Abstract

Blast-related traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been a common cause of injury in the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Blast waves can damage blood vessels, neurons, and glial cells within the brain. Acutely, depending on the blast energy, blast wave duration, and number of exposures, blast waves disrupt the blood-brain barrier, triggering microglial activation and neuroinflammation. Recently, there has been much interest in the role that ongoing neuroinflammation may play in the chronic effects of TBI. Here, we investigated whether chronic neuroinflammation is present in a rat model of repetitive low-energy blast exposure. Six weeks after three 74.5-kPa blast exposures, and in the absence of hemorrhage, no significant alteration in the level of microglia activation was found. At 6 weeks after blast exposure, plasma levels of fractalkine, interleukin-1β, lipopolysaccharide-inducible CXC chemokine, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, and vascular endothelial growth factor were decreased. However, no differences in cytokine levels were detected between blast-exposed and control rats at 40 weeks. In brain, isolated changes were seen in levels of selected cytokines at 6 weeks following blast exposure, but none of these changes was found in both hemispheres or at 40 weeks after blast exposure. Notably, one animal with a focal hemorrhagic tear showed chronic microglial activation around the lesion 16 weeks post-blast exposure. These findings suggest that focal hemorrhage can trigger chronic focal neuroinflammation following blast-induced TBI, but that in the absence of hemorrhage, chronic neuroinflammation is not a general feature of low-level blast injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Military personnel exposed to blast overpressures are at risk of developing behavioral and cognitive abnormalities [11]. Acutely, several studies in animal models have shown that blast exposure induces brain inflammation and increased levels of pro-inflammatory factors. Infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes is observed in the brain parenchyma within 1 h post-blast exposure [53]. In rats, a single 551-kPa blast exposure induced glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), S100β (an astrocytic marker), cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, interleukin (IL)-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and these changes were present by 1 h and remained detectable at 3 weeks post-injury [53]. Similarly, GFAP levels were significantly higher in all measured brain regions of rats exposed to 133.8-kPa blast overpressure [26]. In another study, a 120-kPa blast triggered release of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10, and erythropoietin (EPO) as early as 3 h after injury, and peak levels were reached at 24 h before they diminished by 48 h [33]. Moreover, a 129-kPa blast induced transcriptional upregulation of the proinflammatory interferon (IFN)-γ and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 by 4 h post-blast, and increased levels of these proteins were detected 24 h post-blast while strong Iba1-immunoreactive microglial cell activation was detected at 2 weeks post-blast [8]. Elevated levels of IFN-γ and IL-6 have also been found in the amygdala and ventral hippocampus, together with an increased number of Iba1-expressing activated microglia following blast injury [26].

A cDNA microarray analysis of the brains of mice exposed to a 142-kPa blast showed significant upregulation of several interleukin receptors in the midbrain [55]. In the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, the expression of IL receptors was significantly reduced, whereas the expression of TNF-α and its receptors was increased [55]. In rats subjected to multiple 138-kPa blast exposures (5×), plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) were significantly elevated after 2 h compared to levels in sham controls and rats exposed to a single blast [27]. By day 22 post-injury, animals exposed to either a single blast or multiple blasts had significantly higher levels of VEGF, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), neurofilament H (NFH), and GFAP than did those in the non-injured control groups [27]. At 1 day post-blast exposure, increased GFAP immunoreactivity was observed in the hippocampus of animals exposed to a single blast, whereas no such increase was seen in animals exposed to multiple blasts [27]. However, by day 22, an apparent increase in GFAP immunoreactivity was observed in the hippocampus of the multiple blast-exposed rats. In both the single and multiple blast-exposed groups, increased apoptosis was found in the hippocampal hilus [27] .

In a temporal evaluation of cytokines in rat serum after a single 117-kPa blast exposure, a significant decrease in IL-1α expression was observed at 3 h as well as a decrease in M-CSF expression at 24 h, an increase in EPO at 48 h, and decreased levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and EPO along with increased levels of VEGF and macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) at 72 h post-blast [44]. Blast injury (142 kPa) in stressed rats resulted in elevated levels of serum corticosterone, NFH, NSE, GFAP, and VEGF compared to levels in non-blast-exposed controls 2 months post-injury. The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (PFC) also contained increased numbers of apoptotic cells (TUNEL-positive) and elevated levels of GFAP, S100β, Iba1, VEGF, IL-6, IFN-γ, and phosphorylated tau [32]. In humans, 35- to 81-kPa blast exposures result in increased levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the serum that were maintained for 24 h [18].

These data altogether suggest that acute blast exposure induces brain inflammation and increased levels of pro-inflammatory factors. Acute inflammation has long been considered a transient phenomenon in many forms of TBI. However, there is accumulating evidence that the inflammatory response after TBI may persist [14]. Indeed, studies in animals document persistent inflammation in brain after TBI [14]. Postmortem human studies find inflammatory changes that can persist for years after TBI [24], and a recent study using positron emission tomography to image a ligand that targets microglia found increased microglial activation up to 17 years after injury [43] .

We previously reported that rats exposed to low-level blast overpressures (74.5 kPa) develop a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like phenotype associated with chronic brain vascular degeneration and rarely hemorrhagic brain cortical tears that follow the lines of penetrating vessels [17, 49]. In the present study, we investigated whether three 74.5-kPa blast exposures can induce chronic microglial activation and increase the levels of pro-inflammatory factors in brain. Our results show that under this blast protocol and in the absence of vascular disruption, low-level blast exposures do not alter the microglial cell density nor microglial activation in the hippocampus and prelimbic cortex and do not significantly alter the levels of cytokines involved in neuroinflammation (over 6–40 weeks post-blast). However, in the presence of focal hemorrhage, neuroinflammation with increased microglial activation and astrocytosis was observed 16 weeks post-blast exposure. These results show that neuroinflammation is induced by leakage of blood elements from a fragile vasculature into the brain parenchyma. However, in the absence of hemorrhage, chronic neuroinflammation is not a general feature of low-level blast injury.

Materials and methods

Animals and blast exposure

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research/Naval Medical Research Center, Silver Spring, MD. Long Evans rats were exposed to three 74.5-kPa (10.8 psi) blasts of compressed air in a shock tube under isoflurane anesthesia at 10 weeks of age as previously described [1]. Rats were randomly assigned to sham or blast conditions with the head facing the blast exposure without any body shielding resulting in a full body exposure to the blast wave. One exposure per day was administered for three consecutive days. Control animals were anesthesized and placed inside the shock tube but not exposed to blast overpressures. For stereology, animals (n = 5/group) were euthanized by cardiac perfusion 6 weeks post-blast exposure with cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For cytokine analyses, blast-exposed and control animals were euthanized with CO2 at 6 and 40 weeks post-blast exposure.

Quantitative morphometric analyses of microglial phenotypes in the hippocampus and prelimbic cortex

Vibratome-cut coronal sections (50 μm-thick) from 4% paraformaldehyde-perfused brains of blast-exposed and control animals were sampled every 500 μm throughout the brain. Sections were rinsed with PBS, blocked with 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 5% goat serum (TBS-TGS) for 1 h, and incubated overnight with rabbit anti-Iba1 antibodies (ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 [41], 1:300, Wako, Japan) in TBS-TGS at room temperature. After 6 washes with PBS over a period of 1 h, sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:300, Pierce, Waltham, MA) for 2 h in TBS-TGS and rinsed with PBS. Microglial immunostaining was visualized by incubation with 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), 0.015% H2O2 in 0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM imidazole, pH 7.0 at room temperature. Stereology of prelimbic (interaural, 12.00 mm) and hippocampal microglia (interaural, 4.44–5.76 mm) was performed using the MBF StereoInvestigator software with the Optical Fractionator probe (Williston, VT) [38]. Stereologic analyses were done with the investigator blinded to the experimental condition. Areas of interest were traced using an Olympus PlanFI 4×/0.13 objective lens on an Olympus BX51 microscope, and a PlanApo 60×/1.40 oil-immersion objective lens was used for cell counting. Sampling grids of 500 × 400 μm were randomly placed over the hippocampal and prelimbic cortical regions, and contained an optical disector of 80 × 80 μm, within which cell numbers were counted. A 1-μm guard zone was set at the top and bottom of each section. Microglial profiles contained either within the frame or touching the permitted green lines were counted, whereas those that touched the forbidden red margins were excluded. The morphology, according to the microglial phenotype, of each counted cell was also noted (types 1–4: ramified, primed, reactive, and ameboid) [30, 31, 46, 48, 50, 54]. Analysis of microglia activation in the hippocampus was further performed by immunohistochemical determination of MHC class II antigen (MHCII) expression in Iba1-positive cells. Sections (interaural, 5.64 mm) from the 5 blast-exposed and 5 control animals described above were immunostained with rabbit anti-Iba1 and mouse anti-rat MHC class II antibodies (1:200, Novus Biologicals, Littleton CO, USA) as described above. Immunostaining was detected with species-specific AlexaFluor 488- and 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:300; Molecular Probes, Eugene OR, USA). Nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The relative fraction of MHCII+/Iba1+ cells was determined in both hemispheres.

Immunoassay for selected rat cytokines

Levels of selected cytokines in plasma and regional brain extracts taken from control and blast-exposed animals at 6 and 40 weeks post-blast exposure were measured (n = 5/group). Brains were regionally dissected and extracts were prepared from the left and right posterior cortex (association, auditory, visual, and entorhinal cortices), anterior cortex (prefrontal, motor, somatosensory, and insular cortices), hippocampus, and amygdala. The tissues were homogenized in a solution of 0.1 M Tris HCl, pH 7.6, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 1% Triton X-100 supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000×g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants collected for analysis. The total protein concentration was determined with the BCA reagent (Pierce, Waltham, MA), and the protein concentration of the brain samples was adjusted to 1 μg/μl. The levels of the selected cytokines/chemokines were determined using a multiplexed bead-based immunoassay [23], which has been extensively used for the study of cytokine dysregulation in rat models of blast-induced TBI [33, 44, 58] and allows for simultaneous detection of cytokines/chemokines involved in inflammation. The Milliplex MAP Rat Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel-Premixed 2 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used in our study to analyze 27 targets namely IFN-γ, interleukins IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-17A and IL-18, IFN γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10), leptin, lipopolysaccharide-inducible CXC chemokine (LIX), M-CSF, MCP-1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-2, RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T-Cell Expressed and Secreted), TNF-α, EPO, VEGF, epidermal growth factor (EGF), C-C motif chemokine 11 (eotaxin/CCL11), chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 1 (CXCL1/GRO/KC), and fractalkine.

Statistical analyses

Between group comparisons were made using unpaired Student’s t tests and are reported without correction for multiple comparisons and after a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical tests were performed using the program GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) or SPSS 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Similar microglial activation in control and blast-exposed animals

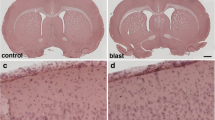

Brains of 16 week-old rats were analyzed 6 weeks post-blast exposures, a time by which chronic inflammation should be well established. No evidence of the presence of hemorrhages was observed on freshly-cut sections nor on hematoxylin-eosin (HE)-stained sections. General microscopic observations of Iba1-immunoreactive cells throughout the brain did not reveal major differences in the microglial cell density or phenotype morphologies between sequential brain sections from control and blast-exposed animals and did not identify focal regions of microgliosis (Fig. 1).

A quantitative stereologic analysis of Iba1-immunolabeled microglia was performed to evaluate the relative distribution and abundance of microglial phenotypes in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of blast-exposed and control animals (Fig. 2). Distinct morphological phenotypes were observed in the selected areas corresponding to the previously described microglial phenotypes associated with different states of activation including ramified, primed, reactive, and ameboid microglia (types 1–4, respectively; Fig. 2) [30, 31, 46, 48, 50, 54]. No statistically significant differences were observed in the total microglial populations in the analyzed brain regions of control and blast-exposed animals. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the relative numbers of microglial subtypes, with the most abundant being the ramified (type 1) and primed (type 2) microglia (Figs. 1 and 2).

Similar local densities of microglia and microglial subtypes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex 6 weeks following blast exposure. Estimated densities of total microglia and microglial subtypes are shown for the hippocampus (a) and prefrontal cortex (b). Panel (c) shows examples of microglial subtypes. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). There was no statistically significant difference between blast and control

It is well known that brain injury triggers the proliferation and activation of quiescent ramified microglia that transform into proinflammatory brain macrophages (M1) devoid of branching processes and with upregulated expression of MHCII and other surface molecules such as CD86, and Fcγ receptors [7]. The negligible presence of MHCII+ Iba1+ cells in the hippocampus (<1% of total Iba1+ cells) of blast-exposed animals (similar to controls) further confirms the lack of neuroinflammation induced by the blast waves 6 weeks post-exposure (Fig. 3).

Lack of activated proinflammatory Iba1+ MHCII+ microglia in the hippocampus of blast-exposed animals (6 weeks post-blast exposure). Iba1, green; MHCII, red; DAPI, blue. Similar negligible presence of MHCII+ microglia (<1% of Iba1+ cells) was observed in the hippocampus of blast exposed (a-c) and control animals (d-f). Merged images correspond to Panels c and f, respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. Panels g-i show MHCII+ cells residing in the meninges surrounding the motor cortex of a blast-exposed animal (positive control). Merged image is shown in Panel i. Scale bar, 20 μm

Limited alterations in plasma or brain inflammasome after low-level blast exposure

We also investigated the effects of low-level blast overpressures on the cerebral inflammasome in the amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cortex (prefrontal, motor, somatosensory, and insular cortices), and posterior cortex (association, auditory, visual, and entorhinal cortices) of both hemispheres and in plasma at 6 weeks and 40 weeks post-blast exposure (Tables 1 and 2, Figs. 4 and 5). As shown in Table 1, at 6 weeks post-blast exposure there were significant or near significant 1.4- to 1.8-fold decreases in the levels of fractalkine, IL-1β, leptin, LIX, MIP-1, and VEGFα in plasma. However, none of these changes was replicated in plasma at 40 weeks post-blast, where no cytokine differences between blast and control were detected (Fig. 5, Table 2). In brain, isolated changes were seen in selected cytokines at 6 weeks following blast exposure. However, none of these changes was replicated in both hemispheres (Table 1) or at 40 weeks post-blast exposure (Table 2). In addition, if a Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons (using p = 0.0002 for significance) none of the comparisons would reach statistical significance. Interestingly, as found in plasma in most cases where differences in brain were noted, the levels were decreased in blast-exposed animals. For example, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5, the proinflammatory IL-1β and IL-6 as well as the anti-inflammatory IL-10 were not significantly changed in the various brain areas except for a decrease of IL-6 in the right hippocampus. LIX was also decreased in the amygdala and right anterior cortex (Table 1). However, at 40 weeks there were no significant changes in the same cytokines in brain (Table 2). Collectively, these data provide little evidence for significant brain inflammation over a period of 6–40 weeks post-blast.

Selected cytokines in the brains of control and blast-exposed animals (6 weeks post-blast exposure). Shown are levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 in the left (L) or right (R) hemispheres of the indicated brain regions. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences indicated represent unpaired t-tests

Selected cytokines in the brains of control and blast-exposed animals (40 weeks post-blast exposure). Shown are levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 in the left (L) or right (R) hemispheres of the indicated brain regions. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences indicated represent unpaired t-tests

Focal hemorrhage triggers microglial activation in the blast-exposed brain

Interestingly, at 16 weeks post-blast exposure (3 × 74.5 kPa), the brain of a 6-month-old animal (part of a different cohort previously reported [49]) exhibited an amorphous cellular mass resembling an infiltrated clot within a scar tissue-tear associated with the perirhinal vein and presented with diffuse microgliosis within the injured hemisphere (Fig. 6). Microgliosis presented a gradient of reactivity including ameboid morphologies (types 3 and 4) that extended along the scarred lesion from the temporal association cortex through the CA1 stratum radiatum where the clot was found (Figs. 6 and 7). The scar of the focal tear was lined in its immediate vicinity by activated astrocytes and an area devoid of microglia (Figs. 6c-f, 7a), indicating that the local microglia are highly susceptible to the initial blast overpressure experienced in the region immediately adjacent to a penetrating vessel. This region was adjoined by an area of clear type 3 and 4 microgliosis. Type 4 ameboid microglia were predominantly found immediately next to the clot, whereas most cells in the cortical region exhibited the morphologies of types 2 and 3 activated cells (Figs. 6 and 7).

Focal tear and hemorrhage associated with microglia activation in the rat brain 16 weeks post-blast exposures. HE staining (a, b). Black arrows indicate location of a blood clot. Scale bars: (a), 500 μm; (b), 200 μm. Brain sections were stained with Iba1 (c) and GFAP (d) and counterstained with DAPI (e). Arrows in Panel (c) indicate the areas next to the focal tissue tear devoid of microglia. Letters inside Panel (c) indicate the relative location of areas illustrated in Fig. 7. Merged image (f). Scale bar, 200 μm

Distribution of microglia in the vicinity of a blast-induced hemorrhagic focal tear. The relative localization of the different panels in the brain of the blast-exposed animal is indicated in Fig. 6 (e). Panels (a-c), Iba 1 (green) and GFAP (red) immunostaining. Absence of microglia (green) in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus immediately next to the blast-induced tear (a). Presence of reactive and ameboid microglia in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (b) and in the stratum lucidum (c) of the hippocampus, away from the tear. Microglial activation gradient, Iba 1 (green) immunostaining (d-f). Primed and reactive (types 2–3) microglia in the cortex (d, e). Ameboid (type 4) microglia in the region associated with the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus away from the tear (f). Scale bar, 50 μm

Discussion

Acute inflammation is a recognized feature following TBI induced by mechanical trauma [47] with recent evidence that a chronic neuroinflammatory component may also develop and contribute to the late effects of TBI including the development of neurodegnerative diseases [14]. Inflammation is also a component of acute blast injury [12]. Activation of resident microglia, influx of peripheral leukocytes, and release of proinflammatory mediators are early events of this process. Microglia are activated by thrombin through MAPK signaling pathways via the proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) [16, 39]. Microglia can also be activated through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the receptor for advanced glycosylation endproducts via danger-associated molecular signals (ATP, neurotransmitters, nucleic acids, heat shock proteins, and high-mobility group box 1 proteins) released by necrotic cells [10, 40, 52]. Microglial activation leads to increased production of TNF-α and IL-1β, which induces neuronal apoptosis [57]. Microglia are also involved in clearance of cell debris and phagocytosis of blood components, with a central role in hematoma resolution.

Explosive blasts rapidly generate very high levels of kinetic energy that dissipate as supersonic pressure waves to cause blast-induced TBI [13, 37, 42]. In the brain parenchyma, these high-energy, high-velocity blast waves can also cause substantial damage to blood vessels as well as to neuronal and glial cell bodies and their processes [4,5,6, 17, 19, 28, 49]. Prolonged but not short-duration high-energy blast waves (620–1570 kPa) result in the acute onset of neuroinflammation and of increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain [9]. Depending on the intensity of the blast, TBI may include an early-onset diffuse cerebral edema and delayed vasoconstriction [3, 34,35,36]. Injury secondary to blast-induced TBI involves vascular remodeling, neuroinflammation, and gliosis that are visible several months after the initial injury [6, 28, 37, 51].

In contrast to these findings after high-energy blast exposures, our experiments with lower level energy blast exposures (74.5 kPa) did not demonstrate the presence of chronic neuroinflammation 6 weeks post-blast exposure. Immunohistochemical analyses of brains from blast-exposed animals without any evidence of vascular leakage did not show obvious microgliosis, as shown by the relatively low abundance of Iba1+ reactive or amoeboid microglia (types 3 and 4) expressing MHCII, and did not present major alterations in the brain inflammasome even at 40 weeks post-blast exposure. Curiously, lack of inflammation after mild brain injury has also been reported in a mouse model of closed head injury using a standardized weight-drop technique [45]. The lack of inflammation observed in our animals indicates that low-energy blast exposures (74.5 kPa) are not always sufficient to sustain chronic neuroinflammation. In a murine model system, microglial activation associated with microdomains of vascular disruption (tight junction injury) has been observed 45 min post 105.5-kPa blast exposure [22]. However, by 14 days post-blast, elevated levels of TNF-α were only sustained in animals exposed to three repetitive blasts, suggesting that even at higher blast energy, repetitive exposures are required to promote more persistent neuroinflammatory changes in the CNS [22].

In blast-induced TBI, vascular blood leakage may be a requirement for the progression and persistence of neuroinflammation. This is also supported by an observation in a blast-exposed animal that exhibited an infiltrated clot within scarred tissue 16 weeks post-blast exposure that was associated with overwhelming microglial activation (Figs. 6 and 7). As the clot was found 16 weeks post-blast exposure, it could be presumed that the vascular leakage occurred at a much later time after the last blast exposure, most likely as a result of a progressive blast-induced vascular degenerative processes, leading to induced vascular fragility, subsequent rupture, and blood leakage [17]. We have previously reported the selective vulnerability of penetrating vessels that follow the patterns of blast-induced focal tears and of the associated microvasculature to 74.5-kPa blast exposures. Vascular injuries are present acutely at 24 h after blast exposure and lead to a chronic vascular degenerative processes that can lead to vascular rupture later in life [17].

Comparison of high- and lower-energy blast-induced TBI clearly indicates that BBB leakage, microglial activation, and increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines depend on the blast overpressure energy and the number of exposures. Acutely, after 72 h, animals exposed to 74.5-kPa blasts present pathological alterations that mainly included blood leakage from the choroid plexus into the lateral ventricles, focal non-hemorrhagic tissue tears, and vascular alterations [17, 49]. In other rat models, blast-induced BBB leakage appeared preferentially at higher blast pressures (>110-kPa), as it was shown that extensive leakage occurred in all brain regions but preferentially in the thalamus, striatum, hippocampus, and occipital cortex [25, 29]. However, limited leakage, mainly through the chorionic plexus, was observed after exposure to 72-kPa blasts [25, 29, 49]. Kawoos et al. [29] also showed that there is a qualitative relationship between BBB leakage and increased intracerebral pressure (ICP), through which the ICP levels and sustainability depend also on blast intensity and the number of blast exposures. As blast induces an early vasodilation (as evidenced by enlarged blood vessel diameters [25]), the intravascular forces exercised by the pressurized circulating blood could damage the vascular smooth muscle and endothelial layers [2, 17, 19, 20, 25, 29, 49, 56]. Through buckling, it could induce vascular tortuosity [21] and through subsequent axial stretch [15], generate vascular strictures [17, 49]. In small vessels, endothelial damage can also lead to a breakdown of the BBB and blood leakage [25, 29]. In large vessels, endothelial damage could trigger chronic vascular disease through vascular remodeling by induction of neointima formation, neointima thickening, restenosis, aneurysm formation, plaque deposition, vascular occlusion, thromboembolism, and vascular rupture. Therapeutic approaches aimed at preventing or reversing vascular damage may improve the chronic neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with blast-induced TBI.

Conclusions

Recently much interest has been generated in the role of ongoing neuroinflammation in the chronic effects of TBI. We investigated whether chronic neuroinflammation was present in a rat model of repetitive low-energy blast exposure. No significant alterations in the levels of neuroinflammatory indicators (microglia proliferation and activation as well as pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine concentrations) were observed in rats 6-40 weeks after three 74.5-kPa blast exposures. Microgliosis and microglial activation were observed in one animal associated with vascular blood leakage 16 weeks post-blast, most likely due to chronic vascular degeneration. Thus, extravasation of blood elements may be a trigger for neuroinflammation in blast-induced TBI. However in the absence of hemorrhage, chronic neuroinflammation does not appear to be a long-term consequence of low-level blast injury.

References

Ahlers ST, Vasserman-Stokes E, Shaughness MC, Hall AA, Shear DA, Chavko M, McCarron RM, Stone JR (2012) Assessment of the effects of acute and repeated exposure to blast overpressure in rodents: toward a greater understanding of blast and the potential ramifications for injury in humans exposed to blast. Front Neurol 3:32

Alford PW, Dabiri BE, Goss JA, Hemphill MA, Brigham MD, Parker KK (2011) Blast-induced phenotypic switching in cerebral vasospasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:12705–12710. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1105860108

Armonda RA, Bell RS, Vo AH, Ling G, DeGraba TJ, Crandall B, Ecklund J, Campbell WW (2006) Wartime traumatic cerebral vasospasm: recent review of combat casualties. Neurosurgery 59:1215–1225; discussion 1225. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000249190.46033.94

Cernak I, Savic J, Ignjatovic D, Jevtic M (1999) Blast injury from explosive munitions. J Trauma 47:96–103

Cernak I, Wang Z, Jiang J, Bian X, Savic J (2001) Cognitive deficits following blast injury-induced neurotrauma: possible involvement of nitric oxide. Brain Inj 15:593–612

Cernak I, Wang Z, Jiang J, Bian X, Savic J (2001) Ultrastructural and functional characteristics of blast injury-induced neurotrauma. J Trauma 50:695–706

Cherry JD, Olschowka JA, O'Banion MK (2014) Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. J Neuroinflammation 11:98. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-11-98

Cho HJ, Sajja VS, Vandevord PJ, Lee YW (2013) Blast induces oxidative stress, inflammation, neuronal loss and subsequent short-term memory impairment in rats. Neuroscience 253:9–20. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.08.037

Eftaxiopoulou T, Barnett-Vanes A, Arora H, Macdonald W, Nguyen TT, Itadani M, Sharrock AE, Britzman D, Proud WG, Bull AMet al (2016) Prolonged but not short-duration blast waves elicit acute inflammation in a rodent model of primary blast limb trauma. Injury 47: 625–632 Doi:10.1016/j.injury.2016.01.017

ElAli A, Rivest S (2016) Microglia ontology and signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol 4:72. doi:10.3389/fcell.2016.00072

Elder GA (2015) Update on TBI and cognitive impairment in military veterans. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 15:68. doi:10.1007/s11910-015-0591-8

Elder GA, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Stone JR, Dickstein DL, Haghighi F, Hof PR, Ahlers ST (2015) Vascular and inflammatory factors in the pathophysiology of blast-induced brain injury. Front Neurol 6: 48 Doi:10.3389/fneur.2015.00048

Elder GA, Mitsis EM, Ahlers ST, Cristian A (2010) Blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am 33:757–781

Faden AI, Loane DJ (2015) Chronic neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury: Alzheimer disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or persistent neuroinflammation? Neurotherapeutics 12:143–150. doi:10.1007/s13311-014-0319-5

Fatemifar F, Han H-C (2016) Effect of axial stretch on lumen collapse of arteries. J Biomech Eng 138. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4034785

Fujimoto S, Katsuki H, Ohnishi M, Takagi M, Kume T, Akaike A (2007) Thrombin induces striatal neurotoxicity depending on mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in vivo. Neuroscience 144:694–701. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.049

Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Janssen PL, Yuk FJ, Anazodo PC, Pricop PE, Paulino AJ, Wicinski B, Shaughness MC, Maudlin-Jeronimo E et al (2014) Selective vulnerability of the cerebral vasculature to blast injury in a rat model of mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathologica Commun 2: 67 Doi:10.1186/2051-5960-2-67

Gill J, Motamedi V, Osier N, Dell K, Arcurio L, Carr W, Walker P, Ahlers S, LoPresti M, Yarnell A (2017) Moderate blast exposure results in increased IL-6 and TNFalpha in peripheral blood. Brain, behavior, and immunity. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.015

Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA, Zhang XL, Velisek L, Sullivan JA, Upreti C, Kracht JM, Ericsson M, Wojnarowicz MW et al (2012) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model. Sci Transl med:4: 134ra160

Hald ES, Alford PW (2014) Smooth muscle phenotype switching in blast traumatic brain injury-induced cerebral vasospasm. Transl Stroke Res 5:385–393. doi:10.1007/s12975-013-0300-3

Han HC (2012) Twisted blood vessels: symptoms, etiology and biomechanical mechanisms. J Vasc Res 49:185–197. doi:10.1159/000335123

Huber BR, Meabon JS, Hoffer ZS, Zhang J, Hoekstra JG, Pagulayan KF, McMillan PJ, Mayer CL, Banks WA, Kraemer BCet al (2016) Blast exposure causes dynamic microglial/macrophage responses and microdomains of brain microvessel dysfunction. Neuroscience 319: 206–220 Doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.022

Hulse RE, Kunkler PE, Fedynyshyn JP, Kraig RP (2004) Optimization of multiplexed bead-based cytokine immunoassays for rat serum and brain tissue. J Neurosci Methods 136:87–98. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.12.023S0165027004000081

Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W (2013) Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 136:28–42. doi:10.1093/brain/aws322

Kabu S, Jaffer H, Petro M, Dudzinski D, Stewart D, Courtney A, Courtney M, Labhasetwar V (2015) Blast-associated shock waves result in increased brain vascular leakage and elevated ROS levels in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. PLoS One 10:e0127971. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127971

Kamnaksh A, Kovesdi E, Kwon SK, Wingo D, Ahmed F, Grunberg NE, Long J, Agoston DV (2011) Factors affecting blast traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 28:2145–2153

Kamnaksh A, Kwon SK, Kovesdi E, Ahmed F, Barry ES, Grunberg NE, Long J, Agoston D (2012) Neurobehavioral, cellular, and molecular consequences of single and multiple mild blast exposure. Electrophoresis 33:3680–3692. doi:10.1002/elps.201200319

Kaur C, Singh J, Lim MK, Ng BL, Yap EP, Ling EA (1995) The response of neurons and microglia to blast injury in the rat brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 21:369–377

Kawoos U, Gu M, Lankasky J, McCarron RM, Chavko M (2016) Effects of exposure to blast overpressure on intracranial pressure and blood-brain barrier permeability in a rat model. PLoS One 11:e0167510. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167510

Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A (2011) Physiology of microglia. Physiol Rev 91:461–553. doi:10.1152/physrev.00011.2010

Kreutzberg GW (1996) Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci 19:312–318

Kwon SK, Kovesdi E, Gyorgy AB, Wingo D, Kamnaksh A, Walker J, Long JB, Agoston DV (2011) Stress and traumatic brain injury: a behavioral, proteomics, and histological study. Front Neurol 2:12

Li Y, Chavko M, Slack JL, Liu B, McCarron RM, Ross JD, Dalle Lucca JJ (2013) Protective effects of decay-accelerating factor on blast-induced neurotrauma in rats. Acta Neuropathologica Commun 1:52. doi:10.1186/2051-5960-1-52

Ling G, Bandak F, Armonda R, Grant G, Ecklund J (2009) Explosive blast neurotrauma. J Neurotrauma 26:815–825

Ling G, Ecklund J (2007) Neuro-critical care in modern war. J Trauma 62:S102. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318065b44200005373-200706001-00078

Ling GS, Ecklund JM (2011) Traumatic brain injury in modern war. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 24:124–130. Doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834458da

Mayorga MA (1997) The pathology of primary blast overpressure injury. Toxicology 121: 17-28 Doi S0300483X97036524

Morgan JT, Chana G, Pardo CA, Achim C, Semendeferi K, Buckwalter J, Courchesne E, Everall IP (2010) Microglial activation and increased microglial density observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in autism.Biol psychiatry 68: 368-376 Doi S0006-3223(10)00497-X [pii] Doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.024

Ohnishi M, Katsuki H, Fujimoto S, Takagi M, Kume T, Akaike A (2007) Involvement of thrombin and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in hemorrhagic brain injury. Exp Neurol 206:43–52. Doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.030

Ohnishi M, Katsuki H, Fukutomi C, Takahashi M, Motomura M, Fukunaga M, Matsuoka Y, Isohama Y, Izumi Y, Kume T et al (2011) HMGB1 inhibitor glycyrrhizin attenuates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced injury in rats. Neuropharmacology 61:975–980. Doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.026

Ohsawa K, Imai Y, Kanazawa H, Sasaki Y, Kohsaka S (2000) Involvement of Iba1 in membrane ruffling and phagocytosis of macrophages/microglia. J Cell Sci 113(Pt 17):3073–3084

Okie S (2005) Traumatic brain injury in the war zone. N Engl J Med 352:2043–2047. Doi:10.1056/NEJMp058102

Ramlackhansingh AF, Brooks DJ, Greenwood RJ, Bose SK, Turkheimer FE, Kinnunen KM, Gentleman S, Heckemann RA, Gunanayagam K, Gelosa G et al (2011) Inflammation after trauma: microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol 70:374–383. Doi:10.1002/ana.22455

Sajja VS, Tenn C, McLaws LJ, Vandevord PJ (2012) A temporal evaluation of cytokines in rats after blast exposure. Biomed Sci Instrum 48:374–379

Schwulst SJ, Trahanas DM, Saber R, Perlman H (2013) Traumatic brain injury-induced alterations in peripheral immunity. J Trauma Acute Care Surgery 75:780–788. Doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318299616a

Sheng JG, Mrak RE, Griffin WS (1997) Neuritic plaque evolution in Alzheimer's disease is accompanied by transition of activated microglia from primed to enlarged to phagocytic forms. Acta Neuropathol 94:1–5

Smith C, Gentleman SM, Leclercq PD, Murray LS, Griffin WS, Graham DI, Nicoll JA (2013) The neuroinflammatory response in humans after traumatic brain injury. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 39:654–666. Doi:10.1111/nan.12008

Soltys Z, Ziaja M, Pawlinski R, Setkowicz Z, Janeczko K (2001) Morphology of reactive microglia in the injured cerebral cortex. Fractal analysis and complementary quantitative methods J Neurosci Res 63:90–97. Doi:10.1002/1097-4547(20010101)63:1<90::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-9

Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Paulino AJ, Pricop PE, Shaughness MC, Maudlin-Jeronimo E, Hall AA, Janssen WG, Yuk FJ, Dorr NP et al (2013) Blast overpressure induces shear-related injuries in the brain of rats exposed to a mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathologica Commun 1: 51 Doi:10.1186/2051-5960-1-51

Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME (2001) Dynamics of microglial activation: a confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia 33:256–266

Taber KH, Warden DL, Hurley RA (2006) Blast-related traumatic brain injury: what is known? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 18:141–145

Taylor RA, Sansing LH (2013) Microglial responses after ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage. Clin Dev Immunol 2013:746068. Doi:10.1155/2013/746068

Tompkins P, Tesiram Y, Lerner M, Gonzalez LP, Lightfoot S, Rabb CH, Brackett DJ (2013) Brain injury: neuro-inflammation, cognitive deficit, and magnetic resonance imaging in a model of blast induced traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 30:1888–1897. Doi:10.1089/neu.2012.2674

Torres-Platas SG, Comeau S, Rachalski A, Bo GD, Cruceanu C, Turecki G, Giros B, Mechawar N (2014) Morphometric characterization of microglial phenotypes in human cerebral cortex. J Neuroinflammation 11:12 Doi:1742-2094-11-12 [pii] 10.1186/1742-2094-11-12

Valiyaveettil M, Alamneh Y, Oguntayo S, Wei Y, Wang Y, Arun P, Nambiar MP (2012) Regional specific alterations in brain acetylcholinesterase activity after repeated blast exposures in mice. Neurosci Lett 506:141–145

Wang JM, Chen J (2016) Damage of vascular endothelial barrier induced by explosive blast and its clinical significance. Chin J Traumatol 19:125–128

Wang WY, Tan MS, Yu JT, Tan L (2015) Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Transl Med 3:136. Doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.49

Zhou J, Nagarkatti P, Zhong Y, Ginsberg JP, Singh NP, Zhang J, Nagarkatti M (2014) Dysregulation in microRNA expression is associated with alterations in immune functions in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. PLoS One 9:e94075. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094075PONE-D-13-51888

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and independent statistical analyses of the data provided that strengthened considerably the conclusions of this manuscript. The research described here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service Awards 1I01RX000996-01 and I21RX002069. MAGS was supported in part by the General Medical Research Service, James J. Peters VA Medical Center. PRH is supported in part by NIH grant P50 AG005138. RMM, AET and STA were supported in part by work unit number (WUN) 601152 N.0000.000.A1308 from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. PLJ was a Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellow of the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. MAGS, RDG, GMP, GE, AET and STA are employees of the U.S. government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, nor the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAGS, RDG, GPG, FGH, WGJ, PRH and GAE: design of experiments, analysis and interpretation of data, design of neuropathological characterization, stereology, biochemical assays and manuscript writing; HS, CS, DV, PLJ and GMP: execution of neuropathological characterizations and stereology; STA, RMM and AET: design of blast experiments, interpretation of data and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

The article is a work of the United States Government; Title 17 U.S.C 105 provides that copyright protection is not available for any work of the United States government in the United States. Additionally, this is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0), which permits worldwide unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for any lawful purpose.

About this article

Cite this article

Gama Sosa, M.A., De Gasperi, R., Perez Garcia, G.S. et al. Lack of chronic neuroinflammation in the absence of focal hemorrhage in a rat model of low-energy blast-induced TBI. acta neuropathol commun 5, 80 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-017-0483-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-017-0483-z