Abstract

Background

Programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression has been reported in up to 61% of high grade gliomas (HGG). The purpose of this study was to describe safety and efficacy of PD-1 inhibition in patients with refractory HGGs.

Methods

This Institutional Review Board approved single center retrospective study included adult patients with pathologically confirmed HGG who received a PD-1 inhibitor from 9/2014–10/2016 outside of a clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Results

Twenty five HGG patients received pembrolizumab as part of a compassionate use program. Median age was 50 years (range 30–72); 44% were men; 13 had glioblastoma (52%), 7 anaplastic astrocytoma (28%), 2 anaplastic oligodendroglioma (8%), 2 unspecified HGG (8%), and 1 gliosarcoma (4%). Median prior lines of treatments were 4 (range 1–9). Nineteen (76%) previously failed bevacizumab. Median KPS was 80 (range 50–100). Concurrent treatment included bevacizumab in 17 (68%) or bevacizumab and temozolomide in 2 (8%) patients. Median number of doses administered was 3 (range 1–14). Outcomes were assessed in 24 patients. PD-1 inhibitor related adverse events included LFT elevations, hypothyroidism, diarrhea, myalgias/arthralgias, and rash. Best radiographic response was partial response (n = 2), stable disease (n = 5), and progressive disease (n = 17). Median progression free survival (PFS) was 1.4 months (range 0.2–9.4) and median overall survival (OS) was 4 months (range 0.5–13.8). Three-month PFS was 12% and 6-month OS was 28%.

Conclusion

While response rates are low, a few patients had a prolonged PFS. Pembrolizumab was tolerated with few serious toxicities, even in patients receiving concomitant therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High grade malignant gliomas, including anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, anaplastic astrocytoma (grade III) and glioblastomas (grade IV), are the most common primary malignant brain tumors diagnosed in adults [1]. Despite advancements in understanding the underlying pathogenesis, overall survival remains limited with a median survival for glioblastoma, the most aggressive high grade glioma (HGG), between 16 and 19 months [1]. Upfront therapy for glioblastoma consists of maximal safe resection followed by radiation with concurrent temozolomide and adjuvant temozolomide [2]. Median survival for patients with recurrent grade III and grade IV tumors is 39 and 30 weeks, respectively [3]. Progression free survival at 26 weeks is 28% for grade III tumors and 16% for grade IV tumors. Non-surgical treatment options for recurrent or progressive high grade gliomas are limited. FDA approved treatment options for recurrent glioblastoma include an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agent, bevacizumab, and low-intensity alternating electric fields (TTFields); neither treatment has been shown to significantly improve overall survival [4,5,6]. Other treatment options include conventional chemotherapy such as temozolomide in different dosing schedules, carboplatin, irinotecan, and nitrosoureas [7].

Checkpoint inhibitors have advanced treatment for metastatic melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and other malignancies [8, 9]. For patients diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer, the level of programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression has been associated with improved outcomes to PD-1 inhibitors [8, 10, 11]. The presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and PD-L1 expression has been reported in up to 61% of high grade gliomas and therefore this checkpoint is a viable target for treatment [12, 13]. PD-1 inhibitors block the interaction between PD-L1 and its receptor thereby overcoming T-cell inhibition and promoting an immune response against the tumor. Developing effective treatment options for malignant high grade gliomas has proven difficult due to the inability of many medications to cross the blood brain barrier. Data evaluating the penetration of checkpoint inhibitors across the blood brain barrier is limited. However, the activity of immunotherapy for brain metastasis from melanoma and lung cancer has been reported and is promising [14]. Additionally, there have been case reports of prolonged response after checkpoint inhibitors in patients with glioblastoma [15, 16]. Currently, there are an abundance of clinical trials evaluating checkpoint inhibitors of patients with glioblastoma. Unfortunately, many patients with high grade gliomas are excluded due to previous treatments, performance status, or tumor histology [12, 17, 18]. At our institution, many patients with high grade gliomas that do not qualify for clinical trial receive off label checkpoint inhibitors. The purpose of this retrospective study is to describe efficacy and safety of PD-1 inhibitors in patients with refractory malignant high grade gliomas.

Methods

Study design

This was an Institutional Review Board approved single-center observational retrospective study performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center evaluating patients with pathology confirmed high grade malignant glioma who received a PD-1 inhibitor outside of a clinical trial. Patients were identified through the pharmacy database and electronic medical records. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients who were 18 years of age or older and had received a PD-1 inhibitor between September 2014 and October 2016. Patients were excluded if they received a PD-1 inhibitor as part of a clinical trial.

Endpoints and assessments

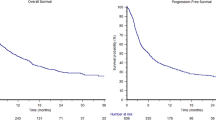

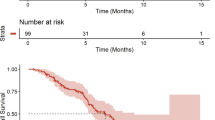

The primary objective of this study was to describe overall response rate (ORR) on contrast enhanced MRI. Secondary objectives included characterizing toxicities according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03 as well as describing progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables and medians and ranges were used to describe continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to visualize PFS and OS; patients were censored at the last follow up date if an event did not occur.

Results

Patient characteristics

Twenty-nine neuro-oncology patients received a PD-1 inhibitor between September 2014 and October 2016. Four patients were excluded; 3 patients received previous checkpoint inhibitor therapy as part of a clinical trial and 1 patient did not have a high grade glioma. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The median age was 49 years (range: 30–72 years), 11 patients were male (44%), and the majority of patients were Caucasian (88%). All patients received pembrolizumab as PD-1 inhibitor for treatment of HGG through a compassionate use program. Thirteen patients had pathology confirmed glioblastoma (52%), 7 anaplastic astrocytoma (28%), 2 anaplastic oligodendroglioma (8%), 2 unspecified HGG (8%), and 1 gliosarcoma (4%). Four patients (16%) were MGMT methylated, 12 (48%) were MGMT unmethylated and 9 (36%) were unknown. Ten patients (40%) had tumors that harbored an IDH1 mutation, 9 (36%) were IDH1 wild type, and 6 (24%) were unknown. Median mutational load was 7 with a range of 3–58 (Table 2). None of the patients were considered to have a hypermutator phenotype, defined as 100 or more mutations, by MSK-Impact.16 Patients were heavily pretreated, receiving a median of 4 prior lines of therapy (range 1–9) and 19 patients (76%) previously progressed on bevacizumab treatment. Median KPS at initiation of pembrolizumab was 80 (range 50–100). Concurrent treatment with pembrolizumab included bevacizumab in 17 (68%) or bevacizumab and temozolomide in 2 (8%) patients. Out of the 19 patients who previously failed bevacizumab, 17 continued on bevacizumab with pembrolizumab therapy. Of the six patients who did not previously receive bevacizumab therapy, two were started on bevacizumab in combination with pembrolizumab. Median number of doses of pembrolizumab administered was 3 (range 1–14). Fourteen patients (56%) were on dexamethasone during their first treatment dose and 19 patients (79%) received dexamethasone at some point during the course of treatment with pembrolizumab. Out of the 105 total doses of pembrolizumab administered, 34 doses (32%) were administered with concomitant dexamethasone for treatment of disease related neurologic symptoms.

Efficacy

Treatment response and toxicity was evaluable in 24 patients. One patient was excluded from evaluation of response and toxicity because they transitioned to hospice less than one week after their first and only dose of pembrolizumab; therefore, imaging and toxicity data is not available. This patient was included in survival analysis. Best radiographic response was partial response (n = 2, 8%), stable disease (n = 5, 21%), and progressive disease (n = 17, 71%) (Table 3). Both of the patients with a partial response received concomitant bevacizumab, and one patient was bevacizumab-naïve. These two patients received pembrolizumab plus bevacizumab in the second and third line setting for treatment of glioblastoma and anaplastic astrocytoma, respectively. Both patients received dexamethasone for management of disease related symptoms, one at initiation of pembrolizumab treatment. Duration of therapy, best radiographic response, previous bevacizumab, and concomitant bevacizumab can be visualized in Figs. 1 and 2. Two patients had stable disease greater than 200 days. One of these patients received bevacizumab plus pembrolizumab after failing 9 prior treatments including bevacizumab containing regimens. The other patient received pembrolizumab monotherapy after failing 2 prior lines of therapy. The first patient was on dexamethasone only during their first dose of pembrolizumab. The second patient did not receive dexamethasone during treatment with pembrolizumab. Of note, 7 of the 18 patients without a clinical response did not require steroids at treatment initiation. The median mutation load was 6 in patients with partial response and stable disease compared to 7 in those who did not respond. Median progression free survival (PFS) was 1.4 months (range 0.2–9.4) and median overall survival (OS) was 4 months (range 0.5–13.8) (Fig. 3). Six month PFS was 12% and 6 month OS was 28%.

Best Radiographic Response in Grade III Glioma Patients. BEV = bevacizumab. The X axis represents the number of doses of pembrolizumab that was received. The color represents the best radiographic response each patient had. 3 patients continue on pembrolizumab at the end of data collection. 6 patients previously progressed on bevacizumab; of those patients 5 continued bevacizumab with pembrolizumab. 4 patients never received bevacizumab, of those 1 started on bevacizumab with pembrolziumab. One patient had a partial response; 2 had stable disease; and the rest had progressive disease

Best Radiographic Response in Grade IV Glioma Patients. BEV = bevacizumab. The X axis represents the number of doses of pembrolizumab that was received by each patient. The color represents the best radiographic response each patient had. One patient continue on pembrolizumab at the end of data collection. Eleven patients previously progressed on bevacizumab; of those patients 10 continued bevacizumab with pembrolizumab. 2 patients never received bevacizumab and, of those, one started on bevacizumab with pembrolziumab. One patient had a partial response; 3 had stable disease; and the rest had progressive disease

Toxicity

All toxicities are listed in Table 4. The most common adverse events reported were fatigue (grade 3–4: 4%; grade 1–2: 75%), headache (grade 3–4: 4%; grade 1–2: 43%), nausea (grade 3–4: 4%; grade 1–2: 37.5%), diarrhea (grade 3–4: 0%; grade 1–2: 17%), seizures (grade 3–4: 4%; grade 1–2: 17%), vomiting (grade 3–4: 4%; grade 1–2: 17%), myalgias/arthralgia (grade 3–4: 0%; grade 1–2: 13%), and rash (grade 3–4: 0%; grade 1–2: 8%). The most common laboratory abnormalities recorded were hyperglycemia (grade 1–2: 79%), thrombocytopenia (grade 1–2: 50%), leukopenia (grade 1–2: 37.5%), ALT elevations (grade 1–2: 33%), AST elevations (grade 1–2: 29%), bilirubin elevations (grade 1–2: 21%), neutropenia (grade 1–2: 21%), and hypothyroidism (grade 1–2: 17%). Additionally, 74% of patients (n = 14) who experienced hyperglycemia were receiving dexamethasone. One patient with a history of epilepsy was admitted for a grade 3 seizure. The second patient who experienced grade 3 adverse events, specifically nausea, vomiting, and headache, was admitted for symptoms of increased intracranial pressure due to pathology confirmed recurrent glioblastoma. Lastly, one patient experienced grade 4 cerebral edema requiring emergent surgery 7 days after their first and only dose of pembrolizumab. Pathology confirmed edema was due to rapid tumor progression. No patients discontinued pembrolizumab due to toxicity.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that heavily pretreated patients with malignant high grade gliomas have low response rates to pembrolizumab. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate PD-1 inhibition in grade III gliomas. Garber and colleagues found that PD-L1 expression was only present on grade IV gliomas, where as it was not present in the 33 anaplastic astrocytomas or 9 oligodendrogliomas. [19] There is no current data correlating PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes outside of pembrolizumab use in non-small cell lung cancer. In our grade III glioma cohort, 1 patient had a partial response to pembrolizumab and 2 patients had prolonged progression free survival with pembrolizumab.

Pembrolizumab monotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma was studied in the KEYNOTE-028 trial. [20] Patients were included if they were diagnosed with glioblastoma having PD-L1 expression ≥1%, bevacizumab naïve, and unable to receive standard treatment. Median PFS and OS were reported as 2.8 months and 14.4 months, respectively. CheckMate-143 compared nivolumab monotherapy to bevacizumab monotherapy in glioblastoma in patients with first recurrence. Median OS was 9.8 months with nivolumab and 10 months with bevacizumab, PFS was 1.5 months with nivolumab and 3.5 months with bevacizumab, demonstrating no improvement in overall survival. [21] We observed a shorter PFS and OS most likely because patients that failed bevacizumab were also included.

Pembrolizumab was well tolerated in our cohort; toxicities were similar compared to those reported with other malignancies. [8, 9] Very few serious adverse events occurred during treatment. Serious adverse events, cerebral edema, seizures and headaches could be related to disease progression or checkpoint inhibition.

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective study with a small sample size. Second, many patients received pembrolizumab in combination with other treatment modalities such as bevacizumab, making it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of pembrolizumab monotherapy in high grade glioma patients. Additionally, we included patients with both WHO grade III and IV gliomas, making it difficult to compare these results to published data that includes only glioblastoma patients. Many of our patients were excluded from participation in clinical trials for checkpoint inhibitors due to their WHO grade, previous treatment with bevacizumab, and poor KPS. This patient population differs from previously reported clinical observations using checkpoint inhibitors as it includes grade III and IV gliomas. The observed response rate and survival data might be biased due to the poor prognostics factors in our population (heavily pretreated, bevacizumab-resistance, low KPS performance status). However, these patients are frequently encountered in the clinical setting with little literature to guide treatment decisions.

We also did not account for baseline abnormalities and due to the retrospective nature of this study were unable to differentiate between treatment related toxicity and disease related adverse events. Lastly, we did not assess PD-L1 expression to correlate clinical response to PD-L1 status. Pembrolizumab requires further studies to confirm a benefit for patients with refractory high grade glioma as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy or bevacizumab.

Conclusions

Patients with pathology confirmed refractory high grade gliomas have low response rates to pembrolizumab. However, a small number of patients have a prolonged progression free survival. Pembrolizumab was tolerated with few serious adverse events, even in patients receiving concomitant therapy. Pembrolizumab requires further study to confirm a benefit for patients with refractory high grade glioma as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy or bevacizumab.

Abbreviations

- Bev:

-

Bevacizumab

- co-del:

-

1p19q codeleted

- Con Bev:

-

Concomitant bevacizumab

- CR:

-

Complete response

- CTCAE:

-

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- HGG:

-

high grade gliomas

- intact:

-

1p19q intact

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky performance score

- methylated:

-

MGMT methylated

- ML:

-

mutational load by MSK impact

- MUT:

-

IDH mutant

- N:

-

no

- N/A:

-

not applicable or unknown

- OR:

-

Objective response

- ORR:

-

Overall response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD:

-

progressive disease

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death ligand-1

- Pembro:

-

pembrolizumab

- PFS:

-

Progression free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- Prev Bev:

-

previously progressed on bevacizumab treatment

- Pt:

-

Patient

- SD:

-

stable disease

- unmethylated:

-

MGMT unmethylated

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT:

-

IDH wild type

- Y:

-

yes

References

Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507.

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96.

Lamborn KR, Yung WK, Chang SM, Wen PY, Cloughesy TF, DeAngelis LM, Robins HI, Lieberman FS, Fine HA, Fink KL, et al. Progression-free survival: an important end point in evaluating therapy for recurrent high-grade gliomas. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10:162–70.

Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, Steinberg D, Engelhard H, Heidecke V, Kirson ED, Taillibert S, Liebermann F, Dbaly V, et al. NovoTTF-100A versus physician's choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2192–202.

Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, Yung WK, Paleologos N, Nicholas MK, Jensen R, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–40.

AVASTIN (bevacizumab) [package insert]. Genentech, Inc, San Francisco, CA; 2016. [https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/avastin_prescribing.pdf].

Chamberlain MC. Salvage therapy with lomustine for temozolomide refractory recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma: a retrospective study. J Neuro-Oncol. 2015;122:329–38.

KEYTRUDA (pembrolizumab) [package insert]. Merck & Co., Inc. Whitehouse Station, NJ; 2016. [http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/k/keytruda/keytruda_pi.pdf].

OPDIVO (nivolumab) [package insert]. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ; 2017. [http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_opdivo.pdf].

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–33.

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54.

Berghoff AS, Kiesel B, Widhalm G, Rajky O, Ricken G, Wohrer A, Dieckmann K, Filipits M, Brandstetter A, Weller M, et al. Programmed death ligand 1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:1064–75.

Nduom EK, Wei J, Yaghi NK, Huang N, Kong LY, Gabrusiewicz K, Ling X, Zhou S, Ivan C, Chen JQ, et al. PD-L1 expression and prognostic impact in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2016;18:195–205.

Goldberg SB, Gettinger SN, Mahajan A, Chiang AC, Herbst RS, Sznol M, Tsiouris AJ, Cohen J, Vortmeyer A, Jilaveanu L, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:976–83.

Roth P, Valavanis A, Weller M. Long-term control and partial remission after initial pseudoprogression of glioblastoma by anti-PD-1 treatment with nivolumab. Neuro-Oncology. 2016;

Bouffet E, Larouche V, Campbell BB, Merico D, de Borja R, Aronson M, Durno C, Krueger J, Cabric V, Ramaswamy V, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition for Hypermutant glioblastoma Multiforme resulting from germline Biallelic mismatch repair deficiency. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2206–11.

Reardon DA, DeGroot JF, Colman H, Jordan JT, Daras M, Clarke JL, Nghiemphu PL, Gaffey SC, Peters KB. Safety of pembrolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34

Ampie L, Woolf EC, Dardis C. Immunotherapeutic advancements for glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:12.

Garber ST, Hashimoto Y, Weathers SP, Xiu J, Gatalica Z, Verhaak RG, Zhou S, Fuller GN, Khasraw M, de Groot J, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade as a potential therapeutic target: surveying CNS malignancies. Neuro-Oncology. 2016;18:1357–66.

TM RDAK, Frenel JS, Santoro A, et al. ATIM-35. Results of the Phase IB KEYNOTE-028 Multi-Cohort Trial of Pembrolizumab Monotherapy in Patietns with Recurrent PD-L1 Positive Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:vi25–6.

Reardon DA, Omuro A, Brandes AA, et al. Randomized phase 3 study evaluating the efficacy and safety of Nivolumab vs bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: CheckMate 143. Neuro-Oncology. 2017;19:iii21. https://academic.oup.com/neuro-oncology/article/19/suppl_3/iii21/3743874#.

Acknowledgements

not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support/Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Availability of data and materials

N/A

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SNR participated in conceiving the study, obtaining data, interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript; PY participated in obtaining data and reviewing the manuscript; LM participated in obtaining data and reviewing the manuscript; CG participated in conceiving the study, performing statistical analysis, interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Reiss, S.N., Yerram, P., Modelevsky, L. et al. Retrospective review of safety and efficacy of programmed cell death-1 inhibitors in refractory high grade gliomas. j. immunotherapy cancer 5, 99 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-017-0302-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-017-0302-x