Abstract

Background

In vitro studies have demonstrated that lithium has antiviral properties, but evidence from human studies is scarce. Lithium is used as a mood stabilizer to treat patients with bipolar disorder. Here, the aim was to investigate the association between lithium use and the risk of respiratory infections in patients with bipolar disorder. To rule out the possibility that a potential association could be due to lithium’s effect on psychiatric symptoms, we also studied the effect of valproate, which is an alternative to lithium used to prevent mood episodes in bipolar disorder.

Method

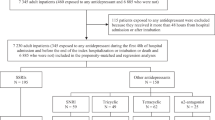

We followed 51,509 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the Swedish Patient register 2005–2013. We applied a within-individual design using stratified Cox regression to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) of respiratory infections during treated periods compared with untreated periods.

Results

During follow-up, 5,760 respiratory infections were documented in the Swedish Patient Register. The incidence rate was 28% lower during lithium treatment (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61–0.86) and 35% higher during valproate treatment (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.06–1.73) compared with periods off treatment.

Conclusions

This study provides real-world evidence that lithium is associated with decreased risk for respiratory infections and suggests that the repurposing potential of lithium for potential antiviral or antibacterial effects is worthy of investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outbreak of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19 (Corona virus Disease-2019) respiratory disease, has prompted a search for approved drugs with antiviral properties that might be repurposed to treat covid-19, or shed light on biological mechanisms that might be targeted for antiviral purposes.

Lithium has been suggested to have antiviral properties since the 1970-1980s (Rybakowski 2000; van den Ameele et al. 2016; Murru et al. 2020). In vitro studies have shown that lithium inhibit replication of several viruses (Skinner et al. 1980; Ren et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2017; Qian et al. 2018). Interestingly, in vitro studies have also shown lithium to effectively suppress infection with Porcine deltacoronavirus (Zhai et al. 2019) and other viruses that belong to the Coronaviridae family (Murru et al. 2020), albeit usually in concentrations that would be toxic in humans (Nowak and Walkowiak 2020).

As pointed out in a recent review (Murru et al. 2020), however, there is scarce evidence to support that lithium therapy affects the risk of infections or infection severity in humans. Small studies in the 1990s suggested reduced rates of herpes virus infections with lithium (Amsterdam et al. 1990a, b; Amsterdam et al. 1990a, b; Amsterdam et al. 1996). A retrospective review of 236 patients with affective disorders found that lithium treated patients showed a small reduction of flu-like illness during lithium therapy (Amsterdam et al. 1998).

Lithium is the mainstay prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder (Joas et al. 2017). Here, we leveraged a Swedish cohort of more than 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder followed over eight years to investigate if lithium treatment is associated with risk of respiratory infections. We employed a within-individual design to circumvent the problem of confounding by indication. With each person serving as his or her own matched control, the within-individual design controls for fixed confounders (e.g., baseline severity of the illness, genetic predisposition, childhood environment) (Lichtenstein et al. 2012). To rule out the possibility that a potential association between lithium and respiratory infection rate is secondary to the effect on psychiatric symptoms, we also calculated the association between valproate medication and respiratory infections. Valproate is a commonly used alternative to lithium to prevent mood episodes in bipolar disorder (Cipriani et al. 2013), recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) when lithium is not suitable (Kendall et al. 2014).

Methods

Subjects

We linked several longitudinal Swedish population-based registers through unique personal identification numbers (Ludvigsson et al. 2009): the Total Population Register, the Migration Register, the Cause of Death Register, the Patient Register (captures information on inpatient care since 1973 and outpatient visits to specialists care since 2001), and the Prescribed Drug Register (Wettermark et al. 2007). We identified 51,509 individuals with bipolar disorder followed from 1 October 2005, or age 15, or date of bipolar disorder diagnosis (if later than 1 October 2005) until emigration, death, or 31 December 2013, whichever occurred first. This date was chosen because the register linkage was conducted during 2015 with access to data up to December 2013. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet.

Bipolar disorder cases

To identify cases with bipolar disorder in the Patient Register, we applied a validated algorithm (Sellgren et al. 2011) that has been used in several previous Swedish register-based studies on bipolar disorder (Viktorin et al. 2014, 2017; Song et al. 2017). This algorithm includes bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective disorder bipolar type.

Medications

The main exposure was defined as dispensed prescriptions of lithium sulphate (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification code: N05AN01) or sodium valproate/valproic acid (N03AG01) as documented in the prescribed drug register. In Sweden, long-term prescribed medications are dispensed for three-month periods. Similar to previous studies (Song et al. 2017), we therefore defined a medication period as a sequence of at least two prescriptions, with no more than three months (92 days) between any two consecutive prescriptions. Thus, for both lithium and valproate, individuals were defined as on medication during the time interval between two dispensed prescriptions, unless the dispensed prescriptions occurred more than three months apart. To determine whether an individual was on/off medication initially, the start of follow-up was set to 1 October 2005 because the prescribed drug register started 1 July 2005.

Outcomes

In Sweden, uncomplicated respiratory infections are commonly treated in primary health care and therefore not recorded in the Patient register. Viral infections complicated by bacterial superinfection may, however, warrant specialist care or warrant hospital in-patient treatment. Hence, patients with a viral respiratory infection are likely to be diagnosed with bacterial pneumonia. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 27 studies, including a total of 3,215 patients, found that bacterial coinfection was very common (up to 65%) among patients hospitalized for influenza (Klein et al. 2016). The authors conclude that bacterial coinfection should always be suspected in all patients with influenza. We therefore defined outcome as being diagnosed with either viral or bacterial respiratory infections. Specifically, the outcomes were defined as influenza or other viral pneumonia (ICD-10 codes: J09, J10, J11.0, J11.1, J12), bacterial pneumonia (ICD-10 codes: J13, J14, J15, J16), pneumonia in other diseases (ICD-10 code: J17.1), pneumonia due to unspecified organisms (ICD-10 code: J18), acute bronchitis (ICD-10 code: J20), acute bronchiolitis (ICD-10 code: J21), and unspecified acute lower respiratory infection (ICD-10 code: J22). In an additional posthoc analysis, we limited outcomes to respiratory infection diagnoses specifically caused by viruses (ICD-10 codes: J09, J10, J11.0, J11.1, J12, J17.1, J20.3-7, and J21.0-1). Dates and diagnoses were retrieved from the National Patient Register that covers in-patient care and doctor visits from private and public caregivers, with the exception of primary care which is not covered.

Statistical analyses

We performed within-individual analyses using stratified Cox regression. By comparing treated and untreated periods within the same individual, this approach automatically controls for all time-stationary confounders and thus reduces the likelihood of confounding by indication. More details about this method are given in a review (Allison 2009).

We split the follow-up time into consecutive periods. A new period started after a medication switch (i.e., from off medication to on medication or vice versa, for either lithium or valproate) or a respiratory infection diagnosis. For the latter, we restarted the following period at baseline (i.e., to set the underlying time scale as the time since last diagnosis). Lithium and valproate treatment status were defined as time-varying dichotomous exposures. Age band (15–51, 51–64, 64–75, 75–100 years, grouped by the quartiles of the baseline age distribution among those who had an event during the follow-up) was adjusted for as a time-varying categorical covariate. We estimated the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for respiratory infections during periods with treatment as compared with periods off treatment. This method have previously been described in detail (Lichtenstein et al. 2012; Chang et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014; Molero et al. 2015).

All analyses were performed with Stata 16.0 (StataCorp. 2013).

Results

Among the 51,509 patients with bipolar disorder, a total of 5760 respiratory infections were diagnosed in 3,389 individuals (6.6%) during 217,214 person-years of follow-up (Table 1). Lithium treatment was more prevalent (41.0%) than valproate treatment (15.9%). About 50% patients were not exposed to lithium or valproate during the study period. Additional file 1: Table S1 outlines the characteristics of patients treated with lithium, valproate, or both during the study period.

After excluding individuals without respiratory infections and varying covariates (i.e., treatment status and age band) during follow-up, 3285 individuals were eligible for the within-individual analysis. These patients experienced a total of 5656 respiratory infections.

The rate of respiratory infection diagnoses was 27% lower during periods on lithium treatment compared with periods off lithium (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61–0.86). By contrast, the rate of respiratory infections was higher during periods with valproate treatment (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.06–1.73).

When we in a post hoc analysis limited the diagnoses to viral respiratory infections, the number of events dropped by 97% to 199. In this analysis, neither lithium (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.35–3.22) nor valproate (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.24–4.37) was significantly associated with the risk of viral respiratory infections.

Discussion

In a large sample of patients with bipolar disorder, we found that rates of respiratory infection diagnosed at hospitals or specialist outpatient care were significantly lower while on lithium medication than during periods off lithium. By contrast, the rate of respiratory infections was increased during medication with the alternative mood stabilizer valproate. Given that we used a within-individual design—and that lithium and valproate both effectively prevent mood episodes in bipolar disorder—the difference is likely to be caused by effects of the medication used.

Overall, the proportion of respiratory infections was higher in patients treated with lithium (7.3%) and valproate (8.6%) than in patients who were treated with any of these drugs (5.7%). However, this difference is likely to be confounded by indication, which is why a between group comparison does not provide information on whether lithium or valproate influence the risk of respiratory infections. For example, cases treated with lithium or valproate are more likely to have a more severe psychiatric disorder, to smoke, or have other unknown risk factors than cases never treated with any of these drugs. Moreover, cases that had used lithium or valproate were older and were more likely to be male than those who had never used lithium or valproate. The within-individual model that we used compares the risk of respiratory infections during periods with lithium (or valproate) medication with the risk during periods without lithium (or valproate) medication within each individual. The model thereby corrects for potential group differences such as sex, genetical make up, severity of the psychiatric disorder et cetera.

Bacterial coinfections or superinfections is a common complication of viral respiratory infections, especially in hospitalized patients (Klein et al. 2016). In the present study, it was not possible to distinguish between viral and bacterial respiratory infections because the results are compatible with effects on both viral and bacterial infections. The observed association of lithium treatment and low risk of respiratory infections therefore needs to be addressed in further investigations using broad diagnostic panels for viral as well as bacterial pathogens. The previously reported antiviral properties of lithium might, however, explain our results since an antiviral mechanism may also protect against bacterial complications.

Limited testing for viral pathogens in clinical routine care may explain the dramatic decrease of number of events (97%) when we limited the analysis to viral respiratory only infections in a post hoc analysis. This drop in sample size radically impaired statistical power and the post hoc analysis did not yield any significant results.

Although the antiviral effect of lithium remains speculative in vivo, our findings are in line with a small previous study (N = 236) that found a reduction of flu-like illness during lithium therapy.(Amsterdam et al. 1998) Although lithium is believed to act across several biological pathways and the exact mechanism of actions remains obscure (Alda 2015), it is known to inhibit glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) (Malhi and Outhred 2016). GSK3β has been suggested to be involved in inducing apoptosis and release of viral particles in dengue virus-2 infection (Cuartas-Lopez and Gallego-Gomez 2020), and GSK3β suppression is hence one potential mechanism underlying the antiviral effect of lithium (Sarhan et al. 2017). Lithium has also been found to induce leucocytosis (Carmen et al. 1993; Petrini and Azzara 2012), and attenuate anti-inflammatory effects during chronic use (reviewed by (van den Ameele et al. 2016)). Further, lithium may stimulate immunoglobulin production in B-lymphocytes, increase T-lymphocyte proliferation, and affect proinflammatory cytokine production (reviewed by (Maddu and Raghavendra 2015) and (van den Ameele et al. 2016)).

Valproate treatment, by contrast, increased the risk of respiratory infections. It is well known that valproate can cause reversible bone marrow suppression leading to leukopenia and neutropenia (Acharya and Bussel 2000). However, a meta-analysis of infectious diseases reported as adverse events during the double-blind phase of placebo-controlled randomized clinical studies failed to show a significant effect of valproate (Zaccara et al. 2017). It should be noted, however, that groups treated with lithium or valproate are likely to differ in several respects (Additional file 1: Table S1). Lithium is the recommended first treatment option in Sweden, why the group treated with valproate is likely to be less responsive to treatment and might also be a more severely ill group.

This is by far the largest study testing the hypothesis that lithium protects against respiratory infections. The within-individual design controls for time-invariant covariates that might confound the results, but the method is susceptible to confounding by factors associated with the exposure that change during the observation period. For example, periods on a mood stabilizer might be associated with better access to healthcare than periods off a mood stabilizer. Although we controlled for this by including valproate in our analyses, it cannot be excluded that time-varying confounding might differ between lithium and valproate. The main limitation is that we cannot discern if lithium protects against viral, bacterial, or other aetiologies. Another limitation is that we lack information on tobacco use and comorbidity, but this should not confound the results in a within-individual model. Limitations finally include the lack of information regarding adherence, but this would if anything be a conservative bias.

In conclusion, we provide real-world evidence that lithium treatment reduces the rate of respiratory infections. Taken together with ample previous literature on antiviral effects of lithium (Murru et al. 2020), the repurposing potential of lithium for antiviral effects is worth pursuing.

Availability of data and materials

The authors had full and ongoing access to the original data presented and analysed in this study. Due to Swedish legal restrictions, register data cannot be shared. However, the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

16 April 2021

OA Funding note added.

References

Acharya S, Bussel JB. Hematologic toxicity of sodium valproate. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:62–5.

Alda M. Lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder: pharmacology and pharmacogenetics. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:661–70.

Allison PD. Fixed effects regression models. CA: SAGE publications; 2009. p. 160.

Amsterdam JD, Maislin G, Potter L, Giuntoli R. Reduced rate of recurrent genital herpes infections with lithium carbonate. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990a;26:343–7.

Amsterdam JD, Maislin G, Rybakowski J. A possible antiviral action of lithium carbonate in herpes simplex virus infections. Biol Psychiatry. 1990b;27:447–53.

Amsterdam JD, Maislin G, Hooper MB. Suppression of herpes simplex virus infections with oral lithium carbonate–a possible antiviral activity. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:1070–5.

Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Rybakowski J. Rates of flu-like infection in patients with affective illness. J Affect Disord. 1998;47:177–82.

Carmen J, Okafor K, Ike E. The effects of lithium therapy on leukocytes: a 1-year follow-up study. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993;85:301–3.

Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, D’Onofrio BM, Sjolander A, Larsson H. Serious transport accidents in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effect of medication: a population-based study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:319–25.

Chen Q, Sjolander A, Runeson B, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Drug treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicidal behaviour: register based study. BMJ. 2014;348:g3769.

Chen Y, Kong D, Cai G, Jiang Z, Jiao Y, Shi Y, et al. Novel antiviral effect of lithium chloride on mammalian orthoreoviruses in vitro. Microb Pathog. 2016;93:152–7.

Cipriani A, Reid K, Young AH, Macritchie K, Geddes J. Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD003196.

Cuartas-Lopez AM, Gallego-Gomez JC. Glycogen synthase kinase 3ss participates in late stages of Dengue virus-2 infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2020;115:e190357.

Joas E, Karanti A, Song J, Goodwin GM, Lichtenstein P, Landen M. Pharmacological treatment and risk of psychiatric hospital admission in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:197–202.

Kendall T, Morriss R, Mayo-Wilson E, Marcus E, Guideline Development Group of the National Institute for H, Care E. Assessment and management of bipolar disorder: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g5673.

Klein EY, Monteforte B, Gupta A, Jiang W, May L, Hsieh YH, et al. The frequency of influenza and bacterial coinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2016;10:394–403.

Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist J, Sjolander A, Serlachius E, Fazel S, et al. Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2006–14.

Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:659–67.

Maddu N, Raghavendra PB. Review of lithium effects on immune cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2015;37:111–25.

Malhi GS, Outhred T. Therapeutic Mechanisms of Lithium in Bipolar Disorder: Recent Advances and Current Understanding. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:931–49.

Molero Y, Lichtenstein P, Zetterqvist J, Gumpert CH, Fazel S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and violent crime: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001875.

Murru A, Manchia M, Hajek T, Nielsen RE, Rybakowski JK, Sani G, et al. Lithium’s antiviral effects: a potential drug for CoViD-19 disease? Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020;8:21.

Nowak JK, Walkowiak J. Lithium and coronaviral infections. A scoping review. F1000Research. 2020;9:93.

Petrini M, Azzara A. Lithium in the treatment of neutropenia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19:52–7.

Qian K, Cheng X, Zhang D, Shao H, Yao Y, Nair V, et al. Antiviral effect of lithium chloride on replication of avian leukosis virus subgroup J in cell culture. Arch Virol. 2018;163:987–95.

Ren X, Meng F, Yin J, Li G, Li X, Wang C, et al. Action mechanisms of lithium chloride on cell infection by transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18669.

Rybakowski JK. Antiviral and immunomodulatory effect of lithium. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33:159–64.

Sarhan MA, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Mason AL, Tyrrell DL, Houghton M. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibitors prevent hepatitis C virus release/assembly through perturbation of lipid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2495.

Sellgren C, Landén M, Lichtenstein P, Hultman CM, Långström N. Validity of bipolar disorder hospital discharge diagnoses: file review and multiple register linkage in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:447–53.

Skinner GR, Hartley C, Buchan A, Harper L, Gallimore P. The effect of lithium chloride on the replication of herpes simplex virus. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1980;168:139–48.

Song J, Sjolander A, Joas E, Bergen SE, Runeson B, Larsson H, et al. Suicidal behavior during lithium and valproate treatment: a within-individual 8-year prospective study of 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:795–802.

StataCorp. Stata: release 13. Statistical software. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2013.

van den Ameele S, van Diermen L, Staels W, Coppens V, Dumont G, Sabbe B, et al. The effect of mood-stabilizing drugs on cytokine levels in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:364–73.

Viktorin A, Lichtenstein P, Thase ME, Larsson H, Lundholm C, Magnusson PK, et al. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:1067–73.

Viktorin A, Ryden E, Thase ME, Chang Z, Lundholm C, D’Onofrio BM, et al. The risk of treatment-emergent mania with methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:341–8.

Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:726–35.

Zaccara G, Giovannelli F, Giorgi FS, Franco V, Gasparini S, Tacconi FM. Do antiepileptic drugs increase the risk of infectious diseases? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:1873–9.

Zhai X, Wang S, Zhu M, He W, Pan Z, Su S. Antiviral effect of lithium chloride and diammonium glycyrrhizinate on porcine deltacoronavirus in vitro. Pathogens. 2019;8:144.

Zhao FR, Xie YL, Liu ZZ, Shao JJ, Li SF, Zhang YG, et al. Lithium chloride inhibits early stages of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) replication in vitro. J Med Virol. 2017;89:2041–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research was supported by grants from the Wenner-Gren foundation (SSv2019-0008), and the Swedish Medical Research Council (ML: 2018-02653).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML conception of the study, study design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript; HL and PL data acquisition, interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; JW interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; JS study design, analysis and interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet (2005/174 – 31/4; 2010/1258–32). The analyses were conducted on de-identified datasets and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are neither any financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, nor any other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of individuals with bipolar disorder by different treatment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Landén, M., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P. et al. Respiratory infections during lithium and valproate medication: a within-individual prospective study of 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord 9, 4 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-020-00208-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-020-00208-y