Abstract

Background

Genetic variation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) gene polymorphism has been suggested to modulate coronary heart diseases (CHD), yet the underlying mechanisms are not well understood.

Methods

We investigated the association of MMP9 rs3918242 single nucleotide polymorphism with inflammation and lipid-lowering efficacy after simvastatin treatment in Chinese patients with CHD. Fasting serum lipid profile and plasma inflammatory mediators were determined at baseline in 264 patients with CHD and 186 healthy control subjects, and after HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin treatment (20 mg/day) for 12 weeks in CHD subjects.

Results

We found that plasma MMP-9, TNF-α and IL-10 levels were significantly elevated in patients with CHD compared to control subjects before treatment. The plasma MMP9 in CHD patients carrying rs3918242 CC, CT and TT genotypes were comparable. Interestingly, CHD patients carrying TT genotype had significantly higher level of triglyceride (TG) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) than those carrying CC genotype (P <0.05). Simvastatin treatment significantly reduced LDL-C, TG and plasma inflammatory mediator levels in CHD patients. The reduction of LDL-C upon simvastatin therapy was significantly greater in patients carrying TT genotype than those carrying CC genotype (P <0.05).

Conclusions

MMP9 rs3918242 TT genotype is associated with elevated serum TG and LDL-C, and enhanced LDL-C-lowering response upon simvastatin treatment in Chinese patients with CHD.

Clinical trial registration

This study was retrospectively registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Registration number: ChiCTR-ROC-17010971) on March 23rd 2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases collectively capable of degrading essentially all components of extracellular matrix [1]. One of the MMP family member, MMP9, has been shown to involve in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases [2, 3]. Furthermore, MMP9 SNP rs3918242 and circulating MMP9 level are associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) progression and MI, arterial stiffness and cardiovascular disease mortality in patients with CHD [4–7], while the mechanisms are not completely understood.

CHD is characterized by elevated circulating pro-inflammatory mediators including TNF-a and IL-6, and reduced anti-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-10 [8]. The imbalance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators contributed to CHD progression [9]. Several lines of evidence suggest a potential link of plasma MMP9 activity to plasma TNF-a level, and a negative association with plasma IL-10 level in chronic inflammatory conditions [10]. However, whether MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism is associated with altered plasma MMP9 level and plasma inflammatory mediators in the Chinese patients with CHD has not been characterized [11].

The clinical beneficial effects of statin therapy in reducing the risk of coronary events and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease are believed to be the result of its cholesterol-lowering and anti-inflammatory actions [12, 13]. Studies have shown that statin therapy reduces circulating MMP9 level in CHD patients and decreases MMP9 secretion in experimental conditions [14, 15]. It is still unclear if the decreased MMP9 level or activity upon statin therapy might merely correlate with or modulate its lipid-lowering efficacy in patients with CHD.

In this study, we examined the association of MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism on MMP9 level, lipid profiles and inflammatory mediators in the blood in response to simvastatin therapy in Chinese patients with CHD.

Methods

Research participants

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University. We recruited 264 coronary heart diseases patients (112 females, 152 males; 55–78 years old), who underwent coronary angiography in the fourth clinical hospital of Harbin medical university. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants with a full explanation of the study. Coronary arteriograms were interpreted by two or more independent, experienced cardiologists in a blinded manner. CHD was defined as over 50% stenosis in at least one major vessel. The inclusion criteria were: (1) diagnosed of CHD (2) strictly abstained from smoking, alcohol and caffeine during treatment. The exclusion criteria were (1) subjects who had taken or were currently taking HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors; (2) individuals with liver or kidney failure or subject to liver or kidney transplantation, diabetes mellitus, dropsical nephritis and diagnosed myocardial infarction; (3) subjects who had taken any other lipid-lowering medication within 2 months before the study were also excluded. The control population consisted of 186 healthy subjects (90 females, 96 males; 52–79 years old) who had routine health check at medical examination center.

Blood collection and biochemical analysis

All subjects were asked to take low-fat diet and administered simvastatin 20 mg per oral ever day at bedtime. Fasting serum lipids were determined before and after 12 weeks of statin treatment. Total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C) in plasma were measured by enzymatic methods using an auto-analyzer. Plasma glucose levels were measured using an automated glucose oxidase method described before. Serum MMP9 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the monoclonal antibody against MMP9 [16]. The plasma TNF-α level was quantified using a sandwich ELISA kit (rat TNF-α/TNFSF1A, Duoset, R&D Systems, Abington, UK) and IL-10 level was assessed using the ChemiArray Rat Cytokine Antibody Array I kit (Chemicon-Millipore).

Genotyping of human MMP-9 gene 1562C > T polymorphism

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The MMP9 gene rs3918242 polymorphism was determined by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) based protocol [13]. Briefly, a 435 bp region in the promoter of MMP-9 gene, −1809 to −1374 upstream of MMP-9 transcription start site (TSS), was amplified. Forward primer 5′-GCCTGGCACATAGTAGGCCC-3′, reverse primer 5′-CTTCCTAGCCAGCCGGCATC-3′. The amplification reaction mix included 20 ng genomic DNA, dNTP (0.8uM), forward and reverse primer (0.5uM each), Prozyme DNA polymerase (0.5 unit) in the PCR buffer. PCR reaction was performed according to manufacturer’s manual. Aliquots of the PCR product were then fragmented using SphI restriction enzyme, and the the digestion products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 13.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Allele frequencies were estimated by gene counting. ANOVA was applied to compare average values of biochemical parameters between genotypes; Chi-square test was used to compare genotype and gene frequencies between the groups. Comparison between control and CAD subjects were performed using student’s T test. Comparison of parameters before and after statin treatment were conducted using paired student’s T test. All data were presented as the mean ± SD. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Genotype and allele frequencies of MMP9-1562C/T in CHD patients and controls

We recruited 264 CHD patients who underwent coronary angiography in the fourth clinical hospital of Harbin Medical University during 2013–2014 (112 females, 152 males; age range 55–78 years). 186 control subjects were age and sex-matched healthy subjects who had a routine health check at the medical examination center of Harbin Medical University (90 females, 96 males; age range 52–79 years). Genotyping for MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism were performed in all the CHD subjects using the genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes (Fig. 1). The genotype distributions in patients with CHD and controls were present in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. As shown in Table 1, the genotype and allele frequencies of MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism were similar between the control subjects and patients with CHD (P > 0.05).

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients with CHD and control subjects

Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the CHD patients and control subjects. All patients had at least one risk factor for coronary artery disease, including smoking, alcohol abuse and lack of exercise. Coronary heart disease was strongly associated with smoking (CHD patients compared with controls: P <0.05). At baseline, patients with CHD had significantly higher levels of serum TG, TC, LDL-C, VLDL-C, MMP-9, TNF-α and IL-10 and lower level of HDL-C than control subjects (P <0.05).

Effects of simvastatin on plasma lipids and MMP-9,TNF-α and IL-10

After 12-weeks simvastatin treatment in combination with the low-fat diet, serum TG, TC, LDL-C and VLDL-C levels were significantly decreased and the HDL-C level was increased in patients with CHD. Furthermore, plasma MMP9, TNF-α and IL-10 were also markedly reduced in CHD patients (Table 3).

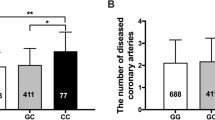

Influence of the MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism on plasma levels of lipid and inflammatory mediators

Given that MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism has been suggested to regulate MMP expression [17, 18], we first determined the effect of the rs3918242 polymorphism on plasma MMP9 level. The average level of MMP9 in subjects with TT genotype was similar to subjects carrying CT and CC genotypes in this cohort (Table 4 and Fig. 2A). Serum TG and LDL-C levels of patients carrying TT genotype were significantly increased compared to patients carrying CC genotype (P <0.05), while HDL-C, VLDL-C, TC, TNF-α and IL-10 levels were comparable in three groups before statin treatment (Table 4 and Fig. 2B). Statin treatment significantly elevated plasma HDL-C, and reduced the levels of LDL-C, TG, TC and VLDL-C in three groups of CHD patients. Notably, the reduction of LDL-C in patients carrying TT genotype was more robust than the LDL-C reduction in patients carrying CC genotype after statin treatment (34.53% vs. 24.23%, P <0.05). Interestingly, the reduction of TG, TC, VLDL-C, MMP-9, TNF-α and IL-10 were similar in three groups of patients (Table 4). These findings revealed a novel link of MMP9 rs3918242 TT genotype to the increased serum LDL-C and TG at baseline, and more robust LDL-C-lowering response to statin treatment compared to CHD patients carrying CC genotype.

Concentrations of MMP9 and LDL-C in the blood, and percentage of concentration reduction in CHD patients and control subjects before and after simvastatin treatment. a Plasma MMP9 concentration in CHD patients before and after simvastatin treatment (the left graph), and the percentage of plasma MMP9 concentration reduction in CHD. b Serum concentration of LDL-C in CHD patients before and after simvastatin treatment (the left graph), and the percentage of serum LDL-C concentration reduction in CHD. Error Bars represent 95% confident interval (95% CI). n = 188 subjects with CC, 69 subjects with CT and 7 subjects with TT genotype. *P <0.05, by One-Way ANOVA followed with Bonferroni pairwise test

Discussion

In this study, we showed that CAD patient carrying MMP9 rs3918242 TT genotype had significantly increased plasma TG and LDL-C levels than patients carrying CC genotype, and their LDL-C lowering response to simvastatin treatment were more robust than patients with CC genotype. These findings revealed a novel link of the MMP9 SNP polymorphism to LDL-C lowering response to simvastatin treatment in CHD patients.

Studies have consistently supported the correlation of MMP-9 rs3918242 polymorphism correlated with increased susceptibility to a variety of diseases [19–21], including coronary artery diseases [22]. The previous study also revealed that MMP-9 rs3918242 polymorphism was associated with the susceptibility to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the Uygur population of China [23]. In the present study, we examined the effects of the MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism on plasma MMP-9 level before and after simvastatin treatment in Chinese CHD patients. We found that plasma MMP-9 levels were elevated in patients with CHD compared to control subjects, and simvastatin treatment reduced plasma MMP-9 in CHD patients. However, MMP9 levels in patients with different MMP9 rs3918242 polymorphism were comparable before and after simvastatin treatment. Early studies revealed that the MMP9 rs3918242 CC genotype was responsible for lower activity of MMP-9 and genotypes with the T allele (CT, TT) were responsible for higher activity [18, 24]. The T-alleles’ effect on circulating MMP-9 levels exclusively in obese and lack of such influence in lean people has further been reported [25, 26]. Because the recruited CHD patients in the current cohort were not obese (average BMI = 24.73), our report further confirmed that the T-allele’s effect on circulating MMP9 level were lacking in non-obese people.

Studies in humans and animal models have provided evidences for a significant involvement of in atherosclerotic plaque progression, through degrading extracellular matrix, destabilizing advanced atherosclerotic plaques and facilitating vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation [3, 27, 28]. Emerging evidences suggest that MMP-9 is also involved in lipoprotein modification during progression of atherosclerotic lesions [29]. Higher levels of MMP-9 have been consistently observed to correlate with increasing total cholesterol or LDL-C levels in humans and animal models [30, 31], suggesting a potential link of MMP-9 rs3918242 polymorphism to serum LDL-C. In this study, we showed that CHD patients with MMP-9 rs3918242 genotype had elevated serum TG and LDL-C levels before simvastatin treatment. More important, we showed that patients with TT genotype had significantly more robust LDL-C lowering effect in response to simvastatin treatment than those with CC genotype. Although the association of LDL-C level with MMP9 polymorphism has been reported in other studies [32, 33], this study is the first to demonstrate that MMP9 polymorphism is associated with LDL-C lowering efficacy after simvastatin treatment, and thus provides new evidences on the link of genetic variations to the efficacy of lipid lowering medications.

This study has several limitations. (1) All the CHD patients were given simvastatin in combination with low-fat diet intervention. Therefore, the LDL-C lowering effect could possibly be biased by the diet intervention. Future studies without diet intervention would be helpful to address this problem. (2) The current CHD cohort contains 41.23% current smokers. It was reported that MMP9 level in the blood was significantly higher in current smokers compared to never and former smokers [34]. Hence, it would be important to analyze the serum MMP9 level and LDL-C lipid lowering effect with further stratification for smoking. (3) Patients in this cohort were uniformly treated with the medium dose of simvastatin (20 mg/day) for 12 weeks, and their serums LDL-C was significantly reduced to the level comparable to the control subjects. In this context, we found that patients carrying MMP9 rs3918242 TT genotype had more robust LDL-C-lowering response to statin treatment compared to patients carrying CC genotype. It would be interesting to examine whether the association of genetic variation of MMP9 rs3918242 with simvastatin’s LDL-C lowering response was dose-dependent. We expected improved LDL-C-lowering response of MMP9 rs3918242 T-allele to simvastatin even at lower dose.

Conclusions

In conclusion, MMP9 rs3918242 T-allele is associated with elevated plasma TG, increased LDL-C and improved LDL-C-lowering response to simvastatin treatment in Chinese patients with CHD. Further studies with larger sample sizes are required to confirm these findings and to explore the underlying mechanisms.

Abbreviations

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HMG-CoA:

-

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MMP:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

References

Chadzinska M, Baginski P, Kolaczkowska E, Savelkoul HF, Kemenade BM. Expression profiles of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in teleost fish provide evidence for its active role in initiation and resolution of inflammation. Immunology. 2008;125(4):601–10.

Wang X, Shi LZ. Association of matrix metalloproteinase-9 C1562T polymorphism and coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2014;15(3):256–63.

Luttun A, Lutgens E, Manderveld A, Maris K, Collen D, Carmeliet P, et al. Loss of matrix metalloproteinase-9 or matrix metalloproteinase-12 protects apolipoprotein E-deficient mice against atherosclerotic media destruction but differentially affects plaque growth. Circulation. 2004;109(11):1408–14.

Blankenberg S, Rupprecht HJ, Poirier O, Bickel C, Smieja M, Hafner G, et al. Plasma concentrations and genetic variation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 and prognosis of patients with cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107(12):1579–85.

Koh YS, Chang K, Kim PJ, Seung KB, Baek SH, Shin WS, et al. A close relationship between functional polymorphism in the promoter region of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127(3):430–2.

Medley TL, Cole TJ, Dart AM, Gatzka CD, Kingwell BA. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 genotype influences large artery stiffness through effects on aortic gene and protein expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(8):1479–84.

Wu HD, Bai X, Chen DM, Cao HY, Qin L. Association of genetic polymorphisms in matrix metalloproteinase-9 and coronary artery disease in the Chinese Han population: a case-control study. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(9):707–12.

Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1685–95.

Koltsova EK, Hedrick CC, Ley K. Myeloid cells in atherosclerosis: a delicate balance of anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory mechanisms. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24(5):371–80.

Gurkan A, Emingil G, Saygan BH, Atilla G, Cinarcik S, Kose T, et al. Gene polymorphisms of matrix metalloproteinase-2, -9 and -12 in periodontal health and severe chronic periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53(4):337–45.

Tian YC, Chen YC, Chang CT, Hung CC, Wu MS, Phillips A, et al. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 enhance HK-2 cell migration through a synergistic increase of matrix metalloproteinase and sustained activation of ERK signaling pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(11):2367–77.

Wenger NK, Shaw LJ, Vaccarino V. Coronary heart disease in women: update 2008. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(1):37–51.

Stancu C, Sima A. Statins: mechanism of action and effects. J Cell Mol Med. 2001;5(4):378–87.

Izidoro-Toledo TC, Guimaraes DA, Belo VA, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. Effects of statins on matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors in human endothelial cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;383(6):547–54.

Turner NA, O'Regan DJ, Ball SG, Porter KE. Simvastatin inhibits MMP-9 secretion from human saphenous vein smooth muscle cells by inhibiting the RhoA/ROCK pathway and reducing MMP-9 mRNA levels. FASEB J. 2005;19(7):804–6.

Fujimoto N, Hosokawa N, Iwata K, Shinya T, Okada Y, Hayakawa T. A one-step sandwich enzyme immunoassay for inactive precursor and complexed forms of human matrix metalloproteinase 9 (92 kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase, gelatinase B) using monoclonal antibodies. Clin Chim Acta. 1994;231(1):79–88.

Tu HF, Wu CH, Kao SY, Liu CJ, Liu TY, Lui MT. Functional -1562 C-to-T polymorphism in matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) promoter is associated with the risk for oral squamous cell carcinoma in younger male areca users. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(7):409–14.

Zhang B, Ye S, Herrmann SM, Eriksson P, de Maat M, Evans A, et al. Functional polymorphism in the regulatory region of gelatinase B gene in relation to severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1999;99(14):1788–94.

Vokurka J, Klapusova L, Pantuckova P, Kukletova M, Kukla L, Holla LI. The association of MMP-9 and IL-18 gene promoter polymorphisms with gingivitis in adolescents. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54(2):172–8.

Vairaktaris E, Vassiliou S, Nkenke E, Serefoglou Z, Derka S, Tsigris C, et al. A metalloproteinase-9 polymorphism which affects its expression is associated with increased risk for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(4):450–5.

Zivkovic M, Djuric T, Dincic E, Raicevic R, Alavantic D, Stankovic A. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 -1562 C/T gene polymorphism in Serbian patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;189(1-2):147–50.

Opstad TB, Arnesen H, Pettersen AA, Seljeflot I. The MMP-9 -1562 C/T polymorphism in the presence of metabolic syndrome increases the risk of clinical events in patients with coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e106816.

Wang L, Ma YT, Xie X, Yang YN, Fu ZY, Liu F, et al. Association of MMP-9 gene polymorphisms with acute coronary syndrome in the Uygur population of China. World J Emerg Med. 2011;2(2):104–10.

Morgan AR, Zhang B, Tapper W, Collins A, Ye S. Haplotypic analysis of the MMP-9 gene in relation to coronary artery disease. J Mol Med (Berl). 2003;81(5):321–6.

Demacq C, Vasconcellos VB, Marcaccini AM, Gerlach RF, Silva Jr WA, Tanus-Santos JE. Functional polymorphisms in the promoter of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) gene are not linked with significant plasma MMP-9 variations in healthy subjects. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(1):57–63.

Belo VA, Souza-Costa DC, Luizon MR, Lanna CM, Carneiro PC, Izidoro-Toledo TC, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 genetic variations affect MMP-9 levels in obese children. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36(1):69–75.

Dwivedi A, Slater SC, George SJ. MMP-9 and -12 cause N-cadherin shedding and thereby beta-catenin signalling and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81(1):178–86.

Tan C, Liu Y, Li W, Deng F, Liu X, Wang X, et al. Associations of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 concentrations with carotid atherosclerosis, based on measurements of plaque and intima-media thickness. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232(1):199–203.

Torzewski M, Suriyaphol P, Paprotka K, Spath L, Ochsenhirt V, Schmitt A, et al. Enzymatic modification of low-density lipoprotein in the arterial wall: a new role for plasmin and matrix metalloproteinases in atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(11):2130–6.

Sundstrom J, Vasan RS. Circulating biomarkers of extracellular matrix remodeling and risk of atherosclerotic events. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006;17(1):45–53.

Saedi M, Vaisi-Raygani A, Khaghani S, Shariftabrizi A, Rezaie M, Pasalar P, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 functional promoter polymorphism 1562C > T increased risk of early-onset coronary artery disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(1):555–62.

Sim DW, Maran AG, Harris D. Metastatic salivary pleomorphic adenoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104(1):45–7.

Mazzotti DR, Singulane CC, Ota VK, Rodrigues TP, Furuya TK, de Souza FJ, et al. Association of APOE, GCPII and MMP9 polymorphisms with common diseases and lipid levels in an older adult/elderly cohort. Gene. 2014;535(2):370–5.

Snitker S, Xie K, Ryan KA, Yu D, Shuldiner AR, Mitchell BD, et al. Correlation of circulating MMP-9 with white blood cell count in humans: effect of smoking. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66277.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This study is supported by the internal research funding provided by Department of Cardiology, The Fourth Hospital Affiliated to Harbin Medical University.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the conclusions of this study are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

YX conducted all the experiments and drafted the manuscript; YW participated in SNP genotyping; JZ participated in the design of experiment and performed statistical analysis; LQ and TZ conducted the measurement of MMP9 and IL-10; XL conceived of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants after a full explanation of the study. This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s information in any form.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Wang, Y., Zhi, J. et al. Impact of matrix metalloproteinase 9 rs3918242 genetic variant on lipid-lowering efficacy of simvastatin therapy in Chinese patients with coronary heart disease. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 18, 28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-017-0132-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-017-0132-y