Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is associated with significant increases in short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Drug-induced AKI is a major concern in the present healthcare system. Our spontaneous reporting system (SRS) analysis assessed links between AKI, along with patients’ age, as healthcare-associated risks and administered anti-infectives. We also generated anti-infective-related AKI-onset profiles.

Method

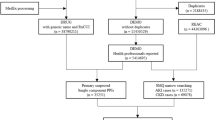

We calculated reporting odds ratios (RORs) for reports of anti-infective-related AKI (per Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) in the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database and evaluated the effect of anti-infective combination therapy. The background factors of cases with anti-infective monotherapy and combination therapy (≥ 2 anti-infectives) were matched using propensity score. We evaluated time-to-onset data and hazard types using the Weibull parameter.

Results

Among 534,688 reports (submission period: April 2004–June 2018), there were 21,727 AKI events. The reported number of AKI associated with glycopeptide antibacterials, fluoroquinolones, third-generation cephalosporins, triazole derivatives, and carbapenems were 596, 494, 341, 315, and 313, respectively. Crude RORs of anti-infective-related AKI increased among older patients and were higher in anti-infective combination therapies [anti-infectives, ≥ 2; ROR, 1.94 (1.80–2.09)] than in monotherapies [ROR, 1.29 (1.22–1.36)]. After propensity score matching, the adjusted RORs of anti-infective monotherapy and combination therapy (≥ 2 anti-infectives) were 0.67 (0.58–0.77) and 1.49 (1.29–1.71), respectively. Moreover, 48.1% of AKI occurred within 5 days (median, 5.0 days) of anti-infective therapy initiation.

Conclusion

RORs derived from our new SRS analysis indicate potential AKI risks and number of administered anti-infectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is associated with significant increase in short- and long-term morbidity and mortality [1] and occurs in approximately 1–5% of all patients treated at the hospital [2]. AKI is a sudden episode of kidney failure or kidney damage that happens within a few hours or a few days [1, 3]. Drug-induced AKI has been implicated in 8 to 60% of all cases of in-hospital AKI and as such is a recognized source of significant morbidity and mortality [4]. Healthcare professionals should be aware of potential AKI risk since occasional fatalities have also been observed. Thus, drug-induced AKI is a major concern in the present healthcare system. AKI is pre-renally caused by cardiovascular disorders and hypovolemia, intra-renally caused by acute tubular necrosis and other parenchymal disorders, or post-renally caused by bladder obstruction and ureteral obstruction [2, 4, 5]. Several antibiotics including penicillin analogs, cephalosporins, and ciprofloxacin are known to increase the risk of intra-renal AKI [5], and other antibiotics such as aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, and vancomycin have been identified as the cause of adverse events (AEs) in AKI [4].

Spontaneous reporting systems (SRSs), such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) adverse event reporting system (FAERS) and the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) database, have been used in pharmacovigilance assessments [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. The reporting odds ratio (ROR) has been used to derive an index for detecting drug-associated adverse events (AEs) [13, 14]. A previous study using the FAERS demonstrated that vancomycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, piperacillin–tazobactam, and ciprofloxacin have significant reporting associations with AKI [6]; however, the study did not include less frequently used colistin and aminoglycosides and their association with AKI. Patek et al. conducted a more detailed study focused on anti-infectives using the FAERS database [7]. It has been reported that piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin were frequently reported to be associated with AKI using the JADER database [8]. However, the detailed time-to-onset profiles of antibiotics was not established clearly in SRSs; therefore, we focused on this aspect in our present study.

Polypharmacy is a well-known risk factor for AEs. Altered liver and kidney functions are considered a cause for changes in the pharmacokinetics in elderly patients [15]. Older patients often suffer from multiple diseases and receive several drugs, which is referred to as polypharmacy [16,17,18]. Pierson-Marchandise et al. suggested that AKI risk is particularly high corresponding to polypharmacy, and increases proportionate to the number of drugs administered [19]. We previously analyzed an SRS database and found that the combination of medications might increase the risk of AEs according to the index derived from the RORs [10, 11]. Using a multivariate logistic regression analysis technique, Abe et al. showed that the number of drugs administered and age might be more closely linked to an increased risk of kidney disorder than liver disorder [10]. Recently, propensity score (PS) matching has been used as an assessment approach to reduce selection bias by equating groups based on covariates or other appropriate parameters [20]. Its usefulness has been evident from the analysis of AE reports in the FAERS database [9]. In this study, we evaluated the anti-infective-related AKI profiles using ROR, the time-to-onset data of AKI with respect to anti-infective therapy initiation, and the effect of the number of anti-infectives administered in a clinical setting using real-world data.

Methods

The JADER dataset is publicly available and can be downloaded from the website of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) (www.pmda.go.jp). This study used a dataset containing information recorded between April 2004 and June 2018. The JADER database consists of four tables: patients’ demographic information (DEMO), drug information (DRUG), AE information (REAC), and primary disease information (HIST). The four data tables imported to the relational database (FileMaker Pro 14 software (FileMaker, Santa Clara, CA, USA)). The “DRUG” table contains the role code assigned to each drug: “suspected drug,” “concomitant drug,” and “interacting drug.” All drugs in the “suspected drug,” “concomitant drug,” and “interacting drug” association classes were used for the analyses.

The AEs in the JADER database are coded according to the preferred terminology by the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities/Japanese (MedDRA/J) version 19.0 (MedDRA/J, www.pmrj.jp/jmo/php/indexj.php). The MedDRA dictionary is organized with a five-level hierarchy, including System Organ Class (SOC), High-Level Group Terms (HLGT), High-Level Terms (HLT), Preferred Terms (PT), and Lowest Level Terms (LLT). Preferred Terms (PTs) represent more precise medical terminology. Several studies on AKI have been reported; however, we could not find a standard criterion for the selection of PTs in each category. Patek et al. and Hosohata et al. selected a PT of “acute kidney injury” in a study on AKI [7, 8]. Welch et al. used 22 search terms based on AKI expert opinion [6]. Standardized MedDRA Queries (SMQ) are groupings of MedDRA terms, ordinarily PTs, that relate to a defined medical condition [21]. Pierson-Marchandise et al. selected 44 PTs according to SMQ (code: 20000003) [19]. Selection of a large number of PTs such as SMQ generally allows identification of all possible cases inclusive of less-specific cases. Selection of small number of PTs allows identification of cases that precisely define the condition of interest. We selected 19 PTs to extract case reports of AKI-related AEs based on SMQ and previous reports (Table 1). To identify an AE signal, we calculated crude ROR by using a two-by-two contingency table [14, 22]. The RORs indicated the presence or absence of a particular drug and a particular AE in the database, and were expressed as point estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The signal of a drug-AE combination was considered statistically significant when the estimated ROR and lower limit of the corresponding 95% CI was greater than one. The positive identification of a signal required two or more cases [14, 22].

The propensity score (PS) matching is a statistical matching technique to construct matched sets with similar distributions of the covariates, without requiring close or exact matches on all of the individual variables [20]. The following variables were included in the multiple logistic regression model: age, body weight, height, sepsis, and number of anti-infectives administered. The presence or absence of AKI was evaluated as the outcome. Patients with sepsis related terms input to “REAC” and “HIST” tables were considered to have a sepsis background (Table 2). Data was not arranged according to the severity of the disease because it was not included in the case reports extracted from the JADER database. Nearest neighbor matching was performed based on the calculated PS between anti-infective monotherapy and combination therapy (≥ 2 anti-infectives). A caliper width of 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of PS was used. The standard mean difference (SMD) was used as a covariate balance indicator between anti-infective monotherapy and combination therapy. The SMD values below 0.1 were considered optimal for an adequate covariate balance.

To assess the time-to-onset profile, the median time from the first prescription of each report to the onset of AKI was used in conjunction with the interquartile range and Weibull shape parameter (WSP) [12, 23]. We selected an analysis period of 90 days after therapy initiation. The rate of occurrence of AEs after prescription is thought to depend on the causal mechanism. The WSP represents the failure rate distribution against time. A larger scale value (α) of the Weibull distribution indicates a wider data distribution. A smaller scale value (α) shrinks the data distribution. The WSP (β) has been used to determine the level of hazard over time without a reference population. When β is equal to 1, the hazard is considered to be constant over time. When β was lower than 1, the hazard was considered to decrease over time (initial failure type). In contrast, when β was greater than 1, the hazard was considered to increase over time (wear-out failure type) [23]. The results obtained from the WSP are complementary to the results of the disproportionality analysis using ROR.

These data analyses were performed using JMP Pro 16.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The JADER database contains 534,688 reports submitted between April 2004 and June 2018, and we identified 21,727 AKI events. According to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System (www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/), 145 anti-infectives were selected and categorized into 36 ATC-drug classes (S1 Table).

In the top five anti-infective therapies, glycopeptide antibacterials (ATC code: J01XA), fluoroquinolones (ATC code: J01MA), third-generation cephalosporins (ATC code: J01DD), triazole derivatives (ATC code: J02AC), and carbapenems (ATC code: J01DH), we identified 596, 494, 341, 315, and 313 reported AKI-associated AEs, respectively (Table 3). The lower limit of the 95% CI (confidence interval) of ROR was > 1 for the following drug groups: combinations of penicillins, including beta-lactamase inhibitors (ATC code: J01CR), second-generation cephalosporins (ATC code: J01DC), third-generation cephalosporins (ATC code: J01DD), fourth-generation cephalosporins (ATC code: J01DE), monobactams (ATC code: J01DF), carbapenems (ATC code: J01DH), intermediate-acting sulfonamides (ATC code: J01EC), combinations of sulfonamides and trimethoprim, including derivatives (ATC code: J01EE), lincosamides (ATC code: J01FF), other aminoglycosides (ATC code: J01GB), fluoroquinolones (ATC code: J01MA), other quinolones (ATC code: J01MB), glycopeptide antibacterials (ATC code: J01XA), polymyxins (ATC code: J01XB), other antibacterials (ATC code: J01XX), antibiotics (ATC code: J02AA), triazole derivatives (ATC code: J02AC), and other antimycotics for systemic use (ATC code: J02AX).

AKI crude RORs (95% CI) for vancomycin, tazobactam/piperacillin, and vancomycin plus tazobactam/piperacillin were 4.00 (3.69–4.33), 3.48 (3.16–3.83), and 6.07 (4.96–7.43), respectively (Table 4). The crude RORs (95% CI) of age (80–89, and ≥ 90 years), and the number of anti-infectives administered (1 and ≥ 2) were 1.58 (1.52–1.64), 1.89 (1.74–2.06), 1.29 (1.22–1.36), and 1.94 (1.80–2.09), respectively (Table 5). The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the PS determine the accuracy of the model predictions of treatment allocation. The area under the ROC curve was 0.5766 (data not shown). Since the SMD of each factor was below 0.1, the background factors of cases with anti-infective monotherapy and ≥ 2 anti-infectives were matched (Table 6). After the PS matching, the adjusted RORs of anti-infective monotherapy and combination therapy (≥ 2 anti-infectives) were 0.67 (0.58–0.77) and 1.49 (1.29–1.71), respectively.

Combinations containing the complete information on the treatment start date and AE onset date were extracted for the time-to-onset analysis. We evaluated 14 anti-infective categories for which the number of cases was more than 100 and the lower limit of the 95% CI exceeded 1 as shown in Table 3 (Table 7, S1 Figure). S1 Figure shows a histogram of the number of AKI onsets in relation to the number of days after anti-infective treatment initiation (from day 0 to day 90). The median period (interquartile range) until AKI onset caused by anti-infectives was 5.0 (2.0–11.0) days for orally (per os, po) administered anti-infectives and 5.0 (2.0–9.0) days for administration by intravenous (iv) injection. The upper limits of the 95% CI of the β value were less than 1 for po administered anti-infectives.

Discussion

AKI is a complication in clinical care that can be linked to a variety of anti-infectives. Signals indicating an association with AKI were detected in many categories of anti-infectives (Table 3). Polymyxins (ATC code: J01XB) had the highest crude ROR among 36 ATC-drug classes of anti-infectives (Table 3). The detailed mechanism of AKI by polymyxin remains unclear [24]. In our study, 106 out of 107 reports on polymyxin-related AKI indicated colistin (ATC code: J01XB01) administration, which was associated with an AKI incidence rate of approximately 10 to 55% [25]; the finding is consistent with as reported by Patek et al. that colistin had the highest AKI ROR in the FAERS database [7]. ROR signals were also associated with other anti-infectives. Aminoglycosides cause tubular cell toxicity, and vancomycin is linked to acute interstitial nephritis [25]. The incidence rate of nephrotoxicity is reportedly up to 58% in patients treated with aminoglycosides, but most recent reviews suggest rates of 5 to 15% [4]. All AKI reports in antimycotics were from amphotericin B. Amphotericin B causes AKI when used as monotherapy or combination therapy [4] and raises blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine in 80% of patients receiving a complete course of amphotericin B therapy [26].

The crude ROR values indicated the occurrence of AKI in anti-infectives-treated patients in the age ranges of 70–79 years, 80–89 years, and ≥ 90 years and in patients receiving anti-infective monotherapy or combination treatment (≥ 2 anti-infectives) (Table 5). However, the crude ROR is insufficient for assessing the relative strength of causality between drugs and AEs and only provides an approximation of the signal strength [14, 22].

The adjusted RORs after PS matching were used to make adjustments by multivariate logistic regression analyses, which mitigated the effects of covariates. The adjusted RORs tended to be higher in anti-infective combination therapy than in monotherapy. These results strongly suggested that the number of anti-infectives administered are related to the occurrence of AKI. A meta-analysis demonstrated that vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam combination therapy had higher odds of AKI than vancomycin monotherapy, piperacillin–tazobactam monotherapy, and vancomycin plus cefepime or carbapenem combination therapy; the findings are suggestive of drug-drug interactions leading to AKI [7, 27]. We also observed higher AKI crude ROR of vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam combination therapy than that of vancomycin monotherapy and piperacillin–tazobactam monotherapy. Since vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam are common empiric antibiotic combinations, these findings have important implications in antimicrobial administration.

Aging is known to decrease renal drug elimination [28], which is associated with an increased risk of AKI by high drug exposure in the elderly. Rybak et al. reported AKI incidence rates of 5, 11, and 22% in patients treated with vancomycin monotherapy, aminoglycoside monotherapy, and combination therapy consisting of vancomycin and one aminoglycoside, respectively [29]. Thus, anti-infective combination therapy may increase the risk of AKI in older patients, which should be considered more carefully in clinical practice.

The time-to-onset analysis derived the daily numbers of onset events. We found that 48.1% of anti-infective-related AKI occurred within 5 days of treatment initiation, and the median for anti-infective-related AKI onset was 5.0 days post-initiation (Table 7, S1 Figure). We did not detect statistically significant differences of time-to-onset profiles among the different types of anti-infectives (14 ATC-drug classes) or the route of administration (iv versus po). The finding that there is no significant difference in AKI time-to-onset profile with respect to dosage forms (iv versus po) is interesting and warrants future studies for its validation.

There are inherent limitations in using SRS data. For example, the length of the post-launch period of the drug, the notification of AEs, missing data, over-reporting of AKI associated with antimicrobials, especially in the elderly, and under-reporting affect SRS analysis. There was no suitable comparison group, and data on patient characteristics were incomplete. The results of anti-infective combination therapy were partially refined using the PS matching technique. Therefore, adjusted RORs are likely to have improved odds accuracy compared to that of crude RORs.

It has been reported that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine, tacrolimus), sulfonamides, acyclovir, rifampin, phenytoin, interferon, and proton pump inhibitors are involved in AKI [5]. In this study, we did not evaluate the effect of concomitant drugs other than anti-infectives. More reliable epidemiological studies will be needed to derive the causal constraints from this analysis.

Conclusions

The JADER database, which includes clinicians’ reports of potential AE concerns related to drugs, is a useful tool for pharmacovigilance because it is based on real-world data derived from clinical practice. We used adjusted RORs after PS matching to identify the risk of anti-infective-related AKI linked to the number of anti-infectives administered. We observed higher AKI crude ROR of vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam combination therapy than that of vancomycin monotherapy and piperacillin–tazobactam monotherapy. The median period of anti-infective-related AKI onset was 5 days after therapy initiation. We believe that our data will provide guidance for reducing the incidence of AEs in elderly patients receiving polypharmacy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- SRS:

-

Spontaneous reporting systems

- JADER:

-

Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report

- PMDA:

-

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency

- MedDRA:

-

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

- WSP:

-

Weibull shape parameter

References

Moore PK, Hsu RK, Liu KD. Management of acute kidney injury: core curriculum 2018. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(1):136–48. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.021.

Patschan D, Muller GA. Acute kidney injury. J Inj Violence Res. 2015;7(1):19–26. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v7i1.604.

KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes). Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. 2012. Available from: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/KDIGO-2012-AKI-Guideline-English.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2020.

Khalili H, Bairami S, Kargar M. Antibiotics induced acute kidney injury: incidence, risk factors, onset time and outcome. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51(12):871–8.

Rahman M, Shad F, Smith MC. Acute kidney injury: a guide to diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(7):631–9.

Welch HK, Kellum JA, Kane-Gill SL. Drug-associated acute kidney injury identified in the United States Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system database. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(8):785–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2152.

Patek TM, Teng C, Kennedy KE, Alvarez CA, Frei CR. Comparing acute kidney injury reports among antibiotics: a pharmacovigilance study of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Drug Saf. 2020;43(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-019-00873-8.

Hosohata K, Inada A, Oyama S, Furushima D, Yamada H, Iwanaga K. Surveillance of drugs that most frequently induce acute kidney injury: a pharmacovigilance approach. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(1):49–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12748.

Akimoto H, Oshima S, Negishi A, Ohara K, Ohshima S, Inoue N, et al. Assessment of the risk of suicide-related events induced by concomitant use of antidepressants in cases of smoking cessation treatment with varenicline and assessment of latent risk by the use of varenicline. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163583.

Abe J, Umetsu R, Uranishi H, Suzuki H, Nishibata Y, Kato Y, et al. Analysis of polypharmacy effects in older patients using Japanese adverse drug event report database. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0190102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190102.

Kato Y, Umetsu R, Abe J, Ueda N, Nakayama Y, Kinosada Y, et al. Hyperglycemic adverse events following antipsychotic drug administration in spontaneous adverse event reports. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2015;1(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-015-0015-6.

Hasegawa S, Ikesue H, Nakao S, Shimada K, Mukai R, Tanaka M, et al. Analysis of immune-related adverse events caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors using the Japanese adverse drug event report database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29(10):1279–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5108.

van Puijenbroek EP, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER, Leufkens HG. Detecting drug-drug interactions using a database for spontaneous adverse drug reactions: an example with diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56(9–10):733–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002280000215.

Poluzzi E, Raschi E, Piccinni C, Ponti FD. Data mining techniques in pharmacovigilance: analysis of the publicly accessible FDA adverse event reporting system (AERS). Intech. 2012. https://doi.org/10.5772/50095. Accessed 2 July 2020.

ElDesoky ES. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic crisis in the elderly. Am J Ther. 2007;14(5):488–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mjt.0000183719.84390.4d.

Washington, DC: US Goverment Printing Office. Federal interagency forum on aging-related statistics. Older Americans Update 2006: Key indicators of well-being. Available from: https://agingstats.gov/docs/PastReports/2006/OA2006.pdf Accessed 2 July 2020.

Gurwitz JH. Polypharmacy: a new paradigm for quality drug therapy in the elderly? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(18):1957–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.18.1957.

Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):345–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.002.

Pierson-Marchandise M, Gras V, Moragny J, Micallef J, Gaboriau L, Picard S, et al. The drugs that mostly frequently induce acute kidney injury: a case-noncase study of a pharmacovigilance database. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(6):1341–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13216.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41.

MedDRA MSSO. Introductory guide for Standardised MedDRA Queries (SMQs) version 19.0. 2016. Available at: http://www.meddra.org/sites/default/files/guidance/file/smq_intguide_19_0_english.pdf.

van Puijenbroek EP, Bate A, Leufkens HG, Lindquist M, Orre R, Egberts AC. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.668.

Sauzet O, Carvajal A, Escudero A, Molokhia M, Cornelius VR. Illustration of the weibull shape parameter signal detection tool using electronic healthcare record data. Drug Saf. 2013;36(10):995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0061-7.

Sirijatuphat R, Limmahakhun S, Sirivatanauksorn V, Nation RL, Li J, Thamlikitkul V. Preliminary clinical study of the effect of ascorbic acid on colistin-associated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(6):3224–32. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00280-15.

Naughton CA. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(6):743–50.

Laniado-Laborín R, Cabrales-Vargas MN. Amphotericin B: side effects and toxicity. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2009;26(4):223–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riam.2009.06.003.

Luther MK, Timbrook TT, Caffrey AR, Dosa D, Lodise TP, LaPlante KL. Vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam and acute kidney injury in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(1):12–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002769.

Weinstein JR, Anderson S. The aging kidney: physiological changes. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(4):302–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2010.05.002.

Rybak MJ, Albrecht LM, Boike SC, Chandrasekar PH. Nephrotoxicity of vancomycin, alone and with an aminoglycoside. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25(4):679–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/25.4.679.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number, 17 K08452, 20 K10408, and 21 K06646). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish this article, or its preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to this scientific work and approved the final version of the manuscript. SN, SH, and MN designed this study, performed the data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. RU, and YN involved in methodology and software. KS, RM, MT, KM, YY, MI, and RS assisted the data curation and validation. JL supervised the drafting of the manuscript. All authors took responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Our research does not fall within the purview of any of the following laws and guidelines: “Clinical Trials Act (Act No. 16 of April 14, 2017),” “Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products Including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law number: Act No. 145 of 1960, Last Version: Amendment of Act No. 50 of 2015),” “Guideline for good clinical practice E6 (R1), https://www.pmda.go.jp/int-activities/int-harmony/ich/0076.html,” “Ethical guidelines for human genome and gene analysis research, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/general/seido/kousei/i-kenkyu/genome/0504sisin.html,” and “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hokabunya/kenkyujigyou/i-kenkyu/index.html#HID1_mid1.” Therefore, it is not subject to ethical examination. The study was an observational study without any research subjects. No consent to participate was required due to the retrospective nature of this study.

No administrative permissions or licenses were required to access the raw data from the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database because all results were obtained from data openly available online from the PMDA website. All data from the JADER database were fully anonymized by the regulatory authority before we accessed them.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Ryogo Umetsu is an employee of Micron Inc. The rest of authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Histograms and the corresponding Weibull shape parameters of AKIs associated with 14 anti-infective categories for which the number of cases was more than 100 and the lower limit of the 95% CI exceeded 1 in Table 3. Three different time-to-onset periods of reported cases per anti-infective category were the limit to calculate the Weibull shape parameter. Six anti-infective categories [fourth-generation cephalosporins (po), carbapenems (po), other aminoglycosides (po), polymyxins (po), antibiotics (po), other antimycotics for systemic use (po)] did not meet this limit.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Suspected drugs classified by the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system and the Defined Daily Dose (ATC/DDD).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakao, S., Hasegawa, S., Umetsu, R. et al. Pharmacovigilance study of anti-infective-related acute kidney injury using the Japanese adverse drug event report database. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 22, 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-021-00513-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-021-00513-x