Abstract

The family of juvenile xanthogranuloma family neoplasms (JXG) with ERK-pathway mutations are now classified within the “L” (Langerhans) group, which includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and Erdheim Chester disease (ECD). Although the BRAF V600E mutation constitutes the majority of molecular alterations in ECD and LCH, only three reported JXG neoplasms, all in male pediatric patients with localized central nervous system (CNS) involvement, are known to harbor the BRAF mutation. This retrospective case series seeks to redefine the clinicopathologic spectrum of pediatric CNS-JXG family neoplasms in the post-BRAF era, with a revised diagnostic algorithm to include pediatric ECD. Twenty-two CNS-JXG family lesions were retrieved from consult files with 64% (n = 14) having informative BRAF V600E mutational testing (molecular and/or VE1 immunohistochemistry). Of these, 71% (n = 10) were pediatric cases (≤18 years) and half (n = 5) harbored the BRAF V600E mutation. As compared to the BRAF wild-type cohort (WT), the BRAF V600E cohort had a similar mean age at diagnosis [BRAF V600E: 7 years (3–12 y), vs. WT: 7.6 years (1–18 y)] but demonstrated a stronger male/female ratio (BRAF V600E: 4 vs WT: 0.67), and had both more multifocal CNS disease ( BRAFV600E: 80% vs WT: 20%) and systemic disease (BRAF V600E: 40% vs WT: none). Radiographic features of CNS-JXG varied but typically included enhancing CNS mass lesion(s) with associated white matter changes in a subset of BRAF V600E neoplasms. After clinical-radiographic correlation, pediatric ECD was diagnosed in the BRAF V600E cohort. Treatment options varied, including surgical resection, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy with BRAF-inhibitor dabrafenib in one mutated case. BRAF V600E CNS-JXG neoplasms appear associated with male gender and aggressive disease presentation including pediatric ECD. We propose a revised diagnostic algorithm for CNS-JXG that includes an initial morphologic diagnosis with a final integrated diagnosis after clinical-radiographic and molecular correlation, in order to identify cases of pediatric ECD. Future studies with long-term follow-up are required to determine if pediatric BRAF V600E positive CNS-JXG neoplasms are a distinct entity in the L-group histiocytosis category or represent an expanded pediatric spectrum of ECD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the most recent revised classification of histiocytic disorders, [21], cutaneous juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) lesions and those JXG lesions with a systemic component, but not associated with a molecular alteration, are categorized separately into the cutaneous or “C”-group histiocytosis. However, extracutaneous JXG lesions with mitogen activated pathway kinase (MAPK) / extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway activating mutations are now categorized into the Langerhans “L-group” histiocytosis, including three rare BRAF V600E JXG “L-group” neoplasm [56]. In this revised classification, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and Erdheim Chester Disease (ECD), are also categorized in the “L group” of histiocytic neoplasms. At the far ends of their phenotypic spectra, LCH, ECD, and JXG all have distinct clinical and pathologic features; however, this shared categorization was proposed based on similar molecular alterations, mixed LCH/ECD histiocytic presentations in adult cases, and accumulating data supporting a common hematopoietic precursor, at least between adult LCH and ECD [21]. However, pediatric extracutaneous JXG with MAPK molecular alterations as an L-group histiocytosis, has been less studied in relation to its possible shared origins with LCH and pediatric ECD [10, 16, 38, 40, 46, 51] Furthermore, while the BRAF V600E mutation constitutes the majority of molecular alterations in ECD and LCH [3, 5, 30, 53], only three reported JXG neoplasms, all in male pediatric patients with localized central nervous system (CNS) involvement, are known to harbor the BRAF mutation; however, none showed evidence of systemic disease or a prior history of LCH [56].

In general, CNS-JXG neoplasm are rare, often requiring surgical resection or chemotherapy [13, 36, 55, 58] and do not have the propensity to regress spontaneously, unlike their cutaneous JXG counterpart [58]. CNS-JXG neoplasm range from isolated CNS lesions to multifocal CNS lesions to those associated with systemic disease [6, 13, 22, 26, 27, 36, 58]. In adults, CNS based neoplasms with a JXG or xanthogranuloma pathologic phenotype are often the first and most debilitating manifestation of ECD. They are often a challenge to diagnose and have a generally poor prognosis; however, in adults these neoplasms often have an excellent response to inhibitor therapy [15, 24, 48]. In children, both systemic JXG with CNS involvement and CNS-limited JXG also appear to have poorer outcomes, as compared to pediatric JXG without CNS disease; however, none of these prior pediatric JXG studies have investigated the BRAF mutational status [13, 58].

Furthermore, the current revised classification of histiocytes [21] has created a divide between the JXG family of neoplasms with molecular alterations (L-group) and those without molecular alterations (C-group). Standing alone, this grouping does not have particular clinical significance, especially given that both C-group and even R-group histiocytic lesions now also harbor MAPK-pathway activated mutations [16, 25, 28, 44, 49, 52]. Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that CNS neoplasms have an initial morphologic report followed by an integrated final diagnosis after molecular studies are completed [42]. The aim of this study is to revisit the pathology and incidence of BRAF V600E mutations in pediatric CNS-JXG neoplasms in order to propose a revised diagnostic algorithm that requires the integration of pathology, molecular, clinical, and radiographic findings for a comprehensive final diagnosis, in the hope of advancing clinical management and treatment options.

Materials and methods

Cases: inclusion and exclusion criteria

Following institutional review board approval (University of Pittsburgh IRB number PRO12110055), we retrieved cases from our pathology consult files for CNS-based JXG family lesions, which includes previously published pediatric cases [14, 55, 57]. In our initial inclusion criteria, we included all cases that were diagnosed as a JXG family neoplasm by morphology and immunophenotype, as previously described [8, 50, 59]. In brief, JXG family neoplasms range from 1) small to intermediate-sized mononuclear histiocytes, to 2) abundant foamy, xanthomatous (i.e. lipidized) histiocytes and Touton giant cells, to 3) those lesions resembling benign fibrous histiocytoma with a predominance of spindle-shaped cells and fibrosis with lesser quantity of foamy histiocytes and giant cells, while also including 4) oncocytic cells with abundant glassy pink cytoplasm (i.e reticulohistiocytoma” subtype). Under the microscope JXG and ECD share similar morphologic patterns and a shared immunophenotype (i.e., positive: CD163, CD68, CD14, Factor 13a, fascin, typically S100 negative, and CD1a and Langerin negative). Both JXG and ECD can be diagnosed as “JXG family” on pathologic grounds alone, with the distinction of ECD made by correlating appropriate clinical and radiographic features, as previously described [15].

Case files were reviewed over a 20-year time span (1998–2018). Detailed clinical, radiographic, and therapy-related data were collected for all available patients. Exclusion criteria comprised those CNS-JXG cases with a mixed histiocytic phenotype (n = 6), including LCH either concurrently or previous to the CNS-JXG diagnosis; CNS histiocytic sarcoma with JXG immunophenotype (n = 3), and CNS-JXG following leukemia (n = 2) (Fig. 1), as these lesions carry different biologic potentials.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 3 μm thick formalin fixed paraffin embed (FFPE) sections using commercially available antibodies: CD163, CD68 PGM1, CD14, Factor XIIIa, Fascin, Ki-67, S100, CD1a, Langerin, and Braf-VE1 (Table 1).

BRAF V600E assessment

BRAF status was assessed either by DNA-based studies and/or immunohistochemistry with a clinically validated BRAF V600E (VE1) immunohistochemical stain (Table 1). Previous in-house validation and others have shown a very high correlation with molecular status when diffuse 2–3+ intensity granular staining is present in > 10% of while negative cases had either complete absence of staining, weak/faint granular staining (1+) or staining in only rare, single scattered cells, often not possessing the morphology of a histiocytic cell [41]. For those that had molecular testing around the time of diagnosis, a variety of methodologies were used, dependent on the referring institution. A single sample (case 3) underwent PCR Sanger Sequence locally at our institution on available FFPE consult block material of the CNS-JXG lesion, along with Braf-VE1 immunostaining. Briefly, a manual microdissection was performed on this sample (> 50% tumor cells present). DNA was isolated using standard laboratory procedure with optical density readings. For the detection of the mutation, Light Cycler Platform (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. Pleasanton, California) was used to amplify BRAF exon 15 codons 599–601 sequences. Post-PCR melt curve analysis was used to detect mutation and confirmed with Sanger Sequencing of the PCR product on ABI3130 (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). The limit of detection was approximately 10–20% of alleles with mutation present in background of normal DNA.

Results

We identified 22 CNS lesions with JXG phenotype that met our initial inclusion criteria (Fig. 1), designated as CNS-JXG. Fourteen CNS-JXG cases (64%) had informative molecular status for the BRAF V600E point mutation, which included 10 pediatric CNS-JXG neoplasms that were included in the primary analysis. The overall mean age was 7.3 years (range: 1–18 y) with a male/female ratio of 1.5 (Table 2). Within such a small cohort it is difficult to ascertain clinically relevant, statistical difference between the pediatric BRAF V600E (n = 5) and BRAF wild-type (n = 5) CNS-JXG cohorts, but certain trends were noted. There was a similar mean age in both cohorts [BRAF V600E: 7 years (3–12 y) vs BRAF wild-type 7.6 years (1–18 years)]. While the overall male/female ratio in the pediatric CNS-JXG cohort was male predominant (1.5), the BRAF V600E cohort had more males (male/female ratio: 4.0), as compared to the wild type cohort (male/female ratio: 0.67). The pediatric BRAF V600E cohort also had more cases of multifocal CNS disease [BRAF V600E: 3/5 (60%) vs the BRAF wild-type: 1/5 (20%)] along with associated CNS white matter changes and enhancement of nodular lesions (Table 2). The two cases with systemic disease were BRAF V600E positive (Table 2). One had multifocal CNS-JXG disease, including intracranial, sellar, dural, ventricular, and cavernous sinus involvement, along with bilateral long bone sclerosis and confirmatory bone biopsy also with the BRAF V600E mutation (case 3). Thus the integrated final diagnosis with pathology and radiographic correlation was that of pediatric ECD, as previously published [14]. The second case also had systemic disease, with an associated cutaneous BRAF V600E positive JXG lesions. Symmetric CNS white matter changes were present on MRI (Fig. 2i-l), along with an enhancing parenchymal mass; however, there was no evidence of bone involvement or other classic features of ECD. One of the BRAF V600E cases with multifocal CNS lesions had visual decline and panhypopituitarism from sellar/optic chiasm-based masses, while the other had resultant encephalomalacia and brain atrophy with progressive developmental delay and was started on hospice care six years after initial presentation (Table 2). In contrast, the BRAF wild-type cohort had more isolated CNS lesions without mention of associated symmetric white matter changes or reported systemic disease; however, one of these cases did not have long term follow-up after diagnosis (Table 2). The BRAF wild type group also did not have further molecular testing or phosphorylated-ERK staining.

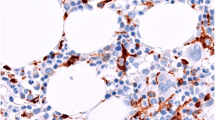

Morphologic, BRAF-VE1 expression, and CNS radiographic features of BRAF V600E CNS-JXG neoplasm. Various histiologic patterns in one lesion including: a Epithelioid histiocytes (h&e) with b strong (3+) diffuse BRAF-VE1 staining of histiocytes c Plump, pale histiocyes with d moderate (2+) diffuse BRAF-VE1 staining including some foamy histiocytes. e More abundant foamy/xanthomatous histiocytes with f variable moderate (2+) to weak (1+) to focally BRAF-VE1 negative xanthomatous histiocytes, and g fibrohistiocytic areas with only weak (1+) BRAF-VE1 staining in focal histioyctes with others negative. Original magnifications at 400x. i-l. MRI imaging showing i T1 axial with contrast pre-biopsy with dominant focal enhancing lesion in the right frontal lobe (white arrow) and j status post-excisional biopsy. k T2 axial with extensive confluent, nearly symmetric white matter T2 hyper-intensity throughout the cerebral hemispheres, with a posterior predominance, and a mottled appearance (black arrows) and dominant right frontal lobe lesion (white arrow), l status post excisional biopsy with a small amount of CSF fluid in the surgical bed and peripheral enhancement along the surgical tract (white arrow) with innumerable nodular mottled T2 hypo-intensities throughout a background of diffusely abnormal hyper-intense T2 white matter abnormalities in the bilateral cerebral hemispheres (black arrows)

Pathologic features of the pediatric BRAF informative cohort

The presence of the BRAF V600E mutation did not appear to confer a selective morphologic pattern (Table 3). Both cohorts displayed varied histologic features within the morphologic (Fig. 2) and immunophenotypic spectrum of JXG-family (Table 3). Nine of the pediatric cases had S100 available for evaluation. Two BRAF V600E cases and three wild-type cases had scattered S100 positive Rosai- Dorfman-Destombes Disease (RDD)-like cells, along with an additional case in wild-type cohort with multinucleated giant cells and rare cells with emperipolesis, despite no S100 expression (Table 3). Half of the pediatric cases had assessment by Ki-67/MIB-1 immunohistochemistry, with an overall low proliferation index (0–15%) when accounting for intermixed inflammatory cells. The two BRAF V600E cases had subjectively lower median proliferation rate (2%), as compared to the three pediatric wild-type cases (15%) (Table 3); however, there are too few cases to draw statistical conclusions on these results. Focal mild cellular pleomorphism was noted in both groups, but there was no evidence of frank anaplasia or diffuse atypia. Only one of the BRAF wild-type cases (case 6) had central ischemic type necrosis (Table 3). The BRAF-VE1 immunostain showed diffuse, strong (2–3+) granular cytoplasmic expression in the majority of the lesional histocytes (> 75%). However, there was variable staining expression noted in the different JXG-histiocyte subtypes, including within a single lesion. For example, diffuse strong (3+) VE1 expression was noted in epithelioid and finely vacuolated JXG cells, diffuse but moderate (2+) expression in foamy/xanthomatous JXG cells, and weak to negative staining (0–1+) in the fibrohistiocytic JXG component that had more heavily xanthomatous/lipidized cells intermixed with fibrosis/gliosis (Fig. 2). All wild-type cases had a mixture of cell types, with negative staining in the epithelioid/finely vacuolated and foamy/xanthomatous JXG cells (Table 3).

Therapy and outcomes of the pediatric BRAF informative cohort

Treatment options in pediatric CNS-JXG cases were variable showing a combination of both surgical excision and systemic chemotherapy (Table 2). For most BRAF V600E CNS-JXG cases, the BRAF mutational status was not known at the time of initial diagnosis. Treatments included the following: LCH III based protocol with prednisone/vinblastine for 12 months in unifocal CNS disease of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, clofarabine and dexamethasone for systemic JXG with multifocal CNS-JXG, anakinra for pediatric ECD that had previously progressed on prednisone/vinblastine for 6 weeks, cladribine for 6 cycles, and clofarabine for 2 cycles [14], and BRAF-inhibitor therapy with dabrafenib for a multifocal CNS disease, which was aggressive and refractory to first line therapy. In this last case, dabrafenib showed an immediate and dramatic clinical response, including complete resolution of hyperventilation and weaning from dexamethasone with interval MRI at 2 months, 4 months and 15 month of therapy, along with a reduction in intracranial size and no new lesions. (Table 2). Case 4 did not have a known BRAF V600E prospectively in his course with progressive CNS white matter disease in the years following excision. The wild-type cases also had surgical resection with initial prednisone/vinblastine and then cladribine in one case with multifocal lesions and prednisone/vinblastine in a unifocal lesion of the cerebellopontine angle of a 1-year-old (Table 2).

Discussion

This retrospective case series characterizes the largest series to date of BRAF V600E mutated pediatric JXG family neoplasms, all of which were first diagnosed with CNS disease and share a striking young male predominance with aggressive disease. As compared to the three previous reported BRAF mutated cases [56] and our BRAF-wild type case, there was a similar age distribution throughout, but overall more boys are represented in the BRAF V600E cohort. Radiographically, the majority of BRAF V600E CNS-JXG neoplasms had multifocal CNS disease, often with contrast enhancement and a subset were noted to have background white matter changes, suggestive of neurodegeneration, which is also a feature shared in cases of CNS-ECD and CNS-LCH [15, 45]. Two of our BRAF V600E CNS-JXG cases also presented with systemic disease, including one classic pediatric ECD with long bone involvement and one case with cutaneous JXG and associated CNS white matter disease. In both cases, the non-CNS systemic lesions also demonstrated the BRAF V600E mutation. Treatment options varied in this case series, but those with BRAF V600E may benefit from targeted inhibitor therapy, especially in aggressive or refractory disease and may halt progressive decline from histiocytosis-associated neurodegeneration, which is now recognized as a BRAF V600E driven progress [32, 43, 45]. Together with previous published cases [56], our findings support the classification of CNS-JXG neoplasms with BRAF V600E into the current “L group” histiocytic neoplasm category [21], with all CNS-JXG neoplasms benefiting from upfront molecular testing including MAPK/ERK pathway mutations and possibly also ALK fusions/mutations [12]. Thus for clinical-pathologic relevance in CNS lesions, we propose that the neuropathologist first focus on an accurate diagnosis of CNS-JXG neoplasm. Recognizing the varied histologic subtypes and shared immunophenotype with ECD is foremost. Following this, integration with molecular testing and clinical/radiographic staging will allow for a more comprehensive, integrated final diagnosis, similar to the current WHO process for other CNS neoplasms. Furthermore, recognizing malignant cytology [47] or a previous diagnosis of leukemia/lymphoma in the same patient [9], or an associated histiocytosis including LCH [38] (either concurrently with the CNS-JXG neoplasm or previously diagnosed in the same patient) is also imperative, as all three of these instances will have different and distinct outcomes. This study specifically excluded such cases, including mixed histiocytosis, which needs further investigation to understand whether BRAF V600E mixed pediatric CNS LCH-JXG lesions also share a common hematopoietic precursor, similar to adult BRAF V600E LCH-ECD histiocytosis [4, 34]. Thus, by encompassing a comprehensive diagnostic algorithm for CNS-JXG neoplasms with morphology, molecular, clinical, and radiographic correlation, the neuropathologist will enable a heightened awareness amongst the clinical team for appropriate management and treatment, including prevention of BRAF V600E driven neurodegeneration, similar to LCH [45].

The pediatric BRAF V600E CNS-JXG neoplasms in this series share histologic and variable clinical/radiographic overlap with adult ECD cases, including one classic pediatric ECD. The other BRAF mutant cases, including the systemic cutaneous case with CNS-white matter changes, are suggestion of pediatric ECD, despite no diagnostic long bone involvement or other classic radiographic ECD findings, as described in adults [15]. In fact, pediatric ECD may present differently than adults and often experience a delay in diagnosis from months to years, given the rare reporting in the literature [37,38,39]. Since there are so few pediatric examples, it may be difficult to know the full clinical-radiographic spectrum of pediatric ECD, which in part may be due to underreporting in the pre-BRAF era. While in an adult, a nodular parenchymal BRAF V600E CNS-JXG diagnosed neoplasm with background CNS white matter changes and a cutaneous BRAF mutated xanthogranuloma lesion is highly suggestive of ECD [23], in children this presentation is not as well recognized as a form of pediatric ECD, especially in the pre-BRAF era [7]. In children, isolated skin JXG lesion are not known to harbor the BRAF V600E mutation (i.e., grouped as “C group” lesions) [49, 56]; however, in adults a cutaneous BRAF V600E xanthogranuloma is highly correlative with ECD, especially xanthelasmas, and should immediately prompt further clinico-radiographic investigation for ECD after biopsy diagnosis [15]. Thus, we propose that the same should be true for pediatric CNS-JXG lesions in which a morphologic diagnosis is only the first step in diagnosis. While our CNS-JXG pediatric patient, with an associated BRAF V600E skin lesion did not have classic radiographic stigmata of ECD and has thus far responded to clofarabine and dexamethasone with clinical and radiographic improvement, the background radiographic features suggestive of ECD-related neurodegeneration should be further followed in this setting. Furthermore, two other BRAF V600E positive CNS-JXG cases in our series also had features suggestive of ECD with progressive multifocal CNS disease resulting in cognitive decline, including brain atrophy. Despite the lack of long bone sclerosis or other classic ‘adult-type’ ECD findings, our cases not only share similarities with the aggressive cognitive decline that are observed in adult ECD, but also share radiographic features including associated white matter changes and brain atrophy [15, 18, 23, 29, 45].

For these reasons, adult ECD cases with CNS involvement are generally associated with poor prognosis [2]. Similarly, in one of the largest studies of previously published CNS-JXG [58], there was a higher rate (18.6%) of mortality/morbidity in both the isolated CNS-JXG neoplasms and those associated with systemic disease, as compared to the low mortality/morbidity (1–2%) of JXG in general [13, 36]. However, none of these previous JXG studies or registries included molecular testing, which would likely help further stratify patients, given our emerging data. In fact, one aggressive multifocal BRAF V600E CNS-JXG in this series, originally diagnosed in the pre-BRAF era, had poor prognosis with a rapidly progressive CNS disease with transition to hospice care, while the other BRAF V600E case, diagnosed prospectively, benefited from initiation with upfront BRAF-inhibitor therapy and had a dramatic and quick clinical response.

This type of immediate and favorable response is similar to the BRAF- and MAPK-inhibitor therapy in both adult ECD and LCH patients [17, 19, 24, 31]. However, this study was not designed to assess what constitutes best treatment protocols. It rather only highlights the lack of standard treatment protocols among the various cases. Treatment for CNS-JXG lesions should first take into account the final integrated diagnosis based on accurate morphologic diagnosis with molecular correlation and clinical/radiographic staging. However, in order to draw meaningful conclusions and develop consensus guidelines, long-term systematic study of these rare patients with follow-up is needed. To this end the Histiocyte Society’s International Rare Histiocytic Disorders Registry (NCT02285582) and subsequent prospective studies are poised to help accomplish this endeavor.

In the post-BRAF era, we now turn our attention to the molecular classification of histiocytic neoplasms as an area of ongoing, active investigation, which now includes extracutaneous JXG with BRAF V600E and MAPK pathway mutations, in addition to LCH and ECD with BRAF V600E mutations, and even rare reports of RDD with BRAF V600E [25, 44]. Thus, the question of whether the L-group histiocytic group should include only LCH/ECD or whether a more inclusive category of “MAPK-pathway activated histiocytoses” should now exist for all groups will need further discussion. Nonetheless, histology remains a seminal discriminator, as many other CNS tumors carry the BRAF V600E mutation, including both primary CNS (i.e., pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma, pilocytic astrocytoma, papillary craniopharyngioma) and metastatic CNS tumors (i.e., melanoma, carcinomas including colorectal cancer). Thus, it is of foremost importance that the pathologist accurately diagnose these histiocytic neoplasms, with heightened awareness of their varied histopathologic patterns within the rubric of JXG family neoplasms, which may include ECD [8, 59, 60]. The radiologist must also be aware of their varied radiographic presentations as focal, multifocal, and possible association with white matter changes and brain atrophy, which can further progress years after surgical excision of the main enhancing parenchymal lesion. We advocate applying a consistent JXG-immunostain panel, including molecular based immunostains that will aid in the pathologic diagnosis of these neoplasms, given their variable morphologic features. It is also important to exclude other histiocytosis, including LCH both by morphology and CD1a/Langerin immunostains and RDD by morphology of large RDD histiocytes (with and without emperipolesis) with diffuse, dark S100/fascin immunostains [50]. At least one case in our series carried an erroneous diagnosis of RDD based on a subset of scattered S100 positive cells. Typically S100 immunostain has limited value in the CNS lesions with high background staining; however, a subset of CNS-JXG cases in this series had variable light nuclear and cytoplasmic S100 staining in the lesional histiocytes, with and without emperipolesis. This light staining pattern with S100 in a subset of JXG cells should be distinguished from CNS-RDD, which has strong/diffuse S100 and fascin staining of lesional histiocytes and lacks Factor XIIIa staining. Scattered RDD-like cells with emperipolesis and variable light S100 staining has been previously noted in cutaneous JXG-family lesions [33, 54]. Furthermore BRAF V600E mutations have also been identified in rare cases of RDD [25, 44], including a variant BRAF mutation with CNS disease [52], which further emphasizes that morphology combined with molecular are useful for accurate diagnosis.

A significant limitation of our study is the retrospective nature of this case series with limited follow-up and inability to test the BRAF-wild type cohort for additional MAPK pathway mutations. An immunohistochemical stain for phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) is commercially available which can provide additional evidence for upregulation of the MAPK pathway as evidenced by diffuse expression in the majority of histiocytes [11, 35]. Unfortunately, many cases had no additional material to perform pERK staining. As advocated in other histiocytoses, especially those that fail standard therapy [1], the finding of MEK-ERK pathway mutations and/or upregulation by pERK may allow for more directed, targeted therapy with improved outcomes. While targeted therapy is not necessarily curative in most cases [20], it does provide a rapid and sustaining clinical response across the “L” group histiocytosis [16, 19, 32] in which there is immediate clinical response. In addition, it has value in CNS based disease not amenable to complete resection and/or in those cases that do not respond to traditional therapy protocols, including histiocytosis- associated neurodegeneration.

Conclusion

BRAF V600E CNS-JXG neoplasms appear enriched in male children, associated with multifocal parenchymal CNS lesions, background CNS white matter changes, and associated BRAF V600E positive systemic disease manifestations in a subset, which may in turn help expand the spectrum of pediatric ECD in the post-BRAF era. A coherent multidisciplinary approach is needed for best diagnosis, including an accurate and timely pathologic diagnosis, prospective molecular investigation, and subsequent radiographic whole-body staging to evaluate disease extent, similar to adult CNS-ECD. We propose a refinement to diagnosis of CNS-JXG based on pathology, molecular, radiology, and clinical correlation with a comprehensive diagnostic algorithm that has relevance to both clinical management and treatment protocols and is also in line with the current 2016 WHO model of reporting CNS tumors [42]. An initial morphologic diagnosis would first report histology, along with any associated results from a well-validated molecular based immunostain (i.e. BRAF VE1, pERK), if available. Only after DNA-based molecular testing with sensitive testing techniques and clinical/radiographic staging are complete should an integrated final diagnosis be rendered, with description of specific sites of involvement and molecular integration. For example, in case 3 the initial morphologic diagnosis would read as: CNS-JXG, BRAF VE1 immunostain positive. Then the final integrated diagnosis may read as: Pediatric ECD (adult-type) with involvement of brain and long bones, BRAF V600E positive. Such an integrated final diagnosis in CNS-JXG neoplasms will allow for refinement of management with tailored treatment protocols and possible expansion of the spectrum of pediatric ECD, based on pathology, molecular and clinical/radiographic correlation in the post-BRAF era.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- ECD:

-

Erdheim Chester disease

- ERK:

-

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- JXG:

-

Juvenile xanthogranuloma family

- LCH:

-

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen activated pathway kinase

- RDD:

-

Rosai -Dorfman-Destombes disease dorfman disease

References

Abla O, Jacobsen E, Picarsic J, Krenova Z, Jaffe R, Emile JF, Durham BH, Braier J, Charlotte F, Donadieu J et al (2018) Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. Blood 131:2877–2890. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-03-839753

Arnaud L, Hervier B, Neel A, Hamidou MA, Kahn JE, Wechsler B, Perez-Pastor G, Blomberg B, Fuzibet JG, Dubourguet F et al (2011) CNS involvement and treatment with interferon-alpha are independent prognostic factors in Erdheim-Chester disease: a multicenter survival analysis of 53 patients. Blood 117:2778–2782. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-06-294108

Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, Kuo FC, Ligon AH, Stevenson KE, Kehoe SM et al (2010) Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 116:1919–1923. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Colato C, Balter R, Girolomoni G, Schena D (2019) BRAF V600E expression in juvenile xanthogranuloma occurring after Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Dermatol 180:933–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17420

Berres ML, Lim KP, Peters T, Price J, Takizawa H, Salmon H, Idoyaga J, Ruzo A, Lupo PJ, Hicks MJ et al (2014) BRAF V600E expression in precursor versus differentiated dendritic cells defines clinically distinct LCH risk groups. J Exp Med 211:669–683. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20130977

Bostrom J, Janssen G, Messing-Junger M, Felsberg JU, Neuen-Jacob E, Engelbrecht V, Lenard HG, Bock WJ, Reifenberger G (2000) Multiple intracranial juvenile xanthogranulomas. Case report J Neurosurg 93:335–341. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2000.93.2.0335

Botella-Estrada R, Sanmartin O, Grau M, Alegre V, Mas C, Aliaga A (1993) Juvenile xanthogranuloma with central nervous system involvement. Pediatr Dermatol 10:64–68

Burgdorf WH, Zelger B (1996) The non-Langerhans' cell histiocytoses in childhood. Cutis 58:201–207

Castro EC, Blazquez C, Boyd J, Correa H, de Chadarevian JP, Felgar RE, Graf N, Levy N, Lowe EJ, Manning JT Jr et al (2010) Clinicopathologic features of histiocytic lesions following ALL, with a review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol 13:225–237. https://doi.org/10.2350/09-03-0622-oa.1

Chakraborty R, Hampton OA, Abhyankar H, Zinn DJ, Grimes A, Skull B, Eckstein O, Mahmood N, Wheeler DA, Lopez-Terrada D et al (2017) Activating MAPK1 (ERK2) mutation in an aggressive case of disseminated juvenile xanthogranuloma. Oncotarget. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.17521

Chakraborty R, Hampton OA, Abhyankar H, Zinn DJ, Grimes A, Skull B, Eckstein O, Mahmood N, Wheeler DA, Lopez-Terrada D et al (2017) Activating MAPK1 (ERK2) mutation in an aggressive case of disseminated juvenile xanthogranuloma. Oncotarget 8:46065–46070. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.17521

Chang KTE, Tay AZE, Kuick CH, Chen H, Algar E, Taubenheim N, Campbell J, Mechinaud F, Campbell M, Super L et al (2019) ALK-positive histiocytosis: an expanded clinicopathologic spectrum and frequent presence of KIF5B-ALK fusion. Mod Pathol 32:598–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0168-6

Dehner LP (2003) Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life: a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol 27:579–593

Diamond EL, Abdel-Wahab O, Durham BH, Dogan A, Ozkaya N, Brody L, Arcila M, Bowers C, Fluchel M (2016) Anakinra as efficacious therapy for 2 cases of intracranial Erdheim-Chester disease. Blood 128:1896–1898. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-06-725143

Diamond EL, Dagna L, Hyman DM, Cavalli G, Janku F, Estrada-Veras J, Ferrarini M, Abdel-Wahab O, Heaney ML, Scheel PJ et al (2014) Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and clinical management of Erdheim-Chester disease. Blood 124:483–492. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-03-561381

Diamond EL, Durham BH, Haroche J, Yao Z, Ma J, Parikh SA, Wang Z, Choi J, Kim E, Cohen-Aubart F et al (2016) Diverse and targetable kinase alterations drive Histiocytic neoplasms. Cancer discovery 6:154–165. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-15-0913

Diamond EL, Durham BH, Ulaner GA, Drill E, Buthorn J, Ki M, Bitner L, Cho H, Young RJ, Francis JH et al (2019) Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature 567:521–524. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1012-y

Diamond EL, Hatzoglou V, Patel S, Abdel-Wahab O, Rampal R, Hyman DM, Holodny AI, Raj A (2016) Diffuse reduction of cerebral grey matter volumes in Erdheim-Chester disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 11:109–109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0490-3

Diamond EL, Subbiah V, Lockhart AC, Blay JY, Puzanov I, Chau I, Raje NS, Wolf J, Erinjeri JP, Torrisi J et al (2018) Vemurafenib for BRAF V600-mutant Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell Histiocytosis: analysis of data from the histology-independent, phase 2, open-label VE-BASKET study. JAMA Oncol 4:384–388. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5029

Eckstein OS, Visser J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen CE (2019) Clinical responses and persistent BRAFV600E + blood cells in children with LCH treated with MAPK pathway inhibition. Blood. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-10-878363

Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, Horne A, Haroche J, Donadieu J, Requena-Caballero L, Jordan MB, Abdel-Wahab O, Allen CE et al (2016) Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood 127:2672–2681. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636

Ernemann U, Skalej M, Hermisson M, Platten M, Jaffe R, Voigt K (2002) Primary cerebral non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis: MRI and differential diagnosis. Neuroradiology 44:759–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-002-0819-6

Estrada-Veras JI, O'Brien KJ, Boyd LC, Dave RH, Durham B, Xi L, Malayeri AA, Chen MY, Gardner PJ, Alvarado-Enriquez JR et al (2017) The clinical spectrum of Erdheim-Chester disease: an observational cohort study. Blood Adv 1:357–366. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2016001784

Euskirchen P, Haroche J, Emile JF, Buchert R, Vandersee S, Meisel A (2015) Complete remission of critical neurohistiocytosis by vemurafenib. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2:e78. https://doi.org/10.1212/nxi.0000000000000078

Fatobene G, Haroche J, Helias-Rodzwicz Z, Charlotte F, Taly V, Ferreira AM, Abdo ANR, Rocha V, Emile JF (2018) BRAF V600E mutation detected in a case of Rosai-Dorfman disease. Haematologica 103:e377–e379. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.190934

Flach DB, Winkelmann RK (1986) Juvenile xanthogranuloma with central nervous system lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 14:405–411

Fulkerson DH, Luerssen TG, Hattab EM, Kim DL, Smith JL (2008) Long-term follow-up of solitary intracerebral juvenile xanthogranuloma. Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 44:480–485. https://doi.org/10.1159/000180303

Garces S, Medeiros LJ, Patel KP, Li S, Pina-Oviedo S, Li J, Garces JC, Khoury JD, Yin CC (2017) Mutually exclusive recurrent KRAS and MAP2K1 mutations in Rosai-Dorfman disease. Mod Pathol 30:1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.55

Grois N, Prayer D, Prosch H, Lassmann H (2005) Neuropathology of CNS disease in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Brain 128:829–838. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh403

Haroche J, Charlotte F, Arnaud L, von Deimling A, Helias-Rodzewicz Z, Hervier B, Cohen-Aubart F, Launay D, Lesot A, Mokhtari K et al (2012) High prevalence of BRAF V600E mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease but not in other non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Blood 120:2700–2703. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-05-430140

Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile J-F, Arnaud L, Maksud P, Charlotte F, Cluzel P, Drier A, Hervier B, Benameur N et al (2013) Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood 121:1495–1500. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-07-446286

Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, Maksud P, Drier A, Toledano D, Barete S, Charlotte F, Cluzel P, Donadieu J et al (2015) Reproducible and sustained efficacy of targeted therapy with vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-mutated Erdheim-Chester disease. J Clin Oncol 33:411–418. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.57.1950

Haynes ESE, Guo H, Jaffe R, and Picarsic J. (2017) S100 Immunohistochemistry In 65 Localized Juvenile Xanthogranuloma Family Lesions: Understanding Staining Patterns With Clinicopathologic Correlation. Spring 2017 Meeting of the Society for Pediatric Pathology. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology, City, pp 526–562, A543

Hervier B, Haroche J, Arnaud L, Charlotte F, Donadieu J, Neel A, Lifermann F, Villabona C, Graffin B, Hermine O et al (2014) Association of both Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease linked to the BRAF V600E mutation: a multicenter study of 23 cases. Blood. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-12-543793

Holck S, Nielsen HJ, Pedersen N, Larsson LI (2015) Phospho-ERK1/2 levels in cancer cell nuclei predict responsiveness to radiochemotherapy of rectal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 6:34321-34328

Janssen D, Harms D (2005) Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the Kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol 29:21–28

Khan MR, Ashraf MS, Belgaumi AF (2017) Erdheim Chester disease–an unusual presentation of a rare histiocytic disease in a 3-year old boy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol J 2:59–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phoj.2017.09.004

Kim S, Lee M, Shin HJ, Lee J, Suh YL (2016) Coexistence of intracranial Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease in a pediatric patient: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 32:893–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-015-2929-6

Kumandas S, Kurtsoy A, Canoz O, Patiroglu T, Yikilmaz A, Per H (2007) Erdheim Chester disease: cerebral involvement in childhood. Brain Dev 29:227–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2006.08.013

Lee LH, Gasilina A, Roychoudhury J, Clark J, McCormack FX, Pressey J, Grimley MS, Lorsbach R, Ali S, Bailey M et al (2017) Real-time genomic profiling of histiocytoses identifies early-kinase domain BRAF alterations while improving treatment outcomes. JCI Insight 2:e89473. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.89473

Lopez Nunez O, Schmitt L, Picarsic J (2018 ) Diagnostic Value of BRAF VE1 Immunohistochemistry as a Reliable Marker of Neoplasms Harboring BRAF V600E Mutation in Pediatric and Histiocytic Neoplasms. A17. 2018 SPP fall abstracts. Pediatr Dev Pathol 0: 1093526618806423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1093526618806423

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Mass E, Jacome-Galarza CE, Blank T, Lazarov T, Durham BH, Ozkaya N, Pastore A, Schwabenland M, Chung YR, Rosenblum MK et al (2017) A somatic mutation in erythro-myeloid progenitors causes neurodegenerative disease. Nature 549:389–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23672

Mastropolo R, Close A, Allen SW, McClain KL, Maurer S, Picarsic J (2019) BRAF V600E mutated Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis with response to BRAF inhibitor. Blood Adv 3:1848–1853. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000093

McClain KL, Picarsic J, Chakraborty R, Zinn D, Lin H, Abhyankar H, Scull B, Shih A, Lim KPH, Eckstein O et al (2018) CNS Langerhans cell histiocytosis: common hematopoietic origin for LCH-associated neurodegeneration and mass lesions. Cancer 124:2607–2620. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31348

Meyer P, Graeff E, Kohler C, Munier F, Bruder E (2018) Juvenile xanthogranuloma involving concurrent iris and skin: clinical, pathological and molecular pathological evaluations. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 9:10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoc.2017.09.004

Orsey A, Paessler M, Lange BJ, Nichols KE (2008) Central nervous system juvenile xanthogranuloma with malignant transformation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50:927–930. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21252

Pan Z, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK (2017) CNS Erdheim-Chester disease: a challenge to diagnose. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 76:986–996. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlx095

Picarsic J, Alaggio R, Jaffe R, Diamond EL, Durham B, Abdel-Wahab O (2019) Abstracts from the 34th annual meeting of the Histiocyte society Lisbon, Portugal, October 22–23, 2018. 66:e27548. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27548

Picarsic J, Jaffe R (2017) Pathology of Histiocytic disorders and neoplasms and related disorders. In: Abla O. JGe (ed) Histiocytic disorders. Springer, City, pp 3–50

Pinney SS, Jahan-Tigh RR, Chon S (2016) Generalized eruptive histiocytosis associated with a novel fusion in LMNA-NTRK1. Dermatol Online J 22.

Richardson TE, Wachsmann M, Oliver D, Abedin Z, Ye D, Burns DK, Raisanen JM, Greenberg BM, Hatanpaa KJ (2018) BRAF mutation leading to central nervous system rosai-dorfman disease. Ann Neurol 84:147–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25281

Rollins BJ (2015) Genomic alterations in Langerhans cell Histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 29:839–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.004

Ruby KN, Deng AC, Zhang J, LeBlanc RE, Linos KD, Yan S (2018) Emperipolesis and S100 expression may be seen in cutaneous xanthogranulomas: a multi-institutional observation. J Cutan Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13285

Tamir I, Davir R, Fellig Y, Weintraub M, Constantini S, Spektor S (2013) Solitary juvenile xanthogranuloma mimicking intracranial tumor in children. J Clin Neurosci 20:183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.019

Techavichit P, Sosothikul D, Chaichana T, Teerapakpinyo C, Thorner PS, Shuangshoti S (2017) BRAF V600E mutation in pediatric intracranial and cranial juvenile xanthogranuloma. Hum Pathol 69:118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2017.04.026

Tittman SM, Nassiri AM, Manzoor NF, Yawn RJ, Mobley BC, Wellons JC, Rivas A (2019) Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the cerebellopontine angle: a case report and review of the literature. Otolaryngol Case Rep 12:100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xocr.2019.100124

Wang B, Jin H, Zhao Y, Ma J (2016) The clinical diagnosis and management options for intracranial juvenile xanthogranuloma in children: based on four cases and another 39 patients in the literature. Acta Neurochir 158:1289–1297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-016-2811-7

Weitzman S, Jaffe R (2005) Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer 45:256–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20246

Zelger BW, Sidoroff A, Orchard G, Cerio R (1996) Non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. A new unifying concept. Am J Dermatopathol 18:490–504

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Lori Schmitt, ASAP for her technical excellence in the validation and quality of BRAF V600E immunostain (VE1) and all of the clinicians and pathologists who allowed us to review their rare and unique cases in consultation, including, but not limited to Dr. Justine Kahn at Columbia University and Dr. Eva LØbner Lund at Rigshospitalet.

Funding

The project described was supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number UL1TR000005 and CA88041 and was also supported by the Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JP and MS designed study and drafted manuscript, TP, HZ, MF, TP, MW, LS, BH, GG, YF, MW, BM, PS, MLS, ELD, RJ, and KS contributed cases and help revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A waiver of HIPAA Authorization and waiver of consent were approved for this study by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (PRO12110055).

Consent for publication

Not required; see above.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Picarsic, J., Pysher, T., Zhou, H. et al. BRAF V600E mutation in Juvenile Xanthogranuloma family neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS-JXG): a revised diagnostic algorithm to include pediatric Erdheim-Chester disease. acta neuropathol commun 7, 168 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0811-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0811-6