 and MDM2 amplifications, extensive genomic characterization is lacking, particularly in the context of long-term clinical follow up and survival [7]. Further, since the discovery of F3T3 in GBM, DNA methylation-based tumor classification has emerged as a promising modality for improving diagnostic precision in neuropathology [10]. However, methylation profiles specific to F3T3-positive GBMs have not been reported. Further study of whether F3T3 fusions are associated with other genetic or epigenetic alterations may refine tumor subclassification efforts and impact prognosis and treatment.

The objective of this study was to describe the genomic landscape and methylation profiles of an unbiased institutional cohort of patients with F3T3-positive, IDH-wildtype GBMs and to identify potential associations with patient clinicopathologic characteristics and survival.

Materials and methods

Design, setting, and participants

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all patients diagnosed with IDH-wildtype GBMs between January 2015 and December 2019 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) in New York, NY. The study was approved by the MSK Institutional Review Board and reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [18].

Eligibility criteria

All patients with F3T3-positive GBMs were included in the study. All patients with F3T3-wildtype GBMs from the same period were selected for comparison. Cases with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations curated as oncogenic by the MSK OncoKB Precision Oncology Knowledge Base were excluded [14].

Diagnostic criteria

Cases were diagnosed by board-certified MSK neuropathologists (M.K.R., T.A.B.) according to the diagnostic criteria specified in the 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System [28].

Systematic review and meta-analysis of FGFR3-TACC3 fusion prevalence

The prevalence of F3T3 positivity identified among the IDH-wildtype GBMs by MSK-IMPACT (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets) in this study was synthesized with previously published estimates using random effects meta-analysis according to a previously reported method [31, 36].

DNA-based molecular analyses

To assess for the presence of FGFR3 fusions and other molecular alterations, tumors and matched normal blood samples were analyzed with the MSK-IMPACT next-generation DNA sequencing platform that targets up to 468 genes and select introns to produce data on single nucleotide variants, small insertions and deletions, copy number variation, and structural variants [16, 42]. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was defined as the number of mutations per megabase (mt/Mb).

Methylation-based molecular analyses

A subset of cases was analyzed with the Infinium MethylationEPIC (850K) platform, which provides MGMT promoter hypermethylation status as well as data on > 850,000 CpG methylation sites across the genome [3, 6]. Cases were assigned methylation-based classes using version 0.1.124 of the random forest-based mnp.v11b4 R package obtained from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) [10]. To investigate possible differences in methylation profiles between F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype GBMs, dimensionality reduction with principal component analysis and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding was performed and overlaid on a reference cohort of GBMs from the previously published DKFZ study using version 0.15 of the Rtsne package with the following non-default parameters: initial_dims = 100, max_iter = 1500, and theta = 0. Cross-reactive, sex-chromosome, and failed probes were excluded from these analyses.

Copy number alteration-based cytogenetic analyses

In addition to providing data on methylation profiles, the Infinium platform provides high resolution copy-number variant data similar to that provided by conventional whole-genome copy-number microarray. The chromosome- and arm-level cytogenetic profiles of the GBMs with F3T3 fusions were assessed using version 1.20.0 of the conumee-based MNPcnvplot function in the mnp.v11b4 package in R [26]. The overall tumor copy-number alteration burden (TCB), defined as the percentage of the analyzed genome for which the copy number was not equal to two, was also assessed using the larger MSK-IMPACT dataset. Tumor ploidy was also inferred from the tumor and matched germline MSK-IMPACT sequencing data using the previously validated FACETS algorithm [38].

Clinical data and survival analyses

Clinical charts were reviewed to extract data on age, sex, date of initial pathologic diagnosis, survival time, history of radiotherapy with or without concurrent temozolomide (TMZ), and treatment history. Reported MGMT promoter hypermethylation status, typically determined by pyrosequencing, was extracted from the electronic medical record for those patients who did not undergo methylation analysis on the Infinium platform [32]. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnostic biopsy until the time of death due to any cause.

Statistical analyses

Differences in sample means were assessed using the unpaired Student’s t test. Differences in sample medians were assessed using the unpaired Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test. Differences among categorical variables were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Binomial proportion confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method. Clinical and pathological variables were examined in univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for associations with overall survival. The multivariate models were adjusted for potential confounders including age, sex, race, and MGMT status. Genomic data were accessed using the internal MSK cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics and statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) [13, 22, 35]. Statistical tests were 2-sided and used a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Reported p values were not adjusted for multiple testing.

Results

Description of the cohort

Between January 2015 and December 2019, samples from 906 patients with IDH-wildtype GBMs underwent DNA sequencing with MSK-IMPACT (Fig. 1). In all, 4.1% (37/906) exhibited F3T3 fusions, 0.2% (2/906) exhibited non-canonical fusions involving FGFR3 (one each of FGFR3-ST7L and FGFR3-PTBP1, which are excluded from further analyses since dimerization domains have not been reported in these 3′ partner genes [44]), and 95.7% (867/906) had no fusions involving FGFR3. The F3T3 gene fusions most commonly involved FGFR3 exons 17 (67.6% [25/37]) or 18 (29.7% [11/37]) and TACC3 exons 11 (37.8% [14/37]) or 10 (24.3% [9/37]) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Flow diagram of specimen selection. Note: The two tumors with non-canonical fusions were excluded from further analyses because dimerization domains have not been reported in these 3′ partner genes [44]

Patients with F3T3-positive tumors in this cohort were significantly older at diagnosis, with a mean age of 63.6 years (interquartile range [IQR], 57.2–72.2) compared to 59.4 years (IQR, 52.0–68.1) for patients with F3T3-wildtype tumors (p = 0.02) (Table 1). The sex composition of the two groups was similar (40.5% [15/37] vs. 39.6% [343/867] female, p = 0.96). There was no difference in laterality or anatomic localization (p > 0.05 for both comparisons). All tumors were reviewed by a board-certified neuropathologist and found to meet histologic criteria for GBM, WHO grade IV (i.e., highly cellular and variably anaplastic glial cells with brisk mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and/or necrosis) [28].

Prevalence of FGFR3-TACC3 fusions compared to previously published studies of IDH-wildtype GBMs

The 4.1% (37/906) prevalence of F3T3 fusions identified in this study was compared to prevalence estimates reported in six previously published studies [2, 5, 17, 33, 34, 39]. Taken together, the previously published studies involved a total of 883 IDH-wildtype GBMs (median, 68.5; range 17–584). Meta-analytic pooling of the prevalence value from the present study with those from the six previously published studies yielded a summary F3T3-fusion prevalence of 3.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9–4.7%), with no evidence of between-study heterogeneity (Q = 8.8, τ2 = 0, I2 = 0%, p = 0.18) (Fig. 2). The prevalence estimates reported by the individual studies ranged from 1.3 to 11.8%. Sensitivity analysis, in which the meta-analysis was serially repeated after exclusion of each study, demonstrated that no individual study affected the overall estimate by more than 0.4%. Thus, we conclude that the prevalence of F3T3 fusions in IDH-wildtype GBMs is approximately 4%.

Systematic review and meta-analysis of FGFR3-TACC3 fusion prevalence among IDH-wildtype glioblastomas. Note: The vertical dashed line indicates the pooled summary estimate (95% confidence interval [CI]) for all studies. The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs of the estimate. The studies are listed in chronological order of publication

Associations between FGFR3-TACC3 fusions and canonical drivers of glioblastoma tumorigenesis

The relative frequencies of selected mutations and copy-number alterations curated as potentially oncogenic in OncoKB [14] and/or as putative driver alterations in the Cancer Hotspots [15] database in the RTK/RAS/MAPK, PI3K, P53, cell cycle, and telomere maintenance pathways among the 37 F3T3-positive GBMs are presented in Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Fig. S2. F3T3-positive tumors had significantly lower median TMB than F3T3-wildtype GBMs (3.0 mt/Mb [IQR, 2.6–3.5] vs. 3.9 mt/Mb [IQR, 3.0–5.3], p = 0.001), a difference that persisted after exclusion of cases with hypermutation (TMB ≥ 20 mt/Mb) secondary to TMZ therapy (Fig. 4a).

Tumor mutational burden (a), copy-number burden (b), and FACETS-derived tumor ploidy (c) stratified by FGFR3-TACC3 fusion status. Note: The violin plot is a box plot with a rotated kernel density plot on each side. The plot allows the reader to visualize the median, interquartile range, range, and distribution of the data

Between-group differences in oncogenic somatic mutations and copy-number alterations among the non-hypermutated F3T3-positive (n = 36) and F3T3-wildtype (n = 844) cases were compared (Fig. 5). F3T3 fusions were predominantly mutually exclusive with other oncogenic alterations in the RTK pathway. F3T3-positive cases were less likely to exhibit concurrent EGFR amplification (5.6% [2/36] vs. 43.4% [366/844], p < 0.001) or mutation (2.8% [1/36] vs. 18.1% [153/844], p < 0.01) and were mutually exclusive with PDGFRA (0% [0/36] vs. 11.6% [98/844], p = 0.03), KIT (0% [0/36] vs. 7.5% [63/844], p = 0.10), and MET amplification (0% [0/36] vs. 2.1% [18/844], p = 1.0). Conversely, they were more likely to exhibit concurrent FGFR3 amplification (30.6% [11/36] vs. 0.4% [3/844], p < 0.001). An additional 52.8% (19/36) had evidence of low-level gains in FGFR3 consistent with the tandem duplication event that forms the F3T3 fusion product [34].

Differences in copy-number alterations (a) and mutations (b) among glioblastomas with and without FGFR3-TACC3 fusions. Legend: The scatterplot shows statistical significance (−log10 of p value) versus magnitude of change (log2 of fold change) for copy-number altered (a) and mutated (b) genes. The horizontal dashed line indicates a p value of 0.05. The vertical dashed lines indicate fold changes of 1.5. Positive fold changes indicate that the alterations are more common in FGFR3-TACC3 positive tumors, and vice versa

The proportion of downstream RAS/MAPK alterations in the F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype groups was also examined. There was no significant difference in the frequency of NF1 inactivation (25.0% [9/36] vs. 17.2% [145/844], p = 0.26). BRAF mutations (0% [0/36] vs. 2.6% [22/844], p = 1.0) were not observed in F3T3-positive tumors. Similarly, oncogenic alterations in KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, RIT1, RASA1, and RAF1 were not identified in any of the F3T3-positive tumors and were only very rarely identified (< 1.0% of cases) in F3T3-wildtype tumors (p = 1.0 for all comparisons). The relative proportion of PI3K pathway alterations was similar, including the frequency of PIK3CA mutations (5.6% [2/36] vs. 9.5% [80/844], p = 0.57), PIK3R1 mutations (11.1% [4/36] vs. 8.9% [75/844], p = 0.56), and PTEN inactivation (44.4% [16/36] vs. 46.7% [394/844], p = 0.87).

F3T3-positive tumors were less likely to harbor certain P53 pathway alterations than F3T3-wildtype tumors. Specifically, F3T3-positive cases were significantly less likely to exhibit concurrent oncogenic alterations in TP53 (5.6% [2/36] vs. 30.9% [261/844], p < 0.001) and were mutually exclusive with amplifications in MDM4 (0% [0/36] vs. 6.9% [58/844], p = 0.16). The frequencies of MDM2 amplification (11.1% [4/36] vs. 8.5% [72/844], p = 0.54) and CDKN2A inactivation (55.6% [20/36] vs. 60.3% [509/844], p = 0.60) were similar.

The frequencies of cell cycle pathway alterations between the F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype groups did not substantially differ, including for RB1 inactivation (5.6% [2/36] vs. 13.2% [111/844], p = 0.30), CDKN2B inactivation (50.0% [18/36] vs. 56.9% [480/844], p = 0.49), CDKN2C inactivation (2.8% [1/36] vs. 4.1% [35/844], p = 1.0), CCND2 amplification (2.8% [1/36] vs. 1.5% [13/844], p = 0.44), CDK4 amplification (13.9% [5/36] vs. 13.9% [117/844], p = 1.0), and CDK6 amplification (0% [0/36] vs. 1.9% [16/844], p = 1.0).

There was no significant difference in the frequency of TERT promoter mutations (91.7% [33/36] vs. 88.2% [744/844], p = 0.79) between the F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype groups. Last, no F3T3-positive cases exhibited ATRX (0% [0/36] vs. 2.7% [23/844], p = 0.62) or H3F3A mutations (0% [0/36] vs. 1.7% [14/844], p = 1.0).

Methylation profiles of glioblastomas with and without FGFR3-TACC3 fusions

A subset of the F3T3-positive (91.9% [34/37]) and -wildtype (11.5% [100/867]) GBMs was analyzed on the Infinium platform [3] and classified using the Heidelberg methylation-based glioma classification tool [10]. There was no difference in the frequency of MGMT promoter hypermethylation between the F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype cases (52.9% [18/34] vs. 48.0% [48/100], p = 0.69). The Heidelberg tool confidently assigned classes to 88.2% (30/34) of the F3T3-positive tumors and 93.0% (93/100) of the F3T3-wildtype tumors (p = 0.47). F3T3-positive tumors were more likely to be assigned the mesenchymal or RTK II subclass (grouped together for this analysis due to their overlapping methylation characteristics) than were F3T3-wildtype tumors (96.7% [29/30] vs. 72.0% [67/93], p = 0.004) (Additional file 1: Table S1). The F3T3-positive mesenchymal and RTK II subclass tumors did not significantly differ with respect to median TMB (3.0 mt/Mb [IQR, 2.6–3.5] vs. 3.5 mt/Mb [IQR, 2.6–4.5], p = 0.93) or in TP53 alteration frequency (6.7% [1/15] vs. 14.3% [2/14], p = 0.60). Only one F3T3-positive case was assigned the RTK I subclass (3.3% [1/30]). In contrast, 14.3% (5/35) of EGFR-amplified cases tested and 50.0% (6/12) of PDGFRA-amplified cases tested were assigned the RTK I subclass. When stratified by F3T3-fusion status and considered alongside 446 previously published GBM methylation profiles from the Heidelberg cohort, dimensionality reduction with principal component analysis and t-distributed stochastic neighbor confirmed these findings (Fig. 6). F3T3-positive tumors were 2.0 × more likely (95% CI, 1.8–2.2, p < 0.0001) to be assigned to the mesenchymal or RTK II subclass and 0.1 × (95% CI, 0.01–0.5, p = 0.01) as likely to be assigned to any other subclass.

Dimensionality reduction demonstrated that FGFR3-TACC3 fusion-positive tumors were more likely to be assigned to the mesenchymal and RTK II methylation subclasses. Note: Cases were assigned DNA methylation-based classifications according to the method described by Capper et al. [10]. F3T3-positive GBMs overwhelmingly fell into the GBM, MES and GBM, RTK II clusters

Copy number alteration-based cytogenetic analysis of glioblastomas with and without FGFR3-TACC3 fusions

Among F3T3-positive tumors with analyzable data, 78.1% (25/32) had concurrent chromosome 7 gain and 10q loss, 9.4% (3/32) had chromosome 7 gain without 10q loss, 6.3% (2/32) had 10q loss without chromosome 7 gain, and 6.3% (2/32) had concurrent loss of 10q, 13q, and 14q, all consistent with the integrated diagnosis of IDH-wildtype GBM. The overall TCB was assessed using the larger MSK-IMPACT dataset that included all 904 patients. Because the F3T3 fusion protein is thought to cause aneuploidy, we hypothesized that F3T3-positive GBMs would have higher TCBs than F3T3-wildtype GBMs. Unexpectedly, F3T3-positive tumors had significantly lower TCBs. The median TCB for the F3T3-positive tumors was 15.0% (IQR, 10.4–17.5%) while that for the F3T3-wildtype tumors was 17.4% (IQR, 12.9–23.4%) (p = 0.006) (Fig. 4b). A similar finding was obtained using a subset (n = 371) of the MSK-IMPACT paired germline data in an allele-specific copy-number analysis of tumor ploidy using the FACETS algorithm [38], which revealed that F3T3-positive tumors had slightly lower median ploidy (2.06 × [IQR, 2.00–2.24] vs. 2.16 × [IQR, 2.05–2.32], p = 0.07) (Fig. 4c).

Clinical characteristics and overall survival

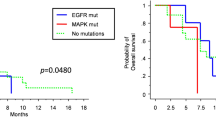

Follow-up data were sought for all patients through a comprehensive medical-record and obituary search. The median follow-up time was 55.6 months (IQR, 24.9–60.9) among F3T3-positive and 52.0 months (IQR, 19.8–92.9) among F3T3-wildtype patients (p = 0.9). In all, 64.9% (24/37) of F3T3-positive and 71.5% (620/867) of F3T3-wildtype patients died during follow up (p = 0.36). On univariate Kaplan–Meier analysis, F3T3-positive patients lived slightly longer than F3T3-wildtype patients (26.7 [IQR, 16.0–46.9] vs. 18.5 [IQR, 12.1–29.7] months, p = 0.07), corresponding to a hazard ratio of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.46–1.04) (Fig. 7). As expected, MGMT promoter hypermethylation was associated with improved survival on univariate analysis (29.2 [IQR, 17.2–57.1] vs. 16.3 [IQR, 11.3–23.5] months, p < 0.0001), corresponding to a hazard ratio of 0.43 (95% CI, 0.36–0.53). In a multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, race, and MGMT status, the hazard ratio for F3T3 positivity was 0.68 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.03, p = 0.07), similar to the association identified on univariate analysis.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival stratified by FGFR3-TACC3 fusion (a) and MGMT promoter hypermethylation (b) status. Note: Overall survival was defined as the time from initial diagnostic biopsy until the time of death due to any cause. Two-sided p values for difference were calculated using the log-rank test

Treatment of patients with FGFR3-TACC3 fusions

Treatment data were available for 91.9% (34/37) of the patients with F3T3-positive GBMs, all of whom received upfront radiotherapy and TMZ (concurrently and/or as adjuvant therapy). Only a minority of patients received a therapy targeting FGF/FGFR signaling. Specifically, 5.9% (2/34) received a selective FGFR inhibitor and 5.9% (2/34) received a multikinase inhibitor/non-selective FGFR inhibitor. The small number of patients receiving targeted therapy precluded investigating its association with overall survival.

Discussion

This genomic landscape study of 906 patients with IDH-wildtype GBMs treated at a tertiary cancer referral center demonstrated that 4.1% harbored potentially druggable activating F3T3 fusions with recurrent structural isoforms; characteristic associated mutational, copy-number, and methylation profiles; and clinical outcomes slightly better than patients with F3T3-wildtype tumors despite occurring in older individuals.

Our understanding of F3T3-positive GBMs has increased since the initial discovery that demonstrated F3T3 fusions comprised a rare yet recurrent oncogenic structural event resulting in an in-frame fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity and mitogenic effects, which were reversible by FGFR kinase inhibition [34, 39]. Together with subsequent studies involving a total 883 IDH-wildtype GBMs, it was previously estimated that 1–12% might harbor F3T3 fusions, with 3% a commonly cited prevalence estimate [2, 5, 17, 33, 34, 39]. The present study, involving a large, unbiased single-institutional cohort of 906 prospectively sequenced GBMs, revealed an F3T3-fusion prevalence of 4.1% among individuals with IDH-wildtype GBMs. Meta-analytic pooling suggested a similar prevalence, with an upper confidence interval indicating that as many as 5% of GBMs may have F3T3 fusions, slightly higher than suggested by prior consensus. Given ongoing interest in targeted FGFR3 inhibition, these data support the importance of pursuing comprehensive molecular characterization with robust fusion detection on all IDH-wildtype GBMs to identify patients for potential clinical trial enrollment and targeted treatment.

The present study confirms molecular features of F3T3-positive GBMs suggested in prior reports, including the diversity of structural isoforms of the F3T3 fusion gene itself. Prior studies established that isoforms involving FGFR3 exons 17 or 18 were most common [17, 34, 39], in agreement with our finding that 97.3% (36/37) of cases included one of these exons. As in prior studies, we found great variability for the 3′ TACC3 exon, ranging from exons 3–12. Overall, FGFR3 exon 17 to TACC3 exon 11 and FGFR3 exon 17 to TACC3 exon 10 fusions were most common.

However, our data reveal new insights into the molecular alterations associated with F3T3 fusions in IDH-wildtype GBMs, in some instances contrasting with prior smaller studies that employed more targeted sequencing methods. For example, prior reports suggested that the F3T3 fusion was mutually exclusive with EGFR, PDGFRA, or MET amplification [23, 34], and had an increased frequency of co-occurring CDK4 and MDM2 amplification [7, 17]. In the present study, F3T3-positivity was indeed mutually exclusive with amplification in PDGFRA or MET. Similarly, we found that F3T3-positive GBMs were less likely to exhibit concurrent EGFR amplification (5.6% vs. 43.3%); however, our data revealed that these events were not truly mutually exclusive, as two cases with F3T3 fusions exhibited bona fide amplification in EGFR. However, it is possible that the F3T3 fusion and the EGFR amplification events were present in different subclones, as has been shown for amplification of diverse RTKs [40, 41]. Further, there was no increased frequency of CDK4 or MDM2 amplification among F3T3-positive GBMs in our study.

The present study utilized a hybridization capture-based NGS assay (MSK-IMPACT) for sequencing all exons and selected introns of up to 468 genes with paired tumor-matched normal tissue analysis enabling unambiguous somatic mutation detection [16, 42], allowing us to comprehensively analyze oncogenic pathway alterations. A key negative finding gleaned from these data was a lack of significant differences in downstream PI3K, cell cycle, and telomere maintenance pathway alterations in F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype GBMs. Also interesting was the observation that oncogenic alterations in TP53 and MDM4 were less common among F3T3-positive tumors. Combined with the lower median TMB and TCB observed in F3T3-positive GBMs, these data suggest that F3T3-positivity itself may be enough to drive oncogenesis in the relative absence of other concurrent driver alterations. The relatively genomically quiet nature of the F3T3-positive GBMs was unexpected given that experimental data suggest that the F3T3 fusion protein recruits endogenous TACC3 away from the mitotic spindle, leading to delayed mitotic progression and aneuploidy [37]; our data therefore suggest that additional mechanisms to counteract this activity (e.g., the relative rarity of concurrent TP53 and MDM4 alterations identified in this study) may be engaged in vivo.

DNA methylation-based CNS tumor classification is becoming increasingly employed as a diagnostic tool in many neuropathology practices worldwide. The present study provides insight into the F3T3-positive GBM methylome using a previously validated machine-learning-based tumor classifier developed at University Hospital Heidelberg [10]. Aside from confirming the prior observation that MGMT promoter hypermethylation does not differ between F3T3-positive and F3T3-wildtype GBMs [17], the present analysis demonstrated that the majority of F3T3-positive GBMs can be accurately classified as IDH-wildtype GBMs by the Heidelberg classifier. Further, it showed that F3T3-positive cases overwhelmingly (in 96.7% of cases) fall into the mesenchymal or RTK II subclasses, which overlap in their methylation profiles, rather than the RTK I (or any other) subclass. In contrast, GBMs with EGFR or PDGFRA amplifications were assigned the RTK I subclass in 14.3% and 50.0% of cases, respectively, consistent with prior reports [10]. While it is unclear if the role of TACC3 in regulating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition may relate to the methylation characteristics of F3T3-positive GBM [24], it has been suggested that methylation subclass is reflective of tumor cell of origin as well as somatic epigenetic changes [11, 19, 25]. Our data show that while F3T3-positive GBMs are closely related to other IDH-wildtype GBMs, there are differences among these tumors that may be biologically significant.

The present study is among the first to provide long-term clinical follow-up data on a large cohort of patients with F3T3-positive tumors, with a median follow-up time of 55.6 months. Patients with F3T3-positive tumors were slightly older at initial diagnosis (63.6 vs. 59.4 years). Although older age at diagnosis is a well-established risk factor for poorer outcome and shorter overall survival in patients with GBM, patients with F3T3-positive GBMs in this study lived slightly longer than those without F3T3 fusions (26.7 vs. 18.5 months, p = 0.07), a difference that persisted after adjustment for potential confounders including age, sex, race, and MGMT status. Although this difference did not meet formal statistical significance, at the very least, we can conclude that patients with F3T3-positive tumors have clinical features and outcomes similar to, or perhaps slightly better than, those with non-F3T3-driven, IDH-wildtype GBMs.

Of note, F3T3 fusions have also been identified in lower-grade histologic entities [17, 23, 27, 29, 43]. Sufficient long-term follow up is lacking to determine if any among these are under-sampled higher-grade gliomas, or gliomas that eventually recur, progress, or otherwise behave aggressively. Furthermore, both low- and high-grade F3T3-positive gliomas exhibit characteristic histologic features, including monomorphous oligodendroglioma-like nuclei, “chicken-wire” capillary networks, and frequent microcalcifications [7]. While these features suggest the attractive hypothesis that F3T3-positive GBMs arise from lower-grade precursor lesions, to date there has been insufficient evidence to support this idea. Rather, our study underscores that F3T3 fusions, when detected in histologic GBM, drive clinical behavior akin to other IDH-wildtype GBMs.

Importantly, given the difference in overall survival suggested by this study, our findings raise the possibility that the underlying biology of F3T3-positive GBM may be a confounding factor in interpreting outcome data in the setting of pan-GBM clinical trials. Considering ongoing research into therapeutic inhibition of tyrosine kinase signaling in general and FGFR3 signaling specifically, identification of F3T3 fusions in patients with IDH-wildtype GBMs could soon have therapeutic implications. For example, the recent phase 2 REGOMA trial showed that median overall survival was approximately 2 months longer in patients with first recurrence of GBM after surgery and radiotherapy/TMZ receiving the oral multikinase inhibitor regorafenib rather than lomustine (7.4 vs. 5.6 months, p < 0.001) [30]. Notably, that study did not enroll patients based on a molecular alteration, nor did it report results stratified by underlying somatic genetic alterations, so its relevance to patients with F3T3-positive GBMs is uncertain.

FGFR signaling has been implicated in a variety of human cancers. FGFR pathway inhibition as a therapeutic strategy remains an area of active investigation, including in ongoing and recently completed clinical trials of FGFR inhibitors in brain tumors (e.g., NCT01975701, NCT028224133, NCT02052778, and NCT01948297). Other inhibitors of FGFR3 and F3T3 have also been tested in preclinical models and in trials in other tumor types, especially urothelial carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, for which therapeutics such as erdafitinib, rogaratinib, infigratinib, and the monoclonal antibody vofatamab have shown promise [12]. Recent research has also demonstrated that F3T3-positive tumors are characterized by mitochondrial activation, and that these tumors may be particularly susceptible to inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration and oxidative metabolism, highlighting this pathway as another potential therapeutic opportunity [20]. Aside from FGFR3, there is also interest in inhibiting TACC3, including with the potent new TACC3-targeting agent BO-264, which significantly inhibited the growth of cells harboring F3T3 fusions in a preclinical model [1].

This study has limitations. Although 906 cases were sequenced, only 137 underwent methylation array analysis. Also, an insufficient number of F3T3-positive patients in this cohort received F3T3-specific targeted therapy to evaluate the potential efficacy of such an approach, the determination of which awaits future clinical trials. Last, detailed treatment information was not available for all F3T3-wildtype patients, thus chemoradiotherapy treatment status was not adjusted for in the Cox proportional hazards regression models.

In conclusion, approximately 4% of IDH-wildtype GBMs in this study harbored potentially targetable F3T3 fusions. While their clinical and molecular characteristics were largely in keeping with other IDH-wildtype GBMs, they demonstrated characteristic associated mutational, copy-number, and methylation profiles, and patients with F3T3-positive tumors had clinical outcomes slightly better than patients with F3T3-wildtype tumors. F3T3-positivity was predominantly mutually exclusive with other RTK drivers, and F3T3-wildtype tumors were enriched for mutations in TP53. As histologic features lack specificity for identifying F3T3-positive tumors, comprehensive NGS and methylation analysis should be considered for all IDH-wildtype GBMs to identify patients for potential clinical trial enrollment and targeted treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Akbulut O, Lengerli D, Saatci O, Duman E, Seker UOS, Isik A, Akyol A, Caliskan B, Banoglu E, Şahin Ö (2020) A highly potent TACC3 inhibitor as a novel anti-cancer drug candidate. Mol Cancer Ther. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0957

Asif S, Fatima R, Krc R, Bennett J, Raza S (2019) Comparative proteogenomic characterization of glioblastoma. CNS Oncol 8:1–13. https://doi.org/10.2217/cns-2019-0003

Bady P, Sciuscio D, Diserens A-C, Bloch J, van den Bent MJ, Marosi C, Dietrich P-Y, Weller M, Mariani L, Heppner FL, Mcdonald DR, Lacombe D, Stupp R, Delorenzi M, Hegi ME (2012) MGMT methylation analysis of glioblastoma on the Infinium methylation BeadChip identifies two distinct CpG regions associated with gene silencing and outcome, yielding a prediction model for comparisons across datasets, tumor grades, and CIMP-status. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 124:547–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-012-1016-2

Bahceci I, Dogrusoz U, La KC, Babur Ö, Gao J, Schultz N (2017) PathwayMapper: a collaborative visual web editor for cancer pathways and genomic data. Bioinforma Oxf Engl 33:2238–2240. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx149

Bao Z-S, Chen H-M, Yang M-Y, Zhang C-B, Yu K, Ye W-L, Hu B-Q, Yan W, Zhang W, Akers J, Ramakrishnan V, Li J, Carter B, Liu Y-W, Hu H-M, Wang Z, Li M-Y, Yao K, Qiu X-G, Kang C-S, You Y-P, Fan X-L, Song WS, Li R-Q, Su X-D, Chen CC, Jiang T (2014) RNA-seq of 272 gliomas revealed a novel, recurrent PTPRZ1-MET fusion transcript in secondary glioblastomas. Genome Res 24:1765–1773. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.165126.113

Benhamida JK, Hechtman JF, Nafa K, Villafania L, Sadowska J, Wang J, Wong D, Zehir A, Zhang L, Bale T, Arcila ME, Ladanyi M (2020) Reliable clinical MLH1 promoter hypermethylation assessment using a high-throughput genome-wide methylation array platform. J Mol Diagn JMD 22:368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.11.005

Bielle F, Di Stefano A-L, Meyronet D, Picca A, Villa C, Bernier M, Schmitt Y, Giry M, Rousseau A, Figarella-Branger D, Maurage C-A, Uro-Coste E, Lasorella A, Iavarone A, Sanson M, Mokhtari K (2018) Diffuse gliomas with FGFR3-TACC3 fusion have characteristic histopathological and molecular features. Brain Pathol Zurich Switz 28:674–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12563

Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, Zheng S, Chakravarty D, Sanborn JZ, Berman SH, Beroukhim R, Bernard B, Wu C-J, Genovese G, Shmulevich I, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Zou L, Vegesna R, Shukla SA, Ciriello G, Yung WK, Zhang W, Sougnez C, Mikkelsen T, Aldape K, Bigner DD, Van Meir EG, Prados M, Sloan A, Black KL, Eschbacher J, Finocchiaro G, Friedman W, Andrews DW, Guha A, Iacocca M, O’Neill BP, Foltz G, Myers J, Weisenberger DJ, Penny R, Kucherlapati R, Perou CM, Hayes DN, Gibbs R, Marra M, Mills GB, Lander E, Spellman P, Wilson R, Sander C, Weinstein J, Meyerson M, Gabriel S, Laird PW, Haussler D, Getz G, Chin L, TCGA Research Network (2013) The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155:462–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2008) Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455:1061–1068. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07385

Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V, Schrimpf D, Sturm D, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Chavez L, Reuss DE, Kratz A, Wefers AK, Huang K, Pajtler KW, Schweizer L, Stichel D, Olar A, Engel NW, Lindenberg K, Harter PN, Braczynski AK, Plate KH, Dohmen H, Garvalov BK, Coras R, Hölsken A, Hewer E, Bewerunge-Hudler M, Schick M, Fischer R, Beschorner R, Schittenhelm J, Staszewski O, Wani K, Varlet P, Pages M, Temming P, Lohmann D, Selt F, Witt H, Milde T, Witt O, Aronica E, Giangaspero F, Rushing E, Scheurlen W, Geisenberger C, Rodriguez FJ, Becker A, Preusser M, Haberler C, Bjerkvig R, Cryan J, Farrell M, Deckert M, Hench J, Frank S, Serrano J, Kannan K, Tsirigos A, Brück W, Hofer S, Brehmer S, Seiz-Rosenhagen M, Hänggi D, Hans V, Rozsnoki S, Hansford JR, Kohlhof P, Kristensen BW, Lechner M, Lopes B, Mawrin C, Ketter R, Kulozik A, Khatib Z, Heppner F, Koch A, Jouvet A, Keohane C, Mühleisen H, Mueller W, Pohl U, Prinz M, Benner A, Zapatka M, Gottardo NG, Driever PH, Kramm CM, Müller HL, Rutkowski S, von Hoff K, Frühwald MC, Gnekow A, Fleischhack G, Tippelt S, Calaminus G, Monoranu C-M, Perry A, Jones C, Jacques TS, Radlwimmer B, Gessi M, Pietsch T, Schramm J, Schackert G, Westphal M, Reifenberger G, Wesseling P, Weller M, Collins VP, Blümcke I, Bendszus M, Debus J, Huang A, Jabado N, Northcott PA, Paulus W, Gajjar A, Robinson GW, Taylor MD, Jaunmuktane Z, Ryzhova M, Platten M, Unterberg A, Wick W, Karajannis MA, Mittelbronn M, Acker T, Hartmann C, Aldape K, Schüller U, Buslei R, Lichter P, Kool M, Herold-Mende C, Ellison DW, Hasselblatt M, Snuderl M, Brandner S, Korshunov A, von Deimling A, Pfister SM (2018) DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 555:469–474. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature26000

Capper D, Stichel D, Sahm F, Jones DTW, Schrimpf D, Sill M, Schmid S, Hovestadt V, Reuss DE, Koelsche C, Reinhardt A, Wefers AK, Huang K, Sievers P, Ebrahimi A, Schöler A, Teichmann D, Koch A, Hänggi D, Unterberg A, Platten M, Wick W, Witt O, Milde T, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, von Deimling A (2018) Practical implementation of DNA methylation and copy-number-based CNS tumor diagnostics: the Heidelberg experience. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 136:181–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1879-y

Casadei C, Dizman N, Schepisi G, Cursano MC, Basso U, Santini D, Pal SK, De Giorgi U (2019) Targeted therapies for advanced bladder cancer: new strategies with FGFR inhibitors. Ther Adv Med Oncol 11:1758835919890285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835919890285

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N (2012) The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2:401–404. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095

Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, Kundra R, Zhang H, Wang J, Rudolph JE, Yaeger R, Soumerai T, Nissan MH, Chang MT, Chandarlapaty S, Traina TA, Paik PK, Ho AL, Hantash FM, Grupe A, Baxi SS, Callahan MK, Snyder A, Chi P, Danila D, Gounder M, Harding JJ, Hellmann MD, Iyer G, Janjigian Y, Kaley T, Levine DA, Lowery M, Omuro A, Postow MA, Rathkopf D, Shoushtari AN, Shukla N, Voss M, Paraiso E, Zehir A, Berger MF, Taylor BS, Saltz LB, Riely GJ, Ladanyi M, Hyman DM, Baselga J, Sabbatini P, Solit DB, Schultz N (2017) OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00011

Chang MT, Asthana S, Gao SP, Lee BH, Chapman JS, Kandoth C, Gao J, Socci ND, Solit DB, Olshen AB, Schultz N, Taylor BS (2016) Identifying recurrent mutations in cancer reveals widespread lineage diversity and mutational specificity. Nat Biotechnol 34:155–163. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3391

Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, Chandramohan R, Liu ZY, Won HH, Scott SN, Brannon AR, O’Reilly C, Sadowska J, Casanova J, Yannes A, Hechtman JF, Yao J, Song W, Ross DS, Oultache A, Dogan S, Borsu L, Hameed M, Nafa K, Arcila ME, Ladanyi M, Berger MF (2015) Memorial sloan kettering-integrated mutation profiling of actionable cancer targets (MSK-IMPACT): a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn JMD 17:251–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006

Di Stefano AL, Fucci A, Frattini V, Labussiere M, Mokhtari K, Zoppoli P, Marie Y, Bruno A, Boisselier B, Giry M, Savatovsky J, Touat M, Belaid H, Kamoun A, Idbaih A, Houillier C, Luo FR, Soria J-C, Tabernero J, Eoli M, Paterra R, Yip S, Petrecca K, Chan JA, Finocchiaro G, Lasorella A, Sanson M, Iavarone A (2015) Detection, characterization, and inhibition of FGFR-TACC fusions in IDH wild-type Glioma. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 21:3307–3317. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2199

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative STROBE (2007) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet Lond Engl 370:1453–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X

Fernandez AF, Assenov Y, Martin-Subero JI, Balint B, Siebert R, Taniguchi H, Yamamoto H, Hidalgo M, Tan A-C, Galm O, Ferrer I, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Villanueva A, Carmona J, Sanchez-Mut JV, Berdasco M, Moreno V, Capella G, Monk D, Ballestar E, Ropero S, Martinez R, Sanchez-Carbayo M, Prosper F, Agirre X, Fraga MF, Graña O, Perez-Jurado L, Mora J, Puig S, Prat J, Badimon L, Puca AA, Meltzer SJ, Lengauer T, Bridgewater J, Bock C, Esteller M (2012) A DNA methylation fingerprint of 1628 human samples. Genome Res 22:407–419. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.119867.110

Frattini V, Pagnotta SM, Tala null Fan JJ, Russo MV, Lee SB, Garofano L, Zhang J, Shi P, Lewis G, Sanson H, Frederick V, Castano AM, Cerulo L, Rolland DCM, Mall R, Mokhtari K, Elenitoba-Johnson KSJ, Sanson M, Huang X, Ceccarelli M, Lasorella A, Iavarone A (2018) A metabolic function of FGFR3-TACC3 gene fusions in cancer. Nature 553:222–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25171

Frattini V, Trifonov V, Chan JM, Castano A, Lia M, Abate F, Keir ST, Ji AX, Zoppoli P, Niola F, Danussi C, Dolgalev I, Porrati P, Pellegatta S, Heguy A, Gupta G, Pisapia DJ, Canoll P, Bruce JN, McLendon RE, Yan H, Aldape K, Finocchiaro G, Mikkelsen T, Privé GG, Bigner DD, Lasorella A, Rabadan R, Iavarone A (2013) The integrated landscape of driver genomic alterations in glioblastoma. Nat Genet 45:1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2734

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N (2013) Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.2004088

Granberg KJ, Annala M, Lehtinen B, Kesseli J, Haapasalo J, Ruusuvuori P, Yli-Harja O, Visakorpi T, Haapasalo H, Nykter M, Zhang W (2017) Strong FGFR3 staining is a marker for FGFR3 fusions in diffuse gliomas. Neuro-Oncol 19:1206–1216. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox028

Ha G-H, Park J-S, Breuer E-KY (2013) TACC3 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through the activation of PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling pathways. Cancer Lett 332:63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.013

Hovestadt V, Jones DTW, Picelli S, Wang W, Kool M, Northcott PA, Sultan M, Stachurski K, Ryzhova M, Warnatz H-J, Ralser M, Brun S, Bunt J, Jäger N, Kleinheinz K, Erkek S, Weber UD, Bartholomae CC, von Kalle C, Lawerenz C, Eils J, Koster J, Versteeg R, Milde T, Witt O, Schmidt S, Wolf S, Pietsch T, Rutkowski S, Scheurlen W, Taylor MD, Brors B, Felsberg J, Reifenberger G, Borkhardt A, Lehrach H, Wechsler-Reya RJ, Eils R, Yaspo M-L, Landgraf P, Korshunov A, Zapatka M, Radlwimmer B, Pfister SM, Lichter P (2014) Decoding the regulatory landscape of medulloblastoma using DNA methylation sequencing. Nature 510:537–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13268

Hovestadt V, Zapatka M (2017) conumee: Enhanced copy-number variation analysis using Illumina DNA methylation arrays. Division of Molecular Genetics, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg

Huse JT, Snuderl M, Jones DTW, Brathwaite CD, Altman N, Lavi E, Saffery R, Sexton-Oates A, Blumcke I, Capper D, Karajannis MA, Benayed R, Chavez L, Thomas C, Serrano J, Borsu L, Ladanyi M, Rosenblum MK (2017) Polymorphous low-grade neuroepithelial tumor of the young (PLNTY): an epileptogenic neoplasm with oligodendroglioma-like components, aberrant CD34 expression, and genetic alterations involving the MAP kinase pathway. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 133:417–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1639-9

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2016) WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system, revised, 4th edn. World Health Organization, Lyon

Johnson A, Severson E, Gay L, Vergilio J-A, Elvin J, Suh J, Daniel S, Covert M, Frampton GM, Hsu S, Lesser GJ, Stogner-Underwood K, Mott RT, Rush SZ, Stanke JJ, Dahiya S, Sun J, Reddy P, Chalmers ZR, Erlich R, Chudnovsky Y, Fabrizio D, Schrock AB, Ali S, Miller V, Stephens PJ, Ross J, Crawford JR, Ramkissoon SH (2017) Comprehensive genomic profiling of 282 pediatric low- and high-grade gliomas reveals genomic drivers, tumor mutational burden, and hypermutation signatures. Oncologist 22:1478–1490. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0242

Lombardi G, De Salvo GL, Brandes AA, Eoli M, Rudà R, Faedi M, Lolli I, Pace A, Daniele B, Pasqualetti F, Rizzato S, Bellu L, Pambuku A, Farina M, Magni G, Indraccolo S, Gardiman MP, Soffietti R, Zagonel V (2019) Regorafenib compared with lomustine in patients with relapsed glioblastoma (REGOMA): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30675-2

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Angelantonio ED, Sen S (2015) Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 314:2373–2383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

Mikeska T, Bock C, El-Maarri O, Hübner A, Ehrentraut D, Schramm J, Felsberg J, Kahl P, Büttner R, Pietsch T, Waha A (2007) Optimization of quantitative MGMT promoter methylation analysis using pyrosequencing and combined bisulfite restriction analysis. J Mol Diagn JMD 9:368–381. https://doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060167

Na K, Kim H-S, Shim HS, Chang JH, Kang S-G, Kim SH (2019) Targeted next-generation sequencing panel (TruSight Tumor 170) in diffuse glioma: a single institutional experience of 135 cases. J Neurooncol 142:445–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03114-1

Parker BC, Annala MJ, Cogdell DE, Granberg KJ, Sun Y, Ji P, Li X, Gumin J, Zheng H, Hu L, Yli-Harja O, Haapasalo H, Visakorpi T, Liu X, Liu C-G, Sawaya R, Fuller GN, Chen K, Lang FF, Nykter M, Zhang W (2013) The tumorigenic FGFR3-TACC3 gene fusion escapes miR-99a regulation in glioblastoma. J Clin Invest 123:855–865. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI67144

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA (2016) Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316:2214–2236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17324

Sarkar S, Ryan EL, Royle SJ (2017) FGFR3-TACC3 cancer gene fusions cause mitotic defects by removal of endogenous TACC3 from the mitotic spindle. Open Biol. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.170080

Shen R, Seshan VE (2016) FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 44:e131. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw520

Singh D, Chan JM, Zoppoli P, Niola F, Sullivan R, Castano A, Liu EM, Reichel J, Porrati P, Pellegatta S, Qiu K, Gao Z, Ceccarelli M, Riccardi R, Brat DJ, Guha A, Aldape K, Golfinos JG, Zagzag D, Mikkelsen T, Finocchiaro G, Lasorella A, Rabadan R, Iavarone A (2012) Transforming fusions of FGFR and TACC genes in human glioblastoma. Science 337:1231–1235. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1220834

Snuderl M, Fazlollahi L, Le LP, Nitta M, Zhelyazkova BH, Davidson CJ, Akhavanfard S, Cahill DP, Aldape KD, Betensky RA, Louis DN, Iafrate AJ (2011) Mosaic amplification of multiple receptor tyrosine kinase genes in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 20:810–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.005

Szerlip NJ, Pedraza A, Chakravarty D, Azim M, McGuire J, Fang Y, Ozawa T, Holland EC, Huse JT, Jhanwar S, Leversha MA, Mikkelsen T, Brennan CW (2012) Intratumoral heterogeneity of receptor tyrosine kinases EGFR and PDGFRA amplification in glioblastoma defines subpopulations with distinct growth factor response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:3041–3046. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114033109

Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, Srinivasan P, Gao J, Chakravarty D, Devlin SM, Hellmann MD, Barron DA, Schram AM, Hameed M, Dogan S, Ross DS, Hechtman JF, DeLair DF, Yao J, Mandelker DL, Cheng DT, Chandramohan R, Mohanty AS, Ptashkin RN, Jayakumaran G, Prasad M, Syed MH, Rema AB, Liu ZY, Nafa K, Borsu L, Sadowska J, Casanova J, Bacares R, Kiecka IJ, Razumova A, Son JB, Stewart L, Baldi T, Mullaney KA, Al-Ahmadie H, Vakiani E, Abeshouse AA, Penson AV, Jonsson P, Camacho N, Chang MT, Won HH, Gross BE, Kundra R, Heins ZJ, Chen H-W, Phillips S, Zhang H, Wang J, Ochoa A, Wills J, Eubank M, Thomas SB, Gardos SM, Reales DN, Galle J, Durany R, Cambria R, Abida W, Cercek A, Feldman DR, Gounder MM, Hakimi AA, Harding JJ, Iyer G, Janjigian YY, Jordan EJ, Kelly CM, Lowery MA, Morris LGT, Omuro AM, Raj N, Razavi P, Shoushtari AN, Shukla N, Soumerai TE, Varghese AM, Yaeger R, Coleman J, Bochner B, Riely GJ, Saltz LB, Scher HI, Sabbatini PJ, Robson ME, Klimstra DS, Taylor BS, Baselga J, Schultz N, Hyman DM, Arcila ME, Solit DB, Ladanyi M, Berger MF (2017) Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med 23:703–713. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4333

Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B, Orisme W, Punchihewa C, Parker M, Qaddoumi I, Boop FA, Lu C, Kandoth C, Ding L, Lee R, Huether R, Chen X, Hedlund E, Nagahawatte P, Rusch M, Boggs K, Cheng J, Becksfort J, Ma J, Song G, Li Y, Wei L, Wang J, Shurtleff S, Easton J, Zhao D, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Dooling DJ, Vadodaria B, Mulder HL, Tang C, Ochoa K, Mullighan CG, Gajjar A, Kriwacki R, Sheer D, Gilbertson RJ, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Downing JR, Baker SJ, Ellison DW, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital–Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project (2013) Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet 45:602–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2611

Zhou X, Edmonson MN, Wilkinson MR, Patel A, Wu G, Liu Y, Li Y, Zhang Z, Rusch MC, Parker M, Becksfort J, Downing JR, Zhang J (2016) Exploring genomic alteration in pediatric cancer using ProteinPaint. Nat Genet 48:4–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3466

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the members of the Molecular Diagnostics Service in the Department of Pathology at MSK and Andreas Von Deimling from the University of Heidelberg.

Funding

This work has been supported in part by the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology and the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant No. P30-CA008748.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: DAM, JKB, and TAB. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: DAM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: DAM and JKB. Supervision: JKB, ALL, AMM, MKR, ML, TAB.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the MSK Institutional Review Board. Patients provided informed consent for paired tumor-normal DNA and methylation array analysis at the point of care.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

A.L. Lin reports receiving commercial research grants from NantOmics and Bristol-Myers Squibb. V. Tabar and/or her immediate family members report receiving commercial research grants from and serving as consultant/advisory board members for BlueRock Therapeutics. N. Moss has consulted for AstraZeneca. I.K. Mellinghoff reports receiving commercial research grants from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and General Electric and is a consultant/advisory board member for Agios Pharmaceuticals, Black Diamond Therapeutics, DC Europa Ltd., Debiopharm Group, Puma Biotechnology, and Voyager Therapeutics. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1

. Online supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mata, D.A., Benhamida, J.K., Lin, A.L. et al. Genetic and epigenetic landscape of IDH-wildtype glioblastomas with FGFR3-TACC3 fusions. acta neuropathol commun 8, 186 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-01058-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-01058-6